Abstract

Introduction

Prior work suggests that the prevalence of cigarette smoking is persistently higher among people with mental health problems, relative to those without. Lower quit rates are one factor that could contribute to higher prevalence of smoking in this group. This study estimated trends in the cigarette quit rates among people with and without past-month serious psychological distress (SPD) from 2008 to 2016 in the United States.

Methods

Data were drawn from 91 739 adult participants in the 2008–2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a repeated, cross-sectional, national survey. Linear time trends of cigarette quit rates, stratified by past-month SPD, were assessed using logistic regression models with continuous year as the predictor.

Results

Cigarette quit rates among individuals with past-month SPD were lower than among those without SPD every year from 2008 to 2016. Quit rates did not change appreciably among those with past-month SPD (odds ratio = 1.02 [0.99, 1.06]) from 2008 to 2016, whereas quit rates increased among those without past-month SPD (odds ratio = 1.02 [1.01, 1.02]).

Conclusions

In the United States, quit rates among individuals with past-month SPD are approximately half than quit rates of those without SPD and have not increased over the past decade. This discrepancy in quit rates may be one factor driving increasing disparities in prevalence of smoking among those with versus without mental health problems. Tobacco control efforts require effective and targeted interventions for those with mental health problems.

Implications

Cigarette smoking quit rates have not increased among persons with serious mental health problems over the past decade. This work extends prior findings showing that smoking prevalence is not declining as quickly among persons with serious mental health problems. Findings suggest that diverging trends in quit rates are one possible driver of the persistent disparity in smoking by mental health status. Innovation in both tobacco control and targeted interventions for smokers with mental health problems is urgently needed.

Introduction

Individuals with mental health problems have been classified as a tobacco use disparity group and experience disproportionate consequences of cigarette smoking.1 Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking has decreased in the United States,2 the prevalence of smoking among those with serious psychological distress (SPD) has remained relatively stable.3 SPD refers to mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate-to-serious impairment across several domains and warrant treatment.4 Current smoking, higher daily cigarette consumption, and nicotine dependence are more common among individuals with SPD relative to those without SPD in the United States5–8 and other developed countries (eg, Australia and the United Kingdom).9,10

Prevalence of a disease or condition in a population is determined by incidence combined with duration of the condition. Therefore, we can understand the prevalence of smoking to be driven by both smoking initiation and quit rate. Thus, a lower quit rate leads to more time in the “smoking” population, and therefore sustained prevalence. Prior studies suggest that the cigarette initiation rate is higher among persons with mood disorders and schizophrenia compared to individuals without.11 Although increases in quit attempts among persons with and without SPD from 1997 to 2015 appear similar,5 several cross-sectional, US nationally representative studies have found that those with SPD are less likely to successfully quit smoking.6–8 Limitations of these studies include the use of older data (from ≥10 years ago) and broad measures of SPD rather than assessing recent or acute SPD.

To the best of our knowledge, prior studies have not examined recent trends in cigarette smoking quit rates over time by SPD status using recent nationally representative US data with a measure of acute SPD (ie, past month). Acute distress is often thought to precipitate cigarette use. Knowledge of trends in quitting behavior among those with acute SPD can provide new insights into whether differential quit rates by SPD status may be contributing to sustained prevalence or potentially slowed decline in smoking among those with SPD. Against this background, this study’s aims are threefold: (1) to estimate cigarette smoking quit rates among those with and without past-month SPD in 2016, (2) to estimate quit rates from 2008 to 2016 by SPD status, and (3) to investigate demographic differences in quit rates over time by SPD status by examining interactions between survey year, SPD status, and demographics.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Data for this study came from The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which collects annual cross-sectional data in multistage representative probability samples of US male and female civilian non-institutionalized persons age 12 years and older in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The current analyses included participants who were 26 years of age or older and who met criteria for lifetime cigarette use from 2008 to 2016 (unweighted n = 91 739). We limited the population to those 26 years of age and older as smoking initiation after age 26 is uncommon.2

The datasets from each year were concatenated, adding a variable for the survey year. Person-level analysis sampling weight for the NSDUH was computed to control for individual-level nonresponse and adjusted to ensure consistency with population estimates obtained from the US Census Bureau. To use the 9 years of combined data, a new weight was created on aggregating the 9 datasets by dividing the original weight by the number of datasets combined. Further descriptions of the NSDUH are found elsewhere.12

Variables and Measurement

Outcome: Cigarette Smoking Quit Rate

Respondents were classified as ever smokers if they reported at least 100 lifetime cigarettes. Respondents were classified as former smokers if they reported at least 100 lifetime cigarettes and no past-year smoking. The quit rate (ie, outcome of interest) was calculated as the proportion of former smokers among ever smokers.

