Abstract

Adoption of certain behavioral and social routines that organize and structure the home environment may help families navigate the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. The current cross-sectional study aimed to assess family routines prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic and examine associations with individual and family well-being. Using a national sample, 300 caregivers of children ages 6-18 were surveyed using Amazon Mechanical Turk platform during the first three months of COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Caregivers reported on family demographics, COVID-19-related stress, engagement in family routines (prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic), stress mindset, self-efficacy, and family resiliency. Overall, families reported engaging in fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic. COVID-19-related stress was highest in low-income families, families of healthcare workers, and among caregivers who had experienced the COVID-19 virus. Moreover, COVID-19-related stress was negatively related to self-efficacy, positively related to an enhancing stress mindset, and negatively related to family resilience. Engagement in family routines buffered relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience, such that COVID-19-related stress was not associated with lower family resilience among families that engaged in high levels of family routines. Results suggest that family routines were challenging to maintain in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, but were associated with better individual and family well-being during this period of acute health, economic, and social stress.

Keywords: COVID-19, Family, Routines, Resilience, Stress, Stress mindset

Highlights

Families reported engaging in fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, when compared to prior to the pandemic.

Families reported significant reductions in child bedtime routines and screen time limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic, when compared to prior to the pandemic.

Engagement in family routines buffered the impact of stress on family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The onset of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic was a major public health event characterized by unprecedented disruptions to daily life in the United States and around the world. By April of 2020, 48/50 states enacted state-wide school/school district closures for the entire academic year (Education Week, 2020) and 45/50 states issued local or state-wide stay-at-home orders (NBC News, 2020). These dramatic changes to daily life, occurring in the context of economic and health uncertainty, posed notable challenges to the psychological well-being of individuals of all ages. Negative effects may include post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger (Brooks et al., 2020). Indeed, a preliminary poll of US adults in March 2020 found that nearly half of respondents endorsed that their life had changed in a “major way” due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by May of 2020, one third of poll respondents reported high levels of psychological distress (Pew Research Center, 2020).

Despite emerging information of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, the impact on families is still largely unknown. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread, people across the world were forced to quarantine to their homes to prevent spreading the virus. Resources outside of the home, including schools, workplaces, community resources (e.g., childcare, parks/recreation, churches), and even extended family members, were increasingly limited, modified (e.g., relying on virtual technology), or were altogether unavailable. In the absence of other contextual influences, the influence of the home environment on caregiver and family functioning was likely greater than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent conceptual model proposed by Prime et al., 2020 delineates the way in which social disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic may pose acute risks to family, caregiver, and child wellbeing. According to this model, social disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic may impact individual family members (e.g., caregivers) as well as dyadic relationships (e.g., caregiver-child, marital relationships) and whole family processes (e.g., routines, communication; Prime et al., 2020). Therefore, children may be impacted by seemingly distal social stressors through a cascading effect of psychological distress that occurs through dyadic relationships and family processes. For example, changes at work, financial strain, and/or novel parenting responsibilities (e.g., homeschooling) during the COVID-19 pandemic may place additional demands on adult caregivers. Indeed, a longitudinal self-report study of parents of adolescents at the beginning of confinement in Spain demonstrated that those who had lost their job, had prior psychological problems, or lost someone to the pandemic showed worse emotional adjustment (Valero-Moreno et al., 2021). These increased demands threaten to overwhelm caregivers’ internal resources (e.g., beliefs, cognitions) and may impede caregivers’ abilities to engage in consistent parenting strategies (e.g., planning, monitoring, limit-setting). Changes in parenting strategies may weaken the caregiver-child relationship and impact family processes (e.g., reduced communication, support), which increases risk for psychological distress in the child. Notably, Daks and colleagues surveyed 742 co-parents in March-April of 2020 and found that parent inflexibility associated with less family cohesion, more family discord, and less utilization of constructive parenting strategies (Daks et al., 2020). Thus, the social disruptions that encompass the COVID-19 pandemic may impact family processes and functioning.

Family resilience is one form of family functioning that is particularly relevant to explore in the context of stress, as it emphasizes how protective factors can be engaged to in to overcome adverse situations (Benzies & Mychasiuk, 2009). By focusing on the ways in which risk and protective factors interact within the family system, family resilience emphasizes how the family as a whole—rather than individual family members—adapts in the face of stress (Hawley & DeHaan, 1996). In addition, family resilience is more comprehensive than family strengths which focus on the specific resources (e.g., belief systems) that might be applied to various stressors (Henry et al., 2015). Due to the significant family disruptions and stressors caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding factors associated with families who demonstrate resilience during this period is important.

