Abstract

Background

To understand how best to approach dementia care within primary care and its challenges, we examined the evidence related to diagnosing and managing dementia within primary care.

Methods

Databases searched include: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from inception to 11 May 2020. English-language systematic reviews, either quantitative or qualitative, were included if they described interventions involving the diagnosis, treatment and/or management of dementia within primary care/family medicine and outcome data was available. The risk of bias was assessed using AMSTAR 2. The review followed PRISMA guidelines and is registered with Open Science Framework.

Results

Twenty-one articles are included. The Mini-Cog and the MMSE were the most widely studied cognitive screening tools. The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) achieved high sensitivity (100 %, 95 % CI: 70-100 %) and specificity (82 %, 95 % CI: 72-90 %) within the shortest amount of time (3.16 to 5 min) within primary care. Five of six studies found that family physicians had an increased likelihood of suspecting dementia after attending an educational seminar. Case management improved behavioural symptoms, while decreasing hospitalization and emergency visits. The primary care educational intervention, Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs), was successful at increasing carer ability to manage problem behaviours and improving outcomes for caregivers.

Conclusions

There are clear tools to help identify cognitive impairment in primary care, but strategies for management require further research. The findings from this systematic review will inform family physicians on how to improve dementia diagnosis and management within their primary care practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-021-01461-5.

Keywords: Dementia, Primary care, Family physician, Systematic review, Diagnosis

Background

At any given time, 5–8 % of the general population aged 60 and over are living with dementia, and it is expected that 152 million people in the world will have dementia by 2050 [1]. The impact of dementia is far reaching, as it affects not only the person with dementia, but also their family carers, the healthcare system and society as a whole [1]. Dementia is often unrecognized, and there is an underuse of diagnostic assessment tools and a lack of attention to the issues faced by family caregivers [2]. Approximately 65 % of dementia cases are undiagnosed in primary care, which negatively impacts these patients by not implementing advanced care planning and management strategies before the dementia progresses [3]. The U.S Preventative Services Task Force recommends that clinicians assess cognitive functioning when a patient is suspected of cognitive impairment based on the physician’s observation or caregiver concerns [3]. Canadian consensus guidelines similarly do not recommend asymptomatic screening, but instead suggest use of validated screening tools if there is clinical concern for a cognitive disorder [4]. Common neuropsychological screening tools administered by family physicians (FPs) include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Clock Drawing Test (CDT) [3]. However, it is not clear that these are the best screening tools for use in primary care.

Time constraints are often an issue for family doctors as it relates to diagnosing and managing dementia. The time allocated for a typical office visit makes it challenging to perform a cognitive assessment [5]. FPs often feel uncertainty regarding the management of dementia after a diagnosis has been made [5]. This highlights the current need to better optimize dementia care within primary care. The objective of this systematic review of systematic reviews was to determine the most effective evidence-based strategies to diagnose and manage dementia within primary care. Specifically, we seek to understand what practices FPs can undertake to ensure accurate and timely testing and management.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines [6], and the protocol is registered in Open Science Framework [DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/E4AW5]. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1: Appendixes 1 and 2. A systematic review of systematic reviews was determined to be the past method to further summarize and tailor the current body of literature on this topic into a format that would address the existing evidence to practice gap.

Data Sources

The systematic literature search was developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian, with the final search being completed 11 May 2020. The following databases using the Ovid platform were searched without a restriction to publication date: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We searched the following clusters of search terms: Family Practice and Dementia. In each category, we used controlled vocabulary such as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) as well as keywords. Within each cluster, terms were combined with OR, and between the clusters with AND. We then used CADTH search terms for the systematic review study designs [7] (Additional file 1: Appendix 1). The reference list of a previous relevant systematic review of systematic reviews published in 2014 was also searched [8].

Study Selection

Systematic reviews were considered if they met the following inclusion criteria.

Population: Primary care or family practice settings seeing persons with dementia.

Intervention: The detection, diagnosis, treatment and/or management of dementia including models of care, pathways and/or protocols.

Comparators: Usual care, wait-list control or other interventions within the scope of the review.

Outcomes: The description of the detection, diagnosis, treatment or management strategies, along with measures of their acceptability, efficacy or effectiveness in the provision of care.

Study design: Systematic review, either quantitative or qualitative.

Articles were also selected for inclusion if they were English-language articles, included relevant descriptions of the interventions used, and outcome data was available.

Two reviewers (B.F and J.H.-L.) independently screened the titles and abstracts for possible inclusion. If either reviewer thought the citation was relevant or potentially relevant, the full-text article was then retrieved for further evaluation. All full-text articles were assessed independently for inclusion by B.F and J.H.-L. Any conflicts were resolved through discussion. One reviewer (B.F.) independently extracted the following information from the included full-text studies using a standardized data extraction form: authors, year of publication, country where the review was conducted, number of studies included, study designs included, databases searched, time frame of article search, inclusion and exclusion criteria, population (mean age, SD and dementia diagnosis), intervention, comparator, sample size, setting (if the intervention was cognitive screening, the method of administration), time of administration (if intervention was cognitive screening), cognitive outcome(s) measured, results (meta-analysis, Sn, Sp, accuracy), and other (Additional file 1: Appendix 2). One reviewer (B.F) categorized each study based on the primary category of intervention, which was verified by another reviewer (J.H-L).

Quality Assessment and Analysis

Two reviewers (B.F and J.H.-L.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the AMSTAR 2 Systematic Review Quality Appraisal Checklist 2020. Systematic reviews without a clear PICO were excluded. Best practices for quality assessment using AMSTAR 2 are to consider the impact of inadequate ratings for each category rather than generate an overall score. The AMSTAR 2 quality appraisal results for each of the included studies is available in Additional file 1: Appendix 3 [9]. A qualitative descriptive summary of the literature is presented.