Exposure: Past-month SPD

Nonspecific psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) screening instrument.13 The K6 is a 6-item scale assessing the past-month frequency of feeling nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, sad or depressed, that everything was an effort, down on oneself, no good, or worthless on a 5-point Likert scale (4 = all of the time, 0 = none of the time). Items were summed across the six items and scores of 13 or greater were classified as indicating SPD (ie, the exposure of interest), consistent with other studies..14,15 The K6 has demonstrated strong sensitivity and specificity in detecting DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses.13

Confounding Variables: Demographics

Demographic characteristics (ie, potential confounders) were categorized as follows: age (26–34 years old as reference, 35–49 years old, 50–64 years old, 65 years or older), gender (male as reference group, female), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic [NH] White as reference group, NH Black, Hispanic, NH Other, ie, NH Native American or Alaskan, NH Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, NH Asian, and NH more than one race), and total annual family income (<$20 000 as reference group, $20 000–$49 999, $50 000–$74 999, $75 000 or more).

Statistical Methods

To estimate the quit rate from 2008 to 2016 by past-month SPD status, the proportion of former smokers and associated standard errors among ever smokers stratified by past-month SPD status were calculated for each year. Time trends in quit rate for each SPD status (past-month SPD, no past-month SPD) were tested using logistic regression with continuous year as the predictor for the linear time trend. To determine whether there were differential time trends in quit rate by SPD status, additional logistic regressions were run that included the two-way interaction of year by SPD status. Three-way interactions of year X SPD status X demographics (ie, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and income) were examined using logistic regression for quit rates as sensitivity analyses. However, none of the three-way interactions for any of the demographic characteristics considered (age [F(3,108) = 0.97, p = .409] gender [F(1,110) = 1.84, p = .178], race/ethnicity [F(3,108) = 0.58, p = .639], income [F(3,108) = 1.99, p = .120]) were significant, and thus were not explored further. Analyses were conducted unadjusted and adjusted, accounting for gender, age, income, and race/ethnicity. All analyses were performed incorporating the NSDUH sampling weights and controlling for the complex clustered sampling using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.1 (RTI International; Research Triangle Park, NC; http://www.rti.org/sudaan/) and STATA SE version 15, (StataCorp., 2017) which use the Taylor series estimation methods to provide accurate standard errors.12

Results

Participants

Smoking quit rates by SPD status and demographic characteristics for 2016 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Association Between Cigarette Smoking Quit Rates and Serious Psychological Distress (SPD), by Demographic Characteristics, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2016

| Quit rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SPD | SPD | SPD vs. no SPD | SPD vs. no SPD | |||

| Characteristic | wt% (SE) | wt% (SE) | OR (95% CI) | p int | aORa (95% CI) | p int |

| Total sample | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.3) | 0.29 (0.22 to 0.34) | <.001 | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.63) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.15 to 0.33) | REF | 0.33 (0.20 to 0.55) | REF |

| Female | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.04) | 0.34 (0.24 to 0.50) | .100 | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.77) | .103 |

| Age (y) | ||||||

| 26–34 | 0.28 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.78) | REF | 0.62 (0.41 to 0.94) | REF |

| 35–49 | 0.41 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.03) | 0.38 (0.27 to 0.54) | .154 | 0.46 (0.31 to 0.68) | .196 |

| 50–64 | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.06) | 0.35 (0.19 to 0.65) | .231 | 0.42 (0.23 to 0.76) | .215 |

| 65+ | 0.77 (0.01) | 0.44 (0.12) | 0.23 (0.09 to 0.63) | .123 | 0.28 (0.10 to 0.78) | .135 |

| Annual income | ||||||

| <$20 000 | 0.35 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.19 to 0.58) | REF | 0.39 (0.19 to 0.79) | REF |

| $20 000–$49 999 | 0.47 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.04) | 0.33 (0.21 to 0.51) | .966 | 0.49 (0.30 to 0.78) | .611 |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 0.55 (0.01) | 0.35 (0.10) | 0.43 (0.18 to 1.02) | .587 | 0.48 (0.21 to 1.07) | .513 |

| ≥$75 000 | 0.62 (0.01) | 0.36 (0.06) | 0.35 (0.20 to 0.60) | .907 | 0.42 (0.24 to 0.75) | .822 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 0.55 (0.01) | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.27 (0.21 to 0.36) | REF | 0.46 (0.34 to 0.63) | REF |

| Black | 0.39 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.53) | .512 | 0.28 (0.09 to 0.86) | .471 |

| Hispanic | 0.46 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.12) | 0.55 (0.19 to 1.60) | .187 | 0.47 (0.16 to 1.40) | .737 |

| Other | 0.44 (0.03) | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.19 (0.08 to 0.45) | .463 | 0.29 (0.12 to 0.71) | .349 |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; REF, reference group; SE, standard error; SPD = serious psychological distress; wt%, weighted percentage; y, years.

p int = p value from t test for product term beta = 0; test for multiplicative interaction.

aAdjusted for all other variables listed in the table.

