Abstract

Background

Cognitive decline occurs in all persons during the aging process and drugs can only alleviate symptoms and are expensive. Some researches demonstrated that Tai Chi had potential in preventing cognitive decline while others' results showed Tai Chi had no influence on cognitive impairment. Therefore, we conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the efficacy and safety of cognitive impairment patients practicing Tai Chi.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was carried out in multiple databases, including PubMed, Cochrane, MEDLINE (Ovid), Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, PsycInfo (Ovid), CKNI, Wan Fang, VIP, SinoMed, and ClinicalTrails, from their inception to 1 July 2020 to collect randomized controlled trials about practicing Tai Chi for patients with cognitive impairment. Primary outcomes included changes of cognitive function and secondary outcomes included changes of memory functions. Data were extracted by two independent individuals and Cochrane Risk of Bias tool version 2.0 was applied for the included studies. Systematic review and meta-analysis were performed by RevMan 5.3 software.

Results

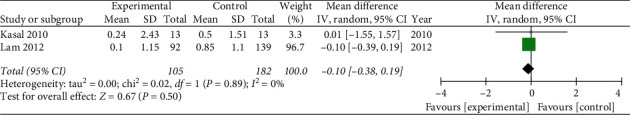

The results included 827 cases in 9 studies, of which 375 were in the experimental group and 452 were in the control group. Meta-analysis showed that Mini-Mental State Examination WMD = 1.52, 95% CI [0.90, 2.14]; Montreal Cognitive Assessment WMD = 3.5, 95% CI [0.76, 6.24]; Clinical Dementia Rating WMD = −0.55, 95% CI [−0.80, −0.29]; logical memory delayed recall WMD = 1.1, 95% CI [0.04, 2.16]; digit span forward WMD = 0.53, 95% CI [−0.65, 1.71]; and digit span backward WMD = −0.1, 95% CI [−0.38, 0.19]. No adverse events were reported in the included articles.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence to support that practicing Tai Chi is effective for older adults with cognitive impairment. Tai Chi seems to be a safe exercise, which can bring better changes in cognitive function score.

1. Introduction

While social aging is a trend, cognitive decline can occur for everyone. Eventually, this may result in mild cognitive impairment and dementia [1]. Mild cognitive impairment occurs along a continuum from normal cognition to dementia [2]. It is widely recognized as the intermediate stage of cognitive impairment between the changes seen in normal cognitive aging and dementia [3]. At present, drugs for cognitive impairment can only alleviate the symptoms of cognitive disorders and their price is usually high. Therefore, complementary and alternative therapies have become a hot research topic for improving cognitive impairment in recent years [4].

Tai Chi has a long history and culture. Participants take deep breathing and mental concentration in order to carrying out smooth and continuous body movements [5]. It combines Chinese martial arts and meditative movements that promote balance of mind and body for healing [6]. Physical exercise and fitness have been proposed as potential factors that may promote healthy cognitive aging [7] and aerobic exercise was proven to improve cognitive function in adults with neurological disorders [8]. In recent years, long-term cognitive training and physical exercise had been confirmed its benefits for delaying the cognitive decline for the elderly [9, 10]. Tai Chi might improve memory and executive function in older adults with amnestic-mild cognitive impairment, possibly via an upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor [11, 12]. The studies suggested Tai Chi has impacts on global cognitive functions, visuospatial skills, semantic memory, verbal learning memory, and self-perception of memory [13]. It may also have direct benefits on enhancing attention and executive functions [14].

At present, a growing body of evidence supports that Tai Chi may help improve cognitive function and mental well-being for older adults with mild dementia [15, 16]. It also proved that Tai Chi has psychophysiological benefits for motor coordination and memory [17–20]. However, some studies reported no significant differences in assessment of cognitive function [21]. Previous meta-analysis revealed that Tai Chi had no influence on individuals with cognitive impairment [22]. In addition, previous meta-analysis only searched the English databases [23] while Tai Chi is most practiced in China. Therefore, we will conduct a meta-analysis and systematic review without language limitation to assess the effect of Tai Chi on cognitive function among older adults with cognitive impairment.

2. Information and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) of 2015 guideline [24]. The protocol was registered at PROSPERO (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO), registration number: CRD42020171559.

