Introduction

The frequency of invasive fungal diseases (IFDs) continues to increase, producing significant morbidity and mortality in parallel with advances in medical care that tend to weaken host defense mechanisms.1,2 Unfortunately, the current episode of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) has just exposed the deficiencies of our health systems, particularly in Africa. Even though the African region was the least affected by this pandemic, the few serious cases confronted constituted a real challenge due to a lack of infrastructure and means of care. The health systems in Africa are generally fragile and are not prepared to face such epidemics. The number of qualified human resources, the availability of biomedical materials and drugs are the challenges of African countries.3

Globally, we are witnessing the emergence of pathologies requiring prolonged treatment during which patients receive broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and are subject to numerous invasive procedures such as the presence of a central venous catheter, which may promote direct vascular access of Candida spp. following previous colonization.4 These conditions, even temporary, can provoke the development of IFDs. This is the case with AIDS, cancers, especially blood cancers such as leukemia, hemodialysis, etc. Indeed, fungi are responsible for more than a billion cutaneous infections, more than 100 million mucous infections, 10 million serious allergies, and more than a million deaths each year. Global mortality due to fungal diseases (FDs) is higher than for malaria and breast cancer and is comparable to that from tuberculosis (TB) and HIV. These statistics show that FDs are a threat to human health and a major burden on healthcare budgets around the world.5

Antifungals – molecules used to treat FDs – fall into two categories. On the one hand, local antifungals or topicals are not absorbed orally, they are used locally for a local effect. On the other hand, systemic antifungals are absorbed orally or administered intravenously; they diffuse in the viscera.6 The latter group is divided into four classes: polyenes (amphotericin), azoles (fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, isavuconazole), echinocandins (caspofungin, anidulafungin, micafungin), and nucleoside analogs such as 5-fluorocytosine (flucytosine).7,8 For pharmacokinetic reasons, molecules such as griseofulvin (naturally occurring extract from Penicillium griseofulvum) or terbinafine (allylamines) are absorbed orally but are concentrated exclusively in the superficial skin layers. Thus, they are compared to topicals concerning therapeutic indications.6

Senegal is hardly an exception to this situation. Our country is also going through a socio-economic transition responsible for a medical transition. Risk factors for IFDs are present across the country; for example, the number of patients with HIV was estimated at 42,000 in 2019 with 63% on antiretroviral treatment.9 Other risk factors identified include leukemia, diabetes, asthma, and TB9–12 (Table 1). Thus, the Senegalese specialist will be increasingly confronted with the diagnosis and management of FDs. If the current antifungal arsenal in Senegal has molecules efficient for treating superficial FDs with molecules such as griseofulvin or fluconazole,13 many deep fungal diseases (DFDs) do not yet benefit from effective treatment with the absence or unavailability of antifungal drugs.14,15 Consequently, based on data from Aristide Le Dantec and Fann University Hospital Centers in Dakar, which are the only public health establishments with a medical mycology laboratory, the objective of this communication was to update the table of the main FDs diagnosed in Senegal and the antifungals available for their therapeutic management to draw attention to these infections increasingly diagnosed with the emergence of new opportunistic fungi.

Table 1.

Risk factors of invasive fungal diseases in Senegal, prevalence, and incidence of the principal underlying diseases.9–12.

| Risk factors of fungal diseases | Prevalence | Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | 0.5% (0.5–1.5) | 1300 per 1000 population (1000–1600) |

| TB | 0.08% (2019) | 140 cases/100.000 inhabitants from 2000 to 2016, 122 in 2017 and 118 in 2018 |

| Asthma* | 10% | 3% (children) and 6% (adults) |

| Diabetes | 5.1% | 771,579 people living with diabetes |

| Leukemia | 1.86%‡ | 145 cases (1.3%) in 2020 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 3.76‡ | 312 cases (2.8%) in 2020 |

Non-published data from the Albert Royer University Hospital for Children in Dakar presented during an academic session of the National Academy of Technical Sciences of Senegal (ANSTS).

Five-year prevalence (all ages): proportion per 100,000.

