Abstract

Background

Shared decision‐making (SDM) is considered the “final stage” that completes the implementation of evidence‐based medicine. Yet, it is also considered the most neglected stage. SDM shifts the epistemological authority of medical knowledge to one that deliberately includes patients' values and preferences. Although this redefines the work of the clinical encounter, it remains unclear what a shared decision is and how it is practiced.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to describe how healthcare professionals manoeuvre the nuances of decision‐making that shape SDM. We identify barriers to SDM and collect strategies to help healthcare professionals think beyond existing solution pathways and overcome barriers to SDM.

Methods

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted with 68 healthcare professionals from psychiatry, internal medicine, intensive care medicine, obstetrics and orthopaedics and 15 patients.

Results

This study found that healthcare professionals conceptualize SDM in different ways, which indicates a lack of consensus about its meaning. We identified five barriers that limit manoeuvring space for SDM and contest the feasibility of a uniform, normative SDM model. Three identified barriers: (a) “not all patients want new role,” (b) “not all patients can adopt new role,” and (c) “attitude,” were linked to strategies focused on the knowledge, skills and attitudes of individual healthcare professionals. However, systemic barriers: (d) “prioritization of medical issues” and (e) “lack of time” render such individual‐focused strategies insufficient.

Conclusion

There is a need for a more nuanced understanding of SDM as a “graded” framework that allows for flexibility in decision‐making styles to accommodate patient's unique preferences and needs and to expand the manoeuvring space for decision‐making. The strategies in this study show how our understanding of SDM as a process of multi‐dyadic interactions that spatially exceed the consulting room offers new avenues to make SDM workable in contemporary medicine.

Keywords: clinical guidelines, evidence‐based medicine, healthcare, patient‐centered care

1. INTRODUCTION

There is consensus about the importance of implementing shared decision‐making (SDM) in the health system. First, SDM is seen as a framework that preserves patients' right to self‐determination.1 Second, SDM is key to integrate the three epistemic domains of evidence‐based medicine (EBM): best available evidence, clinical expertise and patient's preferences.2, 3 While SDM was conceptualized at a time when EBM was still in its infancy, present day their relationship still remains elusive.3 Frequently cited models such as the three‐talk model developed by Elwyn et al4, 5 embed EBM in decision‐making through a series of steps starting with the facts during what is referred to as “option talk.” In the subsequent step, values and preferences are discussed that together inform in the final step of shared decision‐making (SDM). Although this neatly outlines how the instrumental input of EBM is divided across different phases of decision‐making, it does little to address the integration of these epistemologically different inputs, which seem to remain judgements of the individual healthcare professional.* Indeed, SDM is considered by some as the most neglected component of EBM.3, 6, 7

Stiggelbout et al8 note that for “preference‐sensitive decisions,” decisions for which there is no (scientific) certainty about the optimal strategy, SDM should be the norm. However, the implementation of SDM has not caught up to the ubiquity of uncertainty that characterizes contemporary medicine.6 Previous studies9, 10, 11 have highlighted the lack of a shared, coherent understanding of SDM as an important barrier that obstructs effective implementation of SDM into medical practice. Although SDM redefines the work of the clinical encounter,12 it remains unclear what a shared decision is and how it is practiced.13, 14 Lloyd et al9 conclude that this “patchy coherence” warrants further exploration of sense‐making work, that is, actors' exploration of the differences between the newly proposed practice and already established practices.15

Building on previous studies, we examine how healthcare professionals “make sense” of SDM as a practice, inspired by the Normalization Process Theory (NPT). NPT describes the implementation of practices as “resulting from people individually and collectively, to enact them”15 (p2) and denotes that practices are socially shaped to make them workable in specific contexts.15 As such, building coherence between SDM and established practices requires actors to collectively invest meaning in SDM—i.e. “make sense” of SDM in practice.

This study explores the sense‐making work done by healthcare professionals working in different medical disciplines in the Netherlands and accompanying implementation issues. First, we explore how healthcare professionals conceptualize SDM and how they manoeuvre the nuances of decision‐making that shape SDM. Furthermore, this study presents a set of strategies collected from different disciplines that may help healthcare professionals to think beyond existing solution pathways and overcome barriers to SDM in order to bridge the gap between the philosophy and practice of EBM.

