Abstract

Background

Despite advances in pain management, postoperative pain continues to be an important problem with significant burden. Many current therapies have dose-limiting adverse effects and are limited by their short duration of action. This review examines the evidence for the efficacy and safety of cryoanalgesia in postoperative pain.

Materials and methods

This review was registered in PROSPERO and prepared in accordance with PRISMA. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were searched until July 2020. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adults evaluating perioperatively administered cryoanalgesia for postoperative pain relief.

Results

Twenty-four RCTS were included. Twenty studies examined cryoanalgesia for thoracotomy, two for herniorrhaphy, one for nephrectomy and one for tonsillectomy. Meta-analysis was performed for thoracic studies. We found that cryoanalgesia with opioids was more efficacious than opioid analgesia alone for acute pain (mean difference [MD] 2.32 units, 95 % confidence interval [CI] −3.35 to −1.30) and persistent pain (MD 0.81 units, 95 % CI –1.10 to −0.53) after thoracotomy. Cryoanalgesia with opioids also resulted in less postoperative nausea compared to opioid analgesia alone (relative risk [RR] 0.23, 95 % CI 0.06 to 0.95), but there was no difference in atelectasis (RR 0.38, 95 % CI 0.07 to 2.17).

Conclusion

Heterogeneity in comparators and outcomes were important limitations. In general, reporting of adverse events was incomplete and inconsistent. Many studies were over two decades old, and most were limited in how they described their methodology. Considering the potential, larger RCTs should be performed to better understand the role of cryoanalgesia in postoperative pain management.

Keywords: Cryoanalgesia, Pain, Postoperative pain, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

Cryoanalgesia may be associated with better pain relief and opioid reduction than intercostal nerve blocks.

-

•

Despite its potential for prolonged pain relief, its benefit in other surgical populations has not been evaluated.

-

•

Future studies should consider a larger sample size with better design.

1. Introduction

Pain is one of the most common and feared complications of surgery [1]. Postoperative pain is both common and an important health problem affecting more than 80 % of post-surgical patients, with up to 75 % describing their pain as moderate-to-severe [1,2]. Uncontrolled postoperative pain can have detrimental effects on patients’ physical functioning, and recovery, and can result in morbidity such as pulmonary infections, atelectasis, myocardial ischemia, and cardiac failure [3,4]. Despite increased awareness and advances in pain management strategies, poorly controlled postoperative pain continues to be an unresolved issue.

Available treatments for postoperative pain relief are limited by varying efficacy and dose-limiting adverse effects, leaving a significant unmet need for patients [5]. Opioids continue to be the mainstay of postoperative pain management despite their well-known side effects and risks of abuse, misuse, and addiction [5]. Known regional anesthetic techniques have been shown to be an effective part of multimodal analgesia for many surgical procedures but are unfortunately limited by their short duration of action [6]. Additionally, continuous peripheral nerve blocks are limited by their infection risk, catheter dislocation, and pump malfunction [7].

A promising alternative postoperative pain treatment option is cryoanalgesia. Treatment with cryoanalgesia involves cooling specific nerves to reversibly inhibit peripheral nerve function, with subsequent pain relief potentially lasting weeks to months [8]. This typically involves the use of a needle or cryoprobe at very low temperatures for contact cooling of a selected peripheral nerve (Fig. 1) [9]. Application temperatures vary but must achieve at least −20°C and must not exceed −100°C to be effective and safe [10]. If a nerve is successfully cooled to a temperature in this range, the duration of analgesia is dependent primarily on the length of the lesion [10]. As with temperature, there is variation in the literature with regard to the preferred number and timing of freeze-thaw cycles. Relative contraindications to cryoanalgesia include diabetes mellitus, cold urticaria, cryoglobulinemia, and Raynaud's disease [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]].

Fig. 1.

Cryoprobe cooling a selected peripheral nerve.

Cryoanalgesia has been frequently used to treat a variety of chronic pain conditions using ultrasound-guided cryoprobe insertion [14]. However, as an opioid-sparing therapy with a prolonged duration of action, cryoanalgesia may offer another potential option for postoperative pain management [15]. Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess current evidence of efficacy and safety of cryoanalgesia for the management of postoperative pain.

2. Methods

We established a protocol prior to the review process that included the review question, search strategy, study selection and analysis. The review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (registration number CRD42020195702) and prepared in accordance with recommendations specified in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16] and AMSTAR (Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews) Guidelines. The completed PRISMA and AMSTAR checklist is provided in Appendix A.

2.1. Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases from their inception until July 2020. The search strategy included terms related to cryoanalgesia, postoperative pain, and surgery, and excluded studies that were not published in English, as we did not have the capability to translate studies from all non-English publications. As an example, the search strategy for MEDLINE is shown in Appendix B. Bibliographies of relevant reviews and selected studies were also examined to identify additional published or unpublished data.

2.2. Study selection

Two reviewers (R.P. and M.C.) independently and in duplicate evaluated studies for eligibility. Screening was performed on titles and abstracts using Covidence software (www.covidence.org). We excluded studies that clearly did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, and full-text screening was performed on citations thought to be potentially eligible. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. If necessary, a third reviewer (H.S.) was consulted.

2.2.1. Studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the use of cryoanalgesia for postoperative pain. RCTs form level 1 evidence and with an intervention such as cryoanalgesia, there is a higher potential for performance and observer bias, so we did not consider including observational studies. Studies investigating any type of surgical procedure were eligible for inclusion in this review.

