Abstract

Introduction and importance

Stenosis of the colostomy occurs in 2–15% of patients and, they are the cause of serious discomfort for the patient due to the difficulty in evacuation, as well as the need for new surgical interventions. The purpose of this work demonstrates an outpatient surgical treatment that can be performed in the office.

Case presentation

Three patients with definitive colostomy who suffered progressive stenosis are presented. Under local anesthesia, one or two triangular segments, with their bases on the colostomy, which included the thickened and hardened skin, are removed to expand the diameter of the stoma. The mucosa of the colon is sutured to healthy skin with Vicryl 3/0 simple stitches.

This method has been used in three patients older than 60 years with permanent colostomy who presented with progressive stenosis 6–7 months after surgery. The average follow-up at 14.5 months was satisfactory, without restenosis.

Discussion

Stoma stenosis is a complication that occurs in up to 15% of cases and requires reconstruction, most of which are carried out in the operating room.

The triangular stenoplasty presented is effective and is performed under local anesthesia in the office.

Conclusion

Triangular-section stenoplasty of a stenosed permanent colostomy is an effective outpatient treatment.

Keywords: Colostomy; Stoma, stenosis, complication, case report

Highlights

-

•

Colostomy is still a common procedure in emergency colon surgery.

-

•

Complications of a colostomy range from 15% to 70%

-

•

Stenosis of a colostomy occurs in up to 15% of cases.

-

•

The triangular stenoplasty of colostomy under local anesthesia, is efficient and with satisfactory long-term results

1. Introduction

Diversion of the colon to the abdominal wall through a stoma is a frequent surgical procedure that is performed for various inflammatory, neoplastic, and traumatic pathologies in case of anastomotic leaks and fistulas to other organs or perianal lesions. This colostomy can be temporary or permanent and end (single stoma) or double barrel (proximal and distal stoma).

The early complications of a stoma of the colon include necrosis, narrowing of the stoma, and detachment, which can be complicated by leakage of the colonic content into the abdominal cavity or infection of the soft parts of the abdominal wall, and these can evolve into necrotizing fasciitis; the late complications are periostomal dermatitis, stoma retraction, prolapse, parastomal hernia, and stenosis [1], [2].

Risk factors for stoma complications include obesity, chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, smoking, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignant colon disease, which can be associated with inadequate surgical techniques in colostomy construction and when performed as emergency surgery [3].

Stenosis of the colostomy, which in this article we will refer to as those that form late and not to the immediate postoperative narrowing that is due to inflammation of the area, occurs in 2–15% of patients and is mainly due to ischemia, the process of skin scarring, or nonspecific inflammatory disease of the colon or residual neoplasia in the stoma [2]. According to Paquette [3], a frequent condition associated with stoma stenosis is early mucocutaneous separation and retraction due to the effects of healing and secondary wound contracture.

Among the recommended treatments for end colostomy stenosis are mild serial dilatations and the creation of a new stoma.

To reduce the risks of complications, a refined surgical technique is put forth. It includes adequate irrigation of the end stoma, no tension in the derived loop, opening of the skin appropriate to the size of the stoma of the colon, and the mucosa exceeding at least 1.5 cm from the skin [1], [2], [3].

The purpose of this work demonstrates that a triangular stenoplasty can be performed in the office. The patients were managed in private practice setting.

2. Presentation of cases

We present the experience of ambulatory surgical management through triangular stenoplasty in three patients with permanent end colostomy with progressive stenosis. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the patients, their concomitant diseases, the indication for colostomy, and their evolution. These patients, when undergoing emergency surgery, did not have the appropriate stoma site marked, and all three received follow-up and care by specialist stoma therapists.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with terminal and permanent colostomy.

| Patient 1a | Patient 2 | Patient 3a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Male | Female |

| Age | 62 | 48 | 68 |

| Concomitant diseases | Diabetes mellitus | None | Obesity |

| Indication of colostomy | Complicated diverticular disease with abscess | Stenosing advanced adenocarcinoma of the rectum | Complicated diverticular disease with fecal peritonitis |

| Type of surgery | Emergency | Emergency | Emergency |

| Postoperative | Retraction of the stoma (without detachment) | Received radio- and chemotherapy | No apparent alteration |

| Beginning of stenosis management | 30 days | 45 days | 20 days |

| Moment of stenoplasty | 6 months | 5 months | 7 months |

| Follow-up | 18 months | 14 months | 12 months |

| Evolution | Satisfactory | Satisfactory | Satisfactory |

Patients 1 and 3 did not consent to reconnection of the colon.

