Abstract

Objective

The study aimed to better understand the complexities of parental responses to coming out in the narratives from Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, Pansexual, or Two‐Spirited (LGBQ+) individuals, and to examine whether those from recent cohorts experience a different parental response than those in older cohorts.

Background

Sexual minorities come out at younger ages today than in past decades, and coming out to parents is a major part of the identification process.

Method

Interview excerpts of 155 US lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, pansexual, or two‐spirited (LGBQ+) respondents were analyzed with a qualitative thematic analysis and with basic quantitative methods. The sample consisted of 61 interviewees in a young cohort (ages 18–25), 65 in a middle cohort (ages 35–42), and 29 in an older cohort (ages 52–59), in six ethnic/racial groups.

Results

Themes based on LGBQ+ people's accounts indicated that parental responses varied with the degree of their a priori knowledge of respondents' sexual identities (ranging from suspicion or certainty to surprise). Parental appraisal was either lacking, negative, mixed, or positive with accompanying silent, invalidating, ambivalent, and validating responses, respectively. Validating responses from parents were more often found in the youngest cohort, but invalidating responses were frequent across all cohorts. LGBQ+ people in the oldest cohort were more inclined to accept their parents being noncommunicative about sexuality in general and also about sexual diversity.

Conclusion

It is too early to state that coming out to parents has become easier. Harmony in the parent–child relationship after coming out and open communication about sexual identities is regarded as desirable and yet it remains elusive for many LGBQ+ people.

Keywords: cohort, family conflict, family diversity, family relations, sexuality

Coming out, the process of identifying and disclosing one's sexual minority attraction to others, and potentially identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, or another nonheterosexual identification (LGBQ+), has interested family researchers, mental health clinicians, and researchers since the 1970s (cf. Cass, 1979; Coleman, 1982). Coming out to parents is a major part of the identification process in sexual minority identity development. Parents fulfill a crucial role in the psychosocial well‐being of their children; their role is particularly salient in adolescence, the period characterized by development of both sexuality and identity, but continues into adulthood and throughout life (Bray & Stanton, 2009).

Given that relationships with parents are important for psychosocial well‐being across the lifespan (Bray & Stanton, 2009), and given the sexual prejudice that continues to characterize contemporary US society, it is perhaps unsurprising that sexual minorities often fear or anticipate rejection from their parents and worry about their response (Charbonnier & Graziani, 2016). Research conducted from the 1980s to the early 2000s indicated that nonaffirming parental reactions to their children's coming out are common and that the period around disclosure to parents often taxes the parent–child relationship (Patterson, 2000; Savin‐Williams & Dubé, 1998; Willoughby et al., 2008). Parental rejection generally has a negative impact on sexual minority youths' psychosocial adjustment (D'Augelli, 2003; Ryan et al., 2010), because young people's self‐perceptions are influenced by how they believe their parents evaluate and view them (Rohner, 2004). In contrast, research shows that when LGBQ+ youth have a positive coming out experience with their parents, it helps them to feel whole and experience a sense of coherence (Perrin‐Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015). By the time that LGBQ+ youth come out to their parents, they have been aware of their same‐sex attraction for 3 years on average, so parental acceptance can provide a sense of safety, confidence, and even liberation (Perrin‐Wallqvist & Lindblom, 2015). Parental validation of their children's sexual minority identity predicts greater self‐acceptance, higher self‐esteem, and is associated with less depression, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation and behaviors in their children (Ryan et al., 2010). Nevertheless, parental responses to their child's disclosure are currently not fully understood in all their nuances and subtleties (Reczek, 2016).

Parental Responses to Coming‐out: Differences by Age Cohort?

Discourses around LGBQ+ people have changed over the past decade(s) (Dunlap, 2016; Witeck, 2014). LGQB+ youth who grow up in Western societies at present are embedded in a socio‐cultural context that stresses equality more so than before and that features increasing societal and judicial support for sexual minorities (Witeck, 2014). For example, inclusive approaches have been successfully introduced to LGBQ+ people regarding their equal rights to legal marriage in the United States and over two dozen other nations, as well as the right to serve in the military in many nations. However, older cohorts of LGBQ+ people (born in the 1950s and 1960s) in the United States and western Europe grew up at the time when “homosexuality” was considered a psychiatric disorder. This was also the time when gay pride discourses emerged among LGBQ+ communities, following the first gay pride events. A different cohort of LGB+ people born in the 1970s and 1980s came of age at a time when the HIV/AIDS epidemic peaked in the United States and Europe but adequate AIDS treatments became available. Thus, despite facing more stigma due to fear of AIDS, there was also greater political awareness and access to LGBQ+ community for LGBQ+ people.

Due to these socio‐cultural changes, knowledge and acceptance of LGBQ+ issues in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, coming out processes to parents are likely to be different for older cohorts of LGBQ+ people than middle or younger cohorts. The present study had two aims. We explored the range of responses parents had to their children's disclosure, including potential nuances by using retrospective recollections of LGBQ+ people of various ethnicities/races. Additionally, we aimed to identify potential variation across age cohorts.

A small body of literature that has explicitly examined and compared different age cohorts of LGBQ+ individuals suggests that contemporary sexual minorities come out both at younger ages (Dunlap, 2016) and in greater numbers (Dunlap, 2016; Grov et al., 2006; Savin‐Williams, 1998) than in the 1980s or 1990s. In the United States, Floyd and Bakeman (2006) explored possible maturational (coming out at a young vs. older age) or historical (coming out in earlier sociohistorical periods) differences, and found some evidence for both models. Respondents who came out when young were still living at home and under parental control, whereas those who came out later had more social and financial freedom. These age‐related differences were found both among older and younger respondents, indicating a variety of coming out trajectories. Similarly, Grov et al. (2006) surveyed LGB participants of five age cohorts (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55+) in New York City and Los Angeles and found evidence that the youngest cohort had come out at younger ages.

Grierson and Smith (2005) interviewed 32 gay men living in Melbourne, Australia, consisting of 11 who were born between 1953 and 1962 (“pre‐AIDS”), 11 born between 1963 and 1969 (“peri‐AIDS”), and 10 born after 1969 (“post‐AIDS”). The oldest group reported coming out to parents as tense and emotionally charged, and of “working up the courage, of contemplating possible consequences” (p. 59). For this cohort, coming out usually changed their relationship with their parents, often in positive ways. The youngest group came out at a younger age, expected a more positive response from their parents, and seemed more matter‐of‐fact in talking about the experience than were the older men.

Besides the few cohort studies on coming out, a different way of evaluating how parental reactions may have changed over the past decades is to compare findings of coming out to parents by LGBQ+ people in studies published from the 1970s until the 2010s. Studies of LGBQ+ participants who came out to parents in the late 1970s (DeVine, 1984; Lewis, 1984) demonstrate that disclosure was followed by parental avoidance (denial, or a refusal to acknowledge, that their child is LGB), as well as conflict. Results based on LGBQ+ samples in the 1990s and the start of the millennium also emphasized that the majority of parents responded to their children's disclosure negatively at first, expressing emotions such as anger, shock, denial, embarrassment, or sadness but also suggest that improvement occurred when parents were willing to change their (heteronormative) beliefs (D'Augelli et al., 1998; Goldfried & Goldfried, 2001; Savin‐Williams & Ream, 2003). However, research has indicated that the expression of positive and negative reactions, and changes toward acceptance among parents, did not always follow a linear progression. For example, the majority (85%) of the 60 participants in a study by Reczek (2016), who came out in the 1990s, narrated ambivalent reactions from parents. Examples included parental acceptance (e.g., being friendly toward same‐sex partners) combined with overt or covert rejection (e.g., not including the same‐sex partner in a letter about an official family occasion). Furthermore, unlike respondents who came out in the 1970s, a new theme among youth coming out in the 1990s was that some parents suspected and asked their children if they were LGB (Savin‐Williams, 1998).