2. METHODS

This qualitative study on barriers and strategies related to the implementation of SDM was set up at a teaching hospital located in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

2.1. Data collection

Eighty three (83) semi‐structured interviews were conducted between February and July 2015 with physicians (n = 28), medical residents (n = 23), nurses (n = 12), and department managers (n = 5) working in psychiatry, internal medicine,† general surgery, intensive care medicine, obstetrics/gynaecology and orthopaedics. Interviewees were asked to describe aspects of SDM and what barriers they encountered to implement SDM into practice.

In addition, 15 patients from psychiatry and oncology were interviewed about recent experiences with medical decision‐making and barriers that they had encountered to participate in decision‐making. Oncology was selected, because this discipline is characterized by a myriad of preference‐sensitive decisions.‡ 16 In psychiatry, on the other hand, SDM is still in its infancy.1, 17 SDM may be perceived to require a difficult balance between patient safety and patient autonomy18 that could leave psychiatrists with little manoeuvring space for SDM.

3. ETHICS STATEMENT

The study protocol was submitted to the board of directors of the hospital who, advised by the Advisory Committee on execution of scientific research, granted ethical approval on 31st of March 2015 for conducting interviews with patients. The interviews with healthcare professionals were exempt from ethical approval. All study participants signed informed consent forms prior to the interviews.

3.1. Data analysis

Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. All the interviews were summarized and sent to the interviewee for member check. Interviews were coded inductively to elicit themes present in the SDM definitions. The analysis focused on unravelling how physicians conceptualized SDM and how they manoeuvre barriers that affect the implementation of SDM in practice.

4. RESULTS

The results are divided into two sections. First, we outline how healthcare professionals conceptualize SDM. Second, we describe barriers that affect the implementation of SDM and we describe a set of strategies that we identified in the interview data that could help healthcare professionals cope with these barriers and make SDM workable in medical practice.

4.1. Conceptualizations of SDM

In order to examine how respondents conceptualize SDM, we asked respondents to provide a definition of SDM. Note that only a few respondents had been formally trained about SDM. Still, most respondents believed that SDM was already applied in regular practice, albeit not practiced in a uniform way. The three varieties of SDM used to categorize respondent's conceptualizations: (a) SDM as a negative right, (b) Informed decision‐making and (c) Tailored partnership, indeed show that there is no uniform conceptualization. Yet, these diverse conceptualizations also expose the intricate nuances of decision‐making and tensions that may contest the possibility and desirability of one uniform SDM conceptualization.

4.1.1. SDM as a negative right

Respondents frequently see patient input as a (negative) response to guideline‐based treatment options. Two respondents explicitly described that SDM meant giving the patient a choice in treatment, in case “the patient does not agree with our advice.” This description resonates with what Azevedo & Dall'Agnol19 describe as SDM being a “negative right” that stems from the notion that patients cannot be forced to submit to any course of action against their will. Another assumption of this framework, referred to as the “Professional Practice Standard,” is that decision‐making is based on “what any reasonable expert would do,” which excludes patients as active agents in decision‐making.19 Indeed, several respondents mentioned examples that show the difficulty of reconciling SDM with guideline adherence, making attempts to share decisions feel contrived.

“You give patients certain options that they can choose from, because we want to give them a choice. Then you tell the patient: ‘[for priming] you can choose between a balloon and Misoprostol.’ But maybe the patient does not even want to be primed.” (Obstetrician).

According to a gynaecologist, this tension is enhanced by the involvement of different interests: “[We cannot always simply grant patient's wishes for example when the patient refuses treatment], because we have to consider the health of the mother and the child.” The quotes illustrate the tensions between patient autonomy and physicians' primary concern for beneficence and non‐maleficence. Thus, it raises the question: “can a patient always be involved in decision‐making when treatment is clinically indicated?” Not taking medical action directly opposes the fundamentals of medical professionals.

The role that clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) play should be perceived as part of larger system clinical and financial accountability (eg, reimbursement schemes). We further elaborate on the systemic contextuality of SDM in the fourth barrier.

