The poor health of Black men in the United States has been an enigma, hidden in plain sight, for more than 100 years.1 Although Black men’s poor health is well documented, few research or policy frameworks exist to explain this finding. In this commentary, we use syndemics2 to explain why Black men in the United States are dying disproportionately from COVID-19 and to guide a framework for efforts to mitigate their risk of dying from COVID-19. Syndemics are defined as 2 or more epidemics interacting synergistically in ways that exacerbate health consequences because of their interaction. The syndemics approach helps to identify how the clustering of structural forces precipitates clustering of disease in specific populations, moving beyond the assumption that these phenomena are separate or coincidental.3 This framework can be used to guide programmatic and policy initiatives and research priorities to improve Black men’s health and reduce disparities in COVID-19 mortality.

Black Men’s COVID-19 Risk

Although COVID-19 data in the United States have not been routinely disaggregated to document epidemiologic patterns by race/ethnicity and sex simultaneously,4 data from the United Kingdom have shown that Black men have a higher COVID-19 death rate than any other race/ethnicity by sex group in England and Wales.5,6 The Office of National Statistics in England and Wales stated that the COVID-19 death rates of Black men of African background were 2.5 times higher than those of White men.5,6 The United Kingdom Office of National Statistics explained that race/ethnicity and gender differences were not caused by preexisting conditions but by demographic and socioeconomic factors or occupational exposure.5,6

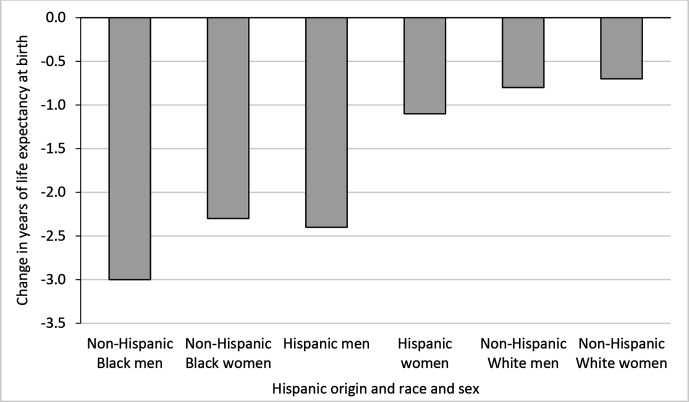

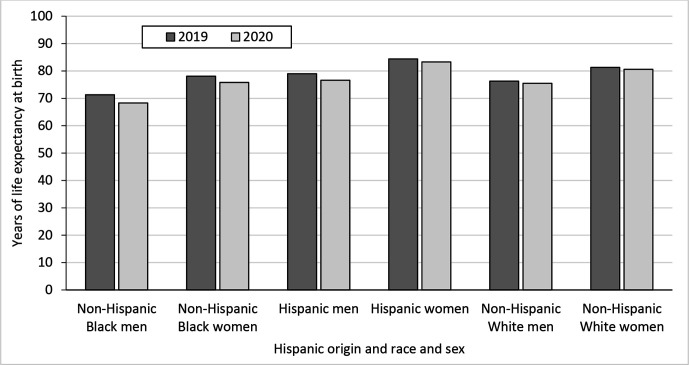

Similarly, provisional life expectancy estimates from February 2021 suggest that Black men had the greatest decline in life expectancy from 2019 to 2020 (3.0 years) (Figure 1).1,7 This decline is more than half of a year greater than the next closest groups—Hispanic men (−2.4 years) and Black women (−2.3 years). In 2019, Black men already had the shortest life expectancy of any racial/ethnic and sex group (71.3 years) (Figure 2). If this difference holds for the full year, Black men’s life expectancy in 2020 will have dropped to be almost as low as it was in 2000 (68.2 years1). And yet, these findings have not warranted explicit programmatic or policy intervention. Black men’s health and mortality remain hidden in plain sight. Gravlee8 argues: “The need for better data remains. But data alone are not enough. We also need an explicit conceptual framework to know what the numbers mean, shape the questions researchers ask, and direct attention to appropriate public health and policy responses.” We propose a syndemics approach to help solve this problem.

Figure 1.

