Summary

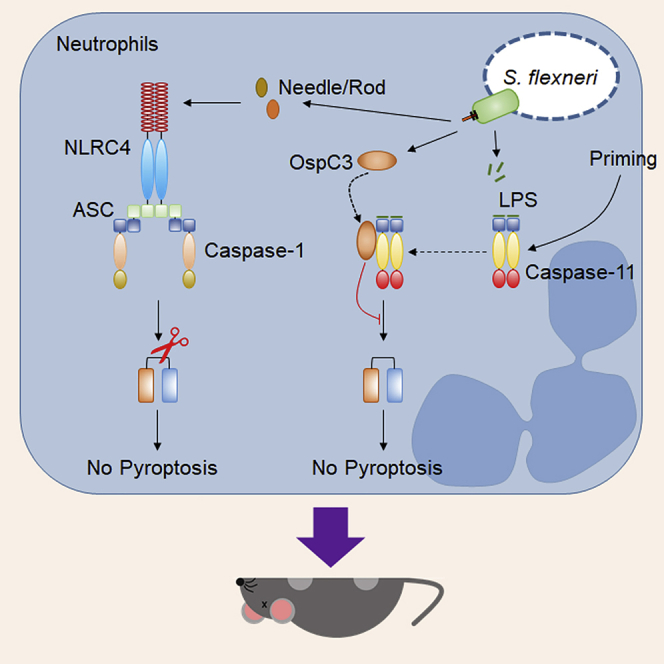

Shigella flexneri, a cytosol-invasive gram-negative pathogen, deploys an array of type III-secreted effector proteins to evade host cell defenses. Caspase-11 and its human ortholog caspase-4 detect cytosolic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and trigger gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis to eliminate intra-cytoplasmic bacterial threats. However, the role of caspase-11 in combating S. flexneri is unclear. The Shigella T3SS effector OspC3 reportedly suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by inhibiting caspase-4 but not caspase-11 activity. Surprisingly, we found that S. flexneri also uses OspC3 to inhibit murine caspase-11 activity. Mechanistically, we found that OspC3 binds only to primed caspase-11. Importantly, we demonstrate that S. flexneri employs OspC3 to prevent caspase-11-mediated pyroptosis in neutrophils, enabling bacteria to disseminate and evade clearance following intraperitoneal challenge. In contrast, S. flexneri lacking OspC3 is attenuated in a caspase-11- and gasdermin D-dependent fashion. Overall, our study reveals that OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS detection in a broad array of mammals.

Subject areas: Immunology, Microbiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

S. flexneri T3SS-secreted OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by caspase-11

-

•

OspC3 binds to caspase-11 in a priming-dependent manner

-

•

S. flexneri employs OspC3 to prevent caspase-11-mediated pyroptosis in neutrophils

-

•

Neutrophil caspase-11 is essential in defense against S. flexneri ΔOspC3 in vivo

Immunology; Microbiology

Introduction

The host cytosol is a nutrient-rich environment that can be an ideal niche for pathogen replication (Ray et al., 2009). However, the cytosol is also heavily guarded by several innate immune mechanisms, including cell autonomous responses mediated by interferon-stimulated genes including guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs) and inflammasome responses mediated by NOD-like receptors (NLRs) and inflammatory caspases (caspase-1 and -11) (Oh et al., 2020; Randow et al., 2013). Due to these host defenses, few pathogens succeed in adopting the cytosol as a replication niche.

Inflammasomes monitor the cytosol for signs of infection, such as secreted pathogen products. The NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome detects the activity of virulence-associated bacterial type III secretion systems (T3SSs), alerting the cell to potential hijacking of cellular machinery by the pathogen (Franchi et al., 2006; Miao et al., 2006; Molofsky et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2006). In addition, caspase-11 monitors the cytosol for pathogen products by directly sensing bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Aachoui et al., 2013; Hagar et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2013). Caspase-11 is duplicated in humans as caspase-4 and -5, which both detect cytosolic LPS (Kajiwara et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2014). The NLRP3 inflammasome senses cytosolic perturbations indicative of catastrophic cellular events such as membrane pore formation or mitochondrial dysfunction (Swanson et al., 2019). Upon detection, NAIP/NLRC4 and NLRP3 signal to caspase-1, whereas caspase-11 initiates its own oligomerization and auto-activation (Oh et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2014). Regardless of the activating sensors, both caspases cleave and activate the pore-forming protein gasdermin D, resulting in pyroptosis (He et al., 2015; Kayagaki et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015). Additionally, caspase-1 cleaves and activates the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 (Ramirez et al., 2018).

Shigella spp. is a cytosol-invasive pathogen that causes acute diarrhea and bacillary dysentery. Although the disease is usually self-limiting, infection can lead to severe morbidity and mortality, especially among children <5 years old. S. flexneri, a model member of the genus, requires a T3SS and at least 30 secreted effectors and virulence factors to cause disease (Galán et al., 2014; Schnupf and Sansonetti, 2019). These factors are often functionally redundant but are required to invade host cells, maintain a replicative niche, minimize alarm signals, and promote colonization (Schnupf and Sansonetti, 2019). Following uptake by a host cell, S. flexneri escapes from the initial phagosome, eliciting caspase-1 activation and pyroptotic cell death following recognition of T3SS rod and needle proteins (MxiI and MxiH, respectively) by the NLRC4 inflammasome (Suzuki et al., 2007). However, it is still unclear if S. flexneri vacuolar escape to the cytosol triggers caspase-11-directed pyroptosis. A study by Kobayashi et al. showed that S. flexneri is detected by caspase-4 that triggers pyroptosis and is counteracted by a Shigella T3SS virulence factor OspC3 (Kobayashi et al., 2013). In contrast, a recent study by Russo et al. showed that S. flexneri triggers cell death exclusively through caspase-11 (Russo et al., 2021). To address this dichotomy, Kobayashi et al. demonstrated that OspC3 binds specifically to the human caspase-4-p19 catalytic subunit in epithelial cells to inhibit its activation following LPS detection (Kobayashi et al., 2013). In contrast, OspC3 does not bind to the catalytic domain of caspase-11, suggesting the effector does not block caspase activity (Kobayashi et al., 2013). Interestingly, Wandel et al. found that Casp11−/− mice are susceptible to infection by S. flexneri lacking OspC3, whereas wild-type mice are resistant using an in vivo intraperitoneal infection model, suggesting OspC3 suppresses caspase-11 activity (Wandel et al., 2020). Thus, it is still unclear if OspC3 blocks murine LPS sensing by caspase-11 and whether direct binding between caspase-11 and OspC3 is required.

It has long been proposed that pyroptosis is beneficial for S. flexneri and allows the pathogen to escape macrophages and infect epithelial cells from the basolateral side of the gastrointestinal tract (Ashida et al., 2014; Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2010; Schnupf and Sansonetti, 2019). In this scenario, it is unclear why S. flexneri activates caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis yet evades LPS sensing. Pyroptosis is a powerful defense mechanism against many intracellular pathogens (Aachoui et al., 2013; Miao et al., 2010). Either caspase-1 or caspase-11 can cleave gasdermin D to eliminate bacteria by preventing establishment of an intracellular niche and subsequently trapping bacteria in pore-induced intracellular traps for efferocytosis and elimination by neutrophils (Jorgensen et al., 2016). Neutrophils are competent for inflammasome activation (Chen et al., 2020), which is critical during resolution of cytosol-invasive pathogen infection (Chen et al., 2018; Kovacs et al., 2020). We and others found that in neutrophils, caspase-1 activation triggers only IL-1β secretion but not cell death. In contrast, neutrophil caspase-11 detects cytosol-invasive pathogens including Burkholderia thailandensis, Salmonella Typhimurium lacking SifA, and Citrobacter rodentium, triggering gasdermin D-driven pyroptosis and extrusion of antimicrobial NETs to eliminate bacteria (Chen et al., 2018; Kovacs et al., 2020). However, neutrophils enhance S. flexneri adhesion and invasion of epithelial cells (Eilers et al., 2010). Thus, the beneficial effects of gasdermin D-mediated cell death for the host during S. flexneri infection are not well defined.

In this study, we assessed whether S. flexneri evades murine neutrophil-mediated caspase-11 pyroptosis in an OspC3-dependent fashion. We show that S. flexneri activates gasdermin D through caspase-1 but evades caspase-11 responses in macrophages and neutrophils. We demonstrate that the S. flexneri T3SS effector OspC3 binds to primed caspase-11 to inhibit cytosolic LPS sensing. Using an intraperitoneal model of infection, we demonstrate that S. flexneri uses OspC3 to suppress caspase-11 activity, particularly in neutrophils, enabling bacteria to disseminate and evade clearance. Consequently, S. flexneri lacking OspC3 is attenuated in a caspase-11- and gasdermin D-dependent fashion.