4.1.2. Informed decision‐making

The first variety shows how CPGs directly inform the decision to be made, leaving SDM in an ambiguous place. The second variety, usually framed as a “higher order” of SDM, alternates between unilateral flows of information from physician to patient during information provision, and from patient to physician regarding the selection of treatment. One physician describes himself sitting behind an “advice desk”: “I inform patients about the options, but the patient decides. We enthusiastically suggest options, but patients are not obliged to follow our advice.” This description suggests that decision‐making is left up to the patient while physicians act only as “conduits of medical knowledge,” which resonates with what Charles et al20 define as “informed decision‐making.”

Although some respondents suggested providing only the options to patients, most respondents preferred to give advice about the preferred or most suitable option as well. Psychiatrists mentioned that in clinical settings, there is a different understanding of autonomy compared to non‐clinical settings,21 as patients' judgements rely on the guidance that physicians provide. Such doctor‐patient exchanges contest the idea that SDM can be broken up into distinct phases found in frequently cited SDM models.4, 5

4.1.3. Tailored partnership

The third variety, described by several respondents, tailors decision‐making to the patient's needs and preferences. A psychiatry resident notes that: “It is very difficult to speak of ‘the patient’ (…). It is very diverse. [Your approach to decision‐making] will depend on a variety of things, patient's age, the expectations of the physician, the severity of the disease, the diagnosis.” A few other responses resonated with this idea of tailoring decision‐making with some suggesting that this should be the guiding principle SDM education. Although these respondents equate tailored decision‐making with SDM, it was difficult to discern whether the process of tailoring decision‐making to the patient is itself a shared process—even the decision to adopt a paternalistic approach being discussed and agreed upon beforehand.

4.2. Barriers and strategies

This next section outlines five barriers described by healthcare professionals and patients followed by set of strategies collected from different disciplines that may help healthcare professionals to think beyond existing solution pathways and overcome barriers to SDM.

4.2.1. Barrier 1: “Not all patients ‘want’ new role”

SDM in literature is defined as an ongoing collaboration between healthcare professionals and patients. However, healthcare professionals report that not all patients “want”§ to be involved and instead adopt a passive role. A literature review in oncology showed that both physicians and patients think that physicians are better equipped to make decisions on behalf of patients. Although this may hold true for medical considerations, it still may be difficult to arrive at the “right” decision for a particular patient. A physician assistant in oncology describes: “sometimes that question is literally asked. Such as ‘what would you do?’ or ‘what should I do?’ or ‘what is the best?’. Well, that's very often impossible to be answered at all.” Although this barrier was frequently mentioned, no strategies were listed for patients that (for whatever reason) do not want to participate.

4.2.2. Barrier 2: Not all patients “can” adopt new role

One of the barriers related to patients' ability to participate is patients' unawareness of their options. Oncology patients reported not to be aware of any treatment options and that they simply agreed to the recommendation of the oncologist.

[The physician told me that] the tumour will respond quickly to chemotherapy and [so I agreed]. (…) You do not think any more about what else is possible. (…) Are there other treatment possibilities? (…) You do not ask that anymore. The physician has decided. (Oncology patient)

The patient describes that he does not feel like an equal participant in decision‐making and hence refrains from deliberating options. The negative consequences of experienced inequality in the doctor‐patient relationship were sparsely mentioned by patients, and were never explicitly reported by healthcare professionals.

Some patients mentioned that they at least want to understand the choice of treatment, even when they do not necessarily object to a paternalistic approach. Receiving insufficient information or not being able to understand information are closely related to patient's unawareness or impeded comprehension of their options. These barriers are reinforced by physician's assumption that patient have understood the provided information.

