Abstract

Poly(glycerol-sebacate) (PGS) is a biodegradable elastomer known for its mechanical properties and biocompatibility for soft tissue engineering. However, harsh thermal crosslinking conditions are needed to make PGS devices. To facilitate the thermal crosslinking, citric acid was explored as a crosslinker to form poly(glycerol sebacate citrate) (PGSC) elastomers. We investigated the effects of varying citrate contents and curing times on the mechanical properties, elasticity, degradation and hydrophilicity. To examine the potential presence of unreacted citric acid, material acidity was monitored in relationship to the citrate content and curing times. We discovered that a low citrate content and a short curing time produced PGSC with tunable mechanical characteristics similar to PGS with enhanced elasticity. The materials demonstrated good cytocompatibility with HUVEC cells similar to the PGS control. Our research suggests that PGSC is a potential candidate for large scale biomedical applications because of the quick thermal crosslink and tunable elastomeric properties.

Keywords: biomaterial, elastomers, poly(glycerol sebacate), citric acid, thermal crosslinking

Graphical Abstract

Poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) devices are typically made under harsh thermal crosslinking conditions. Addition of a small amount of citric acid significantly reduces the thermal crosslinking time of PGS. The Young’s modulus is easily tuned. In addition, citrate-crosslinked PGS demonstrates a faster degradation than PGS. This strategy would likely further broaden the applications of PGS.

Introduction

Poly(glycerol-sebacate) (PGS) is a biodegradable and bioresorbable elastomer that is formed through thermal crosslinking between unreacted carboxylic acids and hydroxyls on the prepolymer.[1] This elastomer exhibits stress-strain properties similar to that of vulcanized rubber.[1] Additionally, PGS has garnered attention for its tailorability of physicochemical, mechanical and biological properties.[1–5] For example, altering parameters such as molar ratio of monomers and curing temperature, substitution of hydroxyls with other molecules, or copolymerization with other monomers can manipulate the hydrophilicity, elasticity, mechanical properties and degradation for a given application.[1, 6–11] This has led to its wide applications in tissue engineering, such as cardiac patches, articular cartilage scaffolds, synthetic vascular grafts and nerve conduits.[2, 12–17] However, thermal crosslinking of the prepolymer requires harsh curing conditions, typically ranging from 120 °C to 150 °C for 24 to 144 hours.[1, 6, 7, 18] Such thermal crosslink is time and energy consuming. We are therefore seeking a method to facilitate the crosslinking without compromising the elastomer performance for biomedical applications.

To date, several studies have been conducted to impart functionalities to ease PGS crosslink for utilities. For example, acrylated PGS was designed to be photopolymerizable at ambient temperature into poly(glycerol sebacate acrylate) (PGSA) elastomer.[19] This process could be performed within minutes and would offer the advantage to crosslink the polymer in vivo by UV irradiation. Alternatively, norbornene-functionalized PGS was also designed as a photocurable prepolymer via thiol-ene click chemistry and exploited to make three-dimensional porous scaffolds using 3D printing technique.[8] In another case, PGS prepolymer was crosslinked with diisocyanate to make poly (glycerol sebacate urethane) (PGSU) elastomer at ambient temperature.[20] This material was found to be beneficial for drug delivery applications because it formed a crosslinked network without thermal or UV exposure. Given the good biocompatibility and bioresorbability of PGS, we would like to use an endogenous molecule as a crosslinker that can significantly facilitate the thermal crosslinking as well as retain the good biocompatible advantages. Citric acid is therefore selected as this type of crosslinker. Citric acid participates in human metabolic cycles and bears three carboxylic acid groups with a higher reactivity to hydroxyls compared to sebacic acid.[21–23] This molecule has been used as a cytocompatible monomer to make poly(1,8-octanediol citrate) as well as a crosslinker for many biomaterials.[22–25] Liu et al. reported citrate crosslinked PGS elastomers (PGSC) with curing temperature at 120 °C, curing times ranged from 8 to 18 h and citrate contents at 15 and 25 mol.% relative to glycerol monomer.[4] This work demonstrated that citrate indeed facilitated the crosslinking at 120 °C compared to the PGS alone under the same condition.[4, 18]

In our lab, we typically cure PGS at 150 °C for 24h to make scaffolds for utilities including synthetic vascular grafts for arteries.[6, 7, 13, 26] We would like the curing time to be as short as possible. Therefore, we investigate the PGSC elastomers made in different parameters such as curing temperature at 150 °C, curing time between 1.5 and 6h and citrate contents ranged from 4 to 8 mol.%. A lower citrate content is used in this work to avoid likely formation of acidic microdomains in the PGSC scaffolds caused by unreacted citric acid residues, which is not favored for some cell activities.[27, 28] The mechanical properties, elasticity, hydrophilicity, in vitro degradation and cytocompatibility are evaluated and compared to the PGS control. We expect this work could provide a way to ease the construction of the PGS-based devices for biomedical applications.

Methods and Materials

1. Preparation of PGSC elastomers

All chemicals were used as received. Both 40 wt./v% of PGS prepolymer solution and 1.0 M of citric acid solution were respectively prepared by dissolving PGS (Regenerez, Secant Group LLC, PA) and citric acid (Sigma Aldrich) in acetone (Pharmco, ACS grade) for use.

PGSC elastomers with citrate contents varied from 4 to 8 mol.% were prepared based on the molar ratio of citric acid to PGS repeat units. The PGSC-4%, PGSC-6%, and PGSC-8% samples were made by adding 200, 300, and 400 µl, respectively, of the 1.0 M citric acid stock solution to 3.2 ml of the 40 wt./v% PGS stock solution. The PGSC mixtures were then deposited onto rectangular modules mounted on hyaluronic acid coated glass slides. A thin layer of the hyaluronic acid coating was used to ease detachment of the crosslinked PGSC film by immersing in deionized water. The slides were evaporated in a fume hood for at least 24 h. The samples were then heated in a vacuum oven (Thermo Fisher) overnight at 60°C and approximately 30 inch Hg vacuum for further solvent evaporation. Next, the samples were crosslinked for 3 h in the vacuum oven at 150 °C and 17 inch Hg vacuum. The vacuum was adjusted at this level to prevent bubble formation likely caused by the rapid reaction of citric acid with PGS and evaporation of water byproduct. After the crosslinking was completed and the samples were cooled to room temperature, they were placed in deionized water for about 24 h for adequate wetting. The cured PGSC samples were then cautiously peeled off from the glass slides and air dried overnight. Lastly, the samples were further dried in the vacuum oven for approximately 8 h at 45 °C and 30 inch Hg vacuum.