Cigarette Quit Rate Among Persons With and Without SPD, 2016

In 2016, cigarette quit rates were lower among those with past-month SPD compared to those without SPD (24% vs. 52%, p < .001; Table 1). In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the strength of the relationship between quit rate and past-month SPD did not differ among demographic subgroups (Table 1).

Cigarette Quit Rates Among Persons With and Without SPD, 2008–2016

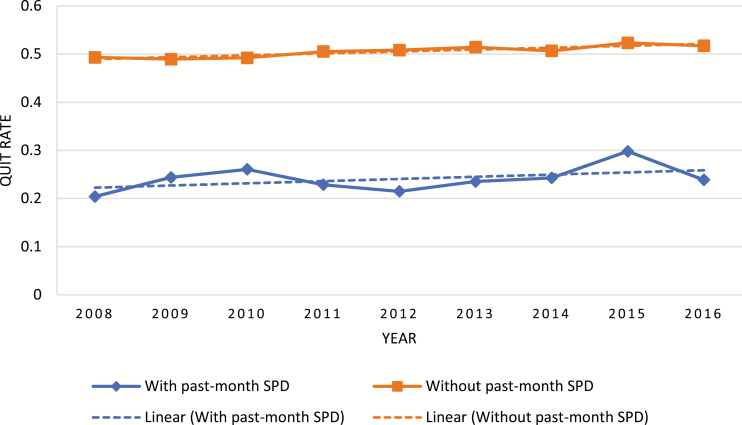

In unadjusted analyses, cigarette quit rates did not change from 2008 to 2016 among persons with past-month SPD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.99 to 1.06, p = .224), whereas cigarette quit rates increased from 2008 to 2016 among individuals without past-month SPD (OR = 1.02; 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.02, p < .001; Supplementary Table 1). After adjusting for potential confounders, cigarette quit rates did not change from 2008 to 2016 among individuals with (aOR = 1.01; 95% CI = 0.97 to 1.05, p = .667) or without past-month SPD (aOR = 1.00; 95% CI = 0.99 to 1.01, p = .441). Time and SPD did not interact in unadjusted (F(1,110) = 0.16, p = .693) or adjusted (F(1,110) = 0.09, p = .771) analyses. At each year, those with past-month SPD had lower quit rates compared with those without past-month SPD (all p’s < .001; Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cigarette quit rates from 2008 to 2016 for respondents with and without past-month serious psychological distress (SPD), aged 26 years or older. Quit rate was defined as the proportion of former smokers among ever smokers. Abbreviation: SPD = serious psychological distress.

Discussion

This study used nationally representative data to examine cigarette smoking quit rates from 2008 to 2016 among US adults with and without past-month SPD. First, quit rates among those with past-month SPD were consistently lower (by approximately half) than quit rates for those without SPD at each year, including most recently in 2016. Second, from 2008 to 2016, cigarette smoking quit rates increased over time among those without past-month SPD, but remained unchanged among those with past-month SPD. There were no gender, age, race/ethnicity, or income differences in quit rate over time by SPD status.

Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations should be noted. First, our findings may not generalize to groups outside of the United States. Second, these findings are limited to self-reported cigarette use without biochemical verification. Third, abstinence from non-cigarette tobacco products was not examined. Finally, given the cross-sectional design of the NSDUH, it is not possible to investigate causality. Our study’s strengths included the use of nationally representative data across multiple years to examine recent time trends. To the best of our knowledge, other studies have not examined this question using data after 2012. Further, we used an acute measure of SPD (ie, past month) that may be a more sensitive indicator of psychological distress than the more commonly reported past year measure.

