Abstract

Introduction

Mechanical ventilatory is a crucial element of acute brain injured patients’ management. The ventilatory goals to ensure lung protection during acute respiratory failure may not be adequate in case of concomitant brain injury. Therefore, there are limited data from which physicians can draw conclusions regarding optimal ventilator management in this setting.

Methods and analysis

This is an international multicentre prospective observational cohort study. The aim of the ‘multicentre observational study on practice of ventilation in brain injured patients’—the VENTIBRAIN study—is to describe the current practice of ventilator settings and mechanical ventilation in acute brain injured patients. Secondary objectives include the description of ventilator settings among different countries, and their association with outcomes. Inclusion criteria will be adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury or cerebrovascular diseases (intracranial haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke), requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation and admission to the ICU. Exclusion criteria will be the following: patients aged <18 years; pregnant patients; patients not intubated or not mechanically ventilated or receiving only non-invasive ventilation. Data related to clinical examination, neuromonitoring if available, ventilator settings and arterial blood gases will be recorded at admission and daily for the first 7 days and then at day 10 and 14. The Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended on mortality and neurological outcome will be collected at discharge from ICU, hospital and at 6 months follow-up.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Ethic committee of Brianza at the Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale-Monza. Data will be disseminated to the scientific community by abstracts submitted to the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine annual conference and by original articles submitted to peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, neurological injury, neurophysiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Results from this large multicentre study including mechanically ventilated acute brain injured patients admitted to the intensive care unit, will provide a detailed description of the patients’ characteristics, ventilator strategies and their association to clinical outcomes.

The main strength of this study relies on the global approach, since it allows to explore clinical practice in a wide number of geographical regions with different public health issues, including low-income and middle-income countries.

The main limitation of this study relies on the observational design, with consequent difficulty to draw causal inferences.

The results from this study will generate hypotheses for respiratory management of acute brain injured patients and help in better study design plans for future randomised controlled trials.

Background and rationale

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is a frequently applied and often a life-saving strategy in severely brain injured patients.1 However, paradoxically, ventilation itself has the potential to cause further pulmonary and cerebral damage and can increase mortality and morbidity.2 Several experimental and clinical studies have shown how brain injury can cause secondary lung injury.2–4 Lung injury could be due either to MV, which is often necessary in brain injured patients, or to inflammatory response that follows primary acute brain injury, or a combination of both mechanisms.5

The so-called ‘protective lung ventilation’ strategies include the use of low tidal volume (TV), positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) and eventually recruitment manoeuvres (RMs), and are aimed to prevent lung damage and to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).6 7 In particular, the use of low TV seems to have the greater importance,8–11 and it is recommended in critically ill patients with ARDS.12

Results from one multicentre randomised controlled trial suggest that intensive care unit (ICU) patients without ARDS could also benefit from ‘protective lung ventilation strategies’.13A recent meta-analysis showed a higher incidence of pulmonary complications and even increased mortality in patients who received ‘conventional ventilation’ with traditionally sized or higher TVs compared with patients undergoing protective strategies.14

Therefore, the concept of ‘protective lung ventilation’ has led to a clinical approach, which seems to reduce morbidity and mortality of ICU patients with ARDS but can also have a beneficial effect on patients with healthy lungs and in the perioperative settings. However, these recommendations often come into conflict with the management of patients affected by acute brain injury, because low TVs, high PEEP and RMs can increase carbon dioxide (CO2) and increase intrathoracic pressure, thus having detrimental effects on intracranial pressure (ICP) and cerebral perfusion pressure.15–17 Because of this, brain injured patients have been traditionally excluded from the major trials regarding MV. There is therefore still uncertainty regarding the use of protective ventilation strategies in brain injured patients and, as pointed out by a recent consensus of experts,18 a multicentre international study on MV strategies in this cohort is currently needed.

Methods

Study design

We designed a large international multicentre prospective observational cohort study including mechanically ventilated brain injured patients and planned 6-month follow-up.

Objectives

Primary objective is to describe ventilation settings of intubated and mechanically ventilated neurocritically ill patients admitted to the ICU.

Secondary objectives are:

To describe the differences in ventilator settings among different countries.

To evaluate the association of ventilator settings with pulmonary complications (including pneumonia, acute distress respiratory failure, neurogenic pulmonary oedema).

To describe differences in the ventilator settings in presence/absence of high ICP.

