Summary

Ketohexokinase (KHK) catalyzes the first step of fructose metabolism. Inhibitors of KHK enzymatic activity are being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diabetes. Here, we present a luminescence-based protocol to quantify KHK activity. The accuracy of this technique has been validated using knockdown and overexpression of KHK in vivo and in vitro. The specificity of the assay has been verified using 3-O-methyl-D-fructose, a non-metabolizable analog of fructose, heat inactivation of hexokinases, and depletion of potassium.

For complete details on the use of this protocol, please refer to Damen et al. (2021).

Subject areas: Cell Biology, Cell-based assays, Metabolism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protocol to quantify KHK enzymatic activity in cells and tissues

-

•

Activity in whole lysates is quantified using a luminescence-based method

-

•

KHK is sensitive to temperature and potassium concentrations

Ketohexokinase (KHK) catalyzes the first step of fructose metabolism. Inhibitors of KHK enzymatic activity are being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of NAFLD and diabetes. Here, we present a luminescence-based protocol to quantify KHK activity. The accuracy of this technique has been validated using knockdown and overexpression of KHK in vivo and in vitro. The specificity of the assay has been verified using 3-O-methyl-D-fructose, a non-metabolizable analog of fructose, heat inactivation of hexokinases, and depletion of potassium.

Before you begin

Note: Ketohexokinase activity is resistant to temperature degradation (Malaisse et al., 1989). Hexokinases are degraded at 70°C, therefore, heat can be used to discern between closely related hexokinase and KHK-C activity.

Note: KHK-C activity requires potassium (Sener et al., 1984), whereas FN3K activity is not known to require this cation (Szwergold et al., 2001). It is critical that K+ is used in the reaction mixture and not other cations, such as Na+ or Ca2+.

Basic principle

Consumption of a high-fat diet and sugar-sweetened beverages predisposes to development of obesity, insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Softic et al., 2016)(Softic et al., 2020). Fructose, a component of dietary sugar, has been implicated and targeted against these complications (Attia et al., 2020). However, a reliable protocol to accurately measure fructose metabolism was not available.

Ketohexokinase (KHK) catalyzes the first step of fructose metabolism by phosphorylating fructose to fructose 1-phosphate. There are two KHK isoforms, (Diggle et al., 2009; Diggle et al., 2010). KHK-C is expressed in the liver, kidney and the intestine and is the primary enzyme catalyzing fructose metabolism. KHK-A is expressed ubiquitously, but it has much lower affinity for fructose. Hexokinase 1 (HK1), expressed in the pancreas and the brain and hexokinase 2 (HK2), expressed in the adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, can also metabolize fructose by converting it to fructose 6-phosphate (Helsley et al., 2020). Lastly, fructosamine 3 kinase (FN3K), expressed in red blood cells and the lens of the eye, can phosphorylate fructose to fructose 3-phosphate (Helsley et al., 2020).

A unique feature of KHK-C activity is that phosphorylation of fructose occurs exceedingly fast leading to depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and accumulation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP). On the other hand, phosphorylation of glucose does not increase ADP levels. We have explored this unique feature of KHK-C to approximate its enzymatic activity based on measuring ADP accumulation. In brief, the samples are mixed with fructose, ATP and potassium and ADP accumulation is quantified using luminescent ADP detection assay.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Hepes pH 7.4 | Sigma | RDD002-1KG |

| KCl | Sigma | P9333 |

| Glutathione | Sigma | G4251 |

| CHAPS | VWR | 0465-10G |

| MgCl2 | Sigma | M2383 |

| ATP | Sigma | A2393-1G |

| D-Fructose | Acros | AC161350010 |

| EDTA | Sigma | E5134-500G |

| DTT | Sigma | D0632-1G |

| 3-O-methyl-d-fructose (3OMF) | Syngene a | CAS # 36256-85-6 |

| Tris-Cl pH7.5 | Teknova | T5075 |

| MOPS pH7.2 | Sigma | M1254 |

| Recombinant Human KHK-C | OriGene | TP323488 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| ADP Glo kit | Promega | PAV6930 |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Scientific | 23225 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| HepG2 | ATCC | HB-8065; CVCL_0027 |

