Abstract

Background

Individuals with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may have persistent symptoms following their acute illness. The prevalence and predictors of these symptoms, termed postacute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; PASC), have not been fully described.

Methods

Participants discharged from an outpatient telemedicine program for COVID-19 were emailed a survey (1–6 months after discharge) about ongoing symptoms, acute illness severity, and quality of life. Standardized telemedicine notes from acute illness were used for covariates (comorbidities and provider-assessed symptom severity). Bivariate and multivariable analyses were performed to assess predictors of persistent symptoms.

Results

Two hundred ninety patients completed the survey, of whom 115 (39.7%) reported persistent symptoms including fatigue (n = 59, 20.3%), dyspnea on exertion (n = 41, 14.1%), and mental fog (n = 39, 13.5%), among others. The proportion of persistent symptoms did not differ based on duration since illness (<90 days: n = 32, 37.2%; vs >90 days: n = 80, 40.4%; P = .61). Predictors of persistent symptoms included provider-assessed moderate–severe illness (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.24; 95% CI, 1.75–6.02), female sex (aOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 0.98–4.04; >90 days out: aOR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.01–4.95), and middle age (aOR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.07–4.03). Common symptoms associated with reports of worse physical health included weakness, fatigue, myalgias, and mental fog.

Conclusions

Symptoms following acute COVID-19 are common and may be predicted by factors during the acute phase of illness. Fatigue and neuropsychiatric symptoms figured prominently. Select symptoms seem to be particularly associated with perceptions of physical health following COVID-19 and warrant specific attention on future studies of PASC.

Keywords: COVID-19, PASC, prolonged, SARS-CoV-2, symptoms

In response to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, health systems in the United States rapidly reorganized in March 2020 to create home monitoring programs [1]. The resulting systems did not anticipate prolonged symptoms following acute coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) until reports arose in personal accounts and on social media [2]. Subsequent evidence emerged that persistent symptoms are common for both hospitalized [3] and nonhospitalized [4, 5] cohorts, and these patients have described challenges with stigma as well as difficulty accessing care for their symptoms [6]. Later reports indicate that disruption to usual activities and impaired quality of life may last months [7–9]. Postacute viral syndromes have been described for other viral illnesses including Ebola [10], Chikungunya [11], and dengue [12]. Of particular concern, survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) hospitalized from 2001 to 2003 showed persistent pulmonary dysfunction [13] as well as chronic fatigue and psychiatric illnesses [14] lasting years. In this context, there is a clear need to characterize the long-term outcomes of COVID-19. In addition to understanding predictors of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), understanding the long-term impact on individuals’ health and well-being will inform future standards of care for treating patients with COVID-19.

Descriptions of the clinical syndrome of PASC have defined symptoms between 4 and 12 weeks as “ongoing symptomatic COVID-19” and >12 weeks as “post-COVID-19 syndrome” [15]. The underlying pathophysiology is not clear, with studies highlighting possible roles of elevated inflammatory markers, lung dysfunction, muscle weakness, and hypometabolism seen on brain positron emission tomography [16–20]. One report using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging could not link specific symptoms to specific organ impairment [21]. A meta-analysis of 47 910 patients found that the most frequent symptoms include fatigue, headache, attention disorder, hair loss, and dyspnea [22] and noted a high degree of heterogeneity in published studies, with a need for future studies to stratify results by patient baseline characteristics and disease severity. Individual cohort studies have reported a variety of specific risk factors for prolonged symptoms including female sex [23–25], higher body mass index (BMI) [23, 24], middle age [26], older age [24, 27], and underlying autoimmunity [9], while 1 study found no significant predictors [28]. Features of acute COVID-19 may predict PASC, with cohort studies finding increasing risk for patients with >5 acute symptoms [24], specific acute symptoms (chest pain, fatigue, fever, olfactory impairment, headaches, or diarrhea) [25], severe acute symptoms [29], and hospitalization [26].

We previously described durations of symptoms in acute COVID-19 in a telemedicine cohort and found that they were significantly associated with the severity of symptoms at initial medical evaluation (5–6 days after onset) [30]. We also noted a higher rate of asthma among patients requiring ongoing telemedicine care for symptoms beyond 6 weeks (42%) compared with the whole cohort (13%) [31]. We hypothesize that initial symptom severity as well as select comorbidities such as asthma will also predict prolonged symptoms (>90 days). Lastly, using modified quality of life questions, we explored which persistent symptoms were associated with lower ratings of physical and emotional health.

METHODS

Study Population

Our study population consisted of patients enrolled in Emory Healthcare’s Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic (VOMC) in Atlanta, Georgia, between March 24 and September 20, 2020.

Patients were offered enrollment in VOMC during results notification calls following a positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test at an Emory site (2 large throughput outpatient testing centers and the emergency departments of 4 acute care hospitals). Patients in VOMC underwent standardized telemedicine assessment (synchronous audio/video visit within 48 hours of RT-PCR result, typically on illness day 5–6) by Emory Healthcare providers as previously described [32]. Most intake visits were performed by physicians (general internal medicine), and the standard duration was 40 minutes to allow for both an assessment of risk for severe COVID-19 and symptom management advice. A dedicated telephone team (advanced practice providers and registered nurses) called patients at regular intervals (every 12–48 hours based on acuity) for up to 21 days depending on symptom severity and risk factors for hospitalization. Patients needing re-assessment could be seen by telemedicine (VOMC physicians or their primary care provider) or in person at an acute respiratory clinic. Patients were discharged from VOMC after completing home quarantine if their symptoms were improving in severity, or upon hospital admission (if admitted).

