Abstract

Purpose

With the impending changes to state Medicaid programs and other health reform policies, it is imperative to understand the factors at play in promoting consumer health insurance literacy and health system engagement. This study examines the availability of health system and community‐based programs promoting health insurance literacy and supporting informed consumer health care decision making in rural communities in Kentucky.

Methods

Forty‐six health systems, community‐based providers, and outreach workers participated in 4 focus groups and 10 semistructured interviews. Descriptive and analytic coding techniques were used to identify 5 major themes and subthemes from interview and focus group transcripts.

Findings

Consumers were generally identified as having low health insurance literacy, especially in rural communities, serving as a barrier to accessing health care insurance and services. Participants identified their own lack of knowledge and understanding around health systems, resulting from lack of training and challenges with staying updated on constant changes in health systems and policies. Overall, consumer demand or need for health insurance literacy resources and programs far exceeded supply or availability. Constant changes in the status of Kentucky's Medicaid program and the proposed changes to eligibility, specifically work requirements and copays, have caused increased confusion among both providers and consumers.

Conclusions

Findings indicate a pressing need for implementing programs that provide training, tools, and resources to outreach workers to help them better assist consumers with accessing and using health insurance, especially in low‐income, rural areas. Health reform policies need to be responsive to the health insurance literacy needs and abilities of consumers.

Keywords: access to care, health literacy, insurance, medically uninsured, rural health

Health insurance literacy (HIL), defined as an individual's ability to seek, obtain, and use health insurance, plays a central role in access to coverage and care.1, 2 Unfortunately, low HIL is prevalent in low‐income, vulnerable populations that need coverage the most.3, 4 Rural Appalachian populations could be especially vulnerable as culturally and linguistically tailored health insurance decision‐support programs and resources are largely unavailable.5 Furthermore, the changing landscape of health care reform in the United States places added responsibilities on consumers to be engaged in their health, a task that may be impossible for some due to resource limitations.6

Current changes in state Medicaid programs, including Kentucky's which underwent several changes related to a pending Section 115 waiver (Kentucky HEALTH), represent a timely opportunity to evaluate and address HIL, especially in rural populations that make up 41.6% of Kentucky's population.7 The additional complexity introduced through Medicaid work requirements could adversely impact health insurance coverage and access to care, especially in rural communities that already have disproportionately higher rates of chronic illness and barriers in access to care.8, 9

Current evidence on HIL trends and needs of consumers, especially in rural communities, is limited. However, existing studies indicate that rural residents have lower health literacy rates, which may negatively impact their ability to engage with rural health insurance markets.10, 11, 12, 13 Additionally, it has been found that over half the American population does not understand basic health insurance terms such as deductible, copay, and premium.9 Since the implementation of the ACA, few programs have been developed to assess and support consumers’ decision‐making around selecting, purchasing, and using health insurance.14, 15, 16 Evidence shows that consumers face additional challenges in navigating health insurance markets and health systems without assistance from information intermediaries such as community health workers (CHWs), application assisters, and other outreach workers who are central in translating and transmitting timely health information to consumers.16, 17 However, there are limited data on the capacity of such individuals to be decision coaches and no evidence‐based programs to support training of information intermediaries on improving HIL and supporting health care decision‐making of consumers, warranting the need for further research. To address these gaps, a study was conducted to assess the availability and adequacy of programs and resources promoting HIL and supporting informed consumer health care decision‐making in underserved, rural Appalachian communities in Kentucky.

Methods

A qualitative approach guided by the Social Ecological Model (SEM) of health promotion was utilized to conduct 4 key informant focus groups and 10 in‐depth interviews from September 2018 to May 2019. The SEM provides a theoretical framework to understand how behaviors are shaped by the interactional effects between individual/intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy factors. For the proposed study, factors that impact consumer HIL and informed decision‐making behaviors under each construct of the SEM were emphasized.