Results

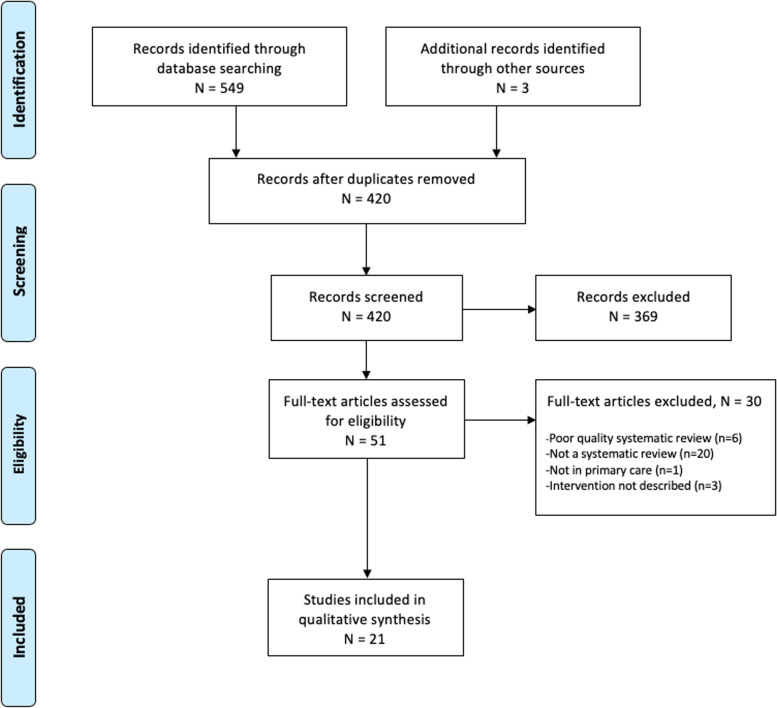

The initial search identified 417 unique citations for possible inclusion after duplicates were removed. After searching the reference list of a relevant previous systematic review of systematic reviews [8], three additional citations were collected and screened for eligibility. After screening the 420 citations, 369 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. From the 51 full-text articles screened, 30 articles were excluded. Reasons for exclusion include not being a systematic review (n = 20), describing a setting other than primary care (n = 1), failing to describe the intervention (n = 3), or a poor AMSTAR 2 rating (n = 6). This resulted in the inclusion of 21 articles (Fig. 1). The included studies were published between June 2003 and July 2019.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Screening tools

Nine [10–18] out of the 21 included systematic reviews describe screening tools for use in primary care (Table 1). Various screening tools, assessing cognitive impairment or dementia, were compared in terms of cognitive outcomes assessed, time to administer, and sensitivity and specificity. The MMSE was used as a reference standard in the majority of the included studies. The Mini-Cog (n = 5) and the MMSE (n = 7) were the most widely studied tools among the included reviews. The Mini-Cog takes approximately 3 min to administer, and sensitivity ranges from 76 to 100 % and specificity from 27 to 93 % [10, 12, 14, 17] depending upon the cut-off value used.

Table 1.

Screening tools and their comparators, cognitive outcomes, administration time, sensitivity and specific and conclusions from the literature included in this systematic review

| Reference, Country | Number of studies included in systematic review | Intervention(s) | Comparator | Cognitive outcome(s) measured | Time of administration (minutes) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity | Conclusions | Abbreviations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitchell et al, United Kingdom | 44 |

Multidomain screening tests (known as a battery detection method) in primary care which assess for multiple cognitive domains. Primary care case-finding † : ▪AMTS/MSQ, ▪MSQ ▪WIND-SET ▪PCL ▪AMTS ▪PCL Primary care screening ‡ : ▪ PCL ▪AMTS/MSQ ▪MSQ ▪SPMSQ ▪GPCOG |

MMSE | Dementia |

Primary care case-finding: ▪AMTS/MSQ = 4 ▪MSQ = 2 ▪WIND-SET = 1 ▪PCL = 11 ▪AMTS = 2 ▪PCL = 11 Primary care screening: ▪PCL = 11 ▪AMTS/MSQ = 4 ▪MSQ = 2 ▪SPMSQ = 2 ▪GPCOG = 5 Comparator: ▪MMSE = 9 with healthy individuals and 15 with patients with dementia. |

Battery detection methods: ▪84.0 (95% CI 74.2–91.8) |

Battery detection methods: ▪89.9 (95% CI 78.3–97.4) |

The optimal individual tools were the AMTS/MSQ and PCL. AMTS was superior to the MMSE for case finding however the MMSE was optimal for screening. |

AMTS/MSQ-Abbreviated Mental Test Score/Mental Status Questionnaire, (WIND-SET)-Specific Set of items from MMSE, PCL-Prueba cognitive de leganes, AMTS-Abbreviated mental test score, GPCOG-General practitioner’s assessment of cognition, MMSE-Mini-Mental State Examination † Case-finding is defined as any tool or questionnaire which identifies a condition with minimal false negatives, measured as the positive predicative value. ‡ Screening is the ability of a test to rule out a diagnosis with minimal false positives, reported as the negative predictive value. |

| Creavin et al, United Kingdom | 70 | ▪MMSE | A commonly accepted clinical (gold) reference standard. | Dementia | ▪MMSE=7 with a patient with dementia and 5 with a person with normal cognition |

Carnero-Pardo 2013: ▪Cut point of 17 = 70 (95% CI 59-80) ▪Cut point of 24 = 100 (95% CI 95-100) |

Carnero-Pardo 2013: ▪Cut point of 17 = 93 (95% CI 89, 96) ▪Cut point of 24 = 46 (95% CI 40-52) |