Establishing and/or maintaining certain behavioral and social routines may help families navigate the challenges associated with disruptions to daily life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Routines are practices involving at least two family members (usually parent and child) that are performed with predictability and regularity (e.g., family mealtimes, bedtime rituals; Fiese, 2006; Fiese et al., 2002). Families that successfully establish routines, including regular mealtimes and bedtimes, demonstrate positive psychological and physical health outcomes (Miller et al., 2015; Utter et al., 2018). Moreover, family structure and routines may have increased importance during times of stress. For example, among families exposed to traumatic neighborhood stress, higher ratings of family structure organization were related to fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors among youth (Kiser et al., 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic may present an optimal time for families to engage in routines as other contexts (e.g., school, work, extra-curricular activities) were abruptly removed leaving the family context at the center of daily life. Yet, despite the well-established benefits of behavioral and social routines, only one study to date has investigated family routines in the context of COVID-19. Utilizing a sample of children aged 2.6–6 years collected in May/June of 2020, a cross-sectional study reported that family routines, as measured using the Family Routines Inventory (Jensen et al., 1983), were strongly associated with lower levels of both externalizing behaviors and lower depressive symptoms in children even after covarying dual-parent structure, food insecurity, and income (Glynn et al., 2021). These findings suggest that family routines are associated with better mental health among children, but to date, nothing is known about how routines may relate to family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Numerous challenges, however, may interfere with families’ ability to engage in behavioral and social routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. During “typical” times, the implementation of routines is partly dictated by social structures outside of the home, including work, school, and activity schedules (Brazendale et al. 2017), most of which were limited during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Moreover, socioeconomic factors including inconsistent or demanding work schedules have previously been shown to limit families’ ability to participate in positive routines (Davison & Birch, 2001), and this may play a role for individuals and families who experienced changes in work status or schedules during the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic also presented novel challenges that have not yet been explored in research, including competing demands of working from home and homeschooling, limitations on childcare, and the unique situations of essential workers. Additionally, the number of children in the home, as well as the isolation status of the family, may influence the extent to which families prioritized routines relative to other competing demands. Therefore, it is essential to consider not only family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, but also caregivers’ internal resources that may influence engagement in potentially protective behaviors.

Two caregiver internal resources that may be of particular relevance during the COVID-19 pandemic are stress mindset and self-efficacy. Stress mindset is an individual’s understanding of the potential positive or negative consequences of stress (Crum et al., 2013). Individuals can view stress as either enhancing or debilitating to various outcomes (e.g., performance and productivity, health and well-being, learning and growth) (Crum et al., 2013). Individuals who endorse a stress as an enhancing mindset are associated with more positive affect, attention towards positive stimuli, and cognitive flexibility compared to a stress-is-debilitating mindset (Crumet al., 2017). This frame may be particularly important to consider during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a caregiver’s views regarding the helpfulness or harm of the present stressful experience might affect the relation between COVID-19 stress and family resilience. Specifically, stress mindset could serve as a protective factor between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. Similarly, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to complete or perform a behavior (Bandura, 1997; Salsman et al., 2019). In the face of stressful experiences, higher levels of self-efficacy are associated with reduced psychological distress (Luszczynska et al., 2009). Thus, caregivers’ self-efficacy during the pandemic may serve as protective factor, buffering the impact of COVID-19-related stress on family resilience.

The disruptions to daily life that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacted on families provide an opportunity to investigate the potential benefit of family routines during a period of global stress and uncertainty (i.e., a “natural experiment” setting). Using a national sample collected during May of 2020, the current study investigated the following aims. First, the study examined engagement in family routines prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we explored potential relations between family routines and demographic factors. We hypothesized that families would report engaging in fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, when compared to prior to the pandemic. We explored associations of family routines and demographic factors, including the age of child, number of children, socioeconomic status, and isolation status. Second, the study examined associations between caregiver’s internal resources (e.g., self-efficacy, stress mindset), COVID-19-related stress, engagement in family routines, and family resilience. We hypothesized that lower levels of self-efficacy and a debilitating stress mindset would be associated with higher levels of COVID-19-related stress, less engagement in family routines, and lower levels of family resilience. We hypothesized that higher levels of COVID-19-related stress would be associated with less engagement in family routines and lower levels of family resilience. Third, the study examined caregiver internal resources (i.e., stress mindset, self-efficacy) as moderators of relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. We hypothesized that high self-efficacy and an enhancing stress mindset would serve as a moderator (i.e., protective factor) of relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. Finally, the study examined engagement in family routines as a moderator of relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. We hypothesized that higher engagement in family routines would buffer associations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. Within moderation analyses, we accounted for the influence family routines and resilience prior to the COVID-19 pandemic to consider family routines and resilience within this unprecedented context.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The current cross-sectional study nationally surveyed 300 caregivers of at least one child between the ages 6 and 18 using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) for dissemination. MTurk is a widely used participant pool used by researchers to conduct large-scale studies and capture perspectives of individuals from diverse locations and backgrounds (e.g., Mason & Suri, 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013). Participants register through MTurk as “workers” to complete tasks for compensation. Relying on MTturk best practices in the assessment of caregivers (Schleider & Weisz, 2015), eligibility for the current study occurred at two levels (1) meeting requirements using MTurk’s built-in-settings and (2) meeting more detailed requirements assessed using a brief screener at the start of the survey. First, workers needed to (a) be from the U.S. and (b) have a 95% task approval rate based on their survey completion reputation (as recommended by Pe’er et al., 2014) to be marketed the current study on the MTurk platform. Second, as specified in our recruitment materials, workers were eligible for the survey if they (c) lived in the U.S., (d) were over 18 years old, and (e) lived with at least one child between the ages of 6-18 years. If workers did not meet the above criteria, Qualtrics immediately redirected them out of the survey during the screener. Workers were compensated $3.00 if they met all study criteria and completed at least 80% of the survey (as specified in the recruitment materials). Data collection started on May 1, 2020 and continued until 300 participants participated and met inclusion criteria (May 15, 2020). All procedures were approved by [Site Name]’s Institutional Review Board prior to beginning data collection.