To evaluate the association of ventilator settings with outcomes (ie, 6 months mortality and neurological outcome, in-hospital and ICU mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), duration of MV, ventilator free days at ICU discharge).

Study population

We will collect data of consecutive patients with acute brain injury requiring endotracheal intubation and MV, who are admitted to the ICU.

Inclusion criteria will be

Age >18 years.

Patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of a primary non-anoxic brain injury, such as

Traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Cerebrovascular diseases (intracranial haemorrhage, ICH; subarachnoid haemorrhage, SAH; acute ischaemic stroke, AIS).

Patients requiring intubation, or MVbefore or during ICU stay.

Exclusion criteria

Age <18 years.

Pregnant patients.

Patients not intubated or not mechanically ventilated or receiving only non-invasive ventilation (ie, patients who never received invasive ventilation during the present admission).

Outcomes

Enrolled patients will be followed up until ICU-hospital discharge or death, whatever comes first and at 6 months follow-up.

Outcomes will be assessed as:

Six months mortality and neurological outcome (as for Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, GOSE).

Pulmonary complications (defined as: acute distress respiratory failure, pulmonary infection, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, atelectasis, non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema).

In-hospital and ICU mortality.

Hospital LOS in patients discharged alive.

Duration of MV (in days), ventilator free days (days) at ICU discharge.

Study procedures and settings

The protocol has been endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Worldwide, more than 200 centres from 56 countries have been contacted to participate in the VENTIBRAIN study (more information at https://www.esicm.org/research/trials/endorsed-trials/ongoing-projects-endorsed/).

The established recruitment window will open in summer-autumn 2021. The inclusion period will be flexible for participating centres and determined at a later stage together with the study coordinator. Centres will enrol consecutive patients for a minimum period of 3 months to a maximum period of 6 months.

Patients in participating centres will be screened on a daily basis. After 6 months from recruitment, the patients or their family members will be contacted by phone for the follow-up evaluation.

Data collection

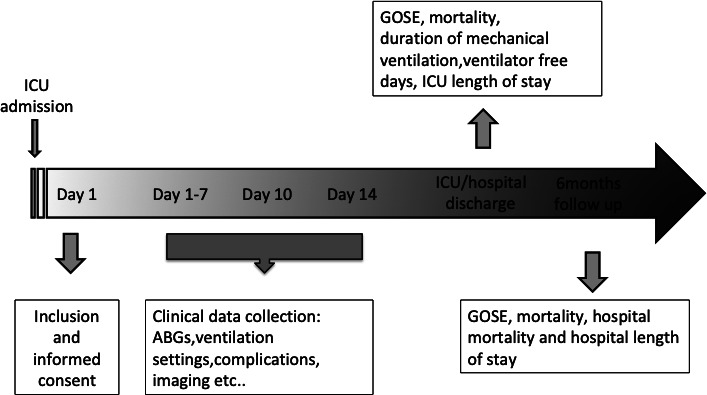

The following data will be collected at admission, and daily until day 7, and then at days 10 and 14 (figure 1):

Figure 1.

Timetable of the study. ABGs, arterial blood gases; GOSE, Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; ICU, intensive care unit.

Demographic data and baseline clinical data, including neurological, neuroradiological and respiratory severity scores (tables 1–4), neuromonitoring data and the occurrence of neurological and systemic complications.

Ventilator settings, in particular: modality of ventilator, TV, plateau pressure, peak pressure, mean airway pressure, PEEP, respiratory rate, inspired fraction of oxygen.

Gas exchange variables and vital parameters.

Chest radiography data from available chest X-rays and/or Computed Tomography (ie, no extra chest X-rays are obtained).

Therapy intensity levels and predefined complications recorded from medical chart (table 5).

Table 1.

The Berlin definition of ARDS.

| Criteria | Definition | ||

| Cause | Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload; need objective assessment to exclude hydrostatic oedema if no risk factors present (eg, echocardiography). | ||

| Timing | Within 1 week of a known clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms. | ||

| Chest imaging (Chest XRay or CT scan) | Characteristics of the lung images | ||

| Oxygenation | Mild 200<PaO2/FiO2≤300 PEEP or CPAP ≥5 cm H2O |

Moderate 100<PaO2/FiO2≤200 PEEP ≥5 cm H2O |

Severe PaO2/FiO2≤100 PEEP ≥5 cm H2O |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; PaO2, arterial oxygen tension; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Table 2.

Glasgow Coma Scale

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Eyes | Does not open eyes | Opens eyes in response to pain | Opens eyes in response to voice | Opens eyes spontaneously | N/A | N/A |

| Verbal | Makes no sounds | Makes sounds | Words | Confused, disoriented | Oriented, converses normally | N/A |

| Motor | Makes no movements | Extension to painful stimuli (decerebrate response) | Abnormal flexion to painful stimuli (decorticate response) | Flexion/withdrawal to painful stimuli | Localises to painful stimuli | Obeys commands |

N/A, not available.

Table 3.

Marshall classification of traumatic brain injury

| Diffuse injury I (no visible pathology) |

|

| Diffuse injury II (swelling) |

|

| Diffuse injury III |

|

| Diffuse injury IV (shift) |

|

| Evacuated mass lesion V |

|

| Non-evacuated mass lesion VI |

|

Table 4.

Fisher scale

| Grade 1 |

|

| Grade 2 |

|

| Grade 3 |

|

| Grade 4 |

|

ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Table 5.

Therapy intensity-level scale

| ITEM | Details | Specifics | Score | Max |

| Positioning | Head elevation for ICP control | 1 | 1 | |

| Nursed flat (180°) for CPP management | 1 | |||

| Sedation and neuromuscular blockade | Low-dose sedation (as required for mechanical ventilation) | 1 | 8 | |

| Higher-dose sedation for ICP control (but not aiming for burst suppression) | 2 | |||

| High-dose propofol or barbiturates for ICP control (metabolic suppression) | 5 | |||

| Neuromuscular blockade (paralysis) | 3 | |||

| CSF drainage | CSF drainage—low volume | <120 mL/day (<5 mL/hour) | 2 | 3 |

| CSF drainage—high volume | ≥120 mL/day (≥5 mL/hour) | 3 | ||

| CPP management | Fluid loading for maintenance of cerebral perfusion | 1 | 2 | |

| Vasopressor therapy required for management of cerebral perfusion | 1 | |||

| Ventilatory management | Mild hypocapnia for ICP control, based on arterial CO2 in mm Hg | ≥35, <40 | 1 | 4 |

| Moderate hypocapnia for ICP control | ≥30, <35 | 2 | ||

| Intensive hypocapnia for ICP control | <30 | 4 | ||

| Hyperosmolar therapy | Mannitol | ≤2 g/kg/24 hours | 2 | 6 |

| Mannitol | >2 g/kg/24 hours | 3 | ||

| Hypertonic saline | ≤0.3 g/kg/24 hours | 2 | ||

| Hypertonic saline | >0.3 g/kg/24 hours | 3 | ||

| Treatment of fever (T>38°C or spontaneous T<34.5°C) | 1 | |||

| Cooling for ICP control,≥35°C | 2 | |||

| Hypothermia <35°C | 5 | |||

| Intracranial operation for progressive mass lesion, NOT scheduled on admission | 4 | |||

| Decompressive craniectomy | 5 | |||

| Maximum total possible score | 38 | |||

CO2, carbon dioxide; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ICP, intracranial pressure.

At ICU and hospital discharge, data on mortality, LOS (days) duration of MV (in days), ventilator-free days (days) will be collected.

At 6 months, mortality and neurological outcome (as for Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale, GOSE, table 6) will be collected.

Table 6.

Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale

| Category no | Definition |

| 1 | Upper good recovery |

| 2 | Lower good recovery |

| 3 | Upper moderate disability |

| 4 | Lower moderate disability |

| 5 | Upper severe disability |

| 6 | Lower severe disability |

| 7 | Vegetative state |

| 8 | Death |

The GOSE at 6 months follow-up will be collected via phone-structured interviews to the patients and/or family members using a validated questionnaire.19Data on the cause and date of death will be also collected.

Data management

Anonymised data will be collected in a web-based electronic case report form (CRF) and protected by encryption software and password provided to single users. Each patient will be associated to a numeric code generated by the central database. Data will be checked for consistency and completeness by the study coordinator and the core steering committee, to ensure the high quality of the collected data before the analysis and to limit the rate of errors and missing data. Also, a strict monitoring of data quality during the study will be performed.

The data will be securely stored at the University Milano-Bicocca; all procedures will comply with the EU Regulation 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons regarding personal data processing and movement. A data transfer agreement to confirm the terms for data transfer from the centres to the sponsor will be finalised.