Studies from the past decade support the idea that invalidating responses remain common, yet parental responses are more varied than merely rejection versus acceptance. For example, D'Amico et al. (2015) distinguished three core dimensions in parental responses: Parental Support, Parental Struggles, and Parental Attempts to Change Their Child's Sexual Orientation. Roe (2017) found that some parents provided their children with mixed messages, where the parents would express affection but also make hurtful remarks about their children's LGB identity. Rosario et al. (2009) suggested a “neutral” category, referring to “indifferent parents,” in addition to rejection and acceptance. Although the neutral and accepting responses outnumbered the negative responses, rejection continued to be common.

Considering the wealth of literature about coming out to parents, as well as the increasing evidence that parental responses go beyond rejection versus validation, it is analytically important to work with a model that can illuminate the multifaceted and complex nature of this phenomenon. Chrisler (2017) recently presented a theoretical model of multiple components of coming out responses by parents drawing from empirical literature in a narrative tradition (based on over 20 studies). The model views coming out as a multidimensional process and is thus very suitable for examining a broad variety of parental appraisals, their rationale, and unfolding coping behavior by parents following disclosure. Chrisler's components consist of the following: (a) The degree to which parents have a prior notion about their child's feelings (i.e., some parents have suspicions, which may initiate uncertainty reduction activities, and other parents are unaware); (b) at some point it is (directly or indirectly) confirmed or disclosed to parents that their child is attracted to the same sex and/ or has an LGBQ+ identity; (c) disclosure is accompanied by parental appraisal, where parents inscribe meaning to this new information, and convey whether it conflicts or resonates with their beliefs and values; (d) appraisal is influenced by parental ability to identify coping strategies; (e) appraisal is often followed by, or coincides with, a response that includes an evaluation; (f) many parents when they get confirmation of their child's same‐sex attraction, and as a way to reduce or deal with their stress, apply coping strategies (e.g., avoidant and approach coping styles), a process that may be followed by re‐appraisal of their child's disclosure. Furthermore, (g) all components are influenced by contextual factors, including parent and family relationships, as well as cultural or societal beliefs and values.

Study Goals

The evolving body of research that maps the range of parental responses is important for thinking beyond a rejection‐acceptance dichotomy or continuum, but more research is needed to document and understand these complex and varied responses and digest them analytically This is of particular importance given the profound societal changes in LGBQ+ acceptance in the past decades. Therefore, our research questions are: (a) What range of parental responses to coming out emerge among narrative interviews with LGBQ+ people of various ethnicities in the United States in three age cohorts? (b) To what extent are there thematic differences between the three age cohorts in narratives about parental responses to coming out? and (c) To what extent do narrative themes analytically fit within Chrisler's (2017) framework of parental reactions to coming out? We were sensitized by literature that suggests that positive or a somewhat more “neutral” content (Rosario et al., 2009) would be more often found in the younger cohort, whereas negative reactions would be more prevalent in the middle and older cohorts (Savin‐Williams & Cohen, 2015).

Method

Study Design

Data come from the Generations Study, a large‐scale, multimethod project that included qualitative interviews. The overall aim of the Generations Study is to explore cohort differences in sexual identity, minority stress and resilience, and access to healthcare and health outcomes for LGBQ+ adults in the United States. The study focuses on three cohorts of US LGB people (http://www.generations‐study.com). The older age group (ages 52–59) in our study grew up as the first post‐Stonewall cohort, during an era when homosexuality was perceived to be a mental health disorder and sodomy was illegal in many US states. It was also this age group of LGBQ+ people who first started making endeavors to cultivate pride within their communities, so we refer to this group as the Pride cohort. The middle age group (ages 34–41) came of age in the United States at a time when the HIV/AIDS epidemic peaked in the United States and political awareness increased, sodomy laws were shown to be unconstitutional, and the federal “don't ask, don't tell” policy in the US military was overturned. We refer to this cohort as the Visibility cohort. Finally, we refer to the youngest cohort (ages 18–25), as the Equality cohort, because they came of age at a time when discourses around LGBQ+ people changed to those stressing equality, and the overall attitude among the US population had become more accepting of LGBQ+ rights (Witeck, 2014).

Instrument

For the Generations Study, interviews were conducted using a narrative approach (e.g., Frost et al., 2014), in a semi‐structured protocol. The main topics of the instrument were key events and trajectories in participants' life stories, same‐sex awareness (including disclosure to family and friends), sexual identity development, minority stress experiences, internalized homophobia, and healthcare experiences. For the analyses in our study we drew from those sections of the interview that focused on same‐sex attraction awareness and potential and/or partial disclosure to significant others. A key question was: “Tell me about how you came to identify yourself with this sexual identity label and your process of telling others about your identity?” (followed by a probe about coming out to parents).

Participants, Recruitment, and Procedure

Participants were recruited from within 80 miles of four geographic regions of the United States: New York City Metro area; San Francisco Bay Area; Tucson, Arizona; and Austin, Texas. Participants were eligible for the study if they resided in the United States when they were aged 6–13 (to assure these individuals came of age in the social contexts that are the subject of this investigation); were proficient in English; and had completed the sixth grade of school or higher. Quota sampling ensured equal representation of participants across cohorts.

To meet these sampling aims, the study used an adapted targeted nonprobability sampling strategy. A list was made of key venues visited by sexual minority individuals in each of the four sites (e.g., stores, restaurants, churches/synagogues, parks, bars, etc.). In order to find interviewees who might not otherwise attend these venues, advertisements were placed in local social media. Trained recruiters sought participants from these venues, and gave candidates study information that included a website and a toll‐free number where screening for eligibility took place. Coordinators checked and ensured that no venue was disproportionately represented in the sample. Interviews were held at university offices or other private locations suggested by participants. Participants were given $75 for their participation. Interviews were collected between April 2015 and April 2016, and lasted 2–3 hours. The study had Institutional Review Board approval.

The total number of interviewees was 191; however, for this study 35 respondents (n = 12 equality cohort, n = 5 visibility cohort, n = 18 pride cohort) had to be excluded because they had either not come out to their parents, they had come out but the parental response was not discussed, or it was unclear whether they had come out to their parents. The sample for this study thus consisted of 61 interviewees in the equality cohort, 65 in the visibility cohort, and 29 in the pride cohort (n = 155). About 65% identified as gay or lesbian, 20% identified as bisexual, and 15% as queer, pansexual, or two‐spirit. Transgender participants were included in a separate US Transgender Population Health Survey. About 40%–45% of participants identified as male, a similar percentage as female, and 10% as gender queer. Race/ethnicity was reported as White (n = 38), African American (n = 28), Latino/Hispanic (n = 31), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 23), American Indian (n = 15) and Bi‐ or Multiracial (n = 21).