3. Method of repair

With the consent of the patient, under local periostomal anesthesia with Lidocaine 0.5%, the most appropriate sites are identified for the removal of one or two triangular segments, whose bases are on the colostomy and which include thickened and hard skin, usually with active scarring up to the limit of the mucosa of the stoma (Fig. 1). If there is bleeding from the skin and fatty tissue, this is controlled with simple suture or electrocautery. The stoma mucosa was identified and sutured to healthy skin with Vicryl 3/0 simple stitches.

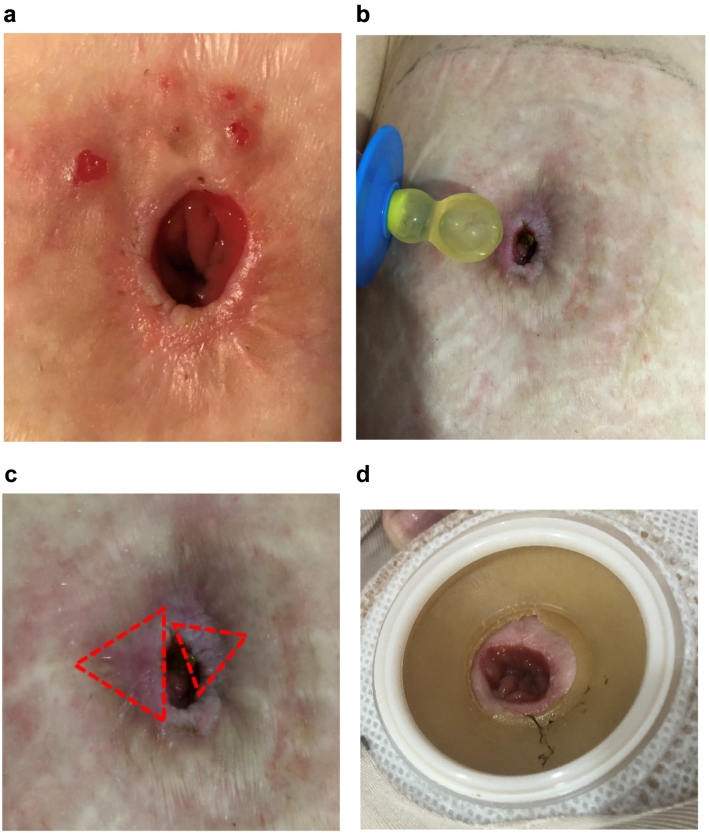

Fig. 1.

a. Colostomy of patient 3 at 60 days after surgery. Note the retraction of the mucosa and the thickening of the skin around it (active scarring).

b. Same colostomy at 6 months, with stenosis.

c. Triangular cut sites to expand the diameter of the stenosed colostomy skin.

d. Colostomy one month after triangular stenoplasty.

500 mg of oral paracetamol was indicated for the control of postoperative pain, if necessary.

The procedure was carried out by the article's author, Dr. Gilberto Guzmán-Valdivia, a general surgeon with 30 years of experience in digestive tract surgery.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [4].

4. Results

Triangular stenoplasty was performed in three patients with progressive stenosis of their definitive stoma. In an average follow-up period of 14.5 months (12, 14 and 18 months respectively) per monthly medical visit, the colostomy was functional without restenosis of the stoma. The patients were very satisfied with the results obtained by the procedure.

5. Discussion

The decision to make a colostomy is frequent in colon surgery. Remember that many of these patients could be treated with primary anastomosis, although the Hartmann procedure is still frequently performed in patients with purulent or fecal peritonitis or with hemodynamic instability, mainly in emergency surgeries. Additionally, in up to 25% of cases, the patient decides not to close their stomata because the experience of recovering from their surgery was traumatic [5].