Patients’ demographic characteristics, comorbidities, diagnosis, timing of acute events and clinical presentation of acute brain injury will be extracted from the patients’ medical records.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

Since the hypotheses of the study are exploratory, no formal sample size calculation has been performed. This international prospective observational study aims to recruit more than 2000 patients after acute brain damage. Recruitment will last 3–6 months at each centre, aiming to enroll an average of 30 consecutive patients/centre. This time frame has been set according to a previous study20 similar to VENTIBRAIN, and including a similar network of centres. The number of enrolled patients and ICUs is considered adequate to capture the range of variation in ventilator settings observed in the clinical practice. We aim to include also low-middle income countries, in order to have a representation of the variability worldwide.

Plan of analysis

Patient and ventilation characteristics will be described by means (SD), medians (I–III quartiles) and proportions, as appropriate. The different ventilator settings will be described according to type of brain injury (ie, TBI, ICH, AIS and SAH), presence and severity of lung damage and countries. The association between daily ventilator settings and outcomes will be evaluated by appropriate multivariable models adjusting for relevant confounders at baseline (such as age, sex, cardiovascular and neurological history, primary diagnosis, Glasgow Coma Scale, pupillary reactivity and the severity of pulmonary and neurological conditions). We will explore the role of currently known thresholds for other ICU populations of ventilator settings; however, as in this population no specific thresholds have been defined, we will aim to assess the distribution of these settings and eventually define new thresholds for the brain injured population.

Cause-specific Cox model will be applied to time to event outcomes (ie, mortality, pulmonary complications) and logistic regression to dichotomous outcomes (ie, poor neurological outcome at 6 month, GOSE <5). Multilevel regression models will be applied to account for repeated measurements on patients and heterogeneity induced by centres and, if residual variation is present, by countries.

The cumulative incidence in time of pulmonary complications during hospital stay will be estimated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) accounting for mortality and discharge as competing events by the Aalen-Johansen estimator.

The occurrence of raised ICP value lasting more than 5 min>20 mm Hg will be described daily together with the earlier ventilator settings. A multilevel longitudinal model on daily raised ICP will be also applied to evaluate the possible impact of ventilator settings adjusting for relevant confounders (as defined before); this model will include only ICP monitored patients.

A sensitivity analysis excluding data from centres that recruited less than 20 patients will be performed. Multiple imputation on covariates will be performed if missing data will exceed 10%. Statistical analyses will be conducted using R.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Ethical considerations

Ethical standards

The PI and Steering Committee will ensure that this study is conducted in full conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices.

Ethics committee

Each NC (national Coordinator)/ PI (local Principal Invastogator) will notify the relevant ethics committee, in compliance with the local legislation and rules. The national coordinators will facilitate this process. The approval of the protocol (if required by local authorities) must be obtained before any participant is enrolled. Any amendment to the protocol will require review and approval by the SC before the changes are implemented to the study.

Lack of capacity and delayed consent

Informed consent will be obtained from patients with no lack of capacity. For patients not able to provide informed consent at the time of recruitment, the responsible clinical/research staff will act as consulter and consent eligible patients after discussion with the next of kin. If the patient has a power of attorney or a legal tutor or an, he/she will act as consultee and will be asked to consent/decline participation to the study on legal behalf of the patient.

In presence of patients’ advance decision plan, including participation in research studies, the plan will be respected and recruitment pursued/abandoned accordingly. At follow-up, patients who have regained capacity will be asked to provide informed consent and will be given the possibility to:

Provide informed consent for the acute data and follow-up.

Deny research participation and request destruction of acute data collected.

Dissemination

Data will be disseminated to the scientific community by abstracts submitted to the ESICM annual conference and by original articles submitted to peer-reviewed journals.

Publication and data sharing policy

Data sharing policy

After the publication of the main papers, any requests for the use of the data will be made to the VENTIBRAIN Core Steering Committee (CR, GC, PP and FT), and decisions will be made in relation to these requests. The VENTIBRAIN investigators will have priority in requests to use the data set for subsequent studies.

Publication and authorship

Data will be made available to the scientific community by means of abstract by scientific papers submitted to peer-reviewed journals. Authorship of the main manuscript will follow the ICMJE recommendations that base authorship on the following four criteria:

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work.

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Final approval of the version to be published.