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and stored in Dedoose 2016 qualitative software. The relevant transcript excerpts (i.e., those related to coming out to parents) were retrieved by first studying answers of participants to the probe about coming out to parents (asked by interviewers in approximately 90% of all cases). We combined this with a computer‐aided search of the entire transcript, using the search words coming out, come out, (came out), disclose, family, parent(s), mother, mum, mom, father, and dad. Relevant excerpts were stored in Excel (categorized by interviewee), and consisted of 250–1,200 words, with an average of 335 words per interviewee. Given the size of our sample, and our interest in differences in the coming out experience across socio‐historical cohorts, we tested for the significance of patterns across cohorts by treating data that could be counted (i.e., the presence versus absence of coded themes) quantitatively and using chi‐square tests. These analyses are presented prior to the qualitative investigation in each result section. Separately, we performed a qualitative thematic analysis (Hiles & Čermák, 2008) of all excerpts, which was conducted based on a constant and systematic comparison (Boeije, 2002). The thematic analysis began with open coding; coding was conducted by a team of four researchers (diverse in terms of gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity). The first author coded narratives of coming out responses from parents and grouped responses into categories. Then the second, third, and fourth authors compared the raw data to the initial coding by the first author and commented on, revised, or supplemented the codes. The first author refined coding accordingly and discussed codes until consensus was reached in cases of disagreement. These four authors made suggestions for interpretation of the coding (Hiles & Čermák, 2008) that led to theme identification.

The initial codes developed by the first author were “Various levels of shock versus knowledge,” “Rejection,” “Acceptance,” and “No explicit rejection but no acceptance” responses. However, through discussions, the authors decided that “Rejection” and “Acception” were too binary based on what some participants reported. These observations led to adjustments and eventually arrival at a final set of codes: “Invalidating response” and “Validating response” were recognizable, but “No explicit rejection but no acceptance” proved not to be precise enough and we reworked this into codes that reflected the behavior or type of response beyond positive/negative responses: “Silence” and “Mixed positive and negative responses.” These codes provided the basis for our narrative themes. In a second stage, the authors recognized the saliency of Chrisler's (2017) theoretical model of components in coming out to parents in the narrative themes that emerged from our analytic process. As such, the Chrisler model provided a way to re‐organize the findings. This also led to the addition of the theme “Coping behavior” to our analysis. Initially, we attempted coding for “Same‐gender parent versus other‐gender parent response,” but there were quite a few cases where only one parent's response was reported, and therefore this code was left out of our further analyses. Race and gender were not analyzed systematically and will thus only be reported when a salient difference was observed regarding these markers. Furthermore, the data did not allow for a systematic analysis regarding the age when respondents came out. For all thematic findings, we provide quotes as sample pieces of evidence and frequencies to indicate saliency and prominence of each theme. The frequencies reported are not mutually exclusive because multiple characteristics were sometimes found in coming out incidents and some participants reported more than one incident that differed in characteristics.

Results

Narrative Themes in Relation to Coming out to Parents

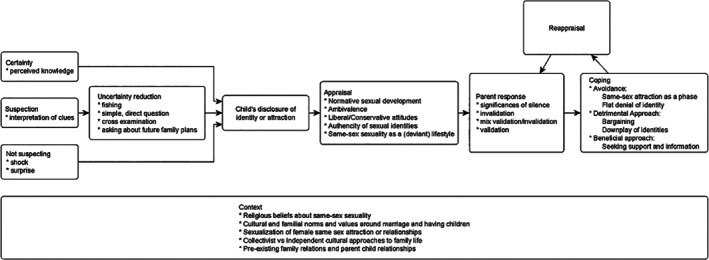

A first set of themes demonstrated that, according to participants, parental responses varied with the degree of their a priori knowledge about respondents' sexual identity. These responses ranged from suspicion to surprise, which largely match the first components in Chrisler's model; we also identified “certainty.” Moreover, parental appraisal (a core component in Chrisler's model) was visible in our data, yet we were also able to expand this component into lacking, negative, mixed, or positive appraisals with accompanying silent, invalidating, ambivalent, and validating responses. Unlike Chrisler (2017) we relied on descriptions of parents' responses as indications of their appraisals. Furthermore, similar to Chrisler (2017), we also identified parental coping behavior on the basis of interviews with LGBQ+ respondents that reflected avoidance (e.g., denial or negation) but also identified approach coping styles (e.g., seeking support). Findings are elaborated accordingly and summarized in Figure 1. Figure 1 is an adapted and supplemented version of Chrisler's model, based on our empirical findings.

Figure 1.

A theoretical‐empirical framework of parental responses when a child comes out with a same‐sex attraction, in three cohorts in the United States (adapted from Chrisler, 2017).

LGBQ+ Children's Accounts of the Degree of Parental (Un)Certainty and how Parents Addressed this (Un)Certainty

Parental Suspicion and Parental Certainty

Many respondents (n = 43) stated that their parents (mostly their mother) had suspected or even said they were certain before their child came out. We did not find significant cohort differences in the frequency of suspicion or certainty, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 1.07, ns (see Table 1). A Black woman in the visibility cohort described suspicion in her mother: “she said, ‘I suspected it’ or ‘the family suspected it,’” or as a Latino man in the pride cohort stated: “I told her (mother) if she really thought it was that big of a surprise, and she said no.”

Table 1.

Frequency of Key Themes by Age Cohort in a Sample of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Other Sexual Minority (LGBQ+) Adults in the USA (n = 155)

| Cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equality (18–25 years); n = 61 | Visibility (32–41 years); n = 65 | Pride (52–59 years); n = 29 | |||||

| Themes | n | % | n | % | n | % | Chi‐square |

| Knowledge | |||||||

| Yes | 19 | 31% | 18 | 28% | 6 | 21% | 1.07 |

| No | 42 | 69% | 47 | 72% | 23 | 79% | |

| Uncertainty reduction | |||||||

| Yes | 9 | 15% | 9 | 14% | 4 | 14% | 0.03 |

| No | 52 | 85% | 56 | 86% | 25 | 86% | |

| Shock | |||||||

| Yes | 9 | 15% | 13 | 20% | 4 | 14% | 9.89* |

| No | 52 | 85% | 52 | 80% | 25 | 86% | |

| Invalidating | |||||||

| Yes | 28 | 46% | 29 | 45% | 12 | 41% | 21.96* |

| No | 33 | 54% | 36 | 55% | 17 | 59% | |

| Silence | |||||||

| Yes | 11 | 18% | 24 | 37% | 7 | 24% | 5.78 |

| No | 50 | 82% | 41 | 63% | 22 | 76% | |

| Mixed | |||||||

| Yes | 15 | 25% | 25 | 38% | 7 | 24% | 4.22 |

| No | 46 | 75% | 40 | 62% | 22 | 76% | |

| Validating | |||||||

| Yes | 37 | 61% | 25 | 38% | 15 | 52% | 45.01* |

| No | 24 | 39% | 40 | 62% | 14 | 48% | |

| Avoidant coping | |||||||

| Yes | 10 | 16% | 14 | 22% | 1 | 3% | 13.70* |

| No | 51 | 84% | 51 | 12% | 28 | 24% | |

| Approach copinga | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 11% | 8 | 12% | 7 | 24% | 16.96* |

| No | 54 | 89% | 57 | 86% | 22 | 76% | |

Note: Chi‐square used to examine differences in frequency across age cohorts.

Only negative approach coping styles were included in the calculations, due to low number of cases retrieved across all cohorts for positive approach coping.

Significant at p < .05.