In addition, the PGSC with citrate content fixed at 6 mol.% were respectively cured at 150°C for 1.5, 3, 4.5, and 6 h to investigate the effects of curing time on the elastomer properties. These samples are referenced as PGSC-1.5h, PGSC-3h, PGSC-4h, PGSC-6h, respectively.

To compare the different curing times of PGS without citric acid, the PGS-12h and PGS-24h controls were similarly made from the same PGS solution and then cured for comparison through the same thermal crosslinking process in the vacuum oven for 12 and 24h at 150°C, respectively.

2. Mechanical property tests

For mechanical testing, dog-bone samples were punched from the prepared PGSC samples using the Test Resource custom dog-bone cutter (3.0 cm x 0.5 cm with a neck length of 10.5 mm and width of 1.5 mm). Samples were tested on an Instron (Instron 5943) equipped with 50 N loading cell and Bluehill Universal software according to the standard method (ASTM D412). An elongation rate was set at 10 mm/min for uniaxial tensile tests. Five repeats were performed for each PGSC elastomer. The stress-strain curves were recorded to obtain average values of Young’s modulus (E), strain at fracture (%) and ultimate tensile strength (UTS) for comparison.

Elasticity for each elastomer was measured through cyclic tensile tests. The elongation rate was set at 30 mm/min and a maximum of 200 cycles was performed on each sample through a range of 5% to 50% strain. Three trials were performed to obtain an average cyclic loading number for each elastomer. Because the PGSC-6h sample could not undergo more than one cycle between 5% and 50% strain, three additional trials were conducted for this elastomer at a strain range of 5% to 20% to evaluate the elasticity.

3. In vitro degradation tests

Disc samples with 6 mm in diameter and approximately 1 mm in thickness were punched from each PGSC sample. The initial mass (M1) per disc was recorded. To each centrifuge tube, one piece of the discs was placed and 5 ml of 60 mM NaOH solution was added for degradation test (n = 4 per sample). The samples were incubated at 37°C for 6, 12, 18 and 24h, respectively. Then the samples were repeatedly washed with deionized water and freeze dried overnight. The residual mass (M2) of each disc was recorded. The degradation rate was calculated as degradation % = (M1 - M2) · 100 / M1.

4. Examination of free citric acid residues in PGSC elastomers

The PGSC samples were cut into pieces using a surgical scalpel and then doused in liquid nitrogen, followed by grinding into fine particles using a mortar and pestle. 100 mg of each sample was added to a 5-ml screw cap tube. 5.0 ml of deionized water was added to each of the samples and incubated at 37°C for 48 h to extract free CAs. Three replicates were performed for each sample. After the extracted solution was cooled down to room temperature, pH values were recorded with a pH meter.

In addition, pH measurements were recorded for a range of citric acid standard solutions. The data were used to construct a calibration curve for the relationship between free citric acid and pH level. This was further analyzed to evaluate the amount of free citric acid or its carboxylic acids residing in each sample.

5. Hydrophilicity test by water contact angle measurement

Water contact angle measurements were performed by the sessile drop method using a Rame-Hart 500 contact angle goniometer (Rame-Hart Inc., NJ) at room temperature. The PGSC polymer films were made by casting the corresponding PGS and citric acid mixture solutions on glass slides and air-dried for 24h, followed by vacuum drying at 60 °C overnight. These films were then crosslinked at 150 °C for a certain time like the conditions to make PGSC elastomers and cooled down to room temperature before the test. To each sample, 17 μl of water was dropped on the film surface and the contact angle was recorded at 50 seconds for comparison. The measurements were replicated five times on two polymer films per PGSC sample.

6. Cytotoxicity assay

In vitro cytotoxicity assay was performed by a direct contact method on PGSC coating using HUVEC cells according to the standard protocol (ISO 10993). HUVECs (passage 5) were cultured in endothelial cell growth medium containing 2% FBS and VEGF (EGM-2 BulletKit, CC-3156 & CC-4147, Lonza), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech, Manassas, VA), and 1% L-glutamine at 37 ºC with 5% CO2 until sufficient quantities were obtained.[6, 7] The cells were diluted in cell media to 1×104 cell ml−1 for use.

0.25 wt./v % of PGS prepolymer in acetone solutions containing 4, 6, and 8 mol.% citric acid were prepared respectively. 20 µl of each solution was evenly spread on a 12-mm diameter circular cover glass. A PGSC coating with a thickness of approximately 200 nm was formed on each cover glass. The slide was air-dried in a fume hood overnight and then crosslinked in a vacuum oven at 150 ºC for 3h. The coated slides were placed into a 24-well culture plate with the coating layer orientated upward. The coating was sterilized by UV exposure for 1h and subsequently washed with DPBS 1x (pH 7.4) and cell media (20 min per wash). Then 1×104 cells per well were seeded on the coating with 1.0 ml of cell media. The plate was incubated at 37 ºC with 5% CO2. After incubation for 24 and 48h, cellular metabolism (MTT assay, n=4) was evaluated by a CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The absorbance was recorded using the SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC. USA). The cells cultured in a 24-well tissue culture polystyrene plate (TCPS) and PGS coating were used as controls.

7. Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA test with post-hoc Bonferroni correction was used for statistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation (SD).

