Abstract

Context

In spring 2020, schools closed to in-person teaching and sports were cancelled to control the transmission of COVID-19. The changes that affected the physical and mental health among young athletes during this time remain unknown.

Objective

To identify changes in the health (mental health, physical activity, and quality of life) of athletes that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Sample recruited via social media.

Patients or Other Participants

A total of 3243 Wisconsin adolescent athletes (age = 16.2 ± 1.2 years, 58% female) were surveyed in May 2020 (During COVID-19). Measures for this cohort were compared with previously reported data for Wisconsin adolescent athletes (n = 5231; age = 15.7 ± 1.2 years, 47% female) collected in 2016 to 2018 (PreCOVID-19).

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Demographic information included sex, grade, and sport(s) played. Health assessments included the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item to identify depression symptoms, the Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale to gauge physical activity, and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 to evaluate health-related quality of life. Univariable comparisons of these variables between groups were conducted via t or χ2 tests. Means and 95% CIs for each group were estimated using survey-weighted analysis-of-variance models.

Results

Compared with preCOVID-19 participants, a larger proportion of During COVID-19 participants reported moderate to severe levels of depression (9.7% versus 32.9%, P < .001). Scores of the During COVID-19 participants were 50% lower (worse) on the Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale (mean [95% CI] = 12.2 [11.9, 12.5] versus 24.7 [24.5, 24.9], P < .001) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 compared with the PreCOVID-19 participants (78.4 [78.0, 78.8] versus 90.9 [90.5, 91.3], P < .001).

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescent athletes described increased symptoms of depression, decreased physical activity, and decreased quality of life compared with adolescent athletes in previous years.

Keywords: depression, mental health, physical activity, high school athletes, public health

Key Points

During the COVID-19 pandemic, adolescent athletes were 3 times more likely to report moderate to severe symptoms of depression than those from whom data were collected before COVID-19.

Adolescent athletes' scores for physical activity and quality of life were lower during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with those of high school athletes assessed several years earlier.

Post–COVID-19 policies should be implemented to improve the health of US adolescent athletes.

An estimated 8.4 million US high school students participate in interscholastic athletics.1 Adolescent sport participation is recognized as having profound positive influences on the health and well-being of students, as evidenced by higher levels of academic achievement and healthy physical activity and lower levels of anxiety and depression than in students who did not participate in athletics.2–5 Additionally, high school sport participation is one of the most important factors for lifelong physical activity and health.6–12

During the winter and spring of 2020, COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, reached pandemic proportions throughout the world. Across the United States, schools were closed and athletic seasons were cancelled to slow the spread of the disease. Experts13–17 suggested that the efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 may have profound societal, economic, and psychosocial consequences for students and need to be further examined.

In a recent study,18 female athletes, athletes in grade 12, team sport participants, and athletes from areas with a higher percentage of the population under age 18 living in poverty reported lower levels of physical activity, greater symptoms of anxiety and depression, and lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in May 2020 during the nationwide shutdown. Describing the prevalence of mental health disorders during the COVID-19–related restrictions is useful but does not fully address how specific athletic populations have been affected. We are not aware of researchers to date who have specifically documented the mental and physical health changes in adolescent athletes during the pandemic. Quantifying these changes will allow health care providers to implement strategies to improve the health of adolescent athletes moving forward.19

An estimated 93 000 (33%) of the 284 000 Wisconsin high school students compete in interscholastic sports each year.1 At the start of the 2019–2020 school year, 478 Wisconsin schools offered interscholastic athletics and fielded teams that competed in 15 to 20 sports.20

These student-athletes typically competed on 1 to 3 athletic teams throughout the school year (fall, winter, and spring sport seasons), but many also continued to train with their teammates when their sport was not in season.21,22 More than half of these student-athletes also competed on club sport teams not affiliated with their school during the academic year.23,24

In March 2020, Wisconsin government and health officials mandated a 2-week statewide school closure to slow the spread of COVID-19. The closure order was eventually extended twice to run through the end of the school year.25 High school students' academic work moved online and all in-person teaching and interscholastic athletics for students in grades 9 through 12 were cancelled. Additionally, adolescent club sport teams were restricted from participating during this time. Although necessary to slow the community spread of the virus, these COVID-19 mitigation strategies may nonetheless have had negative effects on the mental and physical health of adolescents.26