Our inclusion criteria were (a) adults at least 18 years of age, (b) previous positive test for SARS-CoV-2 (RT-PCR or rapid antigen test), (c) with a valid email address in the Emory electronic health record, and (d) discharge from the Emory VOMC. The majority of VOMC patients during the study period were tested by RT-PCR at Emory, but patients with a positive test at an outside site (rapid test or RT-PCR) were eligible if referred to VOMC by an Emory provider. Email was a standard method for patient communication during the study period (sending telemedicine visit login instructions, for example).

Data Collection

A quantitative, cross-sectional survey was created using Qualtrics Online Survey Software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) to collect participant-reported information on persistent COVID-19 symptoms and recall of acute symptoms. From August to November of 2020, an email was sent to eligible participants inviting them to complete the survey using an identified link. Nonrespondent patients were sent 4 reminder emails at 2-week intervals and called once by study staff in the final week before the survey was closed. The survey included research consent, general information (race, sex, education, income level), aspects of the participant’s experience with SARS-CoV-2 infection such as severity of their acute disease, which symptoms were ongoing at the time of the survey (33 individual symptoms), physical and emotional quality of life, and access to health care. Specific symptoms of interest are listed in the tables. Data on specific comorbidities and provider-assessed severity of acute illness at VOMC intake visit were extracted from the medical record for each participant. Provider-assessed severity was defined as “mild”: cough without shortness of breath or wheeze and/or fever, chills, and other mild systemic symptoms; “moderate”: any mild symptoms plus dyspnea on exertion, wheezing and/or midchest tightness; “severe”: shortness of breath at rest, pulse oximetry <92%, pleuritic pain and concerning systemic symptoms like syncope, severe weakness, confusion or acute decline in functional status [30, 32]. The survey was closed after 3 months of gathering responses.

Data Analysis

Data from the survey were exported from Qualtrics into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Summary statistics were reported using frequencies and means/medians where appropriate. Bivariate analyses using the chi-square test, t test, or crude logistic regression (single variable) were performed between the main outcome (persistent symptoms), the main exposure (provider-assessed severity of acute illness), and all covariates. For the main logistic regression, we analyzed the occurrence of “any” persistent symptom of all the symptoms queried. For those who reported persistent symptoms at the time of the survey, we divided these respondents into early chronic (<90 days) and prolonged chronic symptoms (>90 days). This cutoff was chosen due the literature, including more recent NICE guidelines, using >12 weeks as falling into PASC [15, 33]. Covariates included age, sex, race, comorbid conditions, hospitalization, and income. Age was divided into 3 categories for the regression: young (18–39 years), middle-aged (40–59 years), and older (60 years and older). These groupings contained similar numbers of years across groups and represented clinically meaningful age groups: young, middle-aged, and older adults. Multivariate logistic regression was then performed using any persistent symptom as an outcome, with provider-assessed severity (mild vs moderate or severe) as the main exposure and age (grouped in categories), sex, hospitalization, and all comorbidities as confounders in the initial model. Tests of collinearity and interactions were performed, and variables were dropped if necessary. Backward stepwise elimination was then undertaken to determine the final model. A second model was conducted limited to participants who answered the survey at ≥90 days.

To determine if certain categories of symptoms had unique associations with potential risk factors for persistence of these symptoms, we divided them into respiratory (dry or wet cough, dyspnea on exertion, shortness of breath at rest, chest tightness or pain), systemic (fatigue, chills, weakness, joint pains, muscle pains, dizziness), neuropsychiatric (headache, mental fog, difficulty sleeping, irritability, feeling depressed, feeling anxious), and loss of taste and/or smell. We then performed bivariate analyses with these outcomes and all main predictors as per the initial analyses above. Also compared with these categories of symptoms were individual ratings of severity of acute symptoms related to that specific persistent symptom (like lower respiratory symptoms for persistent respiratory symptoms).

Multivariate logistic regression was performed for each category of symptom using the main exposure of provider-rated illness severity and other covariates as listed above. Model diagnostics were also undertaken including testing of collinearity, interactions, and confounding. Individual ratings of symptom severity were not included in the multivariate model.

Lastly, all symptoms were compared with measures of physical and emotional health to determine associations with persistent symptoms and 3 different self-reported markers of quality of physical and emotional health—whether they report their physical health as worse or much worse than before their COVID-19 (vs same or better), whether their physical health limits their daily activities, and whether their emotional health limits their daily activities (yes or no). Bivariate chi-square analyses were performed with each symptom except for those persistent symptoms that were reported in <5 individuals.

Ethical Approvals

The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided electronic consent at the outset of the emailed survey.

