Abstract

Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus are gram negative bacteria that can produce several secondary metabolites, including antimicrobial compounds. They have a symbiotic association with entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs). The aim of this study was to isolate and identify Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus species and their associated nematode symbionts from Northeastern region of Thailand. We also evaluated the antibacterial activity of these symbiotic bacteria. The recovery rate of EPNs was 7.82% (113/1445). A total of 62 Xenorhabdus and 51 Photorhabdus strains were isolated from the EPNs. Based on recA sequencing and phylogeny, Xenorhabdus isolates were identified as X. stockiae (n = 60), X. indica (n = 1) and X. eapokensis (n = 1). Photorhabdus isolates were identified as P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii (n = 29), P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis (n = 18), P. luminescens subsp. laumondii (n = 2), and P. asymbiotica subsp. australis (n = 2). The EPNs based on 28S rDNA and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) analysis were identified as Steinernema surkhetense (n = 35), S. sangi (n = 1), unidentified Steinernema (n = 1), Heterorhabditis indica (n = 39), H. baujardi (n = 1), and Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3 (n = 3). Antibacterial activity showed that X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) extract inhibited several antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on mutualistic association between P. luminescens subsp. laumondii and Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3. This study could act as a platform for future studies focusing on the discovery of novel antimicrobial compounds from these bacterial isolates.

Introduction

Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus are motile, gram-negative rods, facultative anaerobes, non-sporeforming, oxidase-negative, and chemoorganotrophic heterotrophs with respiratory and fermentative metabolism. These bacteria symbiotically inhabit the intestine of the infective juvenile (IJ) stage of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) belonging to the Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae families [1]. The IJs of EPNs enter the digestive tract of the insect larvae, penetrate the hemocoel of the insect host, and release the bacteria into the hemolymph. Together, the IJs and bacteria rapidly kill the insect larvae within 24–48 h [2]. Otherwise, the nematodes or bacteria themselves make significant contributions to pathogenesis within the insect [3–5].

Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus can produce several secondary metabolites, including insecticidal and antimicrobial compounds, such as benzylideneacetone, phenethylamines, indole, xenocoumacins, 3,5-dihydroxy-4-isopropylstilbene [6, 7], GameXPeptide, xenoamicin, xenocoumacin, mevalagmapeptide phurealipids derivatives, and isopropylstilbene [8]. Several studies on the bioactive compounds of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus against various microorganisms have demonstrated their antibacterial [9], antimicrobial [10], and antiparasitic effects [11].

Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus have been isolated from across the world, including Europe, Australia, America, and Asia. Currently, 29 species of Xenorhabdus and 20 species of Photorhabdus [12] have been reported. Over 90 confirmed species of EPNs [13] have been described from a variety of ecological habitats throughout the world, except Antarctica [14]. In Thailand, six species of Xenorhabdus: X. stockiae, X. miraniensis, X. ehlersii, X. vietnamensis, X. indica, and X. japonica [15–18], and three species of Photorhabdus: P. luminescens, P. asymbiotica subsp. australis, and P. temperata subsp. temperata have been reported [8, 17, 19, 20]. Also, at least 11 species of EPNs have been reported from several regions of the country, including Steinernema siamkayai, S. surkhetense, S. websteri (synonym S. carpocapsae), S. scarabiae, S. kushidai, S. minutum, S. khoisanae, Heterohabditis indica (synonym H. gerrardi), H. baujardi (synonym H. somsookae), H. bacteiophora, and H. zealandica [8, 15, 17, 18, 20–22]. However, there is limited information regarding EPNs and their symbiotic bacteria from Northeastern Thailand.

The objectives of this study to isolate and identify EPNs and their symbiotic bacteria Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus from Northeastern Thailand; we also analyzed their phylogenetic diversity. The antibacterial activity of the extracts of the identified Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus strains against antibiotic-resistant bacteria was also evaluated using the disk diffusion method, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), and minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC). This study will provide information at the molecular level that can assist in taxonomy of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates, and their EPN hosts from Thailand. These bacteria may serve as a resource for discovery a novel bioactive compound.

Materials and methods

Collection of soil samples

A total of 1,445 soil samples from 289 soil sites were collected from nine provinces in Northeastern Thailand. All soil sites belonged to public areas and no specific permission was required. For each soil site, five soil samples were randomly taken from an area of approximately 10 m2 and at a depth of 10–15 cm using a spade. Approximately 500 g of each soil sample was placed in a plastic bag. Site location, latitude, longitude and altitude, soil temperature, pH, and moisture were recorded. Soil samples were maintained at 25–30°C during transportation to the Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medical Science, Naresuan University.

Isolation and identification of entomopathogenic nematodes

The IJs of EPNs were isolated by the baiting technique as previously described [17]. For each soil sample, five larvae of Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth) were placed on top of the soil sample stored in a plastic container. Subsequently, the container was covered with a lid, and it was turned upside down to let the larvae move into the soil. It was incubated in dark at 30°C for 5 days. The dead larvae of G. mellonella were collected from the soil samples and then larval cadavers were placed on a White trap [23] to allow the IJs to emerge. The IJs were collected in a tissue culture flask, cleaned with sterile distilled water, and stored at 15°C.

EPNs were identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which was performed in an Applied Biosystems thermal cycler (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and sequencing of a partial region of 28S rDNA for Steinernema and the internal transcribe spacer (ITS) for Heterorhabditis. The primers used were as follows: 539_F (5’GGATTTCCTTAGTAACTGCGAGTG-3’) and 535_R (5’–TAGTCTTTCGCCCCTATACCCTT-3’) for Steinernema; 18S_F (5’-TGATTACGTCCCTGCCCTTT-3’) and 26S_R (5’-TTTCACTCGCCGTTACTAAGG-3’) or TW81_F (5’-GTTTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGC-3’) and AB28_R (5’-ATATGCTTAAGTTCAGCGGGT-3’) for Heterorhabditis. The PCR reagents and conditions were as described in a previous study [17]. The PCR products were checked on 1.2% agarose gel by electrophoresis.

Isolation and identification of symbiotic bacteria

The infected dead larvae of the greater wax moth were surfaced sterilized with 95% ethanol before dissection. The hemolymph was collected by a sterile loop, and then streaked onto a nutrient bromothymol blue agar (NBTA). The plate was incubated at 28°C in dark for 4 days. The bacterial isolates (blue or green colonies) were selected and stored in LB broth containing 50% glycerol (v/v) at -80°C.

