Abstract

Background

Acne confers an increased risk of physical, psychiatric, and psychosocial sequelae, potentially affecting multiple dimensions of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Morbidity associated with truncal acne is poorly understood.

Objective

To determine how severity and location of acne lesions impact the HRQoL of those who suffer from it.

Methods

A total of 694 subjects with combined facial and truncal acne (F+T) and 615 with facial acne only (F) participated in an online, international survey. Participants self-graded the severity of their acne at different anatomical locations and completed the dermatology life quality index (DLQI).

Results

The F+T participants were twice as likely to report “very large” to “extremely large” impact on HRQoL (ie, DLQI > 10 and children's DLQI [CDLQI] > 12) as compared with the F participants (DLQI: odds ratio [OR] 1.61 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.02-2.54]; CDLQI: OR 1.86 [95% CI 1.10-3.14]). The impact of acne on HRQoL increased with increasing acne severity on the face (DLQI and CDLQI P values = .001 and .017, respectively), chest (P = .003; P = .008), and back (P = .001; P = .028).

Limitations

Temporal evaluation of acne impact was not estimated.

Conclusions

Facial and truncal acne was associated with a greater impact on HRQoL than facial acne alone. Increasing severity of truncal acne increases the adverse impact on HRQoL irrespective of the severity of facial acne.

Key words: CompAQ, dermatology life quality index (DLQI), facial acne, patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, truncal acne

Abbreviations used: CDLQI, children's dermatology life quality index; CI, confidence interval; CompAQ, Comprehensive Acne Quality of Life; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; F, facial acne only; F+T, combined facial and truncal acne; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; OR, odds ratio

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Facial and truncal acne has a significant impact on emotional well-being and everyday life activities.

-

•

The additional impact of truncal acne on quality of life implies that early and effective treatment of truncal acne is important to limit disease-related psychosocial sequelae.

Introduction

Acne is an inflammatory disease of pilosebaceous units with an estimated global prevalence (all ages) of 9.4%, ranking it among the top 10 most prevalent conditions worldwide.1,2 It primarily affects the face (99%) and less frequently the chest or back (ie, approximately half of the cases with facial acne).3,4 This inflammatory disorder typically develops during the teen years, affecting up to 100% of adolescents, and can continue into adulthood; some affected individuals can present with chronic unremitting disease.5,6 Overall, acne can inflict lifelong physical, psychiatric, and psychosocial sequelae, affecting multiple dimensions of the health-related quality of life (HRQoL).7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The psychosocial impacts of acne have been estimated to be similar to those of other chronic diseases such as asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, or arthritis.9 Although the impact of acne on HRQoL correlates with disease severity, patients with mild disease can also present with significant HRQoL impairment.24

Most prior HRQoL studies on acne have focused on facial acne.25,26 However, just as with facial acne, acne can affect the chest and back with varying severity, and the location of acne has been shown to differentially impact the patient's HRQoL experience.27, 28, 29 Evaluation of acne severity and impact beyond facial involvement can provide a means to develop a comprehensive patient management strategy. More recently, acne grading scales30 and acne specific HRQoL measures inclusive of both facial and truncal acne were developed to facilitate these assessments.31,32

In this cross-sectional survey, the goal was to determine the extent to which acne location affects HRQoL. This study investigated whether HRQoL impairment differs between those with facial acne only (F) versus those with facial and truncal acne (F+T).

Materials and methods

This was a cross-sectional, web-based survey of an online respondent panel aged ≥18 years (ie, Kantar LightSpeed GMI, Dynata, Toluna, M3, Lucid, BA) who had previously agreed to respond to health surveys about their medical condition(s) or those of their child. All participants of the study aged 13 to <18 years old were assented and permitted by their legal guardian. The research complied with General Data Protection Regulation, all international/local data protection legislation, and Insights Association/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research/European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association/British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association. All subjects provided informed consent prior to participation. Minors were required to answer the survey questions themselves. The survey was administered in the native language of each country (ie, United States of America, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and Brazil) between November 2019 and January 2020. Based on the formula [click through/panelists who received an email with the study link], the response rate of the survey was approximately 5%.

A quota sampling method based on geographic location was used to ensure that the sample of respondents was representative of acne populations in these countries. A weighting adjustment was applied at the country level if deviations were observed between the sample and the expected age and sex distribution of the acne population in these countries.33 Country weights were also used to account for population size. A comparison of key study results for weighted and unweighted data found no significant differences between both results’ analyses. This report is presented based on the weighted data.