Carnero-Pardo 2013 reported there were some false negatives as the sensitivity fell from 1.00 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.00) to 0.70 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.80). The summary diagnostic accuracy could not be estimated due to insufficient data. | |

| Abd Razak et al, Malaysia | 30 |

▪MoCA-B; MoCA ▪SPMSQ ▪MEFO ▪ACE-III ▪AQT-CF ▪SLUMS ▪5 Object Test ▪BNB Semantic Fluency ▪SMCC compared to MMSE and CDT ▪CASI-S ▪RCS ▪CPS ▪Literacy Independent Cognitive Assessment ▪BIMS; BCAT ▪3MS ▪Mini-Cog; MIS; MF-2 ▪VT-VSM; VR-DOT ▪CCS ▪CAMCI ▪CADi; CADi-2 ▪DRA ▪p-AD8 ▪IQCODE |

Comparing the feasibility and validity between the various screening tools. | Mild cognitive impairment and dementia |

▪MoCA-B = 15-21; MoCA = 10-15 ▪SPMSQ = 10-15 ▪MEFO = 10-15 ▪ACE-III = 15 ▪AQT-CF = 3-5 ▪SLUMS = 7 ▪5 Object Test = <5 ▪BNB Semantic Fluency = 31 ▪MCC compared to MMSE and CDT = NR ▪CASI-S = NR ▪RCS = <3 ▪CPS = NR ▪Literacy Independent Cognitive Assessment = 20 ▪BIMS = 3; BCAT = 10-15 ▪3MS = 17 ▪Mini-Cog = 3; MIS = 4; MF-2 = <2 ▪VT-VSM = >12; VR-DOT = NR ▪CCS = 3 ▪CAMCI = 30 ▪CADi = 10; CADi-2 = 10-40 ▪DRA = NR ▪p-AD8 = NR ▪IQCODE = 10 |

For detecting dementia: ▪ACE-III at a cut-off point of <81, Sn = 100 For detecting MCI: ▪MoCA, Sn = 91-97 |

For detecting dementia: ▪ACE-III at a cut-off point of <81, Sp=96 For detecting MCI: ▪MoCA, Sp = 60-80 |

For detecting dementia: Screening tools less sensitive to ACE-III but with relatively high Sn/Sp values were: SLUMS, RCS, and BCAT. For detecting MCI: The MoCA was the most commonly used tool and had the highest Sn/Sp ranges. Less specific to the MoCA but among the most sensitive tools were the (VR-DOT) and IQCODE. Tools with the highest specificity but with lower sensitivity were: The 5 Objects Test, RCS, CPS, and (VT-VSM). |

NR-Not Reported, MCI-Mild Cognitive Impairment, (MoCA-B)-Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic, (MoCA)-Montreal Cognitive Assessment, SPMSQ-Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire, (MEFO)-Memory, fluency and orientation, (ACE-III)-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination III, (AQT-CF)-A Quick Test of Cognitive Speed, (SLUMS)- Saint Louis University Mental Status, (BNB)-Brief Neuropsychological Battery Semantic Fluency, (SMCC)-The Subjective Memory Complaint Clinical, (CASI-S)-Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument-Short, (RCS)-Rapid Cognitive Screen, (CPS)-Cognitive Performance Scale, (BIMS)-Brief Interview for Mental Status, (BCAT)-Brief Cognitive Assessment Tool, (3MS)-Modified Mini-Mental State Examination, (MIS)-Memory Impairment Screen, (MF-2)-Memory Function 2, (VT-VSM)-Virtual Reality technology: Virtual supermarket, (VR-DOT)-Virtual Reality Day-Out-Task, (CCS)-Computerized Cognitive Screening Tests, (CAMCI)-Computerized Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment, (CADi)-[Cognitive Assessment for Dementia, iPad version], (CADi-2)-[Revised Cognitive Assessment for Dementia, iPad version], (DRA)-Dementia Risk Assessment, (p-AD8)-Participant-rated, (IQCODE)- Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly individuals |

| Smith et al, United Kingdom | 33 |

▪Rural Older Adult Memory Evaluation ▪Mini-Cog ▪PRISM-PC ▪SAPH questionnaire ▪MMSE and clinical history/examination ▪7-minute screen ▪CIE and MMSE |

Not mentioned. | Dementia | Not mentioned. | Not mentioned. | Not mentioned. | There is insufficient evidence to support the adoption of these programmes into practice. Six positive and eight negative effects of primary care screening and early diagnosis of dementia were reported. | (PRISM-PC)-Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care, SAPH-Dementia Screening and Perceived Hames, CIE-The Canberra Interview for the Elderly |

| Brodaty et al, Australia | 83 |

Instruments Validated in General Practice, Community or Population Samples: ▪AMT ▪Cambridge Cognitive Examination ▪CDT ▪GPCOG ▪Mini-Cog ▪MIS ▪MMSE ▪Short and Sweet Screening Instrument ▪Short IQCODE |

MMSE | Dementia |

▪AMT = 3:16 ▪Camnridge Cognitive Examination = 20 ▪CDT = 2:16 ▪GPCOG = 4.5 ▪Mini-Cog = 2-4 ▪MIS = 4 ▪MMSE = 4 ▪Short and Sweet Screening Instrument = 10 ▪Short IQCODE = 30s |

Screening tests validated in general practice, community or population samples: ▪AMT-100 (95% CI 70-100) ▪Cambridge Cognitive Examination-88 (95% CI 64-99) ▪CDT-76 (95% CI 60-88) ▪GPCOG-85 (95% CI 76-92) ▪Mini-Cog-76 (95% CI 65-85) ▪MIS-80 (95% CI 66-90) ▪MMSE-69 (95% CI 66-73) ▪Short and Sweet Screening Instrument-94 (95% CI 88-96) ▪Short IQCODE-79 (95% CI 65-90) |

Screening tests validated in general practice, community or population samples: ▪AMT-82 (95% CI 72-90) ▪Cambridge Cognitive Examination-75 (95% CI 67-83) ▪CDT-81 (95% CI 77-84) ▪GPCOG-86 (95% CI 81-91) ▪Mini-Cog-89 (95% CI 87-91) ▪MIS-96 (95% CI 94-98) ▪MMSE-89 (95% CI 87-92) ▪Short and Sweet Screening Instrument-91 (95% CI 90-92) ▪Short IQCODE-82 (95% CI 79-85) |