Quantifying the changes to the health of adolescent athletes that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic is critical to understanding their effects on athletes in order to improve management in the future.27–29 This information will allow sports medicine providers, school administrators, and health care policy experts to implement strategies to improve the short-term and long-term mental and physical health of adolescent athletes in the months and years to come as we transition from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The purpose of our study was to measure changes in the mental and physical health of Wisconsin adolescent athletes manifested during the COVID-19–related school closures and sport cancellations. To measure these changes, we compared athlete self-report data on depression, physical activity, and HRQoL that we collected in May 2020 (During COVID-19) with Wisconsin data from investigations22,30–33 carried out by the study team during normal high school sport operations in the years 2015 to 2018 (PreCOVID-19).

We hypothesized that adolescent student-athletes would report worse mental health, as well as lower physical activity and HRQOL scores, during the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown than before COVID-19.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board in April 2020. Wisconsin adolescent athletes (males and females, grade = 9–12, age = 13–19 years) were recruited via social media (Facebook, Twitter) for the study via an anonymous online survey in May 2020. To ensure widespread distribution and recruitment for the study, we supplied the social media links to sports medicine provider colleagues across Wisconsin and in the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association and Wisconsin Athletic Trainers' Association, who forwarded the links to high school athletes throughout the state.

The 69-item survey consisted of a section on participant demographics followed by 3 segments that contained validated instruments used to measure mental health, physical activity, and HRQoL in adolescents. Demographic information requested was age, grade, school size, school funding (private or public), and zip code, as well as a list of all the high school and club (not affiliated with the participant's school) sports in which he or she had competed during the previous 12 months.

Mental Health

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item (PHQ-9) survey was used to evaluate depression symptoms. This 9-item questionnaire asks participants to rate the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks.34 Scores on the PHQ-9 range from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating a greater level of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for depression screening in adolescent patients aged 13 to 17 years. In addition to the total score, PHQ-9 categorical scores of 0 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, and ≥20 correspond to minimal or none, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression symptoms, respectively.35,36

Physical Activity

Physical activity level was assessed with the Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale (PFABS).37,38 This validated 8-item instrument was designed to measure the physical activity of children aged 10 to 18 years during the preceding month. Scores range from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating greater physical activity.37,38

Health-Related Quality of Life

Health-related quality of life was measured with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 (PedsQL). The 23-item PedsQL questionnaire assesses HRQoL during the previous 7 days. The PedsQL has been validated for use in children aged 2 to 18 years.39,40 Physical and psychosocial subscale scores, as well as the total score, range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater HRQoL. The PedsQL survey has been used to measure HRQoL in samples of healthy and injured adolescent athletes.41

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed on data from participants who completed the survey. Participants were excluded if they did not complete the entire survey, were not in grades 9 through 12, or indicated they had not been active in club or interscholastic sports in the previous 12 months.

Demographic variables and individual sport participation were summarized (mean ± SD or No. [%]) overall and by study group (PreCOVID-19 and During COVID-19 athlete cohorts) stratified by sex. Univariable comparisons of these variables between groups were conducted via t tests or χ2 tests. We estimated means and 95% CIs for each group using survey-weighted analysis-of-variance models separately for the depression, physical activity, and quality-of-life measures. A weighted ordinal logistic regression model was calculated to estimate the percentages of depression level (PHQ-9) for each group. A group-by-sex interaction was modeled for all sex-specific estimates. In addition, because grade level is highly correlated with age, we chose to adjust for age and sex in our models and evaluated group and sex interactions as appropriate.