Change in life expectancy at birth in years, by Hispanic origin, race, and sex: United States, 2019-2020. Data source: Arias et al.7

Figure 2.

Life expectancy at birth, by Hispanic origin, race, and sex: United States, 2019 and 2020. Data source: Arias et al.7

A Syndemics Approach to Black Men’s COVID-19 Mortality

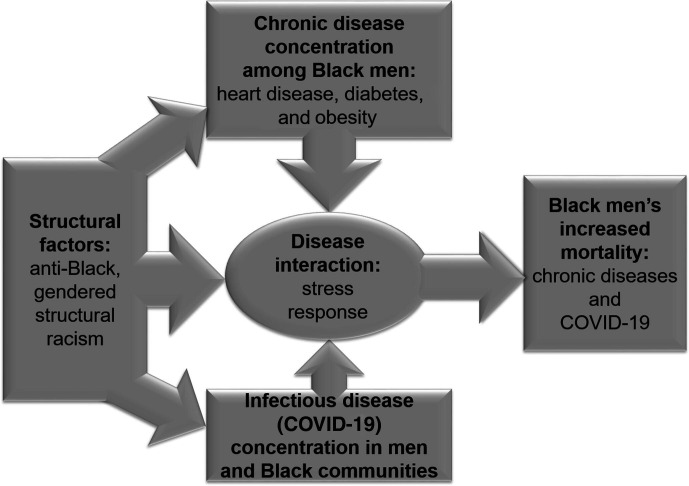

Singer and Clair2 define a syndemic as 2 or more epidemics interacting synergistically in ways that exacerbate health consequences because of their interaction with one another and with structural factors. The goal of a syndemics approach is to expand, enrich, and reframe determinants of health in ways that facilitate tailored population health and policy interventions.9 The 3 pillars of a syndemics approach are disease concentration, disease interaction, and structural forces that underlie these factors.10 Thus, we argue that Black men’s disproportionate risk of COVID-19 mortality may be because of the clustering and concentration of heart disease and obesity among Black men and the clustering and concentration of COVID-19 among men and in Black communities (Figure 3).4,11 The immune responses associated with being obese and having hypertension are activated and exacerbated by chronic stress and biological aging processes that are rooted in structural racism.12,13 The confluence of these factors increases Black men’s risk of dying from COVID-19 and other factors.14

Figure 3.

Syndemic approach to Black men’s mortality risk during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Describing the structural factors as anti-Black, gendered structural racism highlights the importance of using an intersectional approach to understand how structural factors affect specific populations.

Disease Concentration

Heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic diseases are preexisting conditions that exacerbate one’s risk of COVID-19 mortality.4,8 Heart disease is the leading cause of death among Black men in the United States.15 Almost three-fifths (58.3%) of Black men aged ≥20 have hypertension, and Black men are at least 1.5 times more likely than White men to have hypertension.16 Black men develop risk factors for hypertension and hypertension-related conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease) earlier than White men, and Black men have a higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension than White men.17,18

Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latinx workers are more likely than White workers to have jobs or living conditions that increase their risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.19-21 In addition, men tend to have lower rates than women of hand washing, social distancing, wearing face masks, and effectively and proactively seeking medical help.22-26 The stress of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated biological aging processes and resulted in a rise in rates of smoking, unsafe sex, alcohol use, substance abuse, suicidal ideation, and suicide.11 These behaviors all have historically been found to be higher among men than among women, and each behavior is a gendered strategy for men to cope with stress.26-32

Stress process models highlight how stressors are identity relevant, meaning they involve damages or losses to highly valued identities.33 Chronic racism-related stress fuels accelerated biological aging—weathering—that leads to wear and tear on body organs and inflammatory and immune systems. Racism-related stress is associated with health-related outcomes and physiological well-being such as hypertension,34-36 depressive symptoms,37 cigarette smoking,38 and alcohol use.39