The genomic DNA of 113 isolates of the symbiotic bacteria was extracted with the Genomic DNA Mini Kit (Blood/Cultured cell) (Geneaid Biotech Ltd., Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A partial sequence of recA gene was amplified from the genomic DNA by PCR using forward and reverse primers (5’-GCTATTGATGAAAATAAACA-3’ and 5’-RATTTTRTCWCCRTTRTAGCT-3’) to obtain an 890 bp amplicon (24). The PCR mixture (50μL) consisted of 10 μL of 5X buffer, 7 μL of 25 mM MgCl2, 1 μL of 200 mM dNTPs, 2 μL of 5 mM of each primer, 0.5 μL of 5 unit Taq polymerase (Sigma, USA), 2.5 μL of DNA template, and 25 μL distilled water. PCR cycling parameters for the recA gene of Xenorhabdus were as follows: an initial denaturing step of 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 50°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR parameters for Photorhabdus were as follows: an initial denature step of 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing temperature of 50°C for 45 s and extension of 72°C for 1.5 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were checked on 1.2% agarose gel by electrophoresis and purified using the Gel/PCR DNA Fragment Extraction Kit (Geneaid Biotech Ltd., Taiwan).

PCR for 16S rDNA, gyrB, dnaN gltX, and infB

recA analysis revealed that one Xenorhabdus (KK9.1_TH) isolate had lower than 96% similarity in the BLASTN search; this isolate was selected for further analysis, and sequencing of its additional nucleotide regions, including 16S rDNA, gyrB, dnaN, gltX, and infB, was performed. Primers and PCR reagents used for 16S rDNA, gyrB, dnaN gltX, and infB were as previously described [24, 25]. PCR was performed in a Biometra TOne Thermal cycler (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). The PCR products were verified on 1.2% agarose gel by electrophoresis.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The sequencing of the PCR products was done at Macrogen Inc. Service (Korea) (http://www.macrogen.com). The nucleotide sequences were edited and merged with the SeqManTMII software (DNASTAR Inc., Wisconsin, USA). The recA sequences of the bacteria from the present study were deposited in the NCBI database under the Genbank accession numbers KY809276 to KY809337, MT160765 to MT160768, and MT158222 for Xenorhabdus spp., and KY809338 to KY809388 for Photorhabdus spp. The 28S rDNA sequences of Steinernema isolates were deposited in the NCBI database under the Genbank accession numbers KY809389 to KY809425, and the ITS sequences of the Heterorhabditis isolates were deposited in NCBI database under the Genbank accession numbers KY809426 to KY809468.

The consensus sequences of each species were used for multiple sequence alignment using Clustal W [26] in the MEGA software version 6.0 [27]. Species identification was performed using BLASTN (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Similarity ≥ 97% was considered as the same species. The known nucleotide sequences of EPNs and their symbiotic bacteria in the NCBI database were downloaded and used as the reference species. For EPNs, maximum likelihood (ML) trees of the entire gene (28S rDNA, and ITS) were constructed based on Tamura 3-parameter with 1,000 bootstrap replicates model using MEGA 6.0 software [27]. For symbiotic bacteria, maximum likelihood (ML) trees of the entire gene (16S rDNA, recA, gyrB, dnaN gltX, and infB) and the concatenation of truncated sequences of recA, gyrB, dnaN gltX, and infB were constructed based on Tamura 3-parameter model using MEGA 6.0 software [27]. Also neighbor-joining trees (NJ) were constructed based on a Kimura 2-parameter with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA 6.0 software [27]. Bayesian analysis was performed based on Markov chain Monte Carlo method in MrBayes v3.2 [28].

Preparation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

Fifteen strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including Acinetobacter baumannii (four clinical strains), Escherichia coli (two clinical strains), E. coli ATCC35218, Klebsiella pneumoniae (two clinical strains), K. pneumoniae ATCC700603, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC51299, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus (two clinical strains), and S. aureus ATCC20475, were used as the pathogens for testing the antibacterial activity of the extracts of the symbiotic bacteria. These bacteria were streaked on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. A single colony was resuspended in 0.85% sodium chloride (NaCl), and the turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standards. Then, 100 μL of the bacterial suspension was swabbed on MHA plate for disk diffusion test [29].

Screening of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates

Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates were cultured on NBTA at 28°C in dark for four days. A single colony from each isolate was transferred to a 15-ml tube containing 5 mL of LB broth and incubated at room temperature for 48 h under shaking conditions. A paper disk (6 mm with diameter) with a 20 μL drop of the whole cell culture was placed on MHA plated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The plates were placed in an incubator at 37°C for 24 h. The inhibition zone (clear zone) was checked and measured (millimeter). The most effective isolates of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus were selected for crude compound extraction.

Bacterial extracts

A single colony of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus on NBTA medium was inoculated to 1000 mL flask containing 500 mL of LB. The culture flask was shaken at 180 rpm for 72 h. The bacteria cultured was added with 1000 mL ethyl acetate and mixed well. All solvents were removed from bacterial extracts by a rotary vacuum evaporator (Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to bacterial extracts to make a final concentration of 500 mg/mL and stored at -20°C until used.

Disk diffusion method

Cultured drug resistant bacteria were spread on MHA agar. A sterile 6 mm disc was put onto MHA agar plate and then 10 μL of each bacterial extract was dropped onto a sterile disc. Negative control was DMSO and Positive control was antibiotic disks. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The inhibition zone was measured in millimeter. The most effective results of bacterial extracts were further evaluated by MIC and MBC.

MIC and MBC assays

Bacterial extracts were diluted in two-fold serial dilutions in a 96-well micro titer plate. The suspension of drug resistant bacteria (1 × 108 cell/ml) was added into each well and mixed well. Cultured drug resistant bacteria, cultured drug resistant bacteria mixed with DMSO, and sterile Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth were used as controls. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. No visible growth of drug resistant bacteria in the well was considered as MIC. In addition, 10 μL from each well from the MIC assay was dropped onto MHA plates. The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The lowest concentration of bacterial extract without growth of drug resistant bacteria was considered as MBC.

Results

Isolation of EPNs

A total of 1,445 soil samples from 289 sites were collected from the Northeastern region of Thailand, including Kalasin [30], Khon Kaen, Chaiyaphum, Nakhon Ratchasima, Maha Sarakham, Loei, Nong Khai, Nhong Bua Lamphu, and Udon Thani provinces. The recovery rate of EPNs was 7.82% (113/1,445) of the total soil samples collected. We isolated 62 strains belonging to Xenorhabdus spp. and 51 strains belonging to Photorhabdus spp. from the EPNs (Table 1). Most of the soil samples were positive with only one of the two genera of EPNs (Steinernema spp. and Heterorhabditis spp.). In contrast, few soil samples (two samples from Maha Sarakham province and one sample from Nong Khai province) were positive with both Steinernema and Heterorhabditis. Most of the EPNs were isolated from loam, and the mean pH, temperature, and moisture of the soil samples were 6.6, 28.4°C, and 1.5%, respectively (Table 2). These soil parameters were not significantly different between soil samples with and without EPNs (Mann-Whitney test).