Results

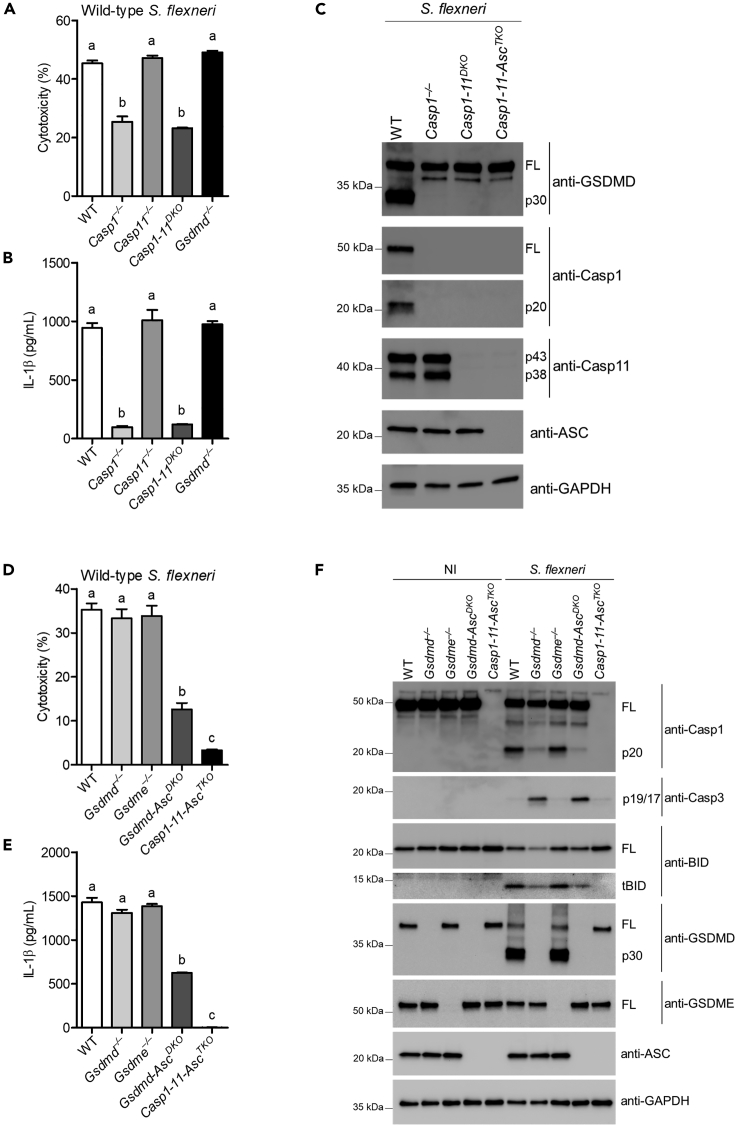

S. flexneri activates the gasdermin D response through caspase-1 but not caspase-11

S. flexneri, a hexa-acylated lipid A-expressing bacterium, invades host cells and uses its T3SS to rapidly escape a phagosomal vacuole to establish a replicative niche within the cytosol. Caspase-11 and its human orthologs caspase-4 and -5 detect cytosolic LPS and trigger gasdermin D-dependent pyroptosis to eliminate intra-cytoplasmic bacterial threats (Oh et al., 2020). However, the role of caspase-11 in S. flexneri defense is still unclear. Because the S. flexneri T3SS effector OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by inhibiting caspase-4 but does not bind murine caspase-11, we hypothesized that S. flexneri is detected by caspase-11. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed the macrophage response to S. flexneri. Our results show that S. flexneri-induced lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and IL-1β release were largely dependent on caspase-1 in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) (Figures 1A and 1B). Consistent with these results, cleavage of the pyroptotic substrate gasdermin D was driven by caspase-1 (Figure 1C) (Kovacs et al., 2020), suggesting S. flexneri is not detected by caspase-11. BMM infection with S. flexneri strain BS103, which lacks the virulence plasmid, results in neither caspase-1- nor caspase-11-driven cell death (Figure S1A). Both NLRC4 and NLRP3 detected S. flexneri, accounting for the majority of IL-1β secretion and pyroptosis (Figures S1B and S1C). Although caspase-1 promotes a robust gasdermin D cleavage response to induce pyroptosis, we also observed high levels of cytotoxicity and IL-1β release in Gsdmd–/– BMMs infected with S. flexneri. However, this response was significantly reduced in Gsdmd-AscDKO BMMs and disappeared in Casp1-11-AscTKO cells (Figures 1D and 1E). These results are consistent with reports that show gasdermin D deficiency only delays cell lysis and that bypass pathways branching from ASC to caspase-8/-3 or branching at caspase-1 to BID/caspase-9/-3 control alternative cell death pathways (Aizawa et al., 2020; Heilig et al., 2020; Tsuchiya et al., 2019) (Figure S1D). In accordance, S. flexneri triggered processing of BID and caspase-3 to their active forms in either an ASC- or caspase-1-dependent manner (Figure 1F). Because active caspase-3 could potentially trigger cell lysis indirectly via apoptosis followed by secondary necrosis or directly by cleaving gasdermin E to promote pyroptosis (Heilig et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018), we examined the susceptibility of Gsdme–/– BMMs to S. flexneri infection. Our results showed that gasdermin E was dispensable for cell death in wild-type BMMs (Figures 1D–1F), excluding gasdermin E as the primary mediator of cell death in response to S. flexneri infection. However, this finding does not exclude the possibility that gasdermin E could trigger cell death in the absence of gasdermin D. Collectively, these results indicate that S. flexneri activates a caspase-1 canonical inflammasome but evades caspase-11 in macrophages.

Figure 1.

S. flexneri activates the gasdermin D response through caspase-1 but evades the caspase-11 response

(A–F) Indicated BMMs were primed with LPS (50 ng/mL) overnight and subsequently infected with S. flexneri (MOI 50) for 4 hr. Extracellular bacteria were eliminated by adding gentamicin (100 μg/mL) 1 hr after infection. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay (A and D), and IL-1β release was determined by ELISA (B and E). Western blots were probed with the indicated antibodies (C and F). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Bar represents mean ± SEM. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Cytotoxicity and IL-1β levels were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different from each other, p ≤ 0.05.

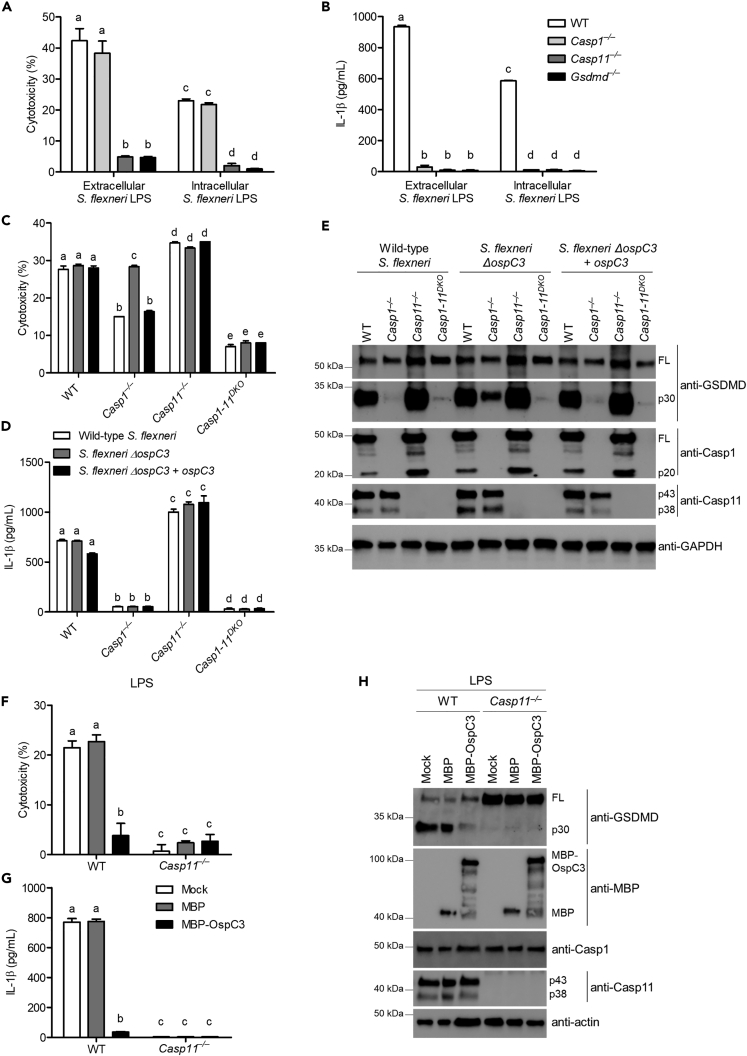

S. flexneri OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by caspase-11

Next, we examined S. flexneri evasion of caspase-11 activity. We hypothesized that S. flexneri evades caspase-11 by modifying its LPS structure. We compared S. flexneri grown in tryptic soy broth (extracellular) to S. flexneri recovered from infected Casp1-11DKO (intracellular). Lysates from intracellular and extracellular S. flexneri cultures were boiled and digested with RNase, DNase, and proteinase K to eliminate canonical inflammasome agonists, and then, BMMs were transfected with individual samples (Hagar et al., 2013). We previously used this approach to identify cytosolic LPS as a caspase-11 agonist (Hagar et al., 2013). In response to each lysate, wild-type and Casp1−/− BMMs underwent pyroptosis dependent on caspase-11 (Figures 2A and 2B), suggesting in macrophages at these time points; S. flexneri does not modify its LPS structure to evade detection. While LPS modification was shown previously in human epithelial cells (Paciello et al., 2013), our results suggest a similar modification that cannot be quickly accomplished within a single infected cell, leaving bacteria at risk for cytosolic LPS detection via caspase-11.

Figure 2.

S. flexneri OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by caspase-11

(A and B) Lysates from intracellular and extracellular S. flexneri were boiled and digested with RNase, DNase, and proteinase K to eliminate canonical inflammasome agonists. LPS-primed BMMs were transfected with lysates prepared from extracellular or intracellular S. flexneri for 4 hr. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay (A), and IL-1β release was determined by ELISA (B).