Furthermore, we identified a new subtheme that extends the first component of Chrisler's (2017) framework. Our data showed many examples of respondents who said their parents had been certain and convinced (beyond suspicion) even before they came out. As a White woman from the equality cohort stated, “They (parents) were like ‘We knew’”. In most cases, respondents described this pattern of perceived knowledge for their mothers: when we asked respondents to share the reasons they thought their mother knew, they reported that “a mother always knows her child” (quote from a Multiracial man from the pride cohort). Other respondents said their parents had prior knowledge based on respondents' gender expression or gender nonconforming friends, the intensity of their same‐sex friendships, or their admiration for a specific (same‐sex) person.

Although the frequency of suspicion or certainty did not differ much across age cohorts, qualitative analyses suggested that how respondents reacted when parents expressed their perceived knowledge or suspicion may vary by cohort. This will be discussed next.

Reports of Parents Asking Directly About Sexual Orientation to Reduce Uncertainty Versus a Lack of Desired Communication

A substantial portion of respondents said their parents had asked directly when they suspected (n = 22), with no variation in frequency among the three cohorts, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 0.03, ns (see Table 1). Respondents said their parents asked them about the gender of their romantic attraction, or explicitly inquired about their sexual identity. For instance, a Multiracial man from the equality cohort illustrated: “He (stepfather) said, ‘can I ask you a question?’ outta nowhere.(…) He said, ‘Are you gay?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’” A White woman from the pride cohort, heard a different tone from her parents: “I had my mom over for dinner one night… She said, ‘Are you and Sandy more than just friends?’ …I drummed up every amount of courage I had and burst into tears…and said yes. My mom was mad.” Some respondents indicated that their parents were “fishing” or in exceptional cases they even felt they were worn down by what resembled a “cross‐examination.” As can be seen from the examples, suspicion about their child's sexual identity was followed by a variety of parental evaluations. However, when direct asking felt like a cross examination, this was always followed by a negative parental response.

In other cases, however, respondents would have appreciated parental “uncertainty reduction strategies” (i.e., having a conversation with them). Some respondents also asked their mothers why they had known or suspected but had never said anything. A few mothers replied they did not want to upset their child by asking about their sexuality if it was not true, as a Latino man from the visible cohort quoted his mother: “What if you weren't and I just assumed you were, and then I would've—you would have an identity crisis?” Some respondents were frustrated with their parents and attributed their (past) sexual identity development challenges to this lack of parental engagement. For example, a Black woman from the visibility cohort exclaimed:

‘Why the hell didn't you guys tell me so that I would know what was happening?’ I was just this person, I was completely asexual—it would have been nice for them to tell me that that's what I was.

Some respondents felt they had missed out on an opportunity for support for their well‐being, as a Latino man from the visibility cohort illustrated: “Mom, it would have made my life so much easier if you'd just said, ‘I know you're gay and you can be who you are and be happy.’” Or as an American Indian woman from the equality cohort phrased it: You knew all this time, and made me go through all this shit to tell you?” Respondents in the equality and visibility cohorts had seemed frustrated over unnecessary suffering when parents said they had known but never brought it up, whereas no respondents in the pride cohort commented on parents knowing or suspecting but not telling.

Nonsuspecting Parents: Shock and Surprise

Several participants (n = 26) had parents who had not suspected at all and described reactions of shock or surprise when they disclosed their sexual identity. Participants in the visibility cohort reported parental shock and surprise significantly more often than those from either the equality or the pride cohort, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 9.89, p < .05 (see Table 1). Qualitatively, however, shock or surprised seemed very comparable across cohorts. An example of shock comes from a Latina/White woman from the visibility cohort who described her mother's response:

I said: ‘I'm gay.’ I was holding her hand and she pulled her hand away and … her face just fell. She went from looking concerned and a little worried to just shocked. She just looked stunned (…) ‘I don't know what to say.’ I said ‘Do you wanna ask me anything? Do you want me to leave?’ She said, ‘No. I don't know (…)’ She moved. She physically had moved away from me.

Respondents reported shocked responses from their parents mostly in tandem with a nonaffirmative reaction, including negative emotions such as crying, screaming, and outburst of anger. Nevertheless, some exceptions existed, as the narrative of an Asian woman from the equality cohort showed:

She took a deep breath, and kept asking if I was sure, but I think she just asked that cuz she didn't know what to say. She didn't have a pamphlet telling her how to respond to a child that just came out to you, and so she stated that… She sat me next to her and told me that it's okay.

Appraisal of Same‐Sex Sexuality: Silence, Invalidation, Mixed Responses, and Validation

Appraisals of Same‐sex Sexuality as a Taboo, Followed by Silent Responses from Parents

Whether parents suspected or not, they all engaged in appraisal of the same‐sex sexuality of their children when they found out, which then went hand in hand with an accompanying response. Across cohorts, many respondents reported that their parents reacted with silence (n = 42), χ 2(6, n = 155 = 5.78, ns (see Table 1), including parents who did not appear to suspect that their child was LGBQ+. Silence could mean many things, including that sexuality was a “forbidden” topic; however, silence could also be indicative of general difficulties families faced vocalizing emotions. Silence could also mean a covert negative response or a covert positive response. Finally, silence could be a marker of the unknown. First, some respondents indicated that sexuality (regardless whether heterosexual or nonheterosexual) was appraised as a “taboo topic” in their family before, and also after, they came out. As a Latino man from the equality cohort explained: “it's always just been one of those things swept under the rug… if something about that came on TV, my mom would turn it off.” Another illustration of the taboo of sexuality came from a Multiracial woman from the pride cohort: “I knew they wouldn't understand, so I just didn't talk about it with them. My parents never talked about sex anyway. That was something that wasn't a polite conversation.” In these examples, parents indicated discomfort regarding same‐sex attraction, and it was difficult for children to discuss their sexual identity with them. In some cases coming out as LGB was associated with such taboo that it led to a breakdown in communication between respondents and parents. For most respondents, this breakdown was limited to the topic of same‐sex attraction, but in a few cases the silence was general and lasted several months to over two decades (at time of interview).

Next, multiple respondents perceived that a lack of communication from their parents upon their coming out went hand‐in‐hand with a lack of ability in their families to verbalize emotions in general. As a White man from the visibility cohort illustrated:

It became really obvious that we weren't ever talking about any of it (sexuality). But the isolation and the suppression of emotions is still running rampant in my family. Nobody knows how to talk about feelings at all.

This respondent understands silence about his sexuality as embedded in a family that lacks abilities for communication about feelings. Some respondents referred to their parents' culture, age or traditions as playing a big role in sexuality (and thus, also same‐sex sexuality) as a taboo or as a “no go area,” because it involved talking about emotions.

Those parents who were described as silent often initially refrained from giving any explicit evaluation later on as well. As a White male from the visibility cohort pointed out:

The only times that we have acknowledged in conversation or communication that I'm gay was when I came out… My mother said over and over again, ‘I just don't know what to do with this information’ and then that was the absolute end of publically acknowledging or communicating in the family that I am gay.

When coming out was the reason for a full breakdown in communication between respondents and their parents, the meaning of silence was negative and parents were perceived as rejecting. Nevertheless, some respondents felt that parental inability to communicate about their sexual identity was not necessarily a rejection. Parental silence was then a marker of the unknown. Those respondents noted difficulty reading their father's mind in particular (it was common that mothers informed fathers, that is, an indirect coming out), as a White woman from the visibility cohort said: “He (the father) actually has not even mentioned it to me. I've been around him by myself. I've been around him with her (respondent's girlfriend). Even now he knows, but I don't know how he feels about it.” In these cases, silence from parents tapped into insecurity about parental approval. Another variation observed in some cases, however, was parental silence that was perceived as an unspoken form of acceptance, as a Multiracial woman from the visibility cohort illustrated: “I've never been shown any discontent from my family. My dad, who found out through them [mother and sisters], I never had to talk with him but it was just understood.”

Although we did not detect differences in the frequency of silence across cohorts, our qualitative analysis provided insight into variation in how silence was evaluated across cohorts. In the equality cohort, some respondents were simply not willing to accept silence on the topic of same‐sex sexuality from parents any longer, even when their parents were struggling with sexuality as a taboo topic. A rather bold anecdote of an equality cohort Latino male participant is an illustration of this. He described a strategy he used when his mother would not acknowledge his bisexuality: “I tape condoms to my wall, right? I sent her a picture of that. She's like, ‘What are you doing with those?’ I was like, ‘Oh, I use that on guys and girls.’” Respondents in the pride cohort did not describe parents' inability to communicate explicitly about sexual identity in the same fraught terms as those in the equality and visibility cohorts. For example, a White woman respondent from the pride cohort found her mother's silent response amusing rather than upsetting:

We were talking on the phone and I said, ‘So, I am a lesbian, mom.’ She was like, ‘Do you know it was 98 degrees here today.’ I said, ‘Mom, I know you heard me.’ She goes, ‘We don't have to talk about everything.’ [Laughter] It's like, ‘Okay.’

Appraisals Linked to Perceived Invalidating Responses

Many respondents' whose parents appraised same‐sex sexuality negatively also provided an invalidating response to their coming out. Persons in the pride cohort reported negative responses from their parents significantly less often compared to younger cohorts, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 21.96, p < .05 (see Table 1). The qualitative analysis showed themes in underlying conflicts between LGBQ+ identities and a parental belief system that seem relatively unaffected by societal changes, which may go to show the relevance of invalidation even for youth today. First, a highly common theme across cohorts was condemnation of the child's sexual identity on religious grounds as a contextual (societal) factor. For example, using the notion that a religious upbringing can prevent same‐sex sexuality, a White male respondent in the visibility cohort mentioned his father had said: “This isn't what God wants for you, you are going to hell.” Other respondents, regardless of their cohort, mentioned cultural factors as reasons for invalidation: “It's hard, especially, I think, in my culture and in my family. People have this black‐and‐white binary thinking that you have to like one or the other” (woman, equality cohort, Multiracial). Other respondents referred to conservatism in their families (mostly in relation to their father), as a reason for homophobic responses.

In some narratives, negative parental responses originated from a sense of disappointment or loss on the part of the parent for heteronormative traditions and rituals, such as a Black woman in the pride cohort who noted: “My dad was pissed that I deprived him of being the dad who was gonna walk his daughter to the aisle.” This example also describes the impact of heteronormativity in society. Furthermore, some respondents said their parents depicted same‐sex attraction as one of many “deviant” behaviors. As a male Asian respondent in the visibility cohort illustrated: “She [mother] is like, ‘What else are you up to? Are you taking drugs too?’”

Some respondents who mentioned invalidation from parents explained this as related to existing tension in their relationships. A white male participant from the pride cohort had been raised with a rather absent father. He remembers that when he came out to his father: “It was horrible. He was like, ‘I raised you in a catholic upbringing! How could you be telling me this?’ () [Name partner] was there. [Name partner] was like, ‘Fuck him. Whatever. He wasn't there in your life anyway!’” In these cases, rejection from parents was interpreted as reiterating pre‐existing relational difficulties, sometimes in addition to blatant homophobia.

Finally, in two white male participants (both from the visibility cohort), parents immediately focused on HIV/AIDS risk when the respondent came out: “One of the first things he [father] said to me was like, ‘When are you gonna get AIDS?’”

Appraisal Linked to a Mixture of Acceptance and Invalidating Responses

Ambivalence in the appraisal of same‐sex sexuality by respondents' parents coincided with mixed responses. Some respondents said their parents expressed acceptance while they also communicated invalidation (n = 47); these mixed responses were equally present across cohorts, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 4.22, ns (see Table 1). Several categories existed within this theme of mixed invalidation. First, some parental responses demonstrated explicit criticism of the “lifestyle” associated with same‐sex sexualities, although the parents involved here also expressed love. For example, a male American Indian respondent from the visibility cohort described his mother's response: “I don't have to agree with your lifestyle, but you're still my son. I'm still gonna love you.” Some participants reacted with resistance toward the separation their parents had created by framing their disclosed sexual identity as a preference, style or choice. As a Multiracial man from the equality cohort indicated:

I said [to mother], you know what, if you can't accept my happiness and be happy for who I am, then I really don't need people like you in my life. Ever since that, it made my mother and I's bond a bit stronger.

A second category in this theme was characterized by a disconnection between what parents said in response to coming out and how they subsequently behaved. This category was infrequent and consisted of situations in which respondents' mothers had been neutral or accepting when they came out, but then subsequently behaved differently. As a Middle Eastern man from the visibility cohort indicated:

I think it's just never being fully in an environment that's safe. Even at home, even though my mother is neutral about how she feels about my identity, there is a lot of sly negative comments about you're not gonna be accepted.

The third common narrative of mixed acceptance concerned the conditional acceptance of respondents' identities. Restricted visibility was one of those conditions; for example, parents would ask respondents not to bring a same‐sex partner home: “What they [parents] said was that if you're gay or bisexual that's fine but don't bring it around the house” (woman, visibility cohort, Black). A few other respondents said they were confronted with gender expression criteria (and pressures) as conditions of receiving parental validation resulting in a highly conditional or ambivalent form of acceptance. For example, a Black woman in the visibility cohort explained about her mother's attitude:

My mother was neutral first. I invited [a girl] to my house and my mom flipped… had a fit because she was clearly gay. She had her letterman jacket on, her hair was in a ponytail, and she brought this other chick with her who was like eight feet tall.

A fourth, and very common, category of a mixed appraisal resulting in an ambivalent response was one where evaluation of coming out seemed to be contingent on the successful management of family relations. With two exceptions, only respondents of families of color (but not one race in particular) provided this type of response. Responses of this type were only expressed by mothers (who were also often the first person to learn this). Respondents with this narrative said their mother would refrain from a personal evaluation of their sexual identity but quickly pointed out that this information would be a problem for her husband and/or the extended family; some even hinted that the family reputation was jeopardized. As a Multiracial woman from the visibility cohort explained: “She wanted to wait to tell the extended family, my aunts and uncles, her brothers and sisters and their kids. I think a lot of it (…) was because of fear. She's afraid they're gonna judge her, or me, or whatever it is.” This finding thus implies a contextual difference between growing up as an LGBQ+ person in an ethnic minority community, which tends to be more collectivistic in nature than most white US communities (which are arguably more individualistic).

Another type of ambivalent response tapped into contextual factors around gender and gender relations in society. A few women reported responses linked to the sexualization of female same‐sex sexuality. Some mentioned that their fathers had wanted to “check out women” together when they came out, which respondents thought was inappropriate. In two cases, respondents' fathers even tried to flirt with female partners. As a White woman from the pride cohort illustrated: “When I would bring my girlfriend around, he'd make passes at her (…) It was really bizarre. Real incestuous. Very strange.” Some female respondents felt their father's sexualized response signaled that he had not grasped that they were telling him something profound about their identities that deserved respect, although some other respondents felt their fathers were simultaneously also trying to “bond with them,” albeit in “weird” ways. Closely related to the sexualization theme, a Latino woman from the pride cohort mentioned that her bisexuality was understood by her parents as originating from pressure from her husband to engage in sex and relationships with women.