| Other | ||

| khk Mouse Lentiviral Particles | OriGene | MR204149L2V |

| 384w PS flat white assay plate | Greiner | 784075 |

| Plate reader | BioTek | SynergyH1 Hybrid |

| Tissue homogenizer | SPEX SamplePrep | Geno/grinder 2010 |

| Stainless Steel Grinding Balls, 5/32 | SPEX SamplePrep | 2150 |

| 2.0 mL Microtubes | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 05-408-146 |

| Centrifuge, refrigerated | Eppendorf | 5415R |

| Electronic Pipette (5–120ul) | Sartorius | 735041 |

| Electronic Pipette (0.5–10ul) | Sartorius | 735111 |

Synthesized according to references (Brady, 1970; Glen et al., 1951), see Figure S1 for 1H NMR spectrum.

Materials and equipment

Note: Prepare all solutions using sterilized, demineralized, ultrapure water (MQ H2O). 18.2 Ω molecular biology grade H2O is highly recommended.

1× assay buffer

| Reagent | Final concentration | Volume (total 5 mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Hepes, pH 7.4 (1M) | 50 mM | 0.25 mL |

| KCl (4 M) | 150 mM | 0.1875 mL |

| MgCl2 (1M) | 4 mM | 0.02 mL |

| CHAPS (10%) | 0.05% | 0.025 mL |

| Glutathione (200 mM) | 1 mM | 0.025 mL |

| MQ water | 4.4925 mL | |

| Hepes and CHAPS can be stored at 4°C. KCl and MgCl2 can be stored at 22°C–25°C for at least one year. Glutathione should be stored at −20°C to −15°C. | ||

2× substrate solution

| Component | 2× concentration | Volume (total 1 mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1× assay buffer | 1× | Up to 1000 μL |

| ATP (10 mM) | 200 uM | 20 μL |

| Fructose or 3OMF (500 mM) | 4 mM | 8 μL |

| Aliquots of ATP can be stored at −20°C to −15°C for up to six months. Freezing/thawing should be avoided. Fructose and 3OMF can be stored at 4°C. | ||

Tissue lysis buffer

| Component | Final conc | Volume (total 5 mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Hepes, pH 7.4 (1 M) | 50 mM | 0.25 mL |

| KCl (4 M) | 150 mM | 0.1875 mL |

| MgCl2 (1 M) | 4 mM | 0.02 mL |

| CHAPS (10%) | 0.05% | 0.025 mL |

| Glutathione (200 mM) | 1 mM | 0.025 mL |

| EDTA (500 mM) | 1 mM | 0.01 mL |

| DTT (1 M) | 1 mM | 0.005 mL |

| MQ water | 4.4775 mL | |

| EDTA can be stored at 22°C–25°C for at least one year. DTT can be stored at −20°C to −15°C. | ||

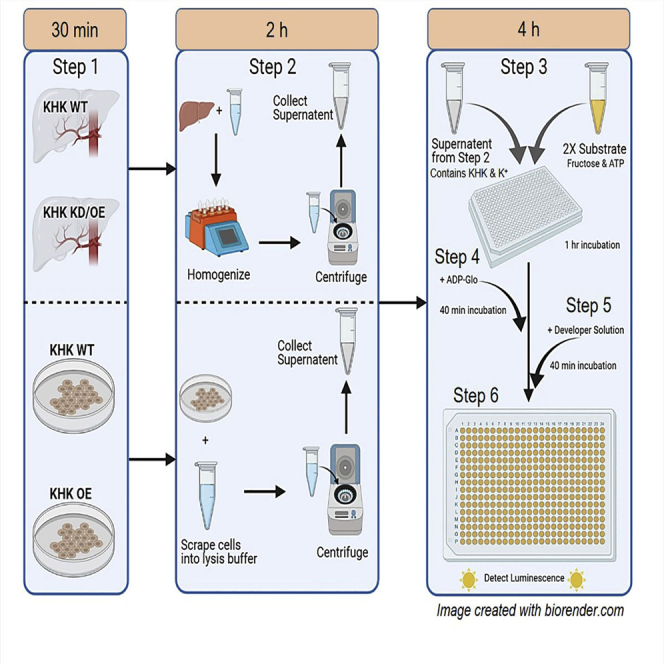

Step-by-step method details

Collect tissue or cells

Timing: 30 min

-

1.