RESULTS

Basic Descriptive Factors

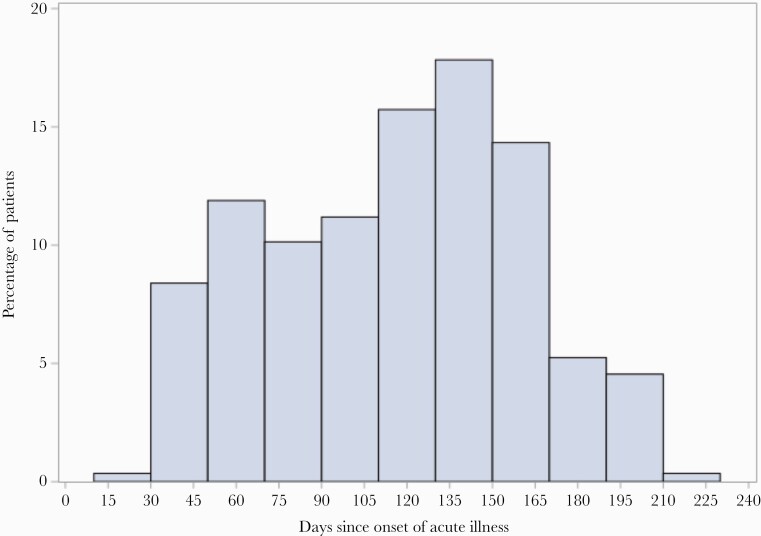

The survey was emailed to 1111 eligible patients. Two hundred ninety individuals (26.1%) consented and completed the questionnaire, of whom 216 (75%) were women and 194 (67.4%) reported a comorbid condition (Table 1). All respondents except 1 had documented positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2; a single patient had documented positive rapid antigen test. The median age (range) was 44 (18–84) years, and 125 (43.1%) were Black. The median length of time after diagnosis of their acute COVID-19 (range) was 119 (26–220) days, with 70% responding at >90 days after their acute illness (Figure 1). Of the sample, 35 (12.6%) were hospitalized, and at the initial intake VOMC visit, 182 (68.7%) were determined to have mild or resolved symptoms, 81 (30.1%) moderate, and 2 (0.8%) severe. The most common comorbid condition was obesity (BMI >30 kg/ m2), followed by hypertension and asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Table 1). Half of the study sample experienced self-reported weight loss during their illness, with a mean loss (SD) of 10.7 (7.4) lbs (Supplementary Table 1). About 25% of individuals said their thinking was worse or much worse than before their acute COVID-19 illness, and 25.6% said their physical health was somewhat or much worse than before their acute illness (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic Demographics and Baseline Factors for Persistent Symptoms vs No Persistent Symptoms at Time of Survey (Ranging 1–7 Months Post–Acute Illness); Table 2 Has These Broken Down by Early (<90 Days) and Late (>90 Days)

| Persistent Symptoms | No Persistent Symptoms | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 115 | n = 175 | n = 290 | |

| Age, median (range), y | 46 (20–84) | 40 (18–83) | 44 (18–84) |

| Sex,a No. (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (19.3) | 50 (28.7) | 72 (25) |

| Female | 92 (80.7) | 124 (71.3) | 216 (75) |

| Race/ethnicity,b No. (%) | |||

| White | 50 (44.6) | 70 (41.4) | 120 (42.7) |

| Black | 46 (41.1) | 79 (46.8) | 125 (44.5) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 9 (5.3) | 4 (3.6) | 13 (4.6) |

| Asian | 6 (5.4) | 6 (3.6) | 12 (4.3) |

| Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 4 (2.4) | 6 (5.4) | 10 (3.6) |

| Provider rated moderate—severe dx,c No. (%) | 51 (48.1) | 32 (20.1) | 83 (31.3) |

| Hospitalized,d No. (%) | 20 (18.4) | 15 (8.9) | 35 (12.6) |

| Any comorbidity,e No. (%) | 76 (67.3) | 118 (67.4) | 194 (67.4) |

| Lung diseasef | 24 (23.5) | 25 (16) | 49 (19) |

| Obesity | 54 (47.8) | 81 (46.3) | 113 (39.2) |

| Hypertension | 27 (26.5) | 47 (30.1) | 74 (28.7) |

| Heart diseaseg | 7 (6.9) | 9 (5.8) | 16 (6.2) |

| Cancer | 6 (5.9) | 15 (9.6) | 21 (8.1) |

| Diabetes | 11 (10.8) | 14 (9.0) | 25 (9.7) |

| Immune suppressionh | 12 (11.8) | 19 (12.2) | 31 (12) |

| Kidney disease | 5 (4.9) | 3 (1.9) | 8 (3.1) |

| Incomei | |||

| <$30 000 | 8 (7.5) | 24 (15.4) | 32 (12.2) |

| $30 000–$60 000 | 32 (29.9) | 54 (36.6) | 86 (32.7) |

| $60 000–$100 000 | 31 (29.0) | 34 (21.8) | 65 (24.7) |

| >$100 000 (ref) | 36 (33.6) | 44 (28.2) | 80 (30.4) |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

aAvailable for 288 participants.

bAvailable for 281 participants.

cAvailable for 265 participants.

dAvailable for 278 participants.

eComorbidities available for 258 participants, except for obesity, which is available for 288.

fDefined as asthma, COPD, or other chronic lung disease.

gDefined as coronary artery disease or heart failure.

hDefined as biologic or other immunosuppressive medications including chronic corticosteroid at ≥20 mg prednisone daily, detectable HIV VL, or CD4 count <200 cells/mm3) or other specified immunodeficiency.

iAvailable for 263 participants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the time from onset of COVID-19 to completion of survey by study participants.

