Abstract

Wall teichoic acids (WTAs) are important components of the cell wall of the opportunistic Gram‐positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. WTAs are composed of repeating ribitol phosphate (RboP) residues that are decorated with d‐alanine and N‐acetyl‐d‐glucosamine (GlcNAc) modifications, in a seemingly random manner. These WTA‐modifications play an important role in shaping the interactions of WTA with the host immune system. Due to the structural heterogeneity of WTAs, it is impossible to isolate pure and well‐defined WTA molecules from bacterial sources. Therefore, here synthetic chemistry to assemble a broad library of WTA‐fragments, incorporating all possible glycosylation modifications (α‐GlcNAc at the RboP C4; β‐GlcNAc at the RboP C4; β‐GlcNAc at the RboP C3) described for S. aureus WTAs, is reported. DNA‐type chemistry, employing ribitol phosphoramidite building blocks, protected with a dimethoxy trityl group, was used to efficiently generate a library of WTA‐hexamers. Automated solid phase syntheses were used to assemble a WTA‐dodecamer and glycosylated WTA‐hexamer. The synthetic fragments have been fully characterized and diagnostic signals were identified to discriminate the different glycosylation patterns. The different glycosylated WTA‐fragments were used to probe binding of monoclonal antibodies using WTA‐functionalized magnetic beads, revealing the binding specificity of these WTA‐specific antibodies and the importance of the specific location of the GlcNAc modifications on the WTA‐chains.

Keywords: antibodies, automated synthesis, gram-positive bacteria, ribitol phosphate, wall teichoic acids

By using tailor‐made teichoic acid building blocks, a library of glycosylated ribitol phosphate Staphylococcus aureus wall teichoic acids (WTA) has been assembled, ranging in length, and varying in N‐acetyl glucosamine substitution pattern. The library of well‐defined WTAs has been used to develop a magnetic bead binding assay to interrogate monoclonal antibody binding, revealing the preference of the various antibodies for different glycosylation patterns.

Introduction

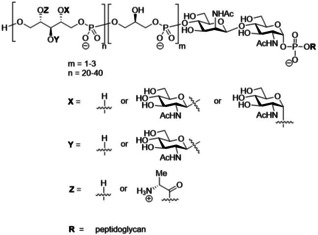

The Gram‐positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is a common member of the human microbiome and is commonly found on the skin and in the nares. When entering the blood stream or internal tissues, S. aureus can cause serious infections, for which immunocompromised patients are especially at risk.[1] Extensive use of antibiotics has resulted in increased resistance among S. aureus strains against commonly‐used antibiotics leading to infections that are difficult to treat. Currently, methicillin ‐resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is the most commonly identified antibiotic‐resistant pathogen in clinical medicine worldwide.[2] The spread of MRSA highlights the urgent need for alternative therapies, such as passive or active vaccination.[3] Wall teichoic acids (WTAs) are prime constituents of the Gram‐positive cell wall and can function as effective antigenic epitopes. WTAs are therefore promising candidates for the development of a conjugate vaccine against S. aureus infections.[4] WTAs are anionic poly(ribitol phosphate) (RboP) chains covalently attached to the thick peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall. They are involved in a plethora of vital bacterial functions including host interaction, biofilm formation, autolysin activity and their overexpression can increase bacterial virulence.[5] The ribitol residues that are interconnected through phosphodiester linkages, can be substituted in a seemingly random manner with d‐alanine (d‐Ala) on C2, α/β‐N‐acetyl‐d‐glucosamine (GlcNAc) on C‐4 or a β‐GlcNAc on C‐3. The GlcNAc residues are introduced by three dedicated glycosyltransferases, TarS[6] (1,4‐β‐GlcNAc), TarM[7] (1,4‐α‐GlcNAc), and the recently discovered TarP[8] (1,3‐β‐GlcNAc), respectively (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of S. aureus WTA structure.

To unravel the roles of WTAs in biology at the molecular level, well‐defined fragments are indispensable tools. Since isolation from the bacteria leads to heterogenous mixtures of fragments and bacterial contaminations, organic synthesis is the method of choice to generate WTA‐fragments with pre‐defined substitution pattern. Because the WTA fragments are built up from repeating units interconnected through phosphodiester linkages, well‐established DNA chemistry can be used to assemble the target compounds, also offering the possibility for automation. Over the years, several approaches have been reported for the assembly of both WTAs as well as the structurally‐related lipoteichoic acids (LTAs). We have reported on different strategies to assemble glycerol phosphate‐based LTA fragments, including solution phase, fluorous‐tag based and automated solid phase syntheses.[9] The synthesis of RboP WTA fragments has been described before by the groups of Pozsgay,[10] Lee,[11] and Driguez,[4b] each building on the use of phosphoramidite chemistry. Pozsgay and Lee however reported that automation of their syntheses was unsuccessful. We here report on the development of chemistry that allows for the generation of well‐defined unsubstituted RboP oligomers, using both solution and automated solid phase synthesis (ASPS) techniques. All fragments are equipped with an aminohexanol spacer for conjugation purposes. Taking into account that bacterial WTA is covalently attached to peptidoglycan at the RboP C1‐position, this is also the attachment site for the linker in the synthetic fragments. We have equipped the synthetic fragments with a biotin handle, and we have used these to functionalize streptavidin coated, magnetic beads to generate WTA beads that have been used to characterize the binding of several monoclonal antibodies at the molecular level.[12] These binding studies have cleanly revealed the binding specificity and differences between these antibodies, not only showing clear differences between monoclonal antibodies recognizing the α‐ or β‐linked GlcNAc ribitolphosphates, but also selectivity between the regioisomeric β‐GlcNAc WTA fragments. The synthetic WTA oligomers thus represent valuable tools in mapping binding specificity of host receptor molecules at the molecular level.