Mice are injected intraperitoneally with Ketamine/Xylazine mixture. When toe pinch response is lost, tissues are harvested, placed in histology cassette and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

-

2.

Tissue collected in liquid nitrogen can be stored at −80°C for at least 3 months.

-

3.

For in vivo negative and positive controls, mice were injected with siRNA against KHK or adeno associated virus containing mouse KHK-C plasmid under TBG promoter, respectively.

Note: KHK siRNA was published previously (Softic et al., 2017). The AAV containing the mouse KHK-C gene was generated by Boston Children’s Hospital Viral Core.

-

4.

Wild type and KHK overexpressing HepG2 cells are washed with PBS and lysed on ice with lysis buffer.

Note: To obtain KHK overexpressing cells, HepG2 cells were infected (MOI=5) with a lentivirus containing the mouse KHK-C gene fused to GFP. After 5 days, cells were sorted for GFP and cultured for 3 weeks to obtain a colony of cells overexpressing KHK.

CRITICAL: Tissues should be snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after harvesting.

Preparation of tissue and cell lysate

Timing: 120 min

Tissue lysate

-

5.

Make enough tissue lysis buffer (300 + 750 μL per sample) and keep on ice.

-

6.

Pre-label 2 mL tubes, place a steel bead into each tube, and chill on dry ice.

-

7.

Cut frozen liver pieces (30–40 mg) on dry ice and place them into pre-cooled 2 mL tubes.

-

8.

Homogenize tissues in 300 μL lysis buffer for 1.5 min at 1,200 rpm using tissue homogenizer.

-

9.

Add 750 μL of lysis buffer and homogenize again for 1.5 min at 1,200 rpm.

-

10.

Centrifuge at 16,000 g (15,000 rpm) for 15 min at 4°C.

-

11.

Transfer 900 μL of tissue lysate into a new 1.5 mL tube.

Note: Ensure to avoid fatty top layer and cell debris pellet.

-

12.

Centrifuge at 16,000 g for 15 min at 4°C.

Note: This centrifugation step helps further remove lipid contamination.

-

13.

Transfer 700 μL into a new 1.5 mL tube.

Note: Again, ensure to avoid fatty top layer.

-

14.

Quantify the amount of protein in each sample.

Cell lysate

-

15.

Seed HepG2 wild type and KHK overexpressing cells at a density of 250,000 cells in a 6-well plate.

-

16.

After two days of culturing, wash cells with 1 mL of 1× PBS.

-

17.

Add 300 μL of lysis buffer on ice.

-

18.

Scrape cells into a pre-cooled 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

-

19.

Sonicate the cells on 30% power for 10 s.

-

20.

Centrifuge the cells for 15 min at 16,000 g, 4°C.

-

21.

Use the cell supernatant and quantify the amount of protein in each sample.

CRITICAL: All processes need to be completed on ice.

Prepare KHK enzyme substrate reaction

Timing: 240 min

-

22.

Prepare 0.025 μg/μL protein homogenate for each sample in 1× assay buffer or 1× assay buffer negative control.

Note: 1× assay buffer contains 150 mM of K+

Note: 1× assay buffer negative control does not contain K+

-

23.

Prepare 2× substrate solution.

Note: 2× substrate solution contains fructose and ATP.

Note: 2× substrate solution negative control does not contain fructose or

Note: 2× substrate solution negative control contains 3-O-methyl-d-fructose.

-

24.