Symptoms

Overall, 115 (39.7%) had persistent symptoms at the time of the survey (Supplementary Table 2), with the majority of these individuals (n = 67, 58.8%) reporting 4 or more symptoms. Only 16 (14%) reported 1 symptom, 20 (17.5) reported 2 symptoms, 11 (9.7%) reported 3 symptoms, and 1 individual did not report which symptom(s) they had. The most common persistent symptom was fatigue (n = 59, 20.3%), followed by dyspnea on exertion (n = 41, 14.1%) and mental fog (n = 39, 13.5%) (Supplementary Table 2). Table 2 shows the study sample split into 2 time periods: 26–90 days after the acute COVID-19 phase (“early,” about 1–3 months) and 90–220 days after the acute COVID-19 phase (“late,” >3 months). There were similar proportions of patients with continued symptoms in the early group (n = 34, 38.6%) and the late group (n = 79, 39.9%; P = .84). Twenty-nine symptoms are tabulated in Table 2, and all of them were very similarly ranked in frequency whether the participant was in the early or late group. Loss of smell was common at 11.9% (n = 33) even in the late group (n = 21, 10.6%), twice as frequent as loss of taste (n = 18, 6.3%). To account for the wide range of days post-COVID-19 that participants answered the survey, t test analyses were performed for all symptoms based on days postillness; these tests did not show statistically significant differences based on when participants took the survey.

Table 2.

Descriptive Variables Stratified by Time Since Acute COVID-19 Illness; P Value Shown Based on Chi-square or T Test Where Appropriate; Significant Values <.05; Table Based on 286 Participants as 4 Were Missing Dates of Acute Illness

| . | 26–89 (Median, 61) Days Post–Acute COVID-19 | 90–220 (Median, 139) Days Post–Acute COVID-19 | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 88 | n = 198 | n = 286 | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46 (16) | 45 (14) | 45 (15) | .35 |

| Female sex | 67 (76.1) | 147 (74.2) | 214 (74.8) | .73 |

| Racea (279) | .26 | |||

| White | 41 (47.7) | 79 (40.9) | 120 (43) | |

| Black/African American | 33 (38.4) | 90 (46.6) | 123 (44.1) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (3.5) | 10 (5.2) | 13 (4.7) | |

| Asian | 3 (3.5) | 9 (4.7) | 12 (4.3) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Other | 6 (7) | 4 (2.1) | 10 (3.6) | |

| Hospitalized | 9 (10.6) | 25 (13.3) | 34 (12.4) | .54 |

| Provider-defined disease severityb | .78 | |||

| Mild | 56 (67.5) | 126 (69.2) | 182 (68.7) | |

| Moderate | 27 (32.5) | 54 (29.7) | 81 (30.6) | |

| Severe | 0 | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Persistent symptoms | ||||

| Any | 34 (38.6) | 79 (39.9) | 113 (39.5) | .84 |

| Fatigue | 17 (19.3) | 42 (21.2) | 59 (20.6) | .71 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 16 (18.2) | 25 (12.6) | 41 (14.3) | .22 |

| Mental fog | 12 (13.6) | 27 (13.6) | 39 (13.6) | 1.0 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 10 (11.4) | 22 (11.1) | 32 (11.2) | .95 |

| Loss of smell | 12 (13.6) | 21 (10.6) | 33 (11.5) | .46 |

| Headache | 8 (9.1) | 23 (11.6) | 31 (10.8) | .53 |

| Dry cough | 8 (9.1) | 17 (8.6) | 25 (8.7) | .89 |

| Feeling depressed | 7 (8.0) | 19 (9.6) | 26 (9.1) | .66 |

| Muscle aches | 7 (8.0) | 17 (8.6) | 24 (8.4) | .86 |

| Joint pains | 6 (6.8) | 16 (8.1) | 22 (7.7) | .71 |

| Weakness | 9 (10.2) | 12 (6.1) | 21 (7.3) | .21 |

| Heart palpitations | 5 (5.7) | 16 (8.1) | 21 (7.3) | .47 |

| Anxiety/ nervousness | 4 (4.6) | 15 (7.6) | 19 (6.6) | .34 |

| Chest tightness/pain | 6 (6.8) | 13 (6.6) | 19 (6.6) | .94 |

| Loss/change in taste | 7 (8.0) | 11 (5.6) | 18 (6.3) | .44 |

| Sinus congestion | 4 (4.6) | 13 (6.6) | 17 (5.9) | .51 |

| Irritability | 5 (5.7) | 11 (5.7) | 16 (5.7) | .97 |

| Back pain | 4 (4.6) | 11 (5.6) | 15 (5.2) | .72 |

| Dizziness | 3 (3.5) | 8 (4.0) | 12 (4.2) | .84 |

| Rhinorrhea | 2 (2.3) | 9 (4.6) | 11 (3.9) | .36 |

| Ear fullness | 2 (2.3) | 8 (4.0) | 10 (3.5) | .45 |

| Heartburn | 2 (2.3) | 8 (4.0) | 10 (3.5) | .45 |

| Shortness of breath at rest | 2 (2.3) | 7 (3.5) | 9 (3.2) | .57 |

| Nausea | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (1.8) | .60 |

| Rash | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (1.4) | .80 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 (0) | 4 (2.0) | 4 (1.4) | .18 |

| Chills | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.1) | .92 |

| Sore throat | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.7) | .55 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | .34 |

| Loss of appetite | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | — |

| Other symptoms | 3 (3.4) | 11 (5.6) | 14 (4.9) | .44 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

aAvailable for 279 participants.

bAvailable for 265 participants.

