Abstract

Background

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments are growing in popularity as alternative treatments for common skin conditions.

Objectives

To perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the tolerability and treatment response to CAM treatments in acne, atopic dermatitis (AD), and psoriasis.

Methods

PubMed/Medline and Embase databases were searched to identify eligible studies measuring the effects of CAM in acne, AD, and psoriasis. Effect size with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated using the random-effect model.

Results

The search yielded 417 articles; 40 studies met the inclusion criteria. The quantitative results of CAM treatment showed a standard mean difference (SMD) of 3.78 (95% CI [−0.01, 7.57]) and 0.58 (95% CI [−6.99, 8.15]) in the acne total lesion count, a SMD of −0.70 (95% CI [−1.19, −0.21]) in the eczema area and severity index score and a SMD of 0.94 (95% CI [−0.83, 2.71]) in the scoring of atopic dermatitis score for AD, and a SMD of 3.04 (95% CI [−0.35, 6.43]) and 5.16 (95% CI [−0.52, 10.85]) in the Psoriasis Area Severity Index score for psoriasis.

Limitations

Differences between the study designs, sample sizes, outcome measures, and treatment durations limit the generalizability of data.

Conclusions

Based on our quantitative findings we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to support the efficacy and the recommendation of CAM for acne, AD, and psoriasis.

Key words: acne vulgaris, aloe vera, atopic dermatitis, coconut oil, colloidal oatmeal, complementary alternative medicine, curcumin, eczema, green tea, honey, meta-analysis, natural ingredients, psoriasis, shea butter, sunflower seed oil, systematic review, tea tree oil, turmeric, witch hazel

Abbreviations used: AD, atopic dermatitis; AV, aloe vera; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CCO, coconut oil; GT, green tea; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; SCORAD, scoring of atopic dermatitis; SMD, standardized mean difference; SSO, sunflower seed oil; TCS, topical corticosteroid; TLC, total lesion count; TTO, tea tree oil

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Patients with common skin conditions, such as acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, report the use of complementary and alternative medicine in their treatment regimen. Yet, response to this therapy is undetermined.

-

•

This systematic review and meta-analysis will aid practitioners worldwide in counseling patients pursuing such treatment for common skin disorders.

Introduction

Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been on the rise in the past decade with an increasing number of outpatient visits to CAM professionals.1 Physicians must be made aware of the values and pitfalls of these widely used natural skincare ingredients so they can answer relevant patient inquires. The efficacy and safety of these popular ingredients have been studied with clinical trials, albeit not extensively. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to synthesize the existing data regarding the treatment efficacy of these ingredients in commonly diagnosed dermatologic conditions (acne, atopic dermatitis [AD], and psoriasis) in order to further counsel physicians in guiding patients on the use natural ingredients.

Methods

Literature search

A literature review was performed using PubMed/Medline and Embase in January 2020 to identify published randomized clinical trials and cohort studies measuring the efficacy of CAM natural skincare ingredients in the treatment of acne, AD, and psoriasis. The following search terms were used: (aloe vera or coconut oil or honey or apple cider vinegar or tea tree oil or oatmeal or sunflower seed oil or shea butter or witch hazel or green tea or lemon or turmeric) AND (acne or psoriasis or eczema or AD) AND (clinical trial).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were clinical trials or cohort studies, included at least 15 human subjects, and were published in English in an indexed journal. For the quantitative analysis, a comparison of treatment against a placebo was required. We excluded studies if they were literature reviews, case series, case reports, conference abstracts, or animal studies.

Data extraction

Two authors (V.J., P.P.) independently screened and reviewed the titles and abstracts identified in the electronic databases to establish eligibility. For records that were deemed relevant, the full-text studies were then reviewed independently by the same 2 authors (V.J., P.P.) employing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third independent author (C.W.) resolved any disagreements. After the inclusion of all relevant studies, data extraction was carried out.

Methodological quality assessment

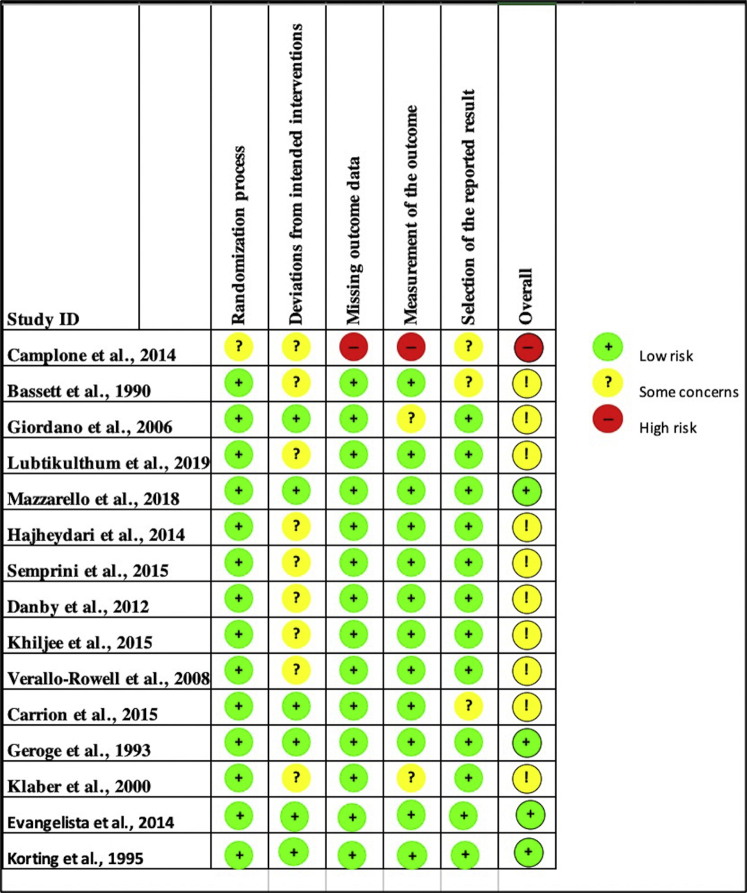

The risk-of-bias assessment was conducted using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool2 for the randomized controlled studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment score3 for the nonrandomized studies included in the systematic review, whereas Egger's test4 for publication bias was used to analyze the studies included in the meta-analysis. For the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment score studies, the bias was graded as low risk, some concerns, or high risk. Studies included within the systematic review mostly ranged from “low risk” to “some concerns,” with one “high risk study” (Fig 1, Table I).5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The Egger's test grouped by treatment showed no bias for aloe vera (AV) or turmeric. Bias was present for green tea (GT); however, further analysis through the “fill and trim” publication bias technique14 deemed no publication bias. Tea tree oil (TTO), sunflower seed oil (SSO), and colloidal oatmeal (CO) had too few studies for assessment of bias risk.

Fig 1.