Analysis of the burden of fungal diseases in Senegal

Over the past two decades, the main publications mostly found on Pubmed and Google Scholar databases with ‘mycoses’ and ‘Senegal’ as keywords show the principal part of the epidemiology of FDs diagnosed in Dakar (capital of Senegal) which concentrates the only medical mycology laboratories in the country. These publications (Table 2) mainly concern superficial FDs such as tinea capitis,16–18 onychomycoses,19–21 intertrigos,22–24 among others,25–31 and subcutaneous FDs such as mycetomas32–35 and exceptionally chromomycosis.36 These superficial and subcutaneous FDs generally have an arsenal of antifungals that permit their management even if the latter treatment sometimes remains probabilistic.37 For DFDs, the reported publications essentially concern histoplasmosis,38,39 especially the African form often treated with disappointment,15 and cryptococcosis with which alternative treatment regimens have been adopted with a success rate estimated at 36.7%.40 Rare cases of pneumocystosis41 and aspergillosis/aspergilloma have been reported, treated by surgery without any adjunction of antifungal for the aspergilloses’ management, possibly due to antifungals unavailability.42–44

Table 2.

Principal fungal diseases (mycoses) diagnosed in Senegal.

| Frequency | Mycoses (fungal diseases) | Authors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Superficial | Tinea capitis | Ndiaye et al.,16 Kane et al.,17 Ndiaye et al.18 |

| Onychomycoses | Seck et al.,19 Sylla et al.,20 Diongue et al.21 | ||

| Intertrigos | Diongue et al.,22 Ndiaye et al.,23 Diongue et al.24 | ||

| Pityriasis versicolor, otitis and vulvovaginal candidiasis | Dioussé et al.,25 Diongue et al.,26 Dieng et al.,27 Sylla et al.28 | ||

| Subcutaneous | Mycetomas | Ndiaye et al.,32 Dieng et al.,33 Sow et al.,34 Badiane et al.,35 Diatta et al.37 | |

| Deep | Cryptococcosis | Sow et al.,40 Diallo Mbaye et al.,45 Manga et al.46 | |

| Pneumocystosis | Dieng et al.41 | ||

| Uncommon | Superficial | keratitis, endodontic candidiasis | Ndoye et al.,29 Diongue et al.,30 Ndiaye et al.31 |

| Subcutaneous | Chromomycosis | Develoux et al.36 | |

| Deep | Histoplasmosis | Ndiaye et al.,14 Diadie et al.,15 Diongue et al.,38 Dieng et al.39 | |

| Aspergillosis | Ndiaye et al.,42 Ade et al.,43 Ba et al.44 | ||

This relatively low frequency of DFDs aside from cryptococcosis,45,46 which represented more than half (50.8%) of the requests for diagnosis of DFDs in Fann University Hospital,47 would be mostly related to the weakness of the technical material and use of little sensitive biological tools of diagnosis.41 These diagnostic problems are corroborated by data from the infectious diseases department of this same institution. Indeed, according to a study carried out in this latter service on non-TB lower respiratory infections (LRI) in HIV patients between 2011 and 2015, out of the 255 patients with non-TB LRI, only three fungal etiologies (1.2%) were noted, including two cases due to unidentified yeasts. In addition, in 70.9% of cases, no etiology was found, which therefore motivated the administration of an antifungal (fluconazole) in 57.6% of patients and cotrimoxazole at a curative dose in 30.9%48 for preventing a probable pneumocystosis. These probabilistic treatments could contribute to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance given the already unavailability of antifungals. All the more so since, out of the 477 requests for the diagnosis of pneumocystosis received between 2005 and 2017 by the parasitology and mycology laboratory in Fann University Hospital, which hosts one of the few pneumology services in the public in Senegal, only 28 were positive corresponding to a hospital prevalence of 5.9%.47 Furthermore, in our microbiology laboratories in general and medical mycology laboratories in particular, the diagnosis is essentially based on conventional methods including direct microscopic examination and culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA), with identification of causative agents predominantly based on macroscopic and microscopic morphological characteristics. The only one matrix-associated laser desorption and ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)-based device accessible in the country is installed in ‘Hôpital Principal’ in Dakar, a hospital that does not specially perform mycological analyses, and accordingly, the database of this device does not include fungal species aside from the classic species of the genus Candida. The same is true for most private laboratories that have the Vitek 2 instrument.