Complications of a stoma have been reported in 21 to 70% of cases, mainly necrosis, retraction, prolapse, dermatitis, parastomal hernia, and stenosis, the latter in 2 to 15% of cases [1], [2]. Stenosis occurs mainly from the second week to 5 years after the procedure [2]. The most frequent risk factors for stenosis are inadequate colon mobilization, secondary ischemia and insufficient opening of the abdominal wall and skin. In the three cases presented, stenosis occurred between 20 and 45 days after surgery with progressive worsening until they were forced to seek radical treatment.

Both the patient and surgeon observe how the stoma is stenosing over time. The management begins with the modification of the diet to make the feces softer since there is difficulty in evacuating the feces, and their flatus even becomes louder; complete obstruction is rare because the stenosis is treated before this happens [6], [7].

For permanent stomas that are stenotic, the proposed treatments include periodic dilation with different instruments, including Hegar dilators, but the results have not been entirely satisfactory [2]. We proposed the daily placement of a baby pacifier to our patients, but the stenosis worsened. If the colostomy is temporary, then the reversal of the stoma with colonic anastomosis is chosen, but when the stoma is permanent, there is a need to perform colostomy again as a formal surgical procedure in the operating room, either manually or with a circular stapler [8], [9].

In the three patients presented, who underwent triangular stenoplasty under local anesthesia and in the office, the evolution at 12, 14, and 18 months was satisfactory since the active skin was removed in the healing process as the diameter of the stoma expanded. The author chooses this technique rather than other techniques because it is simple, it is well tolerated and that it can be performed in the doctor's office with little risk.

Dr. Ian Paquette [3] recommends that, in both elective and emergency surgeries, the stoma site should be planned, although in obese patients, due to the short conditions of the mesentery and the thickness of the abdominal wall, the choice of site is made at the time of surgery. The same applies to patients with acute abdomen due to abscesses and peritonitis. Ideally, the segment of the derived colon lacks tension and is well vascularized; however, in inflammatory bowel disease and diverticular disease of the colon, the segment prepared for the stoma is often inflamed and can become ischemic.

The three patients who presented gave their informed consent for the publication of their intervention.

6. Conclusion

Stenoplasty with one or two triangular cuts with their bases on stenotic colostomy is an option for the outpatient treatment of colostomy stenosis.

Ethics approval

The three patients signed an informed consent, knowing that the outpatient treatment of their colostomy stenosis is a novel procedure and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Mexican School of Medicine of La Salle University with number CEI 2019/15.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from founding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

The author's contribution was the design and operation of the surgical procedure, as well as the preparation and approval of the manuscript.

Guarantor

Dr. María Guadalupe Castro Martínez

Director of the Mexican School of Medicine at La Salle University, Mexico

Guadalupe.castro@lasalle.mx

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Murken D.R., Bleier J.I.S. Ostomy-related complications. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:176–182. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shabbir J., Britton D.C. Stoma complications: a literature overview. Color. Dis. 2010;12:958–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paquette I.M. Expert commentary on the prevention and management of colostomy complications: retraction and stenosis. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1348–1349. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.for the SCARE Group. Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrabi C., Mathew G. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzmán-Valdivia G. Incisional hernia at the site of a stoma. Hernia. 2008;12(5):471–474. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Flynn S.K. Care of the stoma: complications and treatments. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2018;23:382–387. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2018.23.8.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuczynska B., Bobkiewicz A., Studniarek A. Conservative measures for managing constipation in patients living with a colostomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44:160–164. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imagami T., Takayama S., Maeda Y., Hattori T., Matsui R., Sakamoto M. Surgical resection of anastomotic stenosis after rectal cancer surgery using a circular stapler and colostomy with double orifice. Case Rep. Surg. 2019;19:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2019/2898691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skokowski J., Bobowicz M., Kalinowska A. Extracorporeal staple technique: an alternative approach to the treatment of critical colostomy stenosis. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2015;10:316–319. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2015.52474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]