Cochrane risk-of-bias summary: the authors' judgments about the studies. Studies included within the systematic review mostly ranged from low risk to some concerns except for one high-risk study per the risk-of-bias assessment.

Table I.

Newcastle-Ottawa risk assessment for non-randomized studies

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elsaie et al, 20095 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Haris et al, 20126 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Al-Waili et al, 20037 | … | … | … | Low |

| Alangari et al, 20178 | … | … | … | Low |

| Rawal et al, 20089 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Diluvio et al, 201910 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Mariano et al, 201811 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Malhi et al, 201612 | … | … | … | Some concerns |

| Lisante et al, 201728 | … | … | … | Low |

Statistical analysis methods

Analyses were conducted using R software15 version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), and forest plots were produced using the dmetar package. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and the effect size was calculated as the standardized mean difference (SMD) using Cohen's d statistic.16 Because of the significant between-study heterogeneity, the random-effect model was used for all analyses. Analyses were performed on studies measuring the same outcome variable, CAM treatment, and disease. All statistical tests and confidence intervals were two-sided, with a significance level of P < .05.

Results

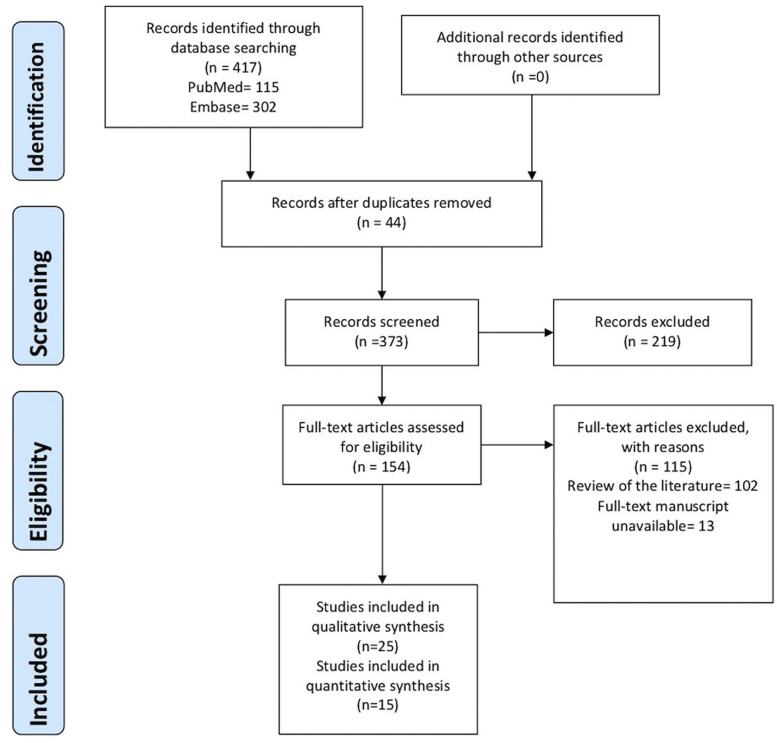

Using the aforementioned search criteria, we identified 417 articles, of which, 40 in total met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 25 were included in our qualitative analysis and 15 were included in our quantitative analysis. The publication years of the eligible articles ranged from 1990 to 2019. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow was used for the quantitative studies (Fig 2). Details regarding the included study designs, baseline characteristics, intervention, and studied variables were collected and summarized by 3 authors independently (V.J., P.P., C.W.) (Tables II and III).5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

Fig 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table II.

Characteristics of the studies included in the qualitative analysis

| Reference | Country | Age (years) | Sex (female/male) | Study design | Disease | Variable studied | Treatment ingredient | Control ingredient | n total | n treatment total | n controls total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bassett et al, 199017 | Australia | Range: 12-35 Mean: 19.7 |

60/64∗ (before dropout) | Single-blind RCT | Acne | Total number of inflamed lesions (superficial and deep) as well as noninflamed lesions (open and closed comedones) Assessment of skin tolerance |

TTO | BP | 119 | 58 | 61 |

| Mazzarello et al, 201818 | Italy | Range: 14-34 | 41/19 | Single-center, randomized, double-blinded,comparative study | Acne | TLC, ASI | TTO-PTAC, ERC | Vehicle gel | 60 | PTAC-20, ERC-20 | 20 |

| Lubtikulthum et al, 201919 | Thailand | Mean (treatment): 21.79 ± 2.238 Mean (control): 21.89 ± 2.153 |

47/27 | Observer-blinded, noninferiority randomized controlled study | Acne | TLC, adherence, porphyrin counts, DLQI, satisfaction, side effects | TTO | BP | 74 | 38 | 36 |

| Malhi et al, 201612 | Australia | Range: 16-39 Mean: 26 |

9/5 | Open-label, uncontrolled phase II pilot study | Acne | TLC | TTO | None | 14 | 14 | 0 |

| Elsaie et al, 20095 | Egypt | Range: 15-36 | 14/6 | Open-label, prospective cohort study | Acne | TLC, SI | GT | None | 20 | 20 | 0 |

| Hajheydari et al, 201420 | Iran | Range (treatment):11-32 Range (Control): 14-37 Mean (treatment): 22.33 ± 4.82 Mean (control): 24.70 ± 5.56 |

60/0 | Randomized (simple-random sampling), double-blind, prospective trial | Acne | TLC, ASI | TR/AVG | TR/vehicle | 60 | 30 | 30 |

| Haris et al, 20126 | India | Range: 15-38 | 12/9 | Open, single centric, non-comparative clinical trial | Acne | Acne score, papule count, pustule count and skin sebum Subject self-assessment of satisfaction |

AVCO | None | 21 | 21 | 0 |

| Al-Waili et al, 20037 | United Arab Emirates | Range: 5-16 | 4/17 | Patient-blinded, partially controlled study | AD | Erythema, scaling, lichenification, excoriation, indurations, oozing and itching on a 0-4 points scale | Honey, OO and beeswax mixture | TCS | 21 | 10 | 11 |

| Semprini et al, 201521 | New Zealand | Range: 16-40∗ Mean: 21.2 ± 5.8∗ |

N/A | Single-blind RCT | Acne | IGA, mean lesion count (Leeds revised acne grading system), VAS, DLQI | KH | Protex soap: triclocarban-based antibacterial soap | 106 | 68 | 67 |

| Alangari et al, 20178 | Saudi Arabia | Mean: 33 ± 10 | 8/6 | Proof-of-concept, open-label, split-treatment pilot study | AD | TIS Staphylococci and enterotoxin production via skin swab Interleukin release via enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

MH | No treatment | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Danby et al 201222 | UK | 18+ Mean Cohort 1 34 ± 4.0 |