Transfer 2.5 μL of 0.025 μg/μL protein homogenate or 0.27 ng/μL of recombinant human KHK-C protein in 1× assay buffer or negative control into 384 well plate.

-

25.

Add 2.5 μL of 2× substrate solution or negative control immediately using electronic pipette.

-

26.

Cover 384 well plate with microplate sealing film.

-

27.

Spin plate down for 1 min at 650 i (2000 rpm).

-

28.

Incubate for 1 h at 22°C–25°C.

-

29.

Add 5 μL of ADP-Glo reagent to each control and sample wells.

-

30.

Spin plate down at 650 g.

-

31.

Incubate for 40 min at 22°C–25°C.

-

32.

Add 10 μL of developer solution from ADP-Glo assay kit to the control and sample wells.

-

33.

Spin down the plate at 650 g.

-

34.

Incubate for another 40 min at 22°C–25°C in the dark.

-

35.

Read luminescence signal using plate reader.

-

36.

Calculate the relative amount of KHK activity by dividing ADP relative light unit (RLU) by ng of protein and by the time of the reaction. Subtract the background ADP RLU in samples treated with no fructose or 3-O-methyl-d-fructose.

CRITICAL: All processes need to be completed on ice.

Expected outcomes

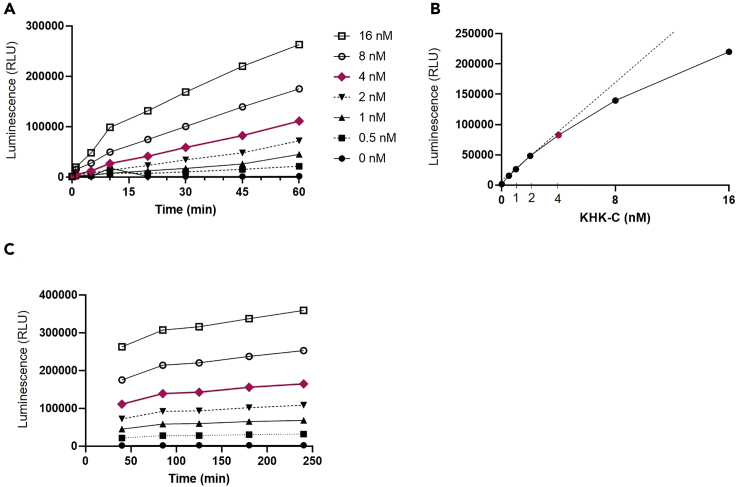

Our protocol provides an experimental method to measure ketohexokinase activity of the recombinant human KHK-C protein and endogenous KHK-C in cell lysates or tissue homogenates. First, we measured KHK-C activity of the recombinant human protein. As expected, KHK-C activity increased with longer incubation time up to 60 min (Figure 1A). Increasing concentrations of human recombinant KHK-C protein up to 16 nM, increased corresponding luminescence readings, indicating higher ADP production and thus greater KHK-C activity (Figure 1A). Next, we measured KHK-C reaction linearity using increasing KHK-C protein concentrations with fixed incubation time. KHK-C concentration of less than 4 nM exhibited near perfect linear increase in the enzymatic activity over time (Figure 1B). Additionally, we measured the signal stability from 45 up to 240 min after adding ADP-Glo detection reagent. For concentrations of KHK less than 4 nM, the assay signal reached stable level after 90 min of incubation and remained stable for four hours (Figure 1C). In summary, reaction incubation time of 60 min and KHK-C protein concentrations of less than 4 nM give the most reliable measurement of KHK-C activity, which remained stable for four hours.

Figure 1.

Concentration and time response of human KHK-C recombinant protein

(A) Progression curves of KHK-C reaction measured at different incubation intervals and with different concentrations of recombinant human KHK-C protein (0–16 nM).

(B) Linearity of ADP production using increasing recombinant KHK-C protein concentrations at fixed reaction time.

(C) Assay signal stability post addition of ADP-Glo detection reagent.