2.2.2. Participants

We included studies with adults (aged 18 years and over) undergoing any type of surgery.

2.2.3. Interventions

We included studies that administered cryoanalgesia during the perioperative period for the management of postoperative pain. We excluded interventions labelled as ‘cryoanalgesia’ that did not use a cryoprobe.

2.3. Data extraction

Data from selected studies were extracted in duplicate in using standardized extraction forms after checking for consistency between two reviewers (R.P. and M.C.). The forms captured information regarding the type of surgeries the participants underwent, details of cryoanalgesia therapy, participant characteristics, risk of bias domains as per Cochrane risk of bias instrument, and our primary and secondary outcome measures.

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was postoperative pain relief in terms of either 1) pain intensity, or 2) the use of postoperative opioids and rescue analgesics. Pain intensity and use of postoperative opioids and rescue analgesics were extracted for all time points.

2.4.2. Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included duration of cryoanalgesia blockade and participants experiencing any adverse event (e.g., opioid-related side effects, postoperative nausea and vomiting, nerve injury, etc.). We also extracted information on whether pain was measured at rest, with movement, or if it was not specified.

2.5. Data analyses

Extracted data were compiled in Microsoft Excel for analysis. Data were pooled if there were two or more studies contributing to an outcome domain. For pooling, we considered the most common duration of follow-up period for acute pain (7 days or less) and persistent pain (1 month and longer). Continuous scores used to express pain relief were converted to 0–10 numerical rating scores, as it is commonly used and easy to interpret [17]. Analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program], Version 5.3, Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. If we did not observe much study variance based on study population, interventions, and comparators, a fixed effects model was considered for pooling. Otherwise, we utilized a random effects model for pooling. We calculated the risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) or standardized MD for continuous outcomes, as appropriate, along with the associated 95 % confidence intervals (CI). To capture outcomes for which there was a paucity of data or it was inappropriate to combine studies, a narrative synthesis approach in the form of a table was utilized. The findings were organized based on surgical procedure and intervention/comparator(s). We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic.

2.6. Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias for included RCTs was assessed using criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions [18]. We assessed the following for each study: 1) random sequence generation for possible selection bias; 2) allocation concealment for possible selection bias; 3) blinding of participants and personnel for possible performance bias; 4) blinding of outcome assessment for possible detection bias; 5) incomplete outcome data for possible attrition bias; and 6) selective reporting for possible reporting bias.

3. Results

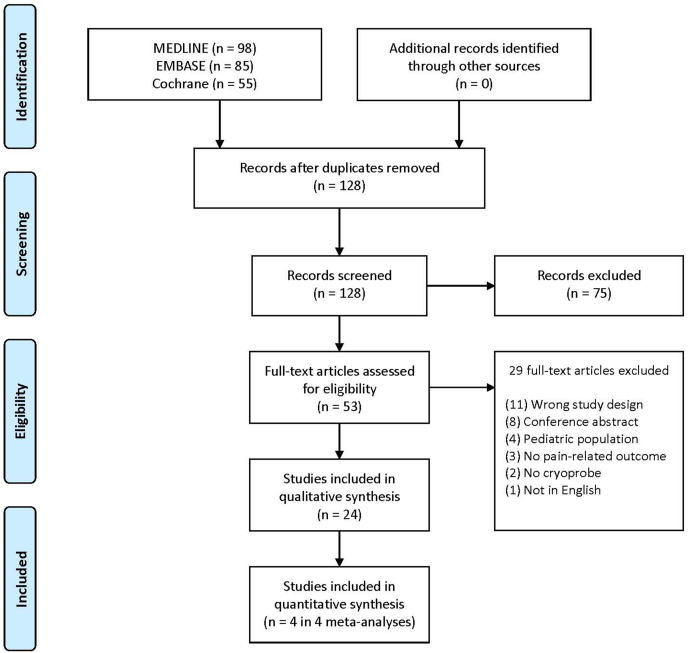

Our search yielded 128 citations and after removal of duplications 53 studies were considered for full-text review. After reading the full articles for these 53 studies, we excluded 29 studies (Appendix C). No additional studies were identified in reference lists of included studies. We show our selection process in Fig. 2. Twenty-four RCTs fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in qualitative synthesis. Four studies were included in quantitative synthesis as they were compatible across interventions, comparators, and outcome measures.

Fig. 2.

Study flow diagram.

3.1. Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies, including the study population, intervention, and comparator, are reported in Table 1. Of the 24 trials, 20 were for thoracic surgeries, two for herniorrhaphy [19,20], one for nephrectomy [21] and one for tonsillectomy [22]. Interventions included cryoanalgesia alone [23], cryoanalgesia with opioid analgesia [[19], [20], [21], [22],[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]], or cryoanalgesia with epidural and opioid analgesia [41,42]. These combinations are described for each study in Table 1. Cryoanalgesia was administered intraoperatively in all studies. Comparators included epidural analgesia [[33], [34], [35], [36],[40], [41], [42]], intercostal nerve blocks [[37], [38], [39]], opioid analgesia only [[19], [20], [21], [22],[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]], nonopioid analgesia only [23], and non-divided intercostal muscle flap [24]. Only one study reported using a sham cryoanalgesia treatment in the comparator arm [19]. Fourteen studies did not report whether pain scores were at rest or with movement [[22], [23], [24], [25],27,[29], [30], [31],[33], [34], [35],37,39,40]. Narcotic use was reported predominantly in terms of analgesic consumption and frequency of use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author, Year | Population | Procedure | Cryoanalgesia Application Location | Intervention Concurrent Analgesia | Comparator | Trial Size (Cryoanalgesia, Comparator) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brichon [33], 1994 | Parenchymal disease | Thoracotomy | 5 IC nerves | OA, NOA | TE, OA, NOA | 41, 33 |

| Ju [36], 2008 | Lung or esophageal disease | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | OA | TE, OA | 53, 54 |

| Yang [41], 2004 | Malignant disease | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | TE, OA, NOA | TE, OA, NOA | 45, 45 |

| Mustola [42], 2011 | Infection or tumor | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | TE, OA, NOA | TE, OA, NOA | 21, 21 |

| Momenzadeh [25], 2011 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | OA | OA | 30, 30 |

| Ma [29], 2009 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 4 IC nerves | OA | OA | 60, 60 |

| Katz [37], 1980 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | Cryoanalgesia used at 5–6 IC nerves | OA | INB, OA | 15, 9 |

| Keenan [32], 1983 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 6 IC nerves | OA (Group 2) | OA (Group 4) | 15, 15 |

| Muller [30], 1989 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 4 IC nerves | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 30, 33 |

| Miguel [35], 1993 | Malignant disease | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | OA (Group 1) | OA (Group 4) LE (Group 1) |

14, 11 |

| Moorjani [27], 2001 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 4 IC nerves | OA | OA | 100, 100 |

| Joucken [38], 1987 | Lung cancer | Thoracotomy | IC nerves | OA | INB, OA (Group 2) | 15, 15 |

| Ba [23], 2014 | Lung cancer | Thoracotomy | 4 IC nerves | None | NOA | 87, 91 |

| Pastor [31], 1996 | Varied | Thoracotomy | 6 IC nerves | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 55, 45 |

| Roberts [39], 1988 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 8 IC nerves | OA | INB, OA | 71, 73 |

| Roxburgh [34], 1987 | Unspecified | Thoracotomy | 5-6 IC nerves | LE, OA, NOA | LE, OA, NOA | 23, 30 |

| Gwak [26], 2004 | Lung cancer | Thoracotomy | 3 IC nerves | OA | OA | 25, 25 |

| Sepsas [28], 2013 | Lung cancer | Thoracotomy | 4 IC nerves | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 25, 25 |

| Lu [24], 2013 | Esophageal disease | Esophagectomy or thoracotomy | 6 IC nerves | OA, NOA | NDIMF, OA, NOA | 94, 92 |

| Callesen [19], 1998 | 48 male patients with inguinal hernia | Herniorrhaphy | Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 24, 24 |

| Khiroya [20], 1986 | Inguinal hernia | Herniorrhaphy | Ilioinguinal nerve | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 36 total |

| Ahmadnia [21], 2010 | Kidney donors | Nephrectomy | 11th IC nerve | OA | OA | 15, 15 |

| Robinson [22], 2000 | Adults and children with recurrent tonsilitis | Tonsillectomy | Tonsillar fossa after tonsillectomy | OA, NOA | OA, NOA | 29, 28 |

| Graves [40], 2019 | Adults and children with pectus exacavatum | Nuss Procedure | 5 IC nerves | OA, NOA | TE, OA, NOA | 10, 10 |

IC: Intercostal; OA: Opioid analgesia; NOA: Non-opioid analgesia; TE: Thoracic epidural; INB: Intercostal nerve block; LE: Lumbar Epidural; NDIMF: Non-divided intercostal muscle flap.

3.2. Risk of bias within studies

The results of each individual risk of bias domain are presented as a risk of bias graph in Fig. 3a, and a risk of bias summary in Fig. 3b. Overall, many studies reported insufficient information to confidently assess risk of bias across multiple domains, which may be a consequence of the relatively older publication dates of many included studies. Eighteen of the 24 studies were published during or before 2010, when CONSORT guidelines were RCTs were first published. Thus, most studies were judged to be at an unclear risk of bias for most domains. Of note, with the exception of one study [19], no study reported whether they used a sham treatment in the comparator arm, or if the personnel administering the cryoprobe and participants were blinded. Therefore, all of these studies were judged to be at a high risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel.

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias. (a) Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgement about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies; (b) Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgement about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.3. Primary outcome – qualitative synthesis

The main results of pain outcomes from included studies are summarized in Table 2. Thirteen [22,23,25,[27], [28], [29],31,32,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41]] of the 24 included studies predominantly favored cryoanalgesia with regard to our primary outcome of postoperative pain relief in terms of postoperative pain intensity and opioid use. Among studies with mixed adults and children, Robinson and Purdie (2000) [22] found that acute pain scores were significantly lower in the cryoanalgesia group compared with the opioid analgesia group for participants who underwent tonsillectomy. Graves et al. [40] showed no difference in acute and chronic pain scores between thoracic epidural and cryoanalgesia when used during the Nuss procedure, but showed a significant reduction in oral opioid requirements among the cryoanalgesia group. Both herniorrhaphy studies [19,20] and one nephrectomy study [21] showed no significant difference in the primary outcomes of this review. Results of cryoanalgesia when compared to different combinations of comparators are summarized below.

Table 2.

Main results of pain outcomes from included trials of cryoanalgesia for postoperative pain.

| Author, year | Procedure | Comparator | Pain outcome measures | Pain measured at rest, with movement, or not specified? | Follow-up time | Pain outcomes (s) |

| Brichon [33], 1994 | Thoracotomy | TE, OA, NOA (Group B) | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–12 | Patients in the epidural group had better pain relief than the cryoanalgesia group on POD 1 and 2. |

| Ju [36], 2008 | Thoracotomy | TE, OA | NRS, chronic pain incidence | Rest and movement | Days 1–3, Months 1, 3, 6, 12 | No significant difference for acute pain. Fewer patients in the epidural group reported moderate or severe chronic pain on POM 6. |

| Yang [41], 2004 | Thoracotomy | TE, OA, NOA | VAS, NRS, chronic pain incidence | Rest and movement | Days 1–7, Months 1, 3, 6 | Patients who received cryoanalgesia with epidural had less pain on movement than epidural alone on POD 7. Incidence and severity of post-thoracotomy chronic pain at POM3 was worse at rest in the cryoanalgesia and epidural group than in the epidural alone group. |

| Frequency of morphine consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | Patients who received cryoanalgesia with epidural used less analgesic than epidural alone on POD 7. | |||

| Mustola [42], 2011 | Thoracotomy | TE, OA, NOA | VAS, VPS | Rest and movement | Days 1–7, Months 1, 2, 6 | Patients who received cryoanalgesia with epidural had more pain at rest than epidural alone at 12 h, POD 2, and POM 2. |

| Frequency of epidural bolus; Oxycodone requirements | N/A | Days 1–3 | No significant difference | |||

| Momenzadeh [25], 2011 | Thoracotomy | OA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–7 | Patients who received cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain than the control group on POD 1–7. |

| Pethidine consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | Mean pethidine consumption was significantly higher in the control group than the cryoanalgesia group on POD 1. Patients in the control group used pethidine until POD 7, whereas patients in the cryoanalgesia group stopped on POD 4. | |||

| Ma [29], 2009 | Thoracotomy | OA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1, 3, 5, 9, Months 1–3, 6 | Compared with the control group, pain scores in the cryoanalgesia group were significantly lower at days 1, 3, 5, 9, and 30. |

| Pethidine consumption | N/A | Days 1, 3, 5, 9 | Patients in the cryoanalgesia use used significantly less pethidine at all time points. | |||

| Katz [37], 1980 | Thoracotomy | INB, OA | NRS | Not specified | Days 1, 3, 5 | At all points in follow up, the cryoanalgesia group had significantly less pain than the comparator group. |

| Morphine consumption | N/A | Day 1 | Compared with cryoanalgesia, comparator patients required significantly more morphine on POD 1 | |||

| Keenan [32], 1983 | Thoracotomy | OA (Group 4) | VAS | Rest and movement | Days 1, 2 | Cryoanalgesia reduced pain significantly, compared with comparator at rest and on movement. Combining cryoanalgesia with indomethacin appeared to have an additive effect. |

| Papaveretum consumption | N/A | Day 1 | The combination of indomethacin and cryoanalgesia significantly reduced the need for opioid analgesia compared with comparator. | |||

| Muller [30], 1989 | Thoracotomy | OA,/NOA | Non-standard pain scale (0–4) | Not specified | Days 1–3, 5, 7 | No significant difference. |

| Methadone consumption | N/A | Days 1–3, 5, 7 | No significant difference. | |||

| Miguel [35], 1993 | Thoracotomy | OA (Group 4) | VAS, chronic pain incidence | Not specified | Days 1, 2, 5, Month 12 | Patients receiving epidural morphine had significantly lower pain scores than patients receiving cryoanalgesia on POD 0. Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less incidence of post-thoracotomy pain syndrome at POM 3. |

| Morphine consumption | N/A | Days 1, 2, 5 | No significant difference. | |||

| Moorjani [27], 2001 | Thoracotomy | OA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–7, 10, 20, Month 1 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain on POD 1–7. |

| Pethidine consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia used significantly less pethidine on POD 1–6 than patients receiving conventional analgesia. | |||

| Joucken [38], 1987 | Thoracotomy | INB, OA (Group 2) | Frequency of piritramide consumption | N/A | Hours 1-36 | Patients in the cryoanalgesia group used significantly fewer narcotic injections compared to control and intercostal block groups. |

| Ba [23], 2014 | Thoracotomy | NOA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–3, 7 Months 1, 6 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain than patients receiving parecoxib on POD 1–3, 7 and POM 1. |

| Pastor [31], 1996 | Thoracotomy | OA, NOA | Non-standard pain scale (0–5) | Not specified | Days 1–7 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain on POD 1–7. |

| Frequency of aminopyrine consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia used significantly less major analgesia on POD 1–7 than comparator. | |||

| Roberts [39], 1988 | Thoracotomy | INB, OA | VAS (0–12) | Not specified | Days 1–3 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain on POD 1–3 than patients receiving bupivacaine block. |

| Pethidine consumption | N/A | Days 1–3 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia used significantly less pethidine on POD 1–3 than patients receiving bupivacaine block. | |||

| Roxburgh [34], 1987 | Thoracotomy | LE, OA, NOA | VPS | Not specified | Days 1–14 | No significant difference. |

| OA/NOA consumption | N/A | Days 1–14 | No significant difference. | |||

| Gwak [26], 2004 | Thoracotomy | OA | VAS, chronic pain incidence | Rest and movement | Days 1–7 | No significant difference. |