14/5 | Two randomized forearm-controlled mechanistic studies | AD | Stratum corneum integrity and cohesion, intercorneocyte cohesion, moisturization, skin-surface pH, and erythema | SSO | OO | 19 | Cohort 2 (SSO+OO): 12 | Cohort 1 (OO): 7 |

| Khiljee et al, 201523 | Pakistan | 18+ | N/A | Double-blind RCT, comparative study | AD | Degree of erythema, edema, scaling, itching and lichenification | Indian penny wort, walnut and turmeric | Prepared without plant extracts for the 3 formulations of microemulsion, gel, ointment | 360 | 270 | 90 |

| Korting et al, 199524 | Germany | Range: 18-62 Mean: 32 |

58/12 | Double-blind, randomized, split-body, paired trial | AD | Itching, erythema and scaling (basic criteria) as well as for edema, papules, pustules, exudation, lichenification, excoriation and fissures (minor criteria) according to a 4-point scale | Hamamelis distillate | Vehicle cream or TCS | 72 | 72 | 36 vehicle cream, 36 TCS |

| Rawal et al, 20089 | India | Range: 12-80 Mean: 39.04 |

69/50 | Clinical trial | AD | Change in symptom score: erythema, scaling (crusting), thickening, and itching | Curcumin-Herbavate cream | None | 119 | 119 | 0 |

| Verallo-Rowell et al, 200825 | Philippines | Range (VCO): 29-35 Range (VOO): 21-39 Mean (VCO): 32 ± 3 Mean (VOO): 31 ± 4 |

25/27 | Double-blind, RCT | AD | SCORAD, O-SSI | VCO | VOO | 52 | 26 | 26 |

| Evangelista et al, 201426 | Philippines | Range (VCO): 3.84-5.55 Range (Mineral oil): 3.43-4.85 Mean (VCO): 4.69 Mean (Mineral Oil): 4.14 |

50/47 | Double-blind RCT | AD | SCORAD, TEWL, skin capacitance | VCO | Mineral oil | 117 | 59 | 58 |

| Camplone et al, 200427 | Italy | <14 | 128/134 + 1 not known | RCT | AD | Physician judgment, PT compliance with skin care products | CO | None | 263 | 5 groups: Colloid: 55, Derm: 29 Fluid: 75 Milk: 37 Oil: 67 |

0 |

| Lisante et al, 201728 | USA | Range: 10-80; 8-67 Mean: 32.9 ± 22.7; 27.1 ± 20.6 |

23/6; 18/12 | Two Separate single-center, single-arm clinical trial | AD | Study 1: EASI, Investigators' Global Atopic Dermatitis Assessment, VAS Study 2: EASI, Patient-reported itch severity |

CO | None | 30; 29 | 30;29 | 0 |

| Diluvio et al, 201910 | Italy | Range: 3-17 Mean: 9 |

18/12 | Clinical trial | AD | IGA, EASI, Itch severity, IDQOL | Mix of CO, avenanthramides, SB, and oat oil | None | 30 | 30 | 0 |

| Giordano et al, 200629 | France | Range: 6 months-12 years Mean: 4 years |

N/A | Multicenter RCT | AD | SCORAD, CDLQI | Shea Butter-Exomega®milk | Cleansing bar alone | 76 | 37 | 39 |

| Al-Waili et al, 20037 | United Arab Emirates | Range: 20-60 Mean: 32 |

4/14 | Patient-blinded, partially controlled study | Psoriasis | Redness, scaling, Thickening, and itching, on a 0-4 points scale | Honey, OO and beeswax mixture | TCS | 18 | 8 | 10 |

| Carrion et al, 201530 | Spain | Mean: 41.3 ± 12.0 | 8/13 | Phase IV, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot clinical trial | Psoriasis | BSA, severity signs total score, PGA, PASI | VLST | Curcuma extract with VLRT | 21 | 10 | 11 |

| George et al, 199331 | UK | Range: 18-68 | 16/13 | Single-blind, randomized controlled (half-body) study | Psoriasis | Mean psoriasis severity scores | PUVA + CO | UVB + CO | 29 | 14 | 15 |

| McKinnon and Klaber, 200032 | UK | Mean (treatment): 45.8 ± 15.6 Mean (control): 44.7 ± 16.1 |

228/247 | Multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label design | Psoriasis | Extent of scalp psoriasis estimated on 6-point scale | CCO-Calcipotriol scalp solution | Coal tar-based solution | 475 | 238 | 237 |

| Mariano et al, 201811 | Italy | Range: 18-65 | N/A | Prospective multicenter open study | Psoriasis | Clinical and patients' evaluation of scalp itching, erythema, and desquamation | Honeydew Honey-Mellis Cap shampoo | None | 30 | 30 | 0 |

AD, Atopic dermatitis; ASI, acne severity index; AVCO, activated virgin coconut oil acne gel; AVG, aloe vera gel; BP, benzoyl peroxide; BSA, body surface area affected; CCO, coconut oil; CDLQI, children's dermatology life quality index; CO, colloidal oatmeal; DLQI, dermatology life quality index; EASI, eczema area and severity index composite score; ERC, 3% erythromycin cream; GT, green tea; IDQOL, infant's dermatitis quality of life index; IGA, investigator's global assessment for acne; KH, kanuka honey; MH, manuka honey; N/A, not applicable; OO, olive oil; O-SSI, objective-SCORAD severity index; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; PGA, physician global assessment; PT, patient; PTAC, propolis, tea tree oil, and aloe vera cream; PUVA, photochemotherapy; RCT, randomized clinical trial; SB, shea butter extract; SCORAD, severity scoring of atopic dermatitis; SH, skin hydration; SI, severity index; SSO, sunflower seed oil; TCS, topical corticosteroid; TEWL, transepidermal water loss; TIS, 3 item severity score including erythema, edema/papulation, and excoriation; TLC, total lesion count reduction; TR, tretinoin cream; TTO, tea tree oil; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; UVB, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy; VAS, visual analog score; VCO, virgin coconut oil; VLRT, real visible light phototherapy; VLST, simulated visible light phototherapy; VOO, virgin olive oil.

Sex ratio does not represent patients who dropped out of the study.

Table III.