Strategies

Strategies often included asking questions to check understanding that physicians had been taught during communication training: “when you go home, what will you tell your husband about what you heard [during the consult]?” Besides checking understanding, which pertains more to the exchange of information, other strategies focused on building a trusting relationship with the patient to support patients to participate. Active listening and adapting the communication style to the patient and were mentioned as ways to promote trust. Although trust is considered a condition, it is by no means a guarantee for patient participation in decision‐making and may even encourage patients to remain passive, as they trust the doctor to know what is best. Therefore, other strategies that explicitly encourage patients to participate in decision‐making and assure them that they make the final call were mentioned as well. For example, some physicians try to instruct the patient about their rights: “[I tell patients:] ‘it is your choice to make and you can make a different decision [than me].” Furthermore, four respondents mentally prepare patients for decision‐making by starting their consultation with a summary of patient's status. Nine respondents mentioned eliciting patient preferences as a possible strategy “Sometimes you try it together a little bit: ‘what do you want?’, ‘What are your expectations?’”. Hence, trust and explicitly inviting patients to participate can serve as complementary elements to diminish imbalances in the doctor‐patient relationship.

4.2.3. Barrier 3: Attitude

The previous section briefly referred to skills learned during communication training as a strategy to promote SDM. However, more important than training are inborn traits and attitude that just not every doctor has, as mentioned by some respondents.

There is scepticism about (…) the “soft side [of medicine”], it is not interesting to them (Physician)

“You have people doctors (…) people persons,” but you also have real doctors with a bit of arrogance (Physician assistant obstetrics)

Similarly, a resident described how attitudes toward patient involvement in psychiatry could negatively affect SDM. “I think these people should get more rest and space so they can muster the courage to say what they want, and [that we don't think] that because they are psychiatric patients, they cannot choose anything.”

Strategies

A strategy that could be promising with regard to attitude entails strengthening the reflective ability to view cases from different perspectives. We explored the potential contribution of the moral case deliberation (MCD) method as a tool for reflection in 12 interviews. A MCD builds on exploring the norms and values of the stakeholders involved in a specific case. Participants are taught to explicate the considerations that underlie their final decision, making the process of decision‐making more deliberate and transparent according to respondents. Participants noted that attending a MCD session led to a shift in the conversational tone from one that was commonly about convincing the other toward respecting and understanding each other's perspective. This shift may positively contribute to SDM in the sense that MCDs help to really “hear” the other and consider each other's perspective before reaching a decision. Finally, multiple respondents described that they usually make many treatment decisions without being aware of other's perspectives: [During the MCD] it became obvious that the ACTUAL thoughts of the patient were not clear. […] We did not focus on his norms and values for even a second.” This quote resonated with remarks from other participants who concluded that in the future they would elicit patient's preferences sooner.

Note that we acknowledge that attitude toward SDM can both be an individual trait as well as a systemic barrier, emphasizing that the situated practice of sense making is embedded in cultural and structural norms (cf. Schuitmaker).

4.3. Systemic barriers and strategies

The barriers and strategies described so far situated sense making at the interface between individual physicians and patients, complemented by strategies that focus on improving professionals' knowledge, skills and attitudes. The barriers described below illustrate how sense making is embedded within the system. The fourth barrier illustrates how CPGs may impose on decision‐making leading to the prioritization of medical issues over the right to self‐determination. The fifth barrier illustrates how time constraints that are imposed by a reimbursement system of fixed 10‐minute consultations render strategies related to knowledge, skills and attitudes insufficient.

4.3.1. Barrier 4: Prioritization of medical issues

When only one medical option is available, there is no real decision for the patient to be involved in, several respondents noted, in line with “SDM as a negative right.” However, it touches upon the systems built around CPGs that reinforce clinical and financial accountability. An obstetrician reported that SDM is facilitated when patient's wishes align with protocols. When patient's preferences deviate, however, physicians can find themselves split between adhering to CPGs or trying to keep the patient satisfied by resorting to “demand driven care.” The quote below illustrates this and shows how such decisions are entrenched in a larger system of cost concerns and reimbursement schemes.

Do I have to keep the patient satisfied? Or do I have to work according to the guidelines and try to save costs? The patient can choose to return to his GP to request an MRI; the GP may then refer the patient to another hospital. In that case, the healthcare costs will be even higher (…) so should I then ignore guidelines and give the patient what he or she wants? (Physician)

The limitations imposed by CPGs and the systems built around it raise questions about how different principles of patient‐centred care and EBM can be balanced in a shared doctor‐patient deliberation.

Strategies

Respondents working in psychiatry and oncology emphasized that patient involvement is always possible, if only to acquire consent. A psychiatrist noted that patients should not be underestimated; even if patients are partially incapacitated due to illness, it is still important to provide a good explanation concerning what treatment the physician wants to prescribe. Respondents working in inpatient oncology described efforts to involve patients in every way they can.

“As a doctor, you should explain the things you do. However, in this department, I find it striking how much we discuss with patients, including the very small things: (…) that you have to administer something via an IV, or that you prescribe pills that look different from what the patient is used to. I learned, here more than anywhere else, to discuss everything [with the patient], which, of course, is very time consuming” (Physician Assistant oncology)

The exchange of information was also described as a means to give patients a sense of control. This approach resonates with the notion of “procedural justice”—concerned with the perceived fairness of decision‐making procedures. Procedural justice theorists posit that fair procedures reflect respect, trust, impartiality and the opportunity to have a voice in decision‐making.24, 25 Described procedural justice strategies allow room for patients to object or otherwise respond, thus fostering a bilateral partnership. Especially in outpatient psychiatry, it is important that patients support the decision made, because the success of therapy relies on patient's commitment and efforts to work on their mental health. In any way, the chances of successful treatment and recovery can be improved by always asking patients how they feel about the advised treatment and whether it fits into their life, a psychiatrist suggested. In addition, an oncologist noted that such questions help to consider and incorporate the differences in patients' perceptions of the impact of the treatment and its potential side effects.

Consent and patient participation not only rely on the information provided, but also, on how this information is conveyed, residents and physicians in oncology emphasized. A resident, for example, highlighted the importance of managing patient's expectations with regard to treatment options and suggested additional training to inform patients more honestly and realistically. “As a doctor, you might want it to be better than it is. […] I think sometimes we can say it all really is not quite so nice if you're constantly on chemo.” In addition, an oncologist described that the way options are discussed with the patient is done with the patient's interest in mind.

I am aware that I am steering. The patient is 69, [chemotherapy] will be hard for her to endure and she will not be able to finish the treatment. In that case, I focus more on the fact that chemotherapy is a heavy therapy (…) I do mention the 5% extra survival rate but do not dwell on it. Because sometimes you have to protect patients.

What respondents did not explicitly mention is that abovementioned strategies can be incorporated into CPGs,** thus embedding SDM into the systems of accountability built around CPG adherence.

4.3.2. Barrier 5: Lack of time

So far, the strategies have focused on individual physician‐patients interactions. However, the feasibility of these strategies is constrained by the limited availability of time—most apparent in cases of immediate crisis. Respondents in emergency obstetrics and oncology noted that immediate crises are actually quite rare. Still, time pressure may hinder patients to be given the necessary time to digest information. An oncologist, for example, describes that patients often feel torn between emotionally digesting the diagnosis while at the same time feeling that they need to start treatment immediately.

Strategies

An oncologist and a surgeon suggested “stepping on the brakes” to give patients time to process. While time is generally in short supply, professionals from oncology, emergency obstetrics and psychiatry stressed that patient's emotional and cognitive capacity can be compromised, affecting their ability to digest information.

If people have metastatic cancer, chemotherapy can easily start a week later. I think for shared decision‐making, and for accepting the treatment, it is very important that you take your time (Oncologist).

Although consulting time is often in the forefront of discussions about lack of time, oncologists stressed that longer consultations would only wear on patients: “No, there is no need for more time [per consult] (…) [Because] a person can listen for max half an hour. It is a lot [to take in all at once]”. Professionals and patients in outpatient psychiatry also reported on the risk of information overload. Consequently, strategies were also sought outside of the consulting room. A psychiatrist mentioned that he usually schedules follow‐up consults and sends his clients home with specific questions that they can ponder in the meantime as input for the follow‐up consult. This idea of having patients prepare in advance of consultation was supported by many healthcare professionals. Some referred to the use of online tools, such as decision aids and online information platforms that patients could consult. Respondents saw the advantage of such tools mainly in terms of freeing up time to deliberate options during consultation or using the tools in the consulting room to make sure that patients receive the same information. Nevertheless, none of the respondents reported using decision aids in practice. One respondent critically remarked that decision aids could be used mainly for gathering information. Nevertheless, making sense of the information in relation to one's own circumstances goes beyond clinical indicators, thus limiting the scope of what such tools can be used for.