(C–E) LPS-primed BMMs were infected with wild-type S. flexneri, ΔospC3, or ΔospC3 + ospC3 complementation (MOI 50) for 4 hr. Extracellular bacteria were eliminated by adding gentamicin (100 μg/mL) 1 hr after infection. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay (C), and IL-1β release was determined by ELISA (D). Gasdermin D, caspase-1, and caspase-11 cleavage were detected by western blot (E). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

(F–H) LPS-primed BMMs were transfected or not with MBP or MBP-OspC3 for 4 hr, followed by stimulation with 5 μg/mL LPS for 4 hr. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay (F), and IL-1β release was determined by ELISA (G). Gasdermin D cleavage, caspase-1, caspase-11, and MBP or MBP-OspC3 expression were determined by western blot (H). Actin was used as a loading control.

Bar represents mean ± SEM. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Cytotoxicity and IL-1β levels were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different from each other, p ≤ 0.05.

Shigella OspC3 binds to human caspase-4 and inhibits its activity (Kobayashi et al., 2013). However, Kobayashi et al. indicated that OspC3 failed to bind the murine ortholog caspase-11. Nevertheless, given our data showing that murine caspase-11 does not detect S. flexneri, we tested whether S. flexneri also uses OspC3 to suppress murine cytosolic LPS sensing by caspase-11. Analysis of BMMs infected with wild-type S. flexneri confirmed that gasdermin D cleavage and the resulting pyroptosis were largely dependent on caspase-1 with no contribution from caspase-11. Surprisingly, OspC3-deficient S. flexneri activated both caspase-1 and -11, resulting in gasdermin D cleavage, secretion of IL-1β, and LDH release (Figures 2C–2E). It is worth noting that although we did not observe substantial cleavage of caspase-11 by western blot (caspase-11 is detected as two bands representing two isoforms after priming), we have historically found detection of caspase-11 cleavage by western blot to be an unreliable method to evaluate activation compared to downstream effects such as pyroptosis or gasdermin D cleavage (Hagar et al., 2013). Complementation of OspC3 mutant bacteria with a plasmid that expresses ospC3 restored inhibition of caspase-11 as demonstrated by lack of gasdermin D cleavage and LDH release in Casp1−/− BMMs (Figures 2C–2E).

Next, we examined whether OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by caspase-11. Primed wild-type or inflammasome-deficient BMMs were transfected with either maltose binding protein-OspC3 (MBP-OspC3) or MBP alone, followed by LPS transfection. Our results showed that macrophages transfected with MBP alone followed by cytosolic LPS stimulation activated the caspase-11 non-canonical inflammasome as evidenced by increased gasdermin D cleavage, and LDH and IL-1β release (Figures 2F–2H). In contrast, caspase-11-dependent gasdermin D cleavage, IL-1β release, and pyroptosis were substantially suppressed when wild-type macrophages were transfected with MBP-OspC3 (Figures 2F–2H). MBP-OspC3 did not affect caspase-1 activation mediated by the AIM2 inflammasome following poly(dA:dT) transfection (Figure S2), confirming the specificity of OspC3 function for the LPS sensing signaling pathway. These results indicate that S. flexneri uses OspC3 to inhibit murine caspase-11 sensing of cytosolic LPS in macrophages.

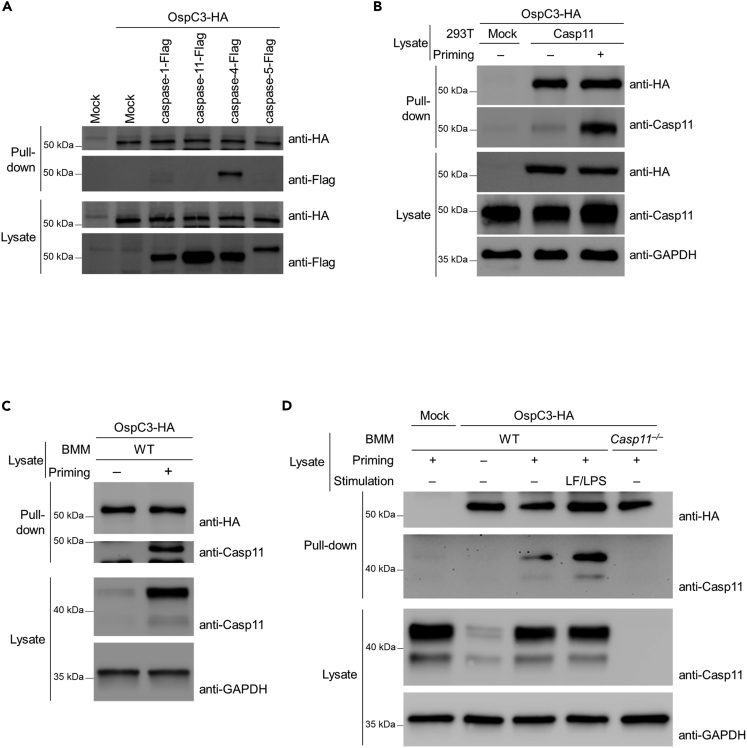

OspC3 inhibits primed caspase-11 activity

OspC3 reportedly binds to caspase-4 but not caspase-5 or -11 (Kobayashi et al., 2013). Specifically, Kobayashi et al. showed that OspC3 binds to the catalytic domain of caspase-4 to prevent hetero-dimerization of caspase-4-p19 and caspase-4-p10. This event attenuated caspase-4-mediated cell death (Kobayashi et al., 2013). Our results indicate that OspC3 also modulates caspase-11 activity, leading us to examine how this inhibition is mediated. We first re-tested OspC3 binding to murine caspase-11 and its human orthologs, caspase-4 and -5. We performed pull-down assays with OspC3-HA using lysates of HEK293T cells expressing caspase-1-Flag, caspase-11-Flag, caspase-4-Flag, or caspase-5-Flag. Caspase-4, but not caspase-5, murine caspase-1, or caspase-11, bound to OspC3, confirming prior findings (Figure 3A) (Kobayashi et al., 2013). In addition, OspC3-HA did not elicit proteasome- or autophagy-mediated caspase-11 degradation (Figure S3A). Caspase-11 and caspase-4 directly bind to LPS and oligomerize to form the non-canonical inflammasomes (Shi et al., 2014). Unlike caspase-4, caspase-11 requires priming through IFN-induced JAK-STAT signaling (Aachoui et al., 2013, 2015; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Hagar et al., 2013; Rathinam et al., 2012). The mechanism by which IFNs prime caspase-11 has not been completely defined. While transcriptional induction of caspase-11 is one aspect of priming, it is unclear if transcriptional control is sufficient for priming. Here, we investigated whether primed caspase-11 binds to OspC3. To test this hypothesis, HEK293T cells over-expressing caspase-11 were primed with IFN-γ. Thereafter, cell lysates were prepared from each experimental group and used in pull-down assays with OspC3-HA as above. Interestingly, under these conditions, caspase-11 bound to OspC3-HA (Figure 3B). To further confirm that priming enables endogenous caspase-11 binding to OspC3, wild-type or Casp11−/− BMMs were primed and subsequently transfected with LPS to activate caspase-11. Consistent with previous reports, priming significantly up-regulated caspase-11 expression in BMMs (Figure S3B). Therefore, basal expression of caspase-11 in unprimed macrophages was not sufficient to bind OspC3 (Figure 3C). In contrast, primed BMMs had increased caspase-11 expression, and under these conditions, caspase-11 bound OspC3-HA. Furthermore, significantly increased binding between caspase-11 and OspC3 occurred when primed macrophages were further stimulated with cytosolic LPS (Figures 3D and S3C), suggesting OspC3 can regulate caspase-11 activity after detection of cytosolic LPS.

Figure 3.

OspC3 binds to primed caspase-11, suppressing its activity

(A–D) HA-conjugated beads were incubated with lysates from HEK293T cells expressing OspC3-HA. HA-conjugated beads bound to OspC3-HA were mixed with lysates from HEK293T cell expressing the indicated caspases (A), with mock or lysates from caspase-11-expressing HEK293T cells IFN-γ (50 ng/mL) primed for 4 hr or not (B), with BMM lysates LPS primed or not (C), or with lysates from BMMs transfected with LPS (5 μg/mL) for 4 hr to activate the non-canonical inflammasome following IFN-γ priming or not (D). Western blots were probed with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