Disease Interaction

Globally, more men than women have died from COVID-19.4,23 One of the key biological mechanisms linking sex and COVID-19 mortality is inflammation from the immune response to stress.14,23,40-42 The sources of weathering and types of racialized and gendered stressors that lead to this response are described later in this commentary. COVID-19 disease is caused by SARS-CoV-2, which binds directly to the host cell surface. The virus uses the SARS-CoV-2 receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and leads to inflammation-derived processes causing multi-organ injury or failure. ACE2 is an enzyme produced by the X chromosome that is present in the lungs, prostate, and testes; therefore, ACE2 is more highly expressed among males than among females.43,44 Males have 1 X chromosome and a single form of ACE2, whereas females have 2 X chromosomes, each producing a different form of ACE2.4,14,44 Because males have only 1 form of ACE2, if the virus can unlock a male’s ACE2, it has access to every cell in which the enzyme is present; in women, however, the virus would have to unlock the 2 forms of ACE2 from each X chromosome to have the same effect.44 Consequently, it may be easier for men to contract COVID-19 than for women to contract COVID-19; once infected, men may have less capacity than women to counter the damaging effects of the virus.44

The ACE2 receptor also plays a role in increasing blood pressure, and elevated ACE2 levels have been observed among people who smoke, people who are obese, and men with heart failure.4,45 Black men have the highest rate of smoking and the highest incidence of cigarette-smoking–attributable cancer of any racial/ethnic group by sex.46,47

Black women have higher rates of hypertension than Black men,48 but Black men have a higher rate of abdominal obesity (central adiposity) than Black women.48,49 Most studies find that adverse consequences of obesity are more strongly associated with central adiposity (a waist circumference >102 cm) than non-central obesity,50 particularly among Black adults. After Hispanic men, Black men have the second-highest rate of obesity among men51,52 and the highest rate of grade 3 obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2) among men.52 Thus, because the ACE2 receptor is more highly expressed among people who smoke or who are obese, and Black men have disproportionately high rates of both smoking and obesity, they may be at greater risk for COVID-19 infections and complications than women or men in other racial/ethnic groups.

Structural Factors

Structural factors—the policies and practices that create underlying social conditions that lead to disease concentration, clustering, and interaction—are the third pillar of a syndemics approach.53 Structural racism is a useful frame for these factors because it reflects the totality of ways that ideologies of inherent racial inferiority of socially defined groups (ie, races) create ranking or a caste system that differentially allocates societal resources and advantage.54-56 Structural racism illustrates how ideologies of inherent racial inferiority (ie, cultural racism57,58) operate through mutually reinforcing sectors of society (eg, health care, housing, education, criminal justice). These ideologies and sectors combine in ways that determine population-level patterns of health and well-being (ie, the experience of health, happiness, and prosperity) and concentrate and exacerbate chronic stressors in Black men’s lives in ways that lead to weathering during the lifecourse.54-56

An Intersectional Basis for Black Men’s Disproportionate COVID-19 Mortality

Similar to the limitations of presenting data by race/ethnicity or gender, describing the structural factors that shape Black men’s lives and health requires precision.59,60 We argue that a precise term capturing the structural factors that lead to weathering and that shape Black men’s COVID-19 mortality is anti-Black, gendered structural racism, and we use intersectionality as a framework to make this case. In coining the term, legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw60 argues that intersectionality is a strategy to map the intersections of race and gender in ways that disrupt the tendency to see race and gender as separable structures, when in fact they are intertwined.61 Crenshaw’s intersectionality is a unique structural recipe that helps us to explicitly name what and why the structural processes and diseases cluster within a population defined by age, race/ethnicity, gender, and national context.62,63

Crenshaw organizes intersectionality into structural, political, and representational intersectionality.60 Structural intersectionality highlights how Black men’s health and well-being are shaped by factors that differ qualitatively from Black women, White men, and others. When compared with other men and Black women, Black men may experience more intense discrimination because their social interactions tend to be based on a range of negative race- and gender-based stereotypes that characterize Black men as having fundamental constitutional weaknesses that make them prone to hostility, criminality, violence, and other antisocial behaviors.64-66 Some research has shown that Black men experience more daily indignities and microaggressions than Black women.67