Decision support studies, as far as I have read them, they have not been examined or considered the coping style of the patient (…) so [that the decision is affected by your perspective] (…) is not actually incorporated into the models that decision aids are developed from (Physician).

Another strategy that was suggested to take SDM beyond the confines of the consulting room was to involve an independent party, considered by one respondent to be especially important given today's highly specialized healthcare system.

Forty years ago, doctors knew everything. Nowadays, the research is catching up on us, things are changing very rapidly, and health care is much more differentiated into all kinds of sub‐specialisms (…) [We need generalist physicians] that act as coaches for patients, who can explain the information, weigh the pros and cons together with the patient. Shared decision‐making is an important part of that. There is no one truth or a clear good or bad anymore (Physician)

Involving an independent party was also central to the “time out conversations” that have been implemented in oncology.

After patients have been diagnosed with cancer (…) they first talk to their GP about what is going on. What is the proposed treatment? How are you doing? Do you want to be treated in that hospital? (…) [Alternatively] do you want to go to another hospital to get a second opinion? (…) These kind of subjects are discussed in a (…) time‐out conversation with the GP [acting as an independent party] (Oncologist)

Experiences with the breakout conversations in oncology showed that GPs expressed a need for instructions from the oncologist in order to fulfil their role effectively. Thus, roles and collaborations between different healthcare providers are reconfigured to accommodate an understanding of (S)DM as an interprofessional and transmural process. To conclude, this section on system‐level barriers and strategies shows how decision‐making is conceptualized more as a multi‐dyadic process that is distributed across several contact moments between medical and non‐medical actors.

5. DISCUSSION

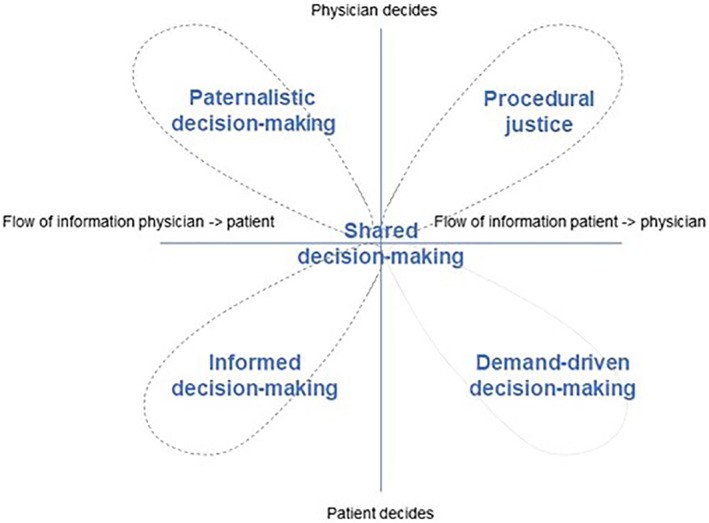

This study examined how healthcare professionals give meaning to the concept of SDM in everyday practice. The findings describe three varieties of SDM: (a) SDM as a negative right, (b) Informed decision‐making and (c) Tailored partnership. This variety of decision‐making styles resonates with the doctor‐patient partnership framework developed by Charles et al20 that distinguishes different types of partnership: paternalistic decision‐making, SDM and informed decision‐making. Nevertheless, the authors note that physicians will mostly opt for “intermediate approaches” to patient‐doctor partnership in order to accommodate to the unique particulars and patient needs—thus offering a flexible decision‐making continuum. Indeed, our findings show that many healthcare professionals position themselves somewhere around the centre of SDM, as depicted in Figure 1 below.

FIGURE 1.

A dynamic decision matrix

Previous studies perpetuate SDM as a normative model that encourages judgements about differences between current practice and “desired” practice.27 We underline a more nuanced understanding of SDM that builds on an increased awareness of one's position on and movement across the dimensions of the decision‐making framework—building on the need for a “subtler vocabulary.”28 For example, constraints imposed by CPGs were perceived by some as narrowing the manoeuvring space to paternalistic decision‐making. Meanwhile, others proposed a nuanced shift from paternalistic decision‐making to procedural justice to foster a bilateral flow of information and maintain patient's sense of control even when there are no options to choose from. We summarized these approaches in a set of strategies that offer different perspectives on how manoeuvring space can be occupied and expanded and resonates with the notion of SDM as a “graded” framework (see also: Berg et al28).