Predictors of Persistent Symptoms

Since the 2 time periods (early and late) did not differ in the frequency of persistent symptoms or frequency of specific symptoms, we analyzed the study sample first in aggregate. In addition, we repeated the logistic regression model with only those “late” participants who answered the survey at ≥90 days from acute illness. Our main predicted exposure of moderate to severe disease severity at the time of diagnosis (intake visit) was highly associated with persistent symptoms on both unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 3), with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 3.24 (95% CI, 1.75–6.02). This was similar in the ≥90 days group. Being hospitalized was also more common in those with persistent symptoms but did not reach statistical significance on the adjusted logistic regression models. In the overall group, female sex was not statistically significantly associated with persistent symptoms, but when the model was limited to the late reporters, female sex (aOR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.10–6.79) was associated. Middle age (aOR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.07–4.03) was associated with having persistent symptoms in both adjusted models. The only comorbid condition to have a significant result in the model was hypertension, which had a negative association with persistent symptoms (aOR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.22–0.94) that remained when limited to the longer duration of symptoms (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate Analyses and Multivariate Logistic Regression Showing Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratio, Respectively, for the Outcome of Persistent Symptoms, With Moderate–Severe Acute Illness as the Main Exposure; Bolded Values Are Significant With a P Value of <.05

| Variable | Persistent Symptoms OR |

95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | aOR Limited to >90 Days | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider-rated moderate–severe dx (265) | 3.68 | 2.14–6.34 | 3.24 | 1.75–6.02 | 3.00 | 1.40–6.41 |

| Hospitalized (278) | 2.31 | 1.12–4.73 | 2.22 | 0.82–6.07 | 2.15 | 0.66–7.02 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–39 | 1 (ref) | 1 | ||||

| 40–59 | 1.89 | 1.11–3.21 | 2.08 | 1.07–4.03 | 2.24 | 1.01–4.95 |

| ≥60 | 1.36 | 0.70–2.65 | 1.80 | 0.77–4.20 | 1.85 | 0.60–5.74 |

| Sex (288) | ||||||

| Male | 1 (ref) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.69 | 0.95–2.98 | 1.99 | 0.98–4.04 | 2.73 | 1.10–6.79 |

| Race/ethnicity | — | — | ||||

| White | 1 (ref) | |||||

| Black | 0.82 | 0.49–1.36 | ||||

| Latinx | 0.62 | 0.18–2.13 | ||||

| Asian | 1.40 | 0.43–4.59 | ||||

| Other | 1.68 | 0.49–5.81 | ||||

| Comorbidity (ref: no comorbidity) |

||||||

| Any | 0.99 | 0.60–1.64 | — | |||

| Obesity | 1.06 | 0.66–1.71 | — | |||

| Hypertension | 0.84 | 0.48–1.46 | 0.45 | 0.22–0.94 | 0.33 | 0.13–0.82 |

| Lung disease | 1.61 | 0.86–3.02 | 1.26 | 0.62–2.55 | 1.30 | 0.55–3.08 |

| Heart disease | 1.20 | 0.43–3.34 | 1.29 | 0.39–4.65 | 0.97 | 0.12–7.59 |

| Diabetes | 1.23 | 0.53–2.82 | — | |||

| Cancer | 0.59 | 0.22–1.57 | — | |||

| Immune suppression | 0.96 | 0.45–2.08 | — | |||

| Renal disease | 2.63 | 0.61–11.25 | — | |||

| Annual income | ||||||

| <$30 000 | 0.41 | 0.16–1.02 | — | |||

| $30 000–$60 000 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.35 | — | |||

| $60 000–$100 000 | 1.11 | 0.58–2.15 | ||||

| >$100 000 (ref) | 1 | — |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; OR, odds ratio.

When persistent symptoms were divided into categories of symptoms (respiratory, neuropsychiatric, systemic, and loss of taste/smell), the provider-assessed severity at VOMC intake visit remained associated with these persistent symptoms (Supplementary Table 3) in unadjusted bivariate analyses. Also included were individual patient ratings of severity of acute symptoms (recall at time of survey) related to that specific persistent symptom (eg, patient-rated severity of acute lower respiratory symptoms for persistent respiratory symptoms). Severe ratings for these were also consistently associated with the persistent chronic system-based symptoms. Interestingly, comorbid lung disease was associated with persistent systemic symptoms (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.13–4.22) and taste/smell symptoms on bivariate analyses (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.01–4.94), but not with persistent respiratory symptoms (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.41–1.90). These did not hold in the final logistic models, however. For those who reported moderate to severe taste and smell disturbance during their acute illness (n = 190, 65.5%), 81% had resolution of their symptoms at the time of their completion of this survey (Supplementary Table 3).