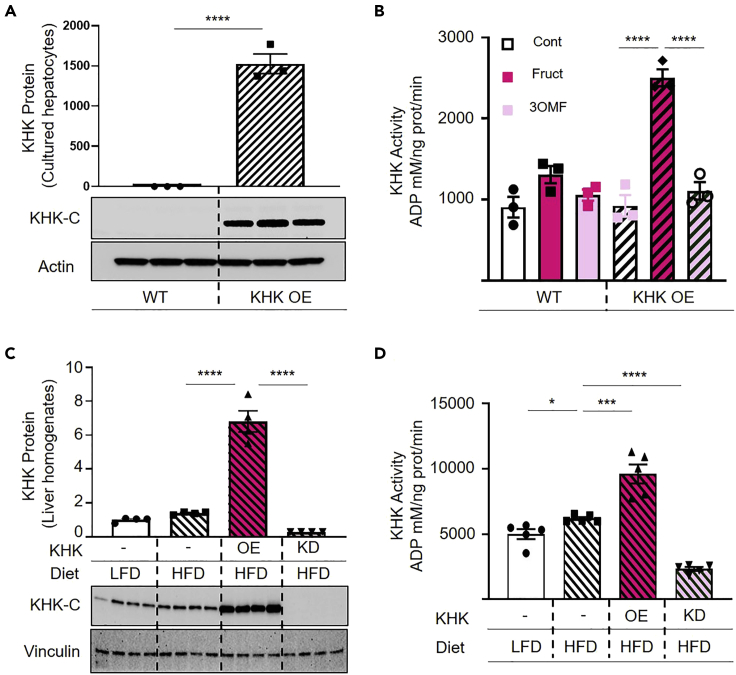

Using the knowledge gained utilizing recombinant human KHK-C protein we determined KHK-C activity in cultured hepatocytes. We have previously reported that immortalized cultured hepatocytes do not express KHK-C and that primary hepatocytes quickly lose KHK-C expression in culture (Softic et al., 2019). This is in agreement with reports indicating that KHK-C is expressed in fully differentiated hepatocytes but not in fetal liver or cancer cells (Li et al., 2016). Thus, we overexpressed (OE) KHK-C in human cultured hepatocytes, HepG2 cells (Figure 2A). Since wild type HepG2 cells completely lack this enzyme, KHK OE hepatocytes had a 1500-fold increase in KHK. However, KHK level in OE cell was similar to that found in liver homogenates (data not shown). Lysates from wild type (WT) and KHK-C OE hepatocytes were added to the substrate solution containing no fructose, 2 mM of fructose or 2 mM of 3-O-methyl-d-fructose (3OMF), a non-metabolizable analog of fructose (Csaky and Fischer, 1984). KHK-C activity was not increased significantly in WT HepG2 hepatocytes when treated with fructose or 3OMF, compared to the controls (Figure 2B). On the other hand, KHK-C activity increased significantly in KHK-C OE hepatocytes treated with fructose, but not with 3OMF. Thus, KHK-C activity was increased only in the cells that possess KHK-C and were treated with fructose as a substrate, indicating that our protocol can reliably measure fructose metabolism via KHK-C.

Figure 2.

KHK-C expression and activity in cell culture and mouse tissue homogenates

(A and B) KHK-C protein (A) and activity (B) levels from WT and KHK-C OE HepG2 cells (n=3). The amount of KHK protein is normalized to actin loading control. KHK activity was measured using no fructose, 2 mM fructose, or 2 mM 3-O-methyl-d-fructose as substrate.

(C and D) KHK protein (C) and activity (D) from liver homogenates of mice fed LFD or HFD with KHK OE and KD. The amount of KHK protein was normalized to vinculin loading control (n=4 and 5).