After informed consent was obtained, the potential participants were asked to complete a sociodemographic questionnaire that was used to determine study eligibility. Inclusion criteria was defined as male or female subjects aged between 13 and 40 years who had self-reported a physician diagnosis of acne, who were currently being followed by a health care professional, and who were receiving prescription treatment for acne. The severity of the acne was assessed using a self-rated 6-category global acne grading system based on the Investigator Global Assessment for the face, which was modified to include the trunk (chest and back).30 To facilitate self-assessment of severity, photo-scales were provided as examples of severity for the face, chest, and back alongside text descriptions. Participants were required to have mild to very severe facial acne at the time of survey completion and moderate to very severe facial acne as their worst acne onset in the past 12 months to be included in the F group; to be included in the F+T group participants were also required to have the same level of severity on the chest and/or back at the time of survey completion and as their worst acne onset in the past 12 months.

The survey obtained information on demographics (eg, sex, age, and residential background) and clinical characteristics (eg, family history of acne, presence of acne signs/symptoms, the number of years living with the condition, body location and self-assessed severity of acne, current acne treatment, and appointments with a dermatologist). Photographs with examples of acne (eg, comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules) were provided to assist with self-recognition. In addition, the following validated HRQoL scales were administered: the dermatology life quality index (DLQI; for participants ≥ 16 years), children's DLQI (CDLQI; for participants < 16 years),31 and the Comprehensive Acne Quality of Life (CompAQ; all ages)34 referenced to the preceding week according to developer instructions. Linguistic translation and cultural adaptation were conducted in accordance with conventional methodology (TransPerfect, October 2019). Clinical experts (JT, BD) contributed to the development of the screening criteria, survey content, and selection of patient-reported outcome measures.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the survey (weighted) data set. For continuous variables, mean, standard error of the mean, and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. For categorical variables, frequencies were reported. This study presents aggregate results for all study countries. DLQI, CDLQI, and CompAQ were scored according to their respective guidances. DLQI and CDLQI consisted of 10 questions with 4 possible answers for each scored from 0 to 3. The overall response scores were 0-30 with higher scores indicating greater impairment of HRQoL. The clinical interpretation of the DLQI scores was as follows: score 0-1 = no effect at all on the patient's life; 2-5 = small effect on the patient's life; 6-10 = moderate effect on the patient's life; 11-20 = very large effect on the patient's life; 21-30 = extremely large effect on the patient's life; a score >10 indicates that the patient's life is being severely affected by their skin disease.31 The clinical interpretation of the CDLQI scores is as follows: a 0-1 = no effect at all on the patient's life; 2-6 = small effect on the patient's life; 7-12 = moderate effect on the patient's life; 13-18 = very large effect on the patient's life; 19-30 = extremely large effect on the patient's life; a score >12 indicates that the patient's life is being severely affected by their skin disease.35 CompAQ consisted of 20 questions, each with 9 possible answers with a score range of 0-8. The total score range was 0-160 with higher scores indicating greater impairment in HRQoL.

Continuous variables were analyzed using Student t test or analysis of variance with 1 or more independent variables if 1 of the variables being compared had 2 or more levels (eg, age groups). Categorical variables were analyzed by chi-square independence test with Yates' correction and by Fisher's exact test. All tests were 2-tailed and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Multivariate regression

Regression models were used to evaluate the differences in the HRQoL between the respondents with F+T versus F. Variables identified in the literature as likely to be independently associated risk factors for acne severity and impact on HRQoL were included in the multivariate analysis (ie, age, sex, urban vs rural residence and country of residence, family history of acne, and acne severity grade at each body site). Country was modeled as the primary sampling unit to account for clustering of data at the country level. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI were generated. The level of significance was set at P < .05. STATA version 15 (StataCorp LLC) was used for analyses.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 1309 respondents consented to participate in the study and were allocated into 2 study groups: F+T (n = 694) and F (n = 615). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table I. There were no significant differences in terms of age, sex, or other demographic characteristics between the F and F+T groups (Table I), nor among the F+T group with acne on the face and chest alone versus acne on the face and back alone (data not shown). Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar across age groups (ie, <16 years vs ≥16 years), but there were more female adults in the older age group (36.8% vs 50.9%, respectively, P = .020), and the duration of facial and truncal acne was significantly longer in the older age group (+6.8 years [P = .001] and +6.5 years [P = .001] for facial and truncal acne, respectively) (data not shown).