Following data collection, several data quality checks were completed using questions embedded in the survey as well as assessing response patterns to ensure attentive and accurate responding (Schleider & Weisz, 2015; Hauser et al., 2018). First, participants were excluded from the analytic sample if they did not pass an attentional check at the end of the survey in the form of basic question (i.e., “Which of the following is not an animal? Horse, frog, shoe, tiger, butterfly”). Second, participants were excluded if they completed the survey in less than 10 min, as this was indicative of speeded responding. Third, participants were excluded if there was a mismatch in reported zip code, reported at the beginning of the survey, and U.S. state provided midway through the survey. After applying these data quality procedures, 245 participants were retained for the current analytic sample.

Participants (n = 245) included 42.4% females (Mage = 36.8 years, SD = 8.8 years). The majority of caregivers (89%) reported their marital status as married or currently cohabitating, with others reporting being never married (7%) or divorced (4%). Approximately 66.5% identified as White/Caucasian, 18.4% Black/African American, 10.2% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 2.4% Multiracial or Other Race (e.g., American Indian, Alaskan Native). Regarding education status, 55% of caregivers reported having obtained a Bachelor’s degree, 25% reported holding an advanced degree, 9% reported some college or training after high-school, 7% reported an associate’s or technical degree, and 4% reported a high-school education or GED. Approximately 18% and 33% of participants reported that they or a member of their household was a heath care provider or essential employee, respectively. Regarding employment status, 80% identified as working full time (40 or more hours per week), 8% identified as working part-time (up to 39 h per week), 6% identified as furloughed (still employed, but not currently being paid), 2% identified as a stay at home parent, 1% identified as a full-time student, 1% identified as unemployed, <1% identified as “Other.” Participants reports of household income (asked to report based on 2019 taxes) revealed that 34.7% reported household income less than $50,000, 29.8% reported income between $50,000 – 74,999 and 35.5% reported income above $75,000. Caregivers were from a wide range of states, though most (85%) reported zip codes in urban areas based on populations that exceeded 50,000 individuals (Ratcliffe et al., 2016). Additionally, caregivers reported on the number of people living in the home (range: 2–9 people, M = 3.1, SD = 1.2), not including themselves. Caregivers reported 1–6 children (M = 1.5, SD = 0.7) living in the home between the ages of 6–18 years old.

Measures

A series of measures were used to assess participants’ reports on variables related to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on personal and family functioning as well as engagement in family routines.

COVID-19 impact

Participants were asked several questions regarding the direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their household. Participants were asked about health care provider status; “Are you or anyone else in your household (e.g., partner, relative) a healthcare provider (e.g., nurse, physician, EMT)?” Participants were also asked, “Are you or anyone else in your household (e.g., partner, relative) an essential employee (e.g., able to go to work in spite of a shelter in place order. Examples include: mail carrier, plumber, pharmacist)?” Additionally, participants were asked if anyone in their household (including the participant) were suspected or diagnosed with COVID-19, and if so, the level of symptom severity (mild, moderate, or severe).

To assess isolation status, participants were asked, “What is your current isolation status? ‘Self-isolating’ was defined as staying at home and avoiding contact with people outside the household.” Participants were offered five response choices, ranging from, “none of the time, I am continuing my normal daily schedule,” to, “All or almost all of the time. I am staying home all or almost all of the time.” For analyses, responses were collapsed to compare individuals who were self-isolating “none” to “most of the time” to individuals who were self-isolating “all or almost all of the time.”

COVID-19-related stress

Levels of COVID-19-related stress were assessed with the 10-item Family Stress Screener (Huth-Bocks, 2020). Participants were prompted with the following statement “Because of COVID-19 related events and changes, I have felt increased stress about…” and asked to use a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to rate levels of stress regarding food security, job stability, finances, mental health, family conflict, and social isolation. Total scores were averaged to create a total score, in which higher scores indicate higher levels of COVID-19-related stress. This measure demonstrated excellent reliability (a = 0.90).

Individual wellbeing

Stress mindset. The Stress Mindset Measure (Crum et al., 2013) asks participants to respond to eight statements about how they experience stress (e.g., “the effects of stress are negative and should be avoided”) using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Responses to all eight items were averaged to create a total score, with higher scores indicating a view that stress is enhancing while lower scores indicate that stress is debilitating. Reliability of items within the total composite measure was acceptable (a = 0.68).

Self-efficacy. The four-item PROMIS General Self-Efficacy scale (Salsman et al., 2019) was used to assess participants’ level of confidence in managing different situations, problems, and events over the past two weeks. Responses options range from 1 (I am not at all confident) to 5 (I am very confident). Total scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater levels of self-efficacy. This scale demonstrated adequate reliability (a = 0.79).