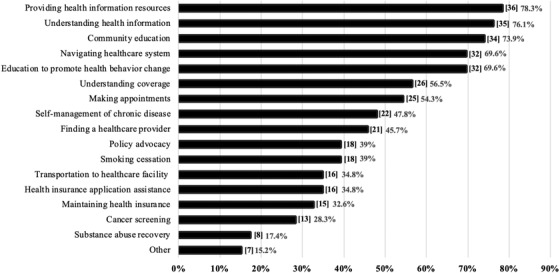

Using purposeful sampling methods, 36 focus group and 10 key informant interview participants were recruited, primarily serving rural Appalachian counties in Kentucky. Participants were recruited in partnership with 2 statewide organizations of CHWs and primary care clinics. Four separate focus groups were conducted with roughly 9 participants in each group representing various roles (see Table 1). Inclusion criteria were adults 18 years or older who identified as working in some type of information intermediary or provider role, assisting consumers with health insurance in Kentucky. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were sent an email with a link to the informed consent, which described the study and gauged interest. Participants received a $25 incentive for participating. The majority of participants reported serving as a health care provider (21.7%), CHW or patient navigator (17.3%), and quality/office coordinator or manager (17.3%) (see Table 1). Most participants reported working in their current role for 3‐5 years (17.3%), were female (78.2%), white (69.4%), between the ages of 35‐44 (30.4%), and served rural areas (42%). The majority of participants reported providing services such as health information resources, community education, and helping consumers understand health information (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group and Interview Participants (N = 46)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| Occupation | |

| Application assistor | 4 (8.6) |

| Health care provider | 10 (21.7) |

| Outreach coordinator | 2 (4.3) |

| Quality/office coordinator or manager | 8 (17.3) |

| CHW or patient navigator | 8 (17.3) |

| County extension agent | 2 (4.3) |

| Counselor/social worker/health educator | 4 (8.6) |

| Missing | 8 (17.3) |

| Years in current position | |

| 0−2 | 5 (10.8) |

| 3−5 | 8 (17.3) |

| 6‐10 | 1 (2.1) |

| 11+ | 3 (6.5) |

| Missing | 29 (63) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 36 (78.2) |

| Male | 3 (6.5) |

| Missing | 7 (15.2) |

| Age | |

| 18‐24 | 1 (2.1) |

| 25‐34 | 11 (23.9) |

| 35‐44 | 14 (30.4) |

| 45‐55 | 3 (6.5) |

| 55+ | 10 (21.7) |

| Missing | 7 (15.2) |

| Education | |

| High school diploma | 1 (2.1) |

| Associate's | 7 (15.2) |

| Bachelor's | 14 (30.4) |

| Master's | 15 (32.6) |

| Doctoral | 2 (4.3) |

| Missing | 7 (15.2) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 1 (2.1) |

| Black/African American | 4 (8.6) |

| White | 32 (69.5) |

| Other | 2 (4.3) |

| Missing | 7 (15.2) |

| Hispanic or Latino | |

| Yes | 3 (6.5) |

| No | 36 (94.1) |

| Missing | 7 (15.2) |

| Populations served | |

| Rural | 19 (42) |

| Urban | 8 (17) |

| Mixed (rural/urban) | 10 (21) |

| Missing | 9 (20) |

Figure 1.

Reported Services Provided by Participants to Community Members (N = 46).

Using a semistructured interview guide, focus groups and key informant interviews examined provider perceptions of the HIL needs and abilities of consumers and how these factors influence the ability of providers to deliver effective, efficient, and equitable health care services. Guided by the SEM, interview guide questions collected data on the quantity and quality of strategies utilized to promote HIL and support informed consumer health care decisions and on the impact of health reform policy changes on the populations the participants served. Sample questions included: What are the health insurance literacy levels of consumers and how do these factors influence the ability to deliver effective, efficient, and equitable health care services? How have recent state health reform policy changes (ie, Kentucky HEALTH) impacted the communities you serve?

All focus groups and interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo version 12 for MacIntosh (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia). Descriptive coding techniques were utilized to organize, categorize, and contextualize data; content analysis was used to analyze the presence, definitions, and relationships between concepts; and analytic coding using line‐by‐line analysis was employed to identify emerging patterns and categorize concepts and themes.18, 19 Two coders coded the data independently before projects were merged in NVivo. Themes and subthemes were discussed and discrepancies were resolved based on interrater reliability scores where Kappa coefficients between .80 and 1 for all subthemes were retained. Subthemes with 7 or more sources and/or references were included in the final analysis (see Table 2) and results below.

Table 2.