Table I.

Population demographics and acne characteristics

| F+T group |

F group |

|

|---|---|---|

| N = 694 | N = 615 | |

| Age (years), mean (95% CI) | 18.71 (17.3-20.1) | 18.50 (17.8-19.2) |

| Age <16 years, n (%) | 288 (46.8%) | 333 (48.0%) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Males | 385 (55.5%) | 349 (56.8%) |

| Females | 309 (44.5%) | 266 (43.2%) |

| Type of residence, n (%) | ||

| Urban | 412 (59.4%) | 364 (59.2%) |

| Suburban | 201 (29.0%) | 182 (29.7%) |

| Rural | 80 (11.6%) | 69 (11.1%) |

| Country, n (%) | ||

| United States | 323 (46.6%) | 293 (47.6%) |

| Canada | 33 (4.7%) | 45 (7.2%) |

| Brazil | 82 (11.9%) | 86 (13.9%) |

| Germany | 80 (11.6%) | 60 (9.7%) |

| France | 121 (17.4%) | 79 (12.9%) |

| Italy | 53 (7.7%) | 53 (8.6%) |

| Clinical characteristics of acne | ||

| Family history, n (%) | ||

| Yes∗ | 581 (85.4%) | 462 (78.0%) |

| Age at onset, mean (95% CI) | ||

| Facial acne∗ | 12.6 (12.3-13.0) | 13.1 (12.8-13.5) |

| Truncal acne | 13.1 (12.7-13.5) | NA |

| Acne duration at time of survey completion (years), mean (95% CI) | ||

| Facial acne | 6.1 (4.5-7.7) | 5.5 (4.4-6.5) |

| Truncal acne | 5.6 (4.3-6.8) | NA |

| Current acne severity: Face, n | 694 | 615 |

| Almost clear | 0 | 0 |

| Mild | 312 (45.0%) | 310 (50.4%) |

| Moderate | 249 (35.9%) | 240 (39.1%) |

| Severe | 113 (16.2%) | 57 (9.3%) |

| Very severe | 20 (2.9%) | 8 (1.3%) |

| Current acne severity: Back, n | 644 | 0 |

| Almost clear | 7 (1.0%) | |

| Mild | 208 (32.0%) | |

| Moderate | 287 (44.5%) | |

| Severe | 119 (18.4%) | |

| Very severe | 24 (3.7%) | |

| Current acne severity: Chest, n | 317 | 0 |

| Almost clear | 46 (14.7%) | |

| Mild | 123 (38.7%) | |

| Moderate | 91 (28.8%) | |

| Severe | 48 (15.3%) | |

| Very severe | 8 (2.6%) | |

F, Facial acne only group; F+T, facial and truncal acne group.

P values for the comparison of F+T versus F groups significant at <.05.

F+T respondents reported acne involvement on the face (100%), chest (45.6%), and back (92.8%) at the time of questionnaire completion; 54.3% of F+T respondents had acne on the face and back only, 7.3% had acne on the face and chest only, and 38.5% had acne on all 3 sites (ie, face, chest, and back). Table II presents the proportion of respondents with acne on the face and back and/or chest by acne severity.

Table II.

Correlation between the severity grade of acne on the face versus the back and chest

| Severity of facial acne | Without acne on the back |

Without acne on the chest |

Acne on the chest and back |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of acne on the chest |

Severity of acne on the back |

Severity of acne on the chest and back |

|||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe/very severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe/very severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe/very severe | |

| Mild, n (%) | 7 (1.0%) | 4 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 112 (16.1%) | 65 (9.4%) | 7 (1.0%) | 66 (9.5%) | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 5 (0.7%) | 21 (3.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 14 (2.0%) | 96 (13.8%) | 18 (2.6%) | 7 (1.0%) | 37 (5.3%) | 6 (0.9%) |

| Severe/very severe, n (%) | 2 (0.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 6 (0.9%) | 4 (0.6%) | 17 (2.4%) | 44 (6.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | 3 (0.4%) | 35 (5.0%) |

A higher proportion of F+T respondents self-reported severe or very severe facial acne compared with F respondents (19.2% vs 10.6%; P = .024) (Table I).