| Fentanyl consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | No significant difference. | |||

| Sepsas [28], 2013 | Thoracotomy | OA, NOA | VPS | Rest and coughing | Days 1–7, Week 2, Months 1, 2 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain at rest at all timepoints, compared to comparator. . . |

| Morphine consumption; OA/NOA frequency of consumption | N/A | Days 1–7, Week 2, Months 1, 2 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia used significantly less morphine at all timepoints, compared to comparator (Data reported in 6-h intervals). | |||

| Lu [24], 2013 | Esophagectomy with thoracotomy | NDMIF, OA, NOA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–7, Months 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly more pain at POM 6, 9, 12 than patients receiving NDIMF. . |

| Incidence of OA/NOA consumption | N/A | Days 1–7, Months 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 | Patients receiving cryoanalgesia used significantly more likely to be using oral pain medication at POM 6, 9, 12 than patients receiving NDIMF. . |

|||

| Callesen [19], 1998 | Herniorrhaphy | OA, NOA | Non-standard pain scale (0–3) | Rest and movement | Days 1–7, Months 1, 2 | No significant difference. |

| Acetaminophen consumption | N/A | Days 1–7 | No significant difference. | |||

| Khiroya [20], 1986 | Herniorrhaphy | OA, NOA | VAS | Rest | Days 1, 2, Month 3 | No significant difference. |

| Pethidine consumption; Distalgesic consumption | N/A | – | No significant difference. | |||

| Ahmadnia [21], 2010 | Nephrectomy | OA | Morphine consumption | N/A | Days 1, 2 | No significant difference. |

| Robinson [22], 2000 | Tonsillectomy | OA, NOA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1–10 | Over the duration of follow up, patients receiving cryoanalgesia had significantly less pain than comparator group. . |

| OA/NOA consumption | N/A | Month 1 | No significant difference. | |||

| Graves [40], 2019 | Nuss Procedure | TE, OA, NOA | VAS | Not specified | Days 1, 3, 5, Week 2, Months 1, 3, 12 | No significant difference. |

| OA consumption (oral morphine equivalents) | N/A | Days 1–3 | Patients who received cryoanalgesia used significantly less opioids throughout the postoperative stay than patients receiving epidural. | |||

VAS: Visual analog scale; NRS: Numeric rating scale; VPS: Verbal pain scale; NDIMF: Non-divided intercostal muscle flap; POD: Post-operative day; POM: Post-operative month; IC: Intercostal; OA: Opioid analgesia; NOA: Non-Opioid analgesia; TE: Thoracic epidural; INB: Intercostal nerve block; LE: Lumbar Epidural; NDIMF: Non-divided intercostal muscle flap.

3.3.1. Cryoanalgesia versus intercostal nerve block

All three thoracotomy studies comparing cryoanalgesia to the intercostal nerve block showed a significant reduction in opioid use among the cryoanalgesia group when compared to intercostal nerve block [[37], [38], [39]].

3.3.2. Cryoanalgesia (with or without opioid analgesia) versus opioid analgesia

Six of eight thoracotomy studies comparing cryoanalgesia (with or without opioid analgesia) to opioid analgesia favored the cryoanalgesia group in terms of postoperative pain intensity, opioid use, or both [25,[27], [28], [29],31,32]. These six studies [25,[27], [28], [29],31,32] each demonstrated lower acute pain scores in patients receiving cryoanalgesia compared to those receiving opioid analgesia. Three of these studies [[27], [28], [29]] also demonstrated lower in chronic pain scores in the cryoanalgesia group. Five studies [25,[27], [28], [29],31] all showed reduced opioid consumption among the cryoanalgesia group. The remaining two thoracotomy studies [26,30], which compared cryoanalgesia to opioid, found no significant difference between treatments with respect to the primary outcomes.

3.3.3. Cryoanalgesia versus epidural

Four thoracotomy studies that evaluated the efficacy of cryoanalgesia of intercostal nerves versus epidural for postoperative pain relief seemed to generally favor epidural [[33], [34], [35], [36]]. Two studies [33,35] showed significantly lower acute pain scores in the epidural group compared to cryoanalgesia group, and another [36] found that fewer participants reported chronic pain in the epidural group compared to the cryoanalgesia group. The last study [34] showed no significant difference in primary outcomes between patients receiving cryoanalgesia compared with epidural for thoracotomy.

3.3.4. Cryoanalgesia plus epidural versus epidural alone

Two thoracotomy studies that evaluated the efficacy of cryoanalgesia combined with epidural versus epidural alone showed mixed results [41,42]. Mustola 2011 [42] found significantly lower acute pain scores for epidural alone compared to combination therapy, and found no difference in opioid requirements between groups. Yang 2004 [41] found significantly lower acute pain scores and opioid use in combination therapy compared to epidural alone; however, incidence and severity of post-thoracotomy chronic pain was higher in the combination therapy group.

3.3.5. Cryoanalgesia versus non-opioid analgesia alone

Ba 2014 [23] was the only study that compared cryoanalgesia to non-opioid pain medication (intravenous parecoxib) for thoracotomy and found acute and chronic pain scores were significantly lower among the cryoanalgesia group.

3.3.6. Cryoanalgesia versus non-divided intercostal muscle flap

Lu 2013 [24] found that the non-divided intercostal muscle flap resulted in significant reductions in chronic pain intensity and incidence of oral pain medication consumption at months 6, 9, and 12 when compared to cryoanalgesia.