Results and Discussion

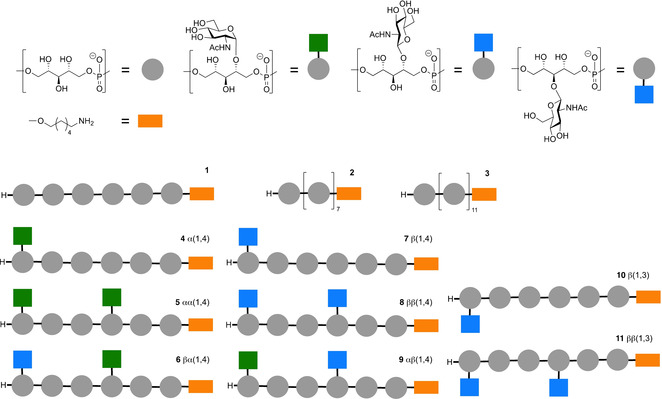

The set of compounds, generated for this study is depicted in Figure 2. All fragments are functionalized with an aminohexanol spacer for conjugation purposes. We have previously described that a glycosylated glycerol phosphate hexamer LTA fragment can be used as an adequate synthetic antigen in the development of vaccines against Enterococcus faecalis.[13] We therefore decided to target a set of glycosylated ribitol phosphate WTA hexamers. In addition, we aimed to assemble longer non‐substituted fragments through automated synthesis. The set thus comprises RboP‐WTA chains carrying no carbohydrate substituents varying in length from a hexamer (1) to an octamer (2) and a dodecamer (3). Different carbohydrate decoration patterns have been introduced (α‐GlcNAc or β‐GlcNAc residues can be mounted on the C4‐hydroxy groups of the RboP‐monomers or the RboP C3‐hydroxy can carry a β‐GlcNAc) and we decided to mount a single GlcNAc residue at the terminal RboP residue, or two GlcNAc residues at the third and the sixth RboP. Besides the hexamers carrying a single type of carbohydrate appendage, we also generated two hexamers having both an α‐(1,4)‐GlcNAc and a β‐(1,4)‐GlcNAc on the RboP‐chain, leading to the following set of target compounds: α(1,4) 4, and αα(1,4) 5, βα(1,4) 6, β(1,4) 7, ββ(1,4) 8, αβ(1,4) 9, β(1,3) 10 and ββ(1,3) 11.

Figure 2.

The library of RboP‐WTA structures, generated for this study.

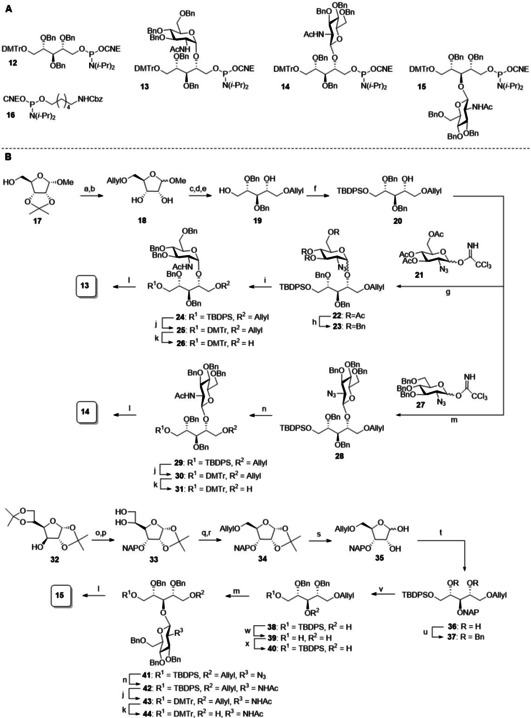

Synthesis of building blocks

The building blocks that we designed for the assembly of the target compounds are depicted in Scheme 1A. The ribitol phosphate building blocks feature a temporary dimethoxytrityl group to mask the primary alcohol that is to be elongated during the chain elongation and a cyanoethyl phosphoramidite functionality. Ribitol building blocks 13, 14 and 15 carry an α‐(1,4), β‐(1,4) and β‐(1,3)‐linked N‐acetyl glucosamine appendage, respectively, and the carbohydrate moieties in these building blocks only carry benzyl ether protecting groups to allow for the global deprotection of the fragments using mild hydrogenation conditions. We used phosphoramidite hexanolamine 16 [9a] to introduce the amino linker in the molecules.

Scheme 1.

Assembly of building blocks. a) AllylBr, NaH, THF/DMF (7 : 1), 0 °C to rt; b) AcOH/H2O 1 : 1, 50 °C, 300 mbar, 62 % over 2 steps; c) BnBr, NaH, THF/DMF (7 : 1), 0 °C to rt; d) 4 M HCl dioxane, 80 °C; e) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C, 50 % over 3 steps; f) TBDPSCl, TEA, DCM 0 °C to rt, 95 %. g) 21, TMSOTf, DCM, rt, 92 %, 7 : 1 α/β; h) i. NaOMe, MeOH, rt, 70 % α‐anomer; ii) BnBr, NaH, THF/DMF (7 : 1), 0 °C to rt, 73 %; i) i. PMe3, KOH, THF; ii. Ac2O, pyridine, 24: 89 % over 2 steps; j) i. TBAF, THF, rt; ii) DMTrCl, TEA, DCM, 25: 67 %; 30: 36 %; 43: 60 %; k) i. Ir(COD)(Ph2MeP)2PF6, H2, THF, ii. I2, sat. aq. NaHCO3, THF, 26: 88 %; 31: 79 %; 44: 94 %; l) 2‐cyanoethyl‐N,N‐diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, DIPEA, DCM, 13: 81 %; 14: 78 %; 15: 85 %; m) 27, TMSOTf, ACN, −40 °C to 0 °C, 28: 85 %; 41: 80 %; n) propanedithiol, pyridine, H2O, TEA, rt; ii. Ac2O, pyridine, 29: 59 % 2 steps; 42: 86 %; o) i. DMSO, Ac2O; ii. NaBH4, EtOH/H2O, 69 % over 2 steps; iii. NAPBr, NaH, TBAI, THF; p) p‐TsOH⋅H2O, MeOH, 75 % over 2 steps; q) i. 0.2 M NaIO4 in H2O, ethylene glycol, MeOH; ii. NaBH4, MeOH; r) AllylBr, NaH, THF/DMF, 88 %; s) THF/H2O/formic acid, 85 %; t) i. NaBH4, MeOH; ii. TBDPSCl, TEA, DCM, 57 % over 2 steps; u) BnBr, NaH, THF/DMF; v) DDQ, DCM/H2O; w) TBAF, THF, 62 % over 2 steps; x) TBDPSCl, TEA, DCM, 98 %.

The synthesis of ribitol phosphoramidite 12 was accomplished as described by Hermans et al.[14] Scheme 1B depicts the synthesis of the glycosylated building blocks 13, 14 and 15. The synthesis of the required C4‐OH ribitol 20, started from ribose 17 by allylation of the primary alcohol, followed by isopropylidene hydrolysis to yield 18. Benzylation and ensuing acidic hydrolysis of the methyl acetal yielded the corresponding lactol intermediate, which was reduced using sodium borohydride to provide primary alcohol 19. Protection with a TBDPS group then gave acceptor 20. Driguez and Lee previously described the use of a glycosylation strategy in which a mixture of α‐ and β‐N‐acetyl glucosamine was generated. We set out to develop stereoselective glycosylation methodology to streamline the assembly of the glycosylated building blocks.

The assembly of the α‐linked GlcNAc building block was accomplished using glucosazide donor 21, which was coupled with acceptor 20 to yield 22 as a 7 : 1 α/β‐mixture. The two anomers could be separated after Zemplén deacetylation, leading to the pure α‐product 23 in 70 % yield.[15] Benzylation of the liberated alcohols, followed by Staudinger reduction and subsequent acetylation of the amine yielded 24 in 89 % yield over 3 steps. Next the TBDPS group was exchanged for a 4,4′‐Dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) group to afford 25. The removal of the allyl ether was accomplished by the iridium catalyzed allyl isomerization and iodine mediated enol ether hydrolysis, under slightly basic conditions to deliver alcohol 26, which was functionalized with a cyanoethyl phosphoramidite to give the building block 13 in 81 % yield.

The corresponding β‐GlcNAc building block was generated through the union of tribenzyl glucosazide donor 27 and acceptor 20. The use of acetonitrile as a β‐directing solvent in combination with a low reaction temperature ensured the stereoselective formation of the desired β‐glucosamine linkage and 28 was obtained in 85 %.[16] Similar protecting group manipulations as described for the α‐GlcNAc ribitol then delivered the required β‐GlcNAc building block 14.

The synthesis of the β‐(1,3)‐GlcNAc‐functionalized ribitol phosphoramidite 15 required the generation of C3‐OH ribitol 40.

To this end, diacetone‐d‐glucose 32 was transformed into the corresponding allose, having the required ribose stereochemistry, through a well‐established[17] oxidation‐reduction sequence in 69 % yield. Naphthylation then gave the fully protected allofuranose and regioselective removal of the 5,6‐isopropylidene group using p‐TsOH in MeOH provided compound 33 in 75 % over 2 steps. Next, oxidative cleavage of the 5,6‐diol with NaIO4 gave the aldehyde, which was reduced to form the primary alcohol. Allylation of this alcohol, afforded ribose 34 with a yield of 88 % over 3 steps. Subsequently, the 1,2‐isopropylidene was cleaved under acidic conditions to give 35. Reductive opening of hemiacetal 35, and TBDPS protection of the primary alcohol then provided 36. Benzylation of the remaining alcohols led to fully protected ribitol 37. During this alkylation step, a byproduct formed, due to TBDPS migration and this product could not be separated from the desired product at this stage. Therefore, the naphthyl ether and TBDPS ethers were removed to provide 38, which could be purified from the formed byproduct yielding product 39 in 62 % yield over 3 steps. Reinstallation of the TBDPS group on the primary alcohol furnished the C3‐OH ribitol building block 40.

The glycosylation of 40 was accomplished using donor 27 and the reaction conditions described above delivered the glucosamine ribitol 41 as a single anomer in 80 % yield. This synthon was uneventfully transformed into the desired β‐(1,3)‐GlcNAc ribitol phosphoramidite 15 using the protecting and functional group manipulations described above.

Assembly of RboP WTA fragments

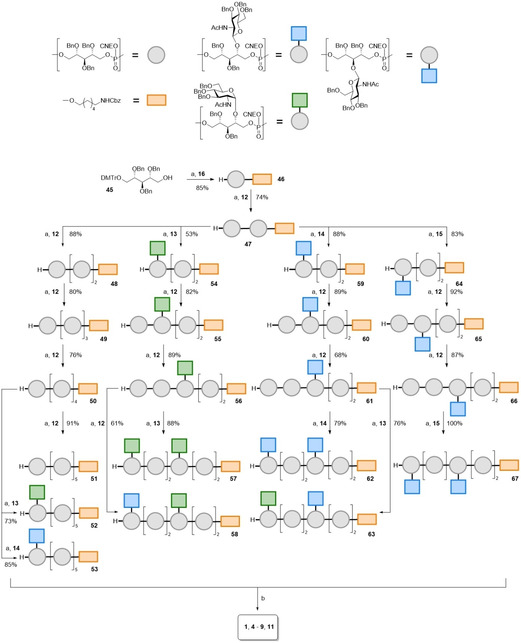

Solution phase synthesis of RboP WTA fragments

With all required building blocks in hand, we set out to generate the set of target structures, using a solution phase synthesis approach depicted in Scheme 2. First the coupling chemistry was explored in the synthesis of non‐substituted hexamer 1. The RboP‐chain elongation steps using phosphoramidite condensations consisted of 3 steps. In the first step the amidite was activated under agency of 4,5‐dicyanoimidazole (DCI) to enable attack by the primary ribitol alcohol to form the phosphite intermediate, which was oxidized in the next step using (10‐camphorsulfonyl)oxaziridine (CSO). Detritylation using 3 % dichloroacetic acid (DCA) in DCM liberated the primary alcohol and silica gel column chromatography yielded the pure ribitol phosphate fragment, ready for the next elongation step. Starting with ribitol 45 [14] and spacer amidite 16, monomer 46 was obtained in 85 % yield. From alcohol 46 the coupling cycles were repeated five times to yield 47–51, all in good yield. Next, we incorporated the glycosylated building blocks in the synthetic scheme, generating the hexamers with one or two GlcNAc residues. All chain elongation events proceeded uneventfully and the yields for all coupling cycles are summarized in Scheme 2. The presence of the carbohydrate appendages did not seem to influence the efficiency of the condensation chemistry, reaffirming the power of phosphoramidite chemistry to assemble this type of biopolymer fragments. Deprotection of the fragments was accomplished by first removing the cyanoethyl groups to deliver the corresponding phosphate diesters followed by hydrogenation to remove all benzyl groups. All target compounds were obtained after gel permeation size exclusion purification and sodium ion exchange.

Scheme 2.

Assembly of the target WTA‐oligomers. Reagents and conditions: a) i. DCI, ACN, phosphoramidite 12, 13, 14 or 15; ii. CSO; iii. 3 % DCA in DCM. b) i. NH3 (30‐33 % aqueous solution), dioxane; ii. Pd black, H2, AcOH, H2O/dioxane, 1: 87 %; 4: 96 %; 5: 55 %; 6: 16 %; 7: 68 %; 8: 78 %; 9: 88 %; 11: 70 %.

Automated solid phase synthesis of RboP WTA fragments

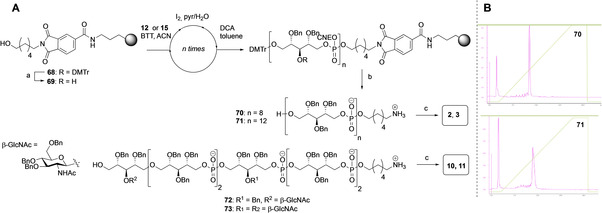

Finally, we investigated the possibility to assemble RboP‐WTA oligomers using an automated solid phase approach (Scheme 3). To this end, we selected the commercially‐available controlled pore glass (CPG) resin 68 that carries a phthalimide protected aminohexanol spacer. Previously, Pozsgay and co‐workers described that an intractable mixture was obtained in the attempted automated solid phase synthesis of a RboP‐octa‐ and dodecamer.[10] As suggested by the authors, this could have been caused by the high concentration of TCA used to remove the DMTr groups. In our solution phase syntheses described above, we used a milder acid, DCA, for the removal of the DMTr group and these conditions were here translated to the solid phase. The syntheses were performed on an Äkta oligopilot plusTM synthesizer on 10 μmol scale (Scheme 2). The DMTr group was cleaved from resin 68 using 3 % DCA in toluene and the coupling with cyanoethyl (CNE) amidite 12 under 5‐(Benzylthio)‐1H‐tetrazole (BTT) activation then provided the resin bound phosphite. Oxidation using I2 in pyridine/H2O yielded the phosphate triester after which a capping step took place to prevent any unreacted alcohol functionalities to react in the next step, which could lead to byproducts that are difficult to separate. Removal of the DMTr group allowed a new cycle to start and the coupling cycles were repeated 7 and 11 times to reach the target octa‐ and dodecamer. Treatment of the resin with 3 % DCA unmasked the primary alcohol and subsequent treatment with aqueous 25 % NH3 cleaved the cyanoethyl groups and released the oligomers from the resin. Scheme 3B depicts the LCMS chromatogram of the crude products 70 and 71, indicating highly efficient syntheses of these oligomers. Purification of the crude oligomers by reversed phase HPLC and desalting afforded 70 and 71 in 15 % and 11 % yield respectively. Hydrogenation of the semi‐protected octa‐ and dodecamer yielded the targets 2 and 3 both in quantitative yields. We also probed the use of GlcNAc carrying building blocks in the automated solid phase synthesis and assembled hexamers 10 and 11, having either one or two β‐(1,3)‐GlcNAc appendages. Also these syntheses proceeded uneventfully, as judged from the amount of released DMT‐groups and the benzyl protected target hexamers 72 and 73 were obtained in 20 % and 11 % yield, after reversed HPLC and a desalting step. Final hydrogenolysis of the semi‐protected hexamers gave the target structures 10 and 11 in 87 % and quantitative yield, respectively.

Scheme 3.

Automated solid phase assembly of WTA‐fragments. Reagents and conditions: a) 3 % DCA in toluene (3 min); 12 or 15 BTT, ACN (5 min); I2, pyr/H2O (1 min); Ac2O, N‐methylimidazole, 2,6‐lutidine, ACN (0.2 min); b) 25 % NH3 (aq) (60 min); 70: 15 %; 71: 11 %; 72: 20 %; 73: 11 %; c) Pd black, H2, dioxane H2O, AcOH, 2: 100 %; 3: 100 %; 10: 87 %; 11: 100 %.

Characterization of glycosylated hexamers

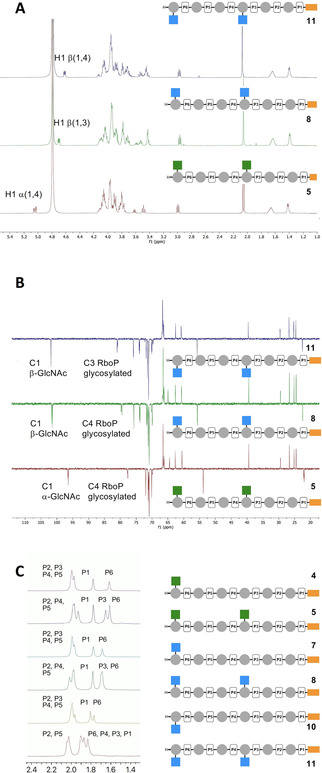

We characterized the assembled oligomers by 1H, 13C and 31P NMR and Figure 3 depicts the 1H and 13C spectra of the WTA hexamers carrying two α‐1‐4‐, β‐1,4‐ or β‐1,3‐GlcNAc residues, namely compounds 5, 8, and 11. The NMR spectra of these well‐defined WTAs can be very useful for the structure determination of new WTA‐species isolated from bacterial strains, in particular the position and configuration of these modifications along the chain. As shown in Figure 2A, the anomeric protons of the α‐linked GlcNAc (in 5) are present at a different chemical shift value than the anomeric protons of the β‐GlcNAc (in 8 and 11). The β‐1,3‐GlcNAc anomeric protons appear at 4.62 ppm, slightly lower than the β‐1,4‐GlcNAc anomeric protons with resonances at 4.70 ppm. These values are in accordance with those reported by Driguez and co‐workers[4b] for β‐1,3‐GlcNAc modified WTA, isolated from strain ATC 55804 with an anomeric value of 4.65 and with β‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA isolated from strain Wood 46 showing anomeric signals at 4.75 ppm. The reported anomeric signals for α‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA from Newman D2C 5.07 (at 5.04 ppm) also agree well with the values for the α‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA (5.03 ppm and 5.06 ppm). The values are also well in line with the TarP and TarM modified WTAs described by Gerlach et al.[8]

Figure 3.

Characterization of the synthetic WTA‐fragments. A) 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) of 5, 8 and 11. B) 13C NMR (126 MHz, D2O) of 5, 8 and 11. C) 31P NMR (202 MHz, D2O, 10 mg/mL, pH 7) of 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 11.

Figure 2B shows the 13C NMR of the WTAs 5, 8 and 11. The anomeric signals of the β‐1,3‐GlcNAc WTA 11 appear at 101.6 and the C3 glycosylated Rbo 11 shows a shift for the ribitol C3 at 80.8 and 81.0 which is in agreement with the previously reported data, which described a chemical shift of 81.8 ppm for this carbon, appearing at a higher ppm value than the non‐glycosylated ribitol positions.[8] The β‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA 8 anomeric shifts can be found at 101.4 ppm and 101.6 ppm, comparable to the β‐1,3‐GlcNAc anomeric signals. The Rbo C4 of this β‐1,4‐glycosylated hexamer appear around 79.4‐79.9, which is in accordance with the value previously reported (δ=80.8 ppm) for glycosylated C‐4 RboP‐carbon atoms. The anomeric signals corresponding to the α‐1‐4‐GlcNAc WTA 5 appear at 96.4 ppm and 96.5 ppm. This smaller chemical shift is expected for α‐glycosidic linkages and the RboP C4 can be found at 77.6–77.8 ppm.

31P NMR spectra have previously not been described for different glycosylated WTA oligomers. As depicted in Figure 2C, comparing the 31P NMR spectra of the α‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA, β‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA and β‐1,3‐GlcNAc WTA hexamers, it appears that the 31P‐chemical shift is diagnostic for the type of GlcNAc appendage. The 31P signals are assigned P1 to P6 , as shown in the schematic structure diagrams next to the spectra. The spectrum of the αα‐1,4‐GlcNAc hexamer 5 shows three types of signals: three around 2 ppm, a single peak at 1.8 ppm and two peaks around 1.7 ppm. Considering that the phosphate next to the spacer will be different from the other phosphate diesters that are all flanked by two ribitol residues the single peak likely corresponds to the phosphate diester attached to the spacer. When the spectra of the α‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐ and αα‐1,4‐GlcNAc hexamers 4 and 5, respectively, are compared it becomes clear that one peak has shifted to a lower ppm value. This phosphorous resonance thus likely corresponds to P3 . This analysis also holds for the β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐ and ββ‐1,4‐GlcNAc hexamers 7 and 8, which show a similar chemical shift pattern. The 31P‐spectrum of the β‐1,3 glycosylated WTAs 10 and 11 shows similarity to the β‐1,4‐ and α‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTAs. The introduction of the second GlcNAc substituent at the third ribitol residue causes the resonance of the phosphate diesters P3 and P4 (which are equally close to the GlcNAc residue in the middle of the RboP moiety) to shift to a lower chemical shift: the peaks around 1.8–1.9, corresponding to four P signals, belong to P1 , P3 , P4 and P6 . The phosphodiesters, flanked by two non‐substituted ribitols are found around 2 ppm. In all, this analysis shows that 31P NMR chemical shifts can be diagnostic for the substitution pattern along the RboP chain, and the relative intensity of the signals indicative for the degree of glycosylation.

Antibody binding

With the synthetic WTA fragments in hand, we set out to develop an assay to interrogate antibody binding. Recently, Lupardus and co‐workers have described the development of different monoclonal antibodies, generated from B‐cells of S. aureus infected patients.[18] Structural studies were performed with these mAbs using X‐ray crystallography on a monomeric β‐1,4‐GlcNAc ribitol phosphate fragment and binding studies were performed with whole bacteria, using biosynthesis knock‐out strains to unravel the role of the WTA‐glycosylation pattern.[19] The availability of our synthetic fragments now allows for direct binding studies at the molecular level. We have recently described the development of a magnetic bead assay to study the deposition of antibodies through binding of enzymatically glycosylated WTA fragments.[12] We here used the same set up and equipped the synthesized hexamers with a biotin handle, exploiting the amine function of the hereto introduced amino spacer (Figure 4A). Next, streptavidin‐coated magnetic dynabeads M280 were functionalized with the biotinylated hexamers and then interrogated using monoclonal antibodies, generated to recognize α‐GlcNAc functionalized RboP WTAs (clone 4461 and clone 4624) or β‐1,4‐GlcNAc carrying RboP WTAs (clones 4497 and 6292).

Figure 4.

Magnetic WTA‐beads for antibody binding assays. A) Workflow for the antibody binding assay: 1) Biotinylation of WTA fragments 4–11; 2) Adsorption on streptavidin coated M280 Dynabeads; 3) binding of monoclonal antibodies; 4) Alexa 488‐Protein G conjugation; 5) Readout of fluorescent beads. B–E) Binding of monoclonal antibody B) 4461, C) 4624, D) 4497 and E) 6292 to the WTA‐functionalized beads.

As can be seen in Figure 4B, mAb 4461 binds to the beads functionalized with the WTA fragments carrying an α‐GlcNAc appendage 4 and 5. The non‐glycosylated RboP‐hexamers or the hexamers carrying β‐GlcNAc‐residues are not recognized by this antibody. A single α‐GlcNAc‐functionality (as in 4) seems to be sufficient for binding, but the beads functionalized with two α‐GlcNAc‐residues (as in 5) show increased binding. The presence of a β‐1,4‐GlcNAc in the WTA fragments does not interfere with binding as the αβ‐1,4 (9) and βα‐1,4 (6) functionalized beads both show deposition of the antibody. Interestingly the αβ‐1,4‐GlcNAc 9 functionalized beads show less antibody binding than the corresponding βα‐1,4 (6) derivatized beads. This may indicate that the mAb binds better to “internal” α‐GlcNAc‐residues than to an α‐GlcNAc at the terminus of the WTA chain. The analysis of clone 4624 provides a nearly identical picture: α‐GlcNAc‐functionalized WTA fragments are selectively recognized with a single sugar residue being the minimal requirement for binding (Figure 4C). Also this mAb seems to have a preference for internal α‐GlcNAc‐residues.

Clones 4497 and 6292 have been identified to recognize β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐WTA and Figure 4D shows that 4497 binds to all WTA‐hexamers carrying a β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐residue. A single β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐moiety seems to be sufficient for binding and there does not seem to be a strong preference for the position of the β‐1,4‐GlcNAc on the WTA chain. This mAb also binds to the regioisomeric β‐1,3‐GlcNAc epitopes (11), indicating that this mAb is cross‐reactive to TarP‐expressing S. aureus. The binding to the β‐1,3‐GlcNAc‐WTA fragment 11 is however, significantly weaker than binding to its β‐1,4‐counterpart 8. The binding assays using clone 6292 (Figure 4E) show that the synthetic fragments are poorly recognized by this mAb. In contrast, the hexamers glycosylated using the β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐transferase TarS do induce antibody deposition on the beads. The hexamers that have been enzymatically glycosylated have a higher density of β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐residues (an average of 3–4 GlcNAc residues per hexamer) indicating that this mAb either binds preferentially to WTA fragments carrying multiple β‐1,4‐GlcNAc‐residues in close proximity or that the affinity of this mAb is lower and thus requires the simultaneous presentation of multiple epitopes, within the same WTA‐fragment.

Conclusion

We describe here a synthetic chemistry approach to assemble all currently known glycosylation types of S. aureus RboP WTAs. We have developed stereoselective glycosylation reactions to generate building blocks that have been used to assemble α‐1,4, β‐1,4 and β‐1,3‐GlcNAc functionalized RboP‐WTAs. A strategy was used employing phosphoramidite chemistry in combination with DMTr‐protected building blocks. This “DNA‐type” chemistry was successfully transposed to an automated solid phase format, significantly streamlining the assembly of longer WTA fragments. Detailed spectroscopic analysis of the fragments has revealed diagnostic signals that can be used as reference for future WTA‐structure elucidation studies. Finally, we have shown the applicability of the synthetic WTA‐fragments in the development of a binding assay to map binding interactions of anti‐WTA monoclonal antibodies at the molecular level. These interaction studies have shown that antibodies that recognize β‐1,4‐GlcNAc WTA can be cross‐reactive with β‐1,3‐GlcNAc WTA. It is thus likely that IgG in human serum is also capable of interacting with both TarS‐WTA and TarP‐WTA, as described by Van Dalen et al.[12] More detailed binding studies are required to pinpoint the differences in binding between the two different epitopes and the (recombinantly expressed) monoclonal antibodies or human sera. It is expected that raising antibodies against S. aureus TarP‐WTA, or a synthetic conjugate featuring this WTA‐type will lead to specific anti‐β‐1,3‐GlcNAc‐WTA antibodies. Alternatively, structure‐guided antibody engineering may open up avenues to generate selective and tight binding WTA‐glycosylation type specific antibodies. Well‐defined WTA fragments are valuable tools to delineate clear structure‐activity relationships and will be used in the future to characterize antibody binding epitopes and to probe binding to other receptors, such as C‐type lectins and unravel the mode of action of biosynthesis enzymes at the molecular level.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Simone Nicolardi and Fabrizio Chiodo for MALDI measurements. Carla de Haas and Piet Aerts for technical assistance with recombinant antibody production. This work was supported by Vidi (91713303) and Vici (09150181910001) grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW) to N.M.v.S.

