Abstract

This study estimates random effects and difference-in-difference-in-differences models to examine the initial impacts of COVID-19 on the employment and hours of unincorporated self-employed workers using monthly panel data from the Current Population Survey. For these workers, effects were visible in March as voluntary social distancing began, largest in April as complete shutdowns occurred, and slightly smaller in May as some restrictions were eased. We find differential effects by gender that favor men, by marital status and gender that favor married men over married women, and by gender, marital, and parental status that favor married fathers over married mothers. The evidence suggests that self-employed married mothers were forced out of the labor force to care for children presumably due to prescribed gender norms and the division and specialization of labor within households. Remote work and working in an essential industry mitigated some of the negative effects on employment and hours.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hours worked, Self-employment, Entrepreneurship, Gender, Remote work

Plain language summary

Among the unincorporated self-employed, married mothers were less likely to be employed and worked fewer hours during the COVID-19 pandemic than married fathers. Effects were visible in March as voluntary social distancing began, largest in April as complete shutdowns occurred, and slightly smaller in May as some restrictions were eased. Our results suggest that COVID-19 forced self-employed women back into the home due to gender norms about who cares for children. However, having a plausibly remote job or being in an essential industry helped mitigate some of the negative effects on employment and hours worked. Besides providing evidence that married mothers’ presence among the self-employed has been diminished by COVID-19, we find that the pandemic hurt the unincorporated self-employed more than other types of workers. This finding provides further evidence that it is important for researchers to distinguish between the incorporated and unincorporated self-employed when analyzing variation in self-employment at different points in the business cycle.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to serious disruptions in work, schooling, and family life in the USA and around the world, though not all have been affected equally. Initially, in late February and early March 2020, individuals in the USA voluntarily started restricting activities to avoid exposure as news of the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread and some counties closed their schools (Goolsbee & Syverson, 2021; Heggeness, 2020). Then, in the second half of March 2020, many state and local governments began to impose stay-at-home orders and online schooling and mandate closures of “nonessential” businesses, resulting in further restrictions of movement by individuals. Other states imposed partial business closures. The most restrictions and school closures were in effect in April of 2020. In May, some governments began easing restrictions, but most schools remained closed until the end of the school year.

This paper focuses primarily on the early effects of the pandemic on the unincorporated self-employed.1 Self-employed workers are those who run businesses that organize factors of production to sell goods or services or those who sell their labor services as independent contractors, day laborers, or gig workers (Abraham et al., 2020). They create jobs for themselves and often others, making up about 10% of all employment in the economy (Hipple & Hammond, 2016). Some of these businesses are incorporated but the majority are unincorporated. Official U.S. estimates of self-employment are based upon the unincorporated self-employed because the incorporated self-employed are classified as employees of their own businesses.

Levine and Rubinstein (2017) note that incorporating a business allows the business owners to benefit from limited liability and a separate legal identity that protects those seeking to undertake risky investments, but at a cost, including the costs of incorporation, annual fees, and preparing financial statements. Using data from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Dictionary of Occupational Titles, the Current Population Survey (CPS), and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, they also show that incorporated and unincorporated self-employed workers perform much different activities. On average, the incorporated perform activities requiring relatively stronger nonroutine cognitive skills, while the unincorporated perform activities requiring relatively lower levels of cognitive skills and relatively stronger manual skills. Overall, the incorporated self-employed are also more growth-oriented, committed, and entrepreneurial than the unincorporated self-employed (Fairlie & Miranda, 2017; Fairlie et al., 2019). The unincorporated self-employed are more likely to be nonemployers. Analyzing data from the Kauffman Firm Surveys for the Small Business Administration, Cole (2011) found that the self-employed choose a complex form of legalization when they employ more people or have more assets, when they use a business credit card for financing, and when the primary owner is more educated. There is substantial evidence that, once established, businesses rarely change their legal form of organization (Cole, 2011; Fairlie & Miranda, 2017; Levine & Rubinstein, 2017). Fossen (2020) and Fairlie (2020) have shown that it is important to distinguish between the incorporated and unincorporated self-employed when examining variation in self-employment over the business cycle.

For several reasons, the unincorporated self-employed may have experienced the early months of this pandemic recession differently from the incorporated self-employed and other wage and salary workers, especially the female unincorporated self-employed. First, the pandemic had a larger effect on the service sector than the goods sector, because face-to-face interaction is more prevalent in the service sector (Alon et al., 2020a, b). Among female workers in February 2020, 91% of the unincorporated self-employed worked in the service sector, while 86% of wage and salary workers worked in the service sector. On the other hand, among male workers, only 60% of the unincorporated self-employed worked in the service sector, while 67% of wage and salary workers worked in the service sector.2

Second, the unincorporated self-employed traditionally have not been eligible for social insurance programs such as unemployment insurance. Incorporated self-employed workers who own a corporation or an “S” corporation and pay themselves a W-2 wage are eligible for traditional UI benefits. Unincorporated self-employed workers are not. However, while the CARES Act, enacted on March 27, 2020, allocated federal funds to states to use for the self-employed under a program called the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, it was unclear which self-employed workers were eligible, and many did not apply. In addition, states varied in their ability to orchestrate this new program in a timely manner. Some states started to pay out in late April 2020. However, as of May 12, only 37 of the 50 states had started to make payments, and many eligible workers were still waiting for checks (Bahler, 2020). Another pandemic assistance program was the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) that on April 3rd started allocating to small businesses with a payroll loans that could be forgiven under certain conditions. However, demand for loans was high, and the initial PPP program funds were depleted by April 16. Congress then appropriated funds for additional loans through the PPP Act, and banks started to issue additional PPP loans on April 27. Doniger and Kay (2021) find that this 10-day delay in financing led to significant job losses in May, especially among the self-employed. Although these loans were targeted for small businesses through the Small Business Administration, the largest of the small businesses were more likely to receive PPP loans in the early stages of the program than the unincorporated self-employed, as they tend to have smaller businesses and are more likely to be nonemployers, especially among the female self-employed (Balyuk et al., 2020; Cole, 2011; Doniger & Kay, 2021; Fairlie & Miranda, 2017; Humphries et al., 2020). Thus, differences in the social safety net may have affected the unincorporated self-employed and the incorporated self-employed differently.

Third, the ability of many Americans to work from home has dampened the resulting economic crisis (Barrero et al., 2020; Bick et al., 2021; Brynjolfsson et al., 2020; Montenovo et al., 2020). According to the 2018 American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which showed time use 1 to 2 years pre-pandemic, 51% of unincorporated self-employed workers in the USA did some work from home on their primary job on an average day, while only 21% of wage and salary workers did so (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). Thus, the unincorporated self-employed also may have been more likely to do some of their work from home during the pandemic than wage and salary workers.

Finally, self-employed workers who were able to work from home were at the same time affected by school and daycare shutdowns, with children now being thrust into their work environment. These shutdowns may have affected female self-employed parents more than male self-employed parents because of gender norms within the home that result in women doing much of the child care (Burda et al., 2008; Sent & van Staveren, 2019; Sevilla & Smith, 2020). However, women are more likely than men to become self-employed to better balance work and family demands (Budig, 2006; Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2012; Lim, 2019) and so may have been able to weather the shutdowns better. Given these issues, there may have been differential impacts on the self-employed by gender, marital status, and parental status.

We examine the early impacts of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic on the employment and hours of work of unincorporated self-employed workers. On the supply side, some workers left employment or reduced their hours of work because of their own or their customers’ fear of contracting the novel coronavirus or because they needed to take care of and educate their children at home. On the demand side, government shutdowns of businesses and the implementation of other restrictions related to “essential” business designations reduced the demand for workers and worker hours. Our analysis examines the effects of COVID-19, controlling for factors such as the presence of children, marital status, remote job, and essential-worker status, but cannot completely disentangle these supply and demand effects. We use monthly panel data from the CPS for those who were self-employed and at work in February 2020 to trace the effects from February through May of 2020, and both random-effects (RE) and difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) models. Data from February and April 2019 also are used for the DDD models to create the control group (Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau, 2019–2020). We also compare the effects of COVID-19 on employees and incorporated self-employed workers to show that those workers classified as unincorporated self-employed in February 2020 on their primary job were disproportionately affected by COVID-19.3

In the analyses, February 2020 is considered a normal month, and March, April, and May of 2020 are months affected by COVID-19. Social distancing policies and shutdowns of schools and businesses began in March, were widespread by April, and began being relaxed in some locations in May. The school closures for primary and secondary students occurred for the most part after the March CPS reference week. All states had adopted some form of social distancing measures by March 23 (Adolph et al., 2020). Given the sequence of events, the negative effects of the shutdowns should be larger in April than in March and smaller in May than in April.