Sample survey weights were derived based on sport and sex using the 2018–2019 Wisconsin high school sport participation statistics compiled annually by the National Federation of High Schools.1 The May 2020 PHQ9, PFABS, and PedsQL scores were compared with historical data of Wisconsin adolescent athletes collected during normal school operations in the years 2015 to 2018.19,26–29 Although it would have been ideal to have the PreCOVID-19 and During COVID-19 samples drawn from the same individual athletes, this option was not available to us, as all in-person research participant recruitment was prohibited because of pandemic-related restrictions in May 2020. However, the methods we used allowed us to capture data from a large number of Wisconsin athletes that we believed constituted a representative statewide sample. We also recognize that the 2 groups may have had systematic differences, which often occurs in nonrandomized observational studies whose authors seek to document the changes in mental health among various populations. The methods we used were similar to those used in multiple prior investigations42–44 from various countries documenting the changes in mental health among various populations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To allow for meaningful comparisons between the groups, we weighted the analyses based on inverse propensity score weights (IPSWs), which is an accepted method for drawing meaningful comparisons between groups with important characteristic differences.45 The addition of the IPSWs to the final models adjusts for the characteristic differences between the groups to allow for statistical comparisons. Propensity score weights were assigned using a logistic regression that was weighted based on the sample survey weights. The survey weights for multiple-sport athletes were based on the most common sport played. Further, we are not aware of evidence to support the idea that athletes participating in a specific sport scores were significantly different from athletes participating in other sports; much of the literature shows that QoL may differ based on sex (male versus female) or being classified as an athlete or nonathlete rather than on the type of sport participation.40,41 As a result, we included high school individual sport status as a covariate in our models. Group assignment was the dependent variable, and age, sex, and high school individual sport status were predictor variables. Final models comparing the During COVID-19 group with the PreCOVID-19 group included weights as the multiplication of the sampling weights and IPSWs.46

RESULTS

A total of 3243 Wisconsin adolescent athletes (age = 16.2 ± 1.2 years, females = 58%) completed the survey in May 2020 (During COVID-19), and responses were obtained from participants residing in 71 of the 72 counties in Wisconsin (99%). Because of the convenience-sampling design, information regarding the response rate was unavailable. A total of 2730 participants (84%) indicated they attended a publicly funded school; the median (interquartile range) school enrollment was 802 (range = 401–1248). Nine hundred seventy (29.9%) had competed in a single sport and the remaining 2273 (70.1%) had competed in 2 or more sports for their school in the prior 12 months. The During COVID-19 participants were most likely to have competed in track (32.8%), basketball (29.1%), and volleyball (21.2%). In addition to competing for their high school teams, 1962 (60.5%) had competed as an individual or as part of a club team outside their school setting.

The PreCOVID-19 cohort consisted of 5231 athletes (age = 15.7 ± 1.2 years, females = 65%) who were enrolled in cohort and longitudinal studies in 2015 to 2018.22,30–33 The PreCOVID-19 participants resided in 56 Wisconsin counties (78%). A total of 4399 (84%) attended a publicly funded school; the median (interquartile range) school enrollment was 654 (range = 299–1017). The PreCOVID-19 participants were most likely to have competed in volleyball (55.7%), basketball (43.2%), and football (23.3%). A summary of the number of athletes and percentages of the sports played for both the During COVID-19 and PreCOVID-19 cohorts is in the Supplementary Table.