∗p≤0.05; ∗∗∗p≤0.001; ∗∗∗∗p≤0.0001 via Student’s t-test. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Next, we quantified hepatic KHK-C activity in liver homogenates. Based on the optimal concentration (4 nM or 0.27 ng/uL) of recombinant human KHK-C and some reports indicating that KHK expression in the liver is as high as one percent of the total liver proteome, we prepared 0.025 ug/uL liver lysate concentration. Livers were harvested from mice fed low fat diet (LFD) or high-fat diet (HFD). Mice on HFD were also injected with either AAV to overexpress KHK-C or KHK siRNA to knockdown this protein in the liver. Mice on a HFD did not show a statistically significant increase in KHK-C protein as compared to the mice fed LFD (Figure 2C). Mice on HFD treated with AAV had a three-fold increase in KHK-C protein, whereas KHK siRNA treatment almost completely abrogated KHK protein in the liver (Figure 2C), in agreement with our previous work (Softic et al., 2017). KHK-C activity was significantly higher in mice on HFD as compared to the mice on LFD (Figure 2D). On HFD, OE of KHK-C resulted in doubling of KHK-C activity, whereas KD of KHK decreased KHK activity by 63%. Interestingly, fructose metabolism was not zero in the livers of mice treated with KHK siRNA, suggesting the presence of additional fructose metabolizing enzymes.

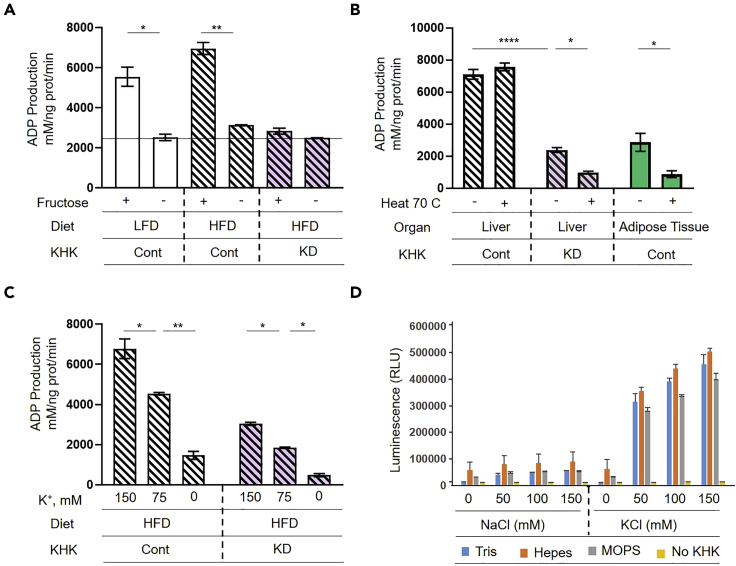

To ensure that the assay is specific for fructose metabolism, we performed several validating experiments. First, we measured ADP production with or without addition of fructose in liver homogenates from the mice on a LFD, HFD and HFD treated with KHK siRNA (Figure 3A). All three samples that did not contain fructose had basal ADP production of about 2000 mM per ng of protein per minute. This represents KHK-independent ADP production and this baseline should be subtracted from the total activity of the samples that do contain fructose. Next, we determined ADP production from the enzymes that are heat stable versus heat liable. This was done in liver homogenates from the mice on a HFD treated with and without KHK siRNA, and in adipose tissue, which is known to metabolize fructose via hexokinase 2. In the livers of control mice, there was no significant difference in ADP production in samples that were heated to 70°C for five minutes and the samples that were not heat treated (Figure 3B). This indicates that most fructose metabolism in the liver occurs via heat stable KHK-C. Mice treated with KHK siRNA had much lower ADP production and this value was further decreased in heated samples. This decrease likely reflects fructose metabolism via hexokinase in KHK siRNA treated livers. Indeed, ADP production in adipose tissue was similar to that from KHK KD livers, and it also decreased following heat treatment. These data indicate that fructose metabolism in adipose tissue and in liver following KHK KD occurs, in part, via heat liable hexokinases.

Figure 3.

Effects of temperature and potassium content on KHK activity

(A) KHK activity was measured in liver homogenates of mice fed LFD and HFD treated with KHK siRNA in the presence or absence of 2 mM fructose.