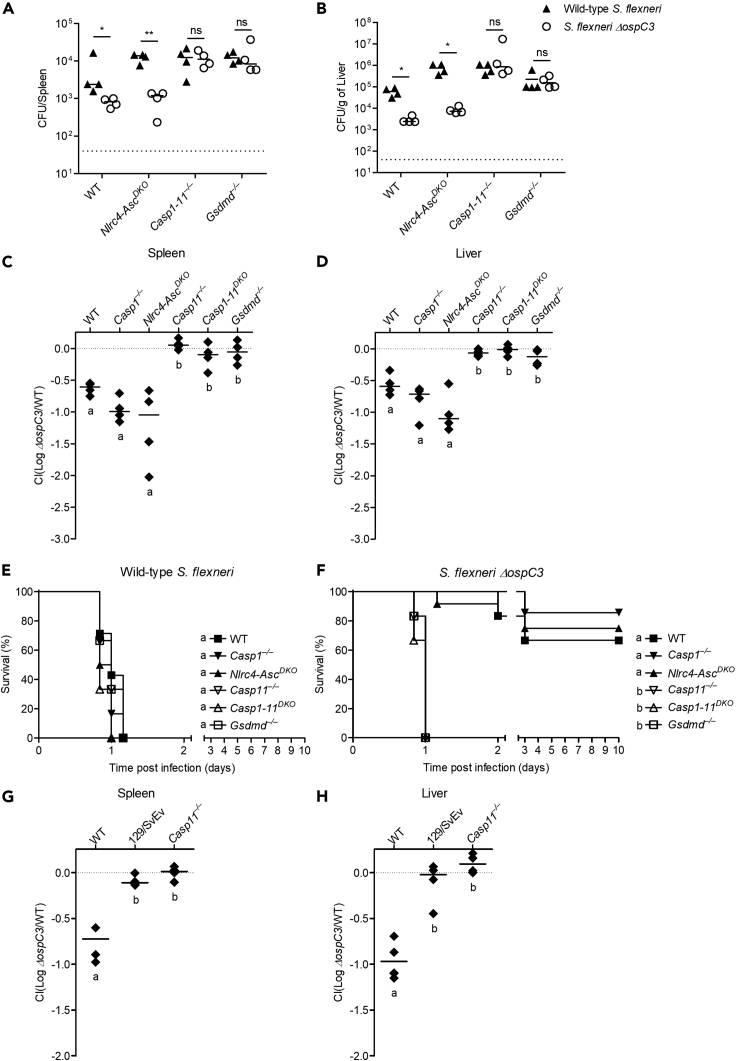

Caspase-11 is essential to defend against S. flexneri lacking OspC3

Pyroptosis is a powerful defense mechanism against intracellular pathogens that is triggered independently by caspase-1 or caspase-11, suggesting loss or evasion of either caspase would lead to reduced cell death (Aachoui et al., 2013; Miao et al., 2010). However, we previously found that caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis plays only a minor role in vivo and cannot substitute for caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis during cytosol invasive pathogen infection (Aachoui et al., 2015). Therefore, we examined the in vivo importance of OspC3 inhibition of caspase-11 sensing of S. flexneri. We used intraperitoneal infection to determine the role of caspase-1 and -11 and gasdermin D during host defense as this route was previously used to identify the function of S. flexneri virulence factors (Li et al., 2017). Although we showed that S. flexneri is detected by macrophage caspase-1 in vitro but evades caspase-11, wild-type, Casp1-11DKO or Gsdmd–/– mice were similarly susceptible to various doses of S. flexneri (Figure S4A). At lower dose, Casp1-11DKO and Gsdmd−/− had detectable bacterial loads, and at higher doses, all mice had similarly elevated pathogen burdens. Therefore, our data suggest the caspase-1-driven response is dispensable to counter S. flexneri virulence during intraperitoneal challenge. Next, we examined the importance of OspC3 suppression of caspase-11 activity during S. flexneri systemic infection. However, wild-type S. flexneri-infected wild-type mice had high bacterial loads in the spleen and liver, and mice infected with S. flexneri ΔospC3 had significantly lower burdens (Figures 4A and 4B), demonstrating the importance of OspC3 in vivo. This dependence on OspC3 was replicated in Nlrc4-AscDKO mice (equivalent to caspase-1-deficent mice). However, when caspase-11 or gasdermin D were absent in Casp1-11DKO and Gsdmd–/– mice, respectively, the OspC3-mediated inhibitory phenotype disappeared (Figures 4A and 4B). To further quantify these differences, we determined relative clearance of S. flexneri ΔospC3 during co-infection with wild-type S. flexneri. We recovered between 5 and 10 times as much wild-type S. flexneri as S. flexneri ΔospC3 from the spleen and liver of wild-type, Casp1−/−, and Nlrc4-AscDKO mice; however, this effect was lost in Casp11−/−, Casp1-11DKO, and Gsdmd–/– mice where we recovered similar numbers of both strains (Figures 4C, 4D, S4B, and S4C). Likewise, lethal challenge studies revealed that wild-type and all inflammasome-deficient mice tested were susceptible and succumbed to a high dose challenge (7.5 × 107 CFU) of wild-type S. flexneri (Figure 4E). This finding is consistent with a model in which OspC3 inhibits caspase-11; thus, deleting murine casp11 has no effect. In contrast, when infected with the same inoculum of S. flexneri ΔospC3, the majority of wild-type, Casp1−/−, Nlrc4-AscDKO mice survived, whereas Casp11−/−, Casp1-11DKO, and Gsdmd–/– mice were extremely susceptible and succumbed to S. flexneri ΔospC3 infection (Figure 4F). Collectively, these results indicate the caspase-11-gasdermin D axis is essential to defend against S. flexneri lacking OspC3.

Figure 4.

Caspase-11 is essential in defense against S. flexneri lacking OspC3 in vivo

(A and B) Indicated mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 107 CFU of S. flexneri wild-type or ΔospC3 and bacterial loads in the spleen (A) and liver (B) were determined 24 hr after infection.

(C, D, G, and H) Indicated mice were co-infected i.p. with 2.5 × 107 CFU of both wild-type S. flexneri and S. flexneri ΔospC3 encoding ampicillin or kanamycin resistance, respectively. Bacterial loads from co-infected mice were determined 24 hr after infection and competitive index calculated (CI = log (S. flexneri ΔospC3/S. flexneri wild type)) in spleen (C and G) and liver (D and H).

(E and F) Indicated mice were infected i.p. with 7.5 × 107 CFU of S. flexneri wild type or ΔospC3, and survival was monitored twice per day for 10 days.

Data are representative of three experiments. Bar represents mean. Dashed line in (A and B) indicates limit of detection and in (C, D, G, and H) represents the x axis. For bacterial burdens (A and B), statistical significance was assessed by two-tailed Student's t-test (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ns: not significant). For competitive index (C, D, G, and H), statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. Survival curves were compared using log rank (Mantel-Cox) test with Bonferroni-corrected threshold for statistical significance of p ≤ 0.003 (E, F). Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different from each other.

We next considered whether Nramp1 deficiency is involved in the extreme susceptibility of Casp11−/− mice. Nramp1-sufficient 129/SvEv mice are naturally defective in caspase-11 due to a passenger mutation (Kayagaki et al., 2011). Concordant with our results in Casp11−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background, we again obtained similar numbers of wild-type S. flexneri as S. flexneri ΔospC3 from the spleen and liver of the naturally Casp11mt/mt 129/SvEv mice (Figures 4G, 4H and S4D, and S4E). This phenotype is consistent with a dominant role for caspase-11 in defense against cytosol invasive pathogens.

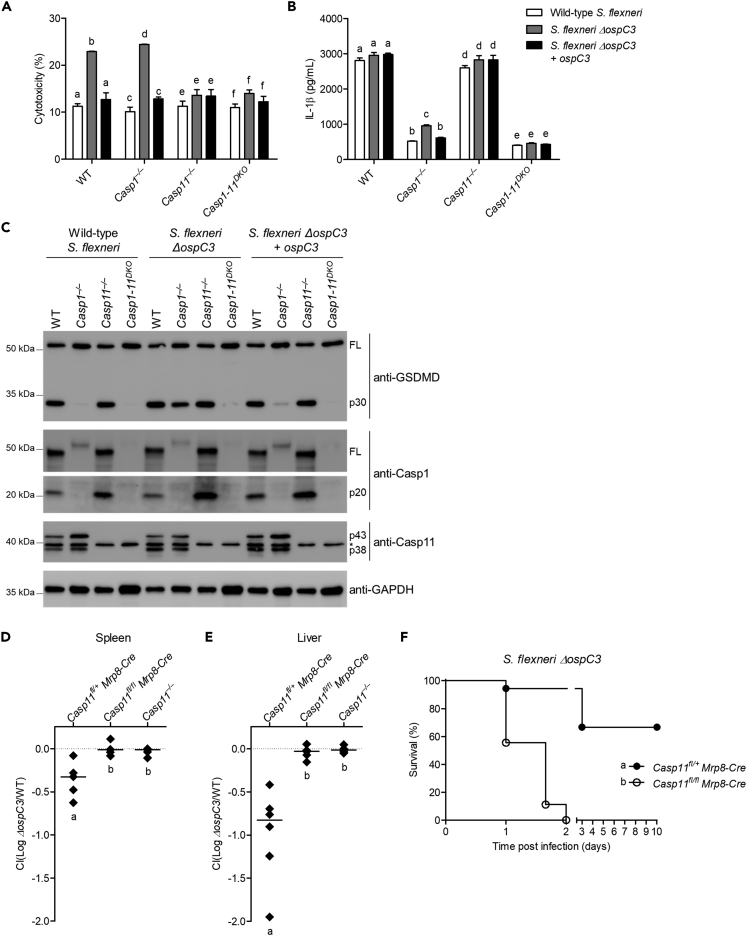

S. flexneri deploys OspC3 to suppress neutrophil caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis and bacterial clearance

Next, we examined why OspC3-mediated suppression of LPS sensing by caspase-11 is beneficial to S. flexneri despite the caspase-1-directed inflammasome response to T3SS activity. We and others demonstrated that in neutrophils, caspase-1 and caspase-11 activation leads to gasdermin D cleavage (Chen et al., 2018; Karmakar et al., 2020; Kovacs et al., 2020). However, only caspase-11 activation led to pyroptosis necessary for clearance of the cytosol-invasive pathogens B. thailandensis and S. Typhimurium ΔsifA (Chen et al., 2018; Kovacs et al., 2020). Neutrophils play an important role during shigellosis (reviewed (Hermansson et al., 2016)), but the specific role of the neutrophil inflammasome remains understudied. Therefore, we reasoned that the ability of S. flexneri to inhibit caspase-11 activation which would specifically open neutrophils as an infectable cell type because caspase-1 does not trigger neutrophil gasdermin D-dependent pyroptosis. To examine this hypothesis, we first infected neutrophils from wild-type, Casp1−/−, Casp11−/−, or Casp1-11DKO mice with either wild-type S. flexneri, S. flexneri ΔospC3, or ospC3-complemented S. flexneri ΔospC3. Wild-type S. flexneri promoted gasdermin D cleavage and IL-1β release that required caspase-1; however, no LDH was released, consistent with neutrophil resistance to caspase-1-driven gasdermin D cleavage (Figures 5A–5C). In contrast, S. flexneri ΔospC3 triggered comparable gasdermin D cleavage in wild-type, Casp1−/−, and Casp11−/− neutrophils, and additionally triggered lytic cell death in wild-type and Casp1−/− neutrophils consistent with caspase-11 activation in neutrophils (Figures 5A–5C). Complementation of these mutants with a plasmid expressing ospC3 restored inhibition of caspase-11 resulting in gasdermin D cleavage and IL-1β release but not LDH release in wild-type and Casp11−/− neutrophils (Figures 5A–5C). These results indicate that S. flexneri triggers caspase-1 activation to promote IL-1β maturation but does not elicit pyroptosis. Second, S. flexneri OspC3 suppresses caspase-11 detection and subsequent pyroptosis in neutrophils.