Table 1. Number of symbiotic bacteria isolated from soil samples from the Northeastern region of Thailand.

| Province | No. of soil sites | No. of sampling sites with EPNs (%) | No. of soil samples | No. of soil samples with EPNs (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenorhabdus | Photorhabdus | Total | Xenorhabdus | Photorhabdus | Total | |||

| Kalasin | 24 | 6 | 3 | 9 (37.50%) | 120 | 9 | 3 | 12 (10.00%) |

| Khon Kaen | 29 | 5 | 5 | 10 (34.48%) | 145 | 5 | 6 | 11 (7.58%) |

| Chaiyaphum | 60 | 9 | 8 | 17 (28.33%) | 300 | 11 | 11 | 22 (7.33%) |

| Nakhon Ratchasima | 66 | 11 | 12 | 23 (34.85%) | 330 | 17 | 14 | 31 (9.39%) |

| Maha Sarakham | 26 | 3 | 6 | 9 (34.62%) | 130 | 4 | 7 | 11 (8.46%) |

| Loei | 22 | 2 | 0 | 2 (9.09%) | 110 | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.82%) |

| Nong Khai | 20 | 2 | 2 | 4 (20.00%) | 100 | 3 | 2 | 5 (5.00%) |

| Nong Bua Lamphu | 22 | 7 | 5 | 12 (54.55%) | 110 | 7 | 5 | 12 (10.91%) |

| Udon Thani | 20 | 3 | 3 | 6 (30.00%) | 100 | 4 | 3 | 7 (7.00%) |

| Total | 289 | 48 (16.60%) | 44 (15.22%) | 92 (31.82%) | 1,445 | 62 (4.29%) | 51 (3.53%) | 113 (7.82%) |

Table 2. pH, temperature, and moisture content of the soil samples (n = 1,445) in the presence and absence of EPNs.

| Soil parameter | Soil with EPNs | Soil without EPNs | P-value (Mann-Whitney test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 113) | (n = 1,332) | ||||

| Range | Mean | Range | Mean | ||

| pH | 5.2–7.0 | 6.6 | 3.4–7.5 | 6.6 | 0.2144 |

| Temperature (°C) | 25–34 | 28.4 | 22–39 | 28.6 | 0.8401 |

| Moisture (%) | 0.0–8.0% | 1.5% | 0.0–8.0% | 1.7% | 0.7039 |

Identification and phylogenetic tree of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates

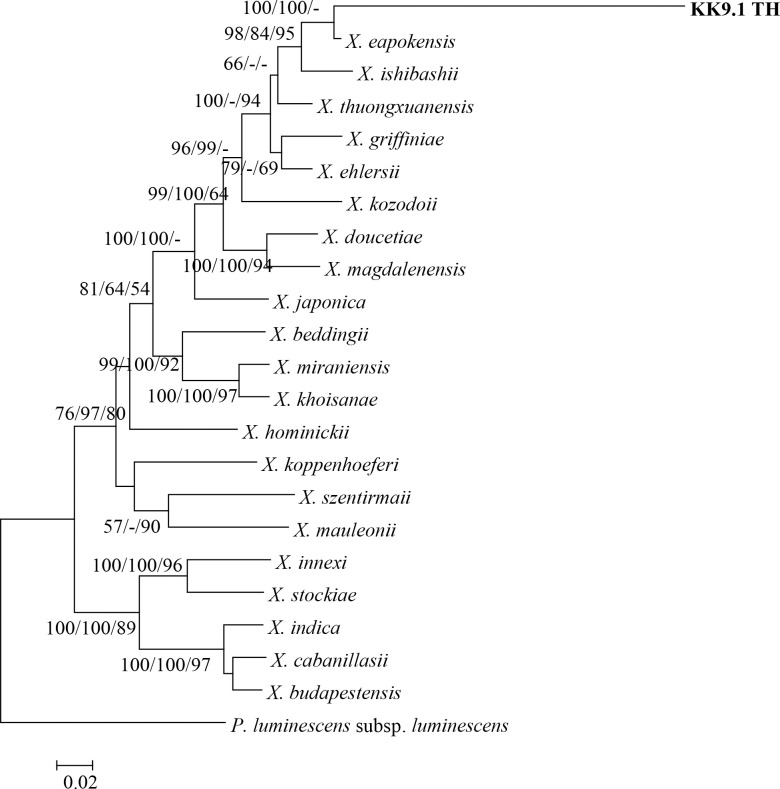

Sixty-two isolates belonging to the genus Xenorhabdus were identified using BLASTN search of partial sequence of the recA gene. Most Xenorhabdus isolates (n = 60) were identified as X. stockiae (97–100% identity). One isolate (bKK26.2_TH) was identified as X. indica (97% identity), but the remaining one isolate (bKK9.1_TH) was unidentified due to low similarity of its recA sequence to that of X. thuongxuanensis (95% identity) and X. eapokensis (94% identity). To confirm the species of Xenorhabdus bKK9.1_TH, five additional genes (16S rDNA, gyrB, dnaN, gltX, and infB) were amplified and sequenced. Nucleotide sequences of four genes revealed high similarity to that of X. eapokensis: 16S rDNA and infB (99% identity), dnaN and gltX (98% identity). gyrB sequence of Xenorhabdus bKK9.1_TH showed low similarity with that of X. eapokensis (90%).

The ML tree derived from all the sequences of recA among the Thai Xenorhabdus isolates and reference strains from GenBank database is shown in Fig 1. The Thai Xenorhabdus isolates were distributed in three groups. Group 1 was the majority group (60 isolates), which was closely related to X. stockiae. Group 2 contained one isolate (bKK26.2_TH), which was closely related to X. indica. Group 3 also contained one isolate (bKK9.1_TH), which fell in the clade of X. thuongxuanensis, X. ishibashii, and X. eapokensis. The ML tree derived from 16S rRNA, gyrB, dnaN, gltX, and infB genes are shown in S1–S5 Figs. The ML tree of concatenation of the five truncated genes (recA, gyrB, dnaN, gltX, and infB) is shown in Fig 2. All phylogenetic trees supported that Xenorhabdus bKK9.1_TH was closely related to X. eapokensis.