(B and C) (B) KHK activity after 70°C heat inactivation for 5 min or (C) with different concentrations of potassium.

(D) Activity of recombinant human KHK-C measured in the presence of different concentrations of NaCl and KCl in different buffers (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5; 50 mM Hepes pH7.4 or 50 mM MOPS pH 7.2).

∗p≤0.05; ∗∗∗p≤0.001; and ∗∗∗∗P≤0.0001 via Student’s t-test. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

KHK-C requires potassium for its enzymatic activity and indeed decreasing concentration of potassium in the enzymatic reaction profoundly decreased ADP production (Figure 3C). ADP production is also decreased with decreasing potassium concentrations in the livers of the mice treated with KHK siRNA. Only minimal ADP production was observed in samples that do not contain any potassium, indicating that the contribution of FN3K and other potassium-independent enzymes is minimal in the liver. Since ADP production was profoundly affected by potassium concentrations we further tested how electrolyte composition may affect enzymatic activity of recombinant human KHK-C protein. Indeed, we confirmed that potassium is required for optimal KHK-C activity. Different buffers had minimal effects on KHK-C activity, while Hepes buffer gave the highest reading (Figure 3D).

In summary, utilizing this protocol we can accurately and specifically measure fructose metabolism via KHK-C.

Limitations

Many enzymes utilize ATP and generate ADP to harvest energy for their enzymatic activity. This assay is based on approximating KHK-C activity by measuring ADP accumulation, thus a vast array of enzymes could theoretically confound our results. A reaction mixture not containing fructose or containing 3OMF should be used to subtract background ADP accumulation from the enzymatic reactions that are independent of fructose metabolism. Further, KHK OE and KD samples are useful to ensure that the assay is specific to quantify fructose metabolism via KHK-C.

The distance of the sensor from the sample can affect the intensity of luminescence signal. Since sensor height can be variable, absolute KHK-C activity cannot be compared from one lab to the other.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Luminescence readings are not consistent. Duplicate samples have different readings.

Potential solution

Luminescence signal from neighboring wells may be captured by the sensor. A potential solution is to use a white plate as referenced in this protocol, and not a standard clear plate. Another possibility is to lower the distance between the plate and luminescence reader (Step 35).

Problem 2

KHK-C is not increased in samples that are expected to have high KHK-C activity.

Potential solution

The reaction mixture is sensitive to the amount of protein lysate used in the assay. Please ensure that the protein amount is less than 0.025 ug/uL (Step 22). If more protein is used luminescence readings will be paradoxically lower.

Problem 3

KHK-C activity is too high.

Potential solution

Calcium interacts with the assay and cause high KHK-C activity even when no protein lysate is added. Make sure calcium is not present in the buffers (Step 22).

Problem 4

KHK-C activity is too low.

Potential solution

The position of the sensor has direct effect on the intensity of luminescence. The height of the sensor can be adjusted using auto-adjust function (Step 35).

Problem 5

Fold increase in KHK-C protein is much higher than the percent increase in KHK-C activity.

Potential solution

ADP production from the pathways not related to fructose metabolism can contribute to high background. Normalize the data to the reaction mixtures containing no fructose or 3OMF to calculate fold increase due to fructose metabolism (Step 36).

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Samir Softic at samir.softic@uky.edu.

Materials availability

3-O-methyl-D-fructose (3OMF) has been custom made to validate this protocol. The product has been acquired on a fee-for-service basis from Syngene. We are unable to share the product due to limited amount and high cost associated with custom made products. We have cited the reference used to make this product and have included its NMR spectra, which was not previously published. With this information interested readers can make 3OMF.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate large data sets with a digital object identifier (DOI).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NASPGHAN Foundation Young Investigator Award and COCVD Pilot and Feasibility Grant awarded to SS.

Author contributions

S.-H.P., R.N.H., G.O.M., and J.L. performed experiments and collected the data. All authors contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Declaration of interests

L.N. and H.-C.T. are employees of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc. K.W., G.O.M., and J.B. are employees of AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100731.