Interpretation

These data provide new insight into findings from earlier studies14,15 demonstrating that the smoking prevalence is not declining among those with serious mental health problems by showing that one possible contributing factor for this lack of or slowed decline in smoking among those with SPD is a significantly lower and stable quit rate; a pattern inconsistent with what is seen over time in the general population.2 Our data are also consistent with and extend findings from prior cross-sectional literature indicating that lower tobacco quit rates prevail among those with serious mental health problems.6–8 Given that this pattern does not appear to be due to a lack of interest in quitting, motivation, or lack of response to standard cessation treatments,5,16 other reasons must be considered. One possibility is that there may be differences in whether and to what degree persons with SPD are in contact with clinical care and/or, even if they are, they may be less likely to be offered smoking cessation treatment in these settings. Another possible contributing factor could be that persons with SPD are less likely to be seen in medical treatment settings—primary or specialty care—than those without SPD due to fewer financial resources. Interestingly, results from representative population surveys in the United States and Australia have concluded that the majority of individuals with mental illness were not in contact with mental health services, yet these individuals did not have differing smoking rates compared with those who did access services for their mental health problem,10 therefore access to these forms of treatment do not appear to contribute though it is still possible that access to smoking cessation services differ. Evidence also suggests that community-based approaches (eg, quit lines17,18) may not be as effective for persons with SPD as mental health problems appear to be a barrier to smoking cessation, and many such tobacco control measures do not include mental health treatment. More information is needed on the quitting behaviors of persons with and without SPD to better understand these persisting discrepancies.

We also found no differences in smoking quit rates over time by SPD status for specific demographic subgroups in contrast to mixed results in past studies. A prior study of more than 480 000 US adults that examined the association between SPD and current smoking prevalence reported no interactions with gender, age, or race/ethnicity,3 whereas other studies suggested differences in the associations between SPD and smoking behavior by gender, age, or race/ethnicity.19,20 For example, in a national sample of 5718 US persons, an association was found between general psychological distress and smoking behavior (eg, current smoking prevalence and cigarettes per day) among NH White respondents but not NH Black or Hispanic respondents.20 The literature on demographic differences in the relationship between SPD and smoking appears mixed and will require additional research to draw conclusions.

Conclusions

Quit rates did not increase from 2008 to 2016 among persons with SPD, whereas an increase in quit rate was observed among those without SPD over the same period. Further, the absolute cigarette quit rates among those with SPD were consistently lower than those without SPD at each year of evaluation across all demographic groups, suggesting that mental health disparities in smoking persist and may even be increasing. Intervention and public health efforts to improve quit rates should focus on those with mental health problems.

Declaration of Interests

No authors have conflicts of interest to declare. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA) (grant R01-DA20892 to RDG). NIH and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

- 1.Williams JM, Steinberg ML, Griffiths KG, Cooperman N. Smokers with behavioral health comorbidity should be designated a tobacco use disparity group. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1549–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDHHS. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2014. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forman-Hoffman VL, Hedden SL, Miller GK, Brown K, Teich J, Gfroerer J. Trends in cigarette use, by serious psychological distress status in the United States, 1998-2013. Addict Behav. 2017;64:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt LA, Dey AN, Cohen AJ. Characteristics of adults with serious psychological distress as measured by the K6 scale: United States, 2001–04. Adv Data. 2007;(382):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulik MC, Glantz SA. Softening among U.S. Smokers with psychological distress: more quit attempts and lower consumption as smoking drops. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6):810–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung HY, Prochaska JJ, Ong MK, Shi Y, Max W. Cigarette smoking and serious psychological distress: a population-based study of California adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1183–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasheen C, Hedden SL, Forman-Hoffman VL, Colpe LJ. Cigarette smoking behaviors among adults with serious mental illness in a nationally representative sample. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(10):776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagman BT, Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Williams JM. Tobacco use among those with serious psychological distress: results from the national survey of drug use and health, 2002. Addict Behav. 2008;33(4):582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of Physicians RCoP. Smoking and Mental Health. London: RCP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9 (285):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Leon J, Diaz FJ, Rogers T, Browne D, Dinsmore L. Initiation of daily smoking and nicotine dependence in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Schizophr Res. 2002;56(1–2):47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samhsa. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 767 2013. Codebook. Rockville, MD; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence D, Williams JM. Trends in smoking rates by level of psychological distress-time series analysis of US National Health Interview Survey data 1997-2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(6):1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts E, Eden Evins A, McNeill A, Robson D. Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Addiction. 2016;111(4):599–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris CD, Tedeschi GJ, Waxmonsky JA, May M, Giese AA. Tobacco quitlines and persons with mental illnesses: perspective, practice, and direction. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2009;15(1):32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukowski AV, Morris CD, Young SE, Tinkelman D. Quitline outcomes for smokers in 6 states: rates of successful quitting vary by mental health status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(8):924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peiper N, Rodu B. Evidence of sex differences in the relationship between current tobacco use and past-year serious psychological distress: 2005–2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(8):1261–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiviniemi MT, Orom H, Giovino GA. Psychological distress and smoking behavior: the nature of the relation differs by race/ethnicity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(2):113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.