Structural intersectionality

Structural intersectionality also helps to explain why Black men are more likely than any other race/ethnicity by sex group to be targeted, profiled, incriminated, investigated, unjustly committed, harshly sentenced, and imprisoned for crimes.68,69 Characterizations of Black men as violent, delinquent, or troublemakers historically have been used to vindicate the use of deadly force against them, even when unarmed, as in the case of George Floyd and others.70-72 In the United States, Black men are more than twice as likely as White men and more than 5 times as likely as Hispanic men to be imprisoned.73 Because Black men are disproportionately incarcerated, and prisons are one of the institutions with a particularly high number of COVID-19 cases, Black men are also being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 through this institutional context.74-76

Political intersectionality

Political intersectionality explains how our national politics marginalize Black men in the US response to COVID-19.60 Political intersectionality also helps to explain the invisibility and political ambivalence to Black men’s health in general and COVID-19 mortality in particular. Men’s health equity emerged from the need to focus on the health and well-being of Black men and others who are at the margins of the men’s health and health equity research agendas.62,77 Braveman78 argues that “the gender disparity in life expectancy is, albeit an important public health issue, not an appropriate health disparities issue, because in this particular case it is the a priori disadvantaged group—women—who experiences better health.” The Healthy People 2020 definition of health disparities, for example, explicitly included the notion that disparities refer to populations whose health is worse based on some social disadvantage or (single) characteristics historically linked to discrimination79; the definition of disparities did not apply to Black men. Regarding political action and policy agendas, because they are perceived as advantaged because of their gender but disadvantaged because of their race/ethnicity,80 Black men rarely receive explicit funding, programming, or policies beyond what was presumed to be gender neutral and beneficial to all Black Americans.

Representational intersectionality

Representational intersectionality centers the cultural construction and representation of Black men in explaining both the ways in which images of Black men are created and reproduced and how contemporary narratives explaining determinants of COVID-19 mortality marginalize Black men.60,66 From a syndemics perspective, these structural factors concentrate obesity and heart disease in Black men and create stressful life circumstances that activate immune responses. These experiences may explain the enigmatic findings that socioeconomic status is positively related to stress and suicide among Black men, negatively associated with stress among Black women, and negatively associated with suicide among White men.81 Black men’s experiences persist in “the white space,” or predominantly White neighborhoods, workplaces, courthouses, and other places where Black men are typically absent, not expected, or marginalized when present.82 As a condition of their existence and as a requirement of upward mobility, Black men who are employed in jobs with high social status—physicians, lawyers, bankers, or engineers—must navigate heightened visibility and increased performance pressure that exacerbate the stress and tension that already come from being a numerical minority.80,83

Discussion

For 120 years, the National Center for Health Statistics has documented that non-Hispanic Black men have a shorter life expectancy than any other race/ethnicity by gender group,1,7 with the possible exception of Native American men. In 1985, The Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health, also known as The Heckler Report, documented Black men’s shorter life expectancy and other health outcomes relative to other groups of men and women.84-86 Thirty years ago, McCord and Freeman87 shocked the medical community when they found that Black men in Harlem were less likely than men in Bangladesh to reach age 65, the age at which many workers expect to retire. Fifteen years ago, Satcher and colleagues88 found that the Black–White gap in mortality worsened for Black adults in large part because of the mortality rates of Black men aged ≥35. In 2018, amid findings that life expectancy in the United States declined 3 years in a row, Bilal and Diez-Roux89 attributed the change to Black men, the only group whose mortality increased during that time. Nevertheless, these data, not Black men’s COVID-19 mortality, warrant federal programs or policies to improve the health and well-being of Black men.

Black men’s disproportionate COVID-19 mortality rate was frustrating because it was predictable and modifiable. Our current strategies for outbreak mitigation and health promotion often mask critical differences by age, occupation, place (eg, neighborhood, region of the country), sexual orientation, nativity, immigration status, and other factors. Although it is impractical to disaggregate data by all these factors, our framework offers a useful approach to determine what factors data should be disaggregated by, in what contexts, and for what issues.90

Syndemics is not without its critics; the approach has remained largely theoretical.10 It has been difficult to optimize syndemics in part because of the challenges inherent in measurement. Ideal strategies or tools to measure each component of a syndemics approach across levels of conceptualization (eg, biological, behavioral, policy, structural) are not always available.91,92 Finding convincing empirical evidence of disease interaction beyond rigorous anthropological studies is challenging. Future research should sharpen empirical predictions based on a syndemics approach so that investigators can have specific, testable hypotheses.93

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to reduce COVID-19 mortality among Black men and to more effectively pursue health equity:

Use the integrated syndemics/intersectional approach to inform simulation models of the potential effects of health and public policy changes.