Symptoms Associated With Physical and Mental Health

Table 4 shows associations with individual symptoms and 3 different markers of quality of physical and emotional health. For physical health being worse than before acute COVID-19, the commonly reported persistent symptoms most associated were fatigue (OR, 10.48; 95% CI, 5.47–20.07), muscle aches (OR, 10.47; 95% CI, 3.95–27.81), weakness (OR, 10.76; 95% CI, 3.75–30.84), feeling depressed (OR, 10.35; 95% CI, 4.14–25.9), and mental fog (OR, 9.82; 95% CI, 4.63–20.85). Although less commonly reported and with wide confidence intervals, joint pains (OR, 17.1; 95% CI, 5.56–52.59) and shortness of breath at rest (OR, 11.19; 95% CI, 2.27–55.18) had even stronger associations. For physical health–limiting daily activities, the common symptoms most associated were dyspnea on exertion (OR, 13.68; 95% CI, 5.98–31.28), mental fog (OR, 12.41; 95% CI, 5.41–28.48), headache (OR, 12.24; 95% CI, 4.81–31.17), and joint pains (OR, 12.06; 95% CI, 3.95–36.85). While not a commonly reported symptom, heart palpitations (OR, 16.17; 95% CI, 4.62–56.53) was strongly associated with limitation of daily activities. For emotional health–limiting daily activities, the following symptoms were most associated: irritability (OR, 6.02; 95% CI, 2.02–17.9), feeling depressed (OR, 5.53; 95% CI, 2.35–12.99), back pain (OR, 5.40; 95% CI, 1.78–16.32), feeling anxious (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.78–12.43), and ear fullness (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 1.06–14.04).

Table 4.

Associations, Measured by Odds Ratios, and 95% CIs, Between Individual Persistent Symptoms and Physical and Emotional Health Indicators; Limited to Symptoms That Were Reported by at Least 5 Participants

| Persistent Symptoms | Physical Health Worse Than Before Acute COVID-19 | Physical Health Affects Daily Activities | Emotional Health Affects Daily Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Fatigue | 10.48 (5.47–20.07) | 10.35 (5.36–19.98) | 2.56 (1.41–4.64) |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 8.34 (4.06–17.15) | 13.68 (5.98–31.28) | 2.16 (1.09–4.25) |

| Mental fog | 9.83 (4.63–20.85) | 12.41 (5.41–28.48) | 3.06 (1.53–6.10) |

| Difficulty sleeping | 7.42 (3.36–16.35) | 7.17 (3.16–16.27) | 3.21 (1.52–6.79) |

| Loss of smell | 4.32 (2.05–9.12) | 4.69 (2.19–10.05) | 1.46 (0.68–3.12) |

| Headache | 3.99 (1.84–8.66) | 12.24 (4.81–31.17) | 3.46 (1.62–7.40) |

| Dry cough | 2.34 (1.02–5.36) | 2.01 (0.89–4.54) | 1.09 (0.45–2.62) |

| Feeling depressed | 10.35 (4.14–25.9) | 7.26 (2.93–18.02) | 5.53 (2.35–12.99) |

| Muscle aches | 10.47 (3.95–27.81) | 6.32 (2.52–15.87) | 2.68 (1.15–6.23) |

| Joint pains | 17.1 (5.56–52.59) | 12.06 (3.95–36.85) | 1.77 (0.73–4.31) |

| Weakness | 10.76 (3.75–30.84) | 11.24 (3.66–34.51) | 1.55 (0.62–3.89) |

| Heart palpitations | 4.46 (1.79–11.08) | 16.17 (4.62–56.53) | 2.38 (0.97–5.84) |

| Anxiety/ nervousness | 3.60 (1.40–9.25) | 7.07 (2.46–20.32) | 4.71 (1.78. 12.43) |

| Chest tightness/pain | 7.48 (2.73–20.51) | 5.38 (1.97–14.65) | 1.85 (0.72–4.79) |

| Loss/change in taste | 4.67 (1.71–12.78) | 2.95 (1.12–7.76) | 1.60 (0.60–4.28) |

| Sinus congestion | 2.79 (1.03–7.53) | 5.91 (2.01–17.32) | 1.77 (0.65–4.82) |

| Irritability | 3.15 (1.14–8.74) | 7.42 (2.32–23.72) | 6.02 (2.02–17.9) |

| Back pain | 4.85 (1.66–14.15) | 9.95 (2.73–36.22) | 5.40 (1.78–16.32) |

| Dizziness | 6.43 (1.88–22.05) | 7.19 (1.90–27.22) | 3.63 (1.12–11.78) |

| Rhinorrhea | 3.73 (1.10–12.60) | 6.31 (1.63–24.37) | 2.09 (0.62–7.06) |

| Ear fullness | 4.68 (1.28–17.08) | 9.51 (1.98–45.76) | 3.86 (1.06–14.04) |

| Heartburn | 3.06 (0.86–10.89) | 5.45 (1.38–21.61) | 2.53 (0.71–8.97) |

| Shortness of breath at rest | 11.19 (2.27–55.18) | 4.62 (1.13–18.91) | 1.23 (0.30–5.02) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

We find that chronic symptoms are common in a follow-up survey of patients previously enrolled in a COVID-19 outpatient telemedicine monitoring program, with 40% of patients reporting persistence of at least 1 symptom. We hypothesized based on prior work [30] that initial symptom severity (at the time of telemedicine intake visit) would predict the likelihood of long-term symptoms, and we found this association to be significant. Patient recall of symptom severity (reported at time of survey) had a similar relation, strengthening the internal validity of this finding. We did not find an association between other factors such as demographics or comorbidities and the presence of symptoms at the time of follow-up survey, except for female sex (increased likelihood) and hypertension (decreased likelihood), nor did we find a significant difference between patients responding to the survey closer to their acute illness vs those farther out from their acute illness.