Another problem that could explain this situation is the unequal distribution of the health system in Senegal. Indeed, as human resources, most of the infrastructure of the health system is based in Dakar. Except for health huts and level 2 hospitals, Dakar is the region with the best health infrastructure. Senegal has 11 level-3 hospitals, among them, 10 are in the Dakar region and the other in Touba, Diourbel region (185 km from Dakar).49 Therefore, to compensate, populaces in remote areas devote themselves to traditional medicine by attending traditional healers which sometimes delays treatment and leads to disastrous consequences. This is the case with patients with mycetoma. These patients are often received at an advanced stage of the disease with surgical excisions or amputation as the only treatment options. This is evidenced by the recent case of pulmonary metastasis of a knee mycetoma observed in Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital. The patient wasted a lot of time having their lesions treated by traditional practitioners at least for 10 years.50

The low knowledge of IFDs among physicians may also explain this situation. In fact, according to our mycological laboratory experience, almost only dermatologists systematically send requests for mycological analyzes. Apart from them, the other specialists only resort to the mycology laboratory in no-way-out-situations when they have explored all other possibilities. Moreover, a cross-sectional multicenter survey across seven tertiary hospitals in five geopolitical zones of Nigeria between June 2013 and March 2015 showed that only 0.002% (2/1046) of the respondents had a good level of awareness of IFDs.51

Evidence for unavailability of systemic antifungals in Senegal

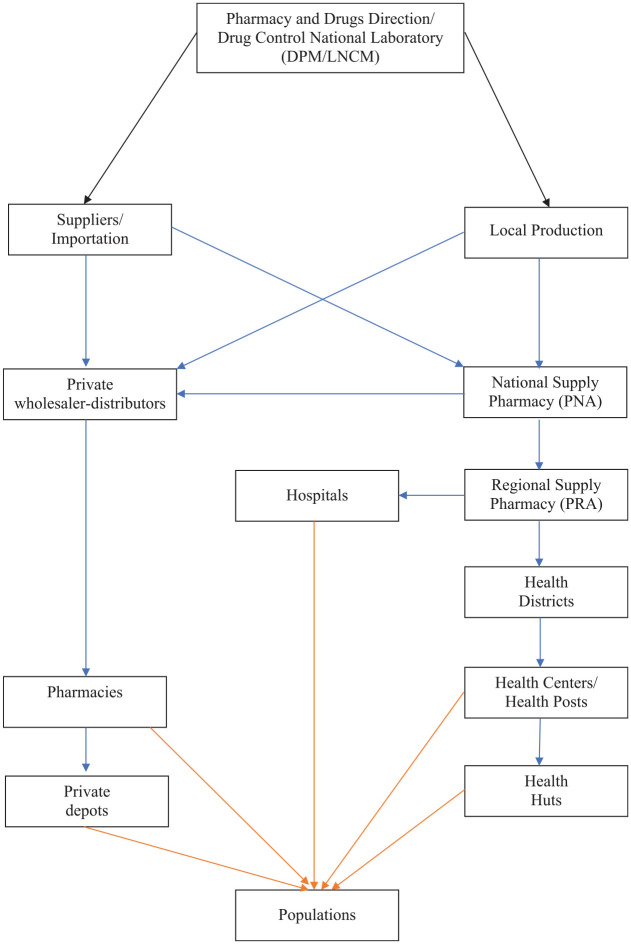

In Senegal, there are only three pharmaceutical industries that meet around 10–15% of needs and none of them produce systemic antifungals.52 According to the distribution circuit of drugs in Senegal (Figure 1),13 populations can only obtain drugs from two sources: health organizations and pharmacies.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the drug distribution circuit in Senegal.

Adapted from the National Essentials Drug, 2018 version.13

Black arrows represent regulation and control, blue arrows are for distributions and orange arrows are for delivery.

This distribution circuit is also applicable to hospital pharmacies according to an investigation carried out in Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital and Fann University Hospital on the flow of antifungals situation. Indeed, these hospital pharmacies can only obtain antifungals through the national supply pharmacy (NSP). Consequently, in the case of medical prescription of non-available antifungals in health facilities, patients should look for them in pharmacies that may have them in situ or order them via their commercial connections, connections that are only within the reach of a small group.