Because health promotion and disease prevention efforts are data driven, regularly disaggregate data by race/ethnicity and gender to better inform health and public programming and policy.

Train health professionals to realize that racism and other social determinants of health are not monolithic; racism and other social determinants of health have and continue to operate differently within and across populations (eg, gendered, anti-Black, anti-Asian, anti-immigrant).

Use Crenshaw’s intersectional approach to teach physicians and other health professionals how eugenics, unethical experimentation (eg, Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,94 the salt–slavery hypothesis, and other historical studies and belief systems) reflect not only scientific racism but broader cultural beliefs about the meaning of race and explanations for racial inequities in health.

Apply the integrated syndemics/intersectional approach to populations in other countries that have unique histories of racism, strategies of categorizing their population,95 and approaches to disaggregating data.

Conclusion

COVID-19 research and other research and policy often have treated Black men—not gendered racism, anti-Black racism, structural racism, inequitable policies, or the intersection of these factors—as the problem to be solved.64,96-99 Consequently, a need exists for a framework to help explain why Black men are disproportionately affected by myriad poor health outcomes and may have an increased mortality risk from COVID-19, heart disease, and diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article was initially drafted and submitted for publication when Dr. Griffith was a faculty member at Vanderbilt University.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Holliday is an employee of the American Medical Association (AMA), but the opinions expressed herein are his own and should not be interpreted as AMA policy.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article was supported in part by the American Cancer Society (RSG-15-223-01-CPPB), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (5U54MD010722-02), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (75532).

ORCID iD

Derek M. Griffith, PhD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0018-9176

References

- 1.Arias E., Xu J. United States life tables, 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(7):1-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer M., Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17(4):423-441. 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendenhall E., Singer M. What constitutes a syndemic? Methods, contexts, and framing from 2019. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2020;15(4):213-217. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith DM., Sharma G., Holliday CSet al. Men and COVID-19: a biopsychosocial approach to understanding sex differences in mortality and recommendations for practice and policy interventions. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E63. 10.5888/pcd17.200247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntyre N. Black men in England three times more likely to die of COVID-19 than White men. Guardian. June 19, 2020. Accessed May 9, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/jun/19/black-men-england-wales-three-times-more-likely-die-covid-19-coronavirus

- 6.Coronavirus: Black men have higher coronavirus death rate than anyone else in England and Wales . Sky News. October 16, 2020. Accessed December 9, 2020. https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-black-men-have-higher-coronavirus-death-rate-than-anyone-else-in-england-and-wales-12105344

- 7.Arias E., Tejada-Vera B., Ahmad F. Provisional life expectancy estimates for January through June, 2020. National Vital Stat Rapid Release 2021;(010):1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravlee CC. Systemic racism, chronic health inequities, and COVID-19: a syndemic in the making? Am J Hum Biol. 2020;32(5):e23482. 10.1002/ajhb.23482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willen SS., Knipper M., Abadía-Barrero CE., Davidovitch N. Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):964-977. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai AC., Mendenhall E., Trostle JA., Kawachi I. Co-occurring epidemics, syndemics, and population health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):978-982. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30403-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JA., Griffith DM., White Aet al. COVID-19, equity and men’s health: using evidence to inform future public health policy, practice and research responses in pandemics. Int J Mens Soc Community Health. 2020;3(1):e48-e64. 10.22374/ijmsch.v3i1.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padgett DA., Glaser R. How stress influences the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(8):444-448. 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00173-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruce MA., Griffith DM., Thorpe RJ Jr. Stress and the kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):46-53. 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma G., Volgman AS., Michos ED. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep. 2020;2(9):1407-1410. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Leading causes of death—males—non-Hispanic Black—United States, 2017. November 20, 2019. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/lcod/men/2017/nonhispanic-black/index.htm