Characteristics of the studies included in the quantitative analysis

| Reference | Country | Age (years) | Sex (female/male) | Study design | Disease | Variable studied | Treatment ingredient | Control ingredient | n total | n treatment total | n controls total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enshaieh et al, 200633 | Iran | Range: 15-25 | 47/13 | Double-blind clinical trial | Acne | TLC | TTO | Vehicle gel | 60 | 30 | 30 |

| Kwon et al, 201434 | South Korea | Mean: 25.9 ± 5.6 | 23/11∗ | Prospective double-blind randomized controlled split-face trial | Acne | TLC | TTO | LFCO | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Sharquie et al, 200635 | Iraq | Range: 14-22 Mean: 17.8 ± 3.3 |

35/25∗ | Single-blind, randomly controlled therapeutic study | Acne | TLC | GT | Control solution made of 75 mL distilled water and 25 mL ethanol | 49 | 25 | 24 |

| Sharquie et al, 200836 | Iraq | Range: 13-27 Mean: 19.5 ± 3.5 |

29/11 | Single-blind, randomly comparative therapeutic clinical trial | Acne | TLC | GT | Control solution made of 5% zinc sulfate | 40 | 20 | 20 |

| Yoon et al, 201337 | South Korea | Mean: 22.1 | 18/17 | Randomized, split-face, clinical trial | Acne | TLC | GT | Vehicle control | 35 | 17 (used the 1% GT)† 18 (used the 5% GT) |

35 |

| Lu et al, 201638 | Taiwan | Range: 25-45 | 64/0 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | Acne | TLC | GT | Placebo (cellulose) | 64 | 33 | 31 |

| Msika et al, 200839 | France | Range: 4-48 months Mean: 16 months |

41/45 | RCT, multicenter study | AD | SCORAD | SSO | TCS | 86 | 53 | 33 |

| Dwiyana et al, 201940 | Indonesia | Range: 7-12 | 13/7 | Randomized, double-blind trial | AD | SCORAD | SSO | Common moisturizer lotion | 20 | 9 | 11 |

| Lisante et al, 201713 | USA | Mean: 8.1 ± 3.96 | 49/41∗ | Randomized, double-blind, two-arm trial | AD | EASI | CO | Prescription barrier cream | 68 | 31 | 37 |

| Syed et al, 199641 | USA | Range: 18-50 Mean: 25.6 |

24/36 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled study | Psoriasis | PASI | AV | Vehicle gel containing castor and mineral oil | 60 | 30 | 30 |

| Paulsen et al, 200542 | Denmark | Range: 23-77 Median: 44 |

14/26 | Single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, rand-omized, intraindividual right/left comparison | Psoriasis | PASI | AV | Vehicle gel | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Choonhakarn et al, 201043 | Thailand | Range (treatment): 27-65; Mean: 43.4 ± 11.2 Range (control): 23-71; Mean: 44.2 ± 13.0 |

39/36 | Randomized, comparative, double-blind study | Psoriasis | PASI, DLQI | AV | TA | 75 | 37 | 38 |

| Sarafian et al, 201344 | Iran | Range: 18-60 Mean: 31.7 |

14/20 | Randomized, prospective intraindividual, right-left comparative, placebo-controlled, double-blind pilot study | Psoriasis | PASI | Turmeric | Vehicle gel | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| Shathirapathiy et al, 201545 | India | Range: 20-60 Mean (treatment): 40.81 ± 13.39 Mean (control): 32.33 ± 8.70 |

20/40 | Parallel-group RCT | Psoriasis | PASI | Turmeric | Naturopathy interventions including massage, yoga, hydro, diet therapy | 60 | 30 | 30 |

| Bahraini et al, 201846 | USA | Range (treatment): 27-35 Range (control): 29-50 |

21/9 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective clinical trial | Scalp Psoriasis | PASI | Turmeric | Placebo tonic | 73 | 15 | 15 |

AD, Atopic dermatitis; AV, aloe vera; CO, colloidal oatmeal; EASI, eczema area and severity index; GT, green tea; LFCO, lactobacillus-fermented C. obtusa; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SCORAD, severity scoring of atopic dermatitis; SSO, sunflower seed oil; TA, triamcinolone acetonide; TCS, topical corticosteroid; TLC, total lesion count reduction; TTO, tea tree oil; USA, United States of America.

Indicates that the sex ratio is not representative of patients who dropped out of the study.

Only the 1% GT group was analyzed as the treatment group in the quantitative analysis.

Quantitative analysis

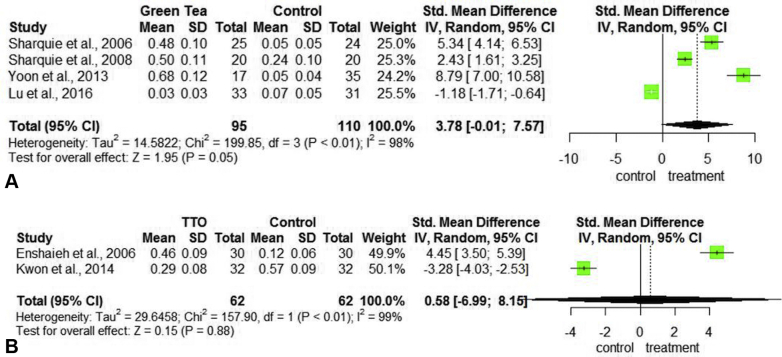

Total lesion count reduction (TLC) in acne

A total of 6 studies, including 280 acne patients, 188 treated with GT35, 36, 37, 38 and 92 patients treated with TTO12,33,34 were analyzed (Table III). The primary outcome evaluated was the reduction of the total lesion count (TLC) of pustules and papules. With GT use, the TLC was reduced by a SMD of 3.78 (95% CI [−0.01, 7.57]) (P = .05) (Fig 3, A). For the improvement of TLC with TTO, the SMD was 0.58 (95% CI [−6.99, 8.15]) (P = .88) (Fig 3, B). In both the CAM treatment groups, the TLC reduction was not statistically significant.

Fig 3.

Forest plots assessing treatments for total lesion count reduction in acne. A, Plot for green tea versus control. B, Plot for TTO versus control. CI, Confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; Std, standardized; TTO, tea tree oil.

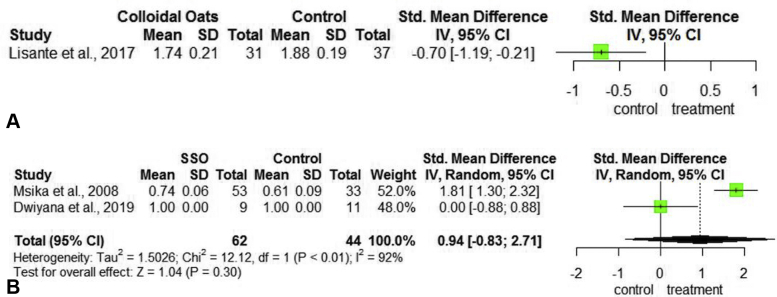

Eczema area and severity index in AD

One study that included 68 patients with AD examined the efficacy of treatment with CO13 (Table III). The primary outcome measured was improvement of the eczema area and severity index score. When compared to a barrier cream, treatment with CO proved inferior with a mean eczema area and severity index reduction of −0.70 (95% CI [−1.19, −0.21]) (Fig 4, A).

Fig 4.

Forest plots assessing the treatments for EASI and SCORAD reduction in atopic dermatitis. A, Plot for colloidal oatmeal versus control measuring EASI improvement. B, Plot for SSO versus control measuring SCORAD improvement. CI, Confidence interval; EASI, eczema area and severity index; Oats, oatmeal; SCORAD, scoring of atopic dermatitis; SD, standard deviation; SSO, sunflower seed oil; Std, standardized.