Results and Discussion

1. Citric acid facilitates PGS crosslink

PGS and citric acid mixtures are featured by a relatively quicker esterification to form crosslinks in PGSC elastomers at 150 °C under a reduced pressure within several hours (Fig. 1). In contrast, the PGS control typically requires 12 to 24 h to cure at the same condition for use.[6] This is because citric acid bears more reactive carboxylic acids for esterification compared to the sebacate-based crosslinking in the PGS.[1, 24] On the other hand, the esterification rate and crosslinking density are also dependent on the citric acid concentration. Therefore, we made PGSC elastomers with 4, 6 and 8 mol.% of citrate, namely PGSC-4%, PGSC-6% and PGSC-8%. They are used to examine the effects of citrate contents on the crosslinking and mechanical properties. Additionally, we compared the effects of curing time on the material’s properties. To this end, the citrate content is fixed at 6 mol.% and the curing time is varied from 1.5 to 6h to yield PGSC-1.5h, PGSC-3h, PGSC-4.5h and PGSC-6h for investigation. Through these studies, we would like to understand the citric acid crosslinking features and the elastomer properties compared to the PGS control for applications in tissue engineering.

Figure 1.

Chemical reaction to form citrate-crosslinked poly(glycerol sebacate) networks. Compared to the PGS alone that requires 12 to 24h for curing, citric acid significantly facilitates esterification with free hydroxyls on the PGS prepolymer to form PGSC networks.

2. Mechanical properties of PGSC elastomers

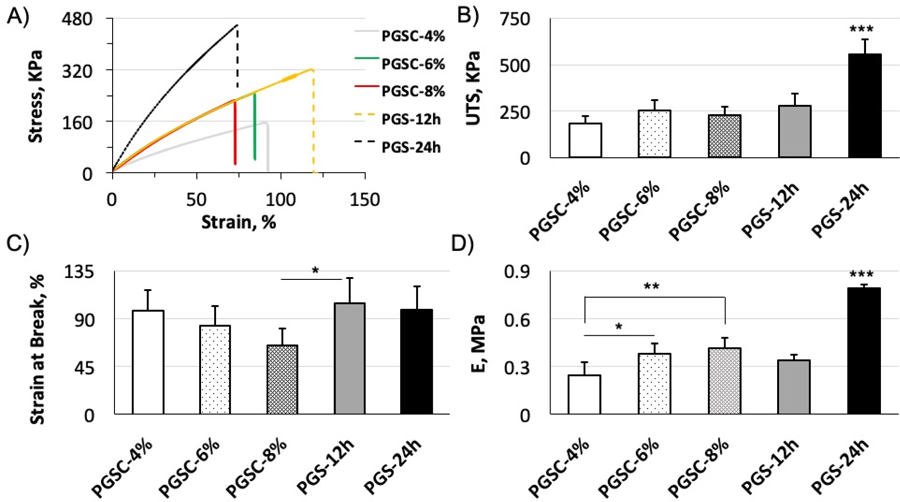

The mechanical properties and elasticity are important for elastomeric scaffolds in biomedical applications. To understand the mechanical characteristics, uniaxial tensile tests are performed to examine the strain at break, ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and Young’s modulus (E) of the PGSC elastomers relating to the citrate contents (Fig. 2). In this case, all PGSC elastomers with citrate contents varying from 4 to 8 mol.% are prepared by curing for 3 h at 150 °C under a reduced pressure. Two PGS controls cured for 12 and 24 h at the same condition are respectively prepared for comparison. Among the PGSC elastomers, a higher citrate content leads to a higher E value and a smaller strain at break (Fig. 2(C, D)). This is attributed to the elevated crosslinking densities and shorter polymer chains between the crosslinks by the increased citrate content. Such changes of the mechanical properties are typical in thermoset elastomers.[18] It is worth noting that PGSC-6% demonstrates strain at break, UTS and E comparable to the PGS-12h control, indicating the citric acid crosslinker could reduce the curing time by 9h. However, when citrate content further increases up to 8 mol.%, the E and UTS of the PGSC-8% sample remain similar to the PGSC-6% and the PGS-12h control, but are significantly lower than the PGS-24h control (Fig. 2(B, D)). On the other hand, the PGSC-8% demonstrates a reduction in strain at break but without a significant difference compared to the other two PGSC elastomers and the PGS-24h control (Fig. 2C). However, during the sample preparation process, the PGSC-8% is relatively brittle to break when peeling the sample off from glass modules under a wet condition. The brittleness is likely caused by relatively high crosslinks and citric acid residues in the PGSC-8% compared to the other compositions. These data and phenomena indicate that increase of citrate content in crosslinking appears difficult to yield a PGSC elastomer as tough as the PGS-24h control. The latter is typically used to make PGS scaffolds in our lab.[6, 7, 13, 26] We therefore further explore the effects of curing time on the PGSC elastomer properties. To this end, citrate content is fixed at 6 mol.% and curing time is varied from 1.5 to 6h to make the elastomers, namely PGSC-1.5h, PGSC-3h, PGSC-4.5h and PGSC-6h, for comparison.

Figure 2.

Tensile tests for PGSC elastomers at varying citrate contents. All PGSC samples are cured for 3 h at 150 °C. PGS-12h and PGS-24h controls are cured for 12 and 24h at the same conditions without citric acid. (A) Representative stress-strain curves. (B) UTS, p < 0.0001. (C) Strain at break, p = 0.0487. (D) E, p < 0.0001. All PGSC samples are quickly crosslinked in 3h. When citrate content increases up to 6 and 8 mol.%, the E and UTS values are comparable to the PGS-12h control. It is, however, difficult to yield a PGSC elastomer as tough as PGS-24h control by only increasing citrate content in crosslinking. * <0.05, ** <0.01, *** < 0.001. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation (n = 5).