Impact on HRQoL

The impact of acne on all HRQoL scales was significantly higher in the F+T respondents than in the F respondents (ie, mean CDLQI scores of 15.12 [95% CI 11.6-18.6] and 12.47 [95% CI 9.8-15.2], respectively [P = .001]; mean DLQI scores of 12.85 [95% CI 11.5-14.2] and 10.78 [95% CI 10.1-11.4], respectively [P = .011]; mean CompAQ scores of 101.4 [95% CI 89.7-113.0] and 87.3 [95% CI 79.6-94.9], respectively [P = .014]).

The prevalence of those reporting CDLQI scores indicative of “very large” or “extremely large” HRQoL impact (ie, total score > 12) was 61.3% versus 45.2% for F+T versus F (P = .001); the prevalence of those reporting DLQI scores of “very large” or “extremely large” HRQoL impact (ie, total score > 10) was 57.3% versus 44.5% for F+T versus F (P = .015). This difference remained significant in multivariate models in which the F+T respondents were almost twice as likely to have scores in the range of “very large” or “extremely large” impact on HRQoL compared with the F group (DLQI: OR F+T vs F = 1.61 [95% CI 1.02-2.54], P = .042; CDLQI: OR 1.86 [95% CI 1.10-3.14], P = .028) (Table III).

Table III.

Odds ratios (ORs) for a score in the range of “very large” impact of facial and truncal acne in HRQoL (per CDLQI and DLQI) in adjusted logistic regression models with age, sex, acne location, and severity as explanatory variables

| Explanatory variables | CDLQI score >12 |

DLQI score >10 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Acne on both the face and trunk (F+T vs F) | 1.86 (1.10 to 3.14) | .028 | 1.61 (1.02 to 2.54) | .042 |

| Female vs male | 1.07 (0.72 to 1.60) | .672 | 0.93 (0.49 to 1.73) | .766 |

| Family history of acne: Yes | 1.93 (0.94 to 3.97) | .067 | 1.21 (0.78 to 1.89) | .317 |

| Urban vs rural residence | 2.06 (0.96 to 4.42) | .058 | 1.84 (1.02 to 3.33) | .046 |

| Unit increase in acne severity on face | 2.31 (1.26 to 4.24) | .017 | 2.25 (1.93 to 2.64) | .001 |

| Unit increase in acne severity on chest | 1.99 (1.32 to 3.02) | .008 | 2.20 (1.14 to 4.22) | .027 |

| Unit increase in acne severity on back | 2.40 (1.15 to 5.00) | .028 | 2.11 (1.62 to 2.75) | .001 |

Country was also included in the adjusted analyses. Acne severities at each body site were not included together in the same model because of collinearity.

CDLQI, Children's dermatology life quality index; CI, confidence interval; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; F, facial acne only; F+T, combined facial and truncal acne; OR, odds ratio.