Scoring of atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) in AD

Two studies including 98 patients with AD examined the efficacy of treatment with sunflower seed oil (SSO)39,40 (Table III). The primary outcome measured was improvement of the scoring of atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) in AD score. One study found a 1.81 improvement in SCORAD (95% CI [1.30, 2.32]) while the other study found 100% reduction in SCORAD. Notably, the patients in the second study also experienced 100% reduction in SCORAD with the control- a moisturizing cream. The SMD in SCORAD was 0.94 (95% CI [−0.83, 2.71]), improvement with SSO was not statistically significant (P = .30) (Fig 4, B).

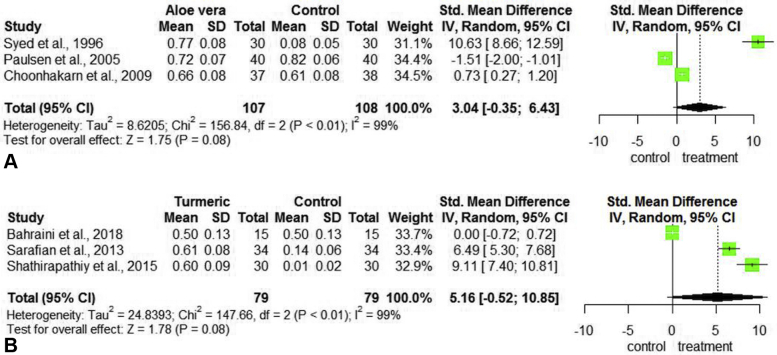

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) reduction

Three studies including 175 patients with psoriasis examined the efficacy of treatment AV on the primary outcome measure of psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score reduction41, 42, 43 (Table III). SMD with AV was 3.04 (95% CI [−0.35, 6.43]) (Fig 5, A). Three separate studies including 167 patients examined the efficacy of treatment turmeric on PASI score reduction44, 45, 46 (Table III). Analysis of these studies yielded a SMD 5.16 (95 % CI [−0.52, 10.85]) (Fig 5, B).

Fig 5.

Forest plots assessing the treatments for PASI reduction in psoriasis. A, Plot for aloe vera versus control. B, Plot for turmeric versus control. CI, Confidence interval; PASI, psoriasis area and severity index; SD, standard deviation; Std, standardized.

Qualitative results stratified by disease

Acne vulgaris

Reports of efficacy and safety with coconut oil in the treatment for acne are scarce with only one study existing in the literature. This clinical trial with virgin coconut oil treatment showed a significant reduction in inflammatory acne grading number of papules, pustules, and skin sebum.6 When combined with tretinoin cream, AV gel showed statistically significant reduction of noninflammatory, inflammatory, and total acne lesions when compared with tretinoin/vehicle. Moreover, the acne severity index was decreased to a greater extent than in the control group.20 A separate combination therapy study using 10% AV showed improvement in papular and scar lesions, with a statistically significant reduction in the erythema index of scars, acne severity index, and TLC.18 Altogether, these studies reflect that AV may be considered as an effective adjuvant treatment in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris.

Likewise, TTO treatment resulted in a statistically significant reduction of the mean total number of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions.17,19 Although TTO was associated with a slower onset of action compared with the control,17 it was associated with fewer side effects.17,19 Similarly, GT lotion treatment yielded a statistically significant reduction in the TLC and severity index.5 Lastly, kanuka honey showed little improvement of the investigator's global assessment acne score, and several participants experienced worsening acne with this treatment.21

Atopic dermatitis

The 11 studies included in the AD qualitative analysis evaluated various outcome measures. In studies examining virgin coconut oil, 1 study examined the objective-SCORAD severity index, whereas the other looked at the mean SCORAD. For both the objective-SCORAD severity index and the SCORAD, treatment with virgin coconut oil showed statistically significant improvement.25,26 Conversely, shea butter treatment did not improve the SCORAD, although xerosis and pruritus showed statistically significant improvement.29 In another study, treatment with honey led to marked improvement of severity and symptoms in 80% of patients in the treatment group and allowed reduction of topical corticosteroid (TCS) use in the control group.7 A separate study of honey showed statistically significant reductions in erythema, edema/papulation, and excoriation.8

Similarly, topical curcumin formulations including a microemulsion, a gel, and an ointment showed that microemulsion formulations were efficacious at healing symptoms of erythema and edema, whereas gel and ointments were more efficacious at pruritus and lichenification improvement, respectively.23 Of note, all turmeric formulations resulted in statistically significant decreases in symptoms.9 CO also showed statistically significant cutaneous improvement27 in areas such as epidermal thickness, skin dryness, and itching.10 Whereas SSO preserved stratum corneum integrity and improved skin hydration.22 Lastly, treatment with Hamamelis distillate cream proved inferior to TCS with regard to reductions in itching, erythema, and scaling.24

Psoriasis

A study of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis undergoing psoralen and ultraviolet A or narrow-band phototherapy ultraviolet B therapy who were pretreated with coconut oil (CCO) showed that CCO treatment failed to accelerate psoriasis clearance in comparison with non-pretreated lesions.31 However, CCO scalp solution has shown moderate statistically significant improvement in comparison with the control.32 Although this study showed improvement in the treatment group, these results may be an overestimation because of the addition of other ingredients within the calcipotriol solution.32

Similarly, a parallel study of plaque psoriasis patients showed a significant response to a honey mixture alone, whereas patients undergoing treatment with a TCS showed no relapse upon 75% reduction of the TCS doses,7 proving the efficacy of the use of honey in psoriasis. In patients with mild-to-moderate scalp psoriasis, a prospective multicenter study examining treatment with honeydew honey added to a shampoo mixture showed improvement of clinical and patient-reported parameters.11 This study concluded that a honeydew honey shampoo mixture is a proven alternative to medicated shampoos for mild-to-moderate scalp psoriasis.11

Lastly, a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of participants with moderate-to-severe psoriasis that explored the safety and efficacy of oral curcumin when used concomitantly with phototherapy established that curcumin was well tolerated and demonstrated a positive response as an adjunct to phototherapy, as 80% of subjects in both groups achieved a 90% decrease in PASI scores by the study conclusion.30

Discussion

Several CAM treatments have been described for the treatment of acne, AD, and psoriasis in patients of all ages (Table IV).7,23,37,47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87 Our meta-analysis consisted of 15 studies with a total of 280 acne patients, 174 AD patients, and 342 psoriasis patients for a combined total of 840 patients. Our systematic review analyzed data from 25 total studies; 16 were randomized clinical trials and 9 were nonrandomized studies for a combined 2249 patients (Table II). Although some information was reported in retrospective case series and case reports, we limited the data extraction to controlled clinical trials with at least 15 patients in order to review high quality studies.