3.4. Primary outcome – quantitative synthesis

Though many included studies assessed our outcomes of interest, most comparisons could not be included for pooling due to the inconsistency within the combinations of analgesic modalities used in intervention and comparator groups. Where multiple timepoints were available, the closest timepoint to postoperative day 1 and month 1 were selected for acute and persistent pain scores, respectively, as these were the most common acute and persistent timepoints that were evaluated within our studies. Two pools of two studies each were deemed appropriate for meta-analysis.

3.4.1. Acute pain

Two studies were pooled with respect to acute pain [28,29]. Pain scores were converted into a common 0–10 NRS scale. Both studies included opioid analgesia with (n = 85) or without cryoanalgesia (n = 85) and were combined using a random effects model. Compared with no cryoanalgesia, cryoanalgesia showed significant improvement in acute pain (MD 2.32 units, 95 % CI –3.35 to −1.30, I2 = 77 %) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Acute (a) and persistent (b) postoperative pain relief as mean differences with cryoanalgesia compared with opioid analgesia.

CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

3.4.2. Persistent pain

The same two studies allowed pooling to assess the effect of cryoanalgesia on persisting pain [28,29]. Compared with no cryoanalgesia, the cryoanalgesia group showed significant improvements in persistent pain intensity (MD 0.81 units, 95 % CI –1.10 to −0.53, I2 = 17 %) (Fig. 4b).

3.5. Secondary outcomes

3.5.1. Adverse events

In general, the adverse events reporting was inconsistent and inadequate based on the available knowledge on the pain relief modalities used. All adverse events reported in more than one comparable study are summarized in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2. Nausea was more commonly reported in non-cryoanalgesia groups that received only opioid analgesia compared to groups that also received cryoanalgesia (RR 0.23, 95 % CI 0.06 to 0.95, I2 = 66 %) (Supplemental Figure 1). Atelectasis was also reported in multiple studies comparing cryoanalgesia to opioid analgesia; however, there was no difference in atelectasis between these groups (RR 0.38, 95 % CI 0.07 to 2.17, I2 = 48 %) (Supplemental Figure 2).

4. Discussion

This systematic review evaluating the efficacy and safety of cryoanalgesia for the management of postoperative pain included 24 RCTs covering thoracic surgery, herniorrhaphy, nephrectomy, and tonsillectomy. Results from the majority of studies (13/24) indicate that cryoanalgesia can potentially provide better pain relief compared to comparator, except in herniorrhaphy and nephrectomy. Specific to thoracotomies, pain relief was associated with decreased opioid use when compared to intercostal nerve blocks, but not when compared to epidural analgesia. Reporting of adverse events was often inconsistent. Existing evidence suggests the potential for decreased nausea with the decrease in opioids.

Cryoanalgesia has been used for decades for chronic nerve pain as well as on surgically exposed nerves to provide postoperative pain relief, most commonly for thoracotomies [8,43]. The mechanism of action is based on the principle that when nerve tissues are cooled to between −20°C and −100°C, Wallerian degeneration (axon degeneration) distal to the lesion occurs, inhibiting nerve signalling for weeks to months as the axon regenerates [8]. More recently, the advent of ultrasound-guided percutaneous cryoanalgesia may increase its use in acute and postoperative pain control as it is safer, more precise, and surgically exposing the target nerve is not required [44].

There are distinct advantages with the use of cryoanalgesia compared to existing modalities, such as the administration of loco-regional analgesia or peripheral nerve blocks [10]. The most obvious benefit is the prolonged duration of analgesia ranging from weeks to months, although the duration appears to be variable depending on the length of the nerve distally from where the cryoanalgesia was applied [8]. Surprisingly, none of the included studies specifically assessed the duration of relief in their patients over time. Among available opioid-sparing agents, loco-regional blocks perhaps have the greatest benefits, whenever appropriate. This is because they can be selectively applied to a particular area of the body with no systemic side effects and they also act superiorly on pain with activity, which is functionally more important [45]. However, they are all limited by their duration of effect. Presently, the strategies to overcome this limitation requires the use of either continuous nerve blocks or the use of liposomal bupivacaine. However, both have inherent limitations, may not be available, and in the case of continuous blocks-require resources and trained personnel [[46], [47], [48]].

The potential for prolonged duration of action with cryoanalgesia may reduce readmissions and emergency room visits, apart from decreasing the risk of systemic morbidity [4,49]. Importantly, its opioid-sparing benefit can last after discharge, minimizing the need for opioid prescriptions post-discharge, which seems to be contributing to the opioid crisis. Other advantages of cryoanalgesia include its low cost, limited follow-up requirements, no risk of local anesthetic toxicity, and no need to carry around an infusion pump as one does with continuous peripheral nerve blocks [10]. However, drawbacks include the increased time required for administration, unpredictable duration of action, unclear association between application technique and duration of blockade, and somewhat limited number of surgical procedures during which it can be utilized [10].

To draw accurate conclusions about cryoanalgesia's efficacy and adverse effects in postoperative pain management, future studies should precisely describe the method of application, including the type of cryoprobe used, number of freeze cycles, and degree of nerve involvement and manipulation. Given the increased precision and theoretical safety, future studies should also evaluate ultrasound-guided percutaneous cryoanalgesia for postoperative pain and potentially acute pain in general. Finally, additional direct comparison studies with other postoperative pain management modalities such as regional analgesia would be useful.

Several limitations of this review should be acknowledged. Most studies had fewer than 50 participants per treatment arm, increasing the risk of small study bias [50]. Additionally, many studies were published over two decades ago and suffered from methodological limitations, such as not reporting the number of and reason for dropouts. Furthermore, many studies were heterogenous and provided only graphical data, often with no standard deviations, for pain-related outcomes. This heterogeneity and lack of useable data made it difficult to compare findings of the studies with each other and therefore, much of our analysis was descriptive in nature. Lastly, 14 of the included studies did not specify whether pain was measured at rest or with movement. It is important to differentiate between pain at rest and pain with movement as many current pain treatments differentially affect the two types of pain, and failure to distinguish the two threatens trial precision [51].

4.1. Conclusions

Cryoanalgesia is a technique of postoperative pain relief that can be potentially long acting, relatively inexpensive, and has minimal contraindications [10]. Existing evidence suggests that in patients having thoracotomies, cryoanalgesia can be associated with better pain relief and opioid reduction than intercostal nerve blocks, but not superior to epidural analgesia. Due to a lack of studies, its potential for other surgical populations is unknown and needs to be evaluated. Future studies should consider a larger sample size with appropriate comparators.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102689.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not obtained as this was a systematic review and meta-analysis of previously published studies.

Consent

N/A.

Author contribution

Rex Park, BHSc: Literature search, data extraction and analysis, drafting the article, final approval. Michael Coomber, BHSc: Literature search, data extraction and analysis, drafting the article, final approval. Ian Gilron, MD, MSc: Conception and study design, interpretation of study results, drafting the article, final approval Harsha Shanthanna, MD, PhD: Study supervision, conception and study design, data analysis, interpretation of study results, drafting the article, final approval.

Registration of research studies

-

1

Name of the registry: Prospero

-

2

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: CRD42020195702

-

3

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=195702

Guarantor

Harsha Shanthanna.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Gan T.J., Habib A.S., Miller T.E., White W., Apfelbaum J.L. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2014;30:149–160. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.860019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum J.L., Chen C., Mehta S.S., Gan T.J. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth. Analg. 2003;97:534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068822.10113.9e. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu C.L., Naqibuddin M., Rowlingson A.J., Lietman S.A., Jermyn R.M., Fleisher L.A. The effect of pain on health-related quality of life in the immediate postoperative period. Anesth. Analg. 2003;97:1078–1085. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000081722.09164.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breivik H. Postoperative pain management: why is it difficult to show that it improves outcome? Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 1998;15:748–751. doi: 10.1097/00003643-199811000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu C.L., Raja S.N. Treatment of acute postoperative pain. Lancet. 2011;377:2215–2225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R., Gordon D.B., de Leon-Casasola O.A. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American pain society, the American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and the American society of anesthesiologists' committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. J. Pain. 2016;17:131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilfeld B.M. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks: a review of the published evidence. Anesth. Analg. 2011;113:904–925. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182285e01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trescot A.M. Cryoanalgesia in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2003;6:345–360. PMID: 16880882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garibyan L., Tuchayi S.M., Wang Y. Neural selective cryoneurolysis with ice slurry injection in a rat model. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:185–194. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilfeld B.M., Finneran J.J. Cryoneurolysis and percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation to treat acute pain. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:1127–1149. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawber R.P. Cryosurgery: complications and contraindications. Clin. Dermatol. 1990;8:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(90)90073-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook D.K., Georgouras K. Complications of cutaneous cryotherapy. Med. J. Aust. 1994;161:210–213. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1994.tb127385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart R.H., Graham G.F. Cryo corner: a complication of cryosurgery in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1978;4:743–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1978.tb00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilfeld B.M., Gabriel R.A., Trescot A.M. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cryoneurolysis for treatment of acute pain: could cryoanalgesia replace continuous peripheral nerve blocks? Br. J. Anaesth. 2017;119:703–706. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raggio B.S., Barton B.M., Grant M.C., McCoul E.D. Intraoperative cryoanalgesia for reducing post-tonsillectomy pain: a systemic review. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2018;127:395–401. doi: 10.1177/0003489418772859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dworkin R.H., Turk D.C., Farrar J.T. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins J.P., Thomas J., Chandler J. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callesen T., Bech K., Thorup J. Cryoanalgesia: effect on postherniorrhaphy pain. Anesth. Analg. 1998;87:896–899. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199810000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khiroya R.C., Davenport H.T., Jones J.G. Cryoanalgesia for pain after herniorrhaphy. Anaesthesia. 1986;41:73–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1986.tb12709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmadnia H., Molaei M., Golparvar S. Effects of cryoanalgesia on post nephrectomy pain in kidney donors. Saudi. J. Kidney. Dis. Transpl. 2010;21:947–948. PMID: 20814139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson S.R., Purdie G.L. Reducing post-tonsillectomy pain with cryoanalgesia: a randomized controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1128–1131. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ba Y.-F., Li X.-D., Zhang X. Comparison of the analgesic effects of cryoanalgesia vs. parecoxib for lung cancer patients after lobectomy. Surg. Today. 2015;45:1250–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-1043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Q., Han Y., Cao W. Comparison of non-divided intercostal muscle flap and intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia treatments for post-oesophagectomy neuropathic pain control. Eur. J. Cardio. Thorac. Surg. 2013;43 doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs645. e64–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Momenzadeh S., Elyasi H., Valaie N. Effect of cryoanalgesia on post-thoracotomy pain. Acta Med. Iran. 2011;49:241–245. PMID: 21713735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwak M.S., Yang M., Hahm T.S., Cho H.S., Cho C.H., Song J.G. Effect of cryoanalgesia combined with intravenous continuous analgesia in thoracotomy patients. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 2004;19:74–78. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moorjani N., Zhao F., Tian Y., Liang C., Kaluba J., Maiwand M.O. Effects of cryoanalgesia on post-thoracotomy pain and on the structure of intercostal nerves: a human prospective randomized trial and a histological study. Eur. J. Cardio. Thorac. Surg. 2001;20:502–507. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sepsas E., Misthos P., Anagnostopulu M., Toparlaki O., Voyagis G., Kakaris S. The role of intercostal cryoanalgesia in post-thoracotomy analgesia. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2013;16:814–818. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma Y., Liu Y., Zuo J. Cryoanalgesia of intercostal nerves following thoracotomy: clinical trial based on animal experiment, Neural. Regen. Res. 2009;4:1083–1087. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2009.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller L.C., Salzer G.M., Ransmayr G., Neiss A. Intraoperative cryoanalgesia for postthoracotomy pain relief. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1989;48:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pastor J., Morales P., Cases E. Evaluation of intercostal cryoanalgesia versus conventional analgesia in postthoracotomy pain. Respiration. 1996;63:241–245. doi: 10.1159/000196553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keenan D.J., Cave K., Langdon L., Lea R.E. Comparative trial of rectal indomethacin and cryoanalgesia for control of early postthoracotomy pain. Br. Med. J. 1983;287:1335–1337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6402.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brichon P.Y., Pison C., Chaffanjon P. Comparison of epidural analgesia and cryoanalgesia in thoracic surgery. Eur. J. Cardio. Thorac. Surg. 1994;8:482–486. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roxburgh J.C., Markland C.G., Ross B.A., Kerr W.F. Role of cryoanalgesia in the control of pain after thoracotomy. Thorax. 1987;42:292–295. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.4.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miguel R., Hubbell D. Pain management and spirometry following thoracotomy: a prospective, randomized study of four techniques. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 1993;7:529–534. doi: 10.1016/1053-0770(93)90308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ju H., Feng Y., Yang B.-X., Wang J. Comparison of epidural analgesia and intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia for post-thoracotomy pain control. Eur. J. Pain. 2008;12:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz J., Nelson W., Forest R., Bruce D.L. Cryoanalgesia for post-thoracotomy pain. Lancet. 1980;1:512–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)92766-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joucken K., Michel L., Schoevaerdts J.C., Mayne A., Randour P. Cryoanalgesia for post-thoracotomy pain relief. Acta Anaesthesiol. Belg. 1987;38:179–183. PMID: 2889313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts D., Pizzarelli G., Lepore V., al-Khaja N., Belboul A., Dernevik L. Reduction of post-thoracotomy pain by cryotherapy of intercostal nerves. Scand. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1988;22:127–130. doi: 10.3109/14017438809105942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graves C.E., Moyer J., Zobel M.J. Intraoperative intercostal nerve cryoablation during the Nuss procedure reduces length of stay and opioid requirement: a randomized clinical trial. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019;54:2250–2256. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang M.K., Cho C.H., Kim Y.C. The effects of cryoanalgesia combined with thoracic epidural analgesia in patients undergoing thoracotomy. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:1073–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mustola S.T., Lempinen J., Saimanen E., Vilkko P. Efficacy of thoracic epidural analgesia with or without intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia for postthoracotomy pain. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011;91:869–873. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khanbhai M., Yap K.H., Mohamed S., Dunning J. Is cryoanalgesia effective for post-thoracotomy pain? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2014;18:202–209. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ilfeld B.M., Gabriel R.A., Trescot A.M. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous cryoneurolysis providing postoperative analgesia lasting many weeks following a single administration: a replacement for continuous peripheral nerve blocks?: a case report. Korean. J. Anesthesiol. 2017;70:567–570. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shanthanna H., Ladha K.S., Kehlet H., Joshi G.P. Perioperative opioid administration: a critical review of opioid-free versus opioid-sparing approaches. Anesthesiology. 2021;134:645–659. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joshi G., Gandhi K., Shah N., Gadsden J., Corman S.L. Peripheral nerve blocks in the management of postoperative pain: challenges and opportunities. J. Clin. Anesth. 2016;35:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton T.W., Athanassoglou V., Mellon S. Liposomal bupivacaine infiltration at the surgical site for the management of postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;2:Cd011419. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011419.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abildgaard J.T., Chung A.S., Tokish J.M., Hattrup S.J. Clinical efficacy of liposomal bupivacaine: a systematic review of prospective, randomized controlled trials in orthopaedic surgery. JBJS. Rev. 2019;7:e8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ip H.Y., Abrishami A., Peng P.W., Wong J., Chung F. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:657–677. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rücker G., Carpenter J.R., Schwarzer G. Detecting and adjusting for small-study effects in meta-analysis. Biom. J. 2011;53:351–368. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201000151. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srikandarajah S., Gilron I. Systematic review of movement-evoked pain versus pain at rest in postsurgical clinical trials and meta-analyses: a fundamental distinction requiring standardized measurement. Pain. 2011;152:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.