We find that the pandemic decreased employment and hours for all groups of workers, with the unincorporated self-employed being hit the hardest. Reductions in employment and hours were larger for April than for March compared to February, and the loosening of restrictions in May did not yet have much of a moderating effect. Among the unincorporated self-employed workers, we find differential effects of COVID-19 by gender that favor men, by marital status and gender that favor married men over married women, and by gender, marital status, and parental status that favor married fathers over married mothers.4 Females fared worse than males in terms of reductions in employment and hours of work, perhaps because of supply shocks as more risk-averse women left employment than men or because demand shocks were higher in female-dominated jobs. Married women were especially worse off compared to married men, and married mothers especially worse off compared to married fathers. Thus, in addition to these demand and supply shocks, the evidence suggests that married mothers have been forced out of the labor force to care for children presumably due to prescribed gender norms and the division and specialization of labor within households. Having a plausibly remote job and working in an essential industry mitigated some of these effects. Thus, COVID-19 has erased much of self-employed women’s hard-earned gains in the labor market.

Related literature

Self-employment literature

The unincorporated self-employed have unique characteristics. Compared to the incorporated self-employed, they tend to engage in work activities that demand relatively low levels of cognitive skills and high levels of manual coordination (Levine & Rubinstein, 2017). Although many of the unincorporated self-employed may do some work from home, a significant portion work in construction, including small, home-construction activities whose services were in lower demand during the early stages of the pandemic while households were social distancing (Hipple & Hammond, 2016). Some choose self-employment, even as a primary job, to work part-time or on an intermittent basis as an independent contractor or consultant to better balance work and life activities (Abraham & Houseman, 2019). Because they can control their work hours to a greater extent than wage and salary workers, self-employed parents may have more flexibility to work reduced hours rather than stopping work altogether to provide child care.

Prior research on the effects of macroeconomic conditions on the unincorporated self-employed in the USA finds that their total hours are procyclical (Carrington et al., 1996; Pabilonia, 2014); however, higher unemployment rates are associated with an increase in entry rates into self-employment, often due to a lack of alternatives (Fairlie, 2013; Fairlie & Fossen, 2020), even at potentially reduced hours. Fairlie (2020) uses the CPS microdata to examine the early effects of COVID-19 on U.S. business owners (many of whom are classified as unincorporated self-employed workers). He finds that the number of actively working unincorporated business owners dropped by 28% between February and April of 2020, while the number of incorporated business owners dropped by only 14%. In addition, African-American, immigrant, and female business owners were especially hard hit by the shutdown of nonessential activities. Using simulations, he finds that part of this decline in female-owned businesses is because of differences in the industry distribution of businesses owned by gender. In May and June of 2020, he shows that small businesses sustained continued losses but also experienced a partial rebound as restrictions were eased. Over the same period, but for Canadian self-employed workers, Beland et al. (2020) find smaller decreases between February and May in the number of unincorporated businesses compared to the number of incorporated businesses (10% versus 15%). They also find a substantial disproportionate decrease in ownership and aggregate hours for women, immigrants, and less-educated people. These reductions in female-owned businesses may lead to additional problems beyond the owner’s loss of work, however. Studying the Great Recession, Matsa and Miller (2014) found that female business owners were less likely to lay off their employees than male business owners, while Deller et al. (2017) found that regions of the USA with a greater share of female-owned businesses had greater regional employment-related stability.

Gender and intra-household allocation literature

In married households, members of a couple jointly decide how much time to devote to market work, household production, and child care, and, according to standard household economic theories, time spent in these different activities depends on relative income, social norms, productivity differences in time inputs, and bargaining power (Becker, 1965, 1973, 1974; Lundberg & Pollak, 1994; Manser & Brown, 1980; McElroy & Horney, 1981; Schoonbroodt, 2018). As a result of the closures of schools and child care facilities in response to the pandemic, there was an increased demand for within-household child care. In a married family, this increased responsibility could be shared. In a single-parent family, the burden likely fell completely on the single parent unless there was an extra adult in the household, such as an unmarried partner, grandparent, aunt, or college student (informal care coming from outside the household was discouraged due to calls for social distancing).

However, even among full-time dual-earner couples, women spend more time caring for children than do men (Alon et al., 2020a). Perhaps this is because the man is expected to be the breadwinner in the family (Allred, 2018; Bertrand et al., 2015). However, there is prior evidence from time-use surveys that a reduction in work-related activities during the Great Recession, when male-dominated sectors such as manufacturing and construction were especially hard-hit, led to men shifting relatively more daily hours toward their children, while mothers’ time with children was invariant to macroeconomic conditions (Aguiar et al., 2013; Bauer & Sonchak, 2017). More recently, Pabilonia and Vernon (2020) find that, when working remotely, fathers shift some of the reduction in their commute time to primary child care, while there is no change in primary child care time for mothers. Some of that increase in fathers’ time is during typical working hours.

Concurrent research on the early effects of the pandemic on the labor market finds that women, particularly those with children, are more affected than men on average (Montenovo et al., 2020; Zamarro & Prados, 2021). This is partly due to women’s employment being concentrated in service-oriented sectors of the economy classified as “nonessential” (Alon et al., 2020a). However, it also is due to the increase in child care responsibilities as schools and child care facilities closed, affecting parents’ ability to work outside (and sometimes inside) the home. Sevilla and Smith (2020), however, found a drop in the gender child care gap in the UK, as furloughed men picked up some of the increase in household-provided child care. Using the CPS and focusing on parents of school-aged children, Heggeness (2020) compares labor market effects in U.S. states with early and late school closures. She finds that mothers in early closure states were 68.8% more likely than mothers in late closure states to be employed but absent from work because of the shutdowns. Of those remaining active at their job, mothers had higher work hours relative to fathers, as fathers reduced their work hours to share in the increased child care responsibilities resulting from the closures. Descriptive analyses based on the Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking Survey indicate that 33% of working mothers in two-parent households provided all the care for children while schools were closed in early April, while only 11% of working fathers provided all the care (Zamarro & Prados, 2021).

Our contribution

Gimenez-Nadal et al. (2012) and Lim (2019) link both the self-employment and intra-household allocation literature, finding that Spanish and American mothers, respectively, choose self-employment to gain work location and schedule flexibility. However, these are pre-COVID-19 papers and do not examine how a shock such as COVID-19 may affect the employment and hours of work of these mothers. Our paper examines the effects of COVID-19 on the employment and hours of work of all unincorporated self-employed workers and then breaks the effects down by gender, marital status, and parental status. Fairlie (2020) examines the effects of COVID-19 on the number of active business owners by gender and race/ethnicity. However, he does not focus on the unincorporated self-employed nor does he do breakdowns by marital and parental status for this worker type as we do. In addition, we estimate panel data models while he compares weighted aggregates across demographic groups. Our results provide evidence that, although married mothers may have chosen self-employment to gain flexibility, they still were harder hit in terms of employment and hours worked than married fathers. Thus, married mothers’ gains in the labor market were partially erased because COVID-19 induced a return to gender roles and household specialization.

Data

The objective of this paper is to examine changes in the employment and work hours of the unincorporated self-employed, using matched individual-level data from the CPS basic monthly files for February through May of 2020 for those initially self-employed and at work in February 2020.5 February 2020 is considered a normal month, and March, April, and May of 2020 were months affected by the COVID-19 shutdowns. School closures for primary and secondary students occurred for the most part after the March CPS reference week. The CPS reference week typically includes the 12th of the month and ended in March on the 14th.6 The World Health Organization (WHO) did not announce the pandemic until March 11, although media coverage of the novel coronavirus picked up in early March after several cases were identified in Washington State at the end of February and people had already started to change their behavior in response to the news reports. Nine states announced state-wide emergencies prior to the CPS March reference week, but state-wide business closures were not mandated until late March.7 Therefore, the effects are expected to be smaller in March than in April. If the re-openings were effective, the effects might be smaller in May than in April, as well.