Table IV.

Background information on natural ingredients studied

| Ingredient | Coconut oil47, 48, 49, 50, 51 | Aloe vera52, 53, 54, 55 | Honey7,56,57 | Turmeric23,48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62 | Colloidal oatmeal63,64 | Sunflower seed51,65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71 | Shea butter72, 73, 74, 75 | Witch hazel76, 77, 78 | Tea tree oil79, 80, 81, 82, 83 | Green tea37,84, 85, 86, 87 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | VCO is an unrefined grade of coconut oil that is harvested prior to contamination with chemical processing by-products. High levels of lauric and myristic acid within VCO are known to have antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. VCO also reduces TEWL, therefore improving barrier function in patients with AD. VCO's reputation as a moisturizing agent, wide availability, and low evidence of allergenicity make it an attractive alternative therapy for dermatologic diseases. | AV or Aloe barbadensis Mill., derived from the Liliaceae family, has been used extensively in traditional Ayurvedic medicine and other cultures. Herbal extracts or formulations of AV gel are known for their anti-inflammatory, anti-pruritic, antibacterial, and healing properties These studies prompted researchers to test the clinical efficacy of AV as a novel treatment option for both psoriasis and acne vulgaris. | Honey is a historically used CAM, most widely known for its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory therapeutic properties in addition to its ability to promote wound healing and stimulate tissue regeneration while minimizing scar size. | Curcumin, derived from the Curcuma longa Linn plant, is a polyphenol found in turmeric, known for its strong antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antiproliferative properties. Various studies, including randomized control trials (RCTs), have shown that curcumin may be used medically to treat an array of dermatologic conditions. | Colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) has served for centuries as a topical treatment for an array of skin barrier conditions, including dry skin, rashes, burns, and AD. Colloidal oatmeal extracts have been associated with induction of gene expression, including epidermal differentiation, and genes related to skin barriers such as the zonulae occludens (tight junctions) and with downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators in keratinocytes demonstrating the benefit of its clinical use. | SSO (Helianthus annus) has been extensively investigated in the treatment of xerosis and AD. SSO is defined consistent with the ratios of its fatty acid components: linoleic acid constitutes approximately 60%, whereas oleic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid, and linolenic acid are also contained in SSO. Linoleic acid in SSO is a necessary fatty acid for the maintenance of normal epidermal barrier function and helps with dermatitis resolution in infants with deficiencies. | Shea butter is extracted from the Vitellaria paradoxa tree and is composed of triglycerides with oleic, stearic, linoleic, and palmitic fatty acids, in addition to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant unsaponifiable agents including: tripterpene, tocopherol, phenols, and sterols. Furthermore, shea butter has been shown to be as effective as a ceramide-precursor in patients with AD. | Witch Hazel, derived from the plant Hamamelis virginiana, has high levels of tannins and shows antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anti-tumoral activity. Therefore, its role in the treatment of AD and other scalp disorders has been a recent point of interest among researchers and patients who commonly use witch hazel for various dermatologic conditions. | TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is an essential oil derived from the Australian plant Melaleuca alternifolia. It has broad spectrum antimicrobial activity and anti-inflammatory properties especially in acne. TTO is widely available in OTC products and marketed as a treatment for acne so studies evaluating its efficacy are important to answer patient queries. | Green tea extract, derived from the tea plant, Camellia sinensis and their polyphenolic catechins have natural healing, photoprotective, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. The major polyphenolic catechin present is (-)-EGCG, which has been found to inhibit two-stage carcinogenesis and UVB induced photocarcinogenesis. The topical application of green tea has had limitations because of stability and epidermal penetration challenges but has been shown to be an effective treatment for mild-to-moderate acne. |

AD, Atopic dermatitis; AV, aloe vera; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; EGCG, epigallocatechin-3-gallate; OTC, over the counter; SSO, sunflower seed oil; TEWL, transepidermal water loss; TTO, tea tree oil; UVB, ultraviolet B; VCO, virgin coconut oil.

Only data from the qualitative reviews showed a reduction in the primary outcome measures with CAM treatments. Within the quantitative data, there was no statistically significant difference in improvement between the CAM treatments and placebo groups in all 3 diseases examined (Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 5, B). Within the qualitative data, kanuka honey showed minimal improvement of the Investigator's Global Assessment acne score and exacerbated symptoms in others.21 Shea butter proved ineffective in improving SCORAD,29 and CCO failed to accelerate psoriasis clearance in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis undergoing psoralen and ultraviolet A or ultraviolet B therapy.31 All other CAMS did show moderate to significant improvement in patients.

Studies elsewhere have described varying degrees of successful treatment of acne,88 AD,89 and psoriasis.90 For acne, a meta-analysis found that essential oils, some including TTO, had equal or non-inferior efficacy compared with standard treatment.88 The effectiveness of these CAMs was attributed to an antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effect.88 A separate meta-analysis and systematic review determined that CAM modalities used alone or in combination with usual care may relieve AD symptoms such as pruritus and swelling anywhere from 50% to 95%, while also reducing relapse of AD.89 Our qualitative analysis agrees with these findings; however, our quantitative analysis does not. Although the CAM therapies we examined have the potential to be used safely in conjunction with standard medication regimens, our quantitative analysis deemed the CAM treatments were not superior to placebos.

Although our analysis provides important information, limitations to our study include important differences between the study design, small sample size, different outcome measures, vehicle, concentration, and treatment duration which limit the generalizability of the data for a single ingredient. Additionally, some preparations of herbal extracts consisted of combinations of different active ingredients and may have introduced over- or underestimation of treatment efficacy depending on the preparation or vehicle used.