2.2. Search Strategy

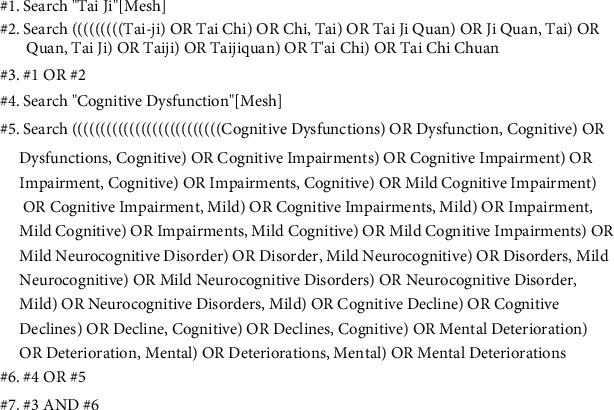

Electronic literature searches were performed in the database of PubMed, Cochrane, MEDLINE (Ovid), Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, PsycInfo (Ovid), CKNI, Wan Fang, VIP, SinoMed, and ClinicalTrails from inception to July 2020. Search strategy of PubMed is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

(a) Published literature; (b) RCTs; (c) inclusion of people with cognitive impairment; (d) people over 65 years old according to classification for older adults by World Health Organization in 2020 [25]; (e) practicing Tai Chi for more than one month but no more than one year; (f) interventions using Tai Chi as a main treatment; the combination therapy of Tai Chi and other interventions compared with the same other interventions alone were also included; and (g) reporting more than one of the following primary or secondary outcomes.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

(a) Nonclinical studies (experimental and basic studies); (b) observational or retrospective studies; (c) lack of sufficient information on baseline or primary or secondary outcome data; (d) narrative reviews, systematic reviews, case reports, letters, editorials, clinical guidelines, and commentaries.

2.5. Primary Outcome

Any change in cognitive function (such as MMSE, MoCA, and CDR).

2.6. Secondary Outcome

Any change in memory function (such as LMD, DSF, and DSB).

2.7. Patient and Public Involvement

Neither patients nor public were involved in the design of this study. This systematic review and meta-analysis did not recruit any patients.

2.8. Data Collection

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers (RG and YG) using a standardized form including study demographics, baseline characteristics, study design, intervention methods, outcome measures, and results. We resolved any disagreement through discussion and we consulted a third review author (CZ or XL).

2.9. Bias Risk Assessment

According to the risk of bias assessment tool from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019), two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of the included study, and any conflicts were resolved through consensus. Bias risk assessment was evaluated from the following seven items: random sequence generation, assignment concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. These items are described as green, yellow, and red colors and “+”, “−”, and “?”. The symbols indicate “low”, “high”, and “unclear” risk of bias.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by using Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI were used as the effect quantity to merge the continuous variables included in the study. P value and I2 statistic were used to test heterogeneity between trial results. When more than two articles were included, heterogeneity was considered. If the I2 was >50%, the random effect model was applied according to the clinical heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis was used to evaluate the source of heterogeneity. The statistical calculation process was completed by RevMan 5.3 software.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

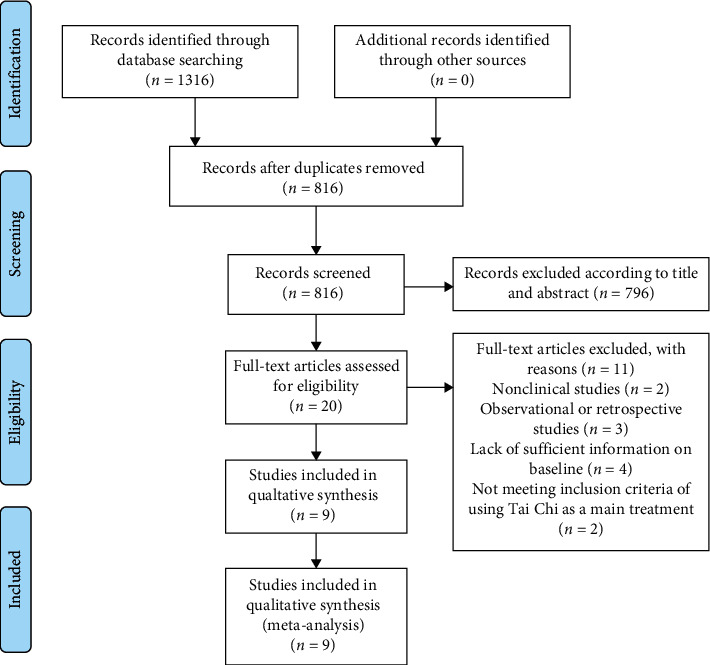

Initial searches generated 1316 related literatures. According to the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, 9 literatures were included [16, 21, 26–32] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of study selection.