The CPS interviews a panel of households to collect economic, education, and demographic data about the household members for 4 months, then does not interview them for 8 months, and then re-interviews them again for 4 months. Each month, there are eight rotation groups of households. Those households which are in their first or fifth month in the sample plausibly can be followed each month from February to May, while those in their second and sixth month in the sample can be followed from February to April, and so forth. Thus, each subsequent month, the sample of potential continuers falls (approximately 75% in the second month of the panel, 50% in the third month, and 25% in the fourth month). However, in any given month, a household may also choose not to respond. For example, there may be a response in February and in April, but not in March and May, for an individual interviewed for the first time in February.8

In our analyses, we examine the effects of the pandemic on non-institutionalized civilian adults aged 18 and older.9 Worker type is determined by class of worker status on their primary job in February, and those with jobs are required to be at work during the reference week in February (rather than employed but absent). We begin by including all workers interviewed in February through May 2020 who were employed and at work in February (for the RE models). This sample includes an unbalanced panel of 48,570, 31,592, 20,690, and 10,076 employees; 2276, 1521, 1045, and 530 incorporated self-employed workers; and 3400, 2299, 1513, and 776 unincorporated self-employed workers, in February, March, April, and May, respectively. After showing that unincorporated self-employed workers are a particularly vulnerable group of workers, we then focus on this group only, to examine differences by gender, marital status, parental status, feasibility of a remote job, and essential industry designation.

After examining the full results from the RE models, we also examine more parsimonious DDD models that interact the treatment with gender or class of worker. For these, we use a balanced panel of individuals who were employed and at work in February 2019 or 2020 and subsequently interviewed in April of 2019 or 2020 (excluding March).10 Comparing the same months across 2019 and 2020 controls for seasonal differences. In 2019, our sample includes 22,090 individuals who were employees, 1001 individuals who were incorporated self-employed, and 1509 individuals who were unincorporated self-employed. In 2020, our sample includes 20,684 individuals who were employees, 1045 individuals who were incorporated self-employed, and 1513 individuals who were unincorporated self-employed.

A general concern about the CPS data collected during the first few months of the pandemic has been a spike in those reporting employed but absent for “other reasons.” Respondents who reported not working due to efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 should have been classified as unemployed on temporary layoff, but many were misclassified as employed but absent (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020a, b, c). For this reason, this analysis focuses on changes in employed and at work status for those who were self-employed and at work in February, i.e., those with positive hours. However, we do not require them to still be classified as self-employed workers in subsequent months to be counted as employed and at work for our main analyses.11

Additional information included in the analysis concerns the plausibility that an individual’s job (or their spouse’s job, if applicable) can be done entirely remotely. This is referred to in the analysis as a remote job. The remote job variable is based on Dingel and Neiman (2020), who measured the feasibility of an occupation being done entirely at home based on job tasks reported in the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) surveys, with some additional tweaks to match the change from the 2010 Census codes to the 2018 Census codes in the 2020 CPS.12 In most cases, the remote job variable takes a value of 0 for not being able to be done remotely and 1 for being able to be done entirely remotely. However, in several cases, only part of occupation in the CPS could be classified as being able to be done remotely, and so the value reflects the share employed in the occupation who can work remotely.

In addition, information about whether an individual (or spouse) worked in an essential industry is used. The essential industry variable is based upon Delaware’s nonessential closed business criteria, which is reported at the 4-digit NAICS level and thus can be matched to the CPS data at the detailed industry level (Delaware Division of Public Health, Coronavirus Response, 2020). For three detailed CPS industries (Charter Bus Industry, Cable and Other Subscription Programming, and Real Estate), the September 2019 Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) is used to record the nonessential employment share.

Descriptive statistics: labor market differences by worker type, gender, marital status, and parental status

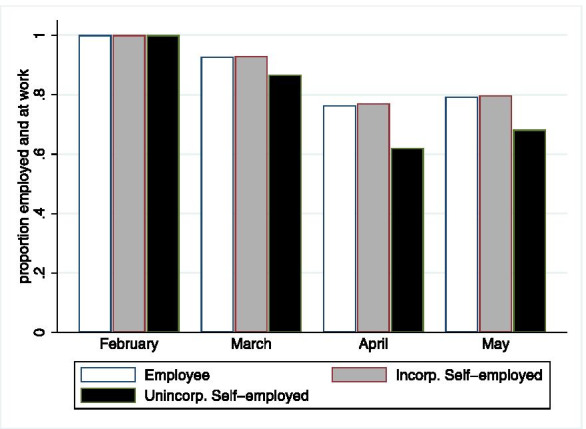

Figure 1 shows the decline in employment by worker type (employee, incorporated self-employed, and unincorporated self-employed) from February through May for those who were working in February 2020.13 In March, as voluntary social distancing began, employment was lower for all groups than in February, with 93% of employees and the incorporated self-employed working. The unincorporated self-employed were hit the hardest, with only 87% working in March. In April, as closures were fully realized, employment was even lower for all three groups. Again, the unincorporated self-employed fared the worst, with only 62% working compared to 77% of the incorporated self-employed and 76% of employees. In May, as employment began to increase again in response to the relaxation of some COVID-19 restrictions, all three groups had improved employment, with employees and the incorporated self-employed at about 80% of February employment but the unincorporated self-employed still far behind at 68% of February employment (the rebound in employment from April to May was not statistically significant for the incorporated self-employed).

Fig. 1.

Employed and at work in 2020 by worker type. Note: All workers were employed and at work in February 2020. For employees, N = 48,570, 31,592, 20,690 and 10,076 for consecutive months. For incorporated self-employed, N = 2276, 1521, 1045, and 530 for consecutive months. For unincorporated self-employed, N = 3400, 2299, 1513, and 776 for consecutive months. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

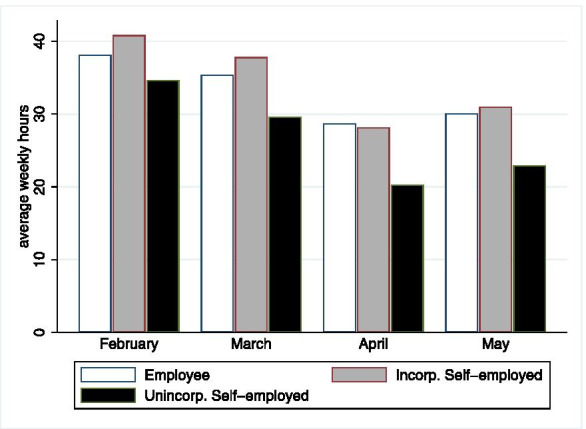

Figure 2 shows the decline in average weekly hours worked by worker type. In February, the unincorporated self-employed worked fewer hours than the incorporated self-employed and employees (35 h per week on average versus 41 h and 38 h, respectively). Again, we see that the unincorporated self-employed were hardest hit, with significant reductions in hours of work. In March, hours of work declined to 30 h per week for the unincorporated self-employed, 38 h per week for the incorporated self-employed, and 35 h per week for employees. In April, hours per week fell even farther, to 20 h for the unincorporated self-employed, 28 h for the incorporated self-employed, and 29 h for employees. In May, hours of work started to bounce back slightly for all workers (a 2–3-h increase on average).

Fig. 2.

Average weekly hours worked in 2020 by worker type. Note: All workers were employed and at work in February 2020. For employees, N = 48,570, 31,592, 20,690, and 10,076 for consecutive months. For incorporated self-employed, N = 2276, 1521, 1045, and 530 for consecutive months. For unincorporated self-employed, N = 3400, 2299, 1513, and 776 for consecutive months. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

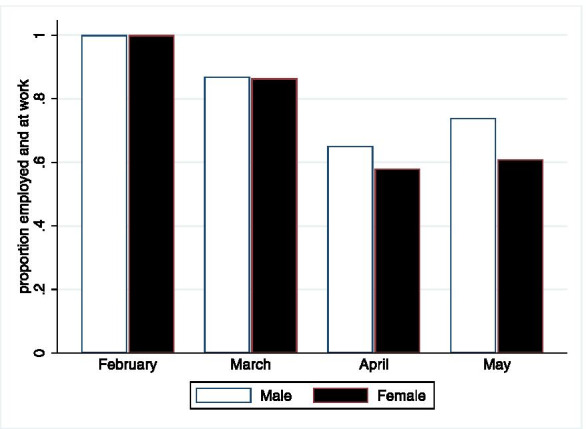

Focusing on the hardest-hit group (the unincorporated self-employed), Fig. 3 shows the decline in employment by gender. In March, there is no difference by gender. However, in April, only 65% of the men and 58% of the women remained at work. Thus, while both men and women among the unincorporated self-employed suffered reduced employment in April, the shutdown had a statistically significant larger effect on women.14 In May, given the partial re-openings, 74% of unincorporated self-employed men and 61% of unincorporated self-employed women were working. For women, the difference between April and May was not statistically significantly different. Thus, men appear to be bouncing back while women do not. This may be due to gender roles, where the man is expected to be the breadwinner in the family (Allred, 2018; Bertrand et al., 2015) and the fact that schools and many child care facilities had not yet re-opened as of May.