Family routines

Family routines prior to COVID-19 and during COVID-19 were assessed using questions created for the current study. Questions were created based on a review of theoretical models of family routines and response to stress, including the Family Stress Model (Masarik & Conger, 2017), the theoretical model of family entropy (Bates et al., 2018; Bates et al., 2019), and Prime et al., 2020 model of family processes during the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature often describes family routines as activities that can be done between parent(s) and child(ren) to promote healthful routines or activities that requires parents imposing limits or restrictions to prevent unhealthful behaviors (e.g., snacking, screen time). Like previous measures (reviewed in Bates et al., 2018), the current study aimed to include information on sleeping, physical activity/inactivity (e.g., screen time), and eating (e.g., mealtimes, snacking). The authors also asked parents to report on limiting snacking during the day, particularly given the availability and accessibility of food in the context of self-isolation. Participants rated how often their family engaged in five different practices/routines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants used 1–5 scale (1 = never to 5 = every day) to respond to five statements, which included, “Child(ren) follow a bedtime routine (e.g., follows the same steps each night before bed),” and, “Parents set limits around our child(ren)’s screen time for non-school related work (e.g., limiting TV, computer, tablet, smartphone use.” Two subscales were created by calculating the means for (1) engagement in routines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) engagement in routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. This measure demonstrated good internal validity (prior to COVID-19 a = 0.78; during COVID-19 a = 0.82).

Family resilience

Family resilience was assessed using an adapted version of the Family Strengths/Resilience Questionnaire (Kumpfer et al., 2010). This 10-item measure asked participants to respond to the question, “How much strength would you say your family had prior to the COVID-19 outbreak (and now)?” by rating different areas (e.g., family supportiveness/love/care, physical health, positive family communication, social networking) on a scale of 1–5 (1 = none, 5 = very strong). Participants rated their family’s strengths and resilience prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Two subscales were created by calculating the means for (1) family strengths and resilience prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) family strengths and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reliability analyses indicated that this measure demonstrated excellent internal validity across reporting periods (prior to COVID-19 a = 0.86; during COVID-19 a = 0.87).

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means and standard deviations) were utilized to examine participant characteristics and key study variables. Twelve independent samples t-tests were run to explore whether COVID-19-related stress and engagement in family routines differed significantly based on participant demographic characteristics. Six paired-samples t-tests were conducted to assess change in family routines over time (i.e., prior to COVID-19 versus during the COVID-19 pandemic). Pearson correlations were utilized to examine relations between key study variables. Using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017), linear regressions were run to explore whether (1) caregiver internal resources moderated relations between COVID-19-related stress and family routines, and (2) family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic moderated relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuous variables to be tested as moderators were mean centered prior to being entered into the regression equation. Significant interaction terms (p < 0.05) were probed using tests of simple slopes. The total level of family routines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was entered into the second model as a covariate.

Results

COVID-19 Exposure and Stress

Participants reported a range of self-isolation at the time of survey completion (see Table 1). COVID-19-related stress was higher for those who indicated that they were self-isolating less than “all of the time,” in comparison to participants who reported self-isolating “all of the time” (t(243) = 2.08, p < 0.05). Additionally, COVID-19-related stress was significantly higher among certain demographic subgroups, including participants who reported a family income of less than $50,000 per year (t(243) = 2.01, p < 0.05), those who had been suspected of or received a diagnosis of COVID-19 (t(243) = 5.43, p < 0.001), and when someone in the household was a healthcare provider (t(236) = 2.95, p < 0.01). COVID-19-related stress did not differ significantly based on whether someone in the household was an essential employee outside of the healthcare profession or as a function of household size.

Table 1.

Participant response to question, “How much are you self-isolating?”

| Response | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| “None of the time. I am continuing my normal daily schedule.” | 12 (4.9) |

| “A small amount of the time. I have reduced some of the time that I am in public spaces, at social gatherings, church, and school.” | 32 (13.1) |

| “Some of the time. I have stopped going to work like normal and am social distancing from friends and family outside my home.” | 39 (15.9) |

| “Most of the time. I only leave for food, doctor appointments, and other essentials.” | 90 (36.7) |

| “All or almost all of the time. I am staying home all or almost all of the time.” | 72 (29.4) |

Family Routines and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Participants rated how frequently they engaged in various family routines, prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 2). Participants reported engaging in significantly fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to prior to the pandemic. At the item level, participants reported significantly reduced frequency of: (1) children following a bedtime routine (t(242) = 7.24, p < 0.001) and (2) parents setting screen time limits during the COVID-19 pandemic (t(240) = 3.77, p < 0.001). No significant changes were reported in the frequencies of family mealtimes or limits around snacking. Moreover, there were no differences in total engagement in family routines based on demographic variables, including income, size of family, isolation status, having been diagnosed with COVID-19, working in healthcare, or being an essential employee.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of items assessing family routines

| Item | Prior to COVID-19 M (SD) | During COVID-19 M (SD) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child(ren) follow a bedtime routine | 4.0 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.2) | 7.24*** |

| Family eats at least one meal together as a family | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | −0.23 |

| Parents set limits around the number of snacks that child(ren) eat(s) | 3.7 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.2) | 1.80 |

| Parents set limits around child(ren)’s screen time for non-school related work | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.2) | 3.77*** |

| “Parents play or do an activity with child(ren)” | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.1) | −1.72 |

| Total | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.55*** |

Note. Participants responded to each item using a 5-point Likert scale to report frequency of routines (1 = never to 5 = every day)

*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001

Relations between Family Routines, COVID-19-Related Stress, Internal Resources, and Family Resilience

Pearson correlations between main study variables are presented in Table 3. Higher engagement in family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with greater caregiver self-efficacy (r = 0.27, p < 0.001) and family resilience (during COVID-19 r = 0.51, p < 0.001). Greater COVID-19-related stress was associated with lower self-efficacy (r = −0.15, p < 0.05) and lower family resilience (during COVID-19 r = −0.27, p < 0.001). In addition, greater COVID-19-related stress was associated with higher levels of caregiver stress-mindset (r = 0.22, p < 0.01), indicating an enhancing view of stress. There was no significant association between COVID-19-related stress and family routines.