Themes Extracted From Focus Group and Key Informant Interviews (N = 46)

| Themes | Subthemes | Source* | References† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme I: HIL levels low | Total | 21 | 53 | |

| System literacy | 8 | 9 | ||

| Low education | 7 | 7 | ||

| Theme II: Consumer barriers to access | Total | 31 | 76 | |

| Understanding | 30 | 98 | ||

| Literacy/language barriers | 11 | 16 | ||

| Confusion | 8 | 10 | ||

| Purchasing/enrolling | 20 | 65 | ||

| Costs | 8 | 12 | ||

| Using | 25 | 130 | ||

| Costs | 12 | 18 | ||

| Social determinants of health | 16 | 129 | ||

| Transportation | 13 | 39 | ||

| Internet and computer access | 11 | 16 | ||

| Theme III: Provider barriers to assisting consumers | Total | 29 | 114 | |

| Lack of knowledge and understanding | 15 | 16 | ||

| Constant changes in health insurance and health systems | 12 | 25 | ||

| Time constraints and decision making | 8 | 9 | ||

| Loss of Kynect | 7 | 12 | ||

| Theme IV: Needed resources | Total | 27 | 159 | |

| In‐person assistance | 15 | 26 | ||

| Centralized source for information | 12 | 15 | ||

| Training | 10 | 11 | ||

| Better communication and support from state | 9 | 12 | ||

| Theme V: State Medicaid waiver impact | Total | 27 | 217 | |

| Confusion and stress for consumers | 19 | 29 | ||

| Confusion for providers | 15 | 36 | ||

| System designed for failure | 15 | 29 | ||

| Premiums and copays | 13 | 21 | ||

| Work requirements | 11 | 17 | ||

Sources refer to the number of participants whose quotes were included under each theme and subtheme.

References refer to the number of total quotes in each theme and subtheme.

Results

Five key themes emerged from the data analysis and are discussed in detail below. Table 2 provides an overview of the themes and subthemes.

Theme I: Low Levels of HIL Among Consumers

Twenty‐one participants (46%) stated that consumers had low levels of HIL and discussed issues ranging from lack of understanding basic health insurance terms and the enrollment process to using their coverage to seek timely and appropriate health care. Understanding and managing costs of care was also expressed as a significant concern among several consumer groups.

For me, the level of health literacy is extremely low. Most people that we serve don't understand some basic stuff like co‐insurance or co‐pays, max out of pocket. …As far as some simple math of saying, if you had a $20 copay and you have a $5000 deductible, do you realize what your bill will look like? Most of them have no idea. (rural CHW)

Lower levels of education were identified as a contributor to low HIL, especially among rural consumers. A lack of system literacy or awareness of how the health care system or health insurance coverage works was a consistent finding among providers and consumers. For example, providers reported difficulties in understanding what services were covered for consumers while at the same time not always understanding how to manage their own care.

Theme II: Consumer Barriers to Access

Understanding, Purchasing, and Using

Thirty participants (65%) identified consumers’ lack of understanding of health insurance as a barrier to accessing needed coverage and 54% identified consumer barriers with using health insurance in a timely and appropriate manner to access care. Limitations in general literacy, especially among rural communities, were highlighted as a barrier to understanding health insurance. Confusion and frustration were reoccurring themes when it came to consumers understanding their health insurance. “Their [consumers] number one complaint is that they consider themselves to be highly intelligent folks and they get confused and frustrated.” High costs of premiums and copays were identified as a barrier to purchasing and using insurance as they often competed with the everyday costs of living. This was especially a burden for the elderly, sick, and disabled. “I have a large population who receives Social Security Disability Insurance and they make too much for the waiver programs but not enough to pay their premium and live.”

Social Determinants of Health

Sixteen participants (35%) identified various social determinants of health impacting consumers’ HIL and their ability to afford health insurance. These include, but were not limited to, lack of adequate health and social services due to policies; lack of public transportation, Internet and computer access; and limited access to healthy food options, adequate housing, and employment. These determinants were especially apparent in rural communities:

A lot of people lost their jobs with the coal mine shut down. In this area that was pretty much all they had…. Owsley is one of the poorest counties in the state, the only revenue is the nursing home and the school system…. If you're at the nursing home making $8 per hour and you're feeding your family on that and you can't help your family with insurance because it's too expensive. (rural CHW)

Internet and computer access were significant barriers in rural communities, as participants indicated that many regions in Appalachian Kentucky do not have broadband access and rely on prepaid phones as their main means of communication. “Internet access is a huge problem—getting online and logging on to email. Some people don't even know what a computer is or have access. Libraries are an hour away.”