Fig. 3.

Unincorporated self-employed who were at work in 2020. Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 2054, 1364, 860, and 442 for consecutive months. For females, N = 1346, 935, 653, and 334 for consecutive months. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

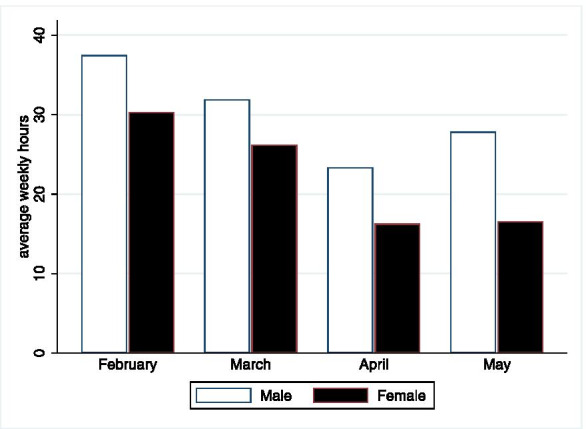

Figure 4 shows the decline in average weekly hours worked by gender for the unincorporated self-employed. In February, self-employed men worked about 37 h per week and women worked about 30 h per week. Many women may have been more likely to be secondary earners, already working part-time to take care of children. However, hours of work decreased for both because of COVID-19. In March, hours of work declined to 32 h per week for men, on average, and to 26 h per week for women. In April, hours of work fell even farther, to 23 h per week for men and 16 h for women. In May, hours started to bounce back for men (back to 28 h per week), but there was little change for women.

Fig. 4.

Average weekly hours worked by the unincorporated self-employed in 2020. Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 2054, 1364, 860, and 442 for consecutive months. For females, N = 1346, 935, 653, and 334 for consecutive months. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

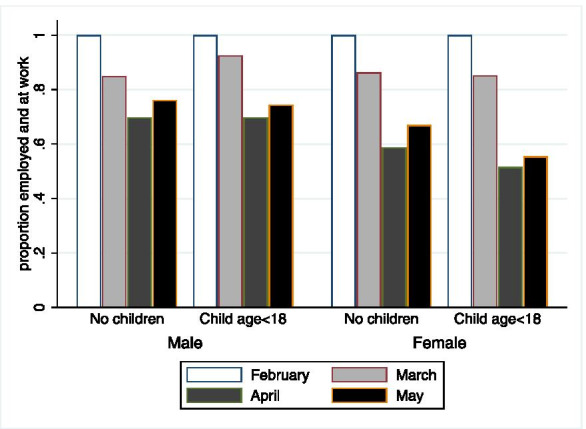

Figure 5 shows how gender and parental status are related to employment for unincorporated self-employed workers who were married. Married individuals can trade-off housework and child care tasks with their spouses, and so individuals in these households have greater flexibility than those in single-parent households, all else equal. Again, we see a decline in employment for everyone between February and April and an increase from April to May. However, the declines are much larger for married women than for married men in April, especially those with children, and the rebound in May is smaller for married women with children than for those without. Having children reduces the rebound in May for married men, as well.

Fig. 5.

Unincorporated self-employed who were at work (married individuals, by gender, and parental status). Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 1333, 904, 573, and 287. For females, N = 841, 573, 416, and 214. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

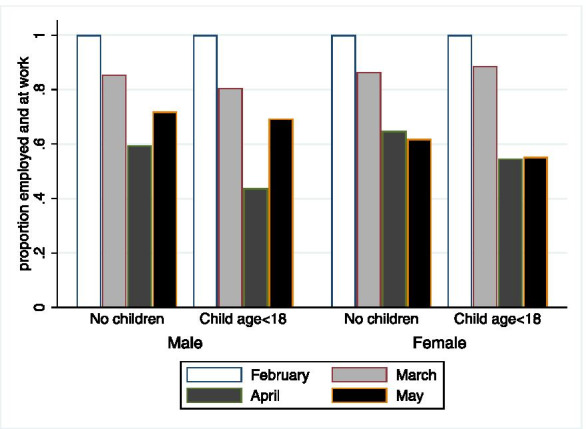

Figure 6 shows how gender and parental status are related to employment for unincorporated self-employed who were single. Single individuals do not necessarily have a partner to help with household tasks such as caring for children.15 Comparing Fig. 6 to Fig. 5, single men had larger declines in employment from February through April than married men. There is an especially large drop for single fathers with household children in April. However, single fathers experienced a large increase in employment in May, getting them almost to the same employment level as single men without children. Single women also experienced a drop in employment in March and April, with a slightly larger drop for single mothers than for non-mothers in April (though the results were not statistically significant at conventional levels). However, single women, with or without children, did not experience the rebound in employment in May that married individuals or single men did.

Fig. 6.

Unincorporated self-employed who were at work (single individuals, by gender, and parental status). Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 721, 460, 287, and 155. For females, N = 505, 362, 237, and 120. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

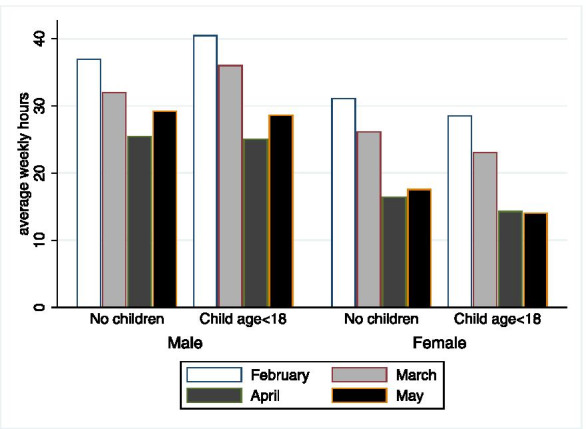

Figure 7 shows how gender and parental status are related to average weekly hours of work unincorporated self-employed workers who were married. In February, married men without children worked approximately 37 h, while married men with children worked about 41 h. However, in April, married men worked only 25 h, regardless of parental status. Women worked substantially less than men in all months, and women with children worked fewer hours than women without children, although the latter differences were only statistically significantly different from zero in February.

Fig. 7.

Average weekly hours worked by the unincorporated self-employed (married individuals, by gender and parental status). Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 1333, 904, 573, and 287. For females, N = 841, 573, 416, and 214. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

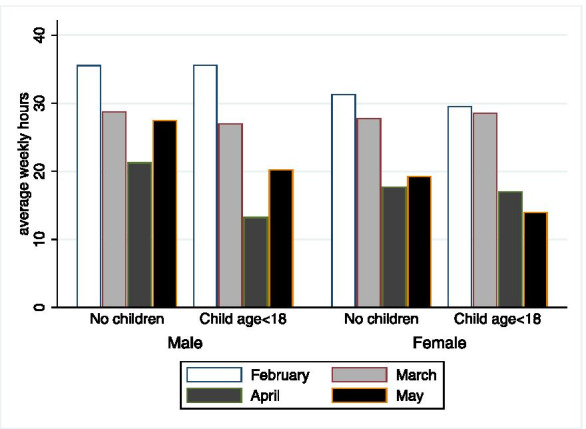

Figure 8 shows how single self-employed workers’ average weekly hours were affected, by parental status and gender. Theirs is a similar story to that for married workers, but there is a huge drop in hours for single fathers in April compared to married fathers. Single fathers in April have an even lower number of work hours, on average, than single mothers, though the difference is not statistically significant. However, single fathers rebound in May, while single mothers do not. Appendix Table 7 provides greater detail about the descriptive statistics of the unincorporated self-employed sample, including a breakdown by the presence and age of children, given the different amounts of supervision and help with online schooling that were necessary during the school closures.

Fig. 8.

Average weekly hours worked by the unincorporated self-employed (single individuals, by gender, and parental status). Note: All workers were unincorporated self-employed and at work in February 2020. For males, N = 721, 460, 287, and 155. For females, N = 505, 362, 237, and 120. Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 7.