3.2. Characteristics of the Study

Nine articles [16, 21, 26–32] contained 375 cases in the experimental group and 452 cases in the control group (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the literatures.

| Study | Exp. average age/range | Exp. group number | Con. average age/range | Con. group number | Exp. group method | Con. group method | Duration of Tai Chi | Country | Measure | Research designs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kasal 2010 [26] | 73.54 | 13 | 74.54 | 13 | Tai Chi | N/A | 6 months | Brazil | 5.6 | RCT |

| Lam 2012 [27] | 77.2 | 92 | 78.3 | 169 | Tai Chi + stretching and relaxation exercises | Stretching and relaxation exercises | 12 months | China | 1.3.4.5.6 | RCT |

| Li 2014 [28] | 75 | 22 | 77 | 24 | Tai Chi | N/A | 14 weeks | China | 1 | RCT |

| Tai 2016 [21] | 70.21 | 14 | 76.3 | 10 | Tai Chi | Nonhealth-related social activities | 6 weeks | China | 1.3 | RCT |

| Sungkarat 2017 [29] | 68.3 | 33 | 67.5 | 33 | Tai Chi + education | Education | 15 weeks | Thailand | 4 | RCT |

| Siu 2018 [30] | — | 80 | — | 80 | Tai Chi | N/A | 16 weeks | China | 1 | RCT |

| Huang 2019 [16] | 81.9 | 36 | 81.9 | 38 | Tai Chi + routine treatments | Routine treatments | 10 months | China | 1.2 | RCT |

| Wang 2019 [31] | 65–69 (3) 70–79 (32) 80–85 (11) |

54 | 65–69 (2) 70–79 (30) 80–85 (16) |

54 | Tai Chi | N/A | 6 months | China | 1.4 | RCT |

| Bao 2019 [32] | 65.62 | 31 | 68.22 | 31 | Tai Chi + health education | Health education | 6 months | China | 1.2 | RCT |

Measure: 1, Mini-Mental State Examination; 2, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; 3, Clinical Dementia Rating; 4, logical memory delayed recall score; 5, digit span forward; 6, digit span backward.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the literature's inclusion criteria of cognitive impairment.

| Study | Inclusion criteria of cognitive impairment | Style of Tai Chi |

|---|---|---|

| Kasal 2010 [26] | (i) Memory complaint offered by the patient or by family members over the previous year; (ii) screening score of the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test lower than 10; (iii) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) within normality, corrected by educational level | Yang style |

| Lam 2012 [27] | (i) CDR of 0.5 or (ii) neuropsychological criteria for amnestic-mild cognitive impairment (MCI) with subjective cognitive complaints [21]; objective memory impairment with reference to delayed recall of list learning test at greater than or equal to 1.5 SD below education- and age-matched subjects with CDR 0; (iii) no previous regular practice of Tai Chi or other mind-body exercise for more than 6 months | Yang 24-form style |

| Li 2014 [28] | (i) Having MMSE scores between 20 and 30 | N/A |

| Tai 2016 [21] | (i) Alzheimer with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0.5–1; (ii) upper limb mobility sufficient to perform requisite finger-pointing tasks, such as flexing and extending the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and fingers | Yang style |

| Sungkarat 2017 [29] | (i) Petersen's criteria for diagnosing amnestic multiple-domain MCI (a-MCI) had scores of 24 or greater on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and less than 26 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), had adequate memory if cued, and comprehended instructions required for study participation | 10-form style |

| Siu 2018 [30] | (i) The CMMSE screening score ranging from 19 to 28, which was corrected based on educational level (≥18 for illiterate respondents and ≥22 for those having received more than two years of schooling) | Yang style |

| Huang 2019 [16] | (i) Diagnosed with dementia based on the diagnostic criteria 128 of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental 129 Disorders, 4th edition; (ii) a clinical dementia 130 rating score <2 | N/A |