The lack of adequate transportation, especially in underserved rural areas, was strongly emphasized as a barrier to accessing health care. Participants serving some rural communities in eastern Kentucky were disturbed by the lack of access to adequate resources in remote areas where consumers who couldn't afford to buy or maintain a car didn't have any other means of public transportation, prompting them to forgo needed health care services:

I remember one particular patient who had heart issues in Lee County, and we needed to send him down the road to a cardiologist. He called and said, ‘I can't go today because I don't have enough money [for transportation].’ (rural CHW)

Theme III: Provider Barriers to Assisting Consumers

Lack of Knowledge and Understanding

Fifteen participants (33%) expressed that they lacked personal knowledge on the nuances of health insurance markets. The changing landscape of health care in the United States, mainly as a result of changing health care policies and the impact they have on health insurance coverage, was a challenge to stay updated on. Additionally, barriers within the health system made it difficult for them to seek and find the information they needed to assist consumers:

A huge barrier to me is that I don't have any particular knowledge in health insurance. I'm an educated individual….. But I don't have any special knowledge of what a plan might or might not cover. (rural county extension agent)

Constant Changes in Health Insurance and Health Systems

Twelve participants (26%) expressed challenges in helping consumers understand their health insurance coverage and keeping consumers constantly updated on changes in coverage and policies. Maintaining lines of communication between insurance companies, providers, and consumers was also a challenge to assisting consumers:

I think our patients are confused with good reason. I am confused. We had a presentation a couple of weeks ago…. I asked a real basic question about the difference between Kentucky Health and MCOs, and so he explained it to me, but I think it's very confusing even to professionals and the community. (urban CHW)

Time Constraints and Decision‐Making

Lack of time for participants and limited decision‐making capabilities of consumers served as a barrier for 8 participants (17%). Enrolling a new client in a health insurance plan can take a minimum of 2 hours and ranges from helping clients with creating an email address to helping them pick the plan that works best for their needs. Additionally, due to low levels of HIL, participants indicated that many of their consumers didn't know which health insurance plans were best for them, serving as a detriment to the shared decision‐making process.

Loss of Kynect

Seven participants (15%) also mentioned the loss of Kynect, Kentucky's former health insurance marketplace, as a barrier to helping consumers purchase health insurance. Kynect employed a statewide network of application assistors, also known as Kynectors, to help disseminate health insurance information and provided in‐person assistance with enrollment. With changes in state administration, the majority of these positions were defunded, leaving many communities without adequate assistance:

When KY administered the health benefits exchange and the Kynectors, the people who helped, I thought that was so helpful. A lot of people got insurance for the first time in their lives. When KY decided not to do that anymore, it became really murky. (rural CHW)

Theme IV: Needed Resources

In‐Person Assistance

Fifteen participants (33%) emphasized in‐person assistance as a much‐needed resource to meet the unique cultural needs of rural communities, who value building trust and maintaining relationships. Having the availability of human resources out in the communities was identified as an effective way to connect and engage consumers.

I think what works best is the community health worker aspect—people get overwhelmed with everything they have to do. They don't have the skills to organize and plan step‐by‐step. They're comfortable coming to someone they trust …and they return to you over and over—it's a lot of work but most people need that kind of thing. Most people need somebody. (rural CHW)

Centralized Source for Information

To address the confusion from continued changes in health policies and insurance plans, 12 participants (26%) emphasized the need for a centralized information source—one that can be updated with pertinent changes that providers can access when assisting clients. Whether this resource hub is a website, toolkit, hotline, flyer or other platform, participants expressed the need for this centralized resource to be a “one‐stop‐shop” for health insurance needs.

Training

As indicated under provider barriers, 10 participants (22%) indicated that their lack of knowledge and information on health insurance could be remedied through a training program. Many mentioned that health insurance assistance is a new and unique skillset that requires specific training. Some suggested having a similar, but abbreviated training program that was provided to certified application counselors/assistors under the ACA.