Mental Health

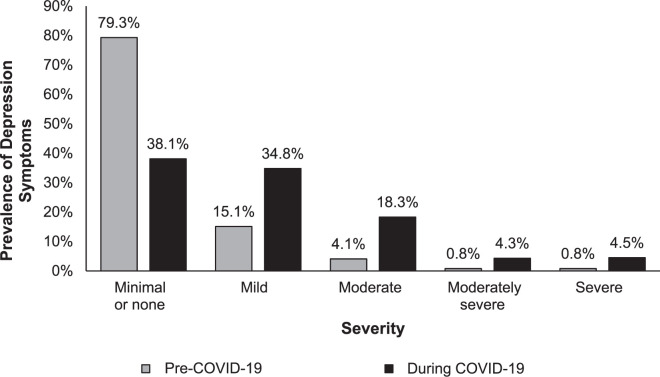

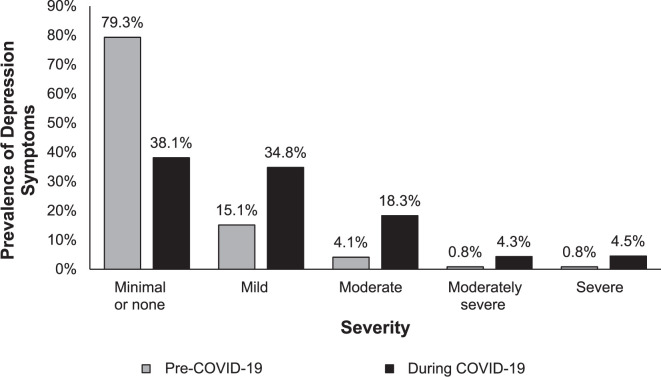

The proportion of females who described a mild level of depression in the During COVID-19 athletes was 43% higher compared with the PreCOVID-19 females (During COVID-19 = 35%, PreCOVID-19 = 24%, P < .001). Females in the During COVID-19 group reported a 3-fold increase in moderate, moderately severe, or severe levels of depression versus the PreCOVID-19 athletes (During COVID-19 = 37%, PreCOVID-19 = 11%, P < .001). The prevalence of depression levels for females in both the PreCOVID-19 and During COVID-19 groups is shown in Figure 1. The proportion of males in the During COVID-19 group who demonstrated a mild level of depression was 130% higher compared with PreCOVID-19 males (During COVID-19 = 35%, PreCOVID-19 = 15%, P < .001). The proportion of males in the During COVID-19 group who reported moderate, moderately severe, or severe levels of depression was 4.5 times higher than among males in the PreCOVID-19 group (During COVID-19 = 27%, PreCOVID-19 = 6%, P < .001). The prevalence of depression levels for males in the During COVID-19 and PreCOVID-19 group is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of depression symptoms for female adolescent athletes before the COVID-19 pandemic (Pre-COVID-19) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (During COVID-19).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of depression symptoms for male adolescent athletes before the COVID-19 pandemic (Pre-COVID-19) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (During COVID-19).

Overall, PHQ-9 scores for the During COVID-19 athletes were 2.5 times higher (worse) than for those in the PreCOVID-19 group. The During COVID-19 females demonstrated a PHQ-9 score (mean [95% CI]) that was more than twice the PHQ-9 score for females in the PreCOVID-19 group (8.2 [7.9, 8.5] versus 3.6 [3.4, 3.8]). Similarly, the During COVID-19 males had PHQ-9 scores that were 3 times higher than those of the males in the PreCOVID-19 group (7.8 [7.5, 8.1] versus 2.6 [2.2, 2.9]). The PHQ-9 scores for both groups are found in the Table.

Table.

Depression, Physical Activity, and Health-Related Quality-of-Life Scores for Adolescent Athletes Before (PreCOVID-19) and During the COVID-19 Pandemic (During COVID-19)

| Variable |

All Participants |

Females |

Males |

||||||

| Pre-COVID-19 (n = 5231) |

During COVID-19 (n = 3243) |

P Value |

Pre-COVID-19 (n = 3402) |

During COVID-19 (n = 1877) |

P Value |

Pre-COVID-19 (n = 1829) |

During COVID-19 (n = 1366) |

P Value |

|

| Sex, male, No. (%) | 1829 (35.0) | 1366 (42.1) | <.001 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 15.7 ± 1.1 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | <.001 | 15.6 ± 1.1 | 16.1 ± 1.2 | <.001 | 15.8 ± 1.2 | 16.2 ± 1.2 | <.001 |

| Grade, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | .003 | ||||||

| 9 | 1763 (33.7) | 862 (26.6) | 1177 (34.6 | 499 (26.6) | 586 (32.0) | 363 (26.6) | |||

| 10 | 1388 (26.5) | 845 (26.1) | 937 (27.5) | 509 (27.1) | 451 (24.7) | 336 (24.6) | |||

| 11 | 1153 (22.0) | 848 (26.1) | 720 (21.2) | 470 (25.0) | 433 (23.7) | 378 (27.7) | |||

| 12 | 927 (17.7) | 688 (21.2) | 568 (16.7) | 399 (21.3) | 359 (19.6) | 289 (21.2) | |||

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item total scorea | 3.3 (3.1, 3.5) | 8.0 (7.8, 8.2) | <.001 | 3.6 (3.4, 3.8) | 8.2 (7.9, 8.5) | <.001 | 2.6 (2.2, 2.9) | 7.8 (7.5, 8.1) | <.001 |

| Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale total scoreb | 24.7 (24.5, 24.9) | 12.2 (11.9, 12.5) | <.001 | 24.5 (24.2, 24.7) | 11.4 (11.1, 11.8) | <.001 | 25.7 (25.3, 26.1) | 13.9 (13.4, 14.4) | <.001 |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4c | |||||||||