| Wang 2019 [31] | (i) According to the diagnostic criteria set by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association (NIA, AA), the patients were screened as MCI, i.e., subjective cognitive function: the patients who complained or knew about cognitive impairment; (ii) objective cognitive function: according to the Peking Union Medical College, version of the total score of MoCA-p is 25 for the elderly aged 65–79 and 2l–24 for the elderly aged 80–85; (iii) the total score of activities of daily living (ADL) is ≤26, and the complex engineering daily living (ADL) is ≥10 | 8-form style |

| Bao 2019 [32] | (i) Having memory decline; (ii) the course of disease was more than 3 months; Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) was 2–3, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale was 0.5, memory test score was below 1.5 standard deviation of age and education matched control group, MMSE score met illiteracy (18–21), primary school culture (21–24), secondary school culture (25–27), and daily life ability score was lower than 26; (iii) memory impairment and other aspects of cognitive function retention | Yang style |

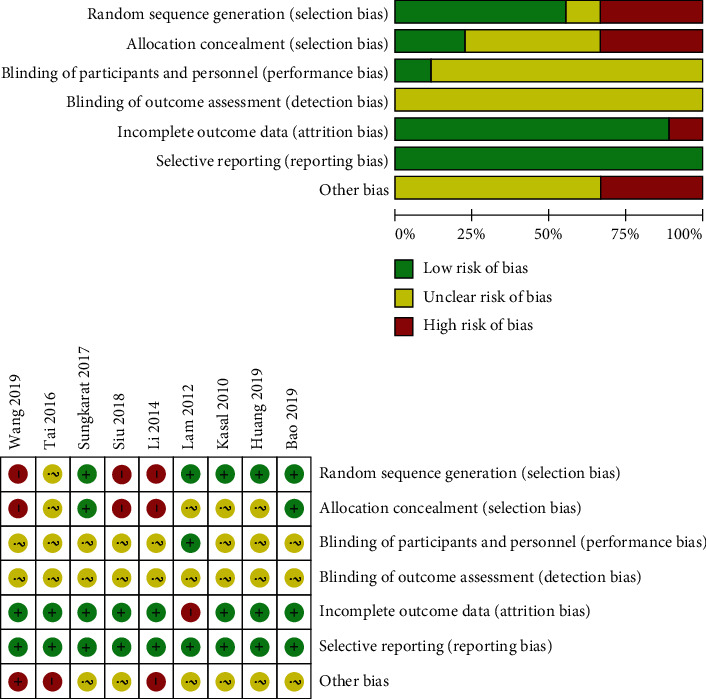

3.3. Risk of Bias

The results of the risk of bias assessment of the 9 studies [16, 21, 26–32] are summarized in Figure 3. Three literatures [28, 29, 31] were scored as high risk without using random sequence generation. All literatures did not describe detection bias. One article [27] was scored as high risk with incomplete outcome data. All trials measured outcomes listed in their studies and reported on all expected outcome measures of interest (low risk of bias).

Figure 3.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

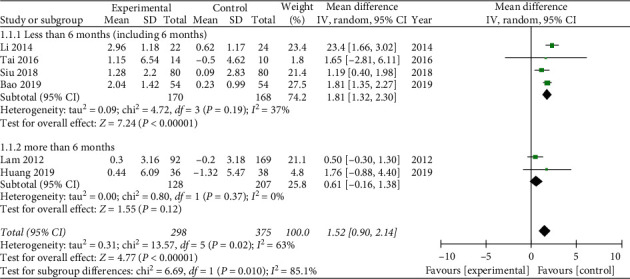

3.4. Mini-Mental State Examination

Six literatures [16, 21, 27, 28, 30, 32] reported the MMSE. Subgroup analysis was carried to analyze heterogeneity. American Academy of Neurology guideline reported that short-term exercise training (6 months) is likely to improve cognitive measure [35]. Therefore, we divide MMSE into different time periods in order to assessing short-term (less than 6 months) and long-term (more than 6 months) effects. In terms of practicing Tai Chi for less than 6 months (including 6 months), the combined effect is WMD = 1.81, 95% CI [1.32, 2.30], P < 0.05. The data were statistically significant. On the other hand, the result of practicing Tai Chi for more than 6 months is WMD = 0.61, 95% CI [−0.16, 1.38], P=0.12, which was not statistically significant. The total combined effect is WMD = 1.52, 95% CI [0.90, 2.14], I2 = 63%, and the data were statistically significant. It indicated that practicing Tai Chi less than 6 months (including 6 months) might improve MMSE for patients with cognitive impairment (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of Mini-Mental State Examination.