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

A writing committee composed by the members of the core steering committee and biostatisticians and a part of the enlarged steering committee will draft the manuscript and will be author of the manuscript. National coordinators will be authors if they will fulfil the ICMJE criteria and if they will promote the enrolment of at least 300 patients in their country. All the participant centres will be granted in the group authorship, ‘VENTIBRAIN’. The corresponding author will specify the group name and will clearly identify the group members who can take credit and responsibility for the work as collaborators. For each centre, a participant will be indicated in the group authorship list every 10 patients enrolled. The ESICM support will be acknowledged in each publication generated from the study. In the main manuscript, CR will have the first authorship, and PP will be the last author. After publication of the primary results, on request, the pooled dataset will be available for all members of the VENTIBRAIN collaborators for preplanned substudies and secondary analysis, after judgement and approval of scientific quality and validity statement guidelines and checklists. Each secondary analysis or substudy approved will have to include the core steering committee as authors. Preplanned analyses include the evaluation of blood gas values (such as oxygen and CO2) and their association with patient’s outcome, and the assessment of mechanical power used in this cohort of patients and its effect on outcomes.

Discussion and expected impact of the study

VENTIBRAIN is designed to obtain a detailed description of patient’s characteristics, management strategies resource use and association with clinical outcomes across many centres/countries. In particular, the study will provide insights in relation to clinical management, monitoring and treatment, practice variation in neuro-ICUs around the world, differences in the ventilator management of brain injured patients and their potential association with outcome.

VENTIBRAIN has several strengths. First, its prospective design will increase the accuracy of data collection with potential minimization of the chance of residual confounding by unmeasured variables, which is a common limitation of retrospective designs. Second, we aim to obtain a large sample size, able to provide information on neurological and systemic complications in mechanically ventilated brain injured patients, and eventually evaluate potential associations between ventilator settings and ICU/ 6 months patients’ outcomes. Third, the inclusion of a large number of patients from different centres (dedicated and not dedicated neuroICUs) and countries, including low-income countries will provide information on geoeconomics differences in epidemiology, management strategies and outcomes of mechanically ventilated brain injured patients.

The need to particularly focus on the mechanical ventilator settings in this group of patients is related to the specific ventilator needs of brain injured patients.18 21 Brain injured patients have a high number of pulmonary complications, ventilator associated pneumonia, and a high rate of need of tracheostomy and extubation failure.22

The optimal oxygenation and CO2 targets are not clear in this population.

Hypoxia has been largely recognised as a major cause of secondary brain injury; recently, also hyperoxia has shown to have potential detrimental effects on patients’ outcome.23 24

Similarly, hypercapnia can cause cerebral vasodilation and increase ICP and should therefore be avoided, but hypocapnia and cerebral vasoconstriction can lead to cerebral ischaemia and currently it is suggested only in case of life-threatening intracranial hypertension and risk of brain herniation.25 26

All in it, ventilator targets are unclear in this group of patients.

Moreover, the general principles and ventilator settings applied in the general population have not been established in brain injured patients.19

Recent literature has highlighted the importance of protective ventilation in ARDS and non-ARDS patients,27–32 as well as weaning protocols. However, country-specific practices, the lack of clear guidelines in the neuro-ICU population or different resources among countries may affect the implementation of all these interventions.

Protective ventilator strategies such as high PEEP or RM may increase intrathoracic pressure and consequently reduce jugular outflow33; low TV and permissive hypercapnia may be detrimental in this group of patients and rescue therapies used in ARDS patients such as prone position cancarry the risk of increased ICP and neuromonitoring tools displacement. Finally, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation can be contraindicated for the risk of haemorrhage.34However, although these patients have been traditionally ventilated with high TVs and low PEEP,29 recent evidence suggests that the concept of protective ventilation is gaining interest even in the brain injured population.19

Results from the VENTIBRAIN study will allow to clarify the current status of the ventilator management of these patients, and in particular to discriminate the effects of TV, PEEP and driving pressure on outcomes in brain injured patients with, at risk of or without acute distress respiratory pressure (using predefined scores), and the use of specific settings in case of intracranial hypertension. The VENTIBRAIN study offers a unique opportunity to globally uniform clinical guidelines regarding ventilator strategies in brain injured patients and eventually improving their outcome.