Fig 1. Maximum likelihood tree of 62 Xenorhabdus isolates (black bold letter) based on recA gene (588 bp) compared with Xenorhabdus strains downloaded from GenBank.

Escherichia coli was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence. The EPN species from which they were isolated are also shown.

Fig 2. Maximum likelihood tree of concatenated sequences of Xenorhabdus sp. (KK9.1_TH) (shown in bold letter) based on truncated recA (588 bp), gyrB (846 bp), dnaN (828 bp), gltX (1,057 bp), and infB (1,052 bp) compared with the sequences of Xenorhabdus strains from GenBank.

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens is included as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

Fifty-one isolates of Photorhabdus were identified using BLASTN search of partial sequences of the recA gene. Twenty-nine isolates were identified as P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii (97–100% identity) and 18 isolates were identified as P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis (98–100% identity). Two isolates were identified as P. asymbiotica subsp. australis (99–100% identity). The remaining two Photorhabdus isolates were identified as P. luminescens subsp. laumondii (98% identity). ML analysis of 51 recA sequences of Photorhabdus distributed the isolates in three groups. Group 1 contained 47 isolates closely related to P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii and P. luminescens subsp. Group 2 contained two Photorhabdus isolates, which were closely related to P. luminescens subsp. laumondii. Group 3 contained the remaining two isolates of Photorhabdus, which were most closely related to P. asymbiotica subsp. australis (Fig 3).

Fig 3. Maximum likelihood tree of 51 Photorhabdus isolates (black bold letter) based on the 588 bp region of recA gene compared with that of the Photorhabdus strains from GenBank.

Escherichia coli was included as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence. The EPN species from which they were isolated are also shown.

Identification and phylogenetic tree of entomopathogenic nematodes

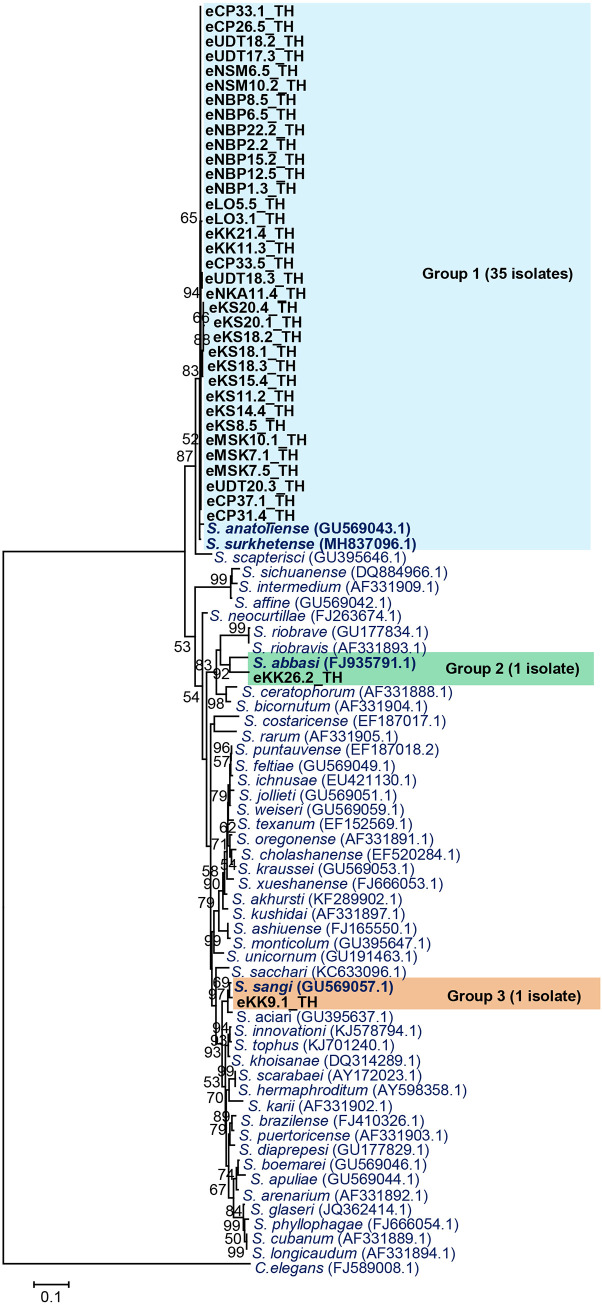

A total of 113 EPNs were isolated from the soil samples. EPNs (80 isolates) were identified using BLASTN search of a partial sequence of 28S rDNA for Steinernema and internal transcribed spacer for Heterorhabditis. The remaining 33 isolates of EPNs were lost due fungal contamination. Thirty-seven isolates were identified as Steinernema and the remaining 43 isolates were identified as Heterorhabditis. Steinernema (35 isolates) were identified as S. surkhetense (97–99% identity). One isolate was identified as S. sangi with 98% similarity. Species of the remaining one isolate Steinernema eKK26.2_TH was unidentified due to its low identity with S. abbasi (90%).

The phylogenetic relationships among the Steinernema isolates and reference strains from GenBank database are shown in Fig 4. The ML analysis of the 37 sequences distributed them into three groups. Group 1 contained 35 isolates of Steinernema, which were closely related to S. surkhetense and S. anatoliense. Group 2 contained only one isolate, which was closely related to S. abbasi. Group 3 contained one isolate of Steinernema, which was closely related to S. sangi.

Fig 4. Maximum likelihood tree of 37 Steinernema isolates (black bold letter) based on the partial sequence of 28S rDNA (623–630 bp) compared with Steinernema reference strains from NCBI.

Caenorhabditis elegans was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. Numbers shown above the branches are bootstrap percentages for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 10% sequence divergence.

For Heterorhabditis nematodes, 39 isolates were identified as H. indica (98–100% identity), one isolate was identified as H. baujardi (99% identity), and three isolates were identified as Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3 (97–99% identity). ML analysis of the 43 sequences of Heterorhabditis distributed them into three groups (Fig 5). Group 1 was the majority group (39 isolates), which was closely related to the clade of H. indica. Group 2 contained only one isolate, which was closely related to H. baujardi. Group 3 contained three isolates, which were closely related to Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3.

Fig 5. Maximum likelihood tree of 43 Heterorhabditis isolates (black bold letter) based on the partial sequence of internal transcribed spacer (495–548 bp) compared with Heterorhabditis reference strains from NCBI.

Caenorhabditis elegans was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. Numbers shown above the branches are bootstrap percentages for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence.