I think it would be very beneficial to have a basic training or resource guide for people in my position so we could know who to contact. I think that would be a great first line of defense. (rural county extension agent)

Better Communication and Support From State

With the uncertainty surrounding the implementation of Kentucky HEALTH, 9 providers (19%) indicated facing increased confusion. Participants discussed conflicting information sent by the state on Medicaid eligibility, premiums and copays, and implementation timelines caused confusion and chaos for providers and consumers. Consistent and constant communication from the state and adequate support was emphasized as a needed resource to support HIL efforts:

I think KY as a state should be more involved with the oversight of insurance and say that they have to be upstanding and not be playing games with peoples’ lives. But not that you keep changing the rules and tweaking it until you tweak people out of their care. (rural nurse navigator)

Theme V: State Medicaid Waiver Impact

Confusion and Stress for Consumers

Nineteen participants (41%) indicated that the impending changes proposed in Kentucky HEALTH led to confusion, stress, and frustration for consumers as a result of conflicting and inaccurate information. Low HIL of their consumers served as a barrier to understanding and maintaining requirements for Medicaid eligibility in the proposed waiver and in extreme cases fear of losing coverage led to treatment non‐adherence and medication stockpiling:

We had someone who ended up in the hospital because instead of taking their medicine 3 times a day they were taking their meds twice a day so they could save them because they thought their medical insurance was going away. (urban community health navigator)

Confusion for Providers

Fifteen participants (33%) discussed the anticipation and preparation among providers and organizations for changes proposed in Kentucky HEALTH. Although participants were trained on the waiver, constant changes in the status of the waiver, with over 3 iterations and multiple moving parts, led to confusion. Due to lack of accurate information and confusion about changes in coverage, some health care providers assumed that the waiver was in effect and started withdrawing care:

People also think that when the waiver was announced, the expansion went away! I can't tell you how many people thought that. Doctors included. And I can't tell you how many dentists said, well, nope, they're not covered anymore, I can't take care of all of these kids who aren't covered anymore who are scheduled for the summer…. The confusion was mindboggling and intentional. (rural CHW)

System Designed for Failure

Fifteen participants (33%) indicated a mismatch between the proposed programs in Kentucky HEALTH and the needs and abilities of the consumers that it affected. Of particular concern are the work requirements, reinstatement processes, activation of accounts, and out of pocket costs. Several participants voiced their concerns that the system was created to intentionally be complicated to keep people from accessing health insurance and services.

I think it's just a big system fail to begin with, most of the people who are putting these things into place probably have never dealt with, ‘am I going to be able to pay my copay? Can I even afford insurance at all? Or I can afford it for myself but not my kids?’ I think there's a big disconnect between the people up there making those decisions and the people here doing this. (urban CHW)

Premiums and Copays

For most Medicaid recipients, paying out of pocket to cover the cost of premiums and copays is not a familiar activity. Thirteen participants (28%) expressed concerns over the ability of their consumers to pay: One of my members, she didn't have copays one month and then she did the next month. She said, I know it's $3 but it might as well be $1000. So, she stopped taking them [medications]. The cost of keeping coverage and managing cost of care was identified as source of disengaging consumers from the health system.

Work Requirements

Eleven participants (24%) indicated being confused and concerned about connecting consumers to work or community volunteer opportunities (at a minimum of 80 hours per month) and the process of reporting hours. Participants voiced concerns that many underserved communities in Kentucky do not have access to adequate work or volunteer opportunities. Additionally, the lack of career centers, designated centers with personnel to help in finding, maintaining, and monitoring work hours, especially in low‐resourced communities, was identified as a major barrier to keeping consumers engaged with the health system.

The work requirement here is going to be nearly impossible. First of all, there [are] jobs. Lee County alone we had a prison, data entry place—they shut down. Lee County lost about everything they had. So, there is no jobs. (rural outreach coordinator)

Discussion

Findings from this study revealed that the availability and adequacy of HIL and decision‐support programs and resources were limited and, in some cases, lacking in underserved rural communities. Participants stated that the demand or need for HIL resources and programs far exceeded the supply or availability. Limitations in resources were closely linked to the low HIL and unique social determinants of health impacting rural communities in Kentucky, as well as limited access to training and supportive resources for providers and uncertainty of health care reform policies.