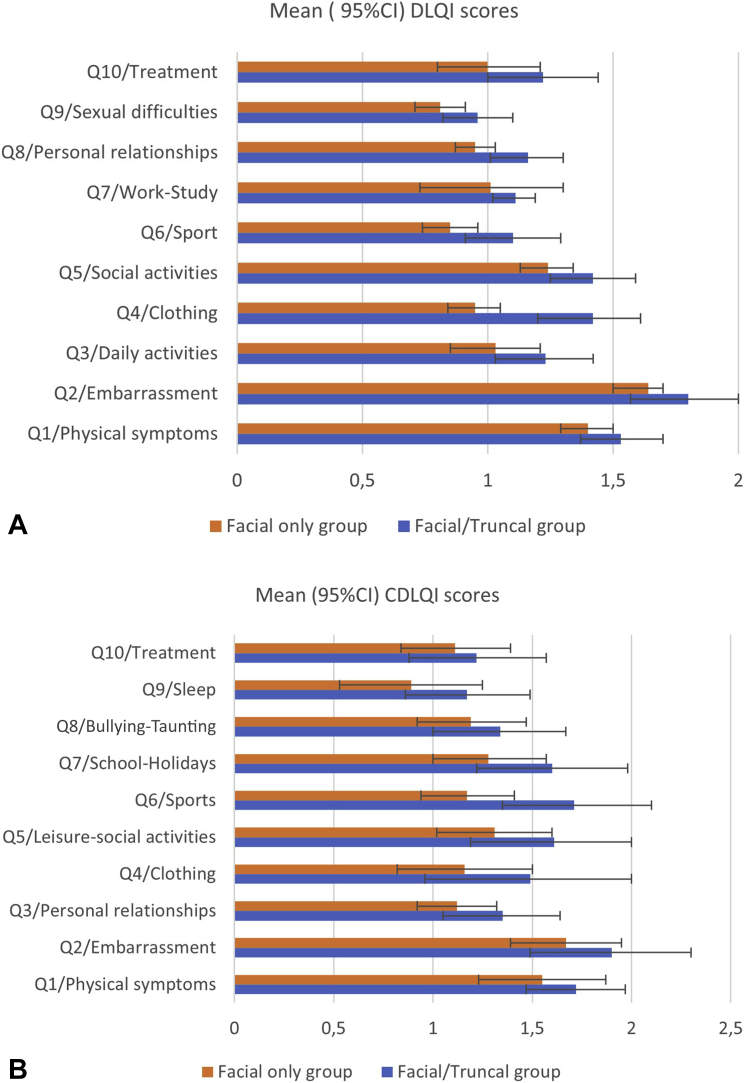

The majority of respondents (86.4% F+T and 91.5% F) reported being self-conscious because of their acne (P = .098 for the difference in proportions of F+T vs F). Significant differences between F+T and F were seen for both DLQI and CDLQI domains related to going out or clothing choice and participation in public activities and sports that revealed or made more visible their truncal acne (Fig 1, A and B).

Fig 1.

A, DLQI means (95% CI) for the “F+T” and “F” groups for individual questions. B, CDLQI means (95% CI) for the “F+T” and “F” groups for individual questions. CDLQI, Children's dermatology life quality index; CI, confidence interval; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; F, facial acne only; F+T, combined facial and truncal acne.

Other factors affecting acne-related impairment of HRQoL in facial and truncal acne

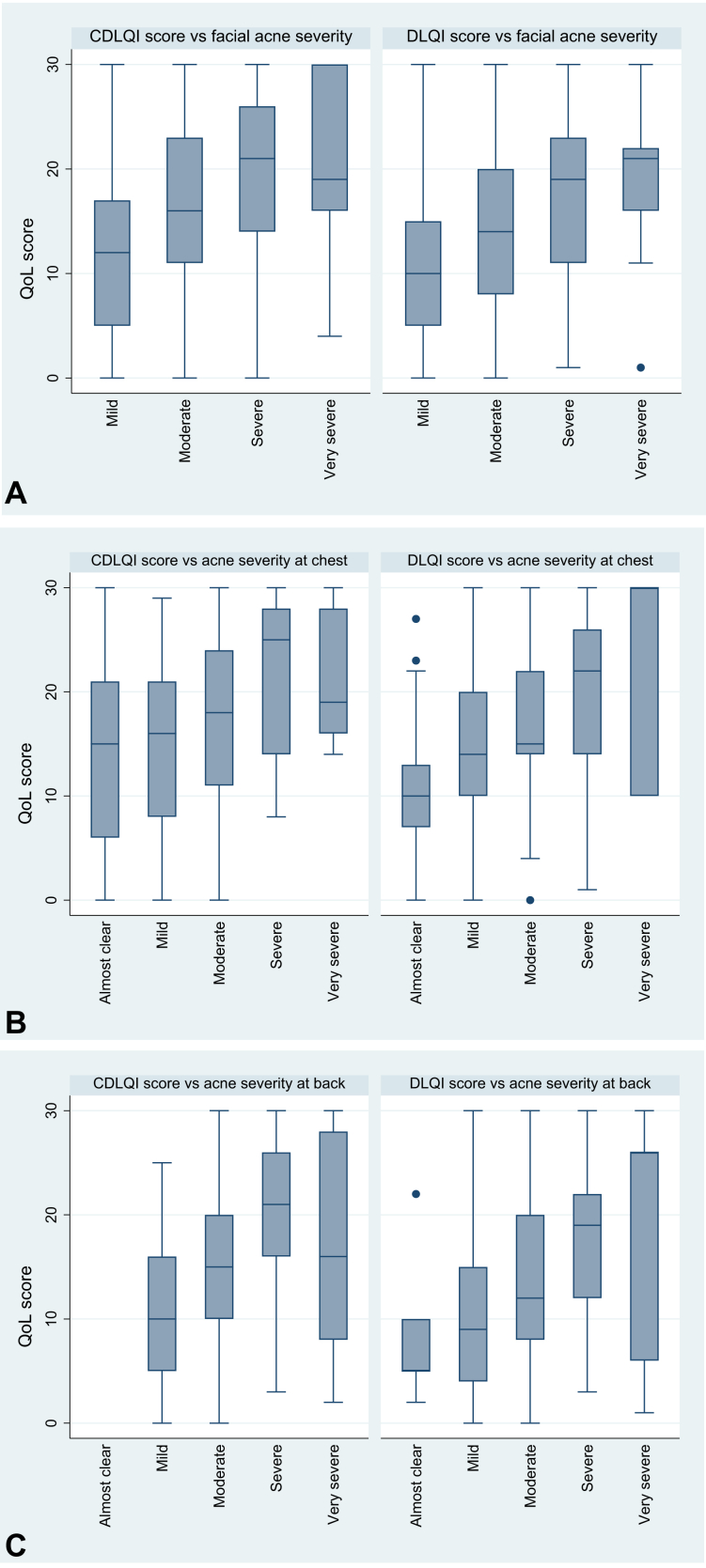

Irrespective of the acne location, the DLQI and CDLQI scores increased as the acne severity increased (Fig 2, A to C). This association remained significant in multivariate models after accounting for sex, country, type of residence, and family history of acne (Table III).

Fig 2.

A, Distribution of total HRQoL scores (per DLQI and CDLQI) by facial acne self-rated IGA score. B, Distribution of total HRQoL scores (per DLQI and CDLQI) by chest acne self-rated IGA score. C, Distribution of total HRQoL scores (per DLQI and CDLQI) by back acne self-rated IGA score. CDLQI, Children's dermatology life quality index; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; QoL, quality of life.

In stratified analysis, participants with mild-to-moderate facial acne who also had severe to very severe acne on the trunk reported significantly higher DLQI and CDLQI scores than respondents with mild-to-moderate acne on both the face and trunk (Table IV). This implied that, irrespective of the facial acne severity, severe acne of the back and/or chest was associated with additional HRQoL disability.

Table IV.

Comparison of the DLQI and CDLQI individual item scores among participants with mild or moderate facial acne who suffered from either mild-moderate versus severe-very severe acne on their back and chest

| Mild-to-moderate facial acne |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild/moderate vs severe/very severe acne on the back |

Mild/moderate vs severe/very severe acne on the chest |

|||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Crude P value∗ | Adjusted P value∗ | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Crude P value† | Adjusted P value† | |

| DLQI | 11.35 (9.6-13.1) | 16.15 (13.7-18.6) | .005 | .005 | 13.52 (11.4-15.6) | 18.04 (4.0-32.1) | .291 | .124 |

| CDLQI | 13.10 (9.7-16.5) | 18.29 (13.1-23.5) | .004 | .050 | 15.10 (11.8-18.4) | 22.22 (11.3-33.1) | .012 | .010 |

CDLQI, Children's dermatology life quality index; CI, confidence interval; DLQI, dermatology life quality index.

P value for the comparison of the DLQI (or CDLQI) score between participants with mild-to-moderate acne on the back and severe/very severe acne on the back (irrespective of acne severity on the chest), keeping facial acne constant at mild-to-moderate acne.

P value for the comparison of the DLQI (or CDLQI) score between participants with mild-to-moderate acne on the chest and severe/very severe acne on the back (irrespective of acne severity on the chest), keeping facial acne constant at mild-to-moderate acne.

Discussion

In this study, combined facial and truncal acne was found to be associated with a greater impact on HRQoL than facial acne alone. The greater reduction in self-esteem observed with higher truncal acne severity, irrespective of the facial acne severity, implied that the visibility of facial acne is not the sole factor in acne-related psychosocial distress. These results are in line with studies showing that even if the impact of facial acne on attractiveness is thought to be a primary concern, the face and trunk each contribute to overall attractiveness in both sexes.36 In addition, satisfaction with the appearance of different body parts can impact both sexual experiences and satisfaction with those experiences.37,38 Prior HRQoL studies, which primarily focused on facial acne, may therefore inadequately represent the life experience of those who also have truncal involvement.

With increasing acne severity, DLQI scores for the self-perception, physical, social, and emotional domains also increased, indicating worse HRQoL. Those who perceived their acne as more severe were more self-conscious and had increased social avoidance behaviors. Nevertheless, even milder acne can be problematic, as almost half of the respondents reporting mild facial and truncal acne in this study also reported an adverse impact on HRQoL. These findings were consistent with previous studies.29,39,40 However, several studies have shown that clinician rating of disease severity does not always correlate with patient HRQoL.41, 42, 43 In this study, the self-rating of acne severity may have included aspects of objective disease severity and aspects of personal subjective experience, supporting the current view that a complete assessment of acne should not be limited to clinician-based measures but rather also include severity as perceived by the patient and patient-reported measures of HRQoL.44

Adolescents experience considerable psychological distress as a result of having acne, which may add to the emotional and psychological challenges experienced during this period.40,45 In this study, adolescents reported avoiding swimming and practicing other sports because of embarrassment, and schoolwork was negatively affected more often than in those in their late teens or young adulthood. Psychological issues such as dissatisfaction with appearance, embarrassment, self-consciousness, and lack of self-confidence that negatively influence the desire to participate in sports and schoolwork has been documented.46,47

We used HRQoL questionnaires adapted to each age group (ie, <16 and ≥16 years); therefore, we cannot compare results across age groups. Because the burden of acne may affect distinct age groups differently, this is an important consideration when attempting comparison with other studies that included a different range of age groups.

Our study had several limitations. We excluded respondents who did not have a prescribed acne treatment in order to ensure that respondents had a confirmed diagnosis of acne (by a health care professional). In addition, the severity of acne was self-rated by the participants. Nonetheless, provision of photographs representative of severity categories should have increased the objective accuracy of the reporting. The cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for temporal evaluation of acne impact. Time and cost requirements preclude such a longitudinal trial design.

The strengths of this study include the relatively large sample sizes of the F and F+T patient populations.

In conclusion, facial and truncal acne was associated with a greater impact on HRQoL than facial acne alone. HRQoL domains including emotional well-being, everyday life activities, participation in social activities and sports, and routine acne treatment were more affected in the F+T group than in the F group. Increasing severity of truncal acne increased the adverse impact on HRQoL irrespective of the severity of the facial acne. These results implied that, as for facial acne, early effective treatment of truncal acne is important to reduce disease-related psychosocial sequelae. Our findings should encourage the development of awareness programs and treatments to address truncal and facial acne.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Tan has acted as a consultant for and/or received grants/honoraria from Bausch, Galderma, Pfizer, Almirall, Boots/Walgreens, Botanix, Cipher, Galderma, Novan, Novartis, Promius, Sun, Vichy. Dr Chavda is an employee of Galderma. Dr Beissert, Dr Cook-Bolden, Dr Harper, Dr Hebert, Dr Lain, Dr Layton, Dr Weiss, and Pr Dréno have acted as investigators and consultants for Galderma. Dr Rocha has acted as an advisor and/or speaker and received honoraria from Eucerin, Galderma, Johnson&Johnson and Leo Pharm.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Kantar Health (France) and funded by Galderma. The authors thank the study participants and their families for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Supported by Galderma.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Martin A.R., Lookingbill D.P., Botek A., Light J., Thiboutot D., Girman C.J. Health-related quality of life among patients with facial acne—assessment of a new acne-specific questionnaire. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26(5):380–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay R.J., Johns N.E., Williams H.C. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nast A., Dréno B., Bettoli V. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 1):1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Del Rosso J.Q., Bikowski J.B., Baum E. A closer look at truncal acne vulgaris: prevalence, severity, and clinical significance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(6):597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gollnick H.P., Finlay A.Y., Shear N. Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Can we define acne as a chronic disease? If so, how and when? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(5):279–284. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevalence, morbidity, and cost of dermatological diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73(5 Pt 2):395–401. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolkenstein P., Loundou A., Barrau K., Auquier P., Revuz J., Quality of Life Group of the French Society of Dermatology Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(4):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried R.G., Wechsler A. Psychological problems in the acne patient. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(4):237–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallon E., Newton J.N., Klassen A., Stewart-Brown S.L., Ryan T.J., Finlay A.Y. The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(4):672–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes L.E., Levender M.M., Fleischer A.B., Jr., Feldman S.R. Quality of life measures for acne patients. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(2):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.11.001. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn L.K., O'Neill J.L., Feldman S.R. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J.A. The impact of skin disease on the quality of life of adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2001;12(2) vii,343-353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dréno B. Assessing quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: implications for treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(2):99–106. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motley R.J., Finlay A.Y. How much disability is caused by acne? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14(3):194–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams H.C., Dellavalle R.P., Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379(9813):361–372. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta M.A., Gupta A.K. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Picardi A., Abeni D., Melchi C.F., Puddu P., Pasquini P. Psychiatric morbidity in dermatological outpatients: an issue to be recognized. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):983–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazici K., Baz K., Yazici A.E. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18(4):435–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalgard F.J., Gieler U., Tomas-Aragones L. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(4):984–991. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Misery L. Consequences of psychological distress in adolescents with acne. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(2):290–292. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan J.K. Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris: evaluating the evidence. Skin Therapy Lett. 2004;9(7):1–3. 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smithard A., Glazebrook C., Williams H.C. Acne prevalence, knowledge about acne and psychological morbidity in mid-adolescence: a community-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145(2):274–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papadopoulos L., Bor R., Legg C. Psychological factors in cutaneous disease: an overview of research. Psychol Health Med. 1999;4(2):107–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocha M.A., Bagatin E. Adult-onset acne: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:59–69. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S137794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Rosso J.Q., Stein-Gold L., Lynde C., Tanghetti E., Alexis A.F. Truncal acne: a neglected entity. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(12):205–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poli F., Auffret N., Leccia M.-T., Claudel J.-P., Dréno B. Truncal acne, what do we know? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):2241–2246. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellett S.C., Gawkrodger D.J. The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140(2):273–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadopoulos L., Walker C., Aitken D., Bor R. The relationship between body location and psychological morbidity in individuals with acne vulgaris. Psychol Health Med. 2000;5(4):431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassan J., Grogan S., Clark-Carter D., Richards H., Yates V.M. The individual health burden of acne: appearance-related distress in male and female adolescents and adults with back, chest and facial acne. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(8):1105–1118. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan J.K., Tang J., Fung K. Development and validation of a comprehensive acne severity scale. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11(6):211–216. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finlay A.Y., Khan G.K. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) — a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis-Jones M.S., Finlay A.Y. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhate K., Williams H.C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474–485. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLellan C., Frey M.P., Thiboutot D., Layton A., Chren M.M., Tan J. Development of a comprehensive quality-of-life measure for facial and torso acne. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(3):304–311. doi: 10.1177/1203475418756379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waters A., Sandhu D., Beattie P., Ezughah F., Lewis-Jones S. Severity stratification of Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) scores. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(suppl 1):121. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters M., Rhodes G., Simmons L. Contributions of the face and body to overall attractiveness. Anim Behav. 2007;73(6):937–942. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiederman M.W. Women's body image self-consciousness during physical intimacy with a partner. J Sex Res. 2000;37(1):60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woertman L., van den Brink F. Body image and female sexual functioning and behavior: a review. J Sex Res. 2012;49(2-3):184–211. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.658586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chilicka K., Maj J., Panaszek B. General quality of life of patients with acne vulgaris before and after performing selected cosmetological treatments. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1357–1361. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S131184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kilkenny M., Stathakis V., Hibbert M.E., Patton G., Caust J., Bowes G. Acne in Victorian adolescents: associations with age, gender, puberty and psychiatric symptoms. J Paediatr Child Health. 1997;33(5):430–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1997.tb01635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas C.L., Kim B., Lam J. Objective severity does not capture the impact of rosacea, acne scarring and photoaging in patients seeking laser therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):361–366. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bae J.M., Ha B., Lee H., Park C.K., Kim H.J., Park Y.M. Prevalence of common skin diseases and their associated factors among military personnel in Korea: a cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(10):1248–1254. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.10.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi N., Higaki Y., Kawamoto K., Kamo T., Shimizu S., Kawashima M. A cross-sectional analysis of quality of life in Japanese acne patients using the Japanese version of Skindex-16. J Dermatol. 2004;31(12):971–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halvorsen J.A., Braae Olesen A., Thoresen M., Holm J.Ø., Bjertness E., Dalgard F. Comparison of self-reported skin complaints with objective skin signs among adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88(6):573–577. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purvis D., Robinson E., Merry S., Watson P. Acne, anxiety, depression and suicide in teenagers: a cross-sectional survey of New Zealand secondary school students. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(12):793–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loney T., Standage M., Lewis S. Not just 'skin deep': psychosocial effects of dermatological-related social anxiety in a sample of acne patients. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):47–54. doi: 10.1177/1359105307084311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tasoula E., Gregoriou S., Chalikias J. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. Results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87(6):862–869. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]