Appraisal Connected to Perceived Validation and Acceptance From Parents

More respondents in the equality cohort reported positive appraisal (expressed through affection, support, being “neutral” or somewhat indifferent) and accompanying validating statements from parents (n = 77) compared to the visibility and pride cohorts, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 45.01, p < .05 (see Table 1). Qualitative results that revealed the five types of rationales for parental validation (as described by their children) provided some ideas for explaining the high frequency in the youngest cohort. First of all, we found a qualitative cohort difference that consisted of parents' knowledge of the term “minority stress” that was reported by a few participants from the equality and visibility cohorts, but not the pride cohort. Knowledge of these stressors seemed to sensitize parents to the importance of acceptance, and the health risks of rejection.

Second, a number of respondents of the equality and visibility cohorts mentioned that their parents viewed their sexual identity as an authentic part of themselves. For instance, as a White woman from the equality cohort quoted her mother: “It is not a flaw, it is who you are.” Somewhat relatedly, some male respondents (again only in the visibility and equality cohorts) said their parents (mostly fathers) expressed their approval based on the idea of personal choice, their children's freedom to do as they wanted in their lives. As a Multiracial man from the equality cohort illustrated his father's reaction: “He said, son, this is your—this is your life. You're an adult. You make your own choices.”

Third, many respondents whose parents had a positive appraisal had someone in their close circle (family member, their boss) who was LGBQ+ and with whom they had a good relationship. Another common rationale was a liberal/open‐minded/feminist/queer supportive family environment. For instance, a Multiracial woman from the equality cohort mentioned that her parents had signaled “wanting to be with the same sex was not bad.” Both rationales (having an LGBQ+ person in their close circle and growing up in an affirmative setting) were found equally across cohorts.

Finally, some respondents said their parents took an egalitarian approach (“sexual orientation blind” approach) to their sexual identity and the gender of their partners. For example, a Latina woman from the equality cohort illustrated how her mother was more focused on socioeconomic class rather than the gender of her partner: “She doesn't really care one way or the other if it's a guy or a girl. She's still like Do they have a good job? Did they go to college?” Other respondents reported that their parents cared most about whether they found someone whose love was true and mutual, while others had parents who pointed out that “same sex relationships are just as difficult to make them work as heterosexual ones” (quote from a Biracial woman in the viability cohort). These reactions about characteristics that would be desirable in a partner were found across all cohorts, but were more common among the equality and visibility cohorts.

Parental Coping Responses

Respondents mentioned their parents had used strategies that seemed focused on reducing the stress involved with their disclosure or confirmation, that is, coping behavior. Respondents listed responses that to a large extent matched avoidant and approach styles of coping (in line with Chrisler, 2017). Avoidant styles were significantly less often reported by respondents in the pride cohort, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 13.70, p < .05 (see Table 1). Avoidant coping mostly consisted of assumptions by respondents' parents that a sexual minority identity was a temporary phenomenon for adolescents, or a “phase.” Some respondents said their parents felt they had been “too young to know what they want” (quote from an Asian woman from the equality cohort). These age‐related convictions may explain the higher frequency of avoidance in the equality and visibility cohort. Equality and visibility cohort respondents seemingly were younger when they came out (based on our impression, missing data prevented a systematic comparison). Additionally, another way through which parents expressed avoidance was through a flat denial of their child's self‐expressed sexual identity, as a Latina participant from the equality cohort illustrated her mother's response: “She was just like, ‘No, you're not. You're not, and so you shouldn't necessarily tell people about that.’” The implied authoritarian tone by parents who expressed a flat denial matches the younger age of respondents of the equality cohort. Again, since quite a few pride cohort respondents were older than respondents in the equality cohort when they came out, this may show the lack of relevance of this theme in the pride cohort.

Respondents' accounts sometimes reflected an approach coping style, similar to those Chrisler (2017) found. Negative approach strategies mostly consisted of bargaining or negotiation on the topic of respondents' identities, which involved downplay of their same‐sex attraction at the favor of (converting back to) a heterosexual life. For example, some female respondents said their mothers had mentioned that they too had experienced “a crush on a woman,” and said this, however, did not mean respondents were LGBQ per se. Moreover, some bisexual respondents mentioned that bargaining by their parents consisted of “lecturing” that they simply could not be attracted to multiple genders. As a Black woman from the equality cohort quoted her parents: “You have to pick one side or the other. That (i.e., bisexuality) is not right. Just lecturing me.” Respondents in the pride cohort reported significantly more negative approach strategies, χ 2(6, n = 155) = 15.96, p < .05 (see Table 1). Perhaps negotiations with respondents seems more appropriate for young adults and adults, as some parents may simply to try to “overrule” teenagers (again, bearing in mind that the pride cohort was often in their 20s, 30s, or 40s when they came out rather than teenagers). Several respondents in the pride cohort mentioned that their parents tried to convince them that they were better off staying in their heterosexual marriage. Respondents in the equality and visibility cohorts also reported negative approach coping from parents (bargaining), but the content seemed inspired by their young age. For example, their parents said they would not be allowed to attend summer camp or a certain school when they found out. Some negative approach strategies seemed relevant regardless of cohort, for example, the suggestion by some respondents' parents that they could to get “healed” through therapy.

Finally, we found very few examples of positive approach coping strategies. Exceptions included respondents who said their parents wanted information about a support group for parents, or one respondent whose parents sought culturally appropriate information about being “two spirited” in order to understand that it exists in American Indian culture.

Discussion

We focused on the complexities and nuances involved in parental reactions to coming out by LGBQ+ US individuals of various ethnicities, and explored potential differences in these reactions among three age cohorts. Chrisler's (2017) analytical framework was suitable for examining the variety of parental purposes in our sample, yet we also needed to adapt and supplement it in order to speak to all complexities we found.

One component of Chrisler's (2017) model that fit our data well addressed the various degrees of suspicion parents may have prior to disclosure. Some parents had no suspicion at all about their children's same‐sex attraction and were shocked and stunned; this theme was more salient in the visibility cohort than in the equality cohort (but also more than in the pride cohort). Our findings supported previous research that revealed more shocked (e.g., rather negative) parental reactions in cohorts that came of age prior to the 1990s (see literature based on data collected in the 1990s, e.g., D'Augelli et al., 1998; Goldfried & Goldfried, 2001). The increased (positive) media and legal attention for same‐sex sexuality over the past decade may play a role in understanding the relatively lower frequency of shock responses from parents indicated by the equality cohort compared to the visibility cohort. The finding that the pride cohort also reported less shock from parents may seem counterintuitive given that many in the pride cohort had been in a heterosexual marriage before coming out to their parents. However, many respondents in the pride cohort did not come out to their parents at all, so there may be a selection effect among those who did tell their parents. The metaphor of parents “lacking a pamphlet” as mentioned by one of our respondents—or lacking a “script” as coined by a parent in Fields's (2001) study—reflects this theme of “shock.” Fields (2001) explains this by pointing out that heterosexuality operates as an organizing principle in society and functions as the standard for legitimate and expected intimate relations. The way heterosexuality as a societal norm impacts the parental expectations of a heterosexual future for their child is also an example of the “contextual factors” in Chrisler's (2017) frame, underpinning macro influences of parental responses to their child's disclosure. (see also Cassar & Sultana, 2016).

Furthermore, some parents' reactions were described as the opposite of shock, that is, certainty about their child's sexuality. This is a modest analytical adaptation to Chrisler's (2017) model that only described “suspecting and nonsuspecting.” Many parents who were described as “certain” had never said anything to their children, and respondents in the equality or visibility cohort in particular who received this feedback had wished for a more communicative approach from their parents, albeit in a respectful manner. “Fishing” or cross‐examinations were not appreciated; LGBQ+ youth in the equality cohort explicitly said they wanted to come out “on their own terms.” Nevertheless, the increasing visibility of (online) LGBQ+ communities emerging in recent decades has enhanced possibilities for LGBQ+ people from the equality and visibility cohorts to more openly affiliate with (online or offline) LGBQ+ communities, thereby also increasing the likelihood of having “suspicious” parents, who may then start “fishing.”

We were also able to apply yet refine Chrisler's components of “parental response” and “parental appraisal.” Silence was a particular parental response in our data that has received some attention in a few studies conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s that suggested that some parents acted as if coming out never occurred (DeVine, 1984; Martin & Hetrick, 1988; Robinson et al., 1989). This is consistent with our finding that, among quite a few respondents, parental silence meant a specific restriction on family communication about sexuality as well as same‐sex sexuality. Although research has previously mentioned parental silence as a response to coming out (Riley, 2010), our study added to this literature by delving into the meaning of parental silence according to LGBQ+ people. As for parental appraisal of their child's disclosure (Chrisler, 2017), we found that silence had connotations beyond hostility/rejection, when some respondents understood parental silence as a marker of the unknown, or as implicit acceptance. Considering the variety of meanings addressed to parental silence (including approving same‐sex sexuality), we assume that silence is more complex than an equivalent to avoidant coping by parents, as Chrisler (2017) argued, which suggests that our study offers a conceptual clarification compared with the initial model.

Invalidating responses from parents were frequent across all cohorts. Thus, although validating statements from parents are on the rise according to young LGBQ+ people in our study, it is too early to state that the tide has turned. Family rejection can have a long‐lasting adverse impact on LGBQ+ people (Puckett et al., 2015), and therefore continues to need researchers' attention. Religious beliefs were often named as a rationale for invalidation, in line with Willoughby et al. (2008) and tapped into frustration among some of respondents' parents. As Fields (2001) argues, parental frustration may be related to the perception that a child's sexual minority identity would reflect something “bad” about them as parents among their friends, which underpins the relevance of the meso factor (contextual component) in Chrisler's (2017) model. Next, considering that public attention to and stigmatization of HIV/AIDS was at its height when the visibility cohort came of age, it is notable that very few male visibility cohort respondents described invalidation from parents in relation to HIV/AIDS risk, in contrast to a previous study on coming out by members in that cohort (Robinson et al., 1989). Furthermore, the fact that the older cohort reported slightly less invalidation could again be attributed to a potential selection effect in those (relatively) few pride cohort participants who decided to come out to their parents.

As suggested by Savin‐Williams and Cohen (2015), LGBQ+ people in the equality cohort were more likely to receive validating responses from parents than older cohorts. Thus, some young LGBQ+ people who grow up as sexual minorities at present seem to reap some benefits from socio‐historical changes in the United States that have led to increasing support for LGBQ+ rights. This finding may also impact the attitudes of LGBQ+ youth who grow up today and who were bolder in their explicit “demands” of parental support, similar to Roe's (2017) finding in a recent young sample. Additionally, the rationale for parental invalidation was somewhat different in the equality cohort; parental messages about the temporality of an LGBQ+ identity and/or expected changes toward heterosexuality in sexual identity (that were also noted by D'Amico et al., 2015) were, with rare exceptions, only found for that cohort. The younger age at which LGBQ+ youth (on average) come out at present may be relevant here, because coming out has changed from an emerging adult experience to an adolescent activity (Dunlap, 2016). The younger age of coming out may also be relevant for understanding why some parents of respondents assumed that deciding for their children who they are in terms of their sexualities seemed appropriate for their developmental stage.

We also noted a qualitative difference in validating reactions across cohorts. The notion of LGBQ+ authenticity and personal choice regarding sexuality was put forward only by parents of the visibility and equality cohort. The fact that individualization processes (Beck & Beck‐Gernsheim, 2002) became more pronounced from the 1960s and 1970s onward, may be relevant here. Parents of pride cohort respondents grew up in an earlier era with less emphasis on “self‐realization” as a goal and were thus less likely to frame sexual identity in such terms. What is more, the idea of same‐sex attraction as a choice has been critiqued as problematic, though some respondents found it worked in their best interest.

We also found evidence of mixed reactions by parents. Parents' arguments for a conditional acceptance of their children may be related to Rubin's (1992) work on how parents draw an imaginary line between good, bad, and abnormal sexual identities, behaviors, and desires. By making their acceptance conditional, parents may have wanted their children to belong to the “right” side of “respectability” in their sexuality and relationships (cf. LaSala, 2000). Furthermore, our analysis shows that ambivalent parental responses may be influenced by race and ethnicity, as predominantly families of color stressed the need for carefully managing family relations by aiming to control further disclosure of their child. This underpins findings by Richter et al. (2017) showing the difficulty of parental approval of same‐sex sexualities in US Latino and Black families. Gender of parents and gender of the child may also play a role in ambivalent responses, as some of respondents' fathers showed a sexualized response, underpinning arguments by Diamond and Butterworth (2008) that gender‐specific research into same‐sex sexuality is needed. More research from the parental perspective would help us better understand the motives behind these complex responses with mixed levels of validation, invalidation or tensions.

Mostly avoidant and negative approach coping was noted among respondents' parents, generally in line with how Chrisler (2017) explained these coping styles that are present in their model. Referral to coming out as “just a phase,” or as an identity that an individual is “too young know about,” was especially found among younger cohorts. This may again reflect the fact many LGBQ+ youth today come out as teenagers rather than as young adults, leading some parents to assume they can mold teenage children. Negative approach coping consisted of various forms of bargaining in favor of heterosexuality, which was also discussed by Savin‐Williams and Ream (2003). Few coping strategies were noted that seemed beneficial for parents' acceptance, showing a need for reaching out to parents and helping them identifying positive coping strategies. Additionally, given the limitations of our data, we were not able to detect Chrisler's (2017) sophisticated categorization of coping styles into cognitive versus behavioral avoidance.

In spite of the advantages of our study in terms of investigating complexities regarding coming out in three LGBQ+ cohorts, several limitations exist. We did not ask the age at which participants came out to parents, so we cannot determine whether younger participants came out more recently. Oral history and life course scholars argue that individuals may reevaluate their perspective of what happened in their families over time (Thompson, 1988). This concern is more salient in the pride cohort, because more time had passed since they came out to parents. Next, although our large sample (n = 155) and the richness of the interview data are strengths of this study, our findings are focused on parents' reactions at the time of coming out, and parental acceptance can change over time, which we could thus not examine (Samarova et al., 2013). Additionally, our study was based on LGBQ+ individuals' feelings and ideas about their parental responses. Future studies could learn directly from parents about their reactions when their child came out to them, because parents may not share all the concerns they have about their children's sexual identity with their children (D'Amico et al., 2015). Next, although recruitment efforts to attract individuals from various educational backgrounds, sexual identities, ethnicities, and communities were successful, it is unclear how representative our sample is to the general LGBQ+ population in the United States. Finally, as our study had its focus on cohort differences, a systematic analysis of race, gender and sexual identity differences was beyond the scope of the study. Arguably, such an approach extends beyond Chrisler's broad analytical frame to arrive at a comprehensive elaboration of the impact of race, gender and sexual identity to coming out to parents.