Berg et al28 note that for every decision patient autonomy needs to be balanced against other ethical principles. This continuous balancing act shows how SDM is a process that may take on different shapes over the course of a treatment trajectory, rather than a one‐off interaction. Our findings showed that individual and systemic barriers impose constraints on this ethical balancing act, limiting the manoeuvring space for SDM. As a result, sense making in large part revolved around exploring manoeuvring spaces and trying to adapt accordingly. The fifth barrier, for example, showed how time constraints are imposed by a reimbursement system of fixed 10‐minute consultations that render individual‐focused strategies insufficient. Rather, strategies emphasized how decision‐making should be conceptualized as a multi‐dyadic process that is distributed across several contact moments with medical and non‐medical actors. This shift toward “distributed decision‐making”2927 illustrates that our understanding of SDM affects our assessment of its feasibility by offering new avenues for making it workable in contemporary medicine.

More research on system‐level interventions is needed to expand the borders that surround the doctor‐patient interaction29 and manoeuvring space for SDM, including the adaptation of CPGs to facilitate SDM.26, 29

5.1. Limitations

A limitation of this study is the predominant representation of healthcare professionals, mostly hospital‐based physicians and medical residents. We acknowledge that certain topics require further study to include the perspectives of other relevant actors. One such topic is the operationalization of distributed decision‐making. Furthermore, we decided not to touch upon the contested distinction between patients' unwillingness and inability to become active agents in decision‐making, because we feel these issues have been discussed more extensively in other papers.22, 30

6. CONCLUSION

This study explores how healthcare professionals make sense of SDM and accompanying implementation issues. Previous studies identified lack of a shared, coherent understanding of SDM as the most important barrier that hinders moving from current to desired practice, thus framing SDM as a normative model. This study found different varieties of how SDM is defined and practiced. Furthermore, we identified five barriers that limit the manoeuvring space for practicing SDM. Building on this, we framed the diverse ways in which healthcare professionals define and practice SDM not as a lack of consensus, but rather a response to the limitations posed by barriers that contest the feasibility of a uniform, normative SDM model. There is a need for a more nuanced understanding of SDM as a “graded” framework that allows for flexibility in the decision‐making style to accommodate patient's unique preferences and needs. An understanding of SDM as a process of multi‐dyadic interactions that spatially exceed the consulting room offers new avenues to make SDM workable in contemporary medicine.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study protocol was submitted to the board of directors of the hospital who, advised by the Advisory Committee on execution of scientific research, granted ethical approval on 31st of March 2015 for conducting interviews with patients. The interviews with healthcare professionals were exempt from ethical approval. All study participants signed informed consent forms prior to the interviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors appreciate assistance in data collection and analysis from Aniek Akerboom, Esmee Wardenaar, Hanneke Houben, Jasper Wind, Julie Swillens, Tuğba Aydın, Maaike Vermunt, and Reinier van Nieuw Amerongen. We also greatly appreciate the time spent by healthcare professionals and patients to participate in this study.

Moleman M, Regeer BJ, Schuitmaker‐Warnaar TJ. Shared decision‐making and the nuances of clinical work: Concepts, barriers and opportunities for a dynamic model. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27:926–934. 10.1111/jep.13507

Endnotes

Although this act of integrating and weighing cannot necessarily be explicated in SDM models in order to guide practice, this “how to” is currently also not addressed in medical education, as courses on EBM and SDM so far have remained separate. (See References 3).

Oncology, neurology and gastroenterology.

Decisions for which SDM is advocated as the preferred decision‐making style.

The contested distinction between patient's willingness and ability to participate in decision‐making is discussed extensively in Reference 22.