Contributor Information

Jianming Liu, Email: jianming.Liu@astrazeneca.com.

Samir Softic, Email: samir.softic@uky.edu.

Supplemental information

References

- Attia S.L., Softic S., Mouzaki M. Evolving role for pharmacotherapy in NAFLD/NASH. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020;14:11–19. doi: 10.1111/cts.12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady R.F. Cyclic acetals of ketoses : Part III. Re-investigation of the synthesis of the isomeric DI-O-isopropylidene-β-d-fructopyranoses. Carbohydrate Res. 1970;15:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Csaky T.Z., Fischer E. Effects of ketohexosemia on the ketohexose transport in the small intestine of rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;772:259–263. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen M., Stankiewicz T.E., Park S.H., Helsley R.N., Chan C.C., Moreno-Fernandez M.E., Doll J.R., Szabo S., Herbert D.R., Softic S., Divanovic S. Non-hematopoietic IL-4Rα expression contributes to fructose-driven obesity and metabolic sequelae. Int J Obes. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00902-6. PMID: 34302121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle C.P., Shires M., Leitch D., Brooke D., Carr I.M., Markham A.F., Hayward B.E., Asipu A., Bonthron D.T. Ketohexokinase: expression and localization of the principal fructose-metabolizing enzyme. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009;57:763–774. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle C.P., Shires M., McRae C., Crellin D., Fisher J., Carr I.M., Markham A.F., Hayward B.E., Asipu A., Bonthron D.T. Both isoforms of ketohexokinase are dispensable for normal growth and development. Physiol. Genomics. 2010;42A:235–243. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00128.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glen W.L., Myers G.S., Grant G.A. Monoalkyl hexoses: improved procedures for the preparation of 1- and 3-methyl ethers of fructose, and of 3-alkyl ethers of glucose. J. Chem. Soc. 1951;672:2568–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Helsley R.N., Moreau F., Gupta M.K., Radulescu A., DeBosch B., Softic S. Tissue-specific fructose metabolism in obesity and diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2020;20:64. doi: 10.1007/s11892-020-01342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Qian X., Peng L.X., Jiang Y., Hawke D.H., Zheng Y., Xia Y., Lee J.H., Cote G., Wang H. A splicing switch from ketohexokinase-C to ketohexokinase-A drives hepatocellular carcinoma formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:561–571. doi: 10.1038/ncb3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaisse W.J., Malaisse-Lagae F., Davies D.R., Van Schaftingen E. Presence of fructokinase in pancreatic islets. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sener A., Giroix M.H., Malaisse W.J. Hexose metabolism in pancreatic islets. The phosphorylation of fructose. Eur. J. Biochem. 1984;144:223–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S., Cohen D.E., Kahn C.R. Role of dietary fructose and hepatic de novo lipogenesis in fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016;61:1282–1293. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S., Gupta M.K., Wang G.X., Fujisaka S., O'Neill B.T., Rao T.N., Willoughby J., Harbison C., Fitzgerald K., Ilkayeva O. Divergent effects of glucose and fructose on hepatic lipogenesis and insulin signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:4059–4074. doi: 10.1172/JCI94585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S., Meyer J.G., Wang G.X., Gupta M.K., Batista T.M., Lauritzen H., Fujisaka S., Serra D., Herrero L., Willoughby J. Dietary sugars alter hepatic fatty acid oxidation via transcriptional and post-translational modifications of mitochondrial proteins. Cell Metab. 2019;30:735–753 e734. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softic S., Stanhope K.L., Boucher J., Divanovic S., Lanaspa M.A., Johnson R.J., Kahn C.R. Fructose and hepatic insulin resistance. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2019.1711360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szwergold B.S., Howell S., Beisswenger P.J. Human fructosamine-3-kinase: purification, sequencing, substrate specificity, and evidence of activity in vivo. Diabetes. 2001;50:2139–2147. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.9.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate large data sets with a digital object identifier (DOI).