The study also has implications for practice. Social services and mental healthcare providers working with families could emphasize the desire LGBQ+ youth at present seem to feel for communicating openly with their parents about their sexual identities. Parents who suspect or “have always known” may need some guidance in how to successfully talk with their children about the topic of sexualities. Furthermore, the fact that some respondents of the equality cohort mentioned how their parents were validating but at the same time could not grasp why they had not come out to them earlier suggests that families today need to be made aware that LGBQ+ identities continue to be stigmatized identities in society and therefore make children anxious to disclose. Finally, almost all respondents in our study could vividly remember and narrate their coming out process to parents with great detail. Hence, it can be assumed that a child's disclosure continues to strongly impact the quality of the parent–child relationship, and emphasizes the role of professionals to harmonize conflict and communication issues in families.

This article was edited by Rin Reczek.

References

- Beck, U., & Beck‐Gernsheim, E. (2002). Individualization: Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36(4), 391–409. 10.1023/A:1020909529486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J., & Stanton, M. (2009). The Wiley‐Blackwell handbook of family psychology. Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, V. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235. 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassar, J., & Sultana, M. G. (2016). Sex is a minor thing: Parents of gay sons negotiating the social influences of coming out. Sexuality & Culture: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly, 20(4), 987–1002. 10.1007/s12119-016-9368-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier, E., & Graziani, P. (2016). The stress associated with the coming out process in the young adult population. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(4), 319–328. 10.1080/19359705.2016.1182957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisler, A. J. (2017). Understanding parent reactions to coming out as lesbian, gay, or bisexual: A theoretical framework. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(2), 165–181. 10.1111/jftr.12194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E. (1982). Developmental stages of the coming out process. Journal of Homosexuality, 7(2–3), 31–43. 10.1300/J082v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico, E., Julien, D., Tremblay, N., & Chartrand, E. (2015). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths coming out to their parents: Parental reactions and youths' outcomes. Journal of GLGBT Family Studies, 11(5), 411–437. 10.1080/1550428X.2014.981627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli, A. (2003). Lesbian and bisexual female youths aged 14 to 21: Developmental challenges and victimization experiences. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7(4), 9–29. 10.1300/J155v07n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli, A., Hershberger, S., & Pilkington, N. (1998). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 361–371. 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVine, J. (1984). A systemic inspection of affectional preference orientation and the family of origin. Journal of Social Work and Human Sexuality, 2(3/4), 9–17. 10.1300/J291V02N02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, L. M., & Butterworth, M. (2008). Questioning gender and sexual identity: Dynamic links over time. Sex Roles, 59(5–6), 365–376. 10.1007/s11199-008-9425-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, A. (2016). Changes in coming out milestones across five age cohorts. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 28(1), 20–38. 10.1080/10538720.2016.1124351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fields, J. (2001). Normal queers: Straight parents respond to their children's “coming out”. Symbolic Interaction, 24(2), 165–187. 10.1525/si.2001.24.2.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, F., & Bakeman, R. (2006). Coming‐out across the life course: Implications of age and historical context. Family Studies, 29(4), 287–296. 10.1007/s10508-006-9022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost, D. M., McClelland, S. I., Clark, J. G., & Boylan, E. A. (2014). Phenomenological research methods in the psychological study of sexuality. In Tolman D. L. & Diamond L. M. (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 121–142). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried, M. R., & Goldfried, A. P. (2001). The importance of parental support in the lives of gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(5), 681–693. 10.1002/jclp.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grierson, J., & Smith, A. (2005). In from the outer generational differences in coming out and gay identity formation. Journal of Homosexuality, 50(1), 53–70. 10.1300/J082v50n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov, C., Bimbi, D., Nanin, J., & Parsons, J. (2006). Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming‐out process among lesbian, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Sex Research, 43(2), 115–121. 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiles, D., & Čermák, I. (2008). Narrative psychology. In Hiles D. & Cermák I. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 147–164). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- LaSala, M. (2000). Lesbians, gay men, and their parents: Family therapy for the coming‐out crisis. Family Process, 39(1), 67–82. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, L. (1984). The coming out process for lesbians: Integrating a stable identity. Social Work, 29(5), 464–469. 10.1093/sw/29.5.464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. D., & Hetrick, E. S. (1988). The stigmatization of the gay and lesbian adolescent. Journal of Homosexuality, 15(1/2), 163–183. 10.1300/J082v15n01_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, C. (2000). Family relationships of lesbians and gay men. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1052–1069. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin‐Wallqvist, R., & Lindblom, J. (2015). Coming out as gay: A phenomenological study about adolescents disclosing their homosexuality to their parents. Social Behaviour & Personality, 43(3), 467–480. 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.3.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett, J., Woodward, E., Mereish, E., & Pantalone, D. (2015). Parental rejection following sexual orientation disclosure: Impact on internalized homophobia, social support, and mental health. LGBT Health, 2(3), 265–269. 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek, C. (2016). Ambivalence in gay and lesbian family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(3), 644–659. 10.1111/jomf.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, B. E., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2017). Examining ethnic differences in parental rejection of LGB youth sexual identity. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(2), 244–249. 10.1037/fam0000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, B. H. (2010). GLB adolescent's “coming out.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(1), 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, B., Walters, L., & Skeen, P. (1989). Response of parents to learning that their child is homosexual and concerns over AIDS: A national study. Journal of Homosexuality, 18(1/2), 59–80. 10.1300/J082v18n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe, S. (2017). “Family support would have been like amazing”: LGBTQ youth experiences with parental and family support. Family Journal, 25(1), 55–62. 10.1177/1066480716679651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R. P. (2004). The parental “acceptance‐rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist, 59(8), 830–840. 10.1037/0003066X.59.8.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario, M., Schrimshaw, E. W., & Hunter, J. (2009). Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(1), 175–184. 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, G. (1992). Thinking sex. Notes for a radical theory on the politics of sexuality. In Vance C. (Ed.), Pleasure and danger. Exploring female sexuality. Pandora. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C., Russell, S., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205–213. 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarova, V., Shilo, G., & Diamond, G. M. (2013). Changes over time in youths' perceived parental acceptance of their sexual minority status. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 681–688. 10.1111/jora.12071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin‐Williams, R. C. (1998). The disclosure to families of same‐sex attractions by lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(1), 49–68. 10.1207/s15327795jra0801_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin‐Williams, R. C., & Cohen, K. M. (2015). Developmental trajectories and milestones of lesbian, gay, and bisexual young peopole. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(5), 357–366. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1093465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin‐Williams, R. C., & Dubé, E. M. (1998). Parental reactions to their child's disclosure of a gay/lesbian identity. Family Relations, 47(1), 7–13. 10.2307/584845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin‐Williams, R. C., & Ream, G. L. (2003). Sex variations in the disclosure to parents of same‐sex attractions. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 429–438. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P. (1988). The voice of the past. Oral history. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, B., Doty, N., & Malik, N. (2008). Parental reactions to their child's sexual orientation disclosure: A family stress perspective. Parenting, 8(1), 70–91. 10.1080/15295190701830680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witeck, B. (2014). Cultural change in acceptance of LGBT people. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 19–22. 10.1037/h0098945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]