The VENTIBRAIN study has also several limitations that need to be addressed. First, we cannot exclude that ventilator settings and targets used by clinicians might be biased by the participation in the study, thus reducing the ability of VENTIBRAIN to represent the real ICU care of these patients. Second, the CRF designed for VENTIBRAIN was aimed to avoid excessive workload for the participating centres. Therefore, some data regarding systemic complications will be potentially missing, while continuous data on respiratory and neuromonitoring might be incomplete. Similarly, due to the limited number of daily arterial blood gases and ventilator settings data collection, we will have a limited view that might not reflect completely real clinical practice.

Finally, the observational nature of VENTIBRAIN makes impossible to draw causal inferences between ventilator management and outcome in this group of patients.

VENTIBRAIN is designed to assess and describe the clinical practice in ventilator strategies in critically ill brain injured patients in a large number of different countries/centres worldwide. Results from this study will help to identify differences in clinical practices and could be used to plan new trials on MV in this specific subgroup of patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @chiara_robba, @dr_Cit

CR and GC contributed equally.

Collaborators: Maura Mandelli, San Martino Policlinico Hospital, IRCCS for Oncology and Neuroscience, Genoa, Italy; Jordi Mancebo, Servei de Medicina Intensiva, Hospital de Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain; Robert Stevens, Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; Geert Meyfroidt, Department and Laboratory of Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospitals Leuven and KU Leuven, Herestraat 49, Box 7003 63, 3000 Leuven, Belgium; Rafael Badenes Department of Anesthesiology and Surgical-Trauma Intensive Care, Hospital Clinic Universitari de Valencia, Department of Surgery, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain Valentina Della Torre, Intensive Care Unit, St Mary’s Hospital, London, UK Raimund Helbok Department of Neurology, Neurological Intensive Care Unit, Medical University of Innsbruck, Anichstrasse 35, 6020, Innsbruck, Austria. Jose’ Suarez Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD Nino Stocchetti Department of Physiopathology and Transplantation, Milan University, Milan, Italy; Neuro Intensive Care Unit, Fondazione Erasmus Medical Center, Ca Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milano, Milan, Italy Marcelo Gama De Abreu Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Pulmonary Engineering Group, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus at the Technische Universität Dresden, Fetscherstr. 74, 01307, Dresden, Germany. Marcus Schultz Department of Intensive Care Medicine and Laboratory of Experimental Intensive Care and Anesthesiology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Raphael Cinotti Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Hôpital Guillaume et René Laennec, University Hospital of Nantes, Saint-Herblain, France Louis Blanch Critical Care Center, Institut d'Investigació i Innovació Parc Taulí I3PT, Hospital Universitarí Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Spain. lblanch@tauli.cat. Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES), Instituto de Salúd Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. Karim Asehnoune Department of Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Hôtel Dieu, University Hospital of Nantes, Nantes, France Christian Putensen Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University Clinical Center Bonn, Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany John Laffey School of Medicine, National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG), Galway, Ireland

Contributors: CR, GC, FT and PP were equally responsible for writing ofthe manuscript and participated in study design. CR drafted the first version of the manuscript. FT, PP, GC, SG, PR and AV reviewed the manuscript and agreed with submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

VENTIBRAIN:

Maura Mandelli, Jordi Mancebo, Robert Stevens, Geert Meyfroidt, Rafael Badenes, Valentina Della Torre, Raimund Helbok, Jose’ Suarez, Nino Stocchetti, Marcelo Gama De Abreu, Marcus Schultz, Raphael Cinotti, Louis Blanch, Karim Asehnoune, Christian Putensen, and John Laffey

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Borsellino B, Schultz MJ, Gama de Abreu M, et al. Mechanical ventilation in neurocritical care patients: a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10:1123–32. 10.1080/17476348.2017.1235976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slutsky AS. Lung injury caused by mechanical ventilation. Chest 1999;116:9S–15. 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.9S-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robba C, Bonatti G, Battaglini D, et al. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute ischaemic stroke: from pathophysiology to clinical practice. Crit Care 2019;23:388. 10.1186/s13054-019-2662-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samary CS, Ramos AB, Maia LA, et al. Focal ischemic stroke leads to lung injury and reduces alveolar macrophage phagocytic capability in rats. Crit Care 2018;22:249. 10.1186/s13054-018-2164-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heuer JF, Pelosi P, Hermann P, et al. Acute effects of intracranial hypertension and ARDS on pulmonary and neuronal damage: a randomized experimental study in pigs. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:1182–91. 10.1007/s00134-011-2232-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Putensen C, Theuerkauf N, Zinserling J, et al. Meta-analysis: ventilation strategies and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:566–76. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-8-200910200-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saddy F, Sutherasan Y, Rocco PRM, et al. Ventilator-Associated lung injury during assisted mechanical ventilation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2014;35:409–17. 10.1055/s-0034-1382153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO, et al. Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:170–7. 10.1164/rccm.200706-893OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2731–40. 10.1172/JCI60331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e2124. 10.1136/bmj.e2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sage M, See W, Nault S, et al. Effect of low versus high Tidal-Volume total liquid ventilation on pulmonary inflammation. Front Physiol 2020;11:603. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580–637. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Determann RM, Royakkers A, Wolthuis EK, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with conventional tidal volumes for patients without acute lung injury: a preventive randomized controlled trial. Crit Care 2010;14:R1. 10.1186/cc8230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, et al. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;308:1651–9. 10.1001/jama.2012.13730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens RD, Lazaridis C, Chalela JA. The role of mechanical ventilation in acute brain injury. Neurol Clin 2008;26:543–63. 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cinotti R, Bouras M, Roquilly A, et al. Management and weaning from mechanical ventilation in neurologic patients. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:381. 10.21037/atm.2018.08.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Della Torre V, Badenes R, Corradi F, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in traumatic brain injury: how do we manage it? J Thorac Dis 2017;9:5368–81. 10.21037/jtd.2017.11.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robba C, Poole D, McNett M, et al. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: recommendations of the European Society of intensive care medicine consensus. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:2397–410. 10.1007/s00134-020-06283-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow outcome scale and the extended Glasgow outcome scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma 1998;15:573–85. 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Citerio G, Prisco L, Oddo M, et al. International prospective observational study on intracranial pressure in intensive care (ICU): the SYNAPSE-ICU study protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026552. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frisvold SK, Robba C, Guérin C. What respiratory targets should be recommended in patients with brain injury and respiratory failure? Intensive Care Med 2019;45:683–6. 10.1007/s00134-019-05556-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelosi P, Ferguson ND, Frutos-Vivar F, et al. Management and outcome of mechanically ventilated neurologic patients. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1482–92. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821209a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koutsoukou A, Perraki H, Raftopoulou A, et al. Respiratory mechanics in brain-damaged patients. Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1947–54. 10.1007/s00134-006-0406-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nortje J, Coles JP, Timofeev I, et al. Effect of hyperoxia on regional oxygenation and metabolism after severe traumatic brain injury: preliminary findings. Crit Care Med 2008;36:273–81. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000292014.60835.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawryluk GWJ, Aguilera S, Buki A, et al. A management algorithm for patients with intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle international severe traumatic brain injury consensus conference (SIBICC). Intensive Care Med 2019;45:1783–94. 10.1007/s00134-019-05805-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carney N, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, fourth edition. Neurosurgery 2017;80:6–15. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karalapillai D, Weinberg L, Peyton P, et al. Effect of intraoperative low tidal volume vs conventional tidal volume on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing major surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:848–58. 10.1001/jama.2020.12866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serpa Neto A, Simonis FD, Barbas CSV, et al. Association between tidal volume size, duration of ventilation, and sedation needs in patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:950–7. 10.1007/s00134-014-3318-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caricato A, Conti G, Della Corte F, et al. Effects of PEEP on the intracranial system of patients with head injury and subarachnoid hemorrhage: the role of respiratory system compliance. J Trauma 2005;58:571–6. 10.1097/01.TA.0000152806.19198.DB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robba C, Ortu A, Bilotta F, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory distress syndrome in trauma patients: a case series and systematic literature review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82:165–73. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tejerina E, Pelosi P, Muriel A, et al. Association between ventilatory settings and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients due to brain injury. J Crit Care 2017;38:341–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neto AS, Barbas CSV, Simonis FD, et al. Epidemiological characteristics, practice of ventilation, and clinical outcome in patients at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units from 16 countries (PRoVENT): an international, multicentre, prospective study. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4:882–93. 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30305-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33., Simonis FD, Serpa Neto A, et al. , Writing Group for the PReVENT Investigators . Effect of a low vs intermediate tidal volume strategy on ventilator-free days in intensive care unit patients without ARDS: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;320:1872–80. 10.1001/jama.2018.14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SNT, Barbas CSV, et al. Protective versus conventional ventilation for surgery: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2015;123:66–78. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.