The mechanism(s) underlying the persistence of symptoms beyond acute COVID-19 remains unclear; the finding of a relationship between the severity of acute symptoms (recorded at the end of the first week of illness) and the prevalence of symptoms months later suggests a possible role for acute inflammation and/or viral burden. Subsequent hospitalization may predict risk in the unadjusted comparison but is not significant in the adjusted model. This may be due to the low number of hospitalizations in our cohort, but also to risk factors for hospitalization (age, male sex, comorbidities) not being directly associated with risk of long-term symptoms.

These findings are significant in public health messaging and individual risk communication. In addition to baseline patient characteristics that may predict PASC, there are likely disease characteristics (such as severity of acute symptoms), meaning the risk of PASC may not be clear until one has acute COVID-19. Therefore, adults naïve to SARS-CoV-2 cannot be reassured that their risk of PASC is low before having the infection. Furthermore, we did not find a difference in the frequency of persistent symptoms in our “early” (day 26–89) and “late” (day 90–220) groups. While it is possible that there are differences between these groups based on the “wave” of the pandemic, our results suggest that there is not a clear time for expected resolution of symptoms that persist, and further study will be needed to determine long-term outcomes.

Many respondents to the survey reported lower quality of life on questions regarding limitations due to physical and emotional health, similar to a prior report indicating disrupted home, work, and social life for patients after acute COVID-19 [7]. These responses were associated with certain common symptoms (eg, fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, mental fog) more than others (eg, cough, change in smell or taste). These findings may suggest that specific symptom profiles are more significant in quality of life and may warrant particular emphasis in studies of PASC. More than half of participants with ongoing symptoms reported seeking care (or planning to seek care) for their symptoms, indicating a level of concern leading to medical attention. Prior work indicates that patients seek care at higher rates after COVID-19 than with other viral lower respiratory infections [5] and encounter challenges due to limited recognition of PASC [6, 34], and providers should be aware of the likelihood of PASC and evolving treatment guidelines.

Comparison to Prior Studies

Similar to previous studies [23, 25–27, 35, 36], this study represents a single-institution report of persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19 and finds a high rate of persistent symptoms. A novel aspect of this work is the standardized telemedicine assessment of participants by medical providers during the acute phase of illness, such that risk factors for later outcomes could be systematically analyzed. We found that the severity of symptoms at the time of the acute telemedicine visit was a significant predictor, which corroborates the prior reports relating acute illness profile to prolonged symptoms [24–26, 29]. We did not find a strong association with hospitalization, suggesting that the term “severity” may need further clarification as a symptom descriptor distinct from “disease severity” (often referring to the highest level of care, which is more strongly associated with age, sex, and medical comorbidities). The use of the physical health questions also gives more description and nuance to our findings, which is an added strength over large cohort studies of reported frequency of persistent symptoms.

We found that female gender was associated with PASC in our cohort, especially in the later group, similar to prior studies [23–25]. It has been well described that males are at higher risk for severe acute COVID-19 [37], and it has been proposed that genetic differences (including expression of Toll-like receptor 7 on the X chromosome) may account for this [38], but a mechanism relating to increased risk for PASC is not clear. There may be a common mechanism with other postinfectious syndromes: Female gender has been reported as associated with lower 6-minute walk distance in survivors of SARS [13] as well higher rates of postdengue fatigue [12] and post-Chikungunya arthralgia [11], but not consistently for post-Ebola symptoms [10].

Middle age (40–59) was significant in the adjusted model, similar to a prior report [26]. Given the strong association of illness severity (ie, risk of hospitalization and death) with age [37], hypothesized to relate to immune system changes across age groups [38], it is plausible that immune system–mediated factors during acute illness increase the risk for PASC in individuals in middle age more than other age categories.

The role of hypertension in acute COVID-19 is not clear; initially reported as a possible risk factor for severe COVID-19 (in excess in severe vs nonsevere cases) [39], it has not been shown to be a robust predictor of severity, with age–hypertension interactions even decreasing risk [37] and improved blood pressure control correlating to worse outcomes [40]. Antihypertensive medications may impact disease course, with preliminary results indicating that effects that may vary by race [41]. In this context, it is possible that there is a blood pressure (or antihypertensive) correlation with PASC, and this relationship merits further study.

Limitations

This report was conducted within a specific cohort (outpatient telemedicine clinic in Atlanta, GA, USA) early in the COVID-19 pandemic. To enter this cohort, patients must have had symptoms consistent with COVID-19 and consented to telemedicine visit; few asymptomatic (or minimally symptomatic) patients are represented, thus limiting generalizability. A related concern is the relatively low response rate to the survey and related ascertainment bias. However, the study invitation did not indicate that the survey would ask about prolonged symptoms, and we do not have reason to believe respondents would be more symptomatic than nonrespondents. A third limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study; while the groups responding at <90 days and ≥90 days appear to be similar in terms of demographic data, there is a possibility of residual confounding (such as response bias). This lessens the strength of any conclusion that symptoms present at <90 would be likely to persist beyond 90 days, which would require a longitudinal study. A final consideration interpreting our results is the uncertainty regarding the definition and grading of PASC. This was not a known entity at the time of survey design, and the questions addressed the presence of ongoing symptoms and overall health-related quality of life, but not the impact of individual symptoms on functional status. For this reason, we have analyzed the association of symptoms with functional limitations (Supplementary Table 3) as a prompt for further study.