Screening tests validated in general practice, community or population samples: AMT had a PPV=0.42 (95% CI), NPV=1.00 (95% CI), misclassification of 16%, had internal consistency and face validity. Mini-Cog had a PPV=0.34 (95% CI), NPV=0.98 (95% CI), 12% misclassification, no education bias or language/cultural bias, and had face validity*. The AMT, CDT, GPCOG, Short IQCODE, Mini-Cog, and MIS all had a NPV =< MMSE (0.92). The GPCOG, Mini-Cog and MIS had a misclassification rate =< MMSE (15%) and had a high sensitivity and specificity (>=80%) and were therefore chosen as the most suitable instruments for use in general practice. |

MAT-Mental Alternation Test. *- (Based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria requiring that instruments test memory and at least one other cognitive domain). CDT-Clock Drawing Test. GPCOG-General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition. |

| Seitz et al, Canada | 4 | The Mini-Cog performed in insolation or scored based on results on the CDT or three-word recall | Standard diagnostic criteria for the clinical diagnosis of dementia | Alzheimer's disease dementia and related dementias | Mini-Cog = 3-5 in routine practice |

Carnero-Pardo 2013 dementia prevalence was 34.5%: ▪100 (95% CI 93-100) Fuchs 2012 5.0% dementia prevalence: ▪100 (95% CI 84-100) Holsinger 2012 (highest quality study) 5.5% dementia prevalence: ▪76 (95% CI 53-92) McCarten 2012 90.3% dementia prevalence: ▪84 (95% CI 81-87) |

Carnero-Pardo 2013: ▪40 (95% CI 30-50) Fuchs 2012: ▪85 (95% CI 81-89) Holsinger 2012: ▪73 (95% CI 68-77) McCarten 2012: ▪27 (95% CI 16-41) |

Presently there is insufficient evidence to support the use of Mini-Cog in primary care. Studies mentioned are primary journal articles (cross-sectional studies). |

|

| Cullen et al, United Kingdom | 36 |

▪3MS ▪CASI ▪MMSE ▪SASSI ▪STMS ▪CAST ▪GPCOG ▪7MS ▪AMT ▪Mini-Cog ▪SIS ▪T&C ▪ACE-R ▪DemTect |

Gold standard diagnostic criteria (based on international diagnostic guidelines or clinical judgement following a full assessment battery). | Cognitive impairment or any type of dementia |

▪3MS = 10-15 ▪CASI = 15-20 ▪MMSE = 8-13 ▪SASSI = 10-15 ▪STMS = 5 ▪CAST = 15 ▪GPCOG = 5 ▪7MS = 7-15 ▪AMT = 5 ▪Mini-Cog = 3-4 ▪SIS = 5 ▪T&C = 1 ▪ACE-R = 16 ▪DemTect = 8-10 |

▪3MS = 83-94 ▪CASI = 91-95 ▪MMSE = 69-91 ▪SASSI = 94 ▪STMS = 86-95 ▪CAST = 88-95 ▪GPCOG = 85 ▪7MS = 91 ▪AMT = 73-100 ▪Mini-Cog = 76-99 ▪SIS = 81-89 ▪T&C = 63-95 ▪ACE-R = 84-94 ▪DemTect = 100 (Alzheimer's dementia) |

▪3MS = 85-90 ▪CASI = 37-97 ▪MMSE = 87-99 ▪SASSI = 81-91 ▪STMS = 88-94 ▪CAST = 88-100 ▪GPCOG = 86 ▪7MS = 94 ▪AMT = 71-100 ▪Mini-Cog = 89-93 ▪SIS = 88-91 ▪T&C = 54-96 ▪ACE-R = 89-100 ▪DemTect = 92 (Alzheimer's dementia) |

These tests were selected as brief assessment tools in the doctor's office due to their reported sensitivity and specificity values that were >85% for all dementia types together or for more than one particular subtype alone, and/or they covered at least three key domains. The 3MS and CASI are the only tests which cover all six key abilities (Attention/working memory, verbal recall, expressive language, verbal fluency, visual construction, reasoning/judgement). |

(ACE-R)-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination Revised, STMS-Short Test of Mental Status, CCSE-Cognitive Capacity Screening Examination, (R-CAMCOG)-Rotterdam Version of the Cambridge Cognitive Examination |

| Lischka et al, Canada | 12 |

▪MIS ▪IST, BVRT ▪CAMCI ▪ACE ▪ADAS-Cog ▪CAMCOG ▪MoCA ▪S-MMSE ▪IQCODE ▪STMS ▪MMSE ▪HDS-R ▪CCSE |

A full clinical examination as the reference standard. | Dementia, MCI, amnestic MCI, mild dementia, and questionable dementia. |

▪MIS, IST = 4 ▪IST, BVRT = 1 ▪CAMCI = 15 ▪ACE = 15 ▪ADAS-Cog = NR ▪CAMCOG = 20 ▪MoCA = 10-12 ▪S-MMSE = 10 ▪IQCODE = 10-20 ▪STMS = 5 ▪MMSE = 5-10 ▪HDS-R = NR ▪CCSE = 10-12 |

▪MIS, IST = 74 ▪IST, BVRT - Cutoff level 1 = 90.8 ▪CAMCI = 83.4 ▪ACE - Cutoff <88/100 = 100 ▪ADAS-Cog - Cutoff <75/100 = 85 ▪CAMCOG = 76 for memory section ▪MoCA = 94 ▪S-MMSE = 14 ▪IQCODE = 41 ▪STMS = ≤ 80 ▪MMSE = 31 ▪HDS-R = 92 for the dementia diabetic group ▪CCSE - Cutoff 26/25 = 88.1 |

