Abstract

Aim

To compare the efficacy and safety of LY2963016 insulin glargine (LY IGlar) with insulin glargine (Lantus; IGlar) combined with oral antihyperglycaemic medications (OAMs) in insulin‐naive Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Materials and Methods

In this phase III, open‐label trial, adult patients with T2D receiving two or more OAMs at stable doses for 12 weeks or longer, with HbA1c of 7.0% or more and 11.0% or less, were randomized (2:1) to receive once‐daily LY IGlar or IGlar for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was non‐inferiority of LY IGlar to IGlar at a 0.4% margin, and a gated secondary endpoint tested non‐inferiority of IGlar to LY IGlar (−0.4% margin), assessed by least squares (LS) mean change in HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks.

Results

Patients assigned to LY IGlar (n = 359) and IGlar (n = 177) achieved similar and significant reductions (p < .001) in HbA1c from baseline. LY IGlar was non‐inferior to IGlar for change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 (−1.27% vs. −1.23%; LS mean difference: −0.05% [95% CI, −0.19% to 0.10%]) and IGlar was non‐inferior to LY IGlar. The study therefore showed equivalence of LY IGlar and IGlar for the primary endpoint. At week 24, there were no between‐group differences in the proportion of patients achieving an HbA1c of less than 7.0%, seven‐point self‐measured blood glucose, insulin dose or weight gain. Adverse events, allergic reactions, hypoglycaemia and insulin antibodies were similar in the two groups.

Conclusions

Once‐daily LY IGlar and IGlar, combined with OAMs, provide effective and similar glycaemic control with comparable safety profiles in insulin‐naive Chinese patients with T2D.

Keywords: insulin glargine, non‐inferiority, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a progressive disease characterized by deterioration and eventual loss of pancreatic β‐cell function, resulting in inadequate production of insulin and chronic hyperglycaemia.1, 2 The International Diabetes Federation estimated that the number of people worldwide with diabetes in 2019 was 463 million, of which China accounted for 116.4 million, ranking first.2 The latest epidemiological survey of Chinese adults showed that the standardized prevalence of total diabetes and prediabetes using the American Diabetes Association criteria was 12.8% and 35.2%, respectively.3

Exogenous insulin is considered the most effective treatment for lowering high blood glucose if adequate glycaemic control cannot be achieved through combinations of diet, exercise and oral antihyperglycaemic medications (OAMs).4, 5, 6, 7 Long‐acting basal insulin analogues were developed to more closely match the kinetics of endogenous insulin compared with conventional intermediate‐acting basal insulins such as human neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH). Insulin glargine (IGlar; Lantus) was the first long‐acting insulin analogue to be approved for use in patients with T2D, in 2000.8, 9 IGlar is associated with similar effectiveness for glycaemic control as NPH but with a moderate reduction in incidence of hypoglycaemia, and allows once‐daily injection versus two or more daily injections for NPH.8, 9

LY2963016 insulin glargine (LY IGlar; Abasaglar [European Union]; Basaglar [United States]) is a long‐acting human insulin analogue with an identical amino acid sequence, pharmaceutical form and strength (concentration of the active ingredient) as IGlar.10 LY IGlar was the first biosimilar insulin to receive approval from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in September 2014.11 ‘Biosimilar’ is a regulatory designation with different definitions under different jurisdictions. The EMA defines a biosimilar as ‘a biological medicinal product that contains a version of the active substance of an already authorized original biological medicinal product (reference medicinal product)’.12 Similarity must be established in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety and efficacy.13, 14 The China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) requires independent approval of biosimilar medications, using criteria closely aligned with the EMA regulations.15

In line with regulatory guidance and scientific requirements for showing biosimilarity, LY IGlar has been shown to have similar pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and clinical properties to IGlar.10 Two phase III trials, ELEMENT 216 and ELEMENT 5,17 showed equivalent efficacy and similar safety profiles for LY IGlar and IGlar when used in combination with OAMs in insulin‐naive or insulin‐experienced patients with T2D, and the ELEMENT 1 trial showed the equivalence of LY IGlar and IGlar in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D).16, 17, 18 Although the ELEMENT 5 and ELEMENT 2 study populations included 47.5% and 8.5% Asian patients, respectively,16, 17, 19 the equivalence of LY IGlar and IGlar has not been investigated in a Chinese population. In addition, the China NMPA requires data from one phase I and two phase III studies (in T1D and T2D) to establish similarity with the reference product (IGar).15