Conclusion

In summary, the results from our quantitative analysis failed to demonstrate that the examined CAM natural treatments were superior to placebo treatments. Based on these findings, we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to support the efficacy and the recommendation of CAM for acne, AD, and psoriasis. Conversely, our systematic review found supporting evidence for the following ingredients: TTO, GT, and adjuvant use of AV for mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris; CO, honey, SSO, AV, CCO, and turmeric for AD; and honey, AV, CCO, and turmeric for psoriasis. Given our discordant data, future studies corroborating the efficacy and safety of CAM treatments in common skin conditions are warranted.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: Supported by the Research Open Access Publishing (ROAAP) Fund of the University of Illinois at Chicago and The Hispanic Center of Excellence at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Kalaaji A.N., Wahner-Roedler D.L., Sood A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients seen at the dermatology department of a tertiary care center. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gotzsche P.C. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsaie M.L., Abdelhamid M.F., Elsaaiee L.T., Emam H.M. The efficacy of topical 2% green tea lotion in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(4):358–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haris H.H., Ming K.Y., Moon K.T. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of Avoc acne gel for acne: an open, single centric, non-comparative study for 8 weeks. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2012;5:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Waili N.S. Topical application of natural honey, beeswax and olive oil mixture for atopic dermatitis or psoriasis: partially controlled, single-blinded study. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11(4):226–234. doi: 10.1016/s0965-2299(03)00120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alangari A.A., Morris K., Lwaleed B.A. Honey is potentially effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: clinical and mechanistic studies. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2017;5(2):190–199. doi: 10.1002/iid3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rawal R.C., Shah B.J., Jayaraaman A.M., Jaiswal V. Clinical evaluation of an Indian polyherbal topical formulation in the management of eczema. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(6):669–672. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diluvio L., Dattola A., Cannizzaro M.V., Franceschini C., Bianchi L. Clinical and confocal evaluation of avenanthramides-based daily cleansing and emollient cream in pediatric population affected by atopic dermatitis and xerosis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2019;154(1):32–36. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.06002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariano M., De Padova M.P., Lorenzi S., Cameli N. Clinical and videodermoscopic evaluation of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a shampoo containing ichthyol, zanthalene, mandelic acid, and honey in the treatment of scalp psoriasis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(4):296–300. doi: 10.1159/000486461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhi H.K., Tu J., Riley T.V., Kumarasinghe S.P., Hammer K.A. Tea tree oil gel for mild to moderate acne; a 12 week uncontrolled, open-label phase II pilot study. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58(3):205–210. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lisante T.A., Nunez C., Zhang P. Efficacy and safety of an over-the-counter 1% colloidal oatmeal cream in the management of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in children: a double-blind, randomized, active-controlled study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(7):659–667. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1303569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/ Accessed July 1, 2020. Available at:

