Abstract

Premise

The economically important, cosmopolitan soapberry family (Sapindaceae) comprises ca. 1900 species in 144 genera. Since the seminal work of Radlkofer, several authors have attempted to overcome challenges presented by the family’s complex infra‐familial classification. With the advent of molecular systematics, revisions of the various proposed groupings have provided significant momentum, but we still lack a formal classification system rooted in an evolutionary framework.

Methods

Nuclear DNA sequence data were generated for 123 genera (86%) of Sapindaceae using target sequence capture with the Angiosperms353 universal probe set. HybPiper was used to produce aligned DNA matrices. Phylogenetic inferences were obtained using coalescence‐based and concatenated methods. The clades recovered are discussed in light of both benchmark studies to identify synapomorphies and distributional evidence to underpin an updated infra‐familial classification.

Key Results

Coalescence‐based and concatenated phylogenetic trees had identical topologies and node support, except for the placement of Melicoccus bijugatus Jacq. Twenty‐one clades were recovered, which serve as the basis for a revised infra‐familial classification.

Conclusions

Twenty tribes are recognized in four subfamilies: two tribes in Hippocastanoideae, two in Dodonaeoideae, and 16 in Sapindoideae (no tribes are recognized in the monotypic subfamily Xanthoceratoideae). Within Sapindoideae, six new tribes are described: Blomieae Buerki & Callm.; Guindilieae Buerki, Callm. & Acev.‐Rodr.; Haplocoeleae Buerki & Callm.; Stadmanieae Buerki & Callm.; Tristiropsideae Buerki & Callm.; and Ungnadieae Buerki & Callm. This updated classification provides a backbone for further research and conservation efforts on this family.

Keywords: biogeography, infrafamilial classification, new tribes, Sapindaceae, Sapindales, targeted enrichment, taxonomy

The soapberry family (Sapindaceae, Sapindales), comprising ca. 1900 species (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011), has a predominantly pantropical distribution, although some taxa occur in temperate areas (e.g., Acer L.). Biogeographic reconstructions indicate that Sapindaceae originated in Eurasia sometime during the Late Cretaceous, with subsequent dispersals into the southern hemisphere during the Late Paleocene mediated by the Gondwanan break‐up and the emergence of proto‐SE Asia (Buerki et al., 2013). Currently, >80% of the generic diversity is restricted to tropical and subtropical ecosystems of the southern hemisphere, largely resulting from three main routes of dispersal: one that connected Eurasia with Africa associated with the collision of the African and Eurasian plates; a second established between proto‐SE Asia, Africa, and Madagascar, resulting from the break‐up of India and Madagascar and the subsequent northern rafting of India; and a third that connected proto‐SE Asia and Australia, facilitated by the existence of myriad archipelagos in the region (see Buerki et al., 2013 and references therein). Interestingly, South American lineages of Sapindaceae belonging to the Paullinia group (the only one in which lianas have evolved) were shown to have involved the third route of dispersal, via Antarctica, estimated to have occurred during the Middle Eocene (ca. 44 million years ago). The warm climate during this period (with ice probably only occurring in the Antarctic highlands and within and around the Arctic Ocean in the north) combined with the specific tectonic configuration at that time most likely mediated this type of long‐distance dispersal (see Buerki et al., 2013 for more details and de la Estrella et al., 2019 for a review on the role of Antarctica in angiosperm biogeography). Sapindaceae include many economically important species used for their fruits (e.g., guarana [Paullinia cupana Kunth], lychee [Litchi chinensis Sonn.], longan [Dimocarpus longan Lour.], pitomba [Talisia esculenta Radlk.], and rambutan [Nephelium lappaceum L.]), timber (e.g., buckeyes [species of Aesculus L.] and Fijian longan [Pometia pinnata J.R.Forst. & G.Forst.]), or as ornamentals (e.g., Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm. and Ungnadia speciosa Endl.).

Since the seminal work of Radlkofer (1931–1934), several authors have attempted, often with limited success, to develop an improved infra‐familial classification of Sapindaceae (e.g., Klaassen, 1999; Muller and Leenhouts, 1976), which has benefited recently from molecular systematic work that has focused on the family or on particular groups. The phylogenetic study of Harrington et al. (2005), using broad sampling and two plastid markers (matK and rbcL), was the first to provide new insights into relationships within the family. This study placed the monotypic genus Xanthoceras Bunge (long included in Sapindaceae) as sister to a group comprising two clades, one comprising the historically recognized families Aceraceae and Hippocastanaceae, and another containing the remaining genera traditionally assigned to Sapindaceae. Based on these results, Harrington et al. (2005) proposed a broad definition of Sapindaceae in which four subfamilies are recognized, Dodonaeoideae, Hippocastanoideae (including taxa previously assigned to Aceraceae and Hippocastanaceae, along with the genus Handeliodendron Rehder, previously assigned to Dodonaeoideae), Sapindoideae (including the genera Koelreuteria Laxm. and Ungnadia Endl., likewise previously placed in Dodonaeoideae), and Xanthoceratoideae (including just Xanthoceras). Although Harrington et al. (2005) questioned the traditional tribal delimitations proposed by Radlkofer (1931–1934), their sampling was not adequate to propose an alternative.

More recently, Buerki et al. (2009) produced a significantly expanded phylogenetic analysis of the family, increasing both the number of DNA regions used to eight (i.e., one nuclear and seven plastid regions) and the taxonomic sampling (encompassing 85 of the 141 of the genera known at the time, i.e., ca. 60%) in an attempt to test the monophyly and clarify the relationships of the 14 tribes recognized by Radlkofer (1931–1934). Their results revealed a high level of paraphyly and polyphyly at the subfamilial and tribal levels and cast serious doubt on the monophyly of several genera, including Arytera Blume, Cupaniopsis Radlk., and Haplocoelum Radlk. (see below). This prompted Buerki et al. (2009) to propose an informal tribal classification for the 14 clades they recovered in Dodonaeoideae and Sapindoideae as a basis for pursuing a more focused approach using phylogenetic and taxonomic research to identify morphological synapomorphies for each clade, thereby permitting a comprehensive re‐circumscription of the tribes within the family (see also Buerki et al., 2010b, 2012).

Radlkofer (1931–1934) based his infra‐familial classification mainly on the number and type of ovules per locule, fruit morphology, the presence or absence of arils or sarcotestas, leaf type, and cotyledon shape. Subsequent authors questioned the delimitation of certain tribes, although results from molecular analyses have provided support for at least some of them. For instance, in his treatment of Malagasy Sapindaceae, Capuron (1969) showed that several species of the endemic genera Tina Roem. & Schult. and Tinopsis Radlk. exhibited intermediate morphologies between tribes Cupanieae and Schleichereae. Molecular analyses focusing on these and putatively related genera occurring in Madagascar confirmed Capuron’s predictions, leading to the placement of Tina in Cupanieae and its re‐circumscription to include Tinopsis and Neotina Capuron (previously placed in Schleichereae), both of which were nested within Tina (Buerki et al., 2011a). Muller and Leenhouts (1976) expressed doubt about Radlkofer’s use of palynological data to support his classification of the family, especially the monophyly of tribe Melicocceae and the recognition of Cupanieae as distinct from Schleichereae and Nephelieae. Acevedo‐Rodríguez (2003) further challenged the monophyly of Melicocceae based on a morphological cladistic analysis, suggesting that Castanospora F. Muell., Tristira Radlk., and Tristiropsis Radlk. did not belong there. This idea was subsequently confirmed by molecular phylogenetic analyses in which Tristiropsis and Tristira formed distinct lineages from the core of Melicocceae (including Melicoccus P.Browne and Talisia Aubl.) (Harrington et al., 2005; Buerki et al., 2009). The position of Castanospora remains uncertain as it has not been included in any molecular studies to date. Finally, Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2017) applied a phylogenetic approach supported by morphological synapomorphies to investigate Sapindoideae supertribe Paulliniodae (corresponding to tribe Paullinieae of Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011), showing that it comprises four clades, which they recognized as tribes Athyaneae, Bridgesieae, Thouinieae, and Paullinieae. Taken together, the morphological and molecular work published to date points strongly toward the need for an updated infra‐familial classification of Sapindaceae and in particular a new delimitation of tribes.

A total of 141 genera were recognized in the treatment of Sapindaceae by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011), placed in four subfamilies (Dodonaeoideae, Hippocastanoideae, Sapindoideae, and Xanthoceratoideae). However, due to the high level of polyphyly at the infra‐familial level, they only recognized six tribes that included a total of just 44 genera and refrained from placing any of the 97 remaining genera. Moreover, they cast doubt on the taxonomic status and placement of the monotypic African genus Chonopetalum Radlk., listing it as “insufficiently known”. Similarly, they questioned the placement of the monotypic genus Hirania Thulin from Somalia, which Thulin (2007) had hypothesized to be closely related to the Australian genus Diplopeltis Endl. (Dodonaeoideae) based on its flower morphology, but which has an intrastaminal floral disk, a character otherwise known only from the distantly related genus Acer (Hippocastanoideae). These examples further highlight the difficulties of confidently assigning the majority of sapindaceous genera to a tribe.

The problems associated with tribal assignments of genera in Sapindaceae are compounded by uncertainties regarding the delimitation of many genera, including several shown to be polyphyletic. Since the treatment by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011), seven new genera have been described: Alatococcus Acev.‐Rodr. (to accommodate a distinctive species that morphologically resembles Scyphonychium Radlk.; Acevedo‐Rodríguez, 2012), Allophylastrum Acev.‐Rodr. (for a species morphologically similar to Allophylus; Acevedo‐Rodríguez, 2011), Balsas J.Jiménez Ram. & K.Vega (now considered as a synonym of Serjania Mill.; Jiménez Ramírez et al. 2011; see Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2017), and Gereaua Buerki & Callm. (recognized to render Haplocoelum polyphyletic; Buerki et al., 2010a), as well as Lepidocupania Buerki et al. and Neoarytera Callm. et al. (recognized so that the circumscriptions of Arytera and Cupaniopsis, respectively, are now monophyletic; Buerki et al., 2020; see also Buerki et al., 2012). Furthermore, over the last decade several genera have been placed in synonymy, including Neotina and Tinopsis, now included in Tina (Buerki et al., 2011a; Callmander et al., 2011). In all, 144 genera are currently recognized in Sapindaceae, assigned to four subfamilies and eight tribes (see Table 1). While molecular evidence has provided valuable information for refining our understanding of relationships within the family, 36 genera either lack molecular data or have never been assigned to a tribe or to one of the infra‐familial groups defined by Buerki et al. (2009).

TABLE 1.

Table summarizing the infra‐familial classification of Sapindaceae. This table includes previous infra‐familial classifications (Radlkofer, 1931‐1934 and Buerki et al., 2009) as well as the updated classification proposed in this study.

| Clade | Radlkofer (1931–1934) | Buerki et al. (2009, 2011b) | Subfamily (this study) | Tribe (this study) | No. genera | Genera (no. of species) | No. species | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Harpullieae (1) | Xanthoceratoideae (1) | Xanthoceratoideae | NA | 1 | Xanthoceras (1) | 1 | N‐NE China, Korea |

| 2 | Not included (2) | Hippocastanoideae (2) | Hippocastanoideae | Acereae | 2 | Acer (111), Dipteronia (2) | 113 | Northern temperate regions and tropical mountains |

| 3 | Not included (3) | Hippocastanoideae (2), not included (1) | Hippocastanoideae | Hippocastaneae | 3 | Aesculus (13), Billia (2), Handeliodendron (1) | 16 | Europe, North and South America, Asia |

| 4 | Doratoxyleae (6), Harpullieae (1) | Doratoxylon (5), not included (2) | Dodonaeoideae | Doratoxyleae | 7 | Doratoxylon (5), Exothea (3), Filicium (3), Ganophyllum (1), Hippobromus (1), Hypelate (1), Zanha (4) | 18 | North America (Florida), Central America (incl. = West Indies), Africa, Madagascar (incl. Comoro Islands), the Mascarenes, India, and all the way to Australia and the Pacific Islands |

| 5 | Harpullieae (5), Dodonaeeae (4), Cossinieae (2), Cupanieae (2), Doratoxyleae (2), Koelreuterieae (1), Not included (1) | Dodonaea (12), not included (4), Macphersonia (1) | Dodonaeoideae | Dodonaeaeae | 16 | Arfeuillea (1), Averrhoidium (2), Boniodendron (Sinoradlkofera) (2), Conchopetalum (2), Cossinia (4), Diplokeleba (2), Diplopeltis (5), Dodonaea (71), Euchorium (1), Euphorianthus (1), Harpullia (26), Hirania (1), Llagunoa (3), Loxodiscus (1), Magonia (1), Majidea (3) | 126 | Paleotropical |

| 6 | Harpullieae (2) | Delavaya (2) | Sapindoideae | Ungnadieae | 2 | Delavaya (1), Ungnadia (1) | 2 | North America, SW China, N Vietnam |

| 7 | Koelreuterieae (3) | Koelreuteria (2), not included (1) | Sapindoideae | Koelreuterieae | 3 | Erythrophysa (9), Koelreuteria (3), Stocksia (1) | 13 | Africa and Madagascar, South China, Japan, East Iran, Afghanistan |

| 8 | Cupanieae (5), Schleichereae (1) | Not included (3), Schleichera (3) | Sapindoideae | Schleicheraeae | 6 | Amesiodendron (1), Paranephelium (4), Pavieasia (3), Phyllotrichum (1), Schleichera (1), Sisyrolepis (1) | 11 | Southeast Asia |

| 9 | Nephelieae (8), Lepisantheae (5), Cupanieae (4) | Litchi (12), not included (5) | Sapindoideae | Nephelieae | 16 | Aporrhiza (6), Blighia (4), Chytranthus (30), Cubilia (1), Dimocarpus (4), Glenniea (8), Haplocoelopsis (1), Laccodiscus (4), Litchi (1), Nephelium (22), Otonephelium (1), Pancovia (13), Placodiscus (15), Pometia (2), Radlkofera (1), Xerospermum (2) | 116 | Tropical |

| 10 | Sapindeae (6), Cupanieae (2), Lepisantheae (2), Melicocceae (1), Not included (1) | Litchi (7), not included (5) | Sapindoideae | Sapindeae | 12 | Alatococcus (1), Atalaya (12), Deinbollia (40), Eriocoelum (10), Hornea (1), Lepisanthes (24), Pseudima (3), Sapindus (13), Thouinidium (7), Toulicia (14), Tristira (1), Zollingeria (3) | 129 | Tropical |

| 11 | Melicocceae (1) | Tristiropsis (1) | Sapindoideae | Tristiropsidis | 1 | Tristiropsis (3) | 3 | Malesia, Australia, Pacific islands |

| 12 | Cupanieae (1), Schleichereae (1) | Blomia (1), not included (1) | Sapindoideae | Haplocoeleae | 2 | Blighiopsis (2), Haplocoelum (5) | 7 | Tropical Africa |

| 13 | Cupanieae (2), Melicocceae (2) | Melicoccus (3), not included (1) | Sapindoideae | Melicocceae | 4 | Dilodendron (1), Melicoccus (10), Talisia (52), Tripterodendron (1) | 64 | Tropical America |

| 14 | Cupanieae (1) | Blomia (1) | Sapindoideae | Blomieae | 1 | Blomia (1) | 1 | Mexico, Guatemala, Belize |

| 15 | Thouinieae (1) | Paullinia (1) | Sapindoideae | Guindilieae | 1 | Guindilia (3) | 3 | South America |

| 16 | Thouinieae (2) | Paullinia (2) | Sapindoideae | Athyaneae | 2 | Athyana (1), Diatenopteryx (2) | 3 | South America |

| 17 | Thouinieae (1) | Paullinia (1) | Sapindoideae | Bridgesieae | 1 | Bridgesia (1) | 1 | Chile |

| 18 | Not included (1), Paullinieae (1), Thouinieae (1) | Paullinia (2), not included (1) | Sapindoideae | Thouinieae | 3 | Allophylastrum (1), Allophylus (250), Thouinia (28) | 279 | Pantropical |

| 19 | Paullinieae (7) | Paullinia (4), not included (3) | Sapindoideae | Paullinieae | 7 | Cardiospermum (12), Lophostigma (2), Paullinia (200), Serjania (230), Thinouia (9), Urvillea (14) | 467 | Pantropical |

| 20 | Not included (4), Schleichereae (4), Nephelieae (2) | Macphersonia (8), Koelreuteria (1), Not included (1) | Sapindoideae | Stadmanieae | 10 | Beguea (10), Camptolepis (4), Chouxia (6), Gereaua (1), Macphersonia (8), Pappea (1), Plagioscyphus (10), Pseudopteris (3), Stadmania (6), Tsingya (1) | 50 | Madagascar (incl. Comoro Islands), the Mascarenes, Seychelles Islands (Aldabra atoll), tropical Africa |

| 21 | Cupanieae (27), Nephelieae (2), Not included (2), Harpullieae (1), Melicocceae (1), Schleichereae (1) | Cupania (28), Not included (3), Litchi (2), Dodonaea (1) | Sapindoideae | Cupanieae | 34 | Alectryon (30), Arytera (17), Castanospora (1), Cnesmocarpon (4), Cupania (45), Cupaniopsis (43), Dictyoneura (3), Diploglottis (12), Elattostachys (20), Eurycorymbus (1), Gongrodiscus (3), Guioa (65), Jagera (2), Lecaniodiscus (3), Lepiderema (8), Lepidocupania (21), Lepidopetalum (7), Matayba (56), Mischarytera (3), Mischocarpus (15), Molinaea (9), Neoarytera (4), Pentascyphus (1), Podonephelium (9), Rhysotoechia (14), Sarcopteryx (12), Sarcotoechia (11), Scyphonychium (1), Storthocalyx (5), Synima (4), Tina (20), Toechima (7), Trigonachras (8), Vouarana (1) | 463 | Pantropical |

| Un‐placed | Cupanieae (2), Lepisantheae (2), Not included (2), Nephelieae (1), Sapindeae (1) | Not included (7), Koelreuteria (1) | Sapindoideae | Incertae sedis | 9 | Bizonula (1), Chonopetalum (1), Gloeocarpus (1), Gongrospermum (1), Lychnodiscus (7), Namataea (1), Porocystis (2), Pseudopancovia (1), Smelophyllum (1) | 15 | Africa, South America, Phillipines |

In this study, we present the results of a greatly expanded analysis of phylogenetic relationships within Sapindaceae using near‐complete sampling at the genus level and a much larger set of nuclear markers obtained with a targeted enrichment approach based on the universal Angiosperms353 probe set (Johnson et al., 2019). For each of the 21 clades recognized, its taxonomic composition, species richness, biogeography, and key morphological features are discussed. Based on these results, we then present an updated infra‐familial classification of the family in which a total of 20 tribes are recognized (six of which are new) and their constituent genera are listed. As most genera of subfamily Sapindoideae have not previously been assigned to a tribe (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. [2017] accepted the tribes presented by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. [2011]), we base our decisions on the phylogenetic grouping proposed by Buerki et al. (2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2011b).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling

We aimed to sample at least one representative for all genera of Sapindaceae and sought to include collections belonging to type species, although this was not always possible, in which case, we used collections from the DNA and Tissue Collection at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (http://dnabank.science.kew.org/homepage.html) or from our own field‐collected samples. Species representing the type genus of each tribe were also included to support the development of a tribal classification. The resulting sample set included representatives of 123 of the 144 currently recognized genera (86%), 31 of which had never been sequenced before or were not included in any previous family‐wide phylogenetic analyses. All samples are vouchered by collections deposited in one or more of the following herbaria: BM (The Natural History Museum, London, UK), G (Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de Genève, Geneva, Switzerland), K (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK), L (Naturalis, Leiden, Netherlands), MO (Missouri Botanical Garden, St, Louis, MO, USA), and P (Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France) (see Appendix S1 with Supplementary Data and Data Availability section for more details on data repository).

DNA sequencing

DNA extractions were performed with a modified CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987) using 40 mg of leaf material obtained from herbarium specimens or 20 mg of silica‐gel‐dried material. Extracts were subsequently cleaned using magnetic beads following the manufacturer’s protocol (AMPure XP beads; Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Some DNA extracts were obtained from the Kew DNA Bank (see above). The quality and quantity of the DNA extracts were evaluated using a fluorometer (either Qubit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inchinnan, UK; or Quantus, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to obtain 100–200 ng of DNA. The extracts were also run on a 1% agarose gel to determine the size of the fragments. Samples with low concentrations were further assessed using a 4200 TapeStation System with Genomic DNA ScreenTapes (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Before library preparation, samples with an average fragment size exceeding 350 bp were fragmented using a M220 Focused‐Ultrasonicator (with microTUBES AFA Fiber Pre‐Slit Snap‐Cap) from Covaris (Woburn, MA, USA), with shearing times between 30 and 90 s, selected based on the estimated fragment size of a sample to obtain an average fragment size of 350 bp for each sample. Library preparation followed the standard protocol required for dual‐indexed libraries of the DNA NEBNext Ultra II Library Prep Kit and the NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). The quality of the library preparations was assessed using a 4200 TapeStation System with D1000 ScreenTapes, and subsequently quantified on a Quantus fluorometer. The resulting library preparations were pooled (8–24 samples per reaction) and enriched using the Angiosperms353 probe kit (v1; Arbor Biosciences; catalog #308196; Johnson et al., 2019), using the manufacturer’s protocol and a hybridization temperature of 65°C for 24 h. The average fragment size and quality of the pooled samples were assessed again on a 4200 TapeStation System using D1000 ScreenTapes. Library pools were multiplexed for sequencing. Sequencing (2 × 150‐bp paired‐end reads) was either performed on an Illumina MiSeq (with v2, 300 cycles) at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew or on an Illumina HiSeq4000 at Genewiz (Takeley, UK).

Gene recovery and phylogenetic tree reconstructions

Gene‐coding sequences were recovered from each specimen using HybPiper version 1.2 (Johnson et al., 2016) to find matching orthologous sequences from the Angiosperms353 target gene set (Johnson et al., 2019; https://github.com/mossmatters/Angiosperms353). First, specimen read sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2019) with the following parameters: ILLUMINACLIP: <AdapterFastaFile>: 2:30:10:2:true; LEADING: 10; TRAILING: 10; SLIDINGWINDOW: 4:20; and MINLEN: 40. Successfully trimmed read pairs and singletons were then assembled in HybPiper default mode (read mapping to amino acid target sequences with BLASTX) except the ‐‐cov_cutoff parameter was set to 4. The same gene set was also retrieved from a transcriptome for Aesculus pavia L. from the One Thousand Plant (1KP) transcriptome initiative (sample HBHB; Leebens‐Mack et al., 2019). Sequences for the same gene from each sample were aligned with MAFFT version 7.458 (Katoh and Standley, 2013) using the iterative refinement method (option ‐‐maxiterate 1000). Sequences with insufficient coverage (<60%) across well‐occupied columns of each gene alignment were removed. Well‐occupied columns were defined as those with more than 70% of positions occupied by base residues. Sequences with a total length of <85 bases were also removed. The gene trees were built with RAxML‐NG version 0.9.0 (Kozlov et al., 2019) performing an all‐in‐one analysis (option ‐‐all) using a nonparametric bootstrap data set of 100 replicates and the GTR+G model of evolution (option ‐‐model). Two species trees were reconstructed, one using a coalescent‐based method with ASTRAL III (Zhang et al., 2018) and another using a super‐matrix method on a concatenated set of gene alignments with RAxML version 8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014). Before reconstructing the coalescent‐based tree, nodes in the gene trees with bootstrap support values <10% percent were collapsed. For reconstructing the super‐matrix tree, RAxML was set to perform rapid bootstrap analysis (option ‐f a), with the number of alternative runs on distinct starting trees set to 100 (option ‐#) and the GTRGAMMA model of evolution (option ‐m). The ASTRAL and RAxML species trees each contained 135 samples, and the respective local posterior probabilities and bootstrap values were presented at the inner nodes. Both trees were rooted with Xanthoceras sorbifolium Bunge (based on phylogenetic evidence presented in Muellner‐Riehl et al., 2016). The ASTRAL III tree had a final normalized quartet score value of 0.8213.

RESULTS

Sequence recovery and phylogenetic tree reconstructions

For the species sequenced specifically for this study (i.e., excluding Aesculus pavia, which was obtained from OneKP; www.onekp.com), we recovered on average 2,634,488 reads per accession (range: 58,883–11,035,138) of which 451,877 (range: 7853–2,302,320) were on target (16.9%; range 1.14–31.95%). Of the 353 genes targeted by the Angiosperms353 probe set, we retrieved on average 335 (range: 45–349). Both ASTRAL and concatenated analyses were performed on 343 gene alignments. All statistics concerning sequence recovery are presented in Appendix S1 (with data on vouchers and DNA accession numbers).

Angiosperms353 target gene sequences were generated for 123 genera (86%) represented by 135 samples (see Appendix S1 and Data Availability section for details on data repository). Of the 19 currently recognized genera not included in the present study, we attempted to sequence 10, but the samples failed to meet the HybPiper criteria due to the quality of the DNA and its replication (see above) and were therefore not included in further analyses. Material was unavailable for the nine other genera. Of the 19 genera not studied, only eight (viz. Bizonula Pellegr., Chonopetalum Radlk., Gloeocarpus Radlk., Gongrospermum Radlk., Lychnodiscus Radlk., Namataea D.W.Thomas & D.J.Harris, Porocystis Radlk., and Pseudopancovia Pellegr., representing just 15 species) entirely lacked genomic or phylogenetic information, prompting us to abstain from formally assigning them to a tribe in the infra‐familial classification presented below. For the 11 remaining genera, although not formally represented in our analyses, there is sufficient information available from previous phylogenetic studies to permit their assignment to a tribe. This approach is further justified given that we have attempted to include a representative of the type genus for each previously recognized tribe (as defined by Radlkofer [1931–1934] and Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. [2011, 2017]). These genera and their suggested group placements, as indicated in previous phylogenetic studies, are as follows: Averrhoidium Baill. (Dodonaea group; Buerki et al., 2009), Cardiospermum L. (Paullinia group; Buerki et al., 2009; Chery et al., 2019), Chouxia Capuron (Macphersonia group; Buerki et al., 2010a), Chytranthus Hook. f. (Litchi group; Buerki et al., 2009), Cossinia Comm. ex Lam. (Dodonaea group; Buerki et al., 2012), Diplokeleba N.E.Brown (Dodonaea group; Buerki et al., 2011b), Doratoxylon Thouars ex Hook. f. (Doratoxylon group; Buerki et al., 2009), Erythrophysa E.Mey ex Arnott (Koelreuteria group; Buerki et al., 2011b), Schleichera Willd. (Schleichera group; Buerki et al., 2009), Scyphonychium (Cupania group; Buerki et al., 2011b), and Smelophyllum Radlk. (Koelreuteria group; Buerki et al., 2011b). We were unable to include DNA sequences of these latter genera in the analyses presented here since they were represented only by plastid or nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences (rather than nuclear genes, targeted by the Angiosperms353 baiting kit; see above).

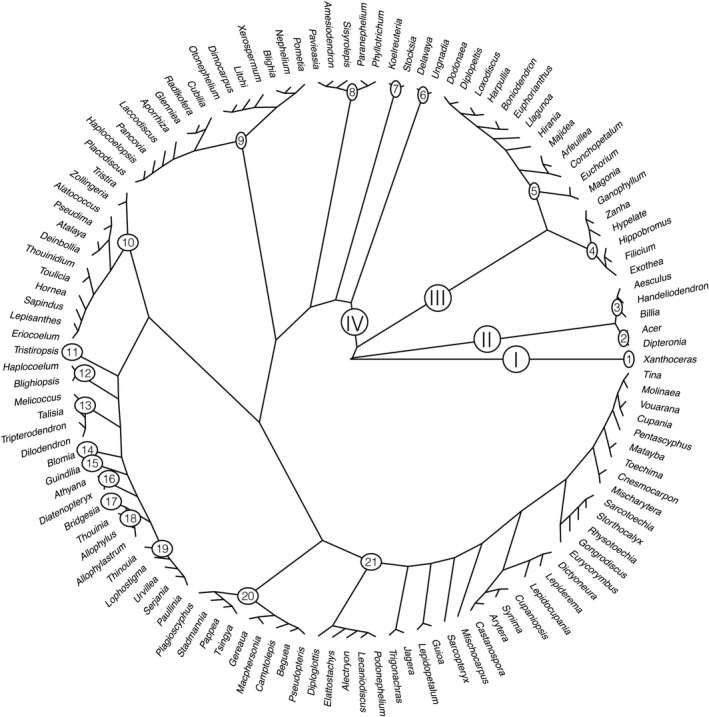

RAxML and ASTRAL phylogenetic trees are available in Appendices S2 and S3 (newick trees are available here: https://github.com/svenbuerki/Angio353_Sapindaceae/tree/master/Phylogenetic_trees). The phylogenetic trees obtained from the ASTRAL III coalescent‐based analysis and the RAxML concatenated maximum likelihood analysis are identical in terms of phylogenetic clustering/topologies and node support, except for the placement of Melicoccus bijugatus Jacq., which appears on its own in the ASTRAL phylogenetic tree, whereas it is inferred as sister to representatives of Talisia, Tripterodendron Radlk., and Dilodendron Radlk. in the RAxML phylogenetic tree (see clade 20 in Appendices S2, S3). Hereafter, we will only refer to the RAxML phylogenetic tree because it best supports previous phylogenetic hypotheses concerning the position of Melicoccus as sister to Talisia, Tripterodendon, and Dilodendron (e.g., Buerki et al., 2009, 2011b). A simplified, genus‐level RAxML phylogenetic tree of Sapindaceae is presented in Fig. 1. Overall, 21 highly supported clades are identified, which serve as the basis for the new tribal classification presented below. Among these 21 clades, four are represented by a single genus: clades 1 (Xanthoceras), 11 (Tristiropsis), 14 (Blomia Miranda), and 15 (Guindilia Gillies ex Hook. & Arn.).

FIGURE 1.

Simplified RAxML genus‐level Sapindaceae phylogeny based on nuclear Angiosperms353 target gene sequences. Clades (Arabic numbers corresponds to tribes and Roman numbers to subfamilies) are displayed as well as bootstrap support values. See Appendix S1 for more details on species sampling and node support.

Table 1 summarizes the phylogenetic groups inferred in this study and compares them to those obtained by Buerki et al. (2009, 2011b) and to the tribes recognized by Radlkofer (1931‐1934). The table also includes data on the number of genera, species richness, and overall distribution of each clade. Moreover, it lists the nine genera for which no genomic data and/or phylogenetic hypotheses are available.

DISCUSSION

Overview of clades: evidence for a revised phylogenetic classification of Sapindaceae

Although there were minor differences in the topologies of the ASTRAL and RAxML phylogenetic trees (see Fig. 1 and Appendices S2, S3), they both overwhelmingly support the four subfamilies delimited by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011). Furthermore, the information provided by our analyses strongly supports the recognition of 20 tribes, each corresponding to one of the well‐supported clades we have recovered within Sapindaceae (clade 1 corresponds to Xanthoceras, the only genus in subfamily Xanthoceratoideae, within which we have refrained from formally recognizing a tribe; see below and Fig. 1; Table 1). Unlike in previous molecular studies (e.g., Buerki et al., 2009; Harrington et al., 2005), the analyses presented here, which include the most complete generic coverage to date for the family (123 of 144 currently recognized genera; 86%), fully resolve the relationships between these clades (especially within the largest subfamily, Sapindoideae). Moreover, given the high level of agreement between the clades we have recovered and those reported in previous studies (e.g., Buerki et al., 2009, 2011b; Muellner‐Riehl et al., 2016), we are able to deduce the phylogenetic position of 10 genera whose placement has been particularly difficult. The placement of just nine genera, for which no sequence data are available, remains uncertain (Table 1).

Although the phylogenetic relationships among genera of Sapindaceae presented here are highly congruent with those reported in previous studies, they differ by the recovery of two groups for which limited support was previously available, i.e., the Litchi and Blomia groups (see below for more details; Fig. 1). A better understanding of the evolution and circumscription of genera within the Litchi group is especially important since it contains some of the most economically important crop species of Sapindaceae (in particular lychee, rambutan, and longan). These species are all placed in clade 9 (see below), an explicit phylogenetic hypothesis that opens up opportunities for identifying wild relatives of crops and developing long‐term conservation programs that target these important taxa (see Aubriot et al., 2018 for an example regarding eggplant). Overall, the hypotheses embodied in our new infra‐familial classification will not only contribute to a more robust taxonomy of Sapindaceae, but will also provide a much‐improved framework for inferring the evolution and biogeography of this cosmopolitan family compared to earlier studies (e.g., Buerki et al., 2011c, Buerki et al., 2013).

The 21 clades retrieved in the present study are presented below by subfamily, following the phylogenetic sequence depicted in Fig. 1 (see Appendices S1, S2 for more details on species sampled). Morphological synapomorphies for the subfamilies follow Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011). Our current understanding of each clade is reviewed, including species richness, distribution, and morphology, along with a discussion of the implications of this revised infra‐familial classification (especially focusing on tribal circumscriptions). Genera not represented in our phylogenetic analyses but that were included in previous studies are also discussed.

I. Subfamily Xanthoceratoideae

Clade 1

This clade contains only the monotypic, temperate, Chinese and Korean genus Xanthoceras (Fig. 2A), the sole member of subfamily Xanthoceratoideae, which can be differentiated from taxa belonging to the other subfamilies of Sapindaceae by its large flowers (petals ca. 2 cm long) and disc with 5 horn‐like appendages, the presence of 7 or 8 ovules per locule (all fertile), more than 15 seeds per fruit, and alternate, deciduous, imparipinnate leaves (Buerki et al., 2010b). Based on its phylogenetic position and unique spatiotemporal history, together with these clear morphological synapomorphies, Buerki et al. (2010b, 2011c) described the family Xanthocerataceae and recognized Aceraceae and Hippocastanaceae as distinct from a more narrowly delimited Sapindaceae nearly identical in circumscription to that used for nearly a century and a half. However, while there is strong justification for these familial delimitations (see Buerki et al., 2010b) and the decision to recognize one or four families is a matter of preference, the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV, 2016) adopted a single, broadly defined family, and the classification presented here is aligned with their interpretation.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Xanthoceras sorbifolia, cultivated at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK. (B) Acer campbellii var. serratifolium, China (Boufford 43672). (C) Aesculus indica cultivated at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK. (D) Doratoxylon chouxii, Madagascar (Rakotovao et al. 6303). (E) Nephelium cuspidatum, Malaysia (Borneo) (Buerki et al. 359). (F) Dodonaea madagascariensis, Madagascar (Lowry 6285). (G) Paranephelium joannis, Malaysia (Borneo) (Buerki et al. 358). (H) Erythrophysa aesculina, Madagascar (Phillipson 5704). Photo credits: © F. Forest (A, C), © C. Davidson (B, E), © C. Rakotovao (D), © P. B. Phillipson (F, H), and © M. W. Callmander (G).

II. Subfamily Hippocastanoideae

This subfamily comprises five genera and ca. 130 species, primarily found in northern temperate ecosystems, with some lineages that have colonized tropical South America. Hippocastanoideae are characterized by opposite leaves and the presence of two ovules per locule (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011). Our phylogenetic analyses confirm that the subfamily comprises two clades, recognized as Aceraceae and Hippocastanaceae by Buerki et al. (2010b) but treated below as tribes within Sapindaceae.

Clade 2

This clade contains two genera, Acer L. (111 species in northern temperate and tropical Asian mountains, Fig. 2B) and Dipteronia Oliver (2 species in China), characterized by their actinomorphic flowers, petals without appendages, and an annular disk (Buerki et al., 2010b).

Clade 3

This clade includes three genera, Aesculus (13 species in Europe, North America, and Asia, Fig. 2C), Billia Peyr. (2 species from southern Mexico to tropical America), and Handeliodendron (1 species in deciduous forests of China). Its members are characterized by zygomorphic flowers, petals usually with appendages, and a unilateral disk (Buerki et al., 2010b).

III. Subfamily Dodonaeoideae

This subfamily comprises 24 genera and ca. 140 species, characterized by alternate leaves and petals that usually lack appendages (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011). Our phylogenetic analyses placed these genera in two clades that are consistent with the corresponding tribes recognized by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011).

Clade 4

This clade contains seven genera and 18 species and is distributed across the southern United States (Florida), Central America (including the West Indies), Africa, Madagascar (including the Mascarene islands), and India, extending all the way to Australia and the Pacific Islands (Table 1). Clade 4 was previously identified by Buerki et al. (2009), who referred to it as the Doratoxylon group, to which only five genera were assigned, Doratoxylon (Fig. 2D), Filicium Thwaites ex Hook.f., Ganophyllum Blume, Hippobromus Ecklon & Zeyher, and Hypelate P.E.Browne. In the present study, this same clade was recovered, also including Exothea Macfad. (1 species in Florida, the West Indies, and Central America to northwestern South America) and Zanha Hiern (4 species in tropical Africa and Madagascar), for a total of seven genera, very much like Radlkofer’s tribe Doratoxyleae, with the exception that we have placed Euchorium Eckman & Radlk. in clade 5 (see below).

Clade 5

This clade contains 16 genera with >120 species and is distributed across the Paleotropics. Eleven of these genera were previously assigned to the Dodonaea group by Buerki et al. (2009, 2011b, 2012) and were included by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011) in Dodonaeae: viz. Arfeuillea Pierre ex Radlk. (1 species in Southeast Asia), Cossinia (4 species, disjunct between the Mascarenes islands and Australia and the Pacific islands), Diplokeleba (2 species in South America), Diplopeltis (5 species in Australia), Dodonaea Miller (65 species distributed across the paleotropics, Fig. 2F), Euphorianthus Radlk. (1 species in Malesia), Harpullia Roxb. (26 species in Asia, Malesia, Australia, and the Pacific islands), Llagunoa Ruíz & Pavón (3 species in tropical South America), Loxodiscus Hook.f. (1 species in New Caledonia), Magonia A.St.‐Hil. (1 species in South America), and Majidea J.Kirk ex Oliv. (3 species in tropical Africa and Madagascar). Unfortunately, we were not able to include representatives of Cossinia and Diplokeleba in our phylogenetic analyses, although they were placed in this clade by Buerki et al. (2012). In this study, we present new genomic and phylogenetic data for three additional genera that belong to clade 5: Euchorium (1 species in Cuba), Hirania (1 species in Somalia), and Sinoradlkofera F.G.Mey. (1 species in China). Euchorium and Hirania are only known by their type specimens, which were sampled for our study. Euchorium was previously placed in Doratoxyleae by Radlkofer (1931–1934) and by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011), but its tribal placement remained uncertain due to the lack of data on fruit morphology. Our phylogenetic analyses support its placement in clade 5, close to Magonia (Fig. 1). Our results are also consistent with the morphological observations made by Thulin (2007), which prompted him to describe Hirania as a new genus and to place it in Dodonaeoideae based on its zygomorphic flowers (with five sepals with gland‐tipped trichomes along margins, and four pink, subequal, clawed petals without appendages) and eight glabrous stamens. Thulin (2007) hypothesized that Hirania was closely related to Diplopeltis, an interpretation that was not supported by our analyses (Fig. 1). Finally, the sole species of Sinoradlkofera was previously included in Koelreuteria (a member of Sapindoideae) by Radlkofer (1931–1934), but further morphological analyses will be needed to confirm its tribal placement. Finally, genomic data presented here for the Malagasy genus Conchopetalum Radlk. strongly support its placement in Dodonaeaeae (Table 1; Fig. 1), as previously suggested by Capuron (1969) based on overall morphology, whereas the results of Buerki et al. (2009) had placed it in the Macphersonia group.

IV. Subfamily Sapindoideae

This subfamily comprises 107 genera and ca. 1400 species and is characterized by alternate leaves, petal appendages usually present, and an annular or unilateral disk (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011). Our phylogenetic analyses recovered 16 clades within Sapindoideae, which are used below to delimit the corresponding tribes in our new infra‐familial classification. Because the taxa included in these clades have either one or two ovules per carpel, we consider this to represent a synapomorphy for Sapindoideae.

Clade 6

This clade exhibits a disjunct distribution between southern North America (Ungnadia, 1 species) and southwestern China and northern Vietnam (Delavaya Franch., 1 species; Fig. 3A). It is sister to the remainder of Sapindoideae, a relationship found previously by Buerki et al. (2011b). Its members are characterized by two ovules per carpel, type‐A (colporate spheroidal) pollen, elongated basal petal appendages, glabrous stamens, and Cupanieae wood anatomy (Buerki et al., 2009; Klaassen, 1999).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Delavaya toxocarpa, China (Boufford 44087). (B) Lepisanthes rubiginosa, Thailand (Callmander et al. 1167). (C) Tristiropsis obtusangula, Guam. (D) Haplocoelum intermedium, Gabon (Nguema 732). (E) Blomia pisca, Mexico (Acevedo‐Rodríguez 12242). (F) Guindilia trinervis, Chile. Photo credits: © C. Davidson (A), © P. Chassot (B), © G. C. Fiedler (C), © D. Nguema (D), © P. Acevedo‐Rodríguez (E), and © M. Belov (F).

Clade 7

This clade contains three genera and 13 species, assigned by Radlkofer to Koelreuterieae, and exhibits a disjunct distribution between Africa‐Madagascar and southern China, Japan, eastern Iran, and Afghanistan (Table 1). We provide new genomic and phylogenetic data for Stocksia Benth., a monotypic genus restricted to eastern Iran and Afghanistan, which is sister to Koelreuteria (3 species) from southern China and Japan (Fig. 1). This placement is consistent with Radlkofer’s classification based on morphological similarities. The third genus in clade 7, the African‐Malagasy Erythrophysa (9 species; Fig. 2H), was not included in our study, but previous phylogenetic inferences strongly support its inclusion (Buerki et al., 2011b). Buerki et al. (2011b) recovered Erythrophysa as sister to a clade comprising Koelreuteria and the South African monotypic genus Smelophyllum. We have therefore adopted their assessment, retaining these three genera in Koelreuterieae, with the caveat that additional genetic data will be necessary to confirm the placement of Smelophyllum. Members of clade 7 are characterized by zygomorphic flowers, 3‐locular inflated capsules, and seeds without an aril or sarcotesta.

Clade 8

This clade contains six genera and 11 species distributed across Southeast Asia (Table 1). While we were not able to include representatives of the monotypic genus Schleichera in our study, clade 8 corresponds to the Schleichera group as defined by Buerki et al. (2009), with the addition of Pavieasia Pierre (3 species in southern China and northern Vietnam), Phyllotrichum Thorel ex Lecomte (1 species in Laos), and Sisyrolepis Radlk. (1 species in Thailand and Cambodia), for which no genomic data were previously available (Fig. 1). These three genera were assigned to Cupanieae by Radlkofer (Table 1), a tribe that has been shown to be highly polyphyletic (e.g., Buerki et al., 2009, 2011a,b, 2012). The circumscription of Schleicheraeae, as defined by Radlkofer (1931–1934) and treated by Capuron (1969), includes 12 genera and exhibits a disjunct distribution between Africa‐Madagascar and Southeast Asia (Buerki et al., 2009). The delimitation of clade 8 presented here is more biogeographically coherent than Schleicheraeae as it only contains genera occurring in Asia (Table 1). Although there is strong molecular support for this clade, further examination of morphological characters will be required to identify synapomorphies that support this circumscription. It is worth noting that the poorly known genera Phyllotrichum and Sisyrolepis have zygomorphic flowers (vs. actinomorphic flowers in the other genera) and similar overall morphologies. Based on these characters, we hypothesize that they could represent a single genus, although our phylogenetic analyses do not support this and suggest instead that they belong to two distinct subclades (Fig. 1).

Clade 9

This clade includes 16 genera and 116 species, distributed across the tropics. It contains most of the economically important crop species found in Sapindaceae (belonging to Dimocarpus Lour, Litchi Sonn., and Nephelium L.; Table 1). Clade 9 includes most of the genera of the Litchi group, as defined by Buerki et al. (2009, 2011b), along with 12 additional genera (including the type genus of Nephelieae): Blighia Koenig (4 species in tropical Africa), Chytranthus Hook. f. (30 species in Africa), Cubilia Blume (1 species in Malesia), Dimocarpus (4 species in Southeast Asia and Australia), Glenniea Hook. f. (8 species in tropical Africa, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and Malesia), Haplocoelopsis F.G.Davies (1 species in East Africa), Laccodiscus Radlk. (4 species in West Africa), Litchi (1 species in tropical China to West Malesia), Nephelium (22 species in Southeast Asia and Malesia; Fig. 2E), Pancovia Willd. (13 species in tropical Africa), Pometia J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. (2 species in Malesia and the Pacific islands), and Xerospermum Blume (2 species in Indochinese Peninsula and Malesia). These genera were previously dispersed among tribes Nephelieae, Lepisantheae, and Cupanieae, distinguished from one another by Radlkofer (1931–1934) based on the presence of a fleshy aril in the first tribe and its absence in the second, and of a dry or fleshy aril in the third tribe. The presence of these morphological features among the members of clade 9 supports the hypothesis of convergent evolution of seed morphology, which is most likely connected to shifts in dispersal mechanisms (as discussed by Buerki et al., 2011a). In addition, four genera for which no genomic data were available before the present study belong to this clade: Aporrhiza Radlk. (6 species in tropical Africa), Otonephelium Radlk. (1 species in India), Placodiscus Radlk. (15 species in tropical West Africa), and Radlkofera Gilg. (1 species in tropical Africa) (Fig. 1). Otonephelium was assigned to Nephelieae, whereas Aporrhiza was placed in Cupanieae, and Placodiscus and Radlkofera were included in Lepisantheae (Radlkofer, 1931–1934). We have not yet identified any morphological synapomorphies that define this clade, but suspect that floral features may be useful for its characterization.

Clade 10

This clade includes 12 genera and ca. 130 species, distributed across the tropics (Table 1). Seven of these genera were placed by Buerki et al. (2009) in their Litchi group: Atalaya Blume (12 species in South Africa, Australia, and New Guinea), Deinbollia Schumach. & Thonn. (40 species in tropical Africa and Madagascar), Eriocoelum Hook. f. (10 species in tropical Africa), Lepisanthes Blume (the type genus of Lepisantheae, including 24 species in tropical Africa, Madagascar, Southeast Asia, Malesia, and Northwest Australia; Fig. 3B), Pseudima Radlk. (3 species in South America), Sapindus L. (the type of Sapindaea, including 13 species widely distributed across the tropics), and Tristira (1 species in Malesia). The current study provides strong support for their inclusion in clade 10. The rest of the genera belonging to clade 10 were sequenced for the first time as part of our study: Alatococcus (1 species in Southeast Brazil), Hornea Baker (1 species in Mauritius), Toulicia Aublet. (14 species in tropical America), Thouinidium Radlk. (7 species in Mexico and the West Indies), and Zollingeria Kurz. (3 species in Southeast Asia and Malesia) (see Table 1). Overall, six of the seven genera assigned to Sapindeae by Radlkofer (the seventh, the tropical South American Porocystis, was not sampled and lacks any genomic data) were inferred to belong to clade 10. The remaining genera in this clade were previously placed in three other tribes, viz. Cupanieae (Eriocoelum and Pseudima), Lepisantheae (Lepisanthes and Zollingeria), and Melicocceae (Tristira), to which the recently described Brazilian monotypic genus Alatococcus was subsequently added (Acevedo‐Rodríguez, 2012). According to Radlkofer (1931–1934), Sapindeae are morphologically very similar to Lepisantheae in having a single ovule per carpel and indehiscent fruits, and in lacking an aril. The placement of Alatococcus, Lepisanthes, Tristira, and Zollingeria in clade 10 is supported by the presence of a single ovule per carpel and indehiscent fruits, and the absence of an arillode (Adema et al., 1994; Acevedo‐Rodríguez, 2012). Ericoelum and Pseudima differ from the remaining genera in this clade by their dehiscent fruits and dry arils. However, despite sharing these characters, these two genera are not closely related to one another, which suggests that dehiscent fruits with dry arils may have evolved twice within the clade (Fig. 1).

Clade 11

This clade includes a single genus, Tristiropsis, with three species that occur in Malesia, Australia, and the Pacific islands (Fig. 3C, Table 1). Tristiropsis was assigned to Melicocceae by Radlkofer (1931–1934) but excluded from the tribe by Acevedo‐Rodríguez (2003) due to its distinct fruit type, which is not shared with its other members. Our analyses confirm its exclusion from Melicocceae, and due to its distinctive fruits, which are unique within Sapindaceae (drupes with a [2]3‐locular stony endocarps), we have opted to place Tristiropsis in its own tribe (see below).

Clade 12

This clade includes two genera (Haplocoelum and Blighiopsis Van der Veken) with seven species occurring in tropical Africa. Two species of Haplocoelum (including the type, H. inopleum Radlk.; Fig. 3D) were placed by Buerki et al. (2009, 2010a) along with Blomia in their Blomia group, although with poor support. The present analyses, for which Blighiopsis was sequenced for the first time, recover Blomia as a separate clade from Haplocoelum and Blighiopsis. The latter two genera are morphologically similar, as reflected in the recent transfer of Haplocoelum gabonicum Breteler to Blighiopsis by Hopkins (2013). They share the absence of partition walls in the fruit, resulting in a unilocular capsule (Fouilly and Hallé, 1973). In recognition of the distinctiveness of this clade, we describe a new tribe to accommodate its members (see below).

Clade 13

This clade includes four genera and >60 species occurring in tropical America. Three of the four genera were assigned by Buerki et al. (2009, 2011b) to their Melicoccus group: Dilodendron (1 species in South America), Melicoccus (10 species in tropical America), and Talisia (52 species in tropical America; Fig. 4B). We show here that the monotypic Brazilian genus Tripterodendron (sequenced for the first time) also belongs to this clade, within which it is sister to Dilodendron. Both of these genera were placed in Cupanieae by Radlkofer (1931–1934), and they share similar morphologies (see Gentry and Steyermark, 1987). Acevedo‐Rodríguez (2003) published a monograph of Talisia and Melicoccus, which are characterized by indehiscent fruits and sarcotestal seeds. This treatment could provide a basis for identifying morphological similarities between these genera and the species of Dilodendron and Tripterodendron, but despite the very coherent biogeography they exhibit, it remains unclear whether any morphological characters represent synapomorphies for the clade.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Bridgesia incisifolia, Chile (B) Talisia sp., Peru (Farfan et al. 771). (C) Athyana weinmanniifolia, Bolivia (Arroyo et al. 5625). (D) Thouinia brachybotrya, Nicaragua (Stevens & Montiel 28469). (E) Cardiospermum grandiflorum, Paraguay (Stevens et al. 31269). (F) Stadmania glauca, Madagascar (Schatz 3854). (G) Podonephelium pachycaule, New Caledonia (Munzinger et al. 5935). Photo credits: © C. De Schrevel (A), © C. Davidson (B, E), © G. A. Parada (C), © O. M. Montiel (D), and © P. P. Lowry II (F, G).

Clade 14

This clade only includes the monotypic genus Blomia (Fig. 3E), which occurs in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. As discussed above (see clade 12), this genus was previously found to be sister to the African Haplocoelum, but the analyses presented here support its evolutionary distinctiveness, which has led us to describe a new tribe to accommodate it (see below).

Clade 15

This clade only includes the South American genus Guindilia (3 species; Fig. 3F), which was excluded from Paullinieae by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2017) and inferred to be sister to supertribe Paulliniodae (Appendix S3). Morphologically, Guindilia differs from members of Paulliniodae by the presence of opposite, simple leaves (vs. alternate, compound leaves) (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2017). Although the floral disc in Guindilia has been shown to be unilateral, it is roughly pyramidal in shape and two‐lobed, a feature that is not present in Paulliniodae (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2017). Urdampilleta et al. (2016) informally recognized the Guindilia group based on palynological, karyological, and molecular phylogenetic data. To recognize the morphological and evolutionary distinctiveness of Guindilia, we have placed it in a new tribe, described below.

Clades 16–19

These clades correspond to supertribe Paulliniodae, as defined by Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2017). This group is characterized morphologically by zygomorphic flowers, thyrses with lateral cincinni, corollas of four petals, and alternate leaves with a well‐developed distal leaflet. Our study recovered the same phylogenetic clustering as Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2017), and we have therefore adopted the tribal delimitations presented in their study. Paulliniodae thus contain four clades, recognized as tribes Athyaneae (clade 16), Bridgesieae (clade 17), Thouinieae (clade 18), and Paullinieae (clade 19). Athyaneae comprise Athyana (Griseb.) Radlk. (1 species in South America; Fig. 4C) and Diatenopteryx Radlk. (2 species in South America), and contain trees with exstipulate pinnately compound leaves and isopolar, spherical, colporate pollen grains. Bridgesieae contain the monotypic Chilean shrub genus Bridgesia Bertero ex Cambess., which has exstipulate, simple leaves and isopolar, spherical, tricolporate pollen grains. Thouinieae comprise three genera of trees or shrubs with exstipulate, trifoliolate or unifoliolate leaves: Allophylastrum (1 species in Brazil and Guyana), Allophylus L. (250 species across the tropics), and Thouinia Poit. (28 species in Mexico and the West Indies; Fig. 4D). Paullinieae are circumscribed to include six genera: Cardiospermum (6 or 7 species in tropical America, 1 species also native to Africa; Fig. 4E), Lophostigma Radlk. (2 species in South America), Paullinia L. (200 species in tropical America, 1 species also in Africa and Madagascar), Serjania (230 species in tropical America), Thinouia Planch. & Triana (14 species in tropical America), and Urvillea Kunth (21 species in tropical America). They are climbers or climber‐derived shrubs with stipulate leaves and a pair of inflorescence tendrils. We were not able to include representatives of Cardiospermum in our analyses, but previous studies have confirmed its placement in Paullinieae (e.g., Buerki et al., 2009; Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2017; Chery et al., 2019).

Clade 20

This clade comprises 10 genera and >50 species occurring in Madagascar (including the Comoro islands), the Mascarene islands, the Seychelles islands (Aldabra atoll), and tropical Africa. It corresponds to the Macphersonia group of Buerki et al. (2009, 2010a, 2014), with the addition of the East African and Malagasy genus Camptolepis Radlk. (4 species) and the African‐Malagasy Stadmania Lam. ex Poir. (6 species; Fig. 3F) (see Table 1 for a list of all genera). The first of these genera was not sequenced before the present study, although Capuron (1969) included it among Malagasy Schleichereae, along with the rest of the genera belonging to clade 20, based on its morphology, whereas Stadmania was assigned to Nephelieae (Radlkofer, 1931–1934) and was previously recovered in the Koelreuteria group (see Buerki et al., 2011b), although its position there was not conclusive due to missing data. The placement of Stadmania in clade 20 is strongly supported not only by the results of our phylogenetic analyses, but also by its actinomorphic flowers (absent in S. oppositifolia Lam. ex Poir.), petals (when present) with basal appendage(s), a 3‐carpelate ovary with a single ovule per carpel, and an indehiscent fruit with a seed covered by a fleshy, translucid aril, a suite of character shared with all the other genera in clade 20 (Capuron, 1969). In recognition of the coherence of this clade, we describe a new tribe to accommodate its members (see below).

Clade 21

This clade, which corresponds to the Cupania group of Buerki et al. (2009, 2012, 2013, 2020), is the most diverse lineage in Sapindaceae at the generic level, with 34 genera and >460 species occurring throughout the tropics. Buerki et al. (2013) hypothesized that the high level of species richness exhibited by this clade resulted from interactions between climate change at the Eocene‐Oligocene boundary and the emergence of islands in Southeast Asia, triggering rapid biogeographic movements promoting its diversification. This interpretation was also supported by relatively short branch lengths within this clade when compared to the rest of Sapindoideae, which resulted in phylogenetic uncertainty in several lineages (for further details, see Buerki et al., 2012, 2013). Although a few nodes in clade 21 have low support in the analyses presented in this study, the information provided by the Angiosperms353 baiting kit enabled the resolution of relationships among its members, especially the early‐diverging lineages (Fig. 1). Based on our results, four genera for which no genomic data were previously available have been added to the Cupania group: Castanospora F.Muell. (1 species in Northeast Australia), Cnesmocarpon Adema (4 species in Australia and Papua New Guinea), Pentascyphus Radlk. (1 species in Guyana), and Trigonachras Radlk. (8 species in Malesia). The last three of these genera were placed in Cupanieae by Radlkofer (1931–1934), and their morphologies align with those of the other genera currently recognized as part of this clade. Castanospora was tentatively assigned to Melicocceae, but Acevedo‐Rodríguez (2003) rejected this hypothesis based on wood anatomy (Klaassen, 1999). At this stage, further investigation of the morphology of Castanospora will be required before any conclusion can be reached regarding its position within clade 21. However, it is generally assumed to be phylogenetically close to genera occurring in Australia, Malesia, and the Pacific islands (Fig. 1; Table 1). Finally, our new molecular data indicate that Lecaniodiscus Planch. ex Benth. (3 species in tropical Africa) and Lepidopetalum Blume (7 species in India, Australia and the Solomon Islands), previously included in the Litchi group (Buerki et al., 2009), likewise belong to this clade. Lepidopetalum was placed in Cupanieae by Radlkofer (1931–1934), sharing a morphology and distribution similar to those of the other genera in this group, whereas Lecaniodiscus was assigned to Schleichereae based on its fruit morphology (Radlkofer, 1931–1934). Buerki et al. (2011a) studied generic circumscriptions among Malagasy‐centered genera from this clade and showed that fruit morphology can switch very rapidly, most likely associated to shifts in dispersal mechanisms. Given this situation, we do not exclude the possibility that Lecaniodiscus could belong to this clade. Finally, it is worth noting that Lecaniodiscus is the only genus in clade 21 to occur in continental Africa, extending its range, which previously had a disjunct distribution between the Neotropics and Paleotropics (Buerki et al., 2011c, 2013). A full list of the 34 genera belonging to this clade is presented in Table 1.

Unplaced genera

We have not been able to provide phylogenetic information in the present study for nine genera representing 16 species (Table 1). Smellophylum was discussed above (see clade 7). Bizonula (1 species in Gabon) was placed in Schleichereae by Radlkofer (1931–1934) to accommodate its morphological affinities with the Malagasy genus Macphersonia Blume (see Pellegrin, 1924; Fouilly and Hallé, 1973). Our phylogenetic analyses have demonstrated that Macphersonia is not a member of Schleichereae (sensu Radlkofer) but rather belongs to clade 20. We therefore hypothesize that Bizonula probably belongs to the clade 20, although this would have to be confirmed by molecular analyses. Gloeocarpus and Gongrospermum, monotypic genera endemic to the Philippines, were included in Cupanieae by Radlkofer (1931–1934), and their fruit morphologies are indeed very close to Cupaniopsis, which would support their placement in clade 21. The tropical West African Lychnodiscus (6 species) was also previously placed in Cupanieae by Radlkofer (1931–1934), and most of the genera he assigned to this tribe were recovered in clade 21, but apart from Lecaniodiscus, none occur in mainland Africa. A matK sequence (GenBank accession MN370324) of L. dananensis Aubrév. & Pellegr. was produced by Janssens et al. (2020) for DNA barcoding analyses. A BLAST analysis on this sequence suggested a close relationship with species of the African genus Chytranthus, which would instead place Lychnodiscus in clade 9. Namataea (1 species in Cameroon) was regarded as a member of Lepisantheae by Thomas and Harris (1999) because it morphologically resembles Chytranthus, prompting us to hypothesize that it may also belong to clade 9. Pseudopancovia (1 species in tropical West Africa) was also included in Lepisantheae (Radlkofer, 1931–1934), and its flower and fruit morphologies would also suggest a close relationship with genera in clade 9. Porocystis (2 species), distributed in South America, was placed in Sapindeae by Radlkofer (1931–1934). A matK sequence of P. toulicioides Radlk. was produced by Clark, Pennington and Dexter (GenBank accession MH024824) but has to be taken with caution since it is not associated with a publication or a cited voucher (at least not as of 1 June 2021). A BLAST analysis revealed that this species is genetically closely related to species of Alectryon Gaertn. and Mischarytera (Radlk.) H.Turner, which would suggest that Porocystis may belong to clade 21. Finally, we are unable to comment on the affinities of the monotypic African Chonopetalum, since it is only known from the type specimen and is in critical need of further study.

TAXONOMIC TREATMENT

The updated infra‐familial classification of Sapindaceae presented below follows the sequence of the clades recovered in our phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 1; Table 1). Four subfamilies are recognized along with 20 tribes distributed as follows: two tribes in Hippocastanoideae, two in Dodonaeoideae, and 16 in Sapindoideae (no tribes are recognized in the monotypic subfamily Xanthoceratoideae). Within Sapindoideae, we formally describe six new tribes, as follows: Blomieae Buerki & Callm. (tribe 13), Guindilieae Buerki, Callm. & Acev.‐Rodr. (tribe 14), Haplocoeleae Buerki & Callm. (tribe 11), Stadmanieae Buerki & Callm. (tribe 19), Tristiropsideae Buerki & Callm. (tribe 10), and Ungnadieae Buerki & Callm. (tribe 5). The descriptions of these new infra‐generic taxa are based predominantly on the benchmark work of Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al. (2011). At this stage, we have not yet identified morphological synapomorphies for five tribes of Sapindoideae, viz. Nephelieae, Sapindeae, Melicocceae, Schleicheraeae, and Cupanieae, so we have therefore based the characterization of each of them on morphological features of its type genus (see Radlkofer, 1931–1934). Our hope is that this revised infra‐familial classification, based on the first near‐comprehensive phylogenetic study of Sapindaceae, will facilitate further research on the family and, in particular, on the poorly known tribes and on the genera placed in incertae sedis.

I. Subfamily Xanthoceratoideae

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 1 of our phylogenetic tree (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes a single genus, Xanthoceras (Fig. 2A).

II. Subfamily Hippocastanoideae

1. Tribe Acereae (Durande) Dumort. Fl. Belg.: 113. 1827. Type: Acer L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to our clade 2 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes two genera, Acer (Fig. 2B) and Dipteronia.

2. Tribe Hippocastaneae (DC.) Dumort. Fl. Belg.: 113. 1827. Type: Aesculus L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 3 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes three genera: Aesculus (Fig. 2C), Billia, and Handeliodendron.

III. Subfamily Dodonaeoideae

3. Tribe Doratoxyleae Radlk. In Sitzungsber. Math.‐Phys. Cl. Königl. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. München 20: 255. 1890. Type: Doratoxylon Thouars ex Hook.f.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 4 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes eight genera: Doratoxylon (Fig. 2D), Exothea, Filicium, Ganophyllum, Hippobromus, Hypelate, Smelophyllum, and Zanha.

4. Tribe Dodonaeae (Kunth) DC. Prodr. 1: 615. 1824. Type: Dodonaea Mill.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 5 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes 16 genera: Arfeuillea, Boniodendron, Conchopetalum, Cossinia, Diplokeleba, Diplopeltis, Dodonaea (Fig. 2F), Euchorium, Euphorianthus, Harpullia, Hirania, Llagunoa, Loxodiscus, Magonia, and Majidea.

IV. Subfamily Sapindoideae

5. Tribe Ungnadieae Buerki & Callm., tribus nov. Type: Ungnadia Endl.

Shrubs or small trees. Leaves alternate, 3‐foliolate or paripinnate, stipule absent. Flowers zygomorphic, functionally unisexual. Sepals 5, imbricate. Petals 4–5, clawed, with a tuft of filiform appendages above the claw; disk wavy; stamens generally 8, glabrous; ovary stipitate, 2–3‐carpellate, ovules 2 per carpel. Fruit a 2‐ or 3‐lobed, loculicidal coriaceous capsule. Seeds without aril.

Note: This new tribe is characterized by zygomorphic flowers with clawed petals bearing a tuft of filiform appendages above the claw, glabrous stamens, and two ovules per carpel. This taxon corresponds to our clade 6 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes two genera, Delavaya (Fig. 3A) and Ungnadia.

6. Tribe Koelreuterieae Radlk. In Sitzungsber. Math.‐Phys. Cl. Königl. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. München 20: 254. 1890. Type: Koelreuteria Laxm.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 7 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes three genera: Erythrophysa (Fig. 2H), Koelreuteria, and Stocksia.

7. Tribe Schleichereae Radlk. In Sitzungsber. Math.‐Phys. Cl. Königl. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. München 20: 253. 1890. Type: Schleichera Willd.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 8 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes six genera: Amesiodendron, Paranephelium (Fig. 2G), Pavieasia, Phyllotrichum, Schleichera, and Sisyrolepis.

8. Tribe Nephelieae Radlk. In Sitzungsber. Math.‐Phys. Cl. Königl. Bayer. Akad. Wiss. München 20: 253. 1890. Type: Nephelium L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 9 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes 16 genera: Aporrhiza, Blighia, Chytranthus, Cubilia, Dimocarpus, Glenniea, Haplocoelopsis, Laccodiscus, Litchi, Nephelium (Fig. 2E), Otonephelium, Pancovia, Placodiscus, Pometia, Radlkofera, and Xerospermum.

9. Tribe Sapindeae (Kunth) DC. Prodr. 1: 607. 1824. Type: Sapindus L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 10 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes 13 genera: Alatococcus, Atalaya, Deinbollia, Eriocoelum, Hornea, Lepisanthes (Fig. 3B), Porocystis, Pseudima, Sapindus, Thouinidium, Toulicia, Tristira, and Zollingeria.

10. Tribe Tristiropsideae Buerki & Callm., tribus nov. Type: Tristiropsis Radlk.

Trees. Leaves alternate, bipinnate. Inflorescences thyrses, axillary, borne towards the end of the branches. Flowers zygomorphic, bisexual or functionally unisexual; sepals 5; petals 5 or absent, clawed, with basal appendages; stamens 8(–13), disc disk annular; ovary 3(–5)‐carpellate with a single ovule per carpel; style sessile, short or elongated; stigma not lobed. Fruit a (2–)3‐locular, an indehiscent drupe; seeds without an arillode.

Notes: This new tribe is characterized by true drupes with a (2–)3‐locular stony layer, a feature that is unique among Sapindaceae. It corresponds to clade 11 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes a single genus, Tristiropsis (Fig. 3C).

11. Tribe Haplocoeleae Buerki & Callm., tribus nov. Type: Haplocoelum Radlk.

Trees and shrubs. Leaves alternate, pinnate. Flowers actinomophic, functionally unisexual; sepals 4–7; petals absent; stamens 4–7; disc hemispherical; ovary 3‐carpelate with a single ovule per carpel; style short, stigma 3‐lobed. Fruits a capsule, 1‐locular, indehiscent to tardily dehiscent; seeds with an aril.

Note: This new tribe is characterized by alternate pinnate leaves, actinomorphic and functionally unisexual flowers, absence of petals, 3‐carpelate ovary with a single ovule per carpel, and fruit that is 1‐locular by abortion with an arillate seed. It corresponds to clade 12 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes two genera, Blighiopsis and Haplocoelum (Fig. 3D).

12. Tribe Melicocceae Blume. Rumphia 3: 142. 1847. Type: Melicoccus P. Browne

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 10 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes four genera: Dilodendron, Melicoccus, Talisia (Fig. 4B), and Tripterodendron.

13. Tribe Blomieae Buerki & Callm., tribus nov. Type: Blomia Miranda

Trees. Leaves alternate, paripinnate. Flowers actinomorphic, unisexual or bisexual; sepals 5, distinct, valvate; petals absent or vestigial, with a pair of minute vestigial appendages; disk annular‐lobed; stamens 5–6; ovary 1‐carpellate with a single ovule per carpel; style short, stigma capitate. Fruit a 1‐locular, tardily loculicidally dehiscent, coriaceous capsule. Seeds with a thin aril.

Note: This new tribe is characterized by paripinnate leaves, petals (when present) with adaxial or marginal appendages (Acevedo‐Rodríguez, 2009), a 1‐carpellate ovary, a coriaceous capsule that is tardily loculicidally dehiscent, and seeds with a thin arillode. It corresponds to clade 14 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes a single genus, Blomia (Fig. 3E).

14. Tribe Guindilieae Buerki, Callm. & Acev.‐Rodr., tribus nov. Type: Guindilia Gillies ex Hook. & Arn.

Shrubs or small trees. Leaves alternate or opposite, simple, entire or tridentate at apex. Flowers zygomorphic, bisexual or functionally unisexual; sepals 5, imbricate; petals 4(–5), with a hood‐shaped, crested, ventral appendage; disk unilateral, 2‐lobed‐pyramidal; stamens 8; pollen colporate, striate; ovary 3‐carpellate with a single ovule per carpel; style filiform, stigma 3‐lobed. Fruit schizocarpic, splitting into (1–)3 subglobose, crustose mericarps. Seed without an aril.

Note: This new tribe is characterized by simple leaves, a unilateral 2‐lobed pyramidal disc, and a schizocarpic fruit that splits into 1–3 subglobose, crustose mericarps (Acevedo‐Rodríguez et al., 2011, 2017). It corresponds to clade 15 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes a single genus, Guindilia (Fig. 3F).

15. Tribe Athyaneae Acev.‐Rodr. Syst. Bot. 42: 108. 2017. Type: Athyana (Griseb.) Radlk.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 16 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes two genera, Athyana (Fig. 4C) and Diatenopteryx.

16. Tribe Bridgesieae Acev.‐Rodr. Syst. Bot. 42: 108. 2017. Type: Bridgesia Bertero ex Cambess.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 17 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes a single genus, Bridgesia (Fig. 4A).

17. Tribe Thouiniaeae Blume. Rumphia 3: 186. 1847. Type: Thouinia Poit.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 18 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes three genera: Allophylastrum, Allophylus, and Thouinia (Fig. 4D).

18. Tribe Paullinieae (Kunth) DC. Prodr. 1: 601. 1824. Type: Paullinia L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 19 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes six genera: Cardiospermum (Fig. 4E), Lophostigma, Paullinia, Serjania, Thinouia, and Urvillea.

19. Tribe Stadmanieae Buerki & Callm., tribus nov. Type: Stadmania Lam. ex. Poir.

Trees and shrubs. Leaves simple, biparipinnate or paripinnate. Corolla actinomorphic or absent, functionally unisexual; sepals 5 or absent; petals 5 or absent, clawed, with basal appendages; stamens 5(6–10); disk annular to 5‐lobed; ovary 3‐carpelate with a single ovule per carpel, style sessile, short or elongated, stigma 2–3‐lobed or with 2–3 stigmatic branches or lines; fruit 1–3 locular, indehiscent or tardily dehiscent. Seeds with an aril.

Note: This new tribe is characterized by actinomorphic flowers (perianth absent in Beguea Capuron, Tsingya Capuron, and Stadmania oppositifolia), petals (when present) with basal appendages, ovary 3‐carpelate with a single ovule per carpel, and a seed covered by an aril. It corresponds to clade 20 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes 10 genera: Beguea, Camptolepis, Chouxia, Gereaua, Macphersonia, Pappea, Plagioscyphus, Pseudopteris, Stadmania (Fig. 4F), and Tsingya.

20. Tribe Cupanieae Blume. Rhumpia 3: 1857. Type: Cupania L.

Note: This taxon corresponds to clade 10 (Table 1; Fig. 1) and includes 36 genera: Alectryon, Arytera, Castanospora, Cnesmocarpon, Cupania, Cupaniopsis, Dictyoneura, Diploglottis, Elattostachys, Eurycorymbus, Gloeocarpus, Gongrodiscus, Gongrospermum, Guioa, Jagera, Lecaniodiscus, Lepiderema, Lepidocupania, Lepidopetalum, Matayba, Mischarytera, Mischocarpus, Molinaea, Neoarytera, Pentascyphus, Podonephelium (Fig. 4G), Rhysotoechia, Sarcopteryx, Sarcotoechia, Scyphonychium, Storthocalyx, Synima, Tina, Toechima, Trigonachras, and Vouarana.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sven Buerki: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Software (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Martin W. Callmander: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Pedro Acevedo‐Rodríguez: Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Porter P. Lowry: Conceptualization (equal); Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Jérôme Munzinger: Data curation (equal); Investigation (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Paul Bailey: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Olivier Maurin: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Grace E. Brewer: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Niroshini Epitawalage: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). William J. Baker: Funding acquisition (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal). Félix Forest: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Writing – original draft (equal); Writing – review & editing (equal).

S.B., M.W.C., and F.F. designed the study and coordinated it with contributions from O.M. and W.J.B.; S.B., M.W.C., J.M., O.M., and P.P.L. collected the data; G.E.B. and N.E. conducted the laboratory work; P.B. and S.B. analyzed the data; S.B., M.W.C., P.B., P.P.L., and F.F. wrote the manuscript; all authors provided input on the manuscript and gave final approval for publication. W.J.B. and F.F. supervised the PAFTOL project at RBG Kew.

Supporting information

APPENDIX S1. Statistics on gene recovery for Sapindaceae accessions included in this study and details on vouchers and ENA accession numbers.

APPENDIX S2. RAxML phylogeny of Sapindaceae based on Angiosperms353 target gene sequences. Clades (Arabic numbers correspond to tribes and Roman numbers to subfamilies) are displayed along with bootstrap support values. See Appendix S1 for more details on species sampling and node support.

APPENDIX S3. ASTRAL phylogeny of Sapindaceae based on nuclear Angiosperms353 target gene sequences. Clades (Arabic numbers correspond to tribes and Roman numbers to subfamilies) are displayed along with node support values. See Appendix S1 for more details on species sampling and node support.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Calleva Foundation and the Sackler Trust to the Plant and Fungal Tree of Life Project (PAFTOL) at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Fieldwork by S.B., M.W.C., J.M., and P.P.L. was supported by the Idaho Botanical Research Foundation. We thank the curators at the following herbaria for making their collections available for our research: BM, BRI, CNS, G, K, KLU, L, MO, MPU, NOU, P, SAR, SAN, SUVA, SING. We are grateful to Michail Belov (http://www.chileflora.com), Philippe Chassot (https://philou.i234.me), Christopher Davidson (https://floraoftheworld.org), Claire De Schrevel, G. Curt Fiedler (http://www.umijin.com), Olga Martha Montiel, Diosdado Nguema, Pete Phillipson, Charles Rakotovao, and Germaine A. Parada for permission to reproduce their photos, and to Roy Gereau for advice regarding Latin. We especially express our gratitude to Christopher Davidson and Sharon Christoph for their constant support and interest in our research. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of this paper.

Buerki, S., Callmander M. W., Acevedo‐Rodriguez P., Lowry P. P. II, Munzinger J., Bailey P., Maurin O., Brewer G. E., Epitawalage N., Baker W. J., Forest F.. 2021. An updated infra‐familial classification of Sapindaceae based on targeted enrichment data. American Journal of Botany 108(7): 1234–1251.

DATA AVAILABILITY