▪MIS = 84, IST = 81 ▪IST, BVRT - Cutoff level 1 = 52.2 ▪CAMCI = 78.5 ▪ACE - Cutoff <88/100 = 43 ▪ADAS-Cog - Cutoff <75/100 = 83 ▪CAMCOG = 96 for memory section ▪MoCA = 50 ▪S-MMSE = 100 ▪IQCODE = 67 ▪STMS = ≤ 80 ▪MMSE = 96 ▪HDS-R = 74 for the dementia diabetic group ▪CCSE - Cutoff 26/25 = 83.5 |

Tools with the highest specificity rates: ▪MMSE ▪S-MMSE Tests with the highest sensitivities: ▪HDS-R ▪ACE, which decreased depending on cut-off value ▪MoCA for the dementia group and 83% for the MCI group ▪CAMCI ▪CCSE ▪The combination of the MMSE, IST, and BVRT at 90.8% for the first cut-off level. The ACE demonstrated good diagnostic accuracy with AUC=0.98. Xu et al. (2002) found that the CCSE was the best predictive screen in MCI participants for diagnosing all dementia due to its high sensitivity (88.1%) and specificity (83.5%). |

(IST,BVRT)-Isaacs Set Test, Benton's Visual Retention Test. CAMCI-Chinese Abbreviated Mild Cognitive Impairment Test, (ADAS-Cog)-Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale, (S-MMSE)-Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination, (HDS-R)-Hasegawa Dementia Scale-Revised, CCSE-Cognitive Capacity Screening Examination, CAMCOG-Cambridge Cognitive Examination |

| Boustani et al, United States | 61 |

▪MMSE ▪FAQ ▪BIMC ▪BOMC ▪STMS |

DSM-IV | Dementia | Not mentioned. |

▪MMSE = 71-92 ▪FAQ = 90 ▪BIMC = 90 ▪BOMC = 69 ▪STMS = 81 |

▪MMSE = 56-96 ▪FAQ = 90 ▪BIMC = 65-90 ▪BOMC = 90 ▪STMS = 90 |

The MMSE has limited Sp when the cut-point is set for higher Sn. Accuracy of the MMSE changes based upon the patients age, education level and ethnicity and therefore requires adjustment when used. | BIMC-Blessed Information Memory Concentration; BOMC-Blessed Orientation Memory Concentration; FAQ-Functional Activities Questionnaire; STMS-Short Test of Mental Status; DSM-IV-Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition |

Five systematic reviews examining the MMSE found that it took between 4 and 15 min to administer depending upon the severity of dementia [12–16]. One study found a cut point of 17 had a higher specificity (93 %, 95 % CI: 89-96 %) than a cut point of 24 (46 %, 95 % CI: 40-52 %), while the sensitivity fell from 100 % (95 % CI: 95-100 %) to 70 % (95 % CI: 59-80 %) respectively [16].

The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) achieved high sensitivity (100 %, 95 % CI: 70-100 %) and specificity (82 %, 95 % CI: 72-90 %) [12] compared to a clinical reference standard, and took the shortest amount of time (3.16 to 5 min) [12, 14] within primary care. The AMTS was validated for use in general practice [12].

Diagnostic accuracy and physician education

The diagnosis of dementia by FPs varies but is generally low, as reported in 3 different systematic reviews [11, 16, 19]. In an (urban/rural) study, when following usual practice, only half of cases of mild dementia were diagnosed by the FP [19]. In a separate review, un-diagnosed dementia accounted for 50 − 66 % of all cases of dementia in three primary care samples studied [11, 20−22]. Another review reported that the recognition of cognitive impairment in usual practice achieved a detection sensitivity of 62.8 % (95 % CI: 38.0-84.4 %) and specificity of 87.3 % (n = 3; 95 % CI: 84.9-89.4 %) [16]. However, medical record notations mentioning dementia were present in only 37.9 % (95 % CI: 26.8-49.6 %) and FPs recorded a definitive dementia diagnosis in the medical record in only 10.9 % (95 % CI: 6.8-15.7 %) of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) cases [16].

Five of six studies found that FPs had an increased likelihood of suspecting dementia after attending an educational seminar [23, 24]. One study found that the length of the educational seminar impacted the degree of knowledge about dementia management [24].

Management of dementia

Decision aids, advanced care planning (ACP), collaboration with a case manager (CM) and practice guidelines are all interventions with variable impact on helping facilitate the management of dementia in primary care [23, 25−29] (Table 2). A CM in particular, such as a nurse specialized in care of older adults, can be an asset to a primary care team with the collective goal of collaborating towards meeting the needs of the patient-caregiver dyad [30]. In the case management intervention group of a randomized controlled trial, neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia decreased (Mean Effect Size (MES) = 0.88), as well as the numbers of hospital (MES = 0.66) and emergency department admissions (MES = 0.17) [26]. However, it was found that there was a lack of successful implementation of a CM into care teams within primary care because of the absence of CMs within the primary care setting, and 52 % of CMs reported ineffective communication between the CM and FPs [26].

Table 2.