Figure 5.

S. flexneri deploys OspC3 to suppress neutrophil caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis and bacterial clearance

(A–C) Pam3CSK4-primed neutrophils were infected with wild-type S. flexneri or S. flexneri ΔospC3 (MOI 100) for 4 hr. Cytotoxicity was determined by LDH release assay (A), IL-1β was determined by ELISA (B) and gasdermin D, caspase-1, and caspase-11 cleavage were detected by western blot (C). GAPDH was used as a loading control. The asterisk indicates a non-specific band.

(D and E) Indicated mice were infected i.p. with 2.5 × 107 CFU of both wild-type S. flexneri and S. flexneri ΔospC3 encoding ampicillin or kanamycin resistance, respectively. Bacterial loads from co-infected mice were determined 24 hr after infection and used to determine competitive index in the spleen (D) and liver (E).

(F) Indicated mice were infected i.p. with 7.5 × 107 CFU of S. flexneri wild type or ΔospC3 and survival was monitored.

Data are representative of three experiments. Bar represents mean ± SEM in (A-B and D-E). Dashed line in (D and E) indicates the x axis. For cytotoxicity and IL-1β levels (A, B), statistical significance was assessed two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. For competitive index (D, E), statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. Survival curves were compared using log rank (Mantel-Cox) to determine the p value (F). Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different from each other, p ≤ 0.05.

We next questioned the in vivo role of the neutrophil caspase-11 inflammasome in defending against S. flexneri. We recently used Casp11fl/flMrp8-cre mice to examine the importance of neutrophil caspase-11 during B. thailandensis clearance in vivo (Kovacs et al., 2020). Mrp8-cre deletes floxed genes at 80% efficiency in splenic, peripheral blood, and bone marrow neutrophils, while deleting at 0%–20% efficiency in monocytes and macrophages (Abram et al., 2014). We demonstrated that having 20% caspase-11 deficiency in a hematopoietic compartment is not sufficientt for susceptibility, suggesting the immune system can overcome a relatively small fraction of susceptible cells that harbor infectious agents (Kovacs et al., 2020). Therefore, we returned to these mice to study relative clearance of S. flexneri ΔospC3 during co-infection with wild-type S. flexneri. As before, we recovered ~5 times as much wild-type S. flexneri as S. flexneri ΔospC3 in the spleen and liver of caspase-11-sufficient mice (Casp11fl/+Mrp8-cre). In contrast, there was no difference in clearance of wild-type S. flexneri and S. flexneri ΔospC3 during co-infection in Casp11fl/flMrp8-cre mice or Casp11 whole-body knockout mice (Figures 5D, 5E, S5A, and S5B). Consistent with these results, a lethal challenge study showed that Casp11fl/flMrp-cre mice succumbed rapidly (2 days) to S. flexneri ΔospC3 infection with similar kinetics to Casp11 whole-body knockout mice, whereas the majority of Casp11fl/+Mrp-cre mice survived S. flexneri ΔospC3 infection (Figure 5F). Together, these results suggest the neutrophil caspase-11 inflammasome response is critical for defending against S. flexneri and demonstrate a role for the Shigella effector OspC3 in subverting this sensing/clearance mechanism.

Discussion

In human cells, S. flexneri subverts LPS-induced intracellular signaling by either directly interacting with caspase-4 to inhibit its activity or under-acetylating its LPS structure to evade detection by caspase-4 (Kobayashi et al., 2013; Paciello et al., 2013). Here, we found that S. flexneri also employs the T3SS effector OspC3 to inhibit cytosolic LPS sensing by its murine ortholog, caspase-11, indicating OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS detection in a broad array of mammals. Previously, Kobayashi et al. showed that OspC3 binds to the catalytic domain of caspase-4 but not caspase-11 to prevent hetero-dimerization of caspase-4-p19 and caspase-4-p10 subunits (Kobayashi et al., 2013). In contrast, we found that OspC3 binds to caspase-11 only when primed through JAK-STAT or TLR signaling. This binding is enhanced when caspase-11 detects cytosolic LPS. Caspase-11 must be primed by type I or II IFN to detect cytosolic LPS (Aachoui et al., 2013, 2015; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Hagar et al., 2013; Rathinam et al., 2012), and we demonstrate priming is also critical for OspC3 suppression of caspase activity. However, the nature of priming events that promote caspase-11 activation and/or suppression by OspC3 remains unknown. Previous studies suggested that in addition to upregulation of caspase-11 expression, priming induces GBPs to promote assembly of the non-canonical inflammasome (Kutsch et al., 2020; Santos et al., 2020; Wandel et al., 2020). However, a recent study by Brubaker et al. found that induction of GBPs does not fully account for the effect of priming on LPS sensing and suggested priming triggers unknown factors that regulate caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis (Brubaker et al., 2020). In our study, the nature of this unknown factor or event appears to be conserved between human and murine systems as we could replicate the priming effects in primary macrophages and a caspase-11-overexpressing human embryonic kidney 293T cell line. We speculate that priming likely introduces a post-translational modification and/or the binding of LPS results in a conformational change that allows higher affinity OspC3 binding to caspase-11. This priming role may explain why caspase-11 must be primed by type I or II IFN to enable cytosolic LPS detection, whereas caspase-4 does not strictly require IFN priming (Aachoui et al., 2013, 2015; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Hagar et al., 2013; Kayagaki et al., 2011; Rathinam et al., 2012). Further biochemical work is required to elucidate these key differences between caspase-11 and caspase-4 interaction with OspC3. Nevertheless, our study reveals that OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS detection in a broad array of mammals.

Here, we used an intraperitoneal infection route to gain insight into the in vivo importance of OspC3 inhibition of caspase-11 sensing of Shigella in primary innate immune cells, including macrophages and neutrophils. Previously, we showed that inflammasome-gasdermin D-driven pyroptosis is important in defense against B. thailandensis (Kovacs et al., 2020), yet wild-type mice are unable to clear S. flexneri despite activating pyroptosis and IL-1β through caspase-1. In contrast, we found that S. flexneri lacking OspC3 is detected by both caspase-1 and -11, resulting in enhanced clearance and survival. The activity of caspase-11 against S. flexneri appears to be independent of caspase-1, as Casp1−/− and caspase-1 proxy NLRC-ASCDKO mice are as resistant as wild-type mice. We previously found that caspase-1 is important for caspase-11 activity during defense, as it provides a priming signal upstream of caspase-1. Caspase-1-activated IL-18 induces IFN-γ to prime caspase-11 clearing 20000000 CFU of B. thailandensis in one day (Aachoui et al., 2015). Caspase-11 priming can also be achieved by the TLR4 agonist LPS through IFN-β signaling pathway (Aachoui et al., 2013, 2015; Broz et al., 2012; Case et al., 2013; Hagar et al., 2013; Rathinam et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesize that B. thailandensis LPS is a weak TLR4 agonist (Novem et al., 2009), resulting in insufficient IFN-β expression to prime caspase-11. In contrast, S. flexneri LPS is a robust TLR4 agonist that enhances IFN-β induction (Paciello et al., 2013), bypassing caspase-1 activity upstream of caspase-11 during S. flexneri infection.

We also found that caspase-11 is dominant while caspase-1 is dispensable for defense against S. flexneri lacking OspC3. We traced these differences to the role of neutrophil inflammasomes during defense against intra-cytoplasmic pathogens. We previously showed that caspase-1 activation fails to clear B. thailandensis from neutrophils, whereas caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis efficiently accomplishes this task (Kovacs et al., 2020). Therefore, we conclude that caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis is essential in defense against B. thailandensis and find this is also true during defense against S. flexneri ΔospC3. S. flexneri can target the neutrophil cytosol and activate caspase-1 to promote gasdermin D cleavage and IL-1β release but does not trigger pyroptosis. Mechanisms by which neutrophils resist caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis remain ill defined; however, a recent study found that caspase-1 activation does not result in significant accumulation of gasdermin D on the neutrophil plasma membrane (Karmakar et al., 2020). In contrast, neutrophil exposure to S. flexneri lacking OspC3 drives caspase-11-dependent pyroptosis and bacterial clearance. Historically, it was proposed that pyroptosis is beneficial for bacteria, allowing S. flexneri to escape macrophages, induce local inflammation, and infect epithelial cells from the basolateral side (Ashida et al., 2014; Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2010; Schnupf and Sansonetti, 2019). We propose the reverse model in which pyroptosis is beneficial for the host and that S. flexneri inhibits pyroptosis, depriving neutrophils from efficient clearance of the pathogen.