By compiling the list of essential drugs in Senegal and the list of antifungals available from two of the four drugs wholesaler distributions to pharmacies, antifungals available in Senegal are summarized in Table 3 with their indications.53

Table 3.

Antifungals available in Senegal with their medicinal forms and indications.

| INN | Dosage | Available forms | Indications53 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Griseofulvin | 250 mg | Tablet | Dermatophytosis |

| 500 mg | Tablet | ||

| Nystatin* | 500,000 IU | Tablet | Mucocutaneous, genital, digestive candidiasis, mixed vaginitis

(Candida and

Trichomonas) Geotrichosis Otomycosis (Aspergillus, Candida) Seborrheic dermatitis |

| 100,000 IU | Vaginal tablet | ||

| 100,000 IU | Oral solution | ||

| Amphotericin B* | 250 mg | Vaginal tablet | |

| 1000 µg/ml | Oral solution | ||

| Terbinafine | 250 mg | Tablet | Onychomycoses Extensive dermatophytosis |

| Fluconazole | 50 mg | Tablet | Oropharyngeal, esophageal and visceral candidiasis, cryptococcal meningitis |

| 100 mg | Tablet | ||

| 150 mg | Capsule | ||

| 200 mg | Tablet | ||

| 2 mg/ml | Injectable solution | ||

| 50 mg/5 ml | Oral solution | ||

| Econazole | 150 mg | Vaginal tablet | Cutaneous, genital and digestive candidiasis |

| 1% | Cream | ||

| 100 mg | Ovule | ||

| Clotrimoxazole | 0.05% | Cream | |

| 1% | Cream | Cutaneous candidiasis Dermatophytosis Pityriasis versicolor Non-dermatophytes superficial infections |

|

| 100 mg | Ovule | ||

| Isoconazole | 1% | Cream | |

| 2% | Fluid emulsion | ||

| Ciclopiroxolamine | 1% | Cream | |

| 1%, 8% | Spray | ||

| 1% | Powder | ||

| Miconazole | 2% | Cream |

On the list of essential medicines in Senegal but not available from suppliers.

INN, international non-proprietary name.

Thus, the remark is that only fluconazole is available as a systemic antifungal in Senegal, whereas this molecule has no activity on a large number of the fungi responsible for DFDs encountered in Senegal. First, fluconazole does not work against infections caused by Aspergillus spp.54 Then, regarding candidiasis, while Candida albicans is usually sensitive to antifungals comprising fluconazole, this is not the same for other non-albicans species. Candida krusei exhibits natural resistance to fluconazole while Candida glabrata has variable or even dose-dependent azole susceptibility.55 As in general, our laboratories only performed the germ tub test to distinguish C. albicans from non-albicans species,56 the probabilistic use of fluconazole could lead to therapeutic failure or selection of resistant strains, as already seen in immunosuppressed patients on chronic fluconazole prophylaxis.57

So, our country is lagging far behind, particularly at a time when the country is witnessing the emergence of pathologies such as renal failure and cancer, but also the development of the means implemented for their management such as hemodialysis centers or chemotherapy centers and even the establishment of a national organ donation committee responsible for regulating kidney transplantation.58 In our sub-region for example, four antifungal agents for IFDs (amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole) were licensed in Nigeria.51 Even better in north Africa, all classes of systemic antifungals (amphotericin B for polyenes, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole for azoles, caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin for echinocandins and flucytosine for nucleoside analogs) are available in Morocco (http://dmp.sante.gov.ma/) and Tunisia (http://www.dpm.tn/).

Conclusions/recommendations

It appears from this analysis that FDs are regularly diagnosed in Senegal. However, DFDs are maybe underestimated probably related to the weakness of the technical platform and consequently the use of insensitive biological diagnostic tools. Also, the few cases of DFDs diagnosed do not benefit from antifungal molecules for specific effective treatment. Therefore, the most recent technical approaches and the most effective therapies must be adopted for rapid diagnosis and better management of DFDs. Likewise, molecular identification techniques should be added to conventional methods. For antifungal availability, a network based on the directory of African pharmacy and drug directorates must be set up and run in collaboration with the national laboratory directorates for harmonization of procedures to reduce morbidity and mortality related to IFDs, especially in Africa. Once again, this will depend at all decision-making levels, on the ability to provide to relevant actors the means to know, recognize, and appropriately treat FDs, especially for DFDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following drug distribution companies: SODIPHARM and DUOPHARM in Senegal for providing them with their lists of marketed drugs. They are also thankful to hospital pharmacies staff in Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital and Fann University Hospital.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: Conception, design of the study, and drafting the article: Khadim Diongue; reviewing the article: Mamadou A Diallo, Mame C Seck, Mouhamadou Ndiaye, Aida S Badiane, Daouda Ndiaye D; final approval of the version to be submitted: all authors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical statement: Our study did not require an ethical board approval because it did not contain human or animal trials.