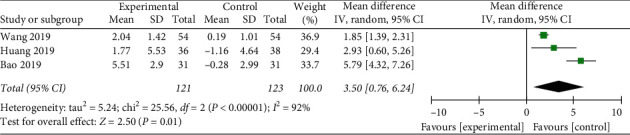

3.5. Montreal Cognitive Assessment

Three literatures described the MoCA [16, 31, 32]. The combined effect was WMD = 3.5, 95% CI [0.76, 6.24], P < 0.05. The data was statistically significant (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

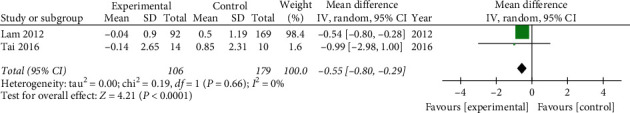

3.6. Clinical Dementia Rating

Two literatures reported CDR [21, 27]. The combined effect was WMD = −0.55, 95% CI [−0.80, −0.29], P < 0.05, which was statistically significant (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of Clinical Dementia Rating.

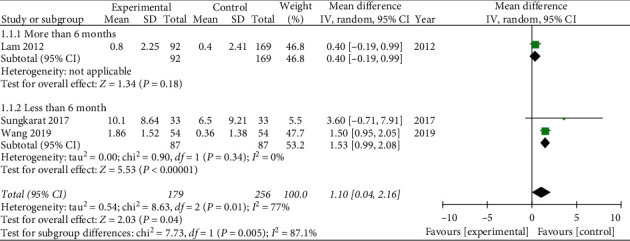

3.7. Logical Memory Delayed Recall Score

Three literatures reported LMD [27, 29, 31]. One article [27] described practicing Tai Chi for more than 6 months, and the MD = 0.4, 95% CI [−0.19, 0.99], P=0.18, which had no statistical significance. In terms of practicing Tai Chi for less than 6 months, WMD = 1.53, 95% CI [0.99, 2.08], P < 0.05. The result was statistically significant, and it indicated that practicing Tai Chi less than 6 months might improve LMD (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot of logical memory delayed recall score.

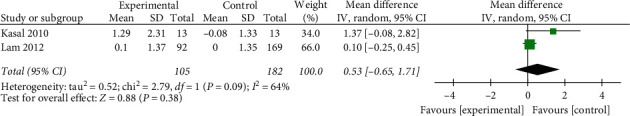

3.8. Digit Span Forward

Two experiments [26, 27] mentioned DSF, and the combined effect amount was WMD = 0.53, 95% CI [−0.65, 1.71], P=0.38. It included 105 cases in the experimental group and 182 cases in the control group. The comparison results were not statistically significant and the evidence level was low (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Forest plot of digit span forward.

3.9. Digit Span Backward

DSB was included in two articles [26, 27]. The combined effect amount was WMD = −0.1, 95% CI [−0.38, 0.19], P=0.5. It had no statistical significance (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Forest plot of digit span backward.

3.10. Adverse Events

No article reported the adverse events of Tai Chi.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

The objective of this review was to summarize and evaluate the effectiveness of Tai Chi for cognitive impairment. Nine researches including 827 patients were carried out in China, Brazil, and Thailand. The evidence shows that Tai Chi is more likely to improve cognitive impairment comparing to control group. We found statistically significant benefits of Tai Chi as follows: MMSE WMD = 1.52, 95% CI [0.90, 2.14]; MoCA WMD = 3.5, 95% CI [0.76, 6.24]; CDR WMD = −0.55, 95% CI [−0.80, −0.29]; LMD WMD = 1.1, 95% CI [0.04, 2.16]. However, DSF WMD = 0.53, 95% CI [−0.65, 1.71], and DSB WMD = −0.1, 95% CI [−0.38, 0.19], were not statistically significant. In addition, there is no research reporting the adverse events of Tai Chi and it may be a safe exercise for people with cognitive impairment.