Participants perceived that consumers they served had low levels of HIL, especially in rural communities and communities with lower levels of education, which could serve as a barrier to accessing health insurance and health care services. It is widely recognized that the average American consumer has low HIL and struggles with understanding, purchasing, and using their health insurance.3, 4 Our findings are comparable to other studies that have identified low HIL as a barrier to accessing health insurance and health care services.4, 5, 12, 13 Consumers in the United States report feeling confused with health insurance terminology and with the difficulty of navigating a convoluted health care system.20, 21 A national study comparing urban populations with rural populations revealed that rural populations demonstrate lower literacy levels related to health and other types of literacy, which can be explained by known confounders such as education.22 Future studies are needed to further explore the intersection between HIL and social determinants of health to better understand how they impact health care decision‐making in rural populations.

Findings from this study identified employment, transportation, and Internet access as key social determinants that could influence consumer HIL. Uninsured rates remain higher among residents of rural counties compared to urban counties.23 Rural residents who are insured rely heavily on public insurance because of lower incomes, higher poverty and unemployment rates, and limited access to employer‐sponsored insurance when compared to their urban counterparts.24, 25 Transportation is another limited resource in rural regions where nearly 4% of households do not have access to a car and there is limited access to public transportation.26 Limitations in transportation impact rural consumers’ abilities to access in‐person assistance and other resources to help them navigate the health insurance markets. Furthermore, roughly 31% of rural households lack access to broadband Internet, impacting their ability to access, enroll in, and stay connected with health insurance providers.27 A recent survey found that people without access to broadband Internet were significantly less likely to be insured, use telemedicine, use online medical records, or schedule appointments online compared to those without broadband access.28 By addressing these social determinants of health, consumers will be better equipped with tools and resources to purchase health insurance and navigate the health system.

Providers also faced challenges in assisting consumers with understanding, purchasing, and using their health insurance. Participants identified their own limited HIL, resulting from lack of training and difficulty staying updated on constant changes in health systems and policies. A centralized information hub was discussed as a potential solution to assist providers and information intermediaries to stay updated on changes in health insurance coverage and policies. Kynect, Kentucky's former online marketplace platform, successfully helped individuals and families compare health insurance plans, educated the public about their health insurance benefits, and assisted in health insurance plan enrollment.29 Reports have revealed that the dismantling of Kynect in 2016, which provided a centralized information hub, has negatively impacted health insurance enrollment rates and made it harder for providers to access information and keep up with changes.29, 30 The lack of consistent and accurate information on health care policies and coverage has resulted in the risk of losing consumers’ trust in the process of exchanging information. Future programs focused on the development of standardized competencies for providers to effectively promote consumer HIL and informed health care decision‐making are needed. Evidence‐based training and resource hubs are needed to support current information intermediaries and prepare the next generation of individuals who will be disseminating health insurance information to consumers.

Overall, the majority of participants stated that consumer demand or need far exceeded the supply or availability of resources and programs aimed at promoting access to health insurance. Best practices and models for helping improve consumer HIL emphasize the need for in‐person assistance, cultural and linguistic tailoring of resources, and community outreach.16 Compared to usual care, decision coaching provided by information intermediaries, such as CHWs, can significantly improve knowledge, participation, and satisfaction with the decision‐making process among consumers.31 However, as the number of available information intermediaries dwindles due to lack of funding, underserved communities face additional barriers to gaining assistance.32 Future programs are needed to continue building on the work that Kynect and other successful outreach programs have implemented in providing in‐person assistance to communities that need it the most. The lack of technology, limited access to services, and culturally driven need for building trusted relationships among rural communities emphasizes the need for trained, in‐person information intermediaries.