ORCID iD: Diongue K  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7033-1169

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7033-1169

Data availability: Data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Contributor Information

Khadim Diongue, Service of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Cheikh Anta Diop Avenue, Dakar, BO 3005, Senegal; Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

Mamadou Alpha Diallo, Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

Mame Cheikh Seck, Service of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal; Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

Mouhamadou Ndiaye, Service of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal; Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

Aida Sadikh Badiane, Service of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal; Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

Daouda Ndiaye, Service of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal; Laboratory of Parasitology and Mycology, Aristide Le Dantec University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal.

References

- 1.Freeman Weiss Z, Leon A, Koo S. The evolving landscape of fungal diagnostics, current and emerging microbiological approaches. J Fungi 2021; 7: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kung H-C, Huang P-Y, Chen W-T, et al. 2016 Guidelines for the use of antifungal agents in patients with invasive fungal diseases in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2018; 51: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Alliance for International Medical Action (ALIMA). COVID-19: Le système de santé des pays africains est très fragile et n’est pas prêt à faire face à cette pandémie. https://www.alima-ngo.org/fr/covid-19–le-systeme-de-sante-des-pays-africains-est-tres-fragile-et-n-est-pas-pret-a-faire-face-a-cette-pandemie- (accessed 19 April 2020).

- 4.Chabasse D, Pihet M, Bouchara J-P.Émergence de nouveaux champignons pathogènes en médecine: revue générale. Rev Fra Lab 2009; 416: 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gow NA, Netea MG.Medical mycology and fungal immunology: new research perspectives addressing a major world health challenge. Phil Trans R Soc B 2016; 371: 20150462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collège des Universitaires de Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales (CMIT). ePILLY trop 2016: Maladies infectieuses tropicales. Edition web mise à jour Août 2016. Alinéa Plus. www.infectiologie.com (2016; accessed 4 July 2021).

- 7.Van Daele R, Spriet I, Wauters J, et al. Antifungal drugs: what brings the future? Med Mycol 2019; 57: S328–S343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espinel-Ingroff A.Antifungal agents. In: Schmidt TM. (ed.) Encyclopedia of microbiology, 4th ed. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier, 2019, pp. 140–159. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS data. UNAIDS. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf (2019; accessed 4 July 2021). [PubMed]

- 10.Anonymous authors. National strategic plan to reduce human rights – related barriers to HIV, TB and malaria services: Senegal 2021–2025. https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/8d8916db7070b63/crg_humanrightssenegal2021-2025_plan_fr.pdf (accessed 4 July 2021).

- 11.World Health Organization (WHO). Country profiles for diabetes. https://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/senfr.pdf?ua=1 (2016; accessed 4 July 2021).

- 12.The Global Cancer Observatory (Globocan). Senegal. Globocan. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/686-senegal-fact-sheets.pdf (2020; accessed 4 July 2021).

- 13.Ministère de la Santé et de l’action Sociale. Liste nationale de médicaments et produits essentiels du Sénégal. Arrêté ministériel N° 016917/MSAS/DGS/DPM. https://www.dirpharm.net/images/sampledata/pdf/Liste_nationale.pdf (2018; accessed 28 January 2021).