At the conception of this study, S. flexneri was believed to colonize human but not mouse intestinal epithelium. Since OspC3 suppresses cytosolic LPS sensing by inhibiting caspase-4, but may not inhibit murine caspase-11 activity, Kobayashi et al. proposed that OspC3 could be the key to why Shigella cannot infect mice (Kobayashi et al., 2013). However, a recent study by Mitchell et al. revealed NAIP-NLRC4 detection as the major driver that protects mice against oral Shigella infection (Mitchell et al., 2020). Starting from the assumption that S. flexneri does not suppress caspase-11 since it does not bind to OspC3 as reported by (Kobayashi et al., 2013), Mitchell et al. found that the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome, independently of caspase-11, drives exfoliation of epithelial cells to limit Shigella replication and spread in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), preventing murine gut colonization (Mitchell et al., 2020). Interestingly, Shigella also suppresses human NAIP–NLRC4, disabling both T3SS and cytosolic LPS sensing in humans (Kobayashi et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2020). Since (1) both epithelium-intrinsic NAIP-NLRC4 and caspase-11 inflammasomes drive pyroptosis and exfoliation of dying cells to clear intra-cytoplasmic gram-negative bacteria (Knodler et al., 2014; Rauch et al., 2017; Sellin et al., 2014) and (2) in light of the ability of Shigella to evade murine cytosolic LPS sensing through OspC3, we predict caspase-11 plays a similar role in mice to prevent gut colonization. In addition, our data reveal an important role for neutrophil inflammasomes in defense against Shigella. Therefore, it is possible that Shigella drives such significant pathology in humans by evading the dual surveillance of NLRC4 and caspase-4 in IECs and neutrophils.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we found that S. flexneri OspC3 binds to IFNs primed caspase-11 to suppress cytosolic sensing of LPS. In contrast, OspC3 inhibition of caspase-4 did not strictly require IFN-γ priming. The mechanism by which IFNs prime caspase-11 has not been completely defined yet and was not addressed in this study. It was proposed that S. flexneri triggers caspase-1 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis to escape macrophages and infects epithelial cells from the basolateral side to promote gut infection. Here, we demonstrate that it additionally inhibits neutrophil cytosolic sensing by caspase-11 to evade clearance and cause morbidity in a systemic model of infection. However, because S. flexneri is a gastro-intestinal pathogen that ultimately infects murine epithelial cells causing shigellosis, future studies need to address the specific role of LPS sensing in the epithelial niche to understand the importance of the caspase-11-gasdermin D axis during the Shigella-host inflammasomes interplay.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-mouse GSDMD (clone EPR19828) | Abcam | Cat# ab209845; RRID: AB_2783550 |

| Rabbit anti-DFNA5/Gsdme (clone EPR19859) | Abcam | Cat# ab215191; RRID: AB_2737000 |

| Mouse anti-mouse caspase-1 p20 (clone Casper-1) | AdipoGen | Cat# AG-20B-0042-C100; RRID: AB_2755041 |

| Rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 9661; RRID: AB_2341188 |

| Rabbit anti-mouse caspase-11 (clone EPR18628) | Abcam | Cat# ab180673 |

| Rabbit anti-Asc (clone AL177) | AdipoGen | Cat# AG-25B-0006; RRID: AB_2490440 |

| Rabbit anti-BID | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2003; RRID: AB_10694562 |

| Mouse anti-MBP | New England Biolabs | Cat# E8032; RRID: AB_1559730 |

| Mouse anit-DYKDDDDK Tag (clone 9A3) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8146; RRID: AB_10950495 |

| Mouse anti-HA.11 | BioLegend | Cat# 901513; RRID: AB_2565335 |

| Mouse anti-actin (clone ACTN05 (C4)) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# MA5-11869; RRID: AB_11004139 |

| Rabbit anti-GAPDH (clone 14C10) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 2118; PRID: AB_561053 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Wild-type S. flexneri: S. flexneri 2457T | Labrec et al., 1964 | N/A |

| S. flexneri BS103: S. flexneri 2457T (virulence plasmid cured) | Maurelli et al., 1984 | N/A |

| S. flexneri ΔospC3: S. flexneri 2457T ΔospC3 | Mou et al., 2018 | N/A |

| S. flexneri ΔospC3 + ospC3: S. flexneri 2457T ΔospC3/pOspC3: pCMD136-endP-ospC3 | Mou et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Ultrapure LPS, E. coli O111:B4 | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-3pelps |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Pam3CSK4 | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-pms |

| Recombinant mouse IFN-γ | PeproTech | Cat# 315-05 |

| Poly(dA:dT) naked | InvivoGen | Cat# tlrl-patn |

| Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11668019 |

| IPTG | Apex | Cat# 367-93-1 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Mouse IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 DuoSet ELISA | R&D Systems | Cat# DY401 |

| Neutrophil Isolation Kit, mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-097-658 |

| pMAL™ Protein Fusion and Purification System | New England Biolabs | Cat# E8200 |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human: Embryonic kidney cells: 293T | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Wild type (WT): C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX# 000664 |

| Mouse: Nlrc4-AscDKO: C57BL/6N | Aachoui et al., 2015 | N/A |

| Mouse: Casp1–/–: C57BL/6N | Rauch et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Mouse: Casp11–/–: C57BL/6N | Kayagaki et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Mouse: Casp1–/–Casp11129mut/129mut referred to as Casp1-11DKO | Kuida et al., 1995 | N/A |

| Mouse: Gsdmd–/–: C57BL/6 | Rauch et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Mouse: Casp11fl/fl: C57BL/6 | Cheng et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Mouse: Mrp8-cre: B6.Cg-Tg(S100A8-cre,-EGFP)1Ilw/J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX# 021614 |

| Mouse: 129/SvEv: 129S1/SvImJ | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX# 002448 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLenti-EF1a-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro | OriGene | Cat# PS100085 |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro-Casp-1 | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro-Casp-4 | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro-Casp-5 | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro-Casp-11 | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-HA | This paper | N/A |

| pLenti-EF1a-C-HA-OspC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Prism 5 | GraphPad | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Youssef Aachoui (YAachoui@uams.edu).

Materials availability

This study generated Casp-1, Casp-11, Casp-4, Casp-5 and ospC3 plasmids. All materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze any computational data sets/codes.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Wild type C57BL/6 (Jackson # 000664), Casp1–/– (Rauch et al., 2017), Casp11–/– (Kayagaki et al., 2011), Casp1-11DKO (Kuida et al., 1995), Nlrc4-AscDKO (Mariathasan et al., 2004), Gsdmd–/– (Rauch et al., 2017), 129/SeVe (Jackson # 002448), Mrp8-Cre (Jackson # 021614), and Casp11fl/fl (Cheng et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2018) mice were used in this study. All mice used in this study, except 129/SeVe, were in C57BL/6 genetic background and were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. For the deletion of caspase-11 in neutrophils, Casp11fl/fl mice were crossed with Mrp8-Cre. Mice which were heterozygous for the floxed gene and hemizygous for the Mrp8-cre were backcrossed to mice homozygous for the floxed gene. Both female and male mice aged between 6 and 12 weeks were randomly subjected to the experiments and there was no difference in experimental results due to sex differences. All protocols met the guidelines of the US National Institutes of Health for the humane care of animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Cell lines and primary cell cultures

HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were prepared from the femur and tibia of both male and female mice by culturing in DMEM containing the additives above and 20% L929 cell-conditioned media for 7 days. All cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Method details

In vivo infection

Wild type Shigella flexneri (Strain 2457T) and S. flexneri ΔospC3 were grown in tryptic soy agar plates containing 0.01% Congo red to select virulent plasmid-containing red colonies. For in vivo infection, a single red colony of wild type S. flexneri or ΔospC3 mutant were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) overnight at 37°C and back-diluted (1:50) in fresh TSB for 2 h until the OD600 reaches 1.0. Bacteria were centrifuged and washed three times with PBS before inoculation of mice. For monotypic wild type S. flexneri and S. flexneri ΔospC3 challenges, mice were infected with 5 × 107 CFU of bacteria via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route and 24 h post-infection, spleens and livers were collected and homogenized in sterile PBS. Viable CFU in homogenates were enumerated by plating serial dilutions on tryptic soy agar plates. For lethal challenges, mice were infected i.p. with 7.5 x 107 CFU of bacteria and monitored for 10 days. For numbers of mice used in lethal challenges, see Table S1. For studies of co-infection with wild type S. flexneri and S. flexneri ΔospC3, mice were infected with 2.5x107 CFU each of wild type S. flexneri (ampicillin resistant) and S. flexneri ΔospC3 (kanamycin resistant). Spleens and livers were harvested 24 h post-infection and homogenized in sterile PBS. Viable CFU in homogenates were enumerated by plating serial dilutions on tryptic soy agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and kanamycin (50 μg/mL), respectively. Bacterial competitive indices were calculated as the log of (S. flexneri ΔospC3/S. flexneri wild type).

Transfection

DNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Protein expression and purification

The ospC3 gene was amplified from S. flexneri wild type (strain 2457T) and cloned into pMAL-c5X vector (NEB). Expression and purification of OspC3 fused to maltose binding protein (MBP) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the pMAL Protein Fusion and Purification System (NEB #E8200) with slight modifications. Briefly, BL21 Escherichia coli (NEB Express) containing the pMAL-mock or pMAL-ospC3 plasmid were grown overnight at 37°C and then back diluted (1:00) into 500 mL of LB containing 2% glucose and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. E. coli was grown at 37°C until OD600 reached 0.6, followed by addition of IPTG (0.5 mM) to induce the expression of MBP or MBP-OspC3 proteins. Then, cells were allowed to additionally grow at 30°C overnight. Cells containing MBP fusion proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 6000 X g for 15 min at 4°C and lysed in column buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium azide, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and protease inhibitors cocktail) followed by sonication (10 bursts for 30 s each) on ice. After centrifugation at 16,000 X g for 20 min at 4°C, supernatants were collected and passed through a column containing 500 μL of amylose resin (NEB). The column was then washed with the same buffer containing 0.5 mM maltose to remove non-specific proteins that bind weakly to the column. Protein elution was performed with column buffer containing 10 mM maltose. Eluted protein was dialyzed and concentrated in PBS using centrifugal filters (Genesee). The concentration of MBP and MBP-OspC3 were estimated using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Purified proteins were aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use.

In vitro infection and detection of inflammasome activation

For in vitro infection, S. flexneri wild type, ΔospC3 mutant, and ΔospC3 + ospC3 complementation strains were grown in TSB overnight at 37°C and back-diluted (1:50) in fresh TSB for 2 hr until the OD600 reached 1.0. Bacteria were centrifuged and washed three times with PBS and finally resuspended in opti-MEM before infection. For macrophage infections, BMMs cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5x104 cells/well, followed by priming with LPS (50 ng/mL) overnight. Cells were infected (MOI 50), centrifuged at 700 X g for 10 min and then incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. After 1 hr, 100 μg/mL gentamicin was added to macrophages to eliminate extracellular bacteria and supernatants or cell lysates were collected at 4 hr post-infection. For MBP-OspC3 overexpression experiments, primed BMMs were transfected with purified MBP or MBP-OspC3 using Lipofectamine 2000 for 4 hr. After washing 3 times, cells were stimulated with LPS (5 μg/mL) or poly(dA:dT) (1 μg/mL) using Lipofectamine 2000, followed by incubation at 37°C for 4 hr. For neutrophil infection, bone marrow neutrophils were isolated using a Neutrophil Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 4x105 cells/well. Neutrophils were primed with 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (InvivoGen) for 4 hr. Cells were infected (MOI 100), centrifuged at 700 X g for 10 min and then incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. After 1 hr, 100 μg/mL gentamicin was added to neutrophils to eliminate extracellular bacteria and supernatants or cell lysates were collected at 4 hr post-infection. Additionally, for cytotoxicity assay, lysis solution was added to untreated cells to generate the maximum LDH release control. Culture medium alone was prepared to correct the background absorbance. The absorbance of supernatants at 492 nm was measured using a microplate reader (FLUOstar Omega; BMG labtech). Cytotoxicity was defined as the percentage of total LDH released into the supernatant to the maximum LDH release control (Rayamajhi et al., 2013). IL-1β secretion was determined by ELISA (R&D Systems). Lysates and supernatants were combined and analyzed by Western blot for gasdermin D (EPR19828; Abcam), caspase-1 (Casper-1; AdipoGen), caspase-11 (EPR18628; Abcam), MBP (NEB), actin (ACTN05 (C4); Invitrogen), or GAPDH (14C10; Cell signaling Technology).

Bacterial lysates preparation

To prepare extracellular bacterial lysate, S. flexneri was grown in TSB overnight at 37°C and back-diluted in fresh TSB for 2 hr until the OD600 reached 1.0. 1 mL of bacterial culture was washed 3 times with PBS. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of PBS and then boiled for 10 min, followed by centrifugation to clear bacterial lysate. For intracellular bacterial lysate, Casp1-11DKO BMDMs were infected with S. flexneri (MOI 50) for 4 hr. Extracellular bacteria were eliminated by adding gentamicin 1 hr post-infection. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and collected in lysis buffer (PBS containing 1% Triton X-100). After centrifugation, pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of PBS and then boiled for 10 min, followed by centrifugation to clear bacterial lysate. To eliminate canonical inflammasome agonists (Hagar et al., 2013), both bacterial lysates were treated with DNase (10 μg/mL) and RNase (10 μg/mL) for 3 hr at 37°C. Additionally, Proteinase K (100 μg/mL) was added to digest proteins in bacterial lysates and incubated at 37°C for 2 hr.

In vitro pulldown

Casp-1, Casp-11, Casp-4, and Casp-5 were cloned into pLenti-EF1A-C-Myc-DDK-IRES-Puro vector and ospC3 was cloned into pLenti-EF1a-C-HA-IRES-Puro vector, and used to transfect HEK293T cells in 90-mm dishes. 48 h after transfection, cells were collected and lysed at 4°C in lysis buffer (PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor), followed by clarification of lysates by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. BMDM macrophages were primed with 50 ng/mL LPS overnight and subsequently transfected with 5 μg/mL LPS or not. 3 h later, cells were harvested and lysed at 4°C in lysis buffer, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. First, anti-HA conjugated-dynabeads were incubated with lysates from OspC3-expressing cells at 4°C overnight and beads were washed 3 times with the same lysis buffer. Lysates from Caspase-expressing cells or BMM lysates were added to beads and incubated at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 50 μL of 2X sample buffer, followed by boiling for 10 min and separation by SDS-PAGE.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software. Two-tailed Student's t-test was used to determine the statistical significance between two samples originated from the same population (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ns: not significant). Statistical significance between more than two samples was determined by one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA with a statistical threshold of p ≤ 0.05. Mouse survival curves were estimated by log rank (Mantel–Cox) test using Bonferroni-corrected threshold for statistical significance of p ≤ 0.003. Error bars depict mean ± SEM. Groups that do not share a letter are significantly different.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Marcia Goldberg and Cammie Lesser for providing S. flexneri wild-type, ΔospC3, and ΔospC3 + ospC3 complementation strains. We also thank Vishva Dixit, Nobuhiko Kayagaki, and Russell Vance for sharing mice. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) P20-GM103625 and Medical Research Endowment intramural funding from the UAMS College of Medicine to Y.A. We also acknowledge the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Inflammatory Responses (CMPHIR) for continued support.

Author contributions

C.O., A.V., M.H., B.H., and Y.A. performed experiments and analyzed results. C.O., A.V., and Y.A. wrote the manuscript. Y.A. led the project.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 20, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102910.

Supplemental information

References

- Aachoui Y., Kajiwara Y., Leaf I.A., Mao D., Ting J.P.Y., Coers J., Aderem A., Buxbaum J.D., Miao E.A. Canonical inflammasomes drive IFN-γ to prime caspase-11 in defense against a cytosol-invasive bacterium. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aachoui Y., Leaf I.A., Hagar J.A., Fontana M.F., Campos C.G., Zak D.E., Tan M.H., Cotter P.A., Vance R.E., Aderem A., Miao E.A. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science. 2013;339:975. doi: 10.1126/science.1230751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abram C.L., Roberge G.L., Hu Y., Lowell C.A. Comparative analysis of the efficiency and specificity of myeloid-Cre deleting strains using ROSA-EYFP reporter mice. J. Immunol. Methods. 2014;408:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa E., Karasawa T., Watanabe S., Komada T., Kimura H., Kamata R., Ito H., Hishida E., Yamada N., Kasahara T. GSDME-dependent incomplete pyroptosis permits selective IL-1α release under caspase-1 inhibition. iScience. 2020;23:101070. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida H., Kim M., Sasakawa C. Manipulation of the host cell death pathway by Shigella. Cell. Microbiol. 2014;16:1757–1766. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P., Ruby T., Belhocine K., Bouley D.M., Kayagaki N., Dixit V.M., Monack D.M. Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature. 2012;490:288–291. doi: 10.1038/nature11419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker S.W., Brewer S.M., Massis L.M., Napier B.A., Monack D.M. A rapid caspase-11 response induced by IFNγ priming is independent of guanylate binding proteins. iScience. 2020;23:101612. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case C.L., Kohler L.J., Lima J.B., Strowig T., de Zoete M.R., Flavell R.A., Zamboni D.S., Roy C.R. Caspase-11 stimulates rapid flagellin-independent pyroptosis in response to Legionella pneumophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:1851–1856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211521110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.W., Demarco B., Broz P. Beyond inflammasomes: emerging function of gasdermins during apoptosis and NETosis. EMBO J. 2020;39:e103397. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019103397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.W., Monteleone M., Boucher D., Sollberger G., Ramnath D., Condon N.D., von Pein J.B., Broz P., Sweet M.J., Schroder K. Noncanonical inflammasome signaling elicits gasdermin D-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci. Immunol. 2018;3 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K.T., Xiong S., Ye Z., Hong Z., Di A., Tsang K.M., Gao X., An S., Mittal M., Vogel S.M. Caspase-11-mediated endothelial pyroptosis underlies endotoxemia-induced lung injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2017;127:4124–4135. doi: 10.1172/jci94495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers B., Mayer-Scholl A., Walker T., Tang C., Weinrauch Y., Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil antimicrobial proteins enhance Shigella flexneri adhesion and invasion. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:1134–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L., Amer A., Body-Malapel M., Kanneganti T.-D., Özören N., Jagirdar R., Inohara N., Vandenabeele P., Bertin J., Coyle A. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1β in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán J.E., Lara-Tejero M., Marlovits T.C., Wagner S. Bacterial type III secretion systems: specialized nanomachines for protein delivery into target cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;68:415–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar J.A., Powell D.A., Aachoui Y., Ernst R.K., Miao E.A. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase-11: implications in TLR4-independent endotoxic shock. Science. 2013;341:1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1240988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W.-t., Wan H., Hu L., Chen P., Wang X., Huang Z., Yang Z.-H., Zhong C.-Q., Han J. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin-1β secretion. Cell Res. 2015;25:1285–1298. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig R., Dilucca M., Boucher D., Chen K.W., Hancz D., Demarco B., Shkarina K., Broz P. Caspase-1 cleaves Bid to release mitochondrial SMAC and drive secondary necrosis in the absence of GSDMD. Life Sci. Alliance. 2020;3:e202000735. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermansson A.K., Paciello I., Bernardini M.L. The orchestra and its maestro: Shigella's fine-tuning of the inflammasome platforms. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016;397:91–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41171-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Qi L., Li L., Li Y. The caspase-3/GSDME signal pathway as a switch between apoptosis and pyroptosis in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2020;6:112. doi: 10.1038/s41420-020-00349-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen I., Zhang Y., Krantz B.A., Miao E.A. Pyroptosis triggers pore-induced intracellular traps (PITs) that capture bacteria and lead to their clearance by efferocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:2113. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiwara Y., Schiff T., Voloudakis G., Gama Sosa M.A., Elder G., Bozdagi O., Buxbaum J.D. A critical role for human caspase-4 in endotoxin sensitivity. J. Immunol. 2014;193:335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar M., Minns M., Greenberg E.N., Diaz-Aponte J., Pestonjamasp K., Johnson J.L., Rathkey J.K., Abbott D.W., Wang K., Shao F. N-GSDMD trafficking to neutrophil organelles facilitates IL-1β release independently of plasma membrane pores and pyroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2212. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N., Stowe I.B., Lee B.L., O’Rourke K., Anderson K., Warming S., Cuellar T., Haley B., Roose-Girma M., Phung Q.T. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015;526:666. doi: 10.1038/nature15541. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature15541#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N., Warming S., Lamkanfi M., Vande Walle L., Louie S., Dong J., Newton K., Qu Y., Liu J., Heldens S. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N., Wong M.T., Stowe I.B., Ramani S.R., Gonzalez L.C., Akashi-Takamura S., Miyake K., Zhang J., Lee W.P., Muszyński A. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science. 2013;341:1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1240248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodler L.A., Crowley S.M., Sham H.P., Yang H., Wrande M., Ma C., Ernst R.K., Steele-Mortimer O., Celli J., Vallance A. Noncanonical inflammasome activation of caspase-4/caspase-11 mediates epithelial defenses against enteric bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Ogawa M., Sanada T., Mimuro H., Kim M., Ashida H., Akakura R., Yoshida M., Kawalec M., Reichhart J.M. The Shigella OspC3 effector inhibits caspase-4, antagonizes inflammatory cell death, and promotes epithelial infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs S.B., Oh C., Maltez V.I., McGlaughon B.D., Verma A., Miao E.A., Aachoui Y. Neutrophil caspase-11 is essential to defend against a cytosol-invasive bacterium. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107967. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K., Lippke J.A., Ku G., Harding M.W., Livingston D.J., Su M.S., Flavell R.A. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutsch M., Sistemich L., Lesser C.F., Goldberg M.B., Herrmann C., Coers J. Direct binding of polymeric GBP1 to LPS disrupts bacterial cell envelope functions. EMBO J. 2020;39:e104926. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020104926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrec E.H., Schneider H., Magnani T.J., Formal S.B. Epithelial cell penetration as an essential step in the Pathogenesis of bacillary dysentery. J. Bacteriol. 1964;88:1503–1518. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.5.1503-1518.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M., Dixit V.M. Manipulation of host cell death pathways during microbial infections. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.L., Stowe I.B., Gupta A., Kornfeld O.S., Roose-Girma M., Anderson K., Warming S., Zhang J., Lee W.P., Kayagaki N. Caspase-11 auto-proteolysis is crucial for noncanonical inflammasome activation. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:2279–2288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Jiang W., Yu Q., Liu W., Zhou P., Li J., Xu J., Xu B., Wang F., Shao F. Ubiquitination and degradation of GBPs by a Shigella effector to suppress host defence. Nature. 2017;551:378. doi: 10.1038/nature24467. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature24467#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S., Newton K., Monack D.M., Vucic D., French D.M., Lee W.P., Roose-Girma M., Erickson S., Dixit V.M. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurelli A.T., Blackmon B., Curtiss R., 3rd Loss of pigmentation in Shigella flexneri 2a is correlated with loss of virulence and virulence-associated plasmid. Infect. Immun. 1984;43:397–401. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.397-401.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao E.A., Alpuche-Aranda C.M., Dors M., Clark A.E., Bader M.W., Miller S.I., Aderem A. Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1β via Ipaf. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:569–575. doi: 10.1038/ni1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao E.A., Leaf I.A., Treuting P.M., Mao D.P., Dors M., Sarkar A., Warren S.E., Wewers M.D., Aderem A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:1136. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. https://www.nature.com/articles/ni.1960#supplementary-information [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P.S., Roncaioli J.L., Turcotte E.A., Goers L., Chavez R.A., Lee A.Y., Lesser C.F., Rauch I., Vance R.E. NAIP-NLRC4-deficient mice are susceptible to shigellosis. eLife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.59022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky A.B., Byrne B.G., Whitfield N.N., Madigan C.A., Fuse E.T., Tateda K., Swanson M.S. Cytosolic recognition of flagellin by mouse macrophages restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:1093–1104. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou X., Souter S., Du J., Reeves A.Z., Lesser C.F. Synthetic bottom-up approach reveals the complex interplay of Shigella effectors in regulation of epithelial cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2018;115:6452–6457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801310115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novem V., Shui G., Wang D., Bendt A.K., Sim S.H., Liu Y., Thong T.W., Sivalingam S.P., Ooi E.E., Wenk M.R., Tan G. Structural and biological diversity of lipopolysaccharides from Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis. Clin. Vaccin. Immunol. 2009;16:1420–1428. doi: 10.1128/cvi.00472-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh C., Verma A., Aachoui Y. Caspase-11 non-canonical inflammasomes in the lung. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1895. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciello I., Silipo A., Lembo-Fazio L., Curcurù L., Zumsteg A., Noël G., Ciancarella V., Sturiale L., Molinaro A., Bernardini M.L. Intracellular Shigella remodels its LPS to dampen the innate immune recognition and evade inflammasome activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:E4345–E4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303641110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M.L.G., Poreba M., Snipas S.J., Groborz K., Drag M., Salvesen G.S. Extensive peptide and natural protein substrate screens reveal that mouse caspase-11 has much narrower substrate specificity than caspase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:7058–7067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randow F., MacMicking J.D., James L.C. Cellular self-defense: how cell-autonomous immunity protects against pathogens. Science. 2013;340:701–706. doi: 10.1126/science.1233028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam V.A., Vanaja S.K., Waggoner L., Sokolovska A., Becker C., Stuart L.M., Leong J.M., Fitzgerald K.A. TRIF licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 2012;150:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch I., Deets K.A., Ji D.X., von Moltke J., Tenthorey J.L., Lee A.Y., Philip N.H., Ayres J.S., Brodsky I.E., Gronert K., Vance R.E. NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasomes Coordinate intestinal epithelial cell expulsion with eicosanoid and IL-18 release via activation of caspase-1 and -8. Immunity. 2017;46:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K., Marteyn B., Sansonetti P.J., Tang C.M. Life on the inside: the intracellular lifestyle of cytosolic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayamajhi M., Zhang Y., Miao E.A. Detection of pyroptosis by measuring released lactate dehydrogenase activity. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1040:85–90. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-523-1_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T., Zamboni D.S., Roy C.R., Dietrich W.F., Vance R.E. Flagellin-deficient Legionella mutants evade caspase-1- and naip5-mediated macrophage immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo A.J., Vasudevan S.O., Méndez-Huergo S.P., Kumari P., Menoret A., Duduskar S., Wang C., Pérez Sáez J.M., Fettis M.M., Li C. Intracellular immune sensing promotes inflammation via gasdermin D-driven release of a lectin alarmin. Nat. Immunol. 2021;22:154–165. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00844-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J.C., Boucher D., Schneider L.K., Demarco B., Dilucca M., Shkarina K., Heilig R., Chen K.W., Lim R.Y.H., Broz P. Human GBP1 binds LPS to initiate assembly of a caspase-4 activating platform on cytosolic bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3276. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16889-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnupf P., Sansonetti P.J. Shigella Pathogenesis: new insights through advanced methodologies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019;7 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAI-0023-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin M.E., Müller A.A., Felmy B., Dolowschiak T., Diard M., Tardivel A., Maslowski K.M., Hardt W.D. Epithelium-intrinsic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome drives infected enterocyte expulsion to restrict Salmonella replication in the intestinal mucosa. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhao Y., Wang K., Shi X., Wang Y., Huang H., Zhuang Y., Cai T., Wang F., Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660. doi: 10.1038/nature15514. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature15514#supplementary-information [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Gao W., Ding J., Li P., Hu L., Shao F. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature. 2014;514:187. doi: 10.1038/nature13683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Franchi L., Toma C., Ashida H., Ogawa M., Yoshikawa Y., Mimuro H., Inohara N., Sasakawa C., Nunez G. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K.V., Deng M., Ting J.P.Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya K., Nakajima S., Hosojima S., Thi Nguyen D., Hattori T., Manh Le T., Hori O., Mahib M.R., Yamaguchi Y., Miura M. Caspase-1 initiates apoptosis in the absence of gasdermin D. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2091. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandel M.P., Kim B.H., Park E.S., Boyle K.B., Nayak K., Lagrange B., Herod A., Henry T., Zilbauer M., Rohde J. Guanylate-binding proteins convert cytosolic bacteria into caspase-4 signaling platforms. Nat. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0697-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yin B., Li D., Wang G., Han X., Sun X. GSDME mediates caspase-3-dependent pyroptosis in gastric cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;495:1418–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze any computational data sets/codes.