Mean employment and hours worked in 2020 by marital and parental status (Unincorp. self-employed)

| Sample | February | March | April | May |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Employed and at work | ||||

| Married | ||||

| Males | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.70 | 0.75 |

| No children | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.76 |

| Child age < 6 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.66 | 0.81 |

| Child age 6–17 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Females | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.56 | 0.61 |

| No children | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.67 |

| Child age < 6 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 0.57 |

| Child age 6–17 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| Single | ||||

| Males | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.56 | 0.71 |

| No children | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.72 |

| Child age < 6 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.94 |

| Child age 6–17 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 0.37 | 0.67 |

| Females | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.60 |

| No children | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.62 |

| Child age < 6 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 0.55 |

| Child age 6–17 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.57 | 0.64 |

| Panel B. Average weekly hours | ||||

| Married | ||||

| Males | 38.57 | 33.85 | 25.30 | 29.00 |

| No children | 37.02 | 32.07 | 25.48 | 29.26 |

| Child age < 6 | 39.18 | 35.57 | 24.54 | 31.41 |

| Child age 6–17 | 40.56 | 35.97 | 24.10 | 27.84 |

| Females | 30.04 | 24.90 | 15.52 | 15.93 |

| No children | 31.13 | 26.22 | 16.48 | 17.61 |

| Child age < 6 | 25.79 | 18.01 | 11.89 | 13.12 |

| Child age 6–17 | 29.45 | 24.67 | 15.33 | 15.40 |

| Single | ||||

| Males | 35.61 | 28.46 | 19.60 | 25.87 |

| No children | 35.60 | 28.81 | 21.30 | 27.55 |

| Child age < 6 | 37.82 | 30.62 | 18.81 | 27.75 |

| Child age 6–17 | 36.00 | 24.64 | 11.15 | 19.17 |

| Females | 30.83 | 28.10 | 17.54 | 17.69 |

| No children | 31.35 | 27.85 | 17.73 | 19.30 |

| Child age < 6 | 25.57 | 24.81 | 20.49 | 15.30 |

| Child age 6–17 | 30.60 | 29.66 | 17.21 | 15.67 |

| Observations | 3400 | 2299 | 1513 | 776 |

Note: CPS final weights used. Sample restricted to those who were employed and at work in February

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Models used to show initial COVID-19 impacts

Two types of models are estimated to examine the initial differential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the employment and hours of the unincorporated self-employed. These impacts included both demand-side and supply-side impacts. On the demand side, unincorporated self-employed workers reduced or eliminated their work hours due to government restrictions on the types of goods and services that could be sold. In addition, due to stay-at-home orders and/or the fear of contracting COVID-19, consumers reduced their face-to-face consumption of goods and services. On the supply side, self-employed workers may not have wanted to work because of fears regarding COVID-19 or had to stop working to care for and/or to educate their children due to school closures. Our models are reduced-form models which cannot disentangle these demand- and supply-side effects. Our primary specifications are RE models. These exploit the richness of the data to examine how employment and hours of work changed as social distancing and shutdowns began to occur in March, were more widespread and more often mandatory in April, and partial re-openings began in May. Month dummy variables capture these effects and are interacted with gender, marital status, age of children, occupation type (remote work plausible or not), and industry type (essential or not), to determine whether the effects differ for the different groups. Furthermore, the RE models also are estimated separately for subgroups defined by marital and parental status.

The second type of models, DDD models, do not examine the evolution of employment changes as social distancing and shutdowns began, became complete, and then began being rescinded. Instead, they consider the change from February to April as a single “treatment” and examine the effect of this treatment on employment and hours of work. While these models do not allow multiple interactions with the treatment as the RE models do (we interact the treatment with gender only and examine demographic sub-samples), they do net out time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity that the RE models do not. However, we do not expect this to be an issue for the RE model estimates, given our extensive set of controls.

RE models

We estimate several RE models by ordinary least squares (OLS) as follows:

| 1 |

where Eit is an indicator for whether individual i in month t is employed and at work during the reference week and 0 otherwise.16 Wi is a vector of key regressors measured in February 2020 (to avoid changes potentially caused by the treatment/shutdowns) that we interact with month. When we examine unincorporated workers, these include dummies for gender, marital status, age of children (any household child age < 6, any household child age 6–17), respondent’s job is a plausibly remote job, and respondent’s job is in an essential industry.17 Mt is a vector of month dummy variables for March, April, and May of 2020. Wi*Mt are the interactions between the key regressors included in Wi and month. The matrix Xi includes additional control variables measured as of February 2020. These include age and age squared, the number of extra adults in the household (besides a spouse or cohabiter), and indicators for older than age 65, education (high school degree, some college, bachelor’s degree, advanced degree), race (African-American, other race), Hispanic ethnicity, cohabitation status, immigrant status, living in a metropolitan area, state of residence, own major industry, own major occupation, spouse’s major industry, and indicators for whether a respondent’s spouse is employed, in a remote job, and in an essential industry. μi is the unobserved, person-specific effect, assumed to be uncorrelated with the other included regressors, and εit is the error term. The constant term β0 and the vectors of coefficients β1, β2, β3, and β4, are to be estimated. The key coefficient vectors are β2 and β3, as these give the levels and interaction effects of the treatment (i.e., the shutdowns). The models control for clustering by household, because in some cases both the respondent and his or her spouse are unincorporated self-employed workers and thus both are in the sample.

To examine the impact of COVID-19 on hours worked last week, we estimate tobit RE models via maximum likelihood as follows:

| 2 |

where Hit* is a latent variable for desired hours behind the observed hours variable Hit and the other variables are defined above. ai is the unobserved, person-specific effect, assumed to be uncorrelated with the other included regressors. The constant term γ0 and the coefficient vectors, γ1, γ2, γ3, and γ4, are to be estimated, and the error term, νit, is normally distributed with a mean of 0 and variance σ2.

DDD models

We also estimate DDD models for which there is assumed to be one “treatment” that occurred in April 2020. The control group includes those sampled in both February and April 2019 and the treated group includes those sampled in both February and April 2020. We examine the initial differential effects of social distancing and the widespread shutdowns on employment and hours in April 2020 by estimating linear models of the following form:

| 3 |

where Yit is an indicator for whether individual i was employed in month t or hours worked last week for individual i in month t.18 hi is an indicator variable for female.19 COVID equals 1 in April 2020 when the COVID-19 shutdowns were widespread and 0 otherwise. The effect of COVID for males, i.e., the difference-in-differences estimator, is α2. The differential effect for females, i.e., the triple-difference estimator, is α3. These models explore only the gender differential effect but are estimated for several demographic sub-samples (married, married parents, etc.). The Aprilt dummy is included to control for seasonal differences. Year2020t equals 1 if the individual is in the treated group (interviewed in 2020) and 0 otherwise. The model also allows for differential seasonal factors by gender (Aprilt*hi) and a gender-specific time trend (Year2020t*hi). The matrix Xit includes the individual, spatial, and job characteristic controls specified earlier, which improves the model precision and potentially controls for any compositional differences, and ωit is the error term.20 We estimate these models by OLS and cluster standard errors at the household level.

Differential initial impacts of COVID-19

Effects of COVID-19 by the type of worker

We begin by showing the initial impacts of COVID-19 on employment and hours by type of worker. Because the coefficients from the RE models in Eqs. (1) and (2) are difficult to interpret directly when numerous interaction terms are included and we want to compare all three worker types, we instead show differences by type of worker across time in the predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and the predicted hours of work.21 The first three columns of Table 1 show the differences in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work. Examining across time, the probability of employment was lower for all groups of workers in March, April, and May compared to February. The greatest losses occurred in April, when the most restrictions were in place, and there was some improvement in May, when restrictions began to be lifted. The unincorporated self-employed suffered a 14 percentage point loss in employment in March compared to February, a 35 percentage point loss in April compared to February, and a 30 percentage point loss in May compared to February. Employees were slightly better off than the unincorporated self-employed, with a reduction in employment of only 7 percentage points in March compared to February, 22 percentage points in April compared to February, and 19 percentage points in May compared to February. The differences in effects across these worker types are statistically significant. Although the incorporated self-employed suffered losses in employment, they lost only 7 percentage points in employment in March compared to February, 21 percentage points in April compared to February, and 18 percentage points in May compared to February. These are statistically significantly different from the unincorporated self-employed; however, they are not statistically significantly different from employees. Thus, we see that the unincorporated self-employed are a particularly vulnerable group.