Participants discussed the impact that Kentucky's proposed Section 1115 Medicaid waiver, Kentucky HEALTH, can and has already had on consumers’ health insurance needs and how it impacted consumer HIL. During the course of this study, Kentucky HEALTH underwent several changes. It was first granted approval by CMS in January 2018, but it was quickly followed by a lawsuit, which led to Judge Boasberg of the D.C. District Court remanding the waiver back to HHS for further review, halting its implementation in June 2018. The waiver was once again approved by CMS with minimal changes in November 2018 and went back to court in March 2019 where Judge Boasberg once again sent the waiver back to CMS for further review. In December 2019, a newly elected Kentucky Governor rescinded the waiver in its entirety, maintaining Medicaid expansion in Kentucky. During this back‐and‐forth, different aspects of the waiver were still being implemented at different periods of time when the waiver was temporarily approved. This included suspension of dental and vision coverage for certain Medicaid enrollees and mandatory Medicaid copays. The majority of participants in this study indicated that the constant changes in the status of the waiver and the proposed changes to Medicaid eligibility, specifically work requirements and copays, caused increased confusion among both providers and consumers. A recent report that explores the experiences of individuals who participated in the implementation of Section 1115 Medicaid waivers in Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, and Michigan, share similar concerns as current study participants.32 The report repeatedly emphasized the need for additional administrative support and concerns regarding limited outreach and education to consumers. Systematic barriers in addition to confusion and low levels of HIL place rural underserved communities at risk of misinterpreting the implications of the waiver. Work requirements represent a barrier to access in a population currently struggling to use the services and benefits that are already available due to socioeconomic factors. From a public health perspective, the proposed state Medicaid waiver has the potential to introduce a new group of uninsured or underinsured individuals who will require additional supports and services to seek, select, enroll in, and effectively use their insurance to meet health care needs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to take into consideration with interpreting findings from this study. The study findings represent the HIL challenges in a sample of providers in predominantly rural, Appalachian communities of Kentucky using a qualitative approach. Therefore, findings may not be generalizable to other regions of the state, other states, or other rural regions in the United States. Using purposeful sampling methods could have introduced selection or sampling bias, leading to the omission of other relevant health service roles and providers in urban regions and/or other perspectives on this issue. Confirmation bias could have also influenced these findings; however, researchers took every opportunity to challenge preexisting assumptions and hypotheses. Policy implications must be interpreted cautiously as state Medicaid and waiver policies differ across states and continue to change.

Conclusions

This study provides crucial evidence on the availability of programs and resources that support informed consumer health care decision‐making with a focus on improving consumer HIL. The HIL of all populations, especially those in underserved rural areas, has major implications for accessing and utilizing health care services and ultimately a population's overall health outcomes. Results from this study indicate a pressing need for implementing standardized training programs that provide training, tools, and resources for outreach workers to help them better assist consumers, especially in low‐income, rural areas, with accessing and using health insurance. Health reform policies should continue taking into account the social determinants of health that impact consumer HIL, especially among rural health care consumers. It is imperative that future studies continue to address the impact that our current health system and associated policies have on consumer HIL and vice versa.

Edward J, Thompson R, Jaramillo A. Availability of health insurance literacy resources fails to meet consumer needs in rural, Appalachian Communities: implications for state Medicaid waivers. The Journal of Rural Health. 2020;00:00‐00. 10.1111/jrh.12485

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the Kentucky Association of Community Health Workers, the Kentucky Primary Care Association, and the University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service .

Disclosures: The authors individually and collectively declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This study was funded by a University of Kentucky College of Nursing Pilot Research Grant.

References

- 1.Newkirk V, Damico A. The Affordable Care Act and Insurance Coverage in Rural Areas. Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. Available at https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-act-and-insurance-coverage-in-rural-areas/. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- 2.Pollard K, Jacobsen LA. The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview From the 2010–2014 American Community Survey. Washington, DC: Appalachian Regional Commission; 2016. Available at https://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/DataOverviewfrom2010to2014ACS.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- 3.Lane NM, Lutz AY, Baker K. Health Care Costs and Access Disparities in Appalachia. Washington, DC: Appalachian Regional Commission; 2012. Available at http://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/healthcarecostsandaccessdisparitiesinappalachia.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2019.

- 4.Quincy L. Measuring Health Insurance Literacy: A Call to Action. Washington, DC: Consumers Union; 2012. Available at http://consumersunion.org/research/measuring-health-insurance-literacy-a-call-to-action. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 5.Paez KA, Mallery CJ, Noel H, et al. Developing of the health insurance literacy measure (HILM): conceptualizing and measuring consumer ability to choose and use private health insurance. J Health Commun. 2014;19(2):225‐239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long S, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, et al. The health reform monitoring survey: addressing data gaps to provide timely insights into the affordable care act. Health Aff. 2014;33(1):161‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Commerce. Economics and Statistics Administration. US Census Bureau. Kentucky: 2010. Washington, DC; 2012. Available at https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-19.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 8.Kenny GM, Karpman M, Long SK. Uninsured Adults Eligible for Medicaid and Health Insurance Literacy. Washington DC: The Urban Institute; 2013. Available at http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/medicaid_experience.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 9.American Institutes of CPAs. Half of U.S. adults fail ‘health insurance 101,’ misidentify common financial terms in plans; 2013. Available at http://blog.aicpa.org/2013/09/half-of-us/adults-fail-health-insurance-101.html#sthash.OIBOjPxE.dpbs. Accessed August 24, 2019.