- 14.Ndiaye D, Diallo M, Sene PD, et al. Histoplasmose disséminée à Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii au Sénégal. À propos d’un cas chez un patient VIH positif. J Mycol Med 2011; 21: 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diadie S, Diatta B, Ndiaye M, et al. Histoplasmose multifocale à Histoplasma capsulatum var. duboisii chez un Sénégalais de 22 ans sans immunodépression prouvée. J Mycol Med 2016; 26: 265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndiaye M, Diongue K, Seck MC, et al. Profil épidémiologique des teignes du cuir chevelu à Dakar (Sénégal). Bilan d’une étude rétrospective de six ans (2008–2013). J Mycol Med 2015; 25: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kane A, Ndiaye D, Niang SO, et al. Tinea in Senegal: an epidemiologic study. Int J Dermatol 2005; 44: 24–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ndiaye D, Sène PD, Ndiaye JL, et al. Teignes du cuir chevelu diagnostiquées au Sénégal. J Mycol Med 2009; 19: 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seck MC, Ndiaye D, Diongue K, et al. Profil mycologique des onychomycoses à Dakar (Sénégal). J Mycol Med 2014; 24: 124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sylla K, Tine RCK, Sow D, et al. Epidemiological and mycological aspects of onychomycosis in Dakar (Senegal). J Fungi (Basel) 2019; 5: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diongue K, Ndiaye M, Seck MC, et al. Onychomycosis caused by Fusarium spp. in Dakar, Senegal: epidemiological, clinical, and mycological study. Dermatol Res Pract 2017; 2017: 1268130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diongue K, Ndiaye M, Diallo MA, et al. Fungal interdigital tinea pedis in Dakar (Senegal). J Mycol Med 2016; 26: 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ndiaye M, Taleb M, Diatta BA, et al. Etiologie des intertrigos chez l’adulte: étude prospective de 103 cas. J Mycol Med 2017; 27: 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diongue K, Diallo MA, Ndiaye M, et al. Les intertrigos interorteils impliquant Fusarium spp. à Dakar (Sénégal). J Mycol Med 2018; 28: 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dioussé P, Ly F, Bammo M, et al. Pityriasis versicolor chez des nourrissons: aspect clinique inhabituel et rôle de la dépigmentation cosmétique par des corticoïdes chez la mère. Pan Afr Med J 2017; 26: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diongue K, Kébé O, Faye MD, et al. MALDI-TOF MS identification of Malassezia species isolated from patients with pityriasis versicolor at the Seafarers’ Medical Service in Dakar, Senegal. J Mycol Med 2018; 28: 590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dieng T, Sow D, Tine RC, et al. Otomycosis at Fann Hospital in Dakar (Senegal): prevalence and mycological study. J Mycol Mycological Sci 2020; 3: 000129. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sylla K, Sow D, Lakhe NA, et al. Candidoses vulvo-vaginales au laboratoire de Parasitologie-Mycologie du centre hospitalier universitaire de Fann, Dakar (Sénégal). Rev Cames Santé 2017; 5: 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ndoye Roth PA, Ba EA, Wane AM, et al. Problème diagnostique et thérapeutique de la kératite mycosique en zone intertropicale. Intérêt de l’usage local de la polividone iodée. J Fr Ophtalmol 2006; 29: el9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diongue K, Sow AS, Nguer M, et al. Kératomycose à Fusarium oxysporum traitée par l’association de la povidone iodée en collyre et du fluconazole per os. J Mycol Med 2015; 25: e134–e137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ndiaye D, Diongue K, Bane K, et al. Recherche de levures dans les primo-infections endodontiques et étude de leur sensibilité à une désinfection à l’hypochlorite de sodium à 2.5%. J Mycol Med 2016; 26: 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ndiaye D, Ndiaye M, Sène PD, et al. Mycétomes diagnostiqués au Sénégal de 2008 à 2010. J Mycol Med 2011; 21: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dieng MT, Sy MH, Diop BM, et al. Mycetoma: 130 cases. Ann Dermatol Venerol 2003; 130: 16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sow D, Ndiaye M, Sarr L, et al. Mycetoma epidemiology, diagnosis management, and outcome in three hospital centres in Senegal from 2008 to 2018. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0231871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badiane AS, Ndiaye M, Diongue K, et al. Geographical distribution of mycetoma cases in Senegal over a period of 18 years. Mycoses 2020; 00: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Develoux M, Dieng MT, Ndiaye B, et al. Chromomycose à Exophiala spinifera en Afrique sahélienne. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2006; 133: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diatta BA, Ndiaye M, Sarr L, et al. Un mycétome fongique tumoral dorsal: intérêt de la chirurgie large associée à la terbinafine. J Mycol Med 2014; 24: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diongue K, Diallo MA, Badiane AS, et al. Champignons non dermatophytiques et non candidosiques isolés au CHU Le Dantec de Dakar en 2014: étude épidémiologique, clinique et mycologique. J Mycol Med 2015; 25: 181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dieng T, Massaly A, Sow D, et al. Amplification of blood smear DNA to confirm disseminated histoplasmosis. Infection 2017; 45: 687–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sow D, Tine RC, Sylla K, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis in Senegal: epidemiology, laboratory findings, therapeutic and outcome of cases diagnosed from 2004 to 2011. Mycopathologia 2013; 176: 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dieng Y, Dieng T, Sow D, et al. Diagnostic biologique de la pneumonie à Pneumocystis au centre hospitalier universitaire de Fann, Dakar, Sénégal. J Mycol Med 2016; 26: 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ndiaye M, Maiga S, Nao EEM, et al. Aspergillose sinusienne invasive pseudotumorale: à propos de deux cas. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac Chir Orale 2015; 116: 372–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ade SS, Touré NO, Ndiaye A, et al. Aspects épidémiologiques, cliniques, thérapeutiques et évolutifs de l’aspergillome pulmonaire à Dakar. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires 2011; 28: 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ba PS, Ndiaye A, Diatta S, et al. Résultats du traitement chirurgical de l’aspergillome pulmonaire à Dakar. Médecine et Santé Tropicales 2015; 25: 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diallo Mbaye K, Lakhe NA, Sylla K, et al. Cryptococcose neuro-méningée: mortalité et facteurs associés au décès chez les patients hospitalisés au service des maladies infectieuses du CHNU de Fann. Médecine d’Afrique Noire 2018; 65: 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manga NM, Cisse-Diallo VMP, Dia-Badiane NM, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with positive cryptococcal antigenemia among HIV infected adult hospitalized in Senegal. Revue Tunisienne d’Infectiologie 2016; 10: 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Touré F.Profil épidémiologique et mycologique des infections fongiques profondes diagnostiquées au CHNU de Fann de 2005 à 2017. Thèse Pharmacie 2018; 30: 114. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawson ATD, Diop Nyafouna SA, Cissé VMP, et al. Épidémiologie, diagnostic et traitement des infections respiratoires basses non tuberculeuses chez les PVVIH au service des maladies infectieuses du Centre national hospitalier universitaire (CHNU) de Fann (Dakar-Senegal). RAFMI 2018; 5: 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie (ANSD). Situation économique et sociale du Sénégal en. http://www.ansd.sn/ressources/ses/chapitres/4-SES-2015Sante.pdf (2015; accessed 3 July 2021).