Table 1.

Differences in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked, by worker type in February 2020 (RE models)

| Worker types | Employed and at work | Hours worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | |

| Unincorporated self-employed (SE) | − 0.14** (0.01) | − 0.35** (0.01) | − 0.30** (0.02) | − 5.44** (0.36) | − 14.63** (0.55) | − 12.30** (0.72) |

| Incorporated SE | − 0.07** (0.01) | − 0.21** (0.01) | − 0.18** (0.02) | − 3.40** (0.45) | − 12.81** (0.68) | − 9.84** (0.94) |

| Employee | − 0.07** (0.00) | − 0.22** (0.00) | − 0.19** (0.00) | − 2.85** (0.08) | − 9.94** (0.14) | − 8.35** (0.17) |

| Differences between worker types | ||||||

| Unincorporated SE-incorporated SE | − 0.07** (0.01) | − 0.14** (0.02) | − 0.12** (0.02) | − 2.04** (0.58) | − 1.82* (0.87) | − 2.46* (1.18) |

| Unincorporated SE-employee | − 0.07** (0.01) | − 0.13** (0.01) | − 0.12** (0.02) | − 2.60** (0.37) | − 4.69** (0.57) | − 3.94** (0.74) |

| Employee-incorporated SE | 0.00 (0.01) | − 0.01 (0.01) | − 0.01 (0.02) | 0.55 (0.46) | 2.87** (0.69) | 1.48 (0.95) |

Notes: N = 124,288. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. Control variables include a quadratic in age and the number of extra household adults (besides a spouse or cohabiter) and indicators for older than age 65, month (March, April, May), marital status, cohabitation status, gender, education (high school, some college, bachelor’s degree, advanced degree), race (African-American, other race), Hispanic ethnicity, any household child age < 6, any household child age 6–17, plausible remote job, job in essential industry, immigrant status, spouse employment, spouse has remote job, spouse works in essential industry, lives in a metropolitan area, own major industry, own major occupation, spouse major industry, and state fixed effects; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Columns 4–6 of Table 1 show the differences in predicted hours worked last week.22 The unincorporated self-employed saw over 5 fewer hours of work in March than in February, almost 15 fewer hours in April than in February, and over 12 fewer hours in May than in February. The incorporated self-employed fared somewhat better, losing only about 3 h in March compared to February, about 13 h in April compared to February, and about 10 h in May compared to February. Employees lost about 3 h in March, about 10 in April, and about 8 h in May, all compared to February. Thus, the incorporated self-employed took a harder hit to hours of work than both the incorporated self-employed and employees in April relative to February. Again, as we did with employment, we can conclude that the unincorporated self-employed were the most vulnerable worker type in terms of hours reductions due to the pandemic.23 Therefore, in the rest of our analyses, we focus on differential effects among the unincorporated self-employed.

Key results for the unincorporated self-employed

Table 2 focuses on the unincorporated self-employed and shows the differences in the predicted probabilities of being employed and at work (columns 1–3) and the predicted hours of work (columns 4–6) across time and between groups defined by gender and marital status.24 Again, the underlying predictions are from the RE models. Regarding the employment effects, we observe that females fared worse than males in April (by 7 percentage points) and May (by 10 percentage points) compared to February. This makes sense if the demand shocks from COVID-19 were higher in female-dominated jobs (Alon et al., 2020b). However, because our analyses control for major occupation and industry, these shocks would refer to occupations at a finer level. Another possibility is that women were more wary of contracting COVID-19 than men (as they are more risk-averse on average, see Borghans et al., 2009) and thus were more likely to leave employment. Yet still another possibility is that the closing of schools and daycares may have caused women to be more likely to leave employment than men if they took on the role of caring for children at home presumably due to prescribed gender roles and the division and specialization of labor within households. Indeed, we find that married women were much worse off in terms of employment reductions compared to February than married men (being 4 percentage points less likely to be employed and at work than married men in March, 14 percentage points less likely in April, and 13 percentage points less likely in May) and that married men were more likely to be employed than single men (5 percentage points more likely in March and 13 percentage points more likely in April), providing suggestive evidence of this latter possibility. More evidence for this possibility is found in Table 3 where we examine the effects of COVID-19 on employment using the sub-sample of married individuals.25 Columns 1–3 of Table 3 show that married mothers of young children were less likely to be employed than fathers of young children, 16 percentage points less likely in April compared to February, and 25 percentage points less likely in May compared to February. Married mothers of school-aged children also were less likely to be employed than married fathers of school-aged children, 7 percentage points less likely in March, 18 percentage points less likely in April, and 14 percentage points less likely in May, all compared to February. Even married women without children were less likely to be employed than married men without children in April compared to February, but only 11 percentage points less likely, a smaller reduction than for married women with children. This suggests that specialization within the household did not happen solely because of children. Thus, there may be some support for the demand-side shock and risk-aversion explanations.

Table 2.

Differences between groups and across months in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked for the unincorporated self-employed (RE models)

| Differences between groups | Employed and at work | Hours worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female-male | − 0.01 (0.01) | − 0.07** (0.02) | − 0.10** (0.03) | 0.81 (0.65) | − 0.17 (0.92) | − 3.52** (1.26) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married-single | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.60 (0.74) | 1.10 (1.06) | 0.79 (1.40) |

| Marital/gender status | ||||||

| Married women-married men | − 0.04* (0.02) | − 0.14** (0.03) | − 0.13** (0.04) | − 0.97 (0.78) | − 1.65 (1.10) | − 4.75** (1.46) |

| Single women-single men | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.04) | − 0.04 (0.05) | 4.03** (1.16) | 2.90 (1.65) | − 1.17 (2.28) |

| Married men-single men | 0.05* (0.02) | 0.13** (0.03) | 0.07 (0.04) | 2.67** (0.97) | 3.26* (1.45) | 2.58 (1.92) |

| Married women-single women | − 0.02 (0.02) | − 0.07 (0.04) | − 0.02 (0.05) | − 2.33* (1.07) | − 1.29 (1.45) | − 1.01 (1.95) |

Notes: N = 7988. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 3.

Differences between groups and across months in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked for the unincorporated self-employed (RE models) (married individuals)

| Differences between groups | Employed and at work | Hours worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | |

| Mothers-fathers with child age < 6 | − 0.09 (0.05) | − 0.16* (0.07) | − 0.25** (0.09) | − 4.55* (1.99) | − 0.79 (2.67) | − 8.45** (3.22) |

| Mothers-fathers with child age 6–17 | − 0.07* (0.03) | − 0.18** (0.05) | − 0.14* (0.06) | − 1.84 (1.35) | − 0.50 (1.82) | − 1.69 (2.26) |

| Childless women-childless men | − 0.01 (0.02) | − 0.11** (0.04) | − 0.09 (0.05) | 0.20 (0.99) | − 2.28 (1.43) | − 5.32** (2.00) |

Notes: N = 5141. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Going back to the results in Table 2, columns 4–6 show the differences in predicted hours worked between groups across time. In terms of hours, females were worse off than males in May compared to February (about 3.5 h worse off), especially among married individuals (5 h worse off). Again, these effects could be the result of the COVID-19 demand shocks differentially affecting employment and hours within an occupation and industry and/or a reduction in supply due to the greater risk aversion of women. They also could be due to specialization and gender norms. Support for this last explanation can be seen when we compare predicted hours for married individuals by parental status in Table 3. In columns 4–6 of Table 3, we see that the hours of mothers with young children fell more than the hours of fathers with young children in March and May compared to February (by 5 h more in March and by over 8 h more in May). However, specialization is not solely the result of child care needs, as childless married women worked 5 fewer hours than childless married men in May compared to February, suggesting that demand-side shocks and/or risk-aversion may be playing a role in the intensity of women’s labor market participation.

Additional analyses: DDD models

In Table 4, we show the differential initial effects of COVID-19 on the employment and hours of work of the married unincorporated self-employed using estimates from the DDD models. We specify the COVID-19 treatment as occurring in April of 2020 only and allow only one interaction with the treatment (a female dummy). Therefore, they are not directly comparable to the estimates from the RE models. Each panel presents results for a separate regression.26 Panel A shows the overall effects of COVID-19 on married, unincorporated self-employed workers. Such individuals were 23 percentage points less likely to be employed and at work and worked over 11 fewer hours per week because of COVID-19. In panel B, we use the same sample and examine whether there were differential effects by gender. Among married individuals, women were less likely to be employed and at work due to COVID-19 than men, but the estimate is imprecise. When examining all married parents in panel C, we see that mothers were 11 percentage points less likely to be employed due to COVID-19 than fathers. This is consistent with the idea that COVID-19 sent mothers back into the home to care for children as per gender norms. However, further breakdowns by age of children (panels D and E) do not reveal any statistically significant female effects, likely due to the smaller sample sizes. Married women without children (panel F) were not more greatly affected by COVID-19 in April 2020 than married men without children.