| Physical summary | 91.7 (91.3, 92.1) | 82.6 (82.2, 83.0) | <.001 | 89.6 (89.1, 90.0) | 80.9 (80.5, 81.4) | <.001 | 96.6 (95.9, 97.3) | 86.1 (85.4, 86.8) | <.001 |

| Psychosocial summary | 90.4 (89.9, 90.8) | 76.2 (75.8. 76.6) | <.001 | 90.1 (89.6, 90.6) | 75.0 (74.5, 75.5) | <.001 | 90.9 (90.2, 91.7) | 78.6 (77.9, 79.3) | <.001 |

| Totald | 90.9 (90.5, 91.3) | 78.4 (78.0, 78.8) | <.001 | 90.0 (89.5, 90.4) | 77.1 (76.6, 77.6) | <.001 | 92.9 (92.2, 93.6) | 81.2 (80.6, 81.9) | <.001 |

Historical group n = 2156.

Historical group n = 1002.

Historical group n = 5231.

Total score was reported as the sample weight × inverse propensity score weighted mean (95% CI).

Physical Activity

The total PFABS scores (mean [95% CI]) were lower (ie, less physical activity) for the During COVID-19 group compared with the PreCOVID-19 group (12.2 [11.9, 12.5] versus 24.7 [24.5, 24.9], P < .001). The During COVID-19 females displayed PFABS scores that were more than 50% lower (ie, worse) than those of the PreCOVID-19 females (11.4 [11.1, 11.8] versus 24.5 [24.2, 24.7], P < .001). Similarly, for males in the During COVID-19 group, PFABS scores were approximately 50% lower than in the PreCOVID-19 group (13.9 [13.4, 14.4] versus 25.7 [25.3, 26.1], P < .001). The PFABS scores for both groups are available in the Table.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Higher (ie, better) PedsQL physical summary, psychosocial summary, and PedsQL total scores were evident for athletes in the PreCOVID-19 group compared with those in the During COVID-19 group (P < .001). For females, the PreCOVID-19 physical health summary scores (mean [95% CI]) were 11% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (89.6 [89.1, 90.0] versus 80.9 [80.5, 81.4], P < .001). Similarly, for females, the PreCOVID-19 psychosocial health summary scores were 20% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (90.1 [89.6, 90.6] versus 75.0 [74.5, 75.5], P < .001), and the PreCOVID-19 total PedsQL scores for females were 17% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (90.0 [89.5, 90.4] versus 77.1 [76.6, 77.6], P < .001).

For males, the PreCOVID-19 physical health summary scores (mean [95% CI]) were 12% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (96.6 [95.9, 97.3] versus 86.1 [85.4, 86.8], P < .001). Similarly, for males, the PreCOVID-19 psychosocial health summary scores were 14% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (90.9 [90.2, 91.7] versus 78.6 [77.9, 79.3], P < .001). The males' PedsQL total scores in the PreCOVID-19 group were also 14% higher than those in the During COVID-19 group (92.9 [92.2, 93.6] versus 81.2 [80.6, 81.9], P < .001). The PedsQL scores for both groups are shown in the Table.

DISCUSSION

Our primary findings were that the mental health, physical activity, and HRQoL scores for adolescent athletes were worse during the COVID-19 pandemic than scores reported by adolescent athletes in prior years. To our knowledge, no existing data demonstrated mental health, physical activity, and HRQoL changes for adolescent athletes immediately after the cancellation of school and athletic seasons during the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been suggested that the negative psychosocial effects of COVID-19–related mitigation measures may manifest in additional health care utilization and spending in the coming months and years.19,26 These results can be used to inform stakeholders of the potential negative consequences of quarantine restrictions. Further, we feel these data can drive informed discussions regarding the reinitiation or continuation of sports for adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental Health

The levels of depressive symptoms and total symptom scores (as measured by the PHQ-9) reported in the During COVID-19 cohort were higher than those of our PreCOVID-19 athletes. The During COVID-19 cohort had more depressive symptoms than in a previous study48 that indicated approximately 2% of adolescents had severe depressive symptoms. Specific to athletic populations, the During COVID-19 cohort had more depressive symptoms than seen in earlier research48,49 involving adolescent athletes, which revealed depression and anxiety symptoms that ranged from 2% to 10%. Although the prevalence of moderate to severe depressive symptoms was greater among females than males in the During COVID-19 group, both sexes demonstrated dramatically higher rates compared with data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic.47–49 Thus, a significant mental health burden was displayed by the During COVID-19 group.