Notably, the curing time can distinctively tune the E values of the PGSC elastomers in a short curing window (Fig. 3A, D). For example, the E value significantly elevates from 0.12 ± 0.2 MPa for the PGSC-1.5h to 1.29 ± 0.14 MPa for the PGSC-6h. This modulus range significantly surpasses the range of the PGS controls cured for 12 and 24h, 0.34 ± 0.03 MPa for the PGS-12h versus 0.79 ± 0.03 MPa for PGS-24h. Compared to the PGS-24h control, the curing time is therefore reduced by more than 18 h to make a comparable PGS derivative by citric acid crosslinking. These data further confirmed that citric acid is much more reactive to form ester linkages compared to the sebacate-based crosslinking. In addition, adjustment of the curing time is easier to control the crosslinking densities and consequently the modulus than variation of the citrate contents in the crosslinking (Fig. 2). On the other hand, we also noted that the citrate crosslinking more easily reduces the strain at break as the crosslinking density increases compared to the PGS controls (Fig. 3C). This is likely because the citric acid crosslinker is a small molecule and randomly esterified with free hydroxyls along the PGS chains. In contrast, the PGS control forms sebacate-based crosslinks typically occurred between sebacates or unreacted carboxylic acids on chain-ends and the free hydroxyls on the PGS prepolymer. In other words, a fraction of PGS prepolymers acts as macromolecular crosslinkers to esterify with free hydroxyls for crosslinking. The citric acid crosslinker is therefore more likely to form shorter polymer chains between the crosslinks compared to the PGS control, leading to a greater reduction in the strain at break in the PGSC samples as the crosslinking density increases. This crosslinking feature compromises the UTS of the PGSC elastomers due to a shorter elastic elongation compared to the PGS controls (Fig. 3B). With knowing these mechanical characteristics, we further evaluate the elastic performance of these PGSC elastomers for reversible mechanical deformations.

Figure 3.

Tensile properties of PGSC and PGS controls at varying curing times. All PGSC samples are fixed at 6 mol.% citrate but varied in curing time. (A) Representative stress-strain curves. (B) UTS, p < 0.0001. (C) Strain at break, p < 0.0001. (D) E, p < 0.0001. By varying curing time from 1.5 to 6h, E values of the PGSC elastomers are elevated from 0.12 ± 0.2 MPa for the PGSC-1.5h to 1.29 ± 0.14 MPa for the PGSC-6h. This modulus range surpasses the range of the PGS controls cured between 12 and 24h, indicating a significant reduction in curing time to mediate the modulus by citric acid crosslinking as compared to PGS alone. * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation, (n = 5).

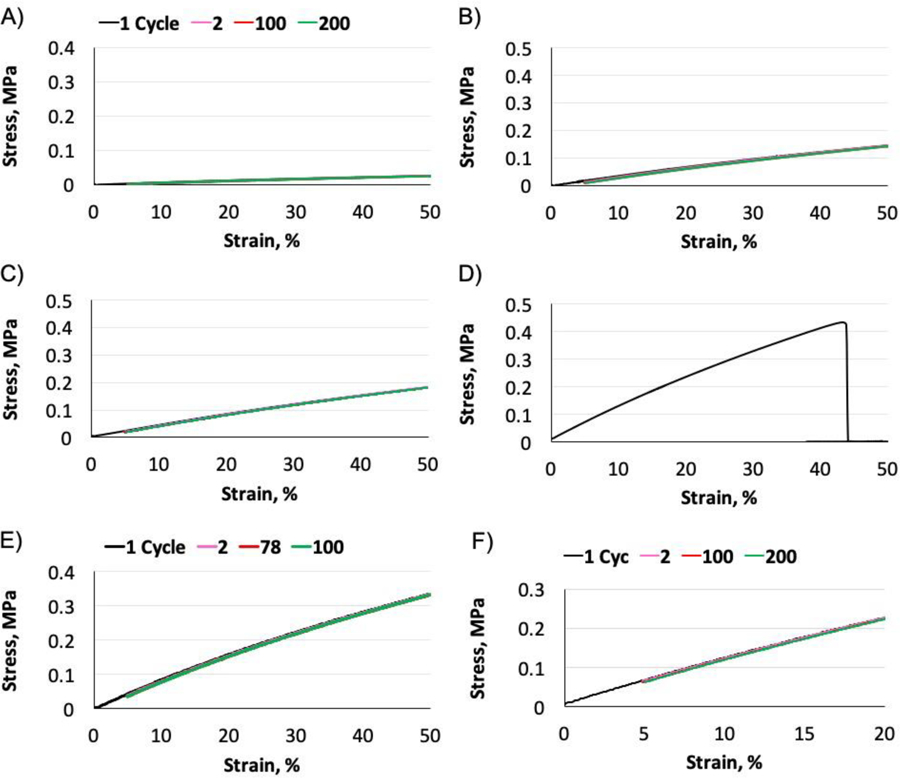

The elasticity reflects the capability to recover from elastic deformations and retain integrity of an elastomeric scaffold in a mechanically dynamic environment.[6, 7] Cyclic tensile tests are performed between 5% and 50% strain to assess the elasticity. This large deformation range is set in order to easily compare the elastic performance among the PGSC samples and the PGS control. Similarly, we first evaluate the effects of citrate compositions on the elasticity. As the citrate content increases from 4 to 8 mol.%, all PGSC elastomers could undergo reversible deformations for at least 200 cycles without break and with little hysteresis loops (Fig. 4A–C). Whereas, the PGS-24h control would break after approximately 100 cycles (Fig. 4D). Such elastic deformation profiles indicate that the PGSC elastomers possess more stable polymer networks and more effectively dissipate the exerted stress by cyclic loading compared to the PGS-24h control. Even though the PGSC-8% shows a slightly lower strain at break (Fig. 2C), this sample still demonstrates more resistance to the large deformations than the PGS-24h control (Fig. 4C, D). We would like to note that the dried PGSC-8% samples are used for cyclic tensile tests and demonstrate a similar elasticity to the other two compositions. However, the wet PGSC-8% sample is relatively brittle compared to the other samples when peeling off from the glass modules as previously mentioned. Such phenomena further confirmed that a higher fraction of unreacted citric acid or its carboxylic acids likely resides in the PGSC-8% than the other two compositions, which is detrimental to the elastic performance under wet conditions. Such negative impact on elasticity is not desired for elastomers in biomedical applications because the elastomers are typically wetted by biological fluids. Next, we compare the effects of curing time on the PGSC elasticity similarly examined between 5% and 50% strain (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Cyclic tensile tests for PGSC and PGS-24h control with strain between 5% and 50% to examine the elastic performance (n = 3). Representative plots for the cyclic stress-strain curves of (A) PGSC-4%, (B) PGSC-6%, (C) PGSC-8%, and (D) PGS-24h control. All PGSC elastomers could withstand 200 cyclic loading without break and show little hysteresis loops. Whereas, the PGS-24h control undergoes approximately 100 cycles to break at the same strain range. This comparison indicates that all PGSC elastomers with the three different citrate contents demonstrate more durable network structures to dissipate the cyclic loading stress.