Table 4.

Differential effects of COVID-19 in April 2020 on being employed and at work and hours worked of married unincorporated self-employed workers (DDD models)

| Sample | N | Variables | Employed and at work | Hours worked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. All married | 3884 | COVID | − 0.23** (0.02) | − 11.27** (0.87) |

| Panel B. All married | 3884 | COVID | − 0.21** (0.02) | − 10.92** (1.07) |

| COVID × female | − 0.06 (0.03) | − 0.84 (1.48) | ||

| Panel C. All married parents | 1704 | COVID | − 0.22** (0.03) | − 11.70** (1.69) |

| COVID × female | − 0.11* (0.05) | − 1.46 (2.32) | ||

| Panel D. Married with any child age < 6 | 692 | COVID | − 0.25** (0.05) | − 12.48** (2.76) |

| COVID × female | − 0.08 (0.09) | − 1.91 (4.01) | ||

| Panel E. Married with any child age 6–17 | 1396 | COVID | − 0.23** (0.03) | − 12.31** (1.81) |

| COVID × female | − 0.08 (0.06) | − 0.68 (2.456) | ||

| Panel F. Married no children | 2180 | COVID | − 0.19** (0.03) | − 10.47** (1.42) |

| COVID × female | − 0.02 (0.05) | − 0.21 (1.97) |

Notes: Each panel is a separate regression showing the effect of COVID and/or the differential effect of COVID by gender for different parental and/or marital status samples. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables. Regressions also include interactions of the subgroup with month and year; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February and April 2019–2020

Additional analyses: remote job and essential industry status

In Table 5, we again use the RE models to present differences in the predicted probabilities of employment and predicted hours worked across time and groups defined on two job characteristics—plausible remote job status and essential industry status—to see whether these mitigated the effects of COVID-19. Overall, in Panel A, we find that unincorporated self-employed workers with a plausibly remote job were 9 percentage points more likely to be employed and at work in April relative to February than those who did not have a remote job. Those working in an essential industry were more likely to be employed in both April and May relative to February than those who did not work in an essential industry (a 23 percentage point difference and 16 percentage point difference, respectively). Both the remote job and essential industry effects make sense if being able to work remotely and working in an essential industry reduced or eliminated the demand or supply shocks for these workers.

Table 5.

Differences between groups defined by job characteristics and across months in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked for the unincorporated self-employed (RE models)

| Differences between groups | Employed and at work | Hours worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | |

| Panel A. All unincorporated self-employed (N = 7988) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | − 0.00 (0.02) | 0.09** (0.03) | 0.04 (0.04) | − 0.59 (0.77) | 2.47* (1.08) | 0.91 (1.45) |

| Essential-not essential industry | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.23** (0.03) | 0.16** (0.04) | 0.73 (0.84) | 10.76** (1.44) | 7.41** (1.55) |

| Panel B. All married (N = 5141) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | − 0.01 (0.02) | 0.08* (0.03) | 0.03 (0.04) | − 0.47 (0.94) | 2.21 (1.32) | 0.21 (1.76) |

| Essential industry-not essential industry | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.23** (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | 1.42 (1.09) | 11.61** (1.48) | 6.98** (1.95) |

| Panel C. Married mothers (N = 860) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.09) | 2.39 (2.00) | 5.27* (2.57) | 2.21 (3.11) |

| Essential industry-not essential industry | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.27** (0.07) | 0.16 (0.09) | 0.73 (2.05) | 11.28** (2.57) | 9.99** (3.07) |

| Panel D. Married fathers (N = 1262) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | − 0.02 (0.03) | 0.15** (0.06) | − 0.01 (0.08) | − 3.25 (2.03) | 2.75 (2.83) | − 2.92 (3.95) |

| Essential industry-not essential industry | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.23** (0.09) | 0.18 (0.13) | 0.72 (3.05) | 8.71* (4.13) | 8.63 (6.04) |

| Panel E. Married women no children (N = 1184) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | − 0.07 (0.04) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.09) | − 2.74 (1.69) | − 0.04 (2.47) | 3.34 (3.48) |

| Essential industry-not essential industry | − 0.03(0.04) | 0.22** (0.07) | 0.06 (0.09) | 1.77 (1.62) | 11.92** (2.34) | 5.42 (3.36) |

| Panel F. Married men no children (N = 1835) | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.06) | − 0.05 (0.07) | 1.60 (1.52) | 1.83 (2.36) | − 2.72 (3.10) |

| Essential industry-not essential industry | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.18* (0.07) | 0.00 (0.08) | 1.85 (1.85) | 10.51** (2.69) | 4.35 (3.08) |

Notes: Each panel represents differences for separate regressions by sub-sample. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

In terms of hours, unincorporated self-employed workers with a plausibly remote job had over 2 more hours of work per week in April relative to February than those who did not have a remote job. Those working in an essential industry had almost 11 more hours of work in April and over 7 in May relative to February than those who did not work in an essential industry. Again, working in a remote job and/or an essential industry appears to have reduced demand or supply shocks to the hours of these workers.

In the remaining panels of Table 5 (panels B–F), we further examine whether there were differential effects of job characteristics for all married individuals and for married individuals by parental status. In panel B, we find that married workers with a plausibly remote job were 8 percentage points more likely to be employed in April relative to February than those who did not have a remote job. Among married mothers, having a remote job mitigated the negative hours effects of COVID-19 in April relative to February by 5 h (panel C). Among married fathers (panel D), having a remote job mitigated the employment effects of COVID-19 in April relative to February (panel D) by 15 percentage points. Among both parents and non-parents in the married sample, we find that working in an essential industry mitigated the employment effects of COVID-19 in April by 18–27 percentage points, depending on the subsample. Regarding the effects of COVID-19 on hours, these were mitigated for all married persons in essential industries in April. In May, the effects were mitigated for married mothers in essential industries.

Conclusion

In this paper, we study the initial impact of COVID-19 on workers by class of worker and find that the unincorporated self-employed experienced the largest reductions in employment and hours of all worker types, highlighting how relatively vulnerable the unincorporated self-employed were. Perhaps this is because they were without a sufficient social safety net in place at the beginning of the pandemic. The negative effects were largest in April 2020, with a small rebound in May 2020. These results suggest significant revenue losses for many small businesses in the early months of the pandemic, which likely resulted in permanent closures for many, as surveys show that few had sufficient cash on hand to cover their expenses in even a short downturn (Bartik et al., 2020; Buffington et al., 2020). They also suggest that it is important for researchers to distinguish between self-employed workers by incorporation status.

Focusing just on the unincorporated self-employed, we find differential effects of COVID-19 by gender that favor men, by marital status and gender that favor married men over married women, and by gender, marital, and parental status that favor married fathers over married mothers. Consistent with the literature on gendered employment effects of COVID-19 on all workers (e.g., Alon et al., 2020b; Heggeness, 2020), we find that self-employed females fared worse than self-employed males in terms of reductions in employment and hours, perhaps because demand shocks from COVID-19 were higher in female-dominated jobs or from supply shocks as more risk-averse women left employment than men. Married women were especially worse off compared to married men, and married mothers especially worse off compared to married fathers. Thus, in addition to the abovementioned demand and supply shocks, married mothers have been forced out of the labor force to care for children presumably due to prescribed gender norms and the division and specialization of labor within households. Having a plausibly remote job and working in an essential industry have mitigated some of these effects. Thus, COVID-19 appears to have set unincorporated self-employed women back in terms of their labor market presence, relegating many of them to the home and reinforcing traditional gender norms. Our finding of gendered employment effects of COVID-19 among the self-employed also has broader implications for the overall employment-to-population ratio in the long run, as female self-employed workers tend to be less likely to lay off their employees (Matsa & Miller, 2014).