Case management interventions and corresponding comparators and outcomes from the literature included in this systematic review

| Authors, Country | Number of studies included in systematic review | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sivananthan et al, Canada | 12 |

7 dementia care processes recommended by best practice guidelines: ▪Formal memory testing ▪Imaging ▪Laboratory testing ▪Interventions ▪Counseling ▪Community service ▪Specialist referrals |

Clinical services provided by physicians to older adults diagnosed with dementia. |

▪8 out of 12 studies reported that <60% of physicians conducted formal memory testing, while 3 studies reported <15%, and 1 study <4% ▪33% to 91% of family physician's prescribed medications for dementia and consequent behavioral problems ▪33-80% of physicians reported the use of CT or MRI as a diagnostic tool, and >75% used blood work ▪2 studies reported that >80% of physicians provided counseling. |

| Khanassov et al, Canada | 23 |

Case Management interventions comprising all components identified by the Case Management Society of America: ▪Case finding and screening ▪Assessment ▪Care planning ▪Implementation and management ▪Monitoring ▪Review |

No comparator |

▪Only 63% of case managers clearly explained their role to the patient-caregiver dyads while 25% did not give any detail during assessment ▪52% of case managers indicated that poor communication with healthcare providers negatively affected their work ▪Limiting factors to case management implementation were: insufficient knowledge of diagnostic tools, absence of training, and the absence of the case manager in the primary care setting. |

| Davies et al, United Kingdom | 10 | Decision-making interventions with decision aids in dementia care (i.e. audio guided booklet, a printed decision aids about dementia and feeding; a living with dementia Guiding Options for Living with Dementia (GOLD) book; DECIDE intervention: a guided decision aid participants read and complete with support of decision coach to assist in making decisions regarding care home placement, video decision aid and structured meeting between surrogate decision maker and interdisciplinary care plan team; a video decision aid and audio description of advanced dementia) |

▪The majority of studies used a control group ▪One study used solely listening to a verbal narrative of the disease. |

Place of care: ▪DECIDE decreased decisional conflict in caregivers ▪GOLD showed less of an increase in burden and greater increase in the knowledge of caregivers Goals of care: ▪A video decision aid combined with a structured meeting improved communication between caregivers and professionals and improved the concordance on the goals of care after 9 months Meta-analysis: ▪Two RCTs (N=72) included. ▪Decision aids are effective in decreasing decisional conflict in caregivers (standardized MD=− 0.50, 95% CI [ − 0.97, − 0.02]). This suggests increased confidence in decision-making and understanding of the decisions. ▪Decisional conflict was measured using the Decision Conflict Scale at 3 months post intervention. |

| Tilburgs et al, Australia | 16 | Advanced care planning (ACP) | No comparator |

Facilitators for ACP: ▪An early start while cognitive decline is mild. ▪Inclusion of all stakeholders and a good relationship between the GP, patient, and family carers. ▪Discussion of social and medical issues aimed at maintaining a normal life. ▪Decision aids that provide information and structure which contribute to decision making. Barriers for ACP: ▪Uncertainty about the timing of ACP. ▪How to plan for an uncertain future. ▪Lack of knowledge about dementia and patient's lack of knowledge of diagnosis. ▪Bad relationships among stakeholders. ▪Stress/fear caused by ACP. ▪Who should take initiative for ACP. ▪Difficulties assessing the dementia patient's decisional capacities. ▪Changing preferences. |

| Mukadam et al, United Kingdom | 13 |

Interventions intended to increase the detection of : ▪Dementia ▪Suspected dementia ▪People presenting with memory complaints |

RCT: ▪Control groups. Non-randomized studies and pre-post study designs: ▪Comparison groups. |

▪2 of 3 RCTs of physician education found group educational interventions increased the likelihood of physicians suspecting dementia. ▪Non-randomized study findings suggest that clinician education in primary care interventions can increase the proportion of patients in whom physicians suspect dementia; untargeted community leaflet campaigns did not increase dementia diagnosis rates. ▪Pre-post comparison studies showed no positive effects for individual clinician training, group training with a routine screening programme or a targeted leaflet campaign. An increased number of memory clinics correlated with an increased number of dementia diagnoses. |

| Khanassov et al, Canada | 43 |

Case management (CM): ▪Assessment ▪Care planning ▪Implementation ▪Management ▪Regular follow-up |

RCT: ▪Control group Qualitative studies: ▪No control |

RCT evidence: ▪4/10 trials showed a decrease in the frequency of behavioral symptoms of dementia in the CM intervention group (mean effect size 0.88), while 2/7 reported a decrease in depression symptoms. ▪No effect on cognition and perceived health was observed. ▪8/11 trials found no effect on institutionalization. ▪Hospital admissions decreased (MES=0.66) in 2/5 studies. ▪Decreased ER admission was observed in 1/3 studies (effect size: 0.17) and a decrease in length of hospital stay was shown in both of the studies that evaluated this outcome (MES=1.06). ▪For caregivers, 5/10 studies showed a decrease in depression (MES=0.68) and 4/11 showed a decrease in burden (MES=0.5). Barriers to implementation of CM using outcome matching: ▪Intervention durations being too short. ▪Need for high-intensity CM. ▪Scarce communication. ▪Case manager and physician in different locations. ▪Lack of healthcare providers with geriatric training. Addressing these barriers correlated with better outcomes, as studies addressing more barriers resulted in more positive outcomes (agreement κ=0.94; CI, 0.82-1.1). |

| Perry et al, Netherlands | 6 | Series of seminars and the appointment of dementia care managers. |

Control groups in studies: ▪Clinical practice guidelines for dementia received by mail ▪No training ▪No seminars ▪No training and no dementia care managers ▪Short, partly interactive seminar on dementia diagnostics (3 hours). |

▪Intervention clinics demonstrated better health-related quality of life (QoL), overall quality of health care in patients, family caregiving quality, social support and more family caregivers reported receiving all the help they needed. ▪The health-related QoL of the caregiver did not increase. ▪Higher proportions of patients were newly diagnosed with dementia following educational workshops and computerized Decision Support System (DSS) group compared to the control group. ▪After a 2-h seminar for physicians there were higher rates of 'suspected dementia' and lower rates of both 'uncertain' and 'non-suspected' diagnoses when compared to the control group. ▪Both the mean compliance per patient to the total set of 23 quality indicators, and the compliance per indicator for 21 of 23 quality indicators, were better in intervention clinics than in control clinics. ▪Physicians gained more knowledge after a 5-h seminar than a 3-h seminar. ▪After 9-months, more physicians in the intervention group correctly answered 2 questions about decision-making compared to the control group. Those in the intervention group more strongly agreed that 'Older patients with dementia are difficult to manage in primary care' than the PCPs in the control group. |

Only one systematic review looked at pharmacological treatments in the context of primary care [11]. There was no clinically important difference observed on neuropsychiatric symptoms between patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease taking cholinesterase inhibitors versus placebo [11].