The decrease in mental health is multifaceted and complex and may be related to reduced socialization, increased family strain, and less access to support services.50 In Wisconsin, many families self-isolated or severely limited social contact for several weeks to several months in spring 2020. Previous authors50,51 determined that quarantines negatively affected mental health. Schools play an important role in providing access to mental health services for disadvantaged populations, and health care providers, parents, and policy makers should be mindful of the mental health strain the current pandemic is placing on adolescents.52

Physical Activity

Our study is the first in the United States to demonstrate a decrease in physical activity levels in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although male athletes described slightly higher levels of physical activity than females, the decrease in both sexes during the COVID-19 restrictions was similar, with current levels of physical activity approximately 50% lower than those reported by Fabricant et al37 in a similar population before COVID-19. Physical activity is known to have beneficial effects on a wide range of health outcomes in adolescents, including sleep, academic success, wellbeing, and mental health.53–55 Therefore, the identified decrease in mental health among our participants may be at least partly due to the removal of the positive effects that physical activity provides to adolescents.

Childhood obesity was a health care crisis before the COVID-19 pandemic that is increasing in the United States and projected to become worse because of the pandemic.28,29,56 Decreased physical activity and increased stress may increase the risk of severe COVID-19 cases in obese children.29 Decreased physical activity in adolescents may also have long-term negative effects and implications in terms of increased risks for obesity and cardiometabolic disease if these levels remain low for prolonged periods.57 Chronically low levels of physical activity may also compound the mental health consequences of the current crisis.53,54 Further, evidence indicated that sport participation during high school was related to improved health and wellbeing throughout adulthood.7–11 As the time spent being physically active during the school day has decreased, organized sports have been proposed as a means of stabilizing long-term physical activity in adolescents and improving adult physical activity.51 Though returning adolescents to organized sports is complex and requires careful consideration, stakeholders should consider the promotion of physical activity a top priority during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Several authors41,58,59 have shown that individuals with increased physical activity, interscholastic sport participation, or both had higher HRQoL scores than inactive adolescents and high school nonathletes. Thus, it is not surprising that HRQoL scores were lower in the During COVID-19 cohort compared with the PreCOVID-19 athletes. Interestingly, the overall PedsQL scores observed for the During COVID-19 athletes were similar to those recorded in the general adolescent population but higher than those in adolescents with chronic diseases.39,60

In our study, females displayed higher levels of depressive symptoms as well as less physical activity and lower HRQoL scores than males. These findings were consistent with earlier research35–39,52,54,58 on depression, physical activity, and HRQoL in adolescents. Therefore, it is unlikely that the sex differences in depressive symptoms and HRQoL scores we noted are directly attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, we found dramatic reductions in HRQoL for both males and females during the COVID-19 shutdown, and investigators should continue to monitor HRQoL in adolescents as separation from peers and sports continues during the restrictions initiated to limit the spread of COVID-19. This information may help facilitate early identification of decreases in quality of life in adolescents that can alert parents, teachers, and health care providers to initiate intervention programs to support these adolescents.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the data were self-reported from online surveys and not the result of a clinical examination conducted by a health care provider. However, our results include data from a large sample of athletes and align with reports from experts13,16,17,19,26 who stated that COVID-19 would affect the health of youth populations. Second, we acknowledge a possible response bias among participants. We cannot know for certain if the sample represented all Wisconsin adolescent athletes or was biased toward athletes who were more likely to respond if they experienced the most profound effects on their health. Third, because of the survey delivery method, our sample may have been biased toward athletes whose families were of higher socioeconomic status, with easy access to internet services and social media platforms. We could not eliminate this bias, but we did collect results from 99% of Wisconsin counties, which spanned a wide range of socioeconomic levels. Further, we called on medical colleagues as well as the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association and Wisconsin Athletic Trainers' Association to publicize the study and urge all adolescent athletes to participate. In addition, we used recent high school sport participation statistics from Wisconsin schools to calculate sample weights in order to mitigate the possible effects of selection bias. This increased the representativeness of our results with regard to the entire adolescent athlete population in Wisconsin. Still, we acknowledge that, although the results were representative of Wisconsin adolescent athletes, they may not be generalizable to all US adolescent athletes. Another potential limitation may be that the PreCOVID-19 participants reported data at the beginning of their respective (fall, winter, or spring) sport seasons, whereas the During COVID-19 participants reported data in the spring. Although this timing may have affected the scores of the groups, we located no evidence in the current literature that indicated the time of year or whether the athlete was in or out of the sport season would affect self-reported scores. Additionally, it is possible that other variables, such as involvement in other cocurricular activities and missing school-related events, were not accounted for in our work and could have confounded the results. Finally, we did not include a control group of nonathletes. Our existing data sets provided information only on athletes; therefore, we could address changes over time (PreCOVID-19 to During COVID-19) only in athletic populations. We recognize that the effects observed in this sample of athletes would likely be seen across a wide spectrum of youth because of the cancellations of most extracurricular activities.