4.2. Applicability of the Current Evidence

Previous Cochrane Review showed Tai Chi did significantly reduce risk of falling [4], but it did not analyze any influence on cognitive impairment. It had been affirmed that exercising activities play a positive role in declining risk of the elderly [14, 33], but the effect of Tai Chi was uncertain. Other correlative meta-analyses only focused on English databases [14, 36]. We added studies from Chinese databases in our systematic review. Therefore, this study is an update meta-analysis which evaluates the role of Tai Chi in the prevention of cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment is a long-term process [2] and it is often considered irreversible [37]. In recent years, performing Tai Chi has been stressed in the process of preventing cognitive impairment [34]. Our research finds that practicing Tai Chi is helpful for cognitive function, but it seems to have no effect on logical memory. Considering that the test results are not necessarily positively correlated with clinical symptoms and conditions, this study only provides reference for clinical practice.

4.3. Limitations of This Review

Although new published literatures were added to this systematic review, the risk of this limitation has not been avoided. First, according to Cochrane's bias risk assessment tool, 5 of the 9 included studies are considered to have a high bias risk due to the lack of randomization, blind method implementation, and distribution concealment. The quality of evidence is not good enough because most researches did not describe the detailed methods in their research. Second, the type of Tai Chi was not assessed in this study according to lack of related RCTs. Third, different severity of cognitive impairment may lead to different effects by performing Tai Chi, but no article mentioned that.

4.4. Implications for Further Studies

This study provides a certain value for the future research [38]. The current data show that the Tai Chi group has better cognitive function score than the control group and Tai Chi is a safe exercise. In terms of clinical rehabilitation, more long-term follow-ups are needed to provide more RCTs and mechanical researches. In addition, most of the included studies either inadequately reported or did not clearly report methods related to important biases such as randomization/allocation concealment and blinding methods. Future trials should be improved for their reporting quality by following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement [39].

5. Conclusion

There is limited evidence supporting that practicing Tai Chi can bring better changes in cognitive function score (MMSE, MoCA, CDR, and LMD). However, there is no influence on DSF and DSB. Current evidence indicates that Tai Chi is a safe exercise for people with cognitive impairment. There is still a need for increasing RCTs to address whether practicing Tai Chi is effective for patients with cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Jiangsu Leading Talents Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SLJ0226).

Abbreviations

- MMSE:

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA:

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- CDR:

Clinical Dementia Rating

- LMD:

Logical memory delayed recall

- DSF:

Digit span forward

- DSB:

Digit span backward

- RCT:

Randomized controlled trial.

Data Availability

No primary data were used in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors of this study have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Gu Renjun and Gao Yujia worked equally in this article. Sun Zhiguang and Gu Renjun conceived and designed the analysis. Gu Renjun, Gao Yujia, Zhang Chunbing, and Liu Xiaojuan completed the data retrieval and analyzed the data. Gu Renjun wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