Supporting caregivers of people with dementia

FPs reported feeling highly involved in dementia care [31]. However, family caregivers reported that communication with the FPs was unsatisfactory, specifically around awareness of daily care problems (e.g. neuropsychiatric symptoms) [31]. The primary care educational intervention, Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs) (REACH VA), involves a trained coach who provides sessions to the caregiver on topics relating to self-care, problem solving, mood management and stress management [32]. REACH VA was successful at increasing carer ability to manage problem behaviours and improved outcomes for caregivers, such as decreased burden, depression and caregiving frustrations [30, 31]. A meta-analysis showed that 58 % (95 % CI: 43-72 %) of family caregivers were in favor of early dementia diagnosis, 50 % (95 % CI: 35-65 %) needed education on dementia, and 23 % (95 % CI: 17-31 %) needed in-home support [33].

Discussion

This systematic review of systematic reviews identified evidence to inform processes for diagnosis and management of dementia within primary care. While the diagnostic accuracy of a tool may be high, the time taken to administer the tool and copyright limitation for tool use are also important to consider in the context of a busy primary care office. The MMSE, which is copyrighted, may not be the best test for use in general practice. Instead, the AMTS appears to be the most suitable tool for use in a busy primary care office, as it has good diagnostic accuracy, does not appear to be copyright protected and takes less time to administer than the MMSE [12, 14, 15]. The Mini-Cog is also quick to administer, and a Cochrane systematic review evaluating the Mini-Cog across care settings recommended that the Mini-Cog be used initially as a case finding test to identify patients who would benefit from additional cognitive evaluations for dementia [34]. However, the sensitivity of the Mini-Cog may not be high enough to be considered useful in primary care [17], as too many cases would be missed.

The current literature suggests that the implementation of case management directly into the primary care setting can be of great benefit to the patient-caregiver dyad, as well as to the health care system. The CM can help facilitate the advanced care planning process [29], as well as decrease the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia, symptoms of depression, hospital admissions and length of stay in hospital; caregivers can also benefit by experiencing decreased burden and depression [26]. A Cochrane review evaluating the effectiveness of case management in community settings lends support to dementia case management, finding that carer burden decreased and fewer patients where institutionalized after 6 months [35]. Further, there was a reduction in residential home and hospital use after 6 months of case management implementation [35]. There is however a lack of evidence related to cost effectiveness of case management. Facilitating successful case management and advanced care planning includes early implementation while cognitive decline is mild, involving all stakeholders (caregiver, patient, family and FP), and fostering a good relationship between the FP and patient-caregiver dyad [29]. The CM should be physically present in the primary care setting, clearly explain their role to all stakeholders, implement high-intensity case management, and communicate frequently to all stakeholders in order to ensure positive outcomes for the patient-caregiver dyad [26, 27].

Combining educational seminars for FPs with dementia case management may be the best management strategy [23, 24]. Educational interventions focused on dementia diagnosis and management in the context of primary care increased the likelihood of FPs suspecting dementia, while also improving the experience of the family caregiver and the patient [23, 24].

There was limited evidence concerning the use of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of dementia within the primary care setting. Unfortunately, many pharmacologic studies do not focus on primary care or FPs, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the approach to take regarding the use of medications in this context. One systematic review found no clinically important differences between groups receiving cholinesterase inhibitors and those receiving a placebo in the development of behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease [11]. Similarly, cholinesterase inhibitor use was found to have uncertain clinical benefit in a recent systematic review that explored the benefits and harms of prescription drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer disease, regardless of care setting [36]. This recent review also found limited benefit for memantine.

Conclusions

The AMTS is suitable for detecting dementia within primary care given its high sensitivity and short administration time. To improve dementia identification, FPs should participate in educational interventions. Incorporation of CMs into the primary care team can help with dementia management and result in improved outcomes. There is limited evidence supporting the benefit for pharmacological treatments in the context of primary care.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of this systematic review of systematic reviews includes the exclusion of possibly relevant pharmacological reviews, given the fact that we focused on studies conducted in the primary care setting. Future pharmacological studies conducted in the specific context of primary care are needed. Additionally, the results from our review are limited to literature from countries that clearly distinguish primary care from specialist care, given the focus of the search strategy. Lastly, many of the studies included within the identified systematic reviews inappropriately used the MMSE as a reference tool when determining the sensitivity and specificity of various screening tools. Further studies should compare commonly used screening tools within primary care to a recognized gold standard.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Helen Lee Robertson, MLIS, Health Sciences Library, University of Calgary for assisting in the development of the systematic literature search.

Support

B. Fernandes was funded as an Undergraduate Summer Research Student by the Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Calgary and a MITACS studentship. J. Holroyd-Leduc is the University of Calgary Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine.

Prior Presentation

None.

Abbreviations

- FPs

Family physicians

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- AMTS

Abbreviated Mental Test Score

- ACP

Advanced Care Planning

- CM

Case Manager

- MES

Mean Effect Size

- REACH VA

Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (Department of Veterans Affairs)

Authors’ contributions

All 3 authors derived the study. BF and JHL reviewed all retrieved citations and manuscripts. All 3 authors analysed the findings. BF drafted the manuscript; JHL and ZG provided critical edits. All 3 authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

B. Fernandes was funded as an Undergraduate Summer Research Student by the Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Calgary and a MITACS studentship. J. Holroyd-Leduc is the University of Calgary Brenda Strafford Foundation Chair in Geriatric Medicine. The funders had no role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1: Appendixes 1 and 2.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate:

Not applicable.