CONCLUSIONS

The physical activity and mental health of adolescent athletes worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with PreCOVID-19 values. Our findings suggest that adolescent athletes experienced dramatic increases in symptoms of depression along with decreases in physical activity and HRQoL during this time. Sports medicine and health policy experts should consider the possible negative mental and physical health effects that may have become prevalent among adolescent athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic, and stakeholders should develop systematic interventions that can be implemented to reduce these negative changes in the months and years to come.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Participation in school athletics. Child Trends. 2020 Accessed July 12. https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/participation-in-school-athletics.

- 2.Bailey R. Physical education and sport in schools: a review of benefits and outcomes. J Sch Health. 2006;76(8):397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(98) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould D, Flett R, Lauer L. The relationship between psychosocial developmental and the sports climate experienced by underserved youth. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison PA, Narayan G. Differences in behavior, psychological factors, and environmental factors associated with participation in school sports and other activities in adolescence. J Sch Health. 2003;73(3):113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques A, Ekelund U, Sardinha LB. Associations between organized sports participation and objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time and weight status in youth. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(2):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashdown-Franks G, Sabiston CM, Solomon-Krakus S, O'Loughlin JL. Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Ment Health Phys Act. 2017;12:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dohle S, Wansink B. Fit in 50 years: participation in high school sports best predicts one's physical activity after age 70. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Easterlin MC, Chung PJ, Leng M, Dudovitz R. Association of team sports participation with long-term mental health outcomes among individuals exposed to adverse childhood experiences. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):673–681. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan KM, Thompson AM, Blair SN, et al. Sport and exercise as contributors to the health of nations. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):59–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kniffin KM, Wansink B, Shimizu M. Sports at work: anticipated and persistent correlates of participation in high school athletics. J Leadersh Organ Stud. 2015;22(2):217–230. doi: 10.1177/1548051814538099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troutman KP, Dufur MJ. From high school jocks to college grads: assessing the long-term effects of high school sport participation on females' educational attainment. Youth Soc. 2007;38(4):443–462. doi: 10.1177/0044118X06290651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):819–820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christakis DA. School reopening—the pandemic issue that is not getting its due. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(10):928. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czeisler ME, Lane RI, Petrosky et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(32):1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Fitz-Henley J., II COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020007294. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuine TA, Biese KM, Petrovska L, et al. Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life of US adolescent athletes during COVID-19–related school closures and sport cancellations: a study of 13 000 athletes. J Athl Train. 2021;56(1):11–19. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0478.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajapakse N, Dixit D. Human and novel coronavirus infections in children: a review. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2021;41(1):36–55. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2020.1781356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association. 2020 Accessed May 12. https://www.wiaawi.org/

- 21.McGuine TA, Post EG, Hetzel S, Brooks MA, Bell D. A prospective study on the impact of sport specialization on lower extremity injury rates in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2706–2712. doi: 10.1177/0363546517710213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuine TA, Pfaller AY, Kliethermes SA, et al. The effect of sport related concussion injuries on concussion symptoms and health-related quality of life in male and female adolescent athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(14):3514–3520. doi: 10.1177/0363546519880175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell DR, Post EG, Trigsted SM, et al. Sport specialization characteristics between rural and suburban high school athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(1):2325967117751386. doi: 10.1177/2325967117751386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Post EG, Bell DR, Trigsted SM, et al. Association of volume, club sports, and specialization with injury history in youth athletes. Sports Health. 2017;9(6):518–523. doi: 10.1177/1941738117714160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emergency Order #12 Safer at Home Order. 2020 State of Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Accessed May 12. https://evers.wi.gov/Documents/COVID19/EMO12-SaferAtHome.pdf.

