Abstract

Congenital vaginal atresia is a rare congenital reproductive tract abnormality. To assess the clinical manifestations and feasibility of preserving uterus for congenital complete vaginal atresia with cervical aplasia, nineteen cases who underwent surgical treatment in West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University were retrospectively studied. The cervical status, clinical manifestations, the rate of vaginal re‐stenosis and pelvic inflammation after surgery were assessed. Additional 101 similar cases searched through digital Pub Med were included to analyze the feasibility of preserving the uterus. Periodic abdominal pain, primary amenorrhea, and pelvic mass were the primary signs and symptoms. According to the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), all the uterine cavities expanded, and the atresia sites were above the inner urethral orifice. Data of the cases preserving uteri from both our hospital and the literature showed the rate of re‐stenosis in patients with external cervical obstruction was 15.9% while it was 40% in the other types of cervical aplasia (P = .026). The rate of recurrent pelvic inflammation and hysterectomy was 2.3% for cervical external os obstruction and 8% for the other cervical aplasia types(P = .296). In conclusion, vaginoplasty and cervicovaginal anastomosis could preserve the fertility for complete vaginal atresia with cervical external os obstruction.

Keywords: cervical aplasia, cervicovaginal anastomosis, congenital complete vaginal atresia, tracheloplasty, vaginoplasty

1. INTRODUCTION

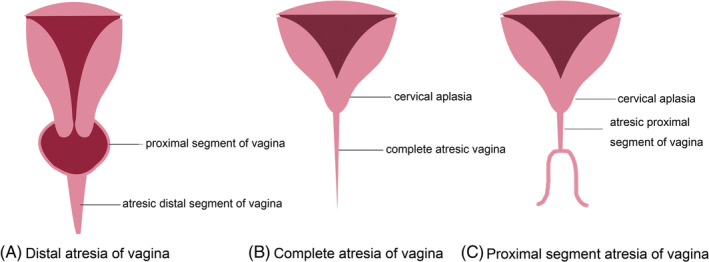

Congenital vaginal atresia is a rare congenital reproductive tract abnormality. Based on the American Fertility Society classification system(1988)1 and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and the European Society for Gynecological Endoscopy (ESGE) classification system 2 for female genital tract abnormalities, the congenital vaginal atresia is classified as complete and partial atresia. The Embryological‐clinical classification system3 further classifies this abnormality in complete and segmental type. According to Ruggeri's findings4, the “partial” or “segmental” atresia can be further divided into distal atresia and proximal atresia. Usually, the distal atresia with a normal proximal vagina has good outcomes following the distal tract's vaginoplasty, as it is much simpler, and the risk of vaginal stenosis is low.5 The complete and proximal atresia refers to the atresia of the total and upper segment of the vagina, which are usually accompanied by cervical malformations. (Figure 1). Because the proximal vaginal atresia is infrequent compared to complete atresia, herein, we only focused on the complete vaginal atresia.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of three types of congenital vaginal atresia

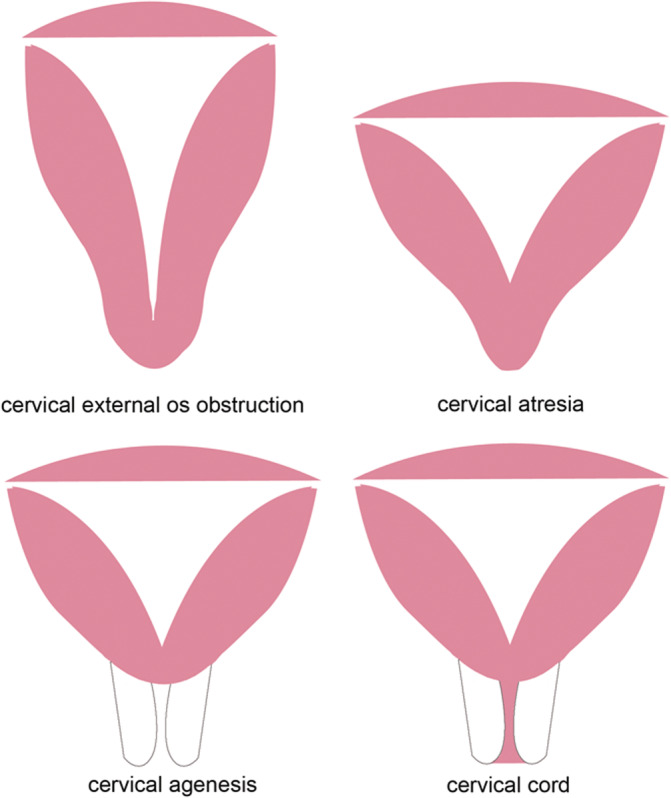

Hysterectomy and vaginoplasty are commonly used to treat complete vaginal atresia by preventing vaginal stenosis and pelvic inflammation. Nowadays, some gynecologists are trying to preserve the uterus and fertility via vaginoplasty and tracheloplasty in these types of cases. Xie et al 6 suggested that a cervical canal with a blind end could preserve the uterus through vaginal and cervical reconstruction. In addition, hysterectomy and vaginoplasty are recommended for patients with short or long solid cervix. According to the ESHRE/ESGE classification system2, cervical external os obstruction, cervical agenesis, cervical atresia, and cervical cord or fragment are the four types of cervical aplasia(Figure 2). Dealing with the complete vaginal atresia is challenging, and it remains unclear whether the outcomes of preserving uterus are associated with the cervical status. In this study, we reported our diagnosis and treatment experience in congenital complete vaginal atresia combined with cervical aplasia in the West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University over the past 18 years. Combining with the literature review, we also tried to investigate the feasibility of preserving the uterus for such cases.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic diagram of four kinds of congenital cervical aplasia

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nineteen patients with congenital complete vaginal atresia and cervical aplasia were identified from the West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University database from August 2002 to August 2020. The diagnosis criteria were following: (a) Typical clinical symptoms (abdominal pain or periodic abdominal pain, pelvic mass, primary amenorrhea, etc.); (b) there is no vaginal introitus; (c) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicating complete vaginal atresia and cervical aplasia; (d) if the MRI data were unavailable, the two‐dimensional ultrasound indicating hematoma in the uterus, and there is no vaginal cavity; (e) no vaginal wall found during the operation; (f) the cervical biopsy after hysterectomy confirming the cervical status; (g) the two‐dimensional ultrasound after the operation could help assess diagnosis. Criteria 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were essential, while criteria 6 and 7 were regarded as accompanying factors confirming the diagnosis.

All the included patients underwent operations in our hospital. Patients with Mayer‐Rokitansky‐Kuster‐Hauser syndrome, transverse vaginal septum, and imperforate hymen were excluded. The records of the eligible patients were retrospectively analyzed. The data, such as age, menstruation, signs and symptoms, preoperative MRI results, surgical procedures, the length and width of neovagina after at least 3 months follow up, vaginal stenosis, or recurrent pelvic inflammation, were extracted. The information about sexual activity and the pregnancy outcomes were collected via telephone follow up.

Furthermore, a digital Pub Med search was performed to identify articles published between January 1990 and December 2019 reporting on complete vaginal atresia with cervical aplasia cases. The following search terms were used: “Vaginal atresia,” “vaginal aplasia,” “vaginal agenesis,“ “cervical atresia” “cervical agenesis“ or “cervical aplasia.” There was no restriction on study design. The inclusion criteria were following: (a) Patients diagnosed with congenital complete vaginal atresia accompanied by cervical aplasia who received surgery for the first time and preserved the uteri; (b)the main outcomes were stenosis of vagina or cervix, pelvic inflammation; whether a second surgical treatment was needed, length and width of the new vagina. Preclinical (animal) studies and studies reporting duplicate data from another study were excluded.

The manifestations, treatments, and outcomes were summarized using descriptive statistics. The correlations between the two variables were compared using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 17.0. (IBM, Armonk, New York). A P‐value of<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Symptoms and signs

A total of 19 patients with age ranging from 10 to 22 years (median age of 14 years old) were included. Periodic abdominal pain (36.8%), abdominal pain (63.2%), primary amenorrhea (31.6%), and pelvic mass (100%) were the primary signs and symptoms.

3.2. Co‐existing cervical aplasia

Patients were accompanied by different types of cervical aplasia. Five patients were with complete cervical atresia (26.3%), 11 patients were with cervical external os obstruction (57.9%),and three patients were with cervical agenesis (15.8%).

3.3. Co‐existing other anomalies

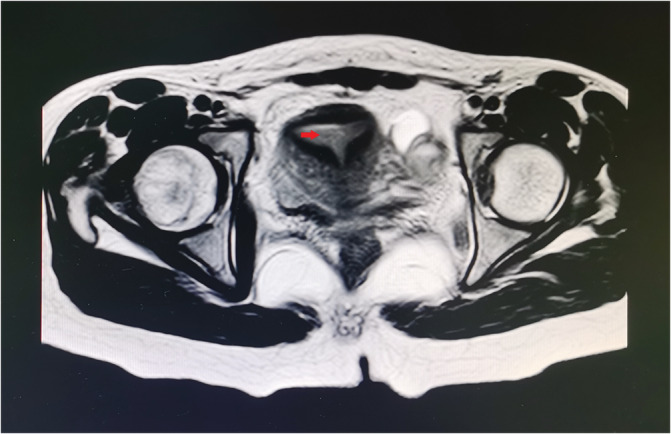

In addition to congenital vaginal atresia and cervical aplasia, two patients had a “T” shape uterus (Figure 3). Other anomalies, such as septum uterus, renal agenesis, urogenital fistula, or vertebral malformation, were not reported.

FIGURE 3.

T2W pelvic transverse image showing a complete vaginal and cervical atresia case with “T” shaped uterine body. The arrow indicates the “T” shaped uterine cavity

3.4. MRI assessment before operation

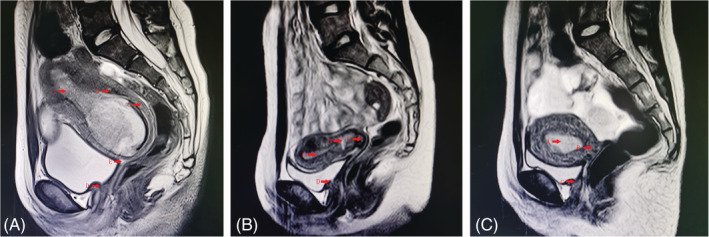

Among the 19 patients, 10 cases received pelvic MRI imaging before the operation. Nine cases received two‐dimensional ultrasound examinations or CT scanning and they were all early cases and some children could not wait so long for the MRI test because of severe abdominal pain. MRI images revealed that all the uterine cavities had expanded, and the atresia sites were above the inner urethral orifice. The MRI could clearly display the uterine body and cervical status (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

T2W pelvic sagittal images showing complete vaginal atresia with different cervical aplasia. A, External cervical os. obstruction. Arrow A indicates an expanded uterine cavity, arrow B indicates a dark cervical interstitial ring, arrow C indicates intermediate brightness cervical muscle, which is continuous with uterine muscular layer, arrow D indicates the level of the inner urethral orifice, and arrow E indicates the obstructed external cervical os. B, Complete cervical atresia. Arrow A indicates an expanded uterine cavity; arrow B indicates atresic cervical canal; arrow C indicates the blinded cervix; arrow D indicates the level of the inner urethral orifice. C, Cervical agenesis. Arrow A indicates an expanded uterine cavity; arrow B indicates a blinded lower segment of the uterus; arrow C indicates the level of the inner urethral orifice

3.5. Treatment and outcomes

Thirteen patients underwent a hysterectomy, six of whom were with cervical external os obstruction, four were with complete cervical atresia, and three were with cervical agenesis. The operations were successful, and none of the patients developed complications after the surgery. Among these cases, two 22‐year‐old patients received vaginoplasty following hysterectomy, and the neovagina was successfully created. Six patients preserved the uteri and underwent tracheloplasty and vaginoplasty through vaginal approach. The clinical features and surgical outcomes are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Outcomes of complete vaginal atresic patients received vaginoplasty

| Case | Cervical aplasia | Stenosis /adhesion | Pelvic inflammation | Second vaginoplasty | Hysterectomy | Neovaginal Length(cm) | Neovaginal Width(cm) | Sexual active | Pregnant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EosO | Yes | No | Yes | No | 9 | 4 | Yes | No |

| 2 | EosO | Yes | No | Yes | No | 5 | 2 | Yes | No |

| 3 | EosO | No | No | No | No | 7 | 3 | No | No |

| 4 | EosO | No | No | No | No | 6 | 3 | No | No |

| 5 | Agenesis | Yes | Yes | No | No | 6 | 2 | No | No |

| 6 | Atresia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesa | — | — | No | No |

Abbreviation: EosO, external os obstruction.

The patient received hysterectomy 2 years after the first vaginoplasty because of recurrent pelvic inflammation.

3.6. Feasibility of preserving the uterus

To investigate the feasibility of preserving the uterus for complete vaginal atresia, we increased the sample by literature searching. One hundred and one cases with complete vaginal atresia, who received cervicovaginal anastomosis or uterovaginal anastomosis, were identified from the literature5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 .The outcomes of these patients are shown in Table 2. Among the 101 cases, 40 cases were accompanied by cervical external os obstruction, nine cases had cervical atresia, one case had a cervical cord, and 13 cases had cervical agenesis. In 38 cases, the types of cervical aplasia were not definitely described in the articles. Regardless of the surgery approaches and cervical aplasia types, the data of cases from both our hospital and the literature indicated that the rate of cervical or vaginal stenosis was 17.8% for complete vaginal atresia in all the 107 cases.

TABLE 2.

Outcomes of 101 patients with complete vaginal atresia preserving uteri identified from the literature

| Study | Case | Cervical aplasia(N) | Stenosis/adhesion | Pelvic inflammation | Second surgery | Hysterectomy | Neovaginal Length (cm) | Neovaginal Width (cm) | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ying2017 7 | 4 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 12 mo |

| Kobayashi2016 8 | 1 | Atresia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 36 mo |

| Xie2017 9 | 28 | 6 mo‐13 y | |||||||

|

EosO(25) Atresia(1) NA(2) |

3 1 0 |

0 0 0 |

0 1 0 |

0 0 0 |

8‐10 NA NA |

Two fingers NA NA |

|||

| Zayed2017 10 | 5 | 12‐36 mo | |||||||

|

EosO(1) Atresia(4) |

0 3 |

0 0 |

0 2 |

0 0 |

NA | NA | |||

| NA | NA | ||||||||

| Zhang2015 11 | 10 | 5 ± 2 mo | |||||||

|

EosO(7) Atresia(3) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | NA | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | NA | ||||

| Jain2011 12 | 1 | Agenesis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 5 y |

| Mishra2016 13 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 6 mo |

| Paul2019 14 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.5 | NA | 8 mo |

| Minami2019 15 | 2 | 6 y | |||||||

|

EosO(1) Agenesis(1) |

1 1 |

0 1 |

0 1 |

0 0 |

NA | NA | |||

| NA | NA | ||||||||

| He2014 16 | 1 | Cord | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 18 mo |

| Jeon2016 17 | 2 | EosO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6–8 | 3 | 6 y |

| Kimble2015 18 | 1 | EosO | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | 6 y |

| Hampton1990 19 | 1 | EosO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 8 y |

| Bugmann 2002 20 | 1 | Agenesis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 3 mo |

| Leng 2002 5 | 3 | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1‐168 mo |

| Fedele2008 21 | 12 | 6 ± 2.4 y | |||||||

|

EosO(2) Agenesis(10) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 ± 1.6 | NA | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 ± 1.6 | NA | ||||

| Jasonni2007 22 | 1 | NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 5 mo |

| Shen2016 23 | 26 | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.5‐8.0 | NA | 2‐46 mo |

Abbreviations: EosO, external os obstruction; NA, not available; Mo, months; y, years.

Extracting the data of 69 cases whose cervical conditions were definite, we performed a subgroup analysis for these cases. The rate of stenosis of vagina/cervix was 15.9% in patients with cervical external os obstruction, while it was 40% in patients with the other types of cervical aplasia, such as cervical atresia, cervical cord, and cervical agenesis (P = .026). The rate of recurrent pelvic inflammation and hysterectomy was 2.3% in patients with cervical external os obstruction and 8% in patients with the other types of cervical aplasia (P = .296).