- 50.Sarr L, Diouf A, Diongue K, et al. Métastase pulmonaire d’un mycétome du genou au Sénégal. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 2019; 112: 129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oladele R, Otu AA, Olubamwo O, et al. Evaluation of knowledge and awareness of invasive fungal infections amongst resident doctors in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2020; 36: 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anonymous authors. Evaluation du secteur pharmaceutique au Sénégal: Rapport d’enquête. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/coordination/senegal_pharmaceutical.pdf (accessed 3 July 2021).

- 53.Contet-Audonneau N, Schmutz JL.Antifongiques et mycoses superficielles. Rev Fra Lab 2001; 332: 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html (2021; accessed 3 July 2021).

- 55.Alfouzan W, Dhar R, Ashkanani H, et al. Species spectrum and antifungal susceptibility profile of vaginal isolates of Candida in Kuwait. J Mycol Med 2015; 25: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diongue K, Mané MT, Diallo MA, et al. MALDI-TOF MS identification and antifungal susceptibility of Candida strains isolated from vulvovaginal candidiasis by the AST-YS08® Card with Vitek 2® in Dakar, Senegal. J Microbiol Antimicrob 2020; 12: 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dignani MC, Solomkin JS, Anaissie EJ.Candida. In: Dismukes WE, Pappas PG, Sobel JD. (eds) Clinical mycology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Décret de la loi N° 2015-22 du 08 décembre 2015 relative au don, prélèvement et à la transplantation d’organes et aux greffes de tissus humains. Signé le 30 avril 2019. http://www.dri.gouv.Sn/sites/default/files/LOI/2015/201522.pdf (accessed 19 April 2020).