- 16.Carnethon MR., Pu J., Howard Get al. Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heffernan KS., Jae SY., Wilund KR., Woods JA., Fernhall B. Racial differences in central blood pressure and vascular function in young men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(6):H2380-H2387. 10.1152/ajpheart.00902.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce MA., Beech BM., Griffith DM., Thorpe RJ Jr. Weight status and blood pressure among adolescent African American males: the Jackson Heart KIDS Pilot Study. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):305-312. 10.18865/ed.25.3.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webb Hooper M., Nápoles AM., Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467. 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowkwanyun M., Reed AL Jr. Racial health disparities and COVID-19—caution and context. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):201-203. 10.1056/NEJMp2012910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams DR., Cooper LA. COVID-19 and health equity—a new kind of “herd immunity”. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2478-2480. 10.1001/jama.2020.8051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia S., Albaghdadi MS., Meraj PMet al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(22):2871-2872. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker P., White A., Morgan R. Men’s health: COVID-19 pandemic highlights need for overdue policy action. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1886-1888. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31303-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewig C. Gender, masculinity, and COVID-19. Gender Policy Report. April 1, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://genderpolicyreport.umn.edu/gender-masculinity-and-covid-19

- 25.Smith JA., Watkins DC., Griffith DM., Richardson N., Adams M. Strengthening policy commitments to equity and men’s health. Int J Mens Soc Community Health. 2020;3(3):e9-e10. 10.22374/ijmsch.v3i3.54 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandello JA., Bosson JK., Lawler JR. Precarious manhood and men’s health disparities. In: Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Thorpe RJ Jr., eds.Men’s Health Equity: A Handbook. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2019:27-41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffith DM., Thorpe RJ Jr. Men’s physical health and health behaviors. In: Wong YJ., Wester SR., eds.APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities. American Psychological Association; 2016:709-730. 10.1037/14595-032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandello JA., Bosson JK. Hard won and easily lost: a review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychol Men Masc. 2013;14(2):101-113. 10.1037/a0029826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson JS., Knight KM. Race and self-regulatory health behaviors: the role of the stress response and the HPA axis in physical and mental health disparities. In: Schaie KW., Carstensen LL., eds.Social Structure, Aging, and Self-regulation in the Elderly. Springer; 2006:189-239. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin LA., Neighbors HW., Griffith DM. The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: analysis of the national comorbidity survey replication. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1100-1106. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliffe JL., Phillips MJ. Men, depression and masculinities: a review and recommendations. J Mens Health. 2008;5(3):194-202. 10.1016/j.jomh.2008.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watkins DC. Depression over the adult life course for African American men: toward a framework for research and practice. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(3):194-210. 10.1177/1557988311424072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLeod JD. The meanings of stress: expanding the stress process model. Soc Ment Health. 2012;2(3):172-186. 10.1177/2156869312452877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicken MT., Lee H., Morenoff J., House JS., Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in hypertension prevalence: reconsidering the role of chronic stress. In: De Maio F., Shah RC., Mazzeo J., Ansell DA., eds.Community Health Equity: A Chicago Reader. University of Chicago Press; 2019:173. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alang S., McAlpine D., McCreedy E., Hardeman R. Police brutality and Black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662-665. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duru OK., Harawa NT., Kermah D., Norris KC. Allostatic load burden and racial disparities in mortality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(1-2):89-95. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30120-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wheaton FV., Thomas CS., Roman C., Abdou CM. Discrimination and depressive symptoms among African American men across the adult lifecourse. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(2):208-218. 10.1093/geronb/gbx077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker LJ., Hunte H., Ohmit A., Furr-Holden D., Thorpe RJ Jr. The effects of discrimination are associated with cigarette smoking among Black males. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(3):383-391. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1228678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pittman DM., Brooks JJ., Kaur P., Obasi EM. The cost of minority stress: risky alcohol use and coping-motivated drinking behavior in African American college students. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2019;18(2):257-278. 10.1080/15332640.2017.1336958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng Y., Wu P., Lu Wet al. Sex-specific clinical characteristics and prognosis of coronavirus disease-19 infection in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study of 168 severe patients. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(4):e1008520. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu Z., McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-1242. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter LA., McGregor AJ. Sex- and gender-specific observations and implications for COVID-19. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(3):507-509. 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li W., Moore MJ., Vasilieva Net al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450-454. 10.1038/nature02145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White A., Kirby M. COVID-19: biological factors in men’s vulnerability. Trends Urol Mens Health. 2020;11(4):7a-9a. 10.1002/tre.757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sama IE., Ravera A., Santema BTet al. Circulating plasma concentrations of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in men and women with heart failure and effects of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone inhibitors. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(19):1810-1817. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jemal A., Miller KD., Ma Jet al. Higher lung cancer incidence in young women than young men in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1999-2009. 10.1056/NEJMoa1715907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lortet-Tieulent J., Kulhánová I., Jacobs EJ., Coebergh JW., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A. Cigarette smoking-attributable burden of cancer by race and ethnicity in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(9):981-984. 10.1007/s10552-017-0932-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Go AS., Mozaffarian D., Roger VLet al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6-e245. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okosun IS., Choi S., Dent MM., Jobin T., Dever GE. Abdominal obesity defined as a larger than expected waist girth is associated with racial/ethnic differences in risk of hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15(5):307-312. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGill HC., McMahan CA., Herderick EEet al. Obesity accelerates the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in young men. Circulation. 2002;105(23):2712-2718. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000018121.67607.CE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoue Y., Qin B., Poti J., Sokol R., Gordon-Larsen P. Epidemiology of obesity in adults: latest trends. Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7(4):276-288. 10.1007/s13679-018-0317-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flegal KM., Kruszon-Moran D., Carroll MD., Fryar CD., Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284-2291. 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poteat T., Millett GA., Nelson LE., Beyrer C. Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among Black communities in America: the lethal force of syndemics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:1-3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bailey ZD., Krieger N., Agénor M., Graves J., Linos N., Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams DR., Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(4):75-90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffith DM. Well-being in Healthy People 2030: a missed opportunity. Health Educ Behav. 2021;48(2):115-117. 10.1177/1090198121997744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cogburn CD. Culture, race, and health: implications for racial inequities and population health. Milbank Q. 2019;97(3):736-761. 10.1111/1468-0009.12411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffith DM., Johnson J., Ellis KR., Schulz AJ. Cultural context and a critical approach to eliminating health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1):71-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffith DM. An intersectional approach to men’s health. Am J Mens Health. 2012;9(2):106-112. 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crenshaw KW. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In: Crenshaw K., Gotanda N., Peller G., Thomas K., eds.Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New Press; 1995:359-383. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bowleg L. Towards a critical health equity research stance: why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(5):677-684. 10.1177/1090198117728760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffith DM. “Centering the margins”: moving equity to the center of men’s health research. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(5):1317-1327. 10.1177/1557988318773973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Griffith DM. Achieving men’s health equity. In: Smalley KB., Warren JC., Fernández MI., eds.Health Equity: A Solutions-Focused Approach. Springer Publishing; 2020:197-215. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pieterse AL., Carter RT. An examination of the relationship between general life stress, racism-related stress, and psychological health among Black men. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(1):101-109. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Griffith DM., Johnson JL. Implications of racism for African American men’s cancer risk, morbidity, and mortality. In: Treadwell HM., Xanthos C., Holden KB., eds.Social Determinants of Health Among African-American Men. Jossey-Bass; 2013:21-38. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young AA Jr. The character assassination of Black males: some consequences for research in public health. In: Bogard K., Murry VM., Alexander C., eds.Perspectives on Health Equity and Social Determinants of Health. National Academy of Medicine; 2017:47-62. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weitzer R., Brunson RK. Policing different racial groups in the United States. Cahiers Politiestudies. 2015;6(35):129-145. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller C., Vittrup B. The indirect effects of police racial bias on African American families. J Fam Issues. 2020;41(10):1699-1722. 10.1177/0192513X20929068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2013. NCJ 247282. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justic Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gilbert KL., Ray R. Why police kill Black males with impunity: applying public health critical race praxis (PHCRP) to address the determinants of policing behaviors and “justifiable” homicides in the USA. J Urban Health. 2016;93(1):122-140. 10.1007/s11524-015-0005-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartfield JA., Griffith DM., Bruce MA. Gendered racism is a key to explaining and addressing police-involved shootings of unarmed Black men in America. In: Bruce MA., Hawkins DF., eds.Inequality, Crime, and Health Among African American Males. Emerald Publishing; 2019:155-170. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krieger N. Enough: COVID-19, structural racism, police brutality, plutocracy, climate change—and time for health justice, democratic governance, and an equitable, sustainable future. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1620-1623. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gramlich J. Black imprisonment rate in the U.S. has fallen by a third since 2006. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/share-of-black-white-hispanic-americans-in-prison-2018-vs-2006/