Future study is needed to clarify the risk factors, mechanisms, duration, and subtypes of PASC. This preliminary work indicates that there are features of acute COVID-19 that may be predictive, and prospective study including objective measures (eg, inflammatory markers) as well as patient-reported measures (eg, symptom severity) may clarify this further. We found a high rate of PASC in an outpatient cohort with impact on many individuals’ quality of life, and ongoing follow-up for this important entity is warranted.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Harrell for data retrieval for this work. We also acknowledge the members of the Virtual Outpatient Management Clinic at Emory Healthcare, including faculty, staff, and administrative members of the Paul W Seavey Comprehensive Internal Medicine Clinic and the Emory at Rockbridge Primary Care clinic, as well as the physicians, nurses, and APPs who volunteered from other sites.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Georgia Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program COVID-19 Telehealth award, which is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of award number T1MHP39056 totaling US $90 625, with 0% financed with nongovernmental sources.

Disclaimer. The contents of this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the HRSA, the HHS, or the US Government.

Potential conflicts of interest. J.O. received grant funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., for a study of Monoclonal Antibodies in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Household Contacts unrelated to this work. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Hick JL, Biddinger PD. Novel coronavirus and old lessons - preparing the health system for the pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made long Covid. Soc Sci Med 2021; 268:113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020; 324:603–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. ; IVY Network Investigators; CDC COVID-19 Response Team; IVY Network Investigators. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network - United States, March-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:993–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daugherty SE, Guo Y, Heath K, et al. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2021; 373:n1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladds E, Rushforth A, Wieringa S, et al. Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20:1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havervall S, Rosell A, Phillipson M, et al. Symptoms and functional impairment assessed 8 months after mild COVID-19 among health care workers. JAMA 2021; 325:2015–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e210830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham EL, Clark JR, Orban ZS, et al. Persistent neurologic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in non-hospitalized Covid-19 “long haulers.” Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2021; 8:1073–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott JT, Sesay FR, Massaquoi TA, et al. Post-Ebola syndrome, Sierra Leone. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22:641–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Win MK, Chow A, Dimatatac F, et al. Chikungunya fever in Singapore: acute clinical and laboratory features, and factors associated with persistent arthralgia. J Clin Virol 2010; 49:111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigera PC, Rajapakse S, Weeratunga P, et al. Dengue and post-infection fatigue: findings from a prospective cohort—the Colombo Dengue Study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2021; 115:669–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngai JC, Ko FW, Ng SS, et al. The long‐term impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity and health status. Respirol Carlton Vic 2010; 15:543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam MH, Wing YK, Yu MW, et al. Mental morbidities and chronic fatigue in severe acute respiratory syndrome survivors: long-term follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:2142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188. Accessed 17 June 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doykov I, Hällqvist J, Gilmour KC, et al. ‘The long tail of Covid-19’ - the detection of a prolonged inflammatory response after a SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic and mildly affected patients. F1000Res 2020; 9:1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao YM, Shang YM, Song WB, et al. Follow-up study of the pulmonary function and related physiological characteristics of COVID-19 survivors three months after recovery. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 25:100463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paneroni M, Simonelli C, Saleri M, et al. Muscle strength and physical performance in patients without previous disabilities recovering from COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2021; 100:105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 31:100683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guedj E, Campion JY, Dudouet P, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021; 26:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennis A, Wamil M, Kapur S, et al. Multi-organ impairment in low-risk individuals with long COVID. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv 2021.01.27.21250617 [Preprint]. 30 January 2021. Available at: 10.1101/2021.01.27.21250617. Accessed 13 February 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bliddal S, Banasik K, Pedersen OB, et al. Acute and persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep 2021; 11:13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh-Messinger J, Manis H, Vrabec A, et al. The kids are not alright: a preliminary report of post-COVID syndrome in university students. medRxiv 2020.11.24.20238261 [Preprint]. 29 November 2020. Available at: 10.1101/2020.11.24.20238261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27:258–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, et al. Long COVID in the Faroe Islands - a longitudinal study among non-hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 2020; ciaa1792. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno-Pérez O, Merino E, Leon-Ramirez JM, et al. ; COVID19-ALC research group. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Incidence and risk factors: a Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect 2021; 82:378–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschtick JL, Titus AR, Slocum E, et al. Population-based estimates of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) prevalence and characteristics. Clin Infect Dis 2021; ciab408. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Keefe JB, Tong EJ, O’Keefe GD, Tong DC. Description of symptom course in a telemedicine monitoring clinic for acute symptomatic COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2021; 11:e044154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cellai M, O’Keefe JB. Characterization of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms in an outpatient telemedicine clinic. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:XXX–XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Keefe JB, Tong EJ, Taylor TH Jr, et al. Use of a telemedicine risk assessment tool to predict the risk of hospitalization of 496 outpatients with COVID-19: retrospective analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2021; 7:e25075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute COVID-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020; 370:m3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegelman JN. Reflections of a COVID-19 long hauler. JAMA 2020; 324:2031–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0240784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobson KB, Rao M, Bonilla H, et al. Patients with uncomplicated COVID-19 have long-term persistent symptoms and functional impairment similar to patients with severe COVID-19: a cautionary tale during a global pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 2021; ciab103. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodin P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat Med 2021; 27:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheppard James P, Nicholson Brian D, Joseph L, et al. Association between blood pressure control and coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes in 45 418 symptomatic patients with hypertension. Hypertension 2021; 77:846–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hippisley-Cox J, Young D, Coupland C, et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 disease with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: cohort study including 8.3 million people. Heart 2020; 106:1503–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.