Figure 5.

Cyclic tensile tests for the PGSC and PGS-24h control between 5% and 50% strain (n = 3). The curing time for the PGSC samples varies from 1.5 to 6h. Representative plots for the cyclic stress-strain curves of (A) PGSC-1.5h, (B) PGSC-3h, (C) PGSC-4.5h, (D) PGSC-6h and (E) PGS-24h control. (F) The elasticity of the PGSC-6h is further examined between 5% and 20% strain. The PGSC samples cured between 1.5 and 4.5h are more durable to withstand the large deformations compared to the PGS-24h control. When increasing the curing time up to 6h, the PGSC-6h still demonstrates robust elasticity between 5% and 20% strain. These hysteresis test results indicate the curing time varied from 1.5 to 6h are suitable to construct PGSC elastomers for soft tissue engineering applications.

As we already knew from the changes of mechanical properties, increase of curing time can efficiently elevate the crosslinking densities and accordingly modulate the modulus of the elastomers in a narrow curing window (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the strain at break is also significantly compromised as the curing time increases up to 6h (Fig. 3C). The reduction of strain at break would likely compromise the ability for large deformations too. Compared to the PGS-24h control that withstands approximately 100 cyclic loadings (Fig. 5E), all PGSC elastomers with curing time between 1.5 and 4.5h could undergo at least 200 cycles without break and with little hysteresis loops (Fig. 5A–C). The hysteresis test results indicate that the elastomers of PGSC-1.5h to PGSC-4.5h are more stable to tolerate large deformations than the PGS-24h control, although the PGSC-3h and PGSC-4.5h already show a slightly lower strain at break compared to the PGS-24h control (Fig. 3C). In contrast, further increase of the curing time up to 6h reduces the strain at break to 34.8 ± 6.6% in the PGSC-6h (Fig. 3C). The PGSC-6h is only able to undergo one deformation between 5% and 50% strain because the range exceeds its maximal elongation (Fig. 5D). We therefore further examine the elasticity of the PGSC-6h between 5% and 20% strain and find that this elastomer is similarly robust to undergo at least 200 cycles of deformations with little hysteresis loops (Fig. 5F). Most soft tissues including ligaments and blood vessels undergo mechanical deformations within 20% strain.[29, 30] Therefore, the PGSC cured for 6 h is still suitable to construct elastomeric scaffolds for soft tissue engineering.

Through above discussion, the range of achievable mechanical characteristics can be finely and easily tuned through adjustment of either citrate contents or curing time in a narrow window. Previous studies have reported to alter the mechanical properties of PGS through the variation of polymer composition, curing times and curing temperatures in a relatively harsh condition.[2, 3, 18, 31] For example, curing the PGS alone at 120 ºC and 10 mTorr for 42 and 114h could adjust the elastic modulus from approximately 0.3 to 1.5 MPa.[18] In our case, addition of appropriate amount of citric acid to the PGS curing process provides an efficient method to modulate the elastomer mechanics with a significantly shorter curing time and yield comparable PGS derivatives for applications in tissue engineering and others. Although the citrate crosslinked PGS would compromise the elastic elongation and UTS to certain extent, all PGSC elastomers, including the PGSC-6h, have demonstrated robust elasticity if the deformations are constrained within 20% strain, indicating suitability for soft tissue engineering applications. In addition, compared with the citrate content to adjust the elastomer mechanics, our studies revealed that variation of curing time in a narrow window, e.g. 1.5 to 6h, could more efficiently mediate the Young’s modulus of the PGSC elastomers from 0.12 ± 0.2 MPa to 1.29 ± 0.14 MPa. Such citric acid facilitated thermal crosslink significantly shortens the curing time in constructing PGS-based devices compared to the conventional PGS thermal crosslinking.

Hydrophilicity of PGSC elastomers

Citric acid is a hydrophilic molecule bearing three carboxylic acids and one secondary hydroxyl.[22] Therefore, addition of citric acid to crosslink PGS would be expected to enhance the hydrophilicity and consequently the degradation of the resultant elastomers. Based on the above discussion, variation of the curing time is more efficient to adjust the modulus and form relatively tough PGSC elastomers compared to different citrate contents in crosslinking. Because PGSC-8% is relatively brittle when soaked in water, we deemed it unsuitable for biomedical applications. Therefore, we decided to test the hydrophilicity with citrate below 8 mol.%, as we have stated in section 2. All PGSC samples with different citric acid contents were crosslinked for 3h. The PGSC-6% sample is the same as the PGSC-3h (Please see the experimental section). Given that PGSC-6% contains a higher citrate content than the PGSC-4%, we therefore believe the hydrophilicity change of the PGSC samples with different curing times could reflect the overall hydrophilicity of these elastomers. In addition, we noted that the PGSC-1.5h sample is slightly adhesive and relatively easy to absorb moisture. This interfered with the evaluation of the hydrophilicity. Therefore, we mainly compare the hydrophilicity of PGSC cured between 3 and 6h with the PGS control, namely PGSC-3h, PGSC-4.5h and PGSC-6h elastomers versus the PGS-24h control (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Water contact angle measurements to evaluate the hydrophilicity among the PGSC elastomers with curing time varied from 3 to 6h versus the PGS-24h control. All PGSC elastomers show a significantly lower water contact angle compared to the PGS-24h control, indicating that the presence of a certain amount of citrate increases the hydrophilicity. p < 0.0001. ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation, (n = 5).

As expected, all PGSC elastomers are more hydrophilic than the PGS-24h control with water contact angle below 66.3 ± 1.2 degree. By increasing the curing time from 3 to 6h, the water contact angle slightly elevates from 58.4 ± 3.1 degree for the PGSC-3h to 61.3 ± 1.7 degree for the PGSC-6h without significant differences among them. On the other hand, given the significantly higher Young’s modulus of the PGSC-6h (1.29 ± 0.14 MPa) than the PGS-24h control (0.79 ± 0.03 MPa) (Fig. 3D), it reflects more hydroxyls are consumed by citric acid crosslinking in the PGSC-6h than that of the PGS-24h. It is known that the hydrophilicity of the PGS-24h is dominated by free hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. Therefore, we deduce that the increased hydrophilicity in the PGSC samples is mainly contributed by citrate components, including citrate-based carbonyl groups, hydroxyls and some unreacted carboxylic acids. Unreacted citric acid residues are possible but the effects are minimal according to the difference of the water contact angles among these PGSC samples (Fig. 6). The hydrophilicity of a biomaterial is important because it affects a range of properties, including adhesion of proteins, cell infiltration, adhesion and proliferation as well as inflammatory reactions and biodegradation.[32, 33] In our case, since the citric acid-based carboxylic acids are likely present in the PGSC samples to elevate the hydrophilicity, we therefore examine the impacts on the pH levels, degradation and cytocompatibility of these PGSC elastomers in following sections.

Material acidity affected by carboxylic acid residues

Citric acid is a tricarboxylic acid with pKa values of 3.14, 4.77 and 6.39 compared with the sebacic acid with pKa values of 4.72 and 5.45.[21, 34] After crosslinking with PGS, the likely presence of free citric acids and unreacted carboxylic acids would affect the acidity of the materials. In contrast, the acidity of the PGS is dependent on the unreacted carboxylic acids from sebacic acid and the effects on biocompatibility of PGS has been well established both in vitro and in vivo.[1, 6, 7, 13, 26] Given the difference of the pKa values between them, measurements of the pH levels could reflect the unreacted carboxylic acids relating to the added citric acid contents and the curing time. To this end, 100 mg of each ground sample are extracted in 5.0 ml of deionized water for 48 h to reach an equilibrium ionization for pH measurement. In addition, a calibration curve is built up from a series of known citric acid-based carboxylic acid concentrations to evaluate the unreacted carboxylic acids according to the measured pH value (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

pH measurements of the solutions extracted from the PGSC samples and PGS controls. (A) PGSC samples crosslinked with citrate contents from 4 to 8 mol.%, p < 0.0001. (B) PGSC with 6 mol.% citrate and curing time varied from 3 to 6h, p < 0.0001. (C) Calibration curve of pH against the citric acid-based carboxylic acid concentrations. * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation, (n = 3).

When the curing time is fixed at 3h, the PGSC samples with citrate contents varied from 4% to 8% show no significant difference in the pH (approximately 3.72 ± 0.010 to 3.56 ± 0.014) (Fig. 7A). This result indicated that most citric acid were quickly esterified with hydroxyls and the unreacted carboxylic acids ranged from approximately 0.79 and 1.27 mmol/L according to the calibration curve (Fig. 7C). We assume the measured pH values in these PGSC samples are dominated by the unreacted citric acid-based carboxylic acids. Therefore, more citric acids form more crosslinks with slightly more unreacted carboxylic acids after curing for 3h. This is consistent with the change of Young’s modulus versus the citrate contents (Fig. 2). On the other hand, all of the three PGSC samples are significantly more acidic than both the PGS-12h (pH about 4.25 ± 0.061) and PGS-24h (pH about 5.29 ± 0.16) controls, confirming the presence of unreacted citric acid-based carboxylic acids in them (Fig. 7A). Further, when the citrate content is fixed at 6 mol.%, the increased curing time from 3 to 6h results in a pH level close to the PGS-12h control, indicating most citric acids are esterified over 6h curing with little carboxylic acids left (Fig. 7B). We would like to note that we aim to assess the unreacted carboxylic acids from the citric acid crosslinker using the calibration curve. Identifying the exact citric acid-based carboxylic acid residues in these PGSC samples are difficult because of the presence of both citric acid and sebacic acid-based carboxylic acids and their multiple pKa values. Nonetheless, the measurement of the pH levels in these materials can provide information on the material acidity and carboxylic acid residues, which will potentially affect the surface properties for cell attachment, infiltration and proliferation for applications.[35]

In addition, the amount of unreacted carboxylic acids is easily controlled by variation in the curing time. Using the calibration curve, there are approximately 0.29 mmol/L of unreacted carboxylic acids in the PGSC-6h and 0.84 mmol/L in the PGSC-3h. An additional 3h of curing time results in a 65% reduction in the unreacted carboxylic acids. Since a large reduction can be achieved in such a short period of time, the carboxylic acids can be finely tuned with slight changes in the curing time. This feature can likely modulate the surface properties of the PGSC materials for utilities.

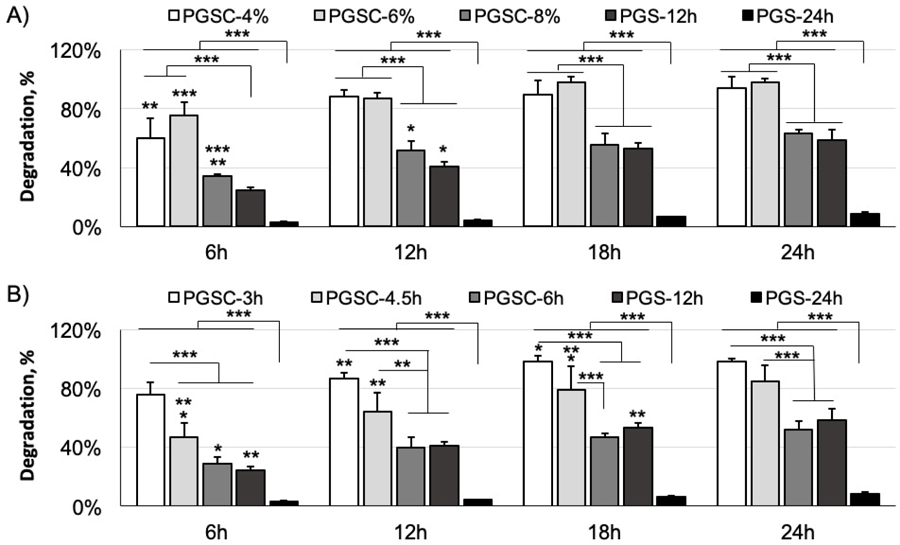

In vitro degradation study

We performed an accelerated degradation of the materials in 60 mM NaOH solution at 37 °C against incubation time (Fig. 8). All disc samples become thinner with incubation time in the basic solution mainly through a surface erosion mechanism, which is similar to a prior report.[18] Generally, the degradation rate is proportional to the hydrophilicity but inverse to the crosslinking density. These two aspects synergistically affect the PGSC degradation as compared to the PGS controls. The PGS controls drastically reduce the degradation rate as the curing time increases from 12 to 24h to form more crosslinks (PGS-12h versus PGS-24h). Similarly, the PGSC samples also demonstrate a slower degradation as the crosslinking density increases through either a higher citrate content in crosslinking or increase of the curing time (Fig. 8A, B). However, the overall degradation rate of all PGSC samples are significantly higher than the PGS-24h control, even though the PGSC-6h possesses a higher crosslinking density than the PGS-24h control as the mechanical property tests exhibited (Fig. 3). This is because all PGSC samples are more hydrophilic than the PGS-24h control (Fig. 6), which facilitates water molecule penetration and hydrolysis of the ester bonds in the PGSC samples. Another factor is likely that the citrate-based ester bonds are easier to hydrolyze than the sebacate-based ones. The more acidity in PGSC samples is also likely to promote the hydrolysis compared to the PGS controls.

Figure 8.

Accelerated degradation of the PGSC elastomers as a function of time in 60 mM NaOH solution at 37 °C. (A) PGSC samples with varying citrate contents. p < 0.0001. (B) PGSC samples with different curing time. p < 0.0001. The PGS cured for 12 and 24h are used as controls. The degradation rate is proportional to the hydrophilicity but inverse to the crosslinking density. These two aspects synergistically affect the PGSC degradation as compared to the PGS controls. * < 0.05, ** < 0.01 and *** < 0.001. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation, (n = 4).

Some researchers performed degradation tests in a different condition compared to ours and therefore showed different results.[4] In our case, we performed an accelerated degradation in 60 mM NaOH solution at 37 °C to quickly examine the different degradation profiles among the PGSC and PGS control samples over 24h. We did not examine the likely uncrosslinked chains in these samples because we typically directly use crosslinked PGS scaffolds after washing in deionized water and sterilization.[13] Since both the PGSC and PGS samples did not obviously swell in the NaOH solution during the degradation tests, the degradation data could reflect their different hydrolyses features across the degradation test, unlikely being dominated by dissolution of the uncrosslinked chains.

Depending on the applications, the polymer degradation timeline can drastically range; soft tissue engineering may require polymers to last an appropriate duration for host cell remodeling.[36] Our PGS scaffolds such as synthetic grafts cured from 24h are degraded in vivo in about 2 weeks post-implantation.[6, 13, 26] For a longer degradation window, other studies have demonstrated longer curing times (44 to 114h) could result in degradation over a month.[18] In a recent study, we also reported a fatty acid-functionalized PGS to inhibit the degradation that could last for 4 to 12 weeks in vivo for a more efficient graft remodeling by host cells.[7, 26] In this case, the PGSC demonstrates a facilitated degradation in vitro. Variations of either a low amount of the citric acid crosslinker or a short curing window could readily adjust the mechanics of the PGSC elastomers similar to the characteristics of the PGS control. This strategy thus adds an additional controllable parameter to tailor the degradation characteristics to a specific application. In vivo degradation would involve water molecules and protease absorption, catalyzed ester cleavages, inflammatory responses and reactive oxygen species, which are significantly different with the in vitro conditions.[18, 37, 38] We anticipate the in vitro degradation results would give some guidance on selecting the appropriate PGSC composition and curing parameters for utilities. Further studies are required for a better understanding of in vivo degradation of the PGSC elastomers.

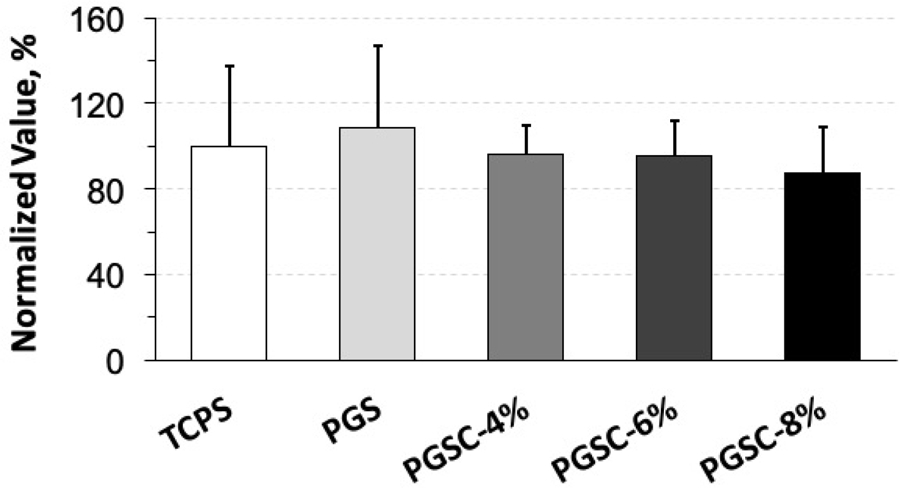

In vitro cytocompatibility

Biocompatibility of the PGS has been well established both in vitro and in vivo.[6, 7, 13, 26] Citric acid undergoes a metabolic pathway called Krebs cycle to generate energy in animals.[22] Therefore, the PGSC materials should retain good biocompatibility too. We examined the cytocompatibility of the materials on HUVEC cells over 48h by MTT assay (Fig. 9). As the citrate contents vary from 4 to 8 mol.% in the crosslinking, the PGSC samples demonstrate a slight decrease of the normalized MTT assay values compared to the PGS and TCPS controls but without significant difference. The cellular metabolism remains above 87 ± 21% among all of these PGSC samples, indicating little difference of the cytocompatibility among these PGSC materials and the PGS control.

Figure 9.

MTT assay to evaluate the cytocompatibility of PGSC elastomers using HUVEC cells. The cells are incubated on the PGSC layers over 48 h. The normalized MTT values of all PGSC samples remain similar to the PGS and TCPS controls, indicating the cytocompatibility is good as the PGS control. ns, p = 0.8083. p < 0.05 is considered significantly different. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation, (n = 4).