Consent for publication:

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Brooklynn Fernandes, Email: Brooklynn.fernand1@ucalgary.ca.

Zahra Goodarzi, Email: zahra.goodarzi@albertahealthservices.ca.

Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, Email: jayna.holroyd-leduc@ahs.ca.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia WHO. World Health Organization Dementia. Published September 19, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia].

- 2.Parmar J, Dobbs B, McKay R, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia in primary care: exploratory study. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2014;60(5):457–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra A, Cavalieri TA, Libon DJ. Dementia Screening Tools for the Primary Care Physician. 2007;15(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ismail Z, Black SE, Camicioli R, et al. Recommendations of the 5th Canadian Consensus Conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16(8):1182–95. 10.1002/alz.12105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Pimlott NJG, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. Family physicians and dementia in Canada: Part 2. Understanding the challenges of dementia care. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2009;55(5):508–509.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strings attached: CADTH database search filters. Strings attached: CADTH Database Search Filters. Published 2016. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/strings-attached-cadths-database-search-filters#syst

- 8.Yokomizo JE, Simon SS, de Campos Bottino CM. Cognitive screening for dementia in primary care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1783–1804. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. Published online September 21, 2017:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Abd Razak MA, Ahmad NA, Chan YY, et al. Validity of screening tools for dementia and mild cognitive impairment among the elderly in primary health care: a systematic review. Public Health. 2019;169:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boustani M, Peterson B, Hanson L, Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for Dementia in Primary Care: A Summary of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(11):927. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodaty H, Low L-F, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia screening instrument for general practitioners to use? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(5):391–400. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216181.20416.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online January 13, 2016. 10.1002/14651858.CD011145.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cullen B, O’Neill B, Evans JJ, Coen RF, Lawlor BA. A review of screening tests for cognitive impairment. J Neurol Neurosurg Amp Psychiatry. 2007;78(8):790–799. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.095414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lischka AR, Mendelsohn M, Overend T, Forbes D. A Systematic Review of Screening Tools for Predicting the Development of Dementia. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil. 2012;31(3):295–311. doi: 10.1017/S0714980812000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Pentzek M. Clinical recognition of dementia and cognitive impairment in primary care: a meta-analysis of physician accuracy: Clinical recognition of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(3):165–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seitz DP, Chan CC, Newton HT, et al. Mini-Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias within a primary care setting. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online February 22, 2018. 10.1002/14651858.CD011415.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Smith T, Cross J, Poland F, et al. Systematic Review Investigating Multi-disciplinary Team Approaches to Screening and Early Diagnosis of Dementia in Primary Care – What are the Positive and Negative Effects and Who Should Deliver It? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;15(1). 10.2174/1567205014666170908094931 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Dungen P, Marwijk HWM, Horst HE, et al. The accuracy of family physicians’ dementia diagnoses at different stages of dementia: a systematic review: The accuracy of family physicians’ dementia diagnoses. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Published online May 2011:n/a-n/a. 10.1002/gps.2726 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Eefsting JA, Boersma F, Van den Brink W, Van Tilburg W. Differences in prevalence of dementia based on community survey and general practitioner recognition. Psychol Med. 1996;26(6):1223–1230. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olafsdóttir M, Skoog I, Marcusson J. Detection of dementia in primary care: the Linköping study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2000;11(4):223–229. doi: 10.1159/000017241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL. The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(19):2964–2968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukadam N, Cooper C, Kherani N, Livingston G. A systematic review of interventions to detect dementia or cognitive impairment: Systematic review of interventions to detect dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):32–45. doi: 10.1002/gps.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry M, Drašković I, Lucassen P, Vernooij-Dassen M, van Achterberg T, Rikkert MO. Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/gps.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies N, Schiowitz B, Rait G, Vickerstaff V, Sampson EL. Decision aids to support decision-making in dementia care: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(10):1403–1419. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanassov V, Vedel I, Pluye P. Barriers to Implementation of Case Management for Patients With Dementia: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):456–465. doi: 10.1370/afm.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khanassov V, Pluye P, Vedel I. Case management for dementia in primary health care: a systematic mixed studies review based on the diffusion of innovation model. Clin Interv Aging. Published online June 2014:915. 10.2147/CIA.S64723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Sivananthan SN, Puyat JH, McGrail KM. Variations in Self-Reported Practice of Physicians Providing Clinical Care to Individuals with Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1277–1285. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilburgs B, Vernooij-Dassen M, Koopmans R, van Gennip H, Engels Y, Perry M. Barriers and facilitators for GPs in dementia advance care planning: A systematic integrative review. Arendts G, ed. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0198535. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Greenwood N, Pelone F, Hassenkamp A-M. General practice based psychosocial interventions for supporting carers of people with dementia or stroke: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0399-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, Delepeleire J. What is the role of the general practitioner towards the family caregiver of a community-dwelling demented relative?: A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27(1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/02813430802588907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Published 2020. https://www.caregiver.va.gov/REACH_VA_Program.asp

- 33.Khanassov V, Vedel I. Family Physician-Case Manager Collaboration and Needs of Patients With Dementia and Their Caregivers: A Systematic Mixed Studies Review. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):166–177. doi: 10.1370/afm.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holsinger T, Plassman BL, Stechuchak KM, Burke JR, Coffman CJ, Williams JW. Screening for Cognitive Impairment: Comparing the Performance of Four Instruments in Primary Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1027–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reilly S, Miranda-Castillo C, Malouf R, et al. Case management approaches to home support for people with dementia. Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online January 5, 2015. 10.1002/14651858.CD008345.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Fink HA, Linskens EJ, MacDonald R, et al. Benefits and Harms of Prescription Drugs and Supplements for Treatment of Clinical Alzheimer-Type Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(10):656–668. doi: 10.7326/M19-3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article in Additional file 1: Appendixes 1 and 2.