- 26.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Considerations for school-related public health measures in the context of COVID-19: annex to considerations in adjusting public health and social measures in the context of COVID-19. World Health Organization. 2020 Published September 14. Accessed April 15, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/considerations-for-school-related-public-health-measures-in-the-context-of-covid-19.

- 28.An R. Projecting the impact of the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic on childhood obesity in the United States: a microsimulation model. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(4):302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browne NT, Snethen JA, Greenberg CS, et al. When pandemics collide: the impact of COVID-19 on childhood obesity. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;56:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donovan L, Hetzel S, Laufenberg CR, McGuine TA. Prevalence and impact of chronic ankle instability in adolescent athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(2):2325967119900962. doi: 10.1177/2325967119900962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuine TA, Pfaller A, Hetzel S, Broglio SP, Hammer E. A prospective study of concussions and health outcomes in high school football players. J Athl Train. 2020;55(10):1013–1019. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-141-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammer E, Hetzel S, Pfaller A, McGuine T. Longitudinal assessment of depressive symptoms after sport-related concussion in a cohort of high school athletes. Sports Health. 2021;13(1):31–36. doi: 10.1177/1941738120938010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGuine TA, Post E, Biese KM, et al. The incidence and risk factors for injuries in girls volleyball: a prospective study of 2072 players. J Athl Train. 2020 doi: 10.4085/182-20. Accepted manuscript. Published online November 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Andrews JH, Cho E, Tugendrajch SK, Marriott BR, Hawley KM. Evidence-based assessment tools for common mental health problems: a practical guide for school settings. Child Sch. 2020;42(1):41–52. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdz024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z, et al. Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale: initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(6):716–727. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117–1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabricant PD, Robles A, Downey-Zayas T, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric sports activity rating scale: the Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale. HSS Pedi-FABS), editor. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2421–2429. doi: 10.1177/0363546513496548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabricant PD, Robles A, McLaren SH, Marx RG, Widmann RF, Green DW. Hospital for Special Surgery Pediatric Functional Activity Brief Scale predicts physical fitness testing performance. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1610–1616. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3429-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam KC, Valier AR, Bay RC, McLeod TC. A unique patient population? Health-related quality of life in adolescent athletes versus general, healthy adolescent individuals. J Athl Train. 2013;48(2):233–241. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niedzwiedz CL, Green MJ, Benzeval M, et al. Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of the UK Household Longitudinal Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(3):224–231. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan WY. Sampling distributions and robustness of t F and variance-ratio in two samples and ANOVA models with respect to departure from normality. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 1982;11(22):2485–2511. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ridgeway G, Kovalchik SA, Griffin BA, Kabeto MU. Propensity score analysis with survey weighted data. J Causal Inference. 2015;3(2):237–249. doi: 10.1515/jci-2014-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerber M, Best S, Meerstetter F, et al. Effects of stress and mental toughness on burnout and depressive symptoms: a prospective study with young elite athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(12):1200–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber S, Puta C, Lesinski M, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in young athletes using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Front Physiol. 2018;9:182. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ali MM, West K, Teich JL, Lynch S, Mutter R, Dubenitz J. Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. J Sch Health. 2019;89(5):393–401. doi: 10.1111/josh.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valkenborghs SR, Noetel M, Hillman CH, et al. The impact of physical activity on brain structure and function in youth: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20184032. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Biddle SJ, Ciaccioni S, Thomas G, Vergeer I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: an updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vella SA, Cliff DP, Magee CA, Okely AD. Associations between sports participation and psychological difficulties during childhood: a two-year follow up. J Sci Med Sport. 2015;18(3):304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173459. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood: a 21-year tracking study. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Houston MN, Hoch MC, Hoch JM. Health-related quality of life in athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Athl Train. 2016;51(6):442–453. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.7.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dahab K, Potter MN, Provance A, Albright J, Howell DR. Sport specialization, club sport participation, quality of life, and injury history among high school athletes. J Athl Train. 2019;54(10):1061–1066. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-361-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. Impaired health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic conditions: a comparative analysis of 10 disease clusters and 33 disease categories/severities utilizing the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.