In this study, we report the results of a phase III trial that compared the efficacy and safety of LY IGlar with IGlar in combination with OAMs in insulin‐naive Chinese patients with T2D inadequately controlled with two or more OAMs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

A phase III, randomized, parallel‐arm, open‐label, non‐inferiority study was conducted at multiple study centres in China. The study comprised a 24‐week treatment period (a 12‐week titration period and a 12‐week maintenance period) and a 4‐week post‐treatment follow‐up (Figure S1). The primary objective of the study was to determine non‐inferiority of once‐daily LY IGlar versus IGlar by a margin of 0.4%, as measured by change in HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks, when used in combination with OAMs. The study was conducted following the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and local applicable laws and regulations.20 Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients before inclusion in the study. The study protocol was approved by Ethics Review Boards at each participating institution (Supplementary Appendix) and was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on 9 November 2017 (NCT03338010). A full list of study investigators is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

2.2. Patients

This study enrolled adults (aged ≥18 years) with a diagnosis of T2D based on the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria who were insulin‐naive and received two or more OAMs at stable doses for at least 12 weeks prior to screening, with HbA1c of 7.0% or more and 11.0% or less, and a body mass index (BMI) of 35 kg/m2 or less. Key exclusion criteria included use of insulin therapy in the past year (except for use during pregnancy or for short‐term management of acute conditions for a maximum of 4 continuous weeks), use of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists within 90 days before screening, use of traditional medicines with known/specified antihyperglycaemic effects within 3 months before screening, more than one episode of severe hypoglycaemia or two or more emergency room visits or hospitalizations because of poor glucose control within 6 months prior to screening and known hypersensitivity or allergy to IGlar or its excipients.

2.3. Randomization and treatment

Eligible patients were randomized using an interactive web response system in a 2:1 ratio to receive LY IGlar or IGlar once daily for 24 weeks at a starting dose of 10 U/day and a fixed dose of OAMs. Randomization was stratified by HbA1c stratum (<8.5%, ≥8.5%) and entry use of insulin secretagogues (sulphonylurea [SU], meglitinide or neither). Both LY IGlar and IGlar were provided to study patients as a 100 U/mL solution for injection in a prefilled pen injector and insulin was self‐administered by the patients from the day after randomization. Following initiation of basal insulin, the insulin dose was titrated under supervision of the investigators using a weekly dosing algorithm (Table S1) to achieve fasting blood glucose (FBG) of 100 mg/dL or less (≤5.6 mmol/L) while avoiding hypoglycaemia. It was expected that dose titration would be completed during the titration period (weeks 0–12), with any further adjustments made after week 12 mainly for safety concerns such as hypoglycaemia or unacceptable hyperglycaemia.

2.4. Endpoints and measurements

The primary study endpoint was change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24. Secondary endpoints included change in HbA1c from baseline to weeks 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20, and the percentage of patients with HbA1c of less than 7% or 6.5% or less, seven‐point self‐measured blood glucose (SMBG; premeal for each meal; postmeal for each meal and bedtime), intrapatient variability of seven‐point SMBG values measured by the standard deviation (SD), basal insulin dose (U/day and U/kg/day), and weight change.

Clinic visits occurred at screening, randomization (week 0), at weeks 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24, and at a safety follow‐up. HbA1c analyses were performed by a central laboratory (Covance, Shanghai, China) using the Variant II Haemoglobin A1c high‐performance liquid chromatography testing system (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Seven‐point SMBG readings were collected on two separate days in the 2 weeks before baseline, at clinical visits on weeks 2, 6, 12 and 24, and were measured using glucometers provided as part of the study (ACCU‐CHEK Performa; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). Study personnel trained patients on how to monitor their own blood glucose levels, and proper use of the study diary for recording blood glucose values and corresponding insulin doses, hypoglycaemic episodes and adverse events (AEs). Immunogenicity was assessed at baseline, at weeks 2, 4 and 12, and at the 24‐week endpoint at a central laboratory (WuXi AppTec Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) using a proprietary validated radioligand binding assay designed to detect anti‐IGlar antibodies in the presence of the investigational product. The anti‐LY IGlar antibody assay has cross‐reactivity to IGlar and human insulin, and the same assay was used to detect antibodies to IGlar. Treatment‐emergent antibody response (TEAR) was based on change in anti‐insulin antibody level (% binding) from baseline.

Treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs), defined as events that were reported as new or worsening in severity after the first study treatment following randomization, were documented at every visit and coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 22.1. Hypoglycaemia was defined as an event associated with signs or symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia or a blood glucose level of 70 mg/dL or less (≤3.9 mmol/L), even if not associated with signs or symptoms. Nocturnal hypoglycaemia was defined as any hypoglycaemic event that occurred between bedtime and waking, and severe hypoglycaemia was defined as a hypoglycaemic event requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer treatment or other resuscitative actions.

Other safety assessments included special topic assessment of allergic reactions and injection site AEs. Injection site AEs were evaluated for pain, pruritus and rash associated with the injection, as well as the characteristics of the injection site (abscess, nodule, lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy or induration). Allergic or immunological conditions were assessed by determining the frequency and severity of AEs from a prespecified list of AE terms.

2.5. Statistics

To show non‐inferiority of LY IGlar to IGlar for change in HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks with a 0.4% non‐inferiority margin (NIM) with a 2:1 allocation ratio and assuming no treatment difference, a common SD of 1.3%, two‐sided alpha of .05, more than 85% power and a 15% dropout rate at 24 weeks, the enrolment target was set at 530 patients (LY IGlar, n = 353 and IGlar, n = 177). The NIM was selected based on United States Food and Drug Administration guidance for diabetes bioequivalence trials, which also fulfils the requirements of the China NMPA.21

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) and were based on a full analysis set (FAS) population, defined as all patients who were randomized and received one or more doses of study medication. Efficacy analyses were conducted in patients with both non‐missing baseline values and one or more non‐missing postbaseline values. Two‐sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were included in the presentation of the results.

The primary analysis of change in HbA1c level from baseline to week 24 was conducted using a likelihood‐based, mixed model repeated measure (MMRM) approach, treating the data as missing at random (MAR) in the FAS. The MMRM model evaluated the change from baseline HbA1c as the dependent variable with treatment assignment, entry use of insulin secretagogues (SU, meglitinide, neither), visit, and interaction between visit and treatment as fixed effects, baseline HbA1c as a covariate and a random effect for patient. The primary treatment comparison was least squares (LS) mean change in HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks for LY IGlar versus IGlar using an NIM of 0.4%. If the +0.4% NIM was met, then a gated secondary comparison of IGlar versus LY IGlar at a NIM of −0.4% was conducted; if the lower limit of the 95% CI for the difference in LS mean change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 for IGlar versus LY IGlar was more than −0.4% then IGlar was declared non‐inferior to LY IGlar. In this case, LY IGlar was therefore considered to have equivalent efficacy to IGlar. This gate‐keeping procedure controlled the family‐wise type 1 error rate at a one‐sided .025 level.

Analysis of continuous secondary efficacy and safety measurements used the same MMRM model as the primary efficacy analyses with the baseline response variable added as a covariate in the FAS population. Continuous laboratory measures were analysed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. For categorical measures, Fisher's exact test was used.

A subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate change in HbA1c and body weight from baseline to week 24 using a MMRM for the following subgroups: baseline HbA1c level (< or ≥8.5%), use of insulin secretagogues (SU, meglitinide, neither), BMI (< or ≥28 and 24 kg/m2), age (< or ≥65 years), sex and kidney function assessed by estimated glomerular filtration rate (normal or increased [≥90 mL/min/1.73m2], mild reduction [60–89 mL/min/1.73m2] and moderate reduction [30–59 mL/min/1.73m2]).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

A total of 696 patients were screened, of whom 536 were randomized and received one or more doses of study treatment (FAS population: LY IGlar, n = 359; IGlar, n = 177). In total, 93.6% (n = 336) of patients in the LY IGlar group and 89.8% (n = 159) in the IGlar group completed the study. The most common reason for study discontinuation in both groups was ‘withdrawal by patient’ (LY IGlar, n = 14; IGlar, n = 8) (Figure S2).

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics were well balanced between the treatment groups (Table 1). The majority of patients (71.5%) were receiving SUs and 67.0% were receiving two OAMs before randomization. The most common combination of two OAMs was metformin and SU (33.8% of total patients [n = 181]), followed by alpha glucosidase inhibitors and metformin (11.4% of total patients [n = 61]) (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Variablea | LY IGlar (n = 359) | IGlar (n = 177) | Total (N = 536) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.3 (9.6) | 59.5 (8.9) | 58.7 (9.4) |

| Median (range) | 59.0 (27–83) | 60.0 (30–80) | 59.0 (27–83) |

| ≥65, n (%) | 95 (26.5) | 58 (32.8) | 153 (28.5) |

| Males, n (%) | 209 (58.2) | 98 (55.4) | 307 (57.3) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 359 (100) | 177 (100) | 536 (100) |

| Body weight, kg | 69.10 (11.58) | 68.35 (11.72) | 68.86 (11.62) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 25.363 (2.988) | 25.411 (3.378) | 25.379 (3.119) |

| HbA1c | |||

| % | 8.42 (1.04) | 8.39 (0.92) | 8.41 (1.00) |

| mmol/mol | 68.6 (11.4) | 68.2 (10.1) | 68.4 (11.0) |

| HbA1c at baseline, n (%) | |||

| <8.5% (<69 mmol/mol) | 204 (56.8) | 100 (56.5) | 304 (56.7) |

| ≥8.5% (≥69 mmol/mol) | 155 (43.2) | 77 (43.5) | 232 (43.3) |

| FBG at baselineb | |||

| mg/dL | 169.0 (39.17) | 163.1 (39.04) | 167.0 (39.19) |

| mmol/L | 9.38 (2.174) | 9.05 (2.167) | 9.27 (2.175) |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 10.09 (5.47) | 10.69 (5.94) | 10.29 (5.63) |

| Number of OAMs before randomization, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 233 (64.9) | 126 (71.2) | 359 (67.0) |

| 3 | 118 (32.9) | 46 (26.0) | 164 (30.6) |

| 4 | 8 (2.2) | 5 (2.8) | 13 (2.4) |

| Entry use of insulin secretagogues, n (%) | |||

| Sulphonylureas | 254 (70.8) | 129 (72.9) | 383 (71.5) |

| Meglitinide | 27 (7.5) | 12 (6.8) | 39 (7.3) |

| Neither | 78 (21.7) | 36 (20.3) | 114 (21.3) |

Abbreviations: FBG, fasting blood glucose; IGlar, insulin glargine; LY IGlar, LY2963016 insulin glargine; OAM, oral antihyperglycaemic medication.

Variables are summarized as mean (standard deviation) unless stated.

By self‐monitored blood glucose.

3.2. Efficacy

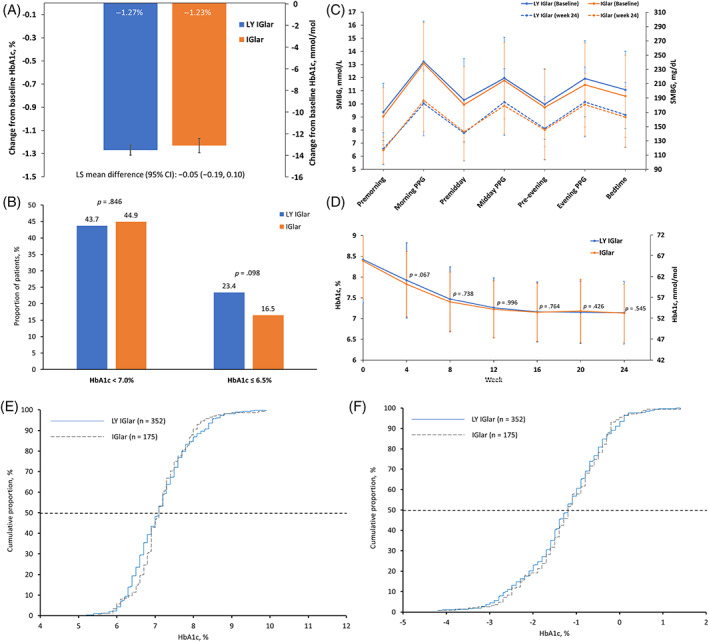

A significant reduction in mean HbA1c level was observed in both treatment groups between baseline and weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 (p < .001 for all time points), and the LS mean change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 was −1.27% and − 1.23% for the LY IGlar and IGlar groups, respectively (Figure 1A,D). The primary study endpoint was met, with a LS mean difference for reduction in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 between the LY IGlar and IGlar groups of −0.05% (95% CI; −0.19%, 0.10%), which was within the predefined NIM of 0.4% (Figure 1A, Table 2). Non‐inferiority of IGlar to LY IGlar was also shown in the gated secondary treatment comparison, as the lower bound of the 95% CI was within −0.4% (Table 2). These two non‐inferiority results showed equivalent efficacy of LY IGlar and IGlar for reduction of HbA1c from baseline to week 24. Furthermore, at week 24, a similar proportion of patients in the LY IGlar and IGlar groups had achieved HbA1c of less than 7.0% (43.7% vs. 44.9%, p = .846) and 6.5% or less (23.4% vs. 16.5%, p = .098) (Figure 1B, Table 2). Estimated cumulative frequency distributions of HbA1c at week 24 and change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 are shown in Figure 1E,F.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of study endpoints. A, Change in least squares mean HbA1c from baseline to week 24; B, the proportion of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.0% and ≤6.5% at week 24; C, mean seven‐point self‐monitored blood glucose at baseline and week 24; D, changes in HbA1c for time points from baseline to week 24 (p‐values are for between‐group differences); E, cumulative distribution of HbA1c at week 24; and F, cumulative distribution of change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24. Error bars represent standard deviation; horizontal dashed lines represent the 50th percentile. IGlar, insulin glargine; LS, least squares; LY IGlar, LY2963016 insulin glargine; PPG, postprandial glucose; SMBG, self‐measured blood glucose

TABLE 2.

Summary of clinical assessments at week 24 (FAS)

| Measurementa | LY IGlar (n = 359) | IGlar (n = 177) |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c, % | ||

| Week 24 | 7.13 (0.043) | 7.18 (0.062) |

| Change from baseline to week 24 | −1.27 (0.043) | −1.23 (0.062) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI) | −0.05 (−0.19, 0.10) | |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | ||

| Week 24 | 54.5 (0.47) | 55.0 (0.67) |

| Change from baseline to week 24 | −13.9 (0.47) | −13.4(0.67) |

| LS mean difference (95% CI) | −0.5 (−2.11, 1.11) | |

| HbA1c target values, n (%) | ||

| <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) | 146 (43.7) | 71 (44.9) |

| ≤6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol) | 78 (23.4) | 26 (16.5) |

| FBG change from baselineb | ||

| mmol/L | −2.70 (0.061) | −2.76 (0.088) |

| mg/dL | −48.7 (1.09) | −49.7 (1.59) |

| Insulin dose | ||

| U/day | 16.0 (0.43) | 15.7 (0.61) |

| U/kg/day | 0.23 (0.006) | 0.22 (0.008) |

| Weight change from baseline, kg | 1.1 (0.13) | 1.2 (0.19) |

| Hypoglycaemia, n (%) [no. of events] | ||

| Total (≤70 mg/dL) | 180 (50.1) [581] | 96 (54.2) [295] |

| Total (<54 mg/dL) | 22 (6.1) [29] | 10 (5.7) [14] |

| Nocturnal | 53 (14.8) [101] | 25 (14.1) [40] |

| Severe | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoglycaemia rate overall,c mean (SD) | ||

| Total (≤70 mg/dL) | 3.96 (10.76) | 3.87 (7.39) |

| Total (<54 mg/dL) | 0.20 (1.00) | 0.19 (0.85) |

| Nocturnal | 0.76 (3.74) | 0.53 (1.61) |

| Severe | 0 | 0 |

| Detectable insulin antibodies, n (%) | 69 (19.3) | 31 (17.5) |

| Cross‐reactive insulin antibodies, n (%) | 53 (14.8) | 24 (13.6) |

| TEAR, n (%) | 61 (17.1) | 29 (16.4) |

All measurements are least squares mean (standard error) unless specified.

By self‐measured blood glucose.

Events/patient/year, the overall rate at week 24 accounts for all events reported during the 24‐week treatment period.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; FBG, fasting blood glucose; IGlar, insulin glargine; LY IGlar, LY2963016 insulin glargine; LS, least squares; TEAR, treatment‐emergent antibody response.

p > .05 for all treatment group comparisons.

A graphical summary of mean seven‐point SMBG values at baseline and week 24 for both treatment groups is shown in Figure 1C. Improvements in SMBG at all seven time points were observed between baseline and week 24 for both treatment groups and no statistically significant treatment differences were observed between groups. In addition, there were no differences in the SDs of mean seven‐point SMBG values between the LY IGlar and IGlar treatment groups at week 24, showing comparable variability between the two groups. Patients in the LY IGlar and IGlar groups also achieved a similar reduction in FBG from baseline to week 24 (Table 2).

At week 24, the mean daily insulin dose was comparable between the two treatment groups (Table 2). Patients in both groups experienced around a 1 kg increase in body weight between baseline and week 24, with no statistically significant difference (Table 2).

A subgroup analysis found no significant treatment‐by‐subgroup interactions for change in HbA1c or bodyweight from baseline to week 24 (p > .05 for all subgroups; Tables S2 and S3).

3.3. Safety

After 24 weeks, there were no significant differences in the cumulative incidences of total hypoglycaemia (LY IGlar: 50.1%; IGlar: 54.2%; p = .418) or nocturnal hypoglycaemia (LY IGlar 14.8%; IGlar 14.1%; p = .836) between the treatment groups, and no severe hypoglycaemic events were reported in either group (Table 2). In addition, there were no significant differences in rates of hypoglycaemia adjusted for 1 year (total, nocturnal and severe) between the treatment groups (Table 2).

TEAEs and serious AEs (SAEs) were reported by a similar proportion of patients in the LY IGlar and IGlar treatment groups, with less than 1% of SAEs considered possibly related to treatment (Table 3). No deaths were reported during the study. The most common TEAEs (occurring in ≥5% of patients) in both treatment groups were upper respiratory tract infection (20.3% [n = 73] vs. 18.1% [n = 32]), hypertension (5.6% [n = 20] vs. 4.5% [n = 8]) and weight increase (3.9% [n = 14] vs. 6.2% [n = 11]). SAEs considered related to study treatment were rare and occurred in three patients receiving LY IGlar and one receiving IGlar.

TABLE 3.

Safety summary

| AEsa | LY IGlar (n = 359) | IGlar (n = 177) |

|---|---|---|

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinuation from treatment because of AEs, n (%) | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Patients experiencing ≥1 TEAE, n (%) | 233 (64.9) | 105 (59.3) |

| Possibly related to study treatment | 58 (16.2) | 21 (11.9) |

| Patients experiencing ≥1 serious AE, n (%) | 28 (7.8) | 14 (7.9) |

| Possibly related to study treatment | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) |

| Special topic assessment of allergic reactions, n (%) | 31 (8.6) | 10 (5.6) |

| Periarthritis, joint effusion, arthralgia, arthritis | 10 (2.8) | 4 (2.3) |

| Pruritus, rash, urticaria, dermatitis, dermatitis allergic | 9 (2.5) | 4 (2.3) |

| Injection site (pruritus, rash, induration, nodule) | 10 (2.8) | 1 (0.6) |

| Otherb | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) |

| Injection site reactions, n (%)c | 20 (5.6) | 5 (2.8) |

| Pain | 15 (4.2) | 5 (2.8) |

| Pruritus | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Rash | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Induration | 3 (0.8) | 0 |

| Nodule | 3 (0.8) | 0 |

| Ecchymosis | 1 (0.3) | 0 |

Patients may be counted in >1 category.

Hypersensitivity, asthma, eyelid oedema, gingival swelling.

p > .1.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; IGlar, insulin glargine; LY IGlar, LY2963016 insulin glargine; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

p > .1 for all comparisons, except for special topic assessment of allergic reactions, for which p‐values were unevaluable because of small patient number.

The incidence of injection site reactions was similar between the two treatment groups, with injection site pain the most commonly reported reaction (Table 3). In addition, a total of 100 patients (18.7%) had detectable anti‐insulin antibodies and 77 patients (14.4%) had cross‐reactive antibodies to insulin, but there were no statistically significant treatment differences (LY IGlar; 19.3% and 14.8% vs. IGlar; 17.5% and 13.6%) (Table 2). In addition, the proportion of patients with detectable anti‐insulin antibodies showed no significant treatment differences at all time points (Figure S3). Furthermore, TEARs were detected in a comparable proportion of patients in each treatment group (17.1% vs. 16.4%).

4. DISCUSSION

This study met its primary endpoint, showing that LY IGlar is non‐inferior to IGlar for reduction of HbA1c from baseline to week 24 when combined with OAMs in insulin‐naive Chinese patients with T2D at a NIM of 0.4%, meeting China NMPA regulatory requirements.15 Conversely, a prespecified gated secondary analysis showed that IGlar is non‐inferior to LY IGlar. Thus, these results show that LY IGlar and IGlar have equivalent efficacy in this patient population. In addition, analysis of secondary endpoints at week 24 further supports the similar efficacy of LY IGlar and IGlar, with comparable and significant within‐group reductions in HbA1c, and a comparable proportion of patients in each group achieving HbA1c of less than 7.0% or 6.5% or less. The current study also showed that LY IGlar was well tolerated and has a similar safety profile and potential for immunogenicity as IGlar. Treatment‐related TEAEs, injection site reactions and detectable anti‐insulin antibodies were reported in a similar proportion of patients in both treatment groups. There were also no statistically significant treatment differences for the incidence or rate of any category of hypoglycaemia.

Two previous phase III clinical trials compared LY IGlar and IGlar in combination with OAMs in patients with T2D: ELEMENT 2 and ELEMENT 5.16, 17 In contrast to the current study, these previous studies included both basal insulin‐naive and insulin‐experienced patients (IGlar in ELEMENT 2 and IGlar, NPH insulin or insulin detemir in ELEMENT 5). In addition, ELEMENT 2 was conducted in the United States, and ELEMENT 5 included predominantly Asian (48%) or White (46%) patients. It should be noted that there are recognized differences between Asian and Western T2D populations including lower BMI at onset of diabetes for Asian patients.22 As expected, the mean BMI of Chinese patients receiving LY IGlar and IGlar in the current study (25.363 [2.988] and 25.411 [3.378] kg/m2) was lower than the Western patients in the ELEMENT 2 study (32.0 [6.0] and 32.0 [5.0] kg/m2, respectively).16 Despite these differences in patient populations, the reductions in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 reported for patients assigned to LY IGlar and IGlar in ELEMENT 2 (−1.29% vs. −1.34%) and ELEMENT 5 (−1.25% vs. −1.22%) were closely aligned with the results of the current study (−1.27% vs. −1.23%).16, 17 Furthermore, a subgroup analysis of the East Asian patients included in the ELEMENT 5 study (n = 134) also reported similar reductions in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 to those observed in the current study (LY IGlar: −1.28%; IGlar: −1.26%).19 Taken together, these findings show that LY IGlar and IGlar have similar antihyperglycaemic efficacy in patients with T2D from a broad range of racial groups and in a wide range of geographical settings.

The safety profile observed for LY IGlar in this study was similar to IGlar, and the most common TEAEs (upper respiratory tract infection, hypertension and weight increase) were consistent with the findings of ELEMENT 2 and 5, ELEMENT 1 (in patients with T1D) and the original clinical trials of IGlar.16, 17, 18, 23 A numerically higher rate of injection site reactions was observed for patients receiving LY IGlar versus IGlar (5.6% vs. 2.8%); however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p > .1) and all events were mild in severity, with none leading to treatment discontinuation. Furthermore, the injection site reaction category with the greatest difference between the LY IGlar and IGlar groups was ‘pain’ (4.2% vs. 2.8%), which is a subjective measurement. No differences in the overall incidence or rate of total hypoglycaemia were observed between patients receiving LY IGlar and IGlar (50.1% vs. 54.2% and 3.96 vs. 3.87 events/patient/year, respectively). It is interesting to note that the rates of total hypoglycaemia in the current study were lower than those reported in the phase III ELEMENT 2 and 5 studies (17.0–23.4 events/patient/year).17, 18 The most probable explanation for this is that the Chinese patients in the current study received a lower dose of insulin at week 24 (LY IGlar: 0.23; IGlar: 0.22 U/day) compared with patients in ELEMENT 2 and 5 (0.48–0.61 U/day).16, 17 This may reflect that Chinese doctors and patients are generally very cautious about insulin dose titration, which is also reflective of the differences in BMI and insulin dose requirements between Chinese and Caucasian populations.22 Finally, the proportion of patients in the current study with detectable anti‐IGlar antibodies in the LY IGlar and IGlar groups after 24 weeks of treatment (19.3% and 17.5%, respectively) were within the range reported by the previous ELEMENT studies (11%–34%).16, 17, 18, 19

This study has several key strengths. First, it represents the first large‐scale, randomized, controlled study of LY IGlar versus IGlar in a 100% Chinese population. Second, this study will support the approval of LY IGlar in China, and therefore represents an important milestone in the development of treatment options for Chinese patients with T2D. The limitations of this study include the comparatively short 24‐week duration, as many similar studies have been designed with a 52‐week duration. However, the study results are consistent with ELEMENT 1, which showed equivalence of LY IGlar and IGlar at 24 and 52 weeks in patients with T1D.18 Second, this study included only insulin‐naive patients, and did not provide data for patients already receiving basal insulin treatment. Despite this, subgroup analyses of the ELEMENT 2 and 5 studies showed that the efficacy and safety of LY IGlar and IGlar were comparable in both insulin‐naive and insulin‐experienced patients with T2D.16, 17 Finally, the current study was open label because insulin was provided in prefilled pen injectors, which precluded double blinding. This is in contrast to the double‐blind ELEMENT 2 trial, in which insulin was provided as vial and syringe.16 However, delivery of insulin via prefilled pen injectors is representative of the real‐world use of insulin and allows patients to more accurately adjust their insulin dose.

In conclusion, once‐daily LY IGlar and IGlar, in combination with OAMs, had equivalent antihyperglycaemic efficacy and a comparable safety profile in insulin‐naive Chinese patients with T2D. These results represent the first data from a prospective, randomized study conducted in a 100% East Asian patient population showing the equivalence of LY IGlar and IGlar and add to previous similar findings from the global trials. LY IGlar provided a well‐tolerated and effective once‐daily basal insulin option for the treatment of patients with T2D in combination with OAMs, with an efficacy and safety profile comparable with IGlar.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

SJ and LD are employees of Eli Lilly. DZ, WC and WF declare no financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.14392.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. XXX.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the investigators and patients who participated in this study and Fernanda Rodrigues Anderson for providing consultation for the Materials and Methods section of the paper. Editorial support for this manuscript was paid for by Eli Lilly and provided by Jake Burrell, PhD (Rude Health Consulting). This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Feng W, Chen W, Jiang S, Du L, Zhu D. Efficacy and safety of LY2963016 insulin glargine versus insulin glargine (Lantus) in Chinese adults with type 2 diabetes: A phase III, randomized, open‐label, controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23:1786–1794. 10.1111/dom.14392

Wenhuan Feng and Wei Chen contributed equally and should be considered co‐first authors.

Funding information Eli Lilly and Company

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor R. Type 2 diabetes: etiology and reversibility. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1047‐1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology ‐ clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan ‐ 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):1‐87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 update to: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020;43:487‐493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association . 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes‐2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S111‐S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association . 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes‐2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S73‐S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Long‐acting insulin analogues versus NPH human insulin in type 2 diabetes: a meta‐analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;81:184‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilgenfeld R, Seipke G, Berchtold H, Owens DR. The evolution of insulin glargine and its continuing contribution to diabetes care. Drugs. 2014;74:911‐927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamb YN, Syed YY. LY2963016 insulin glargine: a review in type 1 and 2 diabetes. BioDrugs. 2018;32:91‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Medicines Agency . Abasaglar (previously Abasria). 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=/pages/medicines/human/medicines/002835/human_med_001790.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 12.European Medicines Agency . Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products. October 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/10/WC500176768.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 13.European Medicines Agency . Guideline on Similar Biological Medicinal Products Containing Biotechnology‐Derived Proteins as Active Substance: Quality Issues (revision 1). May 2014. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/06/WC500167838.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- 14.Davies M, Dahl D, Heise T, Kiljanski J, Mathieu C. Introduction of biosimilar insulins in Europe. Diabet Med. 2017;34:1340‐1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Announcement of the State Food and Drug Administration on Issuing the Technical Guidelines for the Development and Evaluation of Biosimilar Drugs. https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/yaopin/ypggtg/ypqtgg/20150228155701114.html. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- 16.Rosenstock J, Hollander P, Bhargava A, et al. Similar efficacy and safety of LY2963016 insulin glargine and insulin glargine (Lantus®) in patients with type 2 diabetes who were insulin‐naïve or previously treated with insulin glargine: a randomized, double‐blind controlled trial (the ELEMENT 2 study). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:734‐741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollom RK, Ilag LL, Lacaya LB, Morwick TM, Ortiz CR. Lilly insulin glargine versus Lantus(®) in insulin‐naïve and insulin‐treated adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial (ELEMENT 5). Diabetes Therapy. 2019;10:189‐203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blevins TC, Dahl D, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of LY2963016 insulin glargine compared with insulin glargine (Lantus®) in patients with type 1 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial: the ELEMENT 1 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:726‐733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan V, Ahn KJ, Cho YM, et al. Lilly insulin glargine versus Lantus(®) in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: India and East Asia subpopulation analyses of the ELEMENT 5 study. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39:745‐756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki . Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:2‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wangge G, Putzeist M, Knol MJ, et al. Regulatory scientific advice on non‐inferiority drug trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma RC, Chan JC. Type 2 diabetes in East Asians: similarities and differences with populations in Europe and the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281:64‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LANTUS® (insulin glargine injection) Prescribing Information . https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/021081s072lbl.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. XXX.

Data Availability Statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.