4. DISCUSSION

In complete vaginal atresia, if cervical aplasia occurs concurrently, the cervical canal needs to be opened so as to solve the issue of menstrual blood accumulation. The comprehensive analysis of data from our hospital and the literature showed that patients with cervical external os obstruction had a statistically lower risk of vaginal/cervical stenosis than patients with cervical atresia, agenesis, and cervical cord (P = .026). Though there was no significant difference, the cervical external os obstruction cases showed a tendency of lower pelvic inflammation and hysterectomy rate. Therefore, for the cervical agenesis, complete cervical atresia, and cervical cord, there is a high risk of cervical stenosis, even when the cervix is opened, thus, hysterectomy should be recommended first. The vaginoplasty is recommended to be performed in late adolescence or young adulthood when the patient is mature enough to agree to the procedure 24. Xie et al 6 proposed another cervical aplasia classification criteria based on anatomy. Based on their experience, they suggested that the cervical canal with blind end could preserve the uterus through vaginal and cervical reconstruction. At the same time, the cases with a short or long solid cervix should receive hysterectomy and vaginoplasty, which is somewhat consistent with our result. Considering most of the included studies were case reports with relatively higher publication bias, it is speculated that uterus preservation may be feasible for patients with cervical external os obstruction.Gynecologists8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 20, 21 tried to preserve uterus and fertility for the patients with complete cervical atresia or cervical fibrous cord, but the sample size was small. More high quality clinical controlled trials with longer follow‐up are needed for further assessment.

By studying the MRI images, we found all the cases had expanded uterine cavity. This may occur because the cervical wall's ductility is lower, and the menstrual blood accumulates in the uterine cavity and then reaches the pelvis through the fallopian tubes. When the cervical isthmus develops well, there might be less blood accumulation in the uterine cavity. The cervical canal expands largely, which could mimic distal vaginal atresia in the MRI image. In such a situation, we found that the obstructed site of complete vaginal atresia was usually above the inner urethral orifice. As MRI allows for a comprehensive evaluation of female genital tract anomalies,25it should be used to assess the atresic site of the vagina and the co‐existing cervical abnormalities before the operation.

Successful vaginoplasty should result in the neovagina having a new vaginal vault with sufficient size, adequate introitus, and an acceptable cosmetic external appearance.26 For the complete vaginal atresia with a longer atresic segment, utilization of graft is necessary. Various methods have been proposed for vaginoplasty, such as constructing neovagina out of bowel segments, pudenda‐thigh flaps, fasciocutaneous flaps, gracilis myocutaneous flaps, labia minora flaps, peritoneum and bladder mucosa, amnion, autologous buccal mucosa, and the tissue‐engineered biomaterial. Different methods may have different complications, such as unpleasant odor and malodorous mucous discharge for rectosigmoid vaginoplasty, postoperative pain at the donor site, and keloid formation for a skin graft. In our hospital, biomaterial graft (SIS, Cook Biotech Inc.) is commonly used without severe complications, such as bladder injury, rectal injury, or hematoma. During the follow‐up, the perineal appearance was normal.

In conclusion, for complete vaginal atresia cases, total hysterectomy could avoid the risk of cervical or vaginal stenosis, adhesion and pelvic inflammation due to the poor drainage of menstrual blood, so it is still preferred by many gynecologists. As for patients with cervical external os obstruction, the cervicovaginal anastomosis may offer an alternative treatment for preserving menstruation or even fertility. However, the experience from reconstructive cervicovaginal anastomosis is limited, and there are still many things that need to be investigated, such as evaluation of successful surgery results, sustaining the cervical canal, or preventing stenosis of the vagina and cervix.

DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Though the patient's radiological images are utilized in the manuscript, the personal information is concealed and permission has been obtained from the patient's parents for presentation.