References

- 1.Morley J. E. An overview of cognitive impairment. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2018;34(4):505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanford A. M. Mild cognitive impairment. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2017;33(3):325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vega J. N., Newhouse P. A. Mild cognitive impairment: diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;16(10):p. 490. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0490-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forbes D., Forbes S., Morgan D. G., Markle-Reid M., Wood J., Culum I. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database System Reviews. 2008;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd006489.pub2.CD006489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyman S. R., Ingram W., Sanders J., et al. Randomised controlled trial of the effect of tai chi on postural balance of people with dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2019;14:2017–2029. doi: 10.2147/cia.s228931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F., Lee E.-K. O., Wu T., et al. The effects of tai chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;21(4):605–617. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller D. I., Taler V., Davidson P. S., Messier C. Measuring the impact of exercise on cognitive aging: methodological issues. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33(3):p. 622. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonnell M. N., Smith A. E., Mackintosh S. F. Aerobic exercise to improve cognitive function in adults with neurological disorders: a systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92(7):1044–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen R. C., Caracciolo B., Brayne C., Gauthier S., Jelic V., Fratiglioni L. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2014;275(3):214–228. doi: 10.1111/joim.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise interventions on cognitive and physiologic adaptations for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(24):p. 9216. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng P. W. H. Tai chi and chronic pain. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2012;37(4):372–382. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e31824f6629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sungkarat S., Boripuntakul S., Kumfu S., Lord S. R., Chattipakorn N. Tai chi improves cognition and plasma BDNF in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2018;32(2):142–149. doi: 10.1177/1545968317753682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim K., Pysklywec A., Plante M., Demers L. The effectiveness of Tai Chi for short-term cognitive function improvement in the early stages of dementia in the elderly: a systematic literature review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2019;14:827–839. doi: 10.2147/cia.s202055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wayne P. M., Walsh J. N., Taylor-Piliae R. E., et al. Effect of tai chi on cognitive performance in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein P. J., Baumgarden J., Schneider R. Qigong and tai chi as therapeutic exercise: survey of systematic reviews and meta-analyses addressing physical health conditions. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2019;25(5):48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang N., Li W., Rong X., et al. Effects of a modified tai chi program on older people with mild dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019;72(3):947–956. doi: 10.3233/jad-190487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huston P., McFarlane B. Health benefits of tai chi: what is the evidence? Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(11):881–890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saeed S. A., Antonacci D. J., Bloch R. M. Exercise, yoga, and meditation for depressive and anxiety disorders. American Family Physician. 2010;81(8):981–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho R. T., Fong T. C., Wan A. H., et al. A randomized controlled trial on the psychophysiological effects of physical exercise and Tai-chi in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2016;171(1-3):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao J., Chen X., Egorova N., et al. Tai Chi Chuan and baduanjin practice modulates functional connectivity of the cognitive control network in older adults. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/srep41581.41581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai S.-Y., Hsu C.-L., Huang S.-W., Ma T.-C., Hsieh W.-C., Yang Y.-H. Effects of multiple training modalities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2016;12:2843–2849. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s116257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S., Yin H., Jia Y., Zhao L., Wang L., Chen L. Effects of mind-body exercise on cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2018;206(12):913–924. doi: 10.1097/nmd.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen M.-L., Wotiz S. B., Banks S. M., Connors S. A., Shi Y. Dose-response association of tai chi and cognition among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(6):p. 3179. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2016;354:p. i4086. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bull F. C., Al-Ansari S. S., Biddle S., et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;54(24):1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasai J. Y. T., Busse A. L., Magaldi R. M., et al. Effects of Tai Chi Chuan on cognition of elderly women with mild cognitive impairment. Einstein (São Paulo) 2010;8(1):40–45. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082010ao1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam L. C., Chau R. C., Wong B. M., et al. A 1-year randomized controlled trial comparing mind body exercise (Tai Chi) with stretching and toning exercise on cognitive function in older Chinese adults at risk of cognitive decline. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(6):p. 568. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li F., Harmer P., Liu Y., Chou L.-S. Tai Ji Quan and global cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2014;58(3):434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sungkarat S., Boripuntakul S., Chattipakorn N., Watcharasaksilp K., Lord S. R. Effects of tai chi on cognition and fall risk in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2017;65(4):721–727. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu M.-Y., Lee D. T. F. Effects of tai chi on cognition and instrumental activities of daily living in community dwelling older people with mild cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(1):p. 37. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0720-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Q., Sheng Y. Time effect analysis of Taijiquan on cognitive function of patients with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019;19(2):141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bao N., Liu C. Study on the influence of Taijiquan on the cognitive function of patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Medical Information. 2019;32(2):115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Northey J. M., Cherbuin N., Pumpa K. L., Smee D. J., Rattray B. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(3):154–160. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zeng Y., Xie X., Cheng A. S. K. Qigong or tai chi in cancer care: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Oncology Reports. 2019;21(6):p. 48. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0786-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen R. C., Lopez O., Armstrong M. J., et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2018;90(3):126–135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000004826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly M. E., Loughrey D., Lawlor B. A., Robertson I. H., Walsh C., Brennan S. The impact of exercise on the cognitive functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews. 2014;16:12–31. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen R. C. Mild cognitive impairment. Continuum. 2016;22:404–418. doi: 10.1212/con.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng G., Liu F., Li S., Huang M., Tao J., Chen L. Tai chi and the protection of cognitive ability. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz K. F., Altman D. G., Altman D. G., Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Medicine. 2010;8(1):p. 18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Data Availability Statement

No primary data were used in this article.