A limitation of this paper is that while we estimate the total effect of COVID-19 on employment and hours of work, we are unable to fully disentangle the supply and demand effects. Future research could estimate a more structural model with different data. Another limitation is that although we do examine the effects of COVID-19 on hours, we do not break down our results by full-time versus part-time employment status. Indeed, many self-employed workers may be part-time, as they are using it as a bridge to retirement or as supplementary income to that of the primary earner in the household. This is an avenue worth pursuing in future research. Another limitation is that we cannot examine earnings, because information on earnings is not collected every month in the CPS and so it is not available for all our observations. Future research could use different data to examine the effects of COVID-19 on earnings. Finally, our analyses stop in May, but loosening of restrictions across states over time has occurred since then and not in tandem. Future analyses could exploit this variation across states over time to see how different states' responses to the pandemic affected hours and employment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Hamermesh, Peter Meyer, James Spletzer, and Jay Stewart for helpful suggestions. We thank Thomas Korankye and Nana Twum Owusu-Peprah for research assistance.

Appendix

Table 6.

Differences in predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked for the unincorporated self-employed (RE model) (sample restricted to states with state-wide emergency declarations after March 8)

| Differences between groups | Employed and at work | Hours worked | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | March–Feb | April–Feb | May–Feb | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female-male | − 0.01 (0.02) | − 0.06* (0.03) | − 0.08* (0.03) | 1.01 (0.73) | − 0.10 (1.01) | − 3.21* (1.40) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married-single | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.02 (0.04) | − 0.09 (0.83) | 1.19 (1.18) | 0.58 (1.55) |

| Marital/gender status | ||||||

| Married women-married men | − 0.04* (0.02) | − 0.14** (0.03) | − 0.12** (0.04) | − 0.78 (0.88) | − 1.83 (1.23) | − 4.86** (1.62) |

| Single women-single men | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.04) | − 0.01 (0.06) | 4.32** (1.30) | 3.22 (1.80) | − 0.12 (2.58) |

| Married men-single men | 0.05* (0.02) | 0.13** (0.04) | 0.07 (0.05) | 2.04 (1.10) | 3.50* (1.59) | 2.77 (2.09) |

| Married women-single women | − 0.04 (0.03) | − 0.08* (0.04) | − 0.04 (0.06) | − 3.06* (1.19) | − 1.55 (1.61) | − 1.97 (2.23) |

| Job characteristics | ||||||

| Remote job-not remote job | − 0.01 (0.02) | 0.09** (0.03) | 0.04 (0.04) | − 1.37 (0.87) | 2.06 (1.21) | 0.62 (1.65) |

| Essential-not essential industry | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.21** (0.03) | 0.15** (0.04) | 1.11 (0.96) | 11.13** (1.30) | 6.98** (1.74) |

Notes: N = 6479. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 8.

Predicted probabilities of being employed and at work and hours worked, by worker type in February 2020 (RE model)

| Worker types | Feb | March | April | May |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of being employed and at work | ||||

| Unincorporated SE | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.65 (0.01) | 0.70 (0.02) |

| Incorporated SE | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.93 (0.00) | 0.78 (0.00) | 0.81 (0.00) |

| Employee | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.93 (0.01) | 0.79 (0.01) | 0.82 (0.02) |

| Hours worked last week | ||||

| Unincorporated SE | 35.52 (0.29) | 29.08 (0.41) | 19.89 (0.55) | 22.23 (0.72) |

| Incorporated SE | 40.52 (0.36) | 37.12 (0.50) | 27.70 (0.68) | 30.68 (0.93) |

| Employee | 38.22 (0.05) | 35.38 (0.09) | 28.28 (0.14) | 29.87 (0.17) |

Notes: N = 124,288. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 9.

Differential effects of COVID in April 2020 on being employed and at work and hours worked, by worker type in February (DDD model)

| Worker types | All (1) | Restricted sample (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Employed and at work | ||

| COVID (reference group = unincorporated SE) | − 0.23** (0.02) | − 0.21** (0.02) |

| COVID × incorporated SE | 0.09** (0.02) | 0.05 (0.03) |

| COVID × employee | 0.07** (0.02) | 0.05* (0.02) |

| Panel B. Hours worked | ||

| COVID (reference group = unincorporated SE) | − 11.01** (0.69) | − 10.78** (1.12) |

| COVID × incorporated SE | 1.80 (1.08) | − 0.67 (1.77) |

| COVID × employee | 3.72** (0.70) | 3.65** (1.14) |

| Observations | 95,684 | 31,328 |

Notes: All workers were employed and at work in February. Column 1 includes those who were observed in February and Aprilof at least 1 year. Column 2 includes those who were observed in all 4 months in order to further minimize concerns that the parallel trends assumption may be violated because of differences in the sample’s composition (note: February means are similar, see Appendix Table 15). Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February and April 2019–2020

Table 10.

Predicted probabilities of being employed and at work for the unincorporated self-employed (RE model)

| Groups | March | April | May |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.61 (0.02) | 0.64 (0.03) |

| Male | 0.87 (0.01) | 0.68 (0.02) | 0.74 (0.02) |

| Married | 0.87 (0.01) | 0.67 (0.01) | 0.71 (0.02) |

| Single | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.63 (0.02) | 0.68 (0.03) |

| Married women | 0.85 (0.02) | 0.59 (0.02) | 0.64 (0.03) |

| Married men | 0.89 (0.01) | 0.73 (0.02) | 0.77 (0.02) |

| Single women | 0.87 (0.02) | 0.66 (0.03) | 0.66 (0.04) |

| Single men | 0.84 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.03) | 0.70 (0.03) |

| Not remote job | 0.87 (0.01) | 0.63 (0.02) | 0.69 (0.02) |

| Remote job | 0.85 (0.01) | 0.70 (0.02) | 0.71 (0.03) |

| Not essential industry | 0.87 (0.02) | 0.51 (0.02) | 0.61 (0.03) |

| Essential industry | 0.86 (0.01) | 0.72 (0.02) | 0.75 (0.02) |

Notes: N = 7988. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 11.

Predicted hours worked for the unincorporated self-employed (RE model)

| Groups | Feb | March | April | May |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 30.90 (0.42) | 25.95 (0.57) | 16.45 (0.67) | 16.72 (0.91) |

| Male | 37.45 (0.33) | 31.69 (0.50) | 23.17 (0.69) | 26.78 (0.91) |

| Married | 35.33 (0.34) | 30.05 (0.49) | 21.11 (0.64) | 23.20 (0.84) |

| Single | 34.00 (0.44) | 28.11 (0.64) | 18.68 (0.84) | 21.08 (1.11) |

| Married women | 30.16 (0.52) | 24.29 (0.69) | 15.27 (0.81) | 15.65 (1.09) |

| Married men | 38.60 (0.41) | 33.69 (0.61) | 25.35 (0.86) | 28.84 (1.12) |

| Single women | 32.13 (0.69) | 28.59 (0.97) | 18.52 (1.19) | 18.63 (1.58) |

| Single men | 35.32 (0.56) | 27.74 (0.86) | 18.82 (1.18) | 22.98 (1.56) |

| Not remote job | 34.44 (0.43) | 29.16 (0.57) | 18.95 (0.69) | 21.67 (0.91) |

| Remote job | 35.54 (0.60) | 29.67 (0.75) | 22.53 (0.90) | 23.68 (1.14) |

| Not essential industry | 35.69 (0.68) | 29.68 (0.86) | 13.72 (0.88) | 18.22 (1.28) |

| Essential industry | 34.48 (0.38) | 29.21 (0.50) | 23.28 (0.69) | 24.43 (0.85) |

Notes: N = 7988. All workers were employed and at work in February. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered by household. See Table 1 for control variables

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the Current Population Survey, February–May 2020

Table 12.

Means for RE sample (unincorporated self-employed)

| Variable | February | March | April | May |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed and at work | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| Hours on the primary job | 34.67 | 29.61 | 20.29 | 22.96 |

| Female | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Age | 49.45 | 49.37 | 49.38 | 48.91 |

| Age 65 plus | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| High school degree | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Some college | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Advanced degree | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Black | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Other race | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Hispanic | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.2 |

| Any child age < 6 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

| Any child age 6–17 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| Married | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.63 |

| Number of extra HH adults | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.52 |

| Cohabiter | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Immigrant | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.21 |

| Remote job | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.42 |

| Essential industry | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.66 |

| Own industry | ||||

| Agriculture and mining | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Construction | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Manufacturing | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Trade, transportation, and utilities | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Information | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Financial activities | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Professional and business services | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |