Abstract

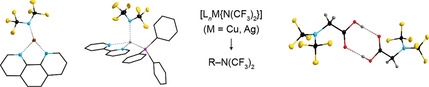

Fluorinated groups are essential for drug design, agrochemicals, and materials science. The bis(trifluoromethyl)amino group is an example of a stable group that has a high potential. While the number of molecules containing perfluoroalkyl, perfluoroalkoxy, and other fluorinated groups is steadily increasing, examples with the N(CF3)2 group are rare. One reason is that transfer reagents are scarce and metal‐based storable reagents are unknown. Herein, a set of CuI and AgI bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes stabilized by N‐ and P‐donor ligands with unprecedented stability are presented. The complexes are stable solids that can even be manipulated in air for a short time. They are bis(trifluoromethyl)amination reagents as shown by nucleophilic substitution and Sandmeyer reactions. In addition to a series of benzylbis(trifluoromethyl)amines, 2‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amino acetate was obtained, which, upon hydrolysis, gives the fluorinated amino acid N,N‐bis(trifluoromethyl)glycine.

Keywords: amination, copper, fluorinated ligands, N ligands, silver

Stable storage solutions: Copper(I) and silver(I) complexes with the bis(trifluoromethyl)amido ligand stabilized by pyridine and phosphane ligands have become accessible. These complexes are thermally stable and can be stored under inert conditions; in contrast to the behavior of other metal salts such as M{N(CF3)2} (M=Cu, Ag). The complexes were found to be convenient reagents for nucleophilic substitution and Sandmeyer reactions, thereby providing access to a series of organic substrates with the bis(trifluoromethyl)amino group.

Transition metal perfluoroalkyl complexes are highly valuable reagents for the synthesis of fluorinated biologically active molecules that are employed as pharmaceuticals or agrochemicals and in materials applications.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] Especially, copper(I) complexes are important as they enable the introduction of a broad variety of perfluoroalkyl groups into organic molecules that range from the simplest congener, trifluoromethyl, to longer linear and branched perfluoroalkyl groups such as the heptafluoroisopropyl (hfip) group.[7, 8, 9, 10] Although many of these complexes are used either in situ or immediately after generation, some complexes have been isolated and characterized, in detail. These complexes are often stabilized by co‐ligands that typically are pyridines or phosphanes, for example [(bpy)CuC2F5] (Figure 1)[11] and [(Ph3P)2Cu{CF(CF3)2}] ([(Ph3P)2Cu(hfip)]).[12] Silver(I) complexes have been employed as perfluoroalkylation reagents as well,[13, 14] although to a lesser extent than the related copper(I) derivatives. Because of their easy accessibility using silver(I) fluoride and the respective perfluoroalkene, for example, heptafluoropropene and tetrafluoroethylene,[15] they are of increasing interest. Similarly, copper(I) and silver(I) complexes with perfluorinated ligands that are coordinated via oxygen, sulfur, or selenium to the coinage metal have recently come into focus and have been established as transfer reagents for perfluorinated groups, for example for trifluoromethoxylation,[19, 20] trifluoromethylthiolation,[21, 22] and trifluoromethylselenolation reactions.[23, 24] So far, only few CuI and AgI metal complexes with the trifluoromethoxy ligand like [(PhtBu2P)(bpy)AgOCF3][25] are known (Figure 1).[25, 26, 27] The small number of structurally characterized complexes is due to the low stability of the OCF3 – ion that easily loses F– while releasing carbonyl fluoride (difluorophosgene), which enabled the use of AgOCF3 as C(O)F2 source.[28] This synthetic useful reaction is similar to the decomposition of perfluoroalkyl ions into perfluoroalkenes and fluoride, for example the generation of tetrafluoroethylene from the pentafluoroethyl ion.

Figure 1.

Top: Comparison of the availability of CuI and AgI complexes. Middle: Two‐step synthesis of salts of the N(CF3)2 − ion by electrochemical fluorination (ECF) of CF3SO2N(CH3)2.[16, 17] Bottom: Decomposition sequence of the N(CF3)2 − ion via perfluoroazapropene to give CF3N=CF−N(CF3)2.[18]

In contrast to perfluoroalkyl and perfluoroalkoxy groups, the chemistry of related perfluoroalkyl nitrogen substituents has been studied to a much lesser extent. Some synthetic strategies towards N‐trifluoromethylamines and related N‐perfluoroalkylnitrogen derivates have been developed in recent years.[28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38] Efficient strategies towards N,N‐bis(perfluoroalkyl)nitrogen compounds remain scarce, presumably, because of the lack of suitable starting materials.[18, 39, 40] Especially the N,N‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amino group is of interest as its organic derivatives are known to exhibit high stability, for example against acids and bases,[1, 41] and because its potential as substituent in pharmaceuticals was demonstrated, earlier.[42, 43] N,N‐Bis(trifluoromethyl)amino derivatives have been obtained from perfluoroazapropene CF3N=CF2 as initial starting compound or through tedious reaction sequences.[18, 39, 44] Perfluoroazapropene is only accessible through laborious multistep syntheses,[45, 46, 47] it is a reactive gas that requires special equipment for handling, and its transformation into the synthetically useful bis(trifluoromethyl)amide ion N(CF3)2 – is usually accompanied by dimerization giving CF3N=CF−N(CF3)2 (Figure 1). N,N‐Bis(trifluoromethyl)trifluoromethanesulfonimide CF3SO2N(CF3)2 is accessible through electrochemical fluorination (ECF) of CF3SO2N(CH3)2 in anhydrous hydrogen fluoride (aHF) according to the Simons process on a large scale.[16, 44, 48] CF3SO2N(CF3)2 reacts with fluorides such as silver(I) and rubidium fluoride providing a convenient access to the N(CF3)2 − ion (Figure 1).[17, 49] Some N,N‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amides with organic cations are stable whereas metal salts can only be handled in solution to prevent decomposition. Few of these organic salts have been used in metatheses[49, 50, 51, 52] or for the synthesis of organic molecules with the N(CF3)2 group.[39, 40, 53, 54] So far, mercury complexes, for example [Hg{N(CF3)2}2], are the sole stable metal complexes with the N(CF3)2 ligand, known.[55] The salts M{N(CF3)2} ⋅ NCCH3 (M=Ag, Cu) have been described as white solids.[49] However, these salts cannot be stored because they immediately start to decompose, even at low temperature.[56] So, they are no convenient, storable N(CF3)2 transfer reagents.

Herein, we present a set of stable and storable copper(I) and silver(I) complexes of the bis(trifluoromethyl)amido ligand. These complexes have been found to be promising compounds for the transfer of the bis(trifluoromethyl)amino group into organic molecules.

Copper(I) complexes with the N(CF3)2 ligand have been synthesized via metatheses using CH3CN solutions of rubidium or cesium bis(trifluoromethyl)amide that were generated from CF3SO2N(CF3)2 and the respective dry alkali metal fluoride (Figure 2). The dark orange complex [(bpy)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 a, bpy=2,2’‐bipyridine) was prepared from a solution of Rb{N(CF3)2} in acetonitrile and [Cu(bpy)2][CuCl2]. The copper(I) derivative [Cu(bpy)2][CuCl2] was either isolated and redissolved or prepared in situ from copper(I) chloride and 2,2’‐bipyridine giving almost equal yields for 1 a of 83 and 82 %, respectively. Alternatively, Cu{N(CF3)2} was synthesized from CuCl and Rb{N(CF3)2} in acetonitrile, and 2,2’‐bipyridine was added to give 1 a in 41 % yield (Figure 2). Because of the lower yield, all further copper(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes were synthesized from preformed copper(I) complexes and Rb{N(CF3)2} or Cs{N(CF3)2}. In addition to 1 a, the analogous dark orange 1,10‐phenanthroline (phen) complex [(phen)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 d) was isolated in 90 % yield. The colorless triphenylphosphane complex [(Ph3P)2Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 b) that was obtained in almost quantitative yield represents the third complex with a tricoordinate copper center. In contrast, the yellow‐orange mixed complexes [(bpy)(Ph3P)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 c) and [(phen)(Ph3P)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 e) that were isolated in 77 and 79 % yield, respectively, contain four coordinate CuI centers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Synthesis and crystal structures of the copper(I) complexes 1 a−1 e (thermal ellipsoids set at 25 % probability; H atoms are omitted for clarity; C atoms of the N‐ and P‐donor ligands are depicted as stick models).

Acetonitrile solutions of the silver(I) salt Ag{N(CF3)2} obtained from silver(I) fluoride and CF3SO2N(CF3)2 (Figure 1) were used for the synthesis of silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes (Figure 3). In analogy to the copper(I) N(CF3)2 derivatives, three‐ and four‐coordinate AgI complexes were obtained. The three colorless complexes [(bpy)Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 a), [(Ph3P)2Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 b), and [(bpy)(Ph3P)Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 c) were isolated in yields of 78, 89, and 90 %, respectively. The 2,2’:6’,2’’‐terpyridine (terpy) derivative [(terpy)Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 f) was obtained as a yellow crystalline material in 62 % yield.

Figure 3.

Synthesis and crystal structures of the silver(I) complexes 2 a−2 c, 2 f and of the complex silver(I) salt 3 (thermal ellipsoids set at 25 % probability; H atoms are omitted for clarity; C atoms of the N‐ and P‐donor ligands are depicted as stick models).

The silver(I) triphenylphosphane complex 2 b reacts with additional triphenylphosphane under formation of the complex salt [Ag(PPh3)4]{N(CF3)2} (3) that is composed of the tetrahedral [Ag(PPh3)4]+ cation and a non‐coordinated {N(CF3)2}– anion. Salt 3 was selectively prepared from triphenylphosphane and Ag{N(CF3)2} in 60 % yield and characterized, in detail (Figure 3). In contrast to [(Ph3P)2Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 b), the respective copper(I) complex [(Ph3P)2Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 b) does not react with an excess of triphenylphosphane to result in a complex salt and 1 b was obtained even in the presence of a twofold excess of PPh3 in 78 % yield.

The copper(I) and silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes are thermally stable with decomposition temperatures ranging from 114 to 204 °C (onset, DSC measurements). The solid complexes can be stored in a glove box in an inert atmosphere for more than one year without noticeable decomposition and they can be manipulated in air for a short period of time enabling a convenient handling.

The coordination of the bis(trifluoromethyl)amido ligand to copper in 1 a–1 e and to silver in 2 a–2 c and 2 f in the solid state is evident from single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction (SC‐XRD) analyses, which are the first examples for SC‐XRD studies on N(CF3)2 coordination compounds (Figures 2 and 3 and Table S5 in the Supporting Information). The metal‐nitrogen distances depend on the coordination number of the metal center. So, d(Cu−N(CF3)2) is 1.900(9)–2.004(8) Å in the tricoordinate complexes 1 a, 1 b, and 1 d but 2.0654(16) and 2.101(2) Å in four‐coordinate 1 c and 1 e, respectively. As expected from the slightly smaller covalent radius of copper (1.32 Å for Cu vs. 1.45 Å for Ag),[57] the metal−N(CF3)2 distance is longer in the silver(I) complexes with 2.138(2) and 2.255(4) Å for tricoordinate complexes 2 a and 2 b and 2.330(5) and 2.233(3) Å for the four‐coordinate derivatives 2 c and 2 f. The crystal structure of 3 proves the ionic nature of the complex salt (Figure 3). The N(CF3)2 – ion, which was until now not characterized by SC‐XRD, at all, is disordered over two positions precluding a detailed discussion of bonding parameters.

All copper(I) and silver(I) N(CF3)2 derivatives were characterized by multinuclear NMR, IR, and Raman spectroscopy, as well as by elemental analysis. The 19F NMR signal of the complexes is in the range from −40.7 to −43.7 ppm, which is similar to δ(19F) of Ag{N(CF3)2} and Cu{N(CF3)2} in CD3CN with −42.1 and −43.4 ppm, respectively. The signal of Rb{N(CF3)2} in CD3CN is observed at a significantly lower chemical shift of −37.5 ppm (Figure S17). Thus, the interaction between the coinage metal and the N(CF3)2 – ligand in solution is evident from the 19F NMR spectroscopic data. The signal of the complex salt [Ag(PPh3)4]{N(CF3)2} (3) in CD2Cl2 is observed at −39.6 ppm, which, in turn, is indicative for the ionic nature that was proven by the SC‐XRD study. Solid state 19F NMR spectra reveal an even more pronounced difference for δ iso(19F) with −31.6 and −34.6 ppm for the salt 3 and −40.4 and −41.4 ppm for the complexes [(Ph3P)2Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 b) and [(Ph3P)2Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 b) (Figure S19). The 31P and 13C solid state NMR spectra of 3 and 2 b also reveal the different bonding situations in the two related silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes. Especially, the smaller 1 J(107/109 Ag,31P) coupling constants observed for 3 are indicative for a four‐coordinate complex whereas larger 1 J(107/109 Ag,31P) hint towards a three‐coordinate silver complex in case of 2 b (Figure S18).[58]

The bis(triphenylphosphane) complexes 1 b and 2 b were studied by diffusion‐ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) in CD3CN and CD2Cl2 (Table S7). The diffusion constants derived from the 1H and 19F NMR measurements on samples dissolved in CD2Cl2 are very similar. The hydrodynamic radii of 1 b (1H DOSY: 6.15 Å; 19F DOSY: 5.97 Å) and 2 b (1H DOSY: 6.16 Å; 19F DOSY: 6.00 Å) calculated from diffusion constants using a modified Stokes‐Einstein equation, are close to radii estimated from the crystal structures (1 b: 5.07 Å; 2 b: 5.08 Å; see Supporting Information for a detailed description). Thus, it can be concluded that 1 b and 2 b remain intact in CD2Cl2. In contrast, in CD3CN the diffusion constants derived from the 1H NMR signals of the PPh3 ligands and from the 19F NMR signal of the N(CF3)2 − ligand are significantly different. However, the diffusion constant of the unbound N(CF3)2 − ion (D t(19F)=24.04 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1) derived from a DOSY study on 3 in CD3CN is much larger than D t(19F) measured for 1 b (17.48 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1) and 2 b (14.65 ⋅ 10−10 m2 s−1) in the same solvent. These data indicate an equilibrium between coordinated and free N(CF3)2 − in solutions of 1 b and 2 b in CD3CN as D t(19F) is an averaged value since M−N(CF3)2 bond formation and dissociation is too fast to be resolved on the NMR timescale. Similar to 1 b and 2 b, the bipyridine complexes 1 a and 2 a reveal partial dissociation into ions in CD3CN solution, as well.

The novel thermally robust bis(trifluoromethyl)amido copper(I) and silver(I) complexes were used for the introduction of the N(CF3)2 group into organic molecules. The reactions studied, so far, are i) nucleophilic substitutions giving a set of benzylbis(trifluoromethyl)amines (4−6), 2‐bis(trifluoromethyl)aminomethylnaphthalene (7), 2‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amino acetate (8 a), and ii) a Sandmeyer reaction leading to 1‐fluoro‐4‐bis(trifluoromethyl)aminobenzene (9).

The four benzylbis(trifluoromethyl)amines 4–6 and the naphthalene derivative 7 were isolated in yields of 56–65 % using the 2,2’‐bipyridine and 1,10‐phenanthroline complexes 1 a, 2 a, or 1 d as starting materials (Figure 4). The synthesis of the parent benzylbis(trifluoromethyl)amine 4 was reported using freshly prepared solutions of rubidium or cesium bis(trifluoromethyl)amide.[17, 59] Compounds 4 and 6 are liquids, whereas the para‐cyano derivative 5 and the naphthalene compound 7 are solids. The four related compounds 4–7 are air and water stable and no decomposition was observed during work‐up or storage. Crystals of 5 and 7 were studied by SC‐XRD. The N−CF3 distances in 5 (1.399(5) Å) and 7 (1.409(3) Å) are longer than in the coinage metal(I) complexes (ca. 1.35 Å).

Figure 4.

Synthesis of bis(trifluoromethyl)methyl arenes and crystal structures of 5 and 7.

The reaction of 2‐(bromomethyl)naphthalene with [(bpy)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 a) was screened in acetonitrile, dichloromethane, N,N‐dimethylacetamide (DMAC), toluene, pyridine, and THF. The highest yield for 7 was observed in CD3CN. In dichloromethane and DMAC significantly lower yields were obtained and in toluene, pyridine, and THF almost no conversion to 7 was observed by 19F NMR spectroscopy (Table S1).

2‐Bis(trifluoromethyl)amino acetate (8 a) was isolated in 56 % yield (Figure 5). Its conversion into ethyl N,N‐bis(trifluoromethyl)glycine (8 b) was described, earlier.[39] The synthesis of 8 b was repeated and the fluorinated amino acid was characterized by SC‐XRD for the first time. Two formula units of 8 b form dimers in the solid state via a cyclic H‐bond motif with d(O ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ O’)=2.679(3) Å that are located on a center of inversion (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Synthesis of 2‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amino acetate (8 a), its conversion into N,N‐bis(trifluoromethyl)glycine (8 b), and the crystal structure of 8 b (thermal ellipsoids set at 30 % probability; H atoms are omitted for clarity).

The conversion of ethyl bromoacetate into 8 a using different copper(I) and silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes was monitored by 19F NMR spectroscopy in CD3CN using benzotrifluoride as internal reference (Table 1). Especially, the complexes with 2,2’‐bipyridine and 1,10‐phenanthroline were found to be efficient N(CF3)2 transfer reagents and the copper(I) complexes 1 a and 1 d were identified as most efficient reagents with internal yields of 74 and 75 %, respectively. The related silver(I) complex 2 a gave ester 8 a in significantly lower yield of 54 %. Triphenylphosphane complexes are less efficient N(CF3)2 transfer reagents and the amount of 8 a formed, dropped with increasing number of PPh3 ligands at copper(I) or silver(I). The lower yields were accompanied with an increasing amount of side products. A major side product was identified as Ph3PF2 that was confirmed by 19F and 31P NMR spectroscopy in the reaction mixtures. Most of the phosphorane formed crystallized from the CD3CN solutions upon cooling to room temperature and a single crystal of Ph3PF2 was characterized by X‐ray diffraction (Figure S16).

Table 1.

Reactivity screening of copper(I) and silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes with ethyl bromoacetate to give 2‐bis(trifluoromethyl)amino acetate (8 a).[a]

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Complex |

|

Yield [%] |

|

1 |

[(bpy)Cu{N(CF3)2}] |

(1 a) |

75 |

|

2 |

[(phen)Cu{N(CF3)2}] |

(1 d) |

74 |

|

3 |

[(bpy)(Ph3P)Cu{N(CF3)2}] |

(1 c) |

33 |

|

4 |

[(phen)(Ph3P)Cu{N(CF3)2}] |

(1 e) |

39 |

|

5 |

[(Ph3P)2Cu{N(CF3)2}] |

(1 b) |

8 |

|

6 |

[(bpy)Ag{N(CF3)2}] |

(2 a) |

54 |

|

7 |

[(bpy)(Ph3P)Ag{N(CF3)2}] |

(2 c) |

28 |

|

8 |

[(Ph3P)2Ag{N(CF3)2}] |

(2 b) |

7 |

[a] The reactions were performed in Young NMR tubes and monitored by 19F NMR spectroscopy using equimolar amounts of the coinage metal(I) complex and ethyl bromoacetate. The internal yields were determined with benzotrifluoride as standard.

The lower yield of ester 8 a starting from [(bpy)Ag{N(CF3)2}] (2 a) compared to [(bpy)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 a; Table 1), tempted us to perform a comparative study on nucleophilic substitution reactions using complexes 1 a and 2 a (Table S2). Similar to the syntheses of 8 a, lower yields were observed for reactions using the silver(I) complex 2 a. The reactions studied include the synthesis of benzylbis(trifluoromethyl)amine 4 starting from benzylbromide and benzyliodide as well as the formation of 7 starting from the respective bromide. Furthermore, the conversion of allylbromide into allylbis(trifluoromethyl)amine (10) showed a much lower yield for (CF3)2NCH2CH=CH2 (10) in case of the reaction from 2 a (38 %) compared to 1 a (75 %).

The further potential of the coinage metal(I) complexes as bis(trifluoromethyl)amination reagents was demonstrated by the conversion of 4‐fluorobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate into 1‐fluoro‐4‐bis(trifluoromethyl)aminobenzene (9) with [(bpy)Cu{N(CF3)2}] (1 a) in 34 % yield as assessed by 19F NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 1). An analogous Sandmeyer reaction resulting in 9 was reported in the literature[40] starting from the corresponding 4‐fluorobenzenediazonium bis(trifluoromethyl)amide and a copper(I) salt with a yield of 43 %.[51] However, the preformation of the diazonium bis(trifluoromethyl)amide salt is inconvenient compared to a reaction with a stable and storable metal complex of the N(CF3)2 ligand. Furthermore, the addition of elemental copper was necessary to get any product. Preliminary results indicate a higher yield of 9 for the reaction of 4‐fluorobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate with 1 a, as well.

Scheme 1.

Sandmeyer‐type reaction of 1 d giving 9 (yield of 9 determined by 19F NMR spectroscopy with benzotrifluoride as internal standard).

The first copper(I) and silver(I) bis(trifluoromethyl)amido complexes using stabilizing N‐ and P‐donor ligands have been obtained in high yield starting from CF3SO2N(CF3)2, which is easily accessible by electrochemical fluorination (ECF). The complexes have unprecedented stabilities that allow for a long‐term storage and easy handling. This is a prerequisite for their application as bis(trifluoromethyl)amination reagents. The potential of these complexes, especially with pyridine‐type ligands, to serve as convenient N(CF3)2 transfer reagents was demonstrated by nucleophilic substitution reactions and a Sandmeyer reaction.

Experimental Section

Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction

Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction: Deposition Numbers 2051510‐2051523, 2052134 and 2055702 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

L. N. Schneider, E.-M. Tanzer Krauel, C. Deutsch, K. Urbahns, T. Bischof, K. A. M. Maibom, J. Landmann, F. Keppner, C. Kerpen, M. Hailmann, L. Zapf, T. Knuplez, R. Bertermann, N. V. Ignat'ev, M. Finze, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10973.

In memory of Siegfried Hünig.

Contributor Information

Leon N. Schneider, http://go.uniwue.de/finze‐group

Prof. Dr. Maik Finze, Email: maik.finze@uni-wuerzburg.de.

References

- 1.Kirsch P., Modern Fluororganic Chemistry, 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y., Wang J., Gu Z., Wang S., Zhu W., Aceña J. L., Soloshonok V. A., Izawa K., Liu H., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 422–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meanwell N. A., J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5822–5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., Sánchez-Roselló, Aceña J. L., del Pozo C., Sorochinsky A. E., Fustero S., Soloshonok V. A., Liu H., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller K., Faeh C., Diederich F., Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso C., de Marigorta E. M., Rubiales G., Palacios F., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1847–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomashenko O. A., Grushin V. V., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4475–4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen P., Liu G., Synthesis 2013, 45, 2919–2939. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lantaño B., Torviso M. R., Bonesi S. M., Barata-Vallejo S., Postigo A., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 285, 76–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Shi X., Li X., Shi D., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 2213–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panferova L. I., Miloserdov F. M., Lishchynskyi A., Martínez Belmonte M., Benet-Buchholz J., Grushin V. V., Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 5307–5311; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5218–5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrella N. O., Liu K.-G., Gabidullin B., Vasiliu M., Dixon D. A., Baker R. T., Organometallics 2018, 37, 422–432. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafner A., Jung N., Bräse S., Synthesis 2014, 46, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyrra W., Naumann D., J. Fluorine Chem. 2004, 125, 823–830. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller T. W., Burnard R. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 7367–7368. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sartori P., Ignat'ev N., Datsenko S., J. Fluorine Chem. 1995, 75, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- 17.V. Hilarius, H. Buchholz, P. Sartori, N. Ignatiev, A. Kucherina, S. Datsenko (Merck Patent GmbH), WO2000046180, 2000.

- 18.Ang H. G., Syn Y. C., Adv. Inorg. Chem. Radiochem. 1974, 16, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tlili A., Toulgoat F., Billard T., Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 11900–11909; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11726–11735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X., Tang P., Sci. China Chem. 2019, 62, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X.-H., Matsuzaki K., Shibata N., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 731–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toulgoat F., Alazet S., Billard T., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tlili A., Ismalaj E., Glenadel Q., Ghiazza C., Billard T., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3659–3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghiazza C., Tlili A., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D., Lu L., Shen Q., Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang C.-P., Vicic D. A., Organometallics 2012, 31, 7812–7815. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen S., Huang Y., Fang X., Li H., Zhang Z., Hor T. S. A., Weng Z., Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 19682–19686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turksoy A., Scattolin T., Bouyad-Gervais S., Schoenebeck F., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 2183–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scattolin T., Deckers K., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 227–230; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scattolin T., Bouayad-Gervais S., Schoenebeck F., Nature (London) 2019, 573, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onida K., Vanoye L., Tlili A., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 6106–6109. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blastik Z. E., Voltrová S., Matoušek V., Jurásek B., Manley D. W., Klepetářová B., Beier P., Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 352–355; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niedermann K., Früh N., Senn R., Czarniecki B., Verel R., Togni A., Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 6617–6621; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6511–6515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang S., Wei J., Jiang L., Liu J., Mumtaz Y., Yi W., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8536–8539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milcent T., Crousse B., C. R. Chimie 2018, 21, 771–781. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu J., Lin J.-H., Xiao J.-C., Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 16896–16900; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16669–16673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thota N., Makam P., Rajbongshi K. K., Nagiah S., Abdul N. S., Chuturgoon A. A., Kaushik A., Lamichhane G., Somboro A. M., Kruger H. G., Govender T., Naicker T., Arvidsson P. I., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 1457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Z., van der Werf A., Deliaval M., Selander N., Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 2791–2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breitenstein C., Ignat'ev N., Frank W., J. Fluorine Chem. 2018, 210, 166–177. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirschberg M. E., Ignat'ev N. V., Wenda A., Frohn H.-J., Willner H., J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 135, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 41.L. M. Yagupol'skii, Aromatic and Heterocyclic Compounds with Fluoro-containing Substituents, Naukova Dumka, Kiev, 1988.

- 42.Yagupol'skii L. M., Shavaran S. S., Klebanov B. M., Rechitskii A. N., Maletina I. I., Pharm. Chem. J. 1994, 28, 813–817. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haszeldine R. N., Tipping A. E., Valentine R. H., J. Fluorine Chem. 1982, 21, 329–334. [Google Scholar]

- 44.N. Ignat′ev in Modern Synthesis Processes and Reactivity of Fluorinated Compounds (Eds.: H. Groult, F. Leroux, A. Tressaud), Elsevier, London, 2016.

- 45.Fawcett F. S., Tullock C. W., Coffman D. D., J. Chem. Eng. Data 1965, 10, 398–399. [Google Scholar]

- 46.E. Klauke, H. Holtschmidt, K. Findeisen (Farbenfabriken Bayer AG), DE2101107, 1972.

- 47.Nishida M., Fukaya H., Hayashi E., Abe T., J. Fluorine Chem. 1999, 95, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ignat′ev N., Sartori P., J. Fluorine Chem. 2000, 101, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 49.U. Heider, M. Schmidt, P. Sartori, N. Ignatyev, A. Kucherina, L. Zinovyeva (Merck Patent GmbH), WO2002064542, 2002.

- 50.Hirschberg M. E., Wenda A., Frohn H.-J., Ignat'ev N. V., J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 138, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirschberg M. E., Ignat'ev N. V., Wenda A., Frohn H.-J., Willner H., J. Fluorine Chem. 2012, 135, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 52.U. Heider, M. Schmidt, P. Sartori, N. Ignatyev, A. Kucheryna (Merck Patent GmbH), EP1081129, 2001.

- 53.W. Hierse, N. Ignatyev, M. Seidel, E. Montenegro, P. Kirsch, A. Bathe (Merck Patent GmbH), WO2008003447, 2008.

- 54.Frömel T., Peschka M., Fichtner N., Hierse W., Ignatiev N. V., Bauer K.-H., Knepper T. P., Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 22, 3957–3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young J. A., Tsoukalas S. N., Dresdner R. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 3604–3606. [Google Scholar]

- 56.L. N. Schneider, K. Maibom, C. Deutsch, N. V. Ignat′ev, M. Finze, unpublished results.

- 57.Cordero B., Gomez V., Platero-Prats A. E., Reves M., Echeverria J., Cremades E., Barragan F., Alvarez S., Dalton Trans. 2008, 2832–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.S. Berger, S. Braun, H.-O. Kalinowski, NMR Spectroscopy of the Non-Metallic Elements, Wiley, Chichester, 1997.

- 59.Vinogradov A. S., Gontar A. F., Knunyants I. L., Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Khim. 1980, 7, 1683–1684. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information