- 10.Zahnd, WE, Scaife SL, Francis ML. Health literacy skills in rural and urban populations. National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. Rural Health Insurance market challenges; 2018. Available at https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/publications/2018-Rural-Health-Insurance-Market-Challenges.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 12.Politi MC, Kaphingst KA, Kreuter M, Shacham E, Lovell MC, McBride T. Knowledge of health insurance terminology and details among the uninsured. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(1):85‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinaiko AD, Ross‐Degnan D, Soumerai SB, Lieu T, Galbraith A. The experience of Massachusetts shows that consumers will need help in navigating insurance exchanges. Health Aff. 2013;32(1):78‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein RM.Real decision support for health insurance policy selection. Big Data. 2016;4(1):14‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kullgren JT, Galbraith AA, Hinrichsen VL, et al. Healthcare use and decision making among lower‐income families in high‐deductible health plans. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1918‐1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovannelli J, Curran E.Factors affecting health insurance enrollment through the state marketplaces: observations on the ACA's third open enrollment period. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2016;19:1‐12. PMID:27459742 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Braun B, Williams AD. Understanding health insurance literacy: a literature review. Fam Consum Sci. 2013;42(1): 3‐13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carley K. Content analysis. In Asher RE, ed. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Edinburgh: Pergamon Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss A, Corbin J.Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedure for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edward J, Wiggins A, Young M, Rayens MK. Significant disparities exist in consumer health insurance literacy: implications for health care reform. Health Liter Res Pract. 2019;3(4):e250‐e258. PMID:31768496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edward J, Morris S, Mataoui F, Granberry P, Williams MV, Torres I. Access to healthcare for Spanish‐speaking Hispanic/Latino communities: the role of health literacy and health insurance literacy. Public Health Nurs. 2018;35(5):176‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zahnd WE, Scaife SL, Francis ML. Health literacy skills in rural and urban populations. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(5):550‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Census Bureau. Health insurance in Rural America. 2019. Available at https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/health-insurance-rural-america.html. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 24.Rural America at a Glance: 2016 Edition. USDA. Available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/80894/eib162.pdf?v=42684Xx. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 25.“The Urban‐Rural Divide in America.” March 29, 2017. Available at http://www.realclearpolicy.com/articles/2017/03/29/the_urban-rural_divide_in_america.html. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 26.American Public Transportation Association . Rural communities expanding horizons: the benefits of public transportation. 2012. Available at https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/Resources/resources/reportsandpublications/Documents/Rural-Communities-APTA-White-Paper.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 27.Federal Communications Commission. 2018 Broadband Deployment Report. https://www.fcc.gov/reports-research/reports/broadband-progress-reports/2018-broadband-deployment-report. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 28.Communicating for America. Rural broadband and health impact survey; 2019. Available at https://www.communicatingforamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CA-Rural-Broadband-Survey-Sept-2019.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 29.Artiga S, Tolbert J, Rudowitz R. Implementation of the ACA in Kentucky: Lessons Learned to Date and the Potential Effects of Future Changes. Lexington, KY: Kentucky Family Foundation; 2016. Available at http://kff.org/report-section/implementation-of-the-aca-in-kentucky-issue-brief/. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 30.Norris L. Kentucky health insurance marketplace: history and news of the state's exchange; 2019. Available at https://www.healthinsurance.org/kentucky-state-health-insurance-exchange/. Accessed August 25, 2019.

- 31.Bronfrenbrenner U.The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zylla E, Planalp C, Lukanen E, Blewett L. Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers: implementation experiences (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission); 2018. Available at https://www.macpac.gov/publication/section-1115-medicaid-expansion-waivers-implementation-experiences/. Accessed August 27, 2019.