We mainly examined the cytocompatibility of the PGSC with citrate contents ranging from 4 to 8 mol.%. The data can also reflect the outcomes of all PGSC elastomers with curing time ranging from 3 to 6h and the citrate content fixed at 6 mol.%. With respect to biocompatibility, because PGSCs demonstrate a significantly quicker degradation than the PGS controls (Fig. 7), further in vivo studies are needed to give a more holistic view of PGSC for biomedical applications.

Conclusion

PGS has shown promise in the biomedical industry. Despite its potential, the high curing temperature and long curing time hinder the adoption of PGS based devices. The derivative of PGS by a small amount of citric acid crosslinker can achieve a broad range of characteristics similar to those of the PGS, but in a fraction of the curing time. In addition, citrate crosslinked PGS also enhances the hydrophilicity and yields a faster degradation. These PGS derivatives retain the good cytocompatibility of PGS. These PGS derivatives expand the potential application of PGS.

Acknowledgements:

This project is supported by NIH grant R01HL089658. This work made use of the Cornell Center for Materials Research Shared Facilities which are supported through the NSF MRSEC program (DMR-1719875). We thank Secant Group LLC for supplying the PGS.

References:

- [1].Wang Y, Ameer GA, Sheppard BJ, Langer R, Nature Biotechnology 2002, 20, 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rai R, Tallawi M, Grigore A, Boccaccini AR, Progress in Polymer Science 2012, 37, 1051. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kemppainen JM, Hollister SJ, J Biomed Mater Res A 2010, 94, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liu Q, Tan T, Weng J, Zhang L, Biomed Mater 2009, 4, 025015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kerativitayanan P, Gaharwar AK, Acta biomaterialia 2015, 26, 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ding X, Wu YL, Gao J, Wells A, Lee K, Wang Y, J Mater Chem B 2017, 5, 6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ding X, Chen Y, Chao CA, Wu YL, Wang Y, Macromolecular bioscience 2020, 2000101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [8].Yeh Y-C, Ouyang L, Highley CB, Burdick JA, Polym. Chem 2017, 8, 5091. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jia Y, Wang W, Zhou X, Nie W, Chen L, He C, Polymer Chemistry 2016, 7, 2553. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wilson R, Divakaran AV, K. S, Varyambath A, Kumaran A, Sivaram S, Ragupathy L, ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yeh YC, Highley CB, Ouyang L, Burdick JA, Biofabrication 2016, 8, 045004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zaky SH, Lee KW, Gao J, Jensen A, Close J, Wang Y, Almarza AJ, Sfeir C, Tissue Eng Part A 2014, 20, 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee KW, Gade PS, Dong L, Zhang Z, Aral AM, Gao J, Ding X, Stowell CET, Nisar MU, Kim K, Reinhardt DP, Solari MG, Gorantla VS, Robertson AM, Wang Y, Biomaterials 2018, 181, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jeffries EM, Allen RA, Gao J, Pesce M, Wang Y, Acta biomaterialia 2015, 18, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Allen RA, Wu W, Yao M, Dutta D, Duan X, Bachman TN, Champion HC, Stolz DB, Robertson AM, Kim K, Isenberg JS, Wang Y, Biomaterials 2014, 35, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rai R, Tallawi M, Barbani N, Frati C, Madeddu D, Cavalli S, Graiani G, Quaini F, Roether JA, Schubert DW, Rosellini E, Boccaccini AR, Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2013, 33, 3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Singh D, Harding AJ, Albadawi E, Boissonade FM, Haycock JW, Claeyssens F, Acta biomaterialia 2018, 78, 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pomerantseva I, Krebs N, Hart A, Neville CM, Huang AY, Sundback CA, J Biomed Mater Res A 2009, 91, 1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nijst CLE, Bruggeman JP, Karp JM, Ferreira L, Zumbuehl A, Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pereira MJ, Ouyang B, Sundback CA, Lang N, Friehs I, Mureli S, Pomerantseva I, McFadden J, Mochel MC, Mwizerwa O, Del Nido P, Sarkar D, Masiakos PT, Langer R, Ferreira LS, Karp JM, Adv Mater 2013, 25, 1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Soltoft-Jensen J, Hansen F, Emerging technologies for food processing 2015, ISBN: 0–12-676757–2, 387.

- [22].Ciriminna R, Meneguzzo F, Delisi R, Pagliaro M, Chem Cent J 2017, 11, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Djordjevic I, Choudhury NR, Dutta NK, Kumar S, Polymer International 2011, 60, 333. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang J, Webb AR, Pickerill SJ, Hageman G, Ameer GA, Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Halpern JM, Urbanski R, Weinstock AK, Iwig DF, Mathers RT, von Recum HA, J Biomed Mater Res A 2014, 102, 1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Fu J, Ding X, Stowell CET, Wu YL, Wang Y, Biomaterials 2020, 257, 120251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Seifu DG, Purnama A, Mequanint K, Mantovani D, Nat Rev Cardiol 2013, 10, 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Higgins S, Solan AK, Niklason LE, J Biomed Mater Res 2003, 67A, 295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Humphrey JD, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 2003, 459, 3. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ding X, Gao J, acharya a., Wu Y-L, Little SR, Wang Y, ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2020, 6, 852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chen QZ, Bismarck A, Hansen U, Junaid S, Tran MQ, Harding SE, Ali NN, Boccaccini AR, Biomaterials 2008, 29, 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Menzies KL, Jones L, Optometry and Vision Science 2010, 87, 387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Faucheux N, Schweiss R, Lutzow K, Werner C, Groth T, Biomaterials 2004, 25, 2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bretti C, Crea F, Foti C, Sammartano S, J. Chem. Eng. Data 2006, 51, 1660. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li B, Ma Y, Wang S, Moran PM, Biomaterials 2005, 26, 4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lyu S, Untereker D, Int J Mol Sci 2009, 10, 4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang Y, Kim YM, Langer R, J Biomed Mater Res 2003, 66A, 192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ding X, Gao J, Wang Z, Awada H, Wang Y, Biomaterials 2016, 111, 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]