S. Ali, A. Hendriks, R. van Dalen, T. Bruyning, N. Meeuwenoord, H. S. Overkleeft, D. V. Filippov, G. A. van der Marel, N. M. van Sorge, J. D. C. Codée, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10461.

References

- 1.Lowy F. D., N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harkins C. P., Pichon B., Doumith M., Parkhill J., Westh H., Tomasz A., De Lencastre H., Bentley S. D., Kearns A. M., Holden M. T. G., Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daum R. S., Spellberg B., Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a.A. Fattom, (Nabi Biopharmaceuticals), WO 2007/053176 A2, 2007;

- 4b.P.-A. G. Driguez, (Sanofi Pasteur), WO 2017/064190 A1, 2017;

- 4c.Adamo R., Nilo A., Castagner B., Boutureira O., Berti F., Bernardes G. J., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuhaus F. C., Baddiley J., Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sobhanifar S., Worrall L. J., King D. T., Wasney G. A., Baumann L., Gale R. T., Nosella M., Brown E. D., Withers S. G., Strynadka N. C., PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1006067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sobhanifar S., Worrall L. J., Gruninger R. J., Wasney G. A., Blaukopf M., Baumann L., Lameignere E., Solomonson M., Brown E. D., Withers S. G., Strynadka N. C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerlach D., Guo Y., De Castro C., Kim S. H., Schlatterer K., Xu F. F., Pereira C., Seeberger P. H., Ali S., Codee J., Sirisarn W., Schulte B., Wolz C., Larsen J., Molinaro A., Lee B. L., Xia G., Stehle T., Peschel A., Nature 2018, 563, 705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a.Hogendorf W. F., Bos L. J., Overkleeft H. S., Codee J. D., Marel G. A., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 3668; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b.van der Es D., Hogendorf W. F., Overkleeft H. S., van der Marel G. A., Codee J. D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1464; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c.van der Es D., Berni F., Hogendorf W. F. J., Meeuwenoord N., Laverde D., van Diepen A., Overkleeft H. S., Filippov D. V., Hokke C. H., Huebner J., van der Marel G. A., Codee J. D. C., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 4014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d.Hogendorf W. F., Lameijer L. N., Beenakker T. J., Overkleeft H. S., Filippov D. V., Codee J. D., Van der Marel G. A., Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 848; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e.Hogendorf W. F., Kropec A., Filippov D. V., Overkleeft H. S., Huebner J., van der Marel G. A., Codee J. D., Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 356, 142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fekete A., Hoogerhout P., Zomer G., Kubler-Kielb J., Schneerson R., Robbins J. B., Pozsgay V., Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung Y. C., Lee J. H., Kim S. A., Schmidt T., Lee W., Lee B. L., Lee H. S., Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dalen R., Molendijk M. M., Ali S., van Kessel K. P. M., Aerts P., van Strijp J. A. G., de Haas C. J. C., Codée J., van Sorge N. M., Nature 2019, 572, E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laverde D., Wobser D., Romero-Saavedra F., Hogendorf W., van der Marel G., Berthold M., Kropec A., Codee J., Huebner J., PLoS One 2014, 9, e110953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans J. P. G., Poot L., Kloosterman M., van der Marel G. A., van Boeckel C. A. A., Evenberg D., Poolman J. T., Hoogerhout P., van Boom J. H., Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 1987, 106, 498. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa-Perez I., Stadelmaier A., Morath S., Hartung T., Schmidt K. R., Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 493. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a.Tsuda T., Nakamura S., Hashimoto S., Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 10711; [Google Scholar]

- 16b.Pougny J.-R., Sinaÿ P., Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 4073; [Google Scholar]

- 16c.Schmidt R. R., Behrendt M., Toepfer A., Synlett 1990, 11, 694; [Google Scholar]

- 16d.Schmidt R. R., Rücker E., Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 1421; [Google Scholar]

- 16e.Mulani S. K., Hung W. C., Ingle A. B., Shiau K. S., Mong K. K., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 1184; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16f.Khatuntseva E. A., Sherman A. A., Tsvetkov Y. E., Nifantiev N. E., Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 708; [Google Scholar]

- 16g.Demchenko A. V., Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation; A. V. Demchenko, Ed.Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA ,: Weinheim, Germany, 2008, pp. 10–11; [Google Scholar]

- 16h.van der Es D., Groenia N. A., Laverde D., Overkleeft H. S., Huebner J., van der Marel G. A., Codee J. D., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sowa W., Thomas G. H. S., Can. J. Chem. 1966, 44, 836. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong R., Kajihara K., Chen M., Hotzel I., Mariathasan S., Hazenbos W. L. W., Lupardus P. J., mAbs 2018, 10, 979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J.-H., Kim N.-H., Winstel V., Kurokawa K., Larsen J., An J.-H., Khan A., Seong M.-Y., Lee M. J., Andersen P. S., Peschel A., Lee B.-L., Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary