Abstract

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is a chronic inflammatory condition where crops of sterile pustules with erythematous keratotic lesions causing bleeding and pain appear on the palms and soles. Recently, the European Rare and Severe Expert Network considered PPP as a variant of pustular psoriasis with or without psoriasis vulgaris.

The prevalence of PPP varies from 0.050 to 0.12%. PPP occurs more frequently in women and the highest prevalence occurred between the ages of 50 and 69 years. Nail psoriasis seems to be frequent in PPP, ranging from 30 to 76%, and psoriatic arthritis in 8.6 to 26% of PPP patients.

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome and pustulotic arthro-osteitis are considered PPP-associated disorders. PPP has been reported with other co-morbidities such as psychiatric disorders, thyroid-associated disease, altered calcium homeostasis, gluten sensitivity diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, but larger studies are required to prove such associations. Environmental exacerbating factors might contribute to the onset or worsening of PPP such as cigarette smoking, stress, focal infections, metal allergies, and drug intake. Genetic predisposition plays an important role in PPP.

In PPP, both the innate and the adaptive immune systems are activated. The acrosyringeal expression of IL-17 has been demonstrated, indicating that the eccrine sweat gland is an active component of the skin barrier and an immune-competent structure. Increased levels of several inflammatory molecules, including IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-23A, and IL-23 receptor, have been detected in PPP biopsies. Increased serum levels of TNF-α, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ have been detected in patients with PPP in comparison to healthy subjects, suggesting a similar inflammatory pattern to psoriasis vulgaris. Oral and tonsillar infections serve as trigger factors for PPP.

Long-term therapy is required for many patients, but high-quality data are limited, contributing to uncertainty about the ideal approach to treatment.

Keywords: Palmoplantar pustulosis, psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, therapy

Definition and classification

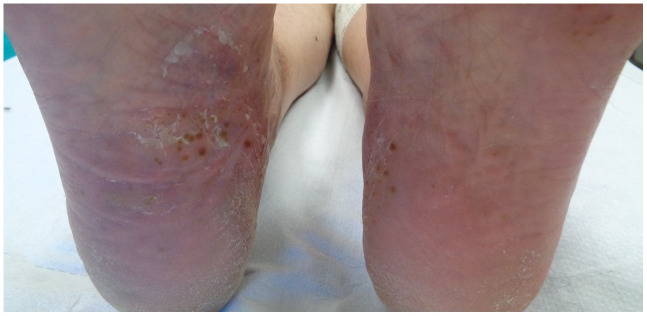

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by the recurrent appearance of crops of sterile pustules on the palms and soles (Figure 1 and Figure 2), in conjunction with erythematous keratotic lesions that tend to crack, causing bleeding and pain1–4.

Figure 1. Crops of sterile pustules on the right sole.

This image was taken in CM’s clinic for the purpose of this manuscript.

Figure 2. Crops of sterile pustules on both soles.

This image was taken in CM’s clinic for the purpose of this manuscript.

In 1930, Barber assigned this condition the name PPP and categorized it as a local pustular form of psoriasis, but this entity’s etiology and its links to other pathologies are still in contention1,2,4,5. Some proposed that PPP is a separate entity, despite PPP and PV sharing particular phenotypes, and in 2007 the International Psoriasis Council separated PPP and psoriasis into distinct entities1,2,4–6. In 2017, the European Rare and Severe Expert Network (ERASPEN) distinguished between psoriasis vulgaris (PV) and pustular psoriasis (PP) and recognized them as distinct phenotypes1,2,4–6. PPP was considered a variant of PP with the subclassification with or without PV7. Such classification of PPP as a form of PP is not widely accepted, mainly in Japan where PPP is considered as a separate disease from palmoplantar PP (PPPP)8.

Epidemiology

Epidemiologic data regarding PPP are limited. The prevalence of PPP across studies varies from 0.050% in Sweden, 0.051% in Korea, and 0.091% in Germany to 0.12% in Japan1,9.

PPP occurs more frequently in women than in men; observational studies from across the world have found proportions of female patients ranging from 58 to 94%1,2. The age of onset of PPP is usually between the fourth and the fifth decades; the mean age of onset in a retrospective study that we conducted including 39 patients was 48 years2. In a nationwide Japanese study published in 2015, the highest prevalence for PPP occurred between the ages of 50 and 69 years9.

The prevalence of PV among PPP patients ranges from 14 to 61%10–13. Nail involvement (nail psoriasis) in PPP seems to be frequent, ranging from 30 to 76%2. A recent study conducted in Seoul evaluated nail involvement in PPP, observing a high prevalence (66.3%) and a correlation between nail changes and severity of the disease, and the predominant findings were onycholysis and crumbling14. In Northern European populations, nail involvement has been reported in one-third of cases, with subungual pustulation13.

The prevalence of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in PPP patients has been reported to be from 8.6 to 26%1,2,13,14.

Clinical presentation and severity assessment

PPP’s main clinical characteristic consists of sterile pustules from 1 to 10 mm located on the palms and/or soles with bilateral involvement that might be asymmetrical1,2. The pustules usually arise in an erythematous base associated or not with crusting, desquamation, fissures, and/or hyperkeratosis1,2. The pustules tend to coalesce, resolving after several days with brown macules and/or the formation of hyperkeratotic plaques resembling plaque psoriasis1,2. The involvement of both palms and soles seems to be frequent; the thenar or hypothenar eminences and the central palm are common sites of involvement1,2,6. The instep, the medial and lateral borders of the foot across from the instep, and the sides or back of the heel are common sites on the feet1,2,6. Diffuse involvement of the whole palmoplantar area is seen in more severe cases1,2,6. PPP is characterized by a recurrent course, the severity does not appear to attenuate over time, and the risk of relapse remains during the patient’s lifetime15,16.

The impairment of quality of life (QoL) can be significant owing to symptoms such as burning, pain, itch, bleeding of fissures, and complications such as subcutaneous skin infections (erysipelas and cellulitis) that might require hospital admission1,2. Severe eruptions might impair the capacity to work, walk, or exercise1. In 2017, Trattner et al. in a cross-sectional study demonstrated a direct correlation between severity, measured by PalmoPlantar Pustulosis Severity Index (PPPASI), and QoL impairment, measured by Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), data recently confirmed in a larger study including UK and Northern European patients10,16. PPP severity seems to be higher in female versus male patients and in current or past smokers10.

Histology

PPP is characterized by the presence of pustules filled with neutrophils and eosinophils in the upper epidermis, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and parakeratosis, and loss of the granular layer1,17–20. Spongiosis and epidermal vesicle formation is usually seen in the early stages of PPP1. A mixed perivascular and diffuse infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and mast cells is present in the dermis with accumulation of eosinophils and mast cells bellow the pustule1,19,20. In 2019, Masuda-Kuroki et al., comparing the histologic presentations of PPP and pompholyx, found two main key features that differentiated both diseases: the presence of vesicles with spongiosis in pompholyx and microabscesses on the edges of vesicles in PPP17. Hyaluronate accumulation in the epidermis and presence of acantholytic keratinocytes covered with hyaluronate are additional features typical of pompholyx and absent in PPP18.

PPP-associated disorders

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome is a very rare condition that is more frequent in Asia and characterized by the presence of synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis1. It may present with PPP or other neutrophilic diseases (acne conglobata, acne fulminans, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and PP) and is associated with anterior chest wall arthropathy1.

Pustulotic arthro-osteitis (PAO), involving the anterior chest wall, is frequently (20–30%) reported in Japanese patients with PPP; focal infections are a known trigger factor1,21. PAO is more prevalent than SAPHO syndrome, and both diseases are characterized by increased uptake in bone scintigraphy of the anterior chest wall21.

PPP comorbidities

The relationship between PPP and systemic diseases is controversial1. Psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and manic-depressive disease) have been reported with a high incidence among female PPP patients (23–24%) compared to healthy controls (5%)22. Some authors have reported hypertension, thyroid-associated disease, altered calcium homeostasis, diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia, but larger studies are required to prove such associations16,22. Increased prevalence of gluten sensitivity in PPP patients was reported in a Swedish study, but these findings were not confirmed in the German and Austrian populations, suggesting geographical or ethnic variability16.

Trigger factors

Several studies have suggested that environmental exacerbating factors might contribute to the onset or worsening of PPP such as cigarette smoking, stress, focal infections, metal allergies, and drug intake1,22.

Tobacco smoke

The high prevalence of current or past smoking in PPP patients (42 to 100%) suggests a role in the pathogenesis of the disease; smoking withdrawal seems to improve the severity of PPP23. Nicotine has been suggested to exert a role on the sweat glands or on the keratinocytes, increasing cornification and promoting neutrophilic inflammation1,22. Differences in nicotine acetylcholine receptor staining patterns in PPP skin have revealed an abnormal response to nicotine that might contribute to inflammation1,22. Recently, Kobayashi et al. demonstrated a direct relationship between the severity of PPP (measured by PPPASI) and smoking index in female PPP patients. Moreover, they demonstrated that there was a synergistic release of IL-17A and IL-36γ after exposure to cigarette smoke extract; IL-36γ was highly expressed in tonsillar epithelial cells of PPP patients in comparison with patients without PPP, suggesting that IL-36γ production might occur in tonsil tissues as a result of a smoking habit24.

Focal infections and microbiome

Acute or chronic infections such as sinusitis, dental infection, and tonsilitis have been identified as trigger factors for PPP1. In 2017, Kuono et al. demonstrated that oral focal infections are directly related to PPP severity and the control of such infections with the use of tonsillectomy improves disease severity25. Recently, a higher incidence of oral dysbiosis in PPP patients has been demonstrated as compared to healthy subjects26,27. In addition, Kuono et al. suggested that oral dysbiosis in Japanese patients might play a role in both PPP and PAO4. Several authors have described the presence of microbiome inside the pustules in 30% of cases, in particular Pseudonocardia, Devosia, and Staphylococcus, which are the most frequent species among smokers, and recently also of Malassezia spp.3,28. Takahara et al. in 2018 demonstrated the positive role of tonsillectomy in improving PPP lesions29.

Stress

PPP patients report worsening or new onset of lesions during stressful times, and high levels of anxiety have been reported in such patients1. An increased number of contacts between nerves and mast cells and intense substance P-like immunoreactivity in neutrophils in pustules and the papillary dermis of PPP patients suggest a role for neuro-mediation in the inflammatory process1.

Drug intake

Paradoxical adverse events (PAEs) associated with biological therapy, mainly during anti-TNF-α therapy, have been reported in 2–5% of patients; PPP is the most common skin manifestation of PAE30,31. The new onset of PPP in such patients represents an ongoing type-I IFN-driven innate immune response in the absence of T cell-driven inflammation30. Interestingly, type-I IFN is the main inflammatory pathway involved in acute and unstable psoriasis forms such as guttate, erythrodermic psoriasis, and PPP induced by anti-TNF-α therapies32.

Metal allergies

In the literature, there are different isolated reports of the association of PPP and allergies. In a systematic review covering 519 PPP patients, the frequency of allergies among PPP patients was 22.7%; among the identified allergens, 84.3% of cases corresponded to metal allergies33. The exacerbation of PPP lesions after patch-test (effect only described with metals and not with other allergens) and the improvement of PPP in 65% of cases after withdrawal from metal contact support these findings33.

Genetic background

PPP has been considered a separate disease from PV by the International Psoriasis Council based on genetic differences, mainly the fact that PPP is not associated with the most common PV locus, PSORS1, but it is worth noting that many other genetic links between the two diseases have been found1. Variations of IL19, IL20, and IL24 genes have been reported as risks factors for both diseases1,34–36. In addition, missense variants in the CARD14 gene have been detected in both PPP as well as PV and generalized PP (GPP)34,35. Recently, mutations in AP1S3 have been described in PPP patients, representing another overlap of genetic risk factor among psoriasis, PPP, and GPP1,34–36. The ATG16L1 mutation in a gene located on chromosome 2 that plays a role in the immunological response of psoriasis, by affecting the production of antimicrobial peptides and the production of IL-18 and IL-1, leads to a propagating systemic inflammation that has been detected in both PPP and PV (with single nucleotide polymorphisms)1,34–37. IL36RN loss-of-function mutation induces the activation of IL-36 signaling, causing unregulated cytokine release and skin inflammation manifested mainly as GPP37. The frequency of IL36RN mutations among GPP patients is high (75–80%); such mutations have also been described in acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (ACH), in inverse psoriasis associated with PP, and in PPP with a lower frequency, suggesting a common genetic predisposition for all forms of PP, some of them associated with PV38. Such a link between PP and PV is supported by the genetic findings of PPP patients with and without concomitant plaque psoriasis; gene expression microarray studies of skin biopsies from PPP with concomitant plaque psoriasis and skin biopsies from PPP without concomitant plaque psoriasis have revealed that PPP with or without concomitant plaque psoriasis cannot be distinguished on the basis of gene expression, which suggests a relationship between these conditions1,34. Increased expression of the IL17 gene without an increase in IL-23 gene expression has been found in PPP, both with and without concomitant plaque psoriasis1,34.

Pathogenesis

In PPP, both the innate and the adaptive immune systems play a role, in addition to environmental factors and genetic susceptibility1. The intraepidermal sweat duct (acrosyringium) appears to be the primary site of inflammation, where vesicle/pustule formation takes place in PPP1,39. The acrosyngeal expression of IL-17 has been demonstrated, indicating that the eccrine sweat gland is an active component of the skin barrier and an immune-competent structure40.

Abnormalities of eccrine sweat gland function in the palmoplantar region might contribute to the formation of vesicles and pustules in PPP1. Increased access to medical care for PPP patients in the summer season compared with the cold season suggests a role for sweating as a trigger for PPP1. Increased numbers of Langerhans cells around the eccrine sweat ducts point towards an antigen-driven process associated with infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells that destroys the acrosyringium. Increased levels of several inflammatory molecules, including IL-8 (neutrophil chemoattractant), IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-23A, and IL-23 receptor, have been detected in PPP biopsies1. Increased serum levels of TNF-α, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ have been detected in patients with PPP in comparison to healthy subjects, suggesting a similar inflammatory pattern to PV1,39–43. In the acrosyringium, there is overexpression of IL-17, IL-8, and IL-36γ1,39–43. Such expression is induced by antimicrobial peptides as LL-37 or TLN-58, suggesting that targeting IL-17 might not be sufficient to control the disease1,39–43. Oral and tonsillar infections serve as trigger factors for PPP1,44. A hyperimmune response to streptococci has been demonstrated in tonsillar mononuclear cells of PPP patients, suggesting that tonsillar-induced autoimmune/inflammatory responses might play a role in PPP pathogenesis44. Cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA), chemokine receptor CCR6, and beta1-integrin serve in the recruitment of T cells from the tonsils to the skin44.

Innate immunity is upregulated in PPP lesions, as demonstrated by the high expression of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-36γ. IL-1β is the main inducer of lipocalin 2 (LCN2) production by keratinocytes. LCN2 is a potential blood biomarker candidate for PPP, capable of chemoattraction of neutrophils, seen not only in PPP but also in hidradenitis suppurativa45. IL-8 is overexpressed in PPP skin biopsies compared to PV and healthy skin; this finding has been proved in a clinical setting using an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody that obtained a good clinical response in PPP but has failed to obtain efficacy in a phase II trial in PV43.

IL-36γ levels have been found to be increased in PPP and PV lesions compared to healthy skin; positive staining can be seen in the sweat duct cells in the dermis and in keratinocytes nearby PPP pustules, suggesting a role in pustule formation. IL-36γ promotes IL-8 secretion by keratinocytes, which leads to chemoattraction of neutrophils and results in pustule formation41,43.

Personal view

In the last 10 years, it has been proposed that the onset of aseptic pustular lesions in the palms and soles be classified into two different conditions: PPP and PPPP. Both entities share the same clinical presentation on the palmoplantar area and identical nail features, concomitant PsA may be present in both, and the histopathologic findings are quite similar. The key differentiating points are the presence of PV in other sites and the higher frequency of a family history of psoriasis in the PPPP variant. PPP has been recently classified as a form of PP, and it is worth noting that GPP and ACH are also forms of PP that could be associated with PV or not, but only in the case of PPP has a separate entity—such as PPPP—been proposed. From a genetic point of view, PV and PP share some common genetic susceptibility links and certainly differ by the higher prevalence of PSORS1 in PV. Regarding therapy, PPP seems to be more difficult to treat than PV, but such a lower response to both conventional and biological therapies has also been seen on palmoplantar plaque psoriasis46.

Considering all the previously cited factors, we consider the term PPP with or without PV enough to describe the condition; furthermore, nomenclature uniformity allows a better recognition of the disease.

New therapeutic options

As PPP is a chronic and recurrent disease with a high impact on QoL, long-term therapy is required for many patients, but high-quality data are limited (small sample sizes in randomized controlled trials [RCTs], geographical variability), contributing to uncertainty about the ideal approach to treatment47. Recently, new biological and non-biological molecules have been investigated in PPP patients47,48.

Several case reports have recorded the efficacy of TNF-α-blocking agents in PPP despite the paradoxical onset during such therapies46,48. One 24-week clinical trial supports the role of etanercept for PPP, and further evidence of efficacy in several cases affected by SAPHO syndrome have been reported under different TNF-α-blocking agents (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab)49.

A 16-week RCT failed to achieve efficacy in PPP patients treated with ustekinumab (45 mg given at weeks 0 and 4) versus placebo, but several reports (case series and one uncontrolled study) using a higher dose (90 mg) of ustekinumab demonstrated efficacy in PPP patients50–53.

Anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibodies have been tested on PPP. The 2PRECISE trial evaluated secukinumab at 300 mg or 150 mg versus placebo given at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 and then every 4 weeks54. The trial did not achieve the primary endpoint of superiority of secukinumab (300 or 150 mg doses) over placebo at week 16 (PPPASI-75 achieved by 27%, 18%, and 14%, respectively)54. But, in the long-term, at week 52, non-responders of the secukinumab and the placebo arms were treated with 300 mg every 4 weeks with 42% PPPASI-75 efficacy and 150 mg with 35% PPPASI-75 efficacy54. Only case reports regarding other anti-IL-17 therapies are available, with lack of efficacy of brodalumab in four PPP cases, but a phase III RCT is ongoing43,55.

Anti-IL-23 therapies seem to be promising for PPP patients. Two phase III RCTs demonstrated the efficacy of guselkumab versus placebo in PPP56,57. In the guselkumab 100 mg group, 57% of PPP patients had at least 50% improvement in PPPASI total score (PPPASI-50) at week 16 compared to 34% in the placebo group56,57. At week 52, PPPASI-75 was reached in 55.6% of patients treated with 100 mg and in 59.6% of patients treated with 200 mg of guselkumab56,57.

The systemic retinoid alitretinoin has been evaluated in a few PPP patients, demonstrating a 45.2% improvement at week 24, but this result was not significantly better than placebo; additional studies are required58. Few cases reports and two retrospective studies have reported the efficacy of apremilast in PPP both in monotherapy and in association with other systemic therapies, but RCTs are missing59,60. Until today, there are no reports regarding the use of ixekizumab, risankizumab, or tildrakizumab in PPP. Improvement in PPP and ACH has been recorded during treatment with anakinra in a few case reports43,47. Canakinumab has been found to be ineffective for PPP in one report43,47. The APRICOT trial is currently evaluating anakinra versus placebo for PP, but the results are still awaited61.

New molecules under development for PPP include an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody (HuMab 10F8) that in an open-label trial has demonstrated a decrease of 50% or more in new pustule formation at week 8 in 67% of PPP patients43. In addition, an oral formulation that blocks CXCR2 (IL-8B receptor), RIST4721, is currently under investigation in a phase IIa RCT43.

Blocking the IL-36 pathway has recently been under the spotlight for PP, and for GPP in particular62. One phase IIb dose-finding RCT is currently evaluating the PPPASI response at week 16 for spesolimab in PPP as the primary endpoint, and a phase IIa RCT of spesolimab versus placebo is currently ongoing, with PPPASI-50 at week 16 as the primary outcome43. We need to wait for the results of such studies to understand the potential role of anti-IL-36 therapies in PPP.

The peer reviewers who approve this article are:

Luís Puig, Department of Dermatology, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Yukari Okubo, Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan

Funding Statement

The authors declare that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

References

- 1.Brunasso G, Massone C: Palmoplantar pustulosis: Epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on January 04, 2021). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunasso AMG, Puntoni M, Aberer W, et al. : Clinical and epidemiological comparison of patients affected by palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: A case series study. Br J Dermatol. 2013; 168(6): 1243–51. 10.1111/bjd.12223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masuda-Kuroki K, Murakami M, Tokunaga N, et al. : The microbiome of the "sterile" pustules in palmoplantar pustulosis. Exp Dermatol. 2018; 27(12): 1372–7. 10.1111/exd.13791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouno M, Akiyama Y, Minabe M, et al. : Dysbiosis of oral microbiota in palmoplantar pustulosis patients. J Dermatol Sci. 2019; 93(1): 67–9. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 5.Brunasso AMG, Massone C: Psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: An endless debate? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017; 31(7): e335–e337. 10.1111/jdv.14131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunasso AMG, Massone C: Can we really separate palmoplantar pustulosis from psoriasis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24(5): 619–21; author reply 621. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03648.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. : European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017; 31(11): 1792–9. 10.1111/jdv.14386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami M, Terui T: Palmoplantar pustulosis: Current understanding of disease definition and pathomechanism. J Dermatol Sci. 2020; 98(1): 13–9. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 9.Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, et al. : Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: A nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(1): e006450. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benzian-Olsson N, Dand N, Chaloner C, et al. : Association of Clinical and Demographic Factors With the Severity of Palmoplantar Pustulosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020; 156(11): 1216–22. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 11.Andersen YMF, Augustin M, Petersen J, et al. : Characteristics and prevalence of plaque psoriasis in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2019; 181(5): 976–82. 10.1111/bjd.17832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 12.Huang CM, Tsai TF: Clinical characteristics, genetics, comorbidities and treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis: A retrospective analysis of 66 cases in a single center in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2020; 47(9): 1046–9. 10.1111/1346-8138.15470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 13.Brunasso AMG, Massone C: Clinical characteristics, genetics, comorbidities and treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis: A different perspective. J Dermatol. 2021; 48(1): e47. 10.1111/1346-8138.15644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim M, Yang S, Kim BR, et al. : Nail involvement features in palmoplantar pustulosis. J Dermatol. 2021; 48(3): 360–5. 10.1111/1346-8138.15716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 15.Kharawala S, Golembesky AK, Bohn RL, et al. : The clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of palmoplantar pustulosis: A structured review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020; 16(3): 253–66. 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1708194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 16.Trattner H, Blüml S, Steiner I, et al. : Quality of life and comorbidities in palmoplantar pustulosis - a cross-sectional study on 102 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017; 31(10): 1681–5. 10.1111/jdv.14187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuda-Kuroki K, Murakami M, Kishibe M, et al. : Diagnostic histopathological features distinguishing palmoplantar pustulosis from pompholyx. J Dermatol. 2019; 46(5): 399–408. 10.1111/1346-8138.14850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 18.Murakami M, Muto J, Masuda-Kuroki K, et al. : Pompholyx vesicles contain small clusters of cells with high levels of hyaluronate resembling the pustulovesicles of palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2019; 181(6): 1325–7. 10.1111/bjd.18261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 19.Eriksson MO, Hagforsen E, Lundin IP, et al. : Palmoplantar pustulosis: A clinical and immunohistological study. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 138(3): 390–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoon SY, Park HS, Lee JH, et al. : Histological differentiation between palmoplantar pustulosis and pompholyx. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013; 27(7): 889–93. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 21.Yamamoto T, Hiraiwa T, Tobita R, et al. : Characteristics of Japanese patients with pustulotic arthro-osteitis associated with palmoplantar pustulosis: A multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2020; 59(4): 441–4. 10.1111/ijd.14788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 22.Hagforsen E, Michaëlsson K, Lundgren E, et al. : Women with palmoplantar pustulosis have disturbed calcium homeostasis and a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and psychiatric disorders: A case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005; 85(3): 225–32. 10.1080/00015550510026587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michaëlsson G, Gustafsson K, Hagforsen E: The psoriasis variant palmoplantar pustulosis can be improved after cessation of smoking. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006; 54(4): 737–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi K, Kamekura R, Kato J, et al. : Cigarette Smoke Underlies the Pathogenesis of Palmoplantar Pustulosis via an IL-17A-Induced Production of IL-36γ in Tonsillar Epithelial Cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2021; 141(6): 1533–1541.e4. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 25.Kouno M, Nishiyama A, Minabe M, et al. : Retrospective analysis of the clinical response of palmoplantar pustulosis after dental infection control and dental metal removal. J Dermatol. 2017; 44(6): 695–8. 10.1111/1346-8138.13751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kageyama Y, Shimokawa Y, Kawauchi K, et al. : Dysbiosis of Oral Microbiota Associated with Palmoplantar Pustulosis. Dermatology (Basel). 2021; 237(3): 347–56. 10.1159/000511622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 27.Nibali L, Henderson B, Sadiq ST, et al. : Genetic dysbiosis: The role of microbial insults in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Oral Microbiol. 2014; 6. 10.3402/jom.v6.22962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto Y, Harada K, Maeda T, et al. : Molecular detection of fungal and bacterial DNA from pustules in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis: Special focus on Malassezia species. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020; 45(1): 36–40. 10.1111/ced.14026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 29.Takahara M, Hirata Y, Nagato T, et al. : Treatment outcome and prognostic factors of tonsillectomy for palmoplantar pustulosis and pustulotic arthro-osteitis: A retrospective subjective and objective quantitative analysis of 138 patients. J Dermatol. 2018; 45(7): 812–23. 10.1111/1346-8138.14348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. : TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018; 9(1): 25. 10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 31.Brunasso AMG, Massone C: Plantar pustulosis during rituximab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67(4): e148–50. 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conrad C, Gilliet M: Psoriasis: From Pathogenesis to Targeted Therapies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018; 54(1): 102–13. 10.1007/s12016-018-8668-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunasso VAMG, Puntoni M, Massone C: Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Allergies: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2019; 9(2): 105–10. 10.5826/dpc.0902a05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. : Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019; 143(3): 1021–6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 35.Mössner R, Wilsmann-Theis D, Oji V, et al. : The genetic basis for most patients with pustular skin disease remains elusive. Br J Dermatol. 2018; 178(3): 740–8. 10.1111/bjd.15867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Douroudis K, Kingo K, Traks T, et al. : ATG16L1 gene polymorphisms are associated with palmoplantar pustulosis. Hum Immunol. 2011; 72(7): 613–5. 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freitas E, Rodrigues MA, Torres T: Diagnosis, Screening and Treatment of Patients with Palmoplantar Pustulosis (PPP): A Review of Current Practices and Recommendations. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020; 13: 561–78. 10.2147/CCID.S240607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 38.Wang TS, Chiu HY, Hong JB, et al. : Correlation of IL36RN mutation with different clinical features of pustular psoriasis in Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016; 308(1): 55–63. 10.1007/s00403-015-1611-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagforsen E, Hedstrand H, Nyberg F, et al. : Novel findings of Langerhans cells and interleukin-17 expression in relation to the acrosyringium and pustule in palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2010; 163(3): 572–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murakami M, Ohtake T, Horibe Y, et al. : Acrosyringium is the main site of the vesicle/pustule formation in palmoplantar pustulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010; 130(8): 2010–6. 10.1038/jid.2010.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiaoling Y, Chao W, Wenming W, et al. : Interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-36γ but not IL-36Ra are related to acrosyringia in pustule formation associated with palmoplantar pustulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019; 44(1): 52–7. 10.1111/ced.13689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 42.Murakami M, Kaneko T, Nakatsuji T, et al. : Vesicular LL-37 contributes to inflammation of the lesional skin of palmoplantar pustulosis. PLoS One. 2014; 9(10): e110677. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L: Palmoplantar Pustulosis: Recent Advances in Etiopathogenesis and Emerging Treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21(3): 355–70. 10.1007/s40257-020-00503-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 44.Harabuchi Y, Takahara M: Pathogenic role of palatine tonsils in palmoplantar pustulosis: A review. J Dermatol. 2019; 46(11): 931–9. 10.1111/1346-8138.15100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 45.Wolk K, Frambach Y, Jacobi A, et al. : Increased levels of lipocalin 2 in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2018; 90(1): 68–74. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunasso AMG, Puntoni M, Delfino C, et al. : Different response rates between palmoplantar involvement and diffuse plaque psoriasis in patients treated with infliximab. Eur J Dermatol. 2012; 22(1): 133–5. 10.1684/ejd.2011.1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunasso G, Massone C: Palmoplantar pustulosis: Treatment. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on January 04, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kromer C, Wilsmann-Theis D, Gerdes S, et al. : Drug survival and reasons for drug discontinuation in palmoplantar pustulosis: A retrospective multicenter study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019; 17(5): 503–16. 10.1111/ddg.13834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 49.Bissonnette R, Poulin Y, Bolduc C, et al. : Etanercept in the treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008; 7(10): 940–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morales-Múnera C, Vilarrasa E, Puig L: Efficacy of ustekinumab in refractory palmoplantar pustular psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013; 168(4): 820–4. 10.1111/bjd.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hegazy S, Konstantinou MP, Bulai Livideanu C, et al. : Efficacy of ustekinumab in palmoplantar pustulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32(5): e204–e206. 10.1111/jdv.14718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buder V, Herberger K, Jacobi A, et al. : Ustekinumab in der Therapie der Pustulosis palmoplantaris - Eine Fallserie mit neun Patienten. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016; 14(11): 1109–15. 10.1111/ddg.12825_g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obeid G, Do G, Kirby L, et al. : Interventions for chronic palmoplantar pustulosis: Abridged Cochrane systematic review and GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2021; 184(6): 1023–1032. 10.1111/bjd.19560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 54.Mrowietz U, Bachelez H, Burden AD, et al. : Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in moderate to severe palmoplantar pustular psoriasis over 148 weeks: Extension of the 2PRECISE study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021; 84(2): 552–4. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 55.Pinter A, Wilsmann-Theis D, Peitsch WK, et al. : Interleukin-17 receptor A blockade with brodalumab in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis: Report on four cases. J Dermatol. 2019; 46(5): 426–30. 10.1111/1346-8138.14815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 56.Terui T, Kobayashi S, Okubo Y, et al. : Efficacy and Safety of Guselkumab in Japanese Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019; 155(10): 1153–61. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 57.Yamamoto T, Fukuda K, Morita A, et al. : Efficacy of guselkumab in a subpopulation with pustulotic arthro-osteitis through week 52: An exploratory analysis of a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in Japanese patients with palmoplantar pustulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020; 34(10): 2318–29. 10.1111/jdv.16355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 58.Brunasso AMG, Massone C: Alitretinoin therapy for palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2017; 177(2): 578–9. 10.1111/bjd.15605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eto A, Nakao M, Furue M: Three cases of palmoplantar pustulosis successfully treated with apremilast. J Dermatol. 2019; 46(1): e29–e30. 10.1111/1346-8138.14516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 60.Kato N, Takama H, Ando Y, et al. : Immediate response to apremilast in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis: A retrospective pilot study. Int J Dermatol. 2021; 60(5): 570–8. 10.1111/ijd.15382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation

- 61.Cro S, Patel P, Barker J, et al. : A randomised placebo controlled trial of anakinra for treating pustular psoriasis: Statistical analysis plan for stage two of the APRICOT trial. Trials. 2020; 21(1): 158. 10.1186/s13063-020-4103-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. : Inhibition of the Interleukin-36 Pathway for the Treatment of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380(10): 981–3. 10.1056/NEJMc1811317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Faculty Opinions Recommendation