Maximum association was observed between X. stockiae and the nematode host S. surkhetense (35 isolates). A single isolate of X. indica was associated with Steinernema sp., and one isolate of Xenorhabdus sp. (bKK9.1_TH), closely related to X. eapokensis, was associated with S. sangi. In addition, 39 isolates of P. luminescens were associated with H. indica. A single isolate of P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii was associated with H. baujardi. Two isolates of P. asymbiotica subsp. australis were associated with H. indica. A single isolate of P. luminescens subsp. luamondii was associated with Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3.

Antibacterial activity

We found that whole cell extracts of four (X. stockiae, n = 3 and X. indica, n = 1) out of 113 isolates could inhibit the growth of at least one antibiotic-resistant bacterial strain. The extract from these bacterial isolates was tested against the antibiotic-resistant bacteria by disk diffusion method. Two isolates of X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH and bKS8.5_TH) and one isolate of X. indica (bKK26.2_TH) showed potential inhibition of the growth of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Table 3). X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) could inhibit A. baumannii strain AB320 (extensively drug resistant; XDR), A. baumannii strain AB321, AB322 (multi drug resistant; MDR), A. baumannii strain AB324 (XDR), S. aureus ATCC20475, S. aureus strain PB36 (methicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA), E. coli ATCC35218, E. coli strain PB1 (extended spectrum beta-lactamase; ESBL and MDR), E. coli strain PB231 (ESBL and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; CRE), P. aeruginosa strain PB30 (MDR), K. pneumoniae ATCC700603, K. pneumoniae strain PB5 (ESBL and MDR), and K. pneumoniae strain PB21 (ESBL and CRE). X. stockiae (bKS8.5_TH) and X. indica (bKK26.2_TH) could inhibit S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA). However, X. stockiae (bUDT18.2_TH) was unable to inhibit any antibiotic-resistant bacteria by the disk diffusion method.

Table 3. Antibacterial activity of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus extracts against antibiotic-resistant bacteria as assessed by disk diffusion.

| Bacteria (code) | Inhibit the growth of drug resistant bacteria | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii strain AB320 (XDR) a | A. baumannii strain AB321 (MDR) b | A. baumannii strain AB322 (MDR) b | A. baumannii strain AB324 (XDR) a | S. aureus ATCC20475 | S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA)c | S. aureus strain PB57 (MRSA)c | E. coli ATCC35218 | E. coli strain PB1 (ESBL and MDR)d,b | E. coli strain PB231 (ESBL and CRE) d,e | P. aeruginosa strain PB30 (MDR)b | E. faecalis ATCC51299 | K.pneumoniaeATCC700603 | K. pneumoniae strain PB5 (ESBL and MDR) d,b | K. pneumoniae strain PB21 (ESBL and CRE) d,e | |

| X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| X. stockiae (bKS8.5_TH) | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X. stockiae (bUDT18.2_TH) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X. indica (bKK26.2_TH) | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

- No activity (6 mm), + weak inhibition (7–10 mm.), ++ moderate/average inhibition (11–15 mm.)

aextensively drug resistant

bmultidrug resistant

cmethicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus, and

dextended spectrum beta-lactamase, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

We also evaluated the MIC and MBC of X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) extract against 13 antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, including A. baumannii strain AB320 (XDR), A. baumannii strain AB321, AB322 (MDR), A. baumannii strain AB324 (XDR), S. aureus ATCC20475, S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA), E. coli ATCC35218, E. coli strain PB1 (ESBL and MDR), E. coli strain PB231 (ESBL and CRE), P. aeruginosa strain PB30 (MDR), K. pneumoniae ATCC700603, K. pneumoniae strain PB5 (ESBL and MDR), and K. pneumoniae strain PB21 (ESBL and CRE). MIC and MBC of X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) extract against these antibiotic-resistant bacteria were 3.90 mg/mL and 7.81 mg/mL, respectively, whereas X. stockiae (bKS8.5_TH) and X. indica (bKK26.2 TH) showed potential efficacy only against S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA). MIC and MBC of X. stockiae (bKS8.5_TH) and X. indica (bKK26.2_TH) extracts against S. aureus strain PB36 were 62.5 mg/mL and 15.62 mg/mL, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4. Antibacterial activity of Xenorhabdus extracts against antibiotic-resistant bacteria as assessed by minimum inhibitory concentration and minimal bactericidal concentration.

| Bacterial list (Code) | Concentration of inhibition (mg/mL) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA) | K. pneumoniae strain PB5 (ESBL+MDR) | A. baumannii strain AB320 (XDR) | P. aeruginosa strain PB30 (MDR) | E. coli strain PB1 (ESBL+MDR) | ||||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) | 3.9 | 7.81 | 3.9 | 7.81 | 3.9 | 7.81 | 3.9 | 7.81 | 3.9 | 7.81 |

| X. stockiae (bKS8.5_TH) | 62.5 | 62.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X. indica (bKK26.2_TH) | 15.62 | 15.62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Discussion

The overall recovery rate of the EPNs (Steinernema and Heterorhabditis) from soil samples of Northeastern region of Thailand was 7.82%. This result was similar to that reported by Brodie [31] from Fiji Islands (7.3%), Valadas [32] from Portugal (6.7%), and Hatting [33] from South Africa (5%). However, this rate was higher than those reported by Caoili [34] from the Philippines (2.5%), Majić [35] from Croatia (2.0%), and Noujeim [36] from Lebanon (1%). Higher prevalence of EPNs in soil from that determined in the present study was observed by Kanga [37] from Southern Cameroon (10.4%), Khatri-Chhetri [38] in Nepal (10.5%), and Malan [39] in South Africa (17%). This suggests that global prevalence of EPNs is variable. Distribution of Steinernema and Heterorhabditis has been reported from several ecological niches in USA, Australia, Europe, and Asia, including Thailand [8, 15–18, 24, 40, 41]. Biotic and abiotic characteristics influence the distribution of the EPNs; however, in our study, soil temperature, moisture, and pH of the soil samples with and without EPNs were not significantly different. Nevertheless, our data supported previous reports from Thailand, which showed that EPNs were able to survive in a diverse soil environment and various soil types with a wide range of pH (3.2–6.9), temperature (20°C-32°C), and moisture (0–8%) [17, 18, 22, 23]. Soil moisture, temperature, and rainfall affect the distribution of the insects that could be probable hosts for the EPNs [42]. This could also affect the distribution of EPNs.

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of 62 Xenorhabdus isolates revealed that X. stockiae was the predominant species. This bacterium was hosted by S. surkhetense, which has been previously described from India [43]. X. stockiae has also been isolated from S. siamkayai and S. minutum in Thailand [16, 24, 44, 45]. It was reported as a bacterial symbiont with S. huense in Vietnam [46]. One isolate of X. indica was found to be associated with Steinernema sp. (90% similar with S. abbasi). X. indica was first reported to be associated with S. thermophilum [47]. Subsequently, the association between X. indica and S. abbasi was reported from Taiwan [48]. In a previous study, X. indica was associated with S. yirgalemense [49], and in the current study, it was found that X. indica, an Indian isolate, was associated with S. pakistanense [50]. This suggests that X. indica may be symbiotically associated with a wide range of EPN hosts.

A single isolate of Xenorhabdus (bKK9.1_TH) showed low similarity with X. thuongxuanensis (95% identity) and X. eapokensis (95% identity) by recA sequence analysis. In contrast, higher similarity of this isolate was found with X. eapokensis when 16S rDNA and infB (99% identity), and gltX and dnaN (98% identity) sequences were analyzed. In addition, multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) based on concatenated partial gene sequences of recA, gyrB, dnaN, gltX, and infB revealed that Xenorhabdus (bKK9.1_TH) was closely related to X. eapokensis. Therefore, we identified Xenorhabdus (bKK9.1_TH) as X. eapokensis. This suggests that analysis of multiple genes may aid in the identification of this bacterium. Also, whole genome sequencing of this bacterium may assist in confirmation of its identity at the species level. We found that X. eapokensis was associated with S. sangi, which has been reported as a host for X. vietnamensis and X. thuongxuanensis [25, 51].

For the genus Photorhabdus, in the current study, the following four species were identified: P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii (n = 29), P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis (18 isolates), P. luminescens subsp. luamondii (n = 2), and P. asymbiotica subsp. australis (n = 2). P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii and P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis were associated with H. indica and H. sp. SGmg3. These associations have been previously reported from Thailand [15, 17, 18]. In addition, P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis has also been isolated from H. baujardi in Thailand [8]; however, P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii has been found in association with H. bacteriophora in Iran, Hungary, Argentina, USA, and in association with H. indica in China [19]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on mutualistic association between P. luminescens subsp. luamondii and Heterorhabditis sp. SGmg3. However, P. luminescens subsp. luamondii has also been reported to be associated with H. bacteriophora in Thailand, USA, and Argentina [17, 52] and with H. safricana from South Africa [53]. P. asymbiotica subsp. australis was also found in the present study, which was in association with H. indica. This association has been found in Thailand previously [17, 54]. P. asymbiotica is an emerging pathogen that has been reported to cause locally invasive soft tissue infection and disseminated bacteremia; clinical cases have been identified in both Australia and USA [55, 56]. This suggests that P. asymbiotica could also cause these diseases in the residents of Thailand. Although no clinical case of P. asymbiotica infection has been reported in the country, management and healthcare strategies should be prepared in advance.

In the current study, X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) extract showed the highest inhibitory effect against several antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Previous studies have shown that Xenorhabdus produces xenocoumacin [57] and amicoumacin derivatives [58], which are potent against S. aureus [59]. All Photorhabdus extracts from Mae Wong national park could inhibit S. aureus ATCC20475, S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA), and S. aureus strain PB57 (MRSA) (8). In addition, P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii (bSBR11.1_TH) extract from Saraburi province could inhibit up to 10 antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains, and all Photorhabdus isolates showed the potential to inhibit the growth of S. aureus strain PB36 (MRSA) [41]. P. luminescens has been reported to produce isopropylstilbene [44, 60], which has multiple biological activities, including antibiotic activity against E. coli, B. subtilis, S. pyogenes, and S. aureus RN4220 (drug resistant and clinical isolate) [61, 62]. The bio-activity of isopropylstilbene has been extended to inhibit the growth of fungi [10]. We found that the bioactivity (MIC and MBC) of the crude extracts emphasized that the X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) extracts were active against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The MIC values exhibited by all the extracts in this study ranged between 3.90–62.5 mg/mL, and the MBC ranged between 7.81–15.62 mg/ml. This may be due to the ability of each symbiotic bacterial isolate to produce different effective metabolites to kill drug resistant bacteria. This suggests that Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates are potential agents for the inhibition of the growth of MDR bacteria. Therefore, both Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolates are a potential source for novel antibiotics.

Conclusions

In summary, 113 isolates of EPNs were obtained from a total of 1,445 soil samples collected from 289 sites in Northeastern region of Thailand. S. surkhetense and H. indica were the two most common EPN species found in the soil samples. For symbiotic bacteria, X. stockiae, X. indica, X. eapokensis, P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii, P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis, and P. asymbiotica subsp. australis were found in the studied area, and X. stockiae and P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii were found to be predominant. The common associations observed between EPN hosts and their symbiotic bacteria were S. surkhetense-X. stockiae and H. indica-P. luminescens. EPN host of X. eapokensis was S. sangi and that of X. indica was unidentified Steinernema. In addition, the crude extract from X. stockiae (bMSK7.5_TH) showed a broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against several antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains. Thus, this study will be useful in further drug discovery from natural resources.

Supporting information

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Miss Nongluk Loetjaratkuntaworn and Miss Kanittha Phumdoung for their assistance in soil collection. We are grateful to Professor Gavin P. Reynolds, Faculty of Medical Science, Naresuan University for English language editing.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Center of Excellence on Biodiversity (BDC), Office of Higher Education Commission (BDC-PG4-161011). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Akhurst RJ. Neoaplectana species: specificity of association with bacteria of the genus Xenorhabdus. Exp Parasitol. 1983;55(2):258–63. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(83)90020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poinar GO Jr, Thomas GM. Significance of Achromobacter nematophilus Poinar and Thomas (Achromobacteraceae: Eubacteriales) in the development of the nematode, DD-136 (Neoaplectana sp. Steinernematidae). Parasitology. 1966;56(2):385–90. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000070980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis EE, Clarke DJ. Nematode parasites and entomopathogens. In: Vega FE, Kaya HK, editors. Insect Pathology. 2nd ed: Elsevier; 2012. p. 395–424. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu D, Macchietto M, Chang D, Barros MM, Baldwin J, Mortazavi A, et al. Activated entomopathogenic nematode infective juveniles release lethal venom proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(4):e1006302. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang DZ, Serra L, Lu D, Mortazavi A, Dillman AR. A core set of venom proteins is released by entomopathogenic nematodes in the genus Steinernema. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(5):e1007626. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eleftherianos I, Boundy S, Joyce SA, Aslam S, Marshall JW, Cox RJ, et al. An antibiotic produced by an insect-pathogenic bacterium suppresses host defenses through phenoloxidase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(7):2419–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610525104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McInerney BV, Taylor WC, Lacey MJ, Akhurst RJ, Gregson RP. Biologically active metabolites from Xenorhabdus spp., Part 2. Benzopyran-1-one derivatives with gastroprotective activity. J Nat Prod. 1991;54(3):785–95. doi: 10.1021/np50075a006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muangpat P, Yooyangket T, Fukruksa C, Suwannaroj M, Yimthin T, Sitthisak S, et al. Screening of the Antimicrobial Activity against Drug Resistant Bacteria of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus Associated with Entomopathogenic Nematodes from Mae Wong National Park, Thailand. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1142. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhurst RJ. Antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with insect pathogenic nematodes of the families Heterorhabditidae and Steinernematidae. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128(12):3061–5. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-12-3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G. Antimicrobial Activity of the Nematode Symbionts, Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus (Enterobacteriaceae), and the Discovery of Two Groups of Antimicrobial Substances, Nematophin and Xenorxides. In: Canada (Doctoral dissertation). British Columbia: Simon Fraser University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundmann F, Kaiser M, Schiell M, Batzer A, Kurz M, Thanwisai A, et al. Antiparasitic chaiyaphumines from entomopathogenic Xenorhabdus sp. PB61.4. J Nat Prod. 2014;77(4):779–83. doi: 10.1021/np4007525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the Internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997Apr;47(2):590–2. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [cited 2021 July 23]. Available from: http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt DJ. Introduction. In: Hunt DJ, Nguyen KB, editors. Advances in entomopathogenic nematode taxonomy and phylogeny. Nematology Monographs and Perspectives 12: Brill; 2016. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hominick WM. Biogeography. In: Gaugler R, editor. Entomopathogenic nematology. CABI Publishing; 2002. p. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukruksa C, Yimthin T, Suwannaroj M, Muangpat P, Tandhavanant S, Thanwisai A, et al. Isolation and identification of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus bacteria associated with entomopathogenic nematodes and their larvicidal activity against Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10(1):440. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2383-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tailliez P, Pages S, Ginibre N, Boemare N. New insight into diversity in the genus Xenorhabdus, including the description of ten novel species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006; 56: 2805–2818. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64287-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thanwisai A, Tandhavanant S, Saiprom N, Waterfield NR, Long PK, Bode HB, et al. Diversity of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp. and Their Symbiotic Entomopathogenic Nematodes from Thailand. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7: e43835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yooyangket T, Muangpat P, Polseela R, Tandhavanant S, Thanwisai A, Vitta A. Identification of entomopathogenic nematodes and symbiotic bacteria from Nam Nao National Park in Thailand and larvicidal activity of symbiotic bacteria against Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maneesakorn P, An R, Daneshvar H, Taylor K, Bai X, Adams BJ, et al. Phylogenetic and cophylogenetic relationships of entomopathogenic nematodes (Heterorhabditis: Rhabditida) and their symbiotic bacteria (Photorhabdus: Enterobacteriaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;59(2):271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt DJ, Subbotin SA. Taxonomy and Systematics. In: Hunt DJ, Nguyen KB, editors. Advances in entomopathogenic nematode taxonomy and phylogeny. Nematology Monographs and Perspectives 12: Brill; 2016. p. 13–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stock SP, Somsook V, Reid AP. Steinernema siamkayai n. sp. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae), an entomopathogenic nematode from Thailand. Systematic Parasitology. 1998;41(2):105–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1006087017195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitta A, Fukruksa C, Yimthin T, Deelue K, Sarai C, Polseela R, et al. Preliminary Survey of Entomopathogenic Nematodes in Upper Northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2017;48(1):18–26. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White GF. A Method for Obtaining Infective Nematode Larvae from Cultures. Science. 1927;66(1709):302–3. doi: 10.1126/science.66.1709.302-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tailliez P, Laroui C, Ginibre N, Paule A, Pages S, Boemare N. Phylogeny of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus based on universally conserved protein-coding sequences and implications for the taxonomy of these two genera. Proposal of new taxa: X. vietnamensis sp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. caribbeanensis subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. hainanensis subsp. nov., P. temperata subsp. khanii subsp. nov., P. temperata subsp. tasmaniensis subsp. nov., and the reclassification of P. luminescens subsp. thracensis as P. temperata subsp. thracensis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60: 1921–37. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.014308-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kampfer P, Tobias NJ, Ke LP, Bode HB, Glaeser SP. Xenorhabdus thuongxuanensis sp. nov. and Xenorhabdus eapokensis sp. nov., isolated from Steinernema species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67(5):1107–14. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–42. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seier-Petersen MA, Jasni A, Aarestrup FM, Vigre H, Mullany P, Roberts AP, et al. Effect of subinhibitory concentrations of four commonly used biocides on the conjugative transfer of Tn916 in Bacillus subtilis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(2):343–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yimthin T, Fukruksa, C, Loetjaratkuntaworn, N, Phumdoung K, Vitta A, Thanwisai A. Identification of Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. isolated from Entomopathogenic nematodes of Kalasin province, Thailand. M. Sc. Thesis, Naresuan University. 2014.

- 31.Brodie G. Natural occurrence and distribution of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae, Heterorhabditidae) in Viti Levu, Fiji Islands. J Nematol. 2020;52:1–17. doi: 10.21307/jofnem-2020-017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valadas V, Laranjo M, Mota M, Oliveira S. A survey of entomopathogenic nematode species in continental Portugal. J Helminthol. 2014;88(3):327–41. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X13000217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatting J, Patricia Stock S, Hazir S. Diversity and distribution of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae, Heterorhabditidae) in South Africa. J Invertebr Pathol. 2009;102(2):120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caoili BL, Latina RA, Sandoval RFC, Orajay JI. Molecular Identification of Entomopathogenic Nematode Isolates from the Philippines and their Biological Control Potential Against Lepidopteran Pests of Corn. J Nematol. 2018;50(2):99–110. doi: 10.21307/jofnem-2018-024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majic I, Sarajlic A, Lakatos T, Toth T, Raspudic E, Zebec V, et al. First Report of Entomopathogenic Nematode Steinernema Feltiae (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) from Croatia. Helminthologia. 2018;55(3):256–60. doi: 10.2478/helm-2018-0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noujeim E, Khater C, Pages S, Ogier JC, Tailliez P, Hamze M, et al. The first record of entomopathogenic nematodes (Rhabiditiae: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) in natural ecosystems in Lebanon: A biogeographic approach in the Mediterranean region. J Invertebr Pathol. 2011;107(1):82–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanga FN, Waeyenberge L, Hauser S, Moens M. Distribution of entomopathogenic nematodes in Southern Cameroon. J Invertebr Pathol. 2012;109(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khatri-Chhetri HB, Waeyenberge L, Manandhar HK, Moens M. Natural occurrence and distribution of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) in Nepal. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103(1):74–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malan AP, Knoetze R, Moore SD. Isolation and identification of entomopathogenic nematodes from citrus orchards in South Africa and their biocontrol potential against false codling moth. J Invertebr Pathol. 2011;108(2):115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hominick WM, Reid AP, Bohan DA, Briscoe BR. Entomopathogenic Nematodes: Biodiversity, Geographical Distribution and the Convention on Biological Diversity. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 1996;6(3):317–32. doi: 10.1080/09583159631307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muangpat P, Suwannaroj M, Yimthin T, Fukruksa C, Sitthisak S, Chantratita N, et al. Antibacterial activity of Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus isolated from entomopathogenic nematodes against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia del Pino F, Palomo A. Natural Occurrence of Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae) in Spanish Soils. J Invertebr Pathol. 1996;68(1):84–90. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1996.0062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhat AH, Istkhar, Chaubey AK, Puza V, San-Blas E. First Report and Comparative Study of Steinernema surkhetense (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) and its Symbiont Bacteria from Subcontinental India. J Nematol. 2017;49(1):92–102. doi: 10.21307/jofnem-2017-049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buscato E, Buttner D, Bruggerhoff A, Klingler FM, Weber J, Scholz B, et al. From a multipotent stilbene to soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors with antiproliferative properties. ChemMedChem. 2013;8(6):919–23. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maneesakorn P, Grewal PS, Chandrapatya A. Steinernema minutum sp. nov. (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae): a new entomopathogenic nematode from Thailand. International Journal of Nematology. 2010;20(1):27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phan KL, Mráček Z, Půža V, Nermut J, Jarošová A. Steinernema huense sp. n., a new entomopathogenic nematode (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) from Vietnam. J Nematol. 2014; 16: 761–775. doi: 10.1163/15685411-00002806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Somvanshi VS, Lang E, Ganguly S, Swiderski J, Saxena AK, Stackebrandt E. A novel species of Xenorhabdus, family Enterobacteriaceae: Xenorhabdus indica sp. nov., symbiotically associated with entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema thermophilum Ganguly and Singh, 2000. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2006;29(7):519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai MH, Tang LC, Hou RF. The bacterium associated with the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema abbasi (Nematoda: Steinernematidae) isolated from Taiwan. J Invertebr Pathol. 2008;99(2):242–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferreira T, van Reenen CA, Tailliez P, Pages S, Malan AP, Dicks LM. First report of the symbiotic bacterium Xenorhabdus indica associated with the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema yirgalemense. J Helminthol. 2016;90(1):108–12. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X14000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhat AH, Askary TH, Ahmad MJ, Suman, Aasha, Chaubey AK. Description of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora (Nematoda: Heterorhabditidae) isolated from hilly areas of Kashmir Valley. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control volume. 2019;29(1). doi: 10.1186/s41938-019-0197-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lalramnghaki HC, Vanlalhlimpuia, Vanramliana, Lalramliana. Characterization of a new isolate of entomopathogenic nematode, Steinernema sangi (Rhabditida, Steinernematidae), and its symbiotic bacteria Xenorhabdus vietnamensis (gamma-Proteobacteria) from Mizoram, northeastern India. J Parasit Dis. 2017;41(4):1123–31. doi: 10.1007/s12639-017-0945-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fischer-Le Saux M, Viallard V, Brunel B, Normand P, Boemare NE. Polyphasic classification of the genus Photorhabdus and proposal of new taxa: P. luminescens subsp. luminescens subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. akhurstii subsp. nov., P. luminescens subsp. laumondii subsp. nov., P. temperata sp. nov., P. temperata subsp. temperata subsp. nov. and P. asymbiotica sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49Pt 4:1645–56. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geldenhuys J, Malan AP, Dicks LM. First Report of the Isolation of the Symbiotic Bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens subsp. laumondii Associated with Heterorhabditis safricana from South Africa. Curr Microbiol. 2016;73(6):790–5. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suwannaroj M, Yimthin T, Fukruksa C, Muangpat P, Yooyangket T, Tandhavanant S, et al. Survey of entomopathogenic nematodes and associate bacteria in Thailand and their potential to control Aedes aegypti. J. appl. Entomol. 2020;144(3):212–23. doi: 10.1111/jen.12726 29641570 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerrard JG, Joyce SA, Clarke DJ, ffrench-Constant RH, Nimmo GR, Looke DF, et al. Nematode symbiont for Photorhabdus asymbiotica. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(10):1562–4. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weissfeld AS, Halliday RJ, Simmons DE, Trevino EA, Vance PH, O’Hara CM, et al. Photorhabdus asymbiotica, a pathogen emerging on two continents that proves that there is no substitute for a well-trained clinical microbiologist. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4152–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4152-4155.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reimer D, Luxenburger E, Brachmann AO, Bode HB. A new type of pyrrolidine biosynthesis is involved in the late steps of xenocoumacin production in Xenorhabdus nematophila. Chembiochem. 2009;10(12):1997–2001. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park HB, Perez CE, Perry EK, Crawford JM. Activating and Attenuating the Amicoumacin Antibiotics. Molecules. 2016;21(7):824. doi: 10.3390/molecules21070824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bode HB. Entomopathogenic bacteria as a source of secondary metabolites. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13(2):224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Chen G, Wu H, Webster JM. Identification of two pigments and a hydroxystilbene antibiotic from Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(12):4329–33. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4329-4333.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Derzelle S, Duchaud E, Kunst F, Danchin A, Bertin P. Identification, characterization, and regulation of a cluster of genes involved in carbapenem biosynthesis in Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(8):3780–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.3780-3789.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi D, An R, Zhang W, Zhang G, Yu Z. Stilbene Derivatives from Photorhabdus temperata SN259 and Their Antifungal Activities against Phytopathogenic Fungi. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(1):60–5. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 5% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

P. luminescens subsp. luminescens was used as an out-group. Bootstrap values are reported out of 1000 replicates. The numbers shown above the branches are support values of Maximum likelihood/Neighbor-joining/Bayesian posterior probabilities for clades supported above the 50% level. The bar indicates 2% sequence divergence.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.