CPGs could signal moments when clinicians' are advised to elicit patient preferences. Furthermore, CPGs could support SDM by offering a list of probing questions to assess for example whether a therapy would fit into the patient's life. (See Reference 26).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The anonymizsed data and materials of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hamann J, Leucht S, Kissling W. Shared decision making in psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:403‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barratt A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences into health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):407‐412. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Del Mar C. The connection between evidence‐based medicine and shared decision making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295‐1296. 10.1001/jama.2014.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361‐1367. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, et al. A three‐talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017;359:j4891. 10.1136/bmj.j4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nijhuis FAP, Faber MJ, Post B, Bloem BR. Samen beslissen: dilemma's in de praktijk |Vervolgtherapie bij gevorde ziekte van Parkinson als voorbeeld. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2017;161:D1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friesen‐Storms JHHM, Bours GJJW, van der Weijden T, Beurskens AJHM. Shared decision making in chronic care in the context of evidence based practice in nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):393‐402. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1172‐1179. 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd A, Joseph‐Williams N, Edwards A, Rix A, Elwyn G. Patchy “coherence”: using normalization process theory to evaluate a multi‐faceted shared decision making implementation program (MAGIC). Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):102. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elwyn G, Légaré F, Van Der WT, Edwards A, May C. Arduous implementation: does the normalisation process model explain why it's so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice. Implement Sci. 2008;3(1):57. 10.1186/1748-5908-3-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph‐Williams N, Lloyd A, Edwards A, et al. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ. 2017;j1744:357. 10.1136/bmj.j1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.May C, Rapley T, Moreira T, Finch T, Heaven B. Technogovernance: evidence, subjectivity, and the clinical encounter in primary care medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):1022‐1030. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevenson FA. The strategies used by general practitioners when providing information about medicines. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43:97‐104. 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00154-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas A, Kuper A, Chin‐Yee B, Park M. What is “shared” in shared decision‐making? Philosophical perspectives, epistemic justice, and implications for health professions education. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:409‐418. 10.1111/jep.13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535‐554. 10.1177/0038038509103208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Politi MC, Studts JL, Hayslip JW. Shared decision making in oncology practice: what do oncologists need to know? Oncologist. 2012;17(1):91‐100. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goss C, Moretti F, Mazzi MA, Del Piccolo L, Rimondini M, Zimmermann C. Involving patients in decisions during psychiatric consultations. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(5):416‐421. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slade M. Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):146‐153. 10.1002/wps.20412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azevedo MA, Dall'Agnol D. An agency model of consent and the standards of disclosure in health care: knowing‐how to reach respectful shared decisions among real persons. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(2):389‐396. 10.1111/jep.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by Partnership in Making Decisions about treatment? Medizinhist J. 1999;319(7212):780‐782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonelli MR, Sullivan MD. Person‐centred shared decision‐making. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25(6):1057‐1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph‐Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient‐reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291‐309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuitmaker TJ. Identifying and unravelling persistent problems. Technol Forecast Soc Change . 2012;79(6):1021–1031. 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leventhal GS. What should be done with equity theory?Social Exchange. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1980:27‐55. 10.1007/978-1-4613-3087-5_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyler TR. The psychology of procedural justice: a test of the group‐value model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(5):830‐838. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montori VM, Brito JP, Murad MH. The optimal practice of evidence‐based medicine: incorporating patient preferences in practice guidelines. JAMA. 2013;310(23):2503‐2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapley T. Distributed decision making: the anatomy of decisions‐in‐action. Sociol Heal Illn. 2008;30(3):429‐444. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berg H, Bjornestad J, Våpenstad EV, Davidson L, Binder PE. Therapist self‐disclosure and the problem of shared‐decision making. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(2):397‐402. 10.1111/jep.13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maassen EF, Schrevel SJC, Dedding CWM, Broerse JEW, Regeer BJ. Comparing patients’ perspectives of “good care” in Dutch outpatient psychiatric services with academic perspectives of patient‐centred care. Journal of Mental Health . 2017;26(1):84–94. 10.3109/09638237.2016.1167848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Der Weijden T, Pieterse AH, Koelewijn‐Van Loon MS, et al. How can clinical practice guidelines be adapted to facilitate shared decision making? A qualitative key‐informant study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):855‐863. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumenthal‐Barby JS. That's the doctor's job': overcoming patient reluctance to be involved in medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):14‐17. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymizsed data and materials of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.