Table 3.

Descriptives and Pearson correlations among main study outcome variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family routines prior to COVID-19 | – | ||||||

| 2. Family routines during COVID-19 | 0.69*** | – | |||||

| 3. COVID-19-related stress | −0.09 | −0.07 | – | ||||

| 4. Stress mindset | −0.10 | −0.03 | 0.22*** | – | |||

| 5. Self-efficacy | 0.25*** | 0.27*** | −0.15* | −0.10 | – | ||

| 6. Family strengths & resilience prior to COVID-19 | 0.48*** | 0.41*** | −0.25*** | −0.21** | 0.46*** | – | |

| 7. Family strengths & resilience during COVID-19 | 0.42*** | 0.51*** | −0.27*** | −0.21** | 0.46*** | 0.77*** | – |

| M (SD) | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.7) | 3.9 (7.2) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.7) |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Moderating Influences

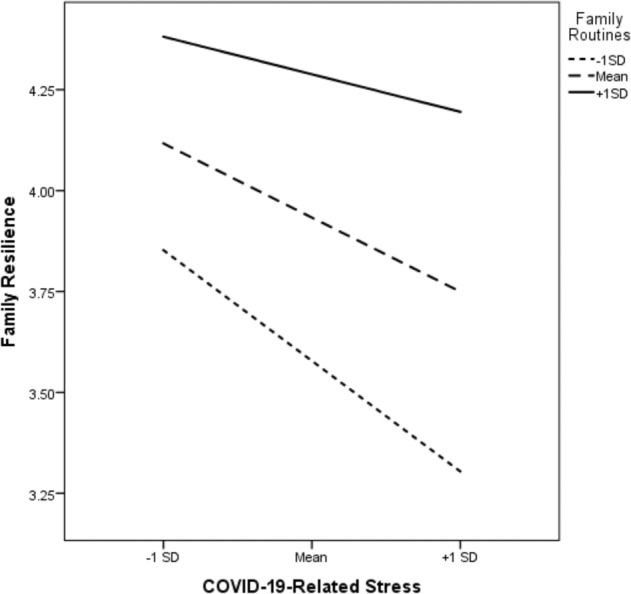

In linear regression analyses, neither stress mindset nor self-efficacy emerged as a significant moderator of the relations between COVID-19-related stress and family routines. However, there was a significant interaction between COVID-19-related stress and family routines on family resilience (B = 0.10, se = 0.04, p < 0.01), revealing that relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience were weakened if families were more engaged in routines (see Fig. 1). Specifically, COVID-19-related stress predicted lower levels of family resilience during COVID-19 among families who engaged in few routines (B = −0.28, se = 0.06, p < 0.001) or an “average” amount of routines based on the sample distribution (B = −0.19, se = 0.04, p < 0.001). For families who engaged in high-levels of family routines, COVID-19-related stress was not significantly associated with family resilience (B = −0.10, se = 0.05, p > 0.05). Findings remained significant even when accounting for the influence of family routines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Family routines moderate the impact of COVID-19-related stress on family resilience

Table 4.

Moderator analysis: family routines moderate relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Intercept | 4.13 | 0.46 | 3.22 | 5.04 | <0.001 |

| Family routines prior to COVID-19 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| COVID-19-related stress | −0.60 | 0.15 | −0.90 | −0.30 | <0.001 |

| Family routines during COVID-19 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.32 | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| Interactiona | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.004 |

| R2 | 0.34 | <0.001 | |||

N = 243

CI confidence interval, LL lower limit, UL upper limit

aInteraction between COVID-19-related stress and family routines

Given these findings, post-hoc simultaneous linear regression analyses were performed to examine relations between of discrete family routines and family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results revealed that three out of five family routines were significantly positively associated with family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, family resilience was positively associated with engagement in bedtime routines (β = 0.22, p < 0.01), family mealtimes (β = 0.22, p < 0.01), and screen time limits (β = 0.23, p < 0.01). Findings remained significant when accounting for levels of family routines prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Limits around snacking during the COVID-19 pandemic and parents playing or doing an activity with child(ren) were not significantly related to family resilience in any of the post-hoc regression models.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic required individuals across the US (and globally) to transition from attending work, education, and social gatherings, to staying home in order to prevent the spread of the virus. As a result, many activities that once took place outside of the home were abruptly eliminated or integrated into family context. Moreover, given limited contact with outside environments, the impact of the home environment became especially salient to well-being. The current study is among the first to empirically examine family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, including changes in routines, and relations to COVID-19-related stress, caregiver internal resources, and family resilience. In line with the theoretical model proposed by Prime et al., (2020), the study examined links between individual and family functioning during the pandemic. Key findings suggest that maintaining consistent family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic was challenging, and lower engagement in family routines was associated with poorer individual and family functioning. However, higher engagement in routines during the COVID-19 pandemic buffered relations between COVID-19-related stress and family functioning, and was also associated with improved internal resources within the parent. Positive associations between family routines and family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic occurred regardless of families’ prior engagement in family routines, suggesting acute and immediate benefit from these behaviors. Our results extend previous work that explores the mental and physical health benefits of family routines and add preliminary support for the benefits of routines during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Findings from the current study demonstrated that collectively, families engaged in fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to before the pandemic. Specifically, routines related to bedtime and limits around screen time were reduced. Reductions in family routines may in part be due to a reduction in social structures outside of the home (e.g., external work, school, and activity schedules; Brazendale et al., 2017), though it is notable that there were no significant differences in routines among families that included essential or health care workers, or based on isolation status. However, since nearly all states had enacted remote schooling orders at the time of the survey, it is possible that caregivers relaxed bedtime and screen time limits in accordance with more flexible school schedules for youth, regardless of parent work schedule. Moreover, as proposed by Prime et al., (2020), increasing demands of work, childcare, and schooling, all occurring within the family context, may tax caregivers’ ability to engage in other consistent parenting practices, such as setting limits around bedtime and screen time.

Reduced family routines, specifically bedtime and screen time routines, during COVID-19 may have negative implications for children’s health behaviors. It has been well-established that bedtime routines are an important component of sleep hygiene in children (Wilson et al., 2014). Additionally, screen time, particularly before bed, is associated with poor sleep duration and quality (Appelhans et al., 2014). Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent study examined differences in sleep disturbances, timing, and duration, in Chinese preschoolers while self-isolating at home during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a socio-demographically similar preschool sample from 2018 (prior to COVID-19). Findings demonstrated that preschoolers were sleeping later (>1 h) during COVID-19 than in 2018 (Liu et al., 2020). Another COVID-19 study of Canadian families of children between 5 and 11 years old found that children spent more time engaged in indoor play, sedentary behaviors, screen time, and social media during the COVID-19 pandemic, as compared to prior to the pandemic (Moore et al., 2020). However, both studies found that sleep duration increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Liu et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2020). Inconsistent sleep patterns and increased screen time have been associated with increased likelihood of developing obesity in children (e.g., Stiglic & Viner, 2019), and prior research suggests that low engagement in family routines may increase children’s risk for obesity (Hart et al., 2020). However, the long-term impact of changes in family routines and children’s health behaviors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic remains unknown.

The current study is one of the first to examine COVID-19-related stress. Results suggest that demographic factors played a role in families’ experience of stress related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, participants from lower income households (less than $50,000) reported greater COVID-19-related stress than those from higher income households. Indeed, families with fewer resources may have experienced more financial strain due to the economic disruption and upheaval during the COVID-19 pandemic. Greater COVID-19-related stress was reported among families of healthcare professionals, but not those of essential employees. Though both essential employees and healthcare workers may have continued to work outside the home, it is possible that increasing demands and known COVID-19 exposure in the healthcare setting contributed to higher COVID-19-related stress among families of healthcare providers. Interestingly, families who reported they were self-isolating “all the time” experienced less stress than families who reported leaving their home some of the time. Although prolonged isolation may have negative psychological effects (Brooks et al., 2020), we speculate that short-term self-isolation may have mitigated acute COVID-19-related stress by increasing perceived control around virus exposure and risk.

Contrary to hypotheses, engagement in family routines was independent of COVID-19-related stress. Moreover, moderation analyses did not reveal any relation between COVID-19-related stress and family routines based on caregivers’ internal resources (e.g., high or low self-efficacy, stress mindset). Though unexpected, this finding demonstrates that it was possible for families to engage in consistent routines despite stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may serve as a promising foundation for interventions to promote caregiver, child, and family well-being. Indeed, engagement in family routines was associated with many positive outcomes, including higher caregiver self-efficacy and family resilience. Notably, causation cannot be inferred due to the correlational nature of the study. High levels of COVID-19-related stress were associated with lower caregiver self-efficacy, and lower family resilience, suggesting a deleterious association between acute pandemic stress, internal resources, and family functioning. On the other hand, COVID-19-related stress was unexpectedly related to a more “enhancing” stress mindset. This finding highlights the stress paradox (Crum et al., 2013), in which stress can have both debilitating and beneficial impact on individuals. Acknowledging the many challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible that stress related to the pandemic may have brought about some positive outcomes for health and vitality (e.g., deeper family relationships, greater appreciation for life), learning and growth (e.g., new perspectives, mental toughness), or performance and productivity (e.g., strengthened priorities, improved focus on tasks at hand; Crum et al., 2013). The nature of the stress paradox in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic warrants further exploration to identify not only areas of risk, but also areas of stress-related growth (Park & Helgeson, 2006) and implications during this unprecedented period in time.