- 74.Nowotny KM., Bailey Z., Brinkley-Rubinstein L. The contribution of prisons and jails to US racial disparities during COVID-19. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(2):197-199. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Macmadu A., Berk J., Kaplowitz E., Mercedes M., Rich JD., Brinkley-Rubinstein L. COVID-19 and mass incarceration: a call for urgent action. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(11):e571-e572. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30231-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Henry BF. Social distancing and incarceration: policy and management strategies to reduce COVID-19 transmission and promote health equity through decarceration. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(4):536-539. 10.1177/1090198120927318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Thorpe RJ Jr. Introduction. In: Griffith DM., Bruce MA., Thorpe RJ Jr., eds.Men’s Health Equity: A Handbook. Routledge/Taylor & Francis; 2019:3-9. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167-194. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):5-8. 10.1177/00333549141291S203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wingfield AH. No More Invisible Man: Race and Gender in Men’s Work. Temple University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams DR. The health of men: structured inequalities and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):724-731. 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson E. The white space. Sociol Race Ethn. 2015;1(1):10-21. 10.1177/2332649214561306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wingfield AH. The modern mammy and the angry Black man: African American professionals’ experiences with gendered racism in the workplace. Race Gend Class. 2007;14(1-2):196-212. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bruce MA., Griffith DM., Thorpe RJ Jr. Social determinants of men’s health disparities. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(4):281-283. 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jack L Jr., Griffith DM. The health of African American men: implications for research and practice. Am J Mens Health. 2013;7(4 suppl):5S-7S. 10.1177/1557988313490190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Heckler M. Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 87.McCord C., Freeman HP. Excess mortality in Harlem. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(3):173-177. 10.1056/NEJM199001183220306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Satcher D., Fryer GE., McCann J., Troutman A., Woolf SH., Rust G. What if we were equal? A comparison of the Black–White mortality gap in 1960 and 2000. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):459-464. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bilal U., Diez-Roux AV. Troubling trends in health disparities. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1557-1558. 10.1056/NEJMc1800328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Griffith DM. Preface: precision medicine approaches to health disparities research. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(suppl 1):129-134. 10.18865/ed.30.S1.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weaver LJ., Kaiser BN. Syndemics theory must take local context seriously: an example of measures for poverty, mental health, and food insecurity. Published online August 20, 2020. Soc Sci Med. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sangaramoorthy T., Benton A. Intersectionality and syndemics: a commentary. Published online February 19, 2021. Soc Sci Med. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tsai AC. Syndemics: a theory in search of data or data in search of a theory? Soc Sci Med. 2018;206:117-122. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lombardo PA., Dorr GM. Eugenics, medical education, and the Public Health Service: another perspective on the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. Bull Hist Med. 2006;80(2):291-316. 10.1353/bhm.2006.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morning A. Ethnic classification in global perspective: a cross-national survey of the 2000 census round. In: Simon P., Piche V., Gagnon AA., eds.Social Statistics and Ethnic Diversity: Cross-National Perspectives in Classifications and Identity Politics. Springer Cham; 2015:17-38. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Summers M. Manhood rights in the age of Jim Crow: evaluating “end-of-men” claims in the context of African American history. Boston Univ Law Rev. 2013;93:745-767. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Summers M. Manliness and Its Discontents: The Black Middle Class and the Transformation of Masculinity, 1900-1930. University of North Carolina Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hine DC., Jenkins E. A question of manhood: a reader in US Black men’s history and masculinity, volume 1. “Manhood Rights”: The Construction of Black Male History and Manhood, 1750-1870. Indiana University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Elder K., Griffith DM. Men’s health: beyond masculinity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1157. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]