Mei L, Zhang H, Chen Y, Niu X. Clinical features of congenital complete vaginal atresia combined with cervical aplasia: A retrospective study of 19 patients and literature review. Congenit Anom. 2021;61:127–132. 10.1111/cga.12417

REFERENCES

- 1.American Fertility Society . The AFS classification of adnexal adhesion, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grigoris FG, Stephan G, Attilio DSS, et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(8):2032‐2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acién P, Acién MI. The history of female genital tract malformation classifications and proposal of an updated system. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(5):693‐705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruggeri G, Gargano T, Antonellini C, et al. Vaginal malformations: a proposed classification based on embryological, anatomical and clinical criteria and their surgical management (an analysis of 167 cases). Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28(8):797‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leng J, Lang J, Lian L, et al. Congenital vaginal atresia: report of 16 cases. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2002;37(4):217‐219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Z, Zhang X, Liu J, et al. Clinical characteristics of congenital cervical atresia based on anatomy and ultrasound: a retrospective study of 32 cases. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:10‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Chen YS, Hua KQ. Outcomes in patients undergoing robotic reconstructive uterovaginal anastomosis of congenital cervical and vaginal atresia. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13(3):1‐6. 10.1002/rcs.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi A, Fukui A, Funamizu A. et al. Laparoscopically Assisted Cervical Canalization and Neovaginoplasty in a Woman with Cervical Atresia and Vaginal Aplasia. 2017;6(1):31‐33. 10.1016/j.gmit.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Z, Zhang X, Zhang N, et al. Clinical features and surgical procedures of congenital vaginal atresia—a retrospective study of 67 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;217:167‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zayed M, Fouad R, Elsetohy KA, Hashem AT, AbdAllah AA, Fathi AI. Uterovaginal anastomosis for cases of cryptomenorrhea due to cervical atresia with vaginal aplasia: benefits and risks. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(6):641‐645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Han T, Ding J, Hua K. Combined laparoscopic and vaginal cervicovaginal reconstruction using split thickness skin graft in patients with congenital atresia of cervix. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(6):10081‐10085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutan J, Reema S. Laparoscopic management of congenital cervico‐vaginal agenesis. J Gynecol Endosc Surg. 2011;2(2):94‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra V, Saini SR, Nanda S, Choudhary S, Roy P, Singh T. Uterine conserving surgery in a case of cervicovaginal agenesis with unicornuate uterus. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2016;9(4):267‐270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul PG, Akila B, Aastha A, Paul G, Saherwala T. Laparoscopy assisted neocervicovaginal reconstruction in a rare case of Müllerian anomaly:cervicovaginal aplasia with unicornuate uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(6):1261‐1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minami C, Tsunematsu R, Hiasa K, Egashira K, Kato K. Successful surgical treatment for congenital vaginal agenesis accompanied by functional uterus: a report of two cases. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019;8:76‐79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He H, Guo H, Han J, Wu Y, Zhu F. An atresia cervix removal, lower uterine segment substitute for cervix and uterovaginal anastomosis: a case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(1):93‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon GH, Kim SH, Chae HD, Kim CH, Kang BM. Simple uterovaginal anastomosis for cervicovaginal atresia diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging: a report of two cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42(6):738‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimble R, Molloy G, Sutton B. Partial cervical agenesis and complete vaginal atresia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(3):e43‐e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampton HL, Meeks GR, Bates GW, Wiser WL. Pregnancy after successful vaginoplasty and cervical stenting for partial atresia of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76(5, pt 2):900‐901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugmann P, Amaudruz M, Hanquinet S, La Scala G, Birraux J, Le Coultre C. Uterocervicoplasty with a bladder mucosa layer for the treatment of complete cervical agenesis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(4):831‐835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedele L, Bianchi S, Frontino G, Berlanda N, Montefusco S, Borruto F. Laparoscopically assisted uterovestibular anastomosis in patients with uterine cervix atresia and vaginal aplasia. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(1):212‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasonni VM, La Marca A, Matonti G. Utero‐vaginal anastomosis in the treatment of cervical atresia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(12):1517‐1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen F, Zhang XY, Yin CY, Ding JX, Hua KQ. Comparison of small intestinal submucosa graft with split‐thickness skin graft for cervicovaginal reconstruction of congenital vaginal and cervical aplasia. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(11):2499‐2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee on Adolescent Health Care . ACOG Committee Opinion No. 728: Müllerian Agenesis: Diagnosis, Management, And Treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):e35‐e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maciel C, Bharwani N, Kubik‐Huch RA, et al. MRI of female genital tract congenital anomalies: European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(8):4272‐4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin C, Luo G, Du M, et al. The clinical application of laparoscope‐assisted peritoneal vaginoplasty for the treatment of congenital absence of vagina. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(3):320‐324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]