Finally, a major discovery from this study is that family routines moderated relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience. Specifically, while COVID-19-related stress was negatively associated with family resilience at low and moderate levels of engagement in family routines, relations between COVID-19-related stress and family resilience were non-significant when families engaged in high levels of routines. However, greater COVID-19-related stress was associated with lower family resilience when families engaged in fewer or less frequent routines. Post-hoc analyses suggested that family mealtimes and limits around screen time may have been particularly relevant to family resilience during the pandemic. Previous work has suggested that engaging in more family routines may better equip families to efficiently adapt to and function during times of high stress (Harrist et al., 2019). Indeed, families benefitted from high levels of routines during the COVID-19 pandemic regardless of their previous engagement in family routines, suggesting acute and immediate benefits of these positive practices. Family routines have been shown to be protective to adults and children in the context of numerous acute and chronic stressors, including chronic illnesses, neighborhood stress, post-traumatic stress, etc. (Bocknek et al., 2017; Denny et al., 2012; Kiser et al., 2010). During times of stress and uncertainty, routines establish control and predictability, and promote comforting, consistent interactions between children and their caregivers (Harrist et al., 2019). In unfamiliar, unpredictable circumstances, especially those with new responsibilities, the prefrontal cortex is severely taxed (Arnsten, 2009). Amidst the uncertainty and novel demands of the COVID-19 pandemic, family routines—particularly those that limit additional distraction (e.g., screen time) and promote positive interactions (e.g., mealtimes)—may relieve demands on the executive functioning system by promoting familiar, stable interactions, that provide stress relief and enhance resilience.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study utilized a national, online survey for wide dissemination during a time-sensitive window of the COVID-19 pandemic. The remote and online nature of data collection, while advantageous during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, limited the study team’s ability to ensure participant understanding of study questions and to completely rule out any speeded responding. We relied on published protocols to maximize data integrity within the sample strategy (Schleider & Weisz, 2015). The study is also limited by a cross-sectional methodology, which precludes causal interpretations of data. All data is self-reported and therefore subject to sampling and response bias. The number of t-tests run increases the probability of Type 1 error, and thus replication studies would be useful to confirm findings. Finally, it was necessary to develop methodologies to assess novel constructs, including COVID-19-related stress and changes in family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The development of these measures was grounded in theory, but measures have not been validated in a larger sample. Relatedly, aspects of our measures may not fully capture the changing landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic, heralding the need for more research in this area. For example, our self-isolation measure captured physical distancing and did assess for virtual social engagement that may also buffer the effects of stress during the pandemic. Additionally, there is a need to capture stress that may arise related to childcare decisions, particularly for healthcare providers and essential employees.

Acknowledging limitations, this study is nevertheless an initial, foundational examination of family routines, stress, and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study builds on existing literature that has established the benefits of social and behavioral routines to family and child health and resilience, and supports the benefits of engaging in family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are numerous future directions for this work. Larger, longitudinal studies are needed to assess changes in family functioning, stress, and outcomes over time during the COVID-19 pandemic, and impact on caregiver and child wellbeing. Validation studies are needed for new measures that were utilized to assess the acute and long-term impact of COVID-19 on stress and family outcomes. This study additionally lays a foundation for interventions that examine the role of family routines in promoting or improving stress management, health, and resilience among caregivers and children during periods of stress and disruption.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to explore family routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Families engaged in fewer routines during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic, supporting the challenges of maintaining regular family functioning during this public health crisis. However, engagement in family routines exerted a protective effect on family resilience and caregiver well-being. Family routines are low-cost, widely disseminable behaviors that may have a powerful impact on caregiver, child, and family well-being. Greater awareness, understanding, and support for policies and interventions that promote the maintenance of protective family practices may facilitate greater individual, family, and societal resilience during periods of acute health, economic, and social stress.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures in the current study were approved by the home University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Informed Consent

All participants completed informed consent documentation as approved by the IRB.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Appelhans BM, Fitzpatrick SL, Li H, Cail V, Waring ME, Schneider KL, Pagoto SL. The home environment and childhood obesity in low-income households: indirect effects via sleep duration and screen time. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(6):410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

- Bates CR, Buscemi J, Nicholson LM, Cory M, Jagpal A, Bohnert AM. Links between the organization of the family home environment and child obesity: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2018;19(5):716–727. doi: 10.1111/obr.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates CR, Bohnert AM, Buscemi J, Vandell DL, Lee KT, Bryant FB. Family entropy: understanding the organization of the family home environment and impact on child health behaviors and weight. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2019;9(3):413–421. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzies K, Mychasiuk R. Fostering family resiliency: A review of the key protective factors. Child & Family Social Work. 2009;14(1):103–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bocknek EL, Dayton C, Raveau HA, Richardson P, Brophy-Herb HE, Fitzgerald HE. Routine active playtime with fathers is associated with self-regulation in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2017;63(1):105–134. doi: 10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.63.1.0105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG, Pate RR, Turner-McGrievy GM, Kaczynski AT, von Hippel PT. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: the structured days hypothesis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Salovey P, Achor S. Rethinking stress: the role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104(4):716–733. doi: 10.1037/a0031201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Akinola M, Martin A, Fath S. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2017;30(4):379–395. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.1275585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daks JS, Peltz JS, Rogge RD. Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020;18:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obesity Reviews. 2001;2(3):159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny B, Beyerle K, Kienhuis M, Cora A, Gavidia-Payne S, Hardikar W. New insights into family functioning and quality of life after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatric Transplantation. 2012;16(7):711–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Education Week. (2020). Map: Coronavirus and school closures 2019-2020. https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/map-coronavirus-and-school-closures.html.

- Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(4):381–390. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese, B. H. (2006). Family routines and rituals. Yale University Press.

- Glynn LM, Davis EP, Luby JL, Baram TZ, Sandman CA. A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiology of Stress. 2021;14:100291. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrist, A. W., Henry, C. S., Liu, C., & Morris, A. S. (2019). Family resilience: The power of rituals and routines in family adaptive systems. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (p. 223–239). American Psychological Association.

- Hart CN, Jelalian E, Raynor HA. Behavioral and social routines and biological rhythms in prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity. American Psychologist. 2020;75(2):152–162. doi: 10.1037/amp0000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, D., Paolacci, G., & Chandler, J. J. (2018). Common concerns with MTurk as a participant pool: evidence and solutions. In Kardes, F., Herr, P., & Schwarz, N (Eds). Handbook in Research Methods in Consumer Psychology. 10.31234/osf.io/uq45c.

- Hawley DR, DeHaan L. Toward a definition of family resilience: integrating life-span and family perspectives. Family Process. 1996;35:283–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Henry CS, Sheffield Morris A, Harrist AW. Family resilience: moving into the third wave. Family Relations. 2015;64(1):22–43. doi: 10.1111/fare.12106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huth-Bocks, A. (2020). COVID-19 Family Stress Screener. SRCD Commons. https://commons.srcd.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=4d647e65-0459-4c72-a051-c671d42eb9ab.

- Jensen EW, James SA, Boyce WT, Hartnett SA. The family routines inventory: development and validation. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 1983;17(4):201–211. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser LJ, Medoff DR, Black MM. The role of family processes in childhood traumatic stress reactions for youths living in urban poverty. Traumatology. 2010;16(2):33–42. doi: 10.1177/1534765609358466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Whiteside HO, Greene JA, Allen KC. Effectiveness outcomes of four age versions of the Strengthening Families Program in statewide field sites. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2010;14(3):211. doi: 10.1037/a0020602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., Tang, H., Jin, Q., Wang, G., Yang, Z., Chen, H., & Owens, J. (2020). Sleep of preschoolers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Journal of Sleep Research, e13142. 10.1111/jsr.13142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Luszczynska A, Benight CC, Cieslak R. Self-efficacy and health-related outcomes of collective trauma: a systematic review. European Psychologist. 2009;14(1):51–62. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Hiscock H, Hardy P, Davey B, Wake M. Adverse associations of infant and child sleep problems and parent health: an Australian population study. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):947–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masarik AS, Conger RD. Stress and child development: a review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;13:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods. 2012;44(1):1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Lumeng JC, LeBourgeois MK. Sleep patterns and obesity in childhood. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity. 2015;22(1):41–47. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Faulkner G, Rhodes RE, Brussoni M, Chulak-Bozzer T, Ferguson LJ, Tremblay MS. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2020;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NBC News. (2020). Stay at home orders across the country. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/here-are-stay-home-orders-across-country-n1168736.

- Park CL, Helgeson VS. Introduction to the special section: growth following highly stressful life events—current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):791–796. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er E, Vosgerau J, Acquisti A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods. 2014;46(4):1023–1031. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0434-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.pewresearch.org/topics/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/.

- Prime H, Wade M, Browne DT. Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist. 2020;75(5):631–643. doi: 10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. Defining rural at the US Census Bureau. American Community Survey and Geography Brief. 2016;1(8):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman JM, Schalet BD, Merluzzi TV, Park CL, Hahn EA, Snyder MA, Cella D. Calibration and initial validation of a general self-efficacy item bank and short form for the NIH PROMIS®. Quality of Life Research. 2019;28(9):2513–2523. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02198-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Using Mechanical Turk to study family processes and youth mental health: a test of feasibility. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(11):3235–3246. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0126-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DN, Chandler J, Mueller PA. Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013;1(2):213–220. doi: 10.1177/2167702612469015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stiglic N, Viner RM. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):1–15. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso, W. W. Y., Wong, R. S., Tung, K. T. S., Rao, N., Fu, K. W., Yam, J. C. S., Chua, G. T., Chen, E. Y. H., Lee, T. M. C., Chan, S. K. W., Wong, W. H. S., Xiong, X., Chui, C. S., Li, X., Wong, K., Leung, C., Tsang, S. K. M., Chan, G. C. F., Tam, P. K. H., … lp, P. (2020). Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1007/s00787-020-01680-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Utter J, Larson N, Berge JM, Eisenberg ME, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family meals among parents: associations with nutritional, social and emotional wellbeing. Preventive Medicine. 2018;113:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Moreno, S., Lacomba-Trejo, L., Tamarit, A., Pérez-Marín, M., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2021). Psycho-emotional adjustment in parents of adolescents: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of the impact of the COVID pandemic. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, S0882596321000312. 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wilson KE, Miller AL, Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Sleep environments and sleep durations in a sample of low-income preschool children. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014;10(3):299–305. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]