- 16.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 1988. The t test for means. chapter 2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett I.B., Pannowitz D.L., Barnetson R.S. A comparative study of tea-tree oil versus benzoylperoxide in the treatment of acne. Med J Aust. 1990;153(8):455–458. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzarello V., Donadu M.G., Ferrari M. Treatment of acne with a combination of propolis, tea tree oil, and Aloe vera compared to erythromycin cream: two double-blind investigations. Clin Pharmacol. 2018;10:175–181. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S180474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubtikulthum P., Kamanamool N., Udompataikul M. A comparative study on the effectiveness of herbal extracts vs 2.5% benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(6):1767–1775. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajheydari Z., Saeedi M., Morteza-Semnani K., Soltani A. Effect of aloe vera topical gel combined with tretinoin in treatment of mild and moderate acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, prospective trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25(2):123–129. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.768328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semprini A., Braithwaite I., Corin A. Randomised controlled trial of topical kanuka honey for the treatment of acne. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e009448. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danby S.G., AlEnezi T., Sultan A. Effect of olive and sunflower seed oil on the adult skin barrier: implications for neonatal skin care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(1):42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khiljee S., Rehman N., Khiljee T., Loebenberg R., Ahmad R.S. Formulation and clinical evaluation of topical dosage forms of Indian Penny Wort, walnut and turmeric in eczema. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28(6):2001–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korting H.C., Schafer-Korting M., Klovekorn W., Klovekorn G., Martin C., Laux P. Comparative efficacy of hamamelis distillate and hydrocortisone cream in atopic eczema. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;48(6):461–465. doi: 10.1007/BF00194335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verallo-Rowell V.M., Dillague K.M., Syah-Tjundawan B.S. Novel antibacterial and emollient effects of coconut and virgin olive oils in adult atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2008;19(6):308–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evangelista M.T., Abad-Casintahan F., Lopez-Villafuerte L. The effect of topical virgin coconut oil on SCORAD index, transepidermal water loss, and skin capacitance in mild to moderate pediatric atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camplone G., Arcangeli F., Bonifazi E. The use of colloidal oatmeal products in the care of children with mild atopic dermatitis. Eur J Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;14(3):157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lisante T.A., Nunez C., Zhang P., Mathes B.M. A 1% colloidal oatmeal cream alone is effective in reducing symptoms of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis: results from two clinical studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(7):671–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giordano-Labadie F., Cambazard F., Guillet G., Combemale P., Mengeaud V. Evaluation of a new moisturizer (Exomega milk) in children with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17(2):78–81. doi: 10.1080/09546630600552216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrion-Gutierrez M., Ramirez-Bosca A., Navarro-Lopez V. Effects of curcuma extract and visible light on adults with plaque psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25(3):240–246. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George S.A., Bilsland D.J., Wainwright N.J., Ferguson J. Failure of coconut oil to accelerate psoriasis clearance in narrow-band UVB phototherapy or photochemotherapy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(3):301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKinnon M.R., Klaber C. Calcipotriol (Dovonex) scalp solution in the treatment of scalp psoriasis: comparative efficacy with 1% coal tar/1% coconut oil/0.5% salicylic acid (Capasal) shampoo, and long-term experience. J Dermatolog Treat. 2000;11(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enshaieh S., Jooya A., Siadat A.H., Iraji F. The efficacy of 5% topical tea tree oil gel in mild to moderate acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73(1):22–25. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.30646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon H.H., Yoon J.Y., Park S.Y., Min S., Suh D.H. Comparison of clinical and histological effects between lactobacillus-fermented Chamaecyparis obtusa and tea tree oil for the treatment of acne: an eight-week double-blind randomized controlled split-face study. Dermatology. 2014;229(2):102–109. doi: 10.1159/000362491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharquie K.E., Al-Turfi I.A., Al-Shimary W.M. Treatment of acne vulgaris with 2% topical tea lotion. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(1):83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharquie K.E., Noaimi A.A., Al-Salih M.M. Topical therapy of acne vulgaris using 2% tea lotion in comparison with 5% zinc sulphate solution. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(12):1757–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon J.Y., Kwon H.H., Min S.U., Thiboutot D.M., Suh D.H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves acne in humans by modulating intracellular molecular targets and inhibiting P. acnes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):429–440. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu P.H., Hsu C.H. Does supplementation with green tea extract improve acne in post-adolescent women? A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Msika P., De Belilovsky C., Piccardi N., Chebassier N., Baudouin C., Chadoutaud B. New emollient with topical corticosteroid-sparing effect in treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis: SCORAD and quality of life improvement. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(6):606–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dwiyana R.F., Darmadji H.P., Hidayah R.M. The beneficial effect of 20% sunflower seed oil cream on mild atopic dermatitis in children. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2019;11(2):100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Syed T.A., Ahmad S.A., Holt A.H., Ahmad S.A., Ahmad S.H., Afzal M. Management of psoriasis with Aloe vera extract in a hydrophilic cream: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1(4):505–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-91.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulsen E., Korsholm L., Brandrup F. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a commercial Aloe vera gel in the treatment of slight to moderate psoriasis vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(3):326–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choonhakarn C., Busaracome P., Sripanidkulchai B., Sarakarn P. A prospective, randomized clinical trial comparing topical aloe vera with 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide in mild to moderate plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(2):168–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarafian G., Afshar M., Mansouri P., Asgarpanah J., Raoufinejad K., Rajabi M. Topical turmeric microemulgel in the management of plaque psoriasis; a clinical evaluation. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14(3):865–876. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shathirapathiy G., Nair P.M., Hyndavi S. Effect of starch-fortified turmeric bath on psoriasis: a parallel randomised controlled trial. Altern Complement Ther. 2015;20(3-4):125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bahraini P., Rajabi M., Mansouri P., Sarafian G., Chalangari R., Azizian Z. Turmeric tonic as a treatment in scalp psoriasis: a randomized placebo-control clinical trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(3):461–466. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghani N.A.A., Channip A.A., Chok Hwee Hwa P., Ja'afar F., Yasin H.M., Usman A. Physicochemical properties, antioxidant capacities, and metal contents of virgin coconut oil produced by wet and dry processes. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6(5):1298–1306. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabara J.J., Swieczkowski D.M., Conley A.J., Truant J.P. Fatty acids and derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972;2(1):23–28. doi: 10.1128/aac.2.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang W.C., Tsai T.H., Chuang L.T., Li Y.Y., Zouboulis C.C., Tsai P.J. Anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of capric acid against Propionibacterium acnes: a comparative study with lauric acid. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;73(3):232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nangia S., Paul V.K., Deorari A.K., Sreenivas V., Agarwal R., Chawla D. Topical oil application and trans-epidermal water loss in preterm very low birth weight infants-a randomized trial. J Trop Pediatr. 2015;61(6):414–420. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmv049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darmstadt G.L., Saha S.K., Ahmed A.S. Effect of skin barrier therapy on neonatal mortality rates in preterm infants in Bangladesh: a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):522–529. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Athiban P.P., Borthakur B.J., Ganesan S., Swathika B. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of Aloe vera and its effectiveness in decontaminating gutta percha cones. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15(3):246–248. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.97949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Habeeb F., Stables G., Bradbury F. The inner gel component of Aloe vera suppresses bacterial-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines from human immune cells. Methods. 2007;42(4):388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chithra P., Sajithlal G.B., Chandrakasan G. Influence of aloe vera on the healing of dermal wounds in diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;59(3):195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finberg M.J., Muntingh G.L., van Rensburg C.E. A comparison of the leaf gel extracts of Aloe ferox and Aloe vera in the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis in Balb/c mice. Inflammopharmacology. 2015;23(6):337–341. doi: 10.1007/s10787-015-0251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hixon K.R., Klein R.C., Eberlin C.T. A critical review and perspective of honey in tissue engineering and clinical wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2019;8(8):403–415. doi: 10.1089/wound.2018.0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niaz K., Maqbool F., Bahadar H., Abdollahi M. Health benefits of manuka honey as an essential constituent for tissue regeneration. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18(10):881–892. doi: 10.2174/1389200218666170911152240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mirzaei H., Shakeri A., Rashidi B., Jalili A., Banikazemi Z., Sahebkar A. Phytosomal curcumin: a review of pharmacokinetic, experimental and clinical studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;85:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Antiga E., Bonciolini V., Volpi W., Del Bianco E., Caproni M. Oral curcumin (Meriva) is effective as an adjuvant treatment and is able to reduce il-22 serum levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:283634. doi: 10.1155/2015/283634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jagetia G.C., Aggarwal B.B. “Spicing up” of the immune system by curcumin. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27(1):19–35. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vaughn A.R., Branum A., Sivamani R.K. Effects of turmeric (Curcuma longa) on skin health: a systematic review of the clinical evidence. Phytother Res. 2016;30(8):1243–1264. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bilia A.R., Bergonzi M.C., Isacchi B., Antiga E., Caproni M. Curcumin nanoparticles potentiate therapeutic effectiveness of acitrein in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients and control serum cholesterol levels. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2018;70(7):919–928. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ilnytska O., Kaur S., Chon S. Colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) improves skin barrier through multi-therapy activity. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reynertson K.A., Garay M., Nebus J. Anti-inflammatory activities of colloidal oatmeal (Avena sativa) contribute to the effectiveness of oats in treatment of itch associated with dry, irritated skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(1):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Darmstadt G.L., Saha S.K., Ahmed A.S. Effect of topical treatment with skin barrier-enhancing emollients on nosocomial infections in preterm infants in Bangladesh: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Darmstadt G.L., Badrawi N., Law P.A. Topically applied sunflower seed oil prevents invasive bacterial infections in preterm infants in Egypt: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(8):719–725. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000133047.50836.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanti V., Grande C., Stroux A., Buhrer C., Blume-Peytavi U., Bartels N.G. Influence of sunflower seed oil on the skin barrier function of preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Dermatology. 2014;229(3):230–239. doi: 10.1159/000363380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Simpson E.L., Chalmers J.R., Hanifin J.M. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karagounis T.K., Gittler J.K., Rotemberg V., Morel K.D. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/pde.13621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elias P.M., Brown B.E., Ziboh V.A. The permeability barrier in essential fatty acid deficiency: evidence for a direct role for linoleic acid in barrier function. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;74(4):230–233. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12541775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Friedman Z., Shochat S.J., Maisels M.J., Marks K.H., Lamberth E.L., Jr. Correction of essential fatty acid deficiency in newborn infants by cutaneous application of sunflower-seed oil. Pediatrics. 1976;58(5):650–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maranz S., Wiesman Z., Garti N. Phenolic constituents of shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) kernels. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(21):6268–6273. doi: 10.1021/jf034687t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maranz S., Wiesman Z. Influence of climate on the tocopherol content of shea butter. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(10):2934–2937. doi: 10.1021/jf035194r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lin T.K., Zhong L., Santiago J.L. Anti-inflammatory and skin barrier repair effects of topical application of some plant oils. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):70. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hon K.L., Tsang Y.C., Pong N.H. Patient acceptability, efficacy, and skin biophysiology of a cream and cleanser containing lipid complex with shea butter extract versus a ceramide product for eczema. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(5):417–425. doi: 10.12809/hkmj144472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rasooly R., Molnar A., Choi H.Y., Do P., Racicot K., Apostolidis E. In-vitro inhibition of staphylococcal pathogenesis by witch-hazel and green tea extracts. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019;8(4):244. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8040244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Solis-Arevalo K.K., Garza-Gonzalez M.T., Lopez-Calderon H.D., Solis-Rojas C., Arevalo-Nino K. Electrospun membranes based on schizophyllan-pvoh and hamamelis virginiana extract: antimicrobial activity against microorganisms of medical importance. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2019;18(4):522–527. doi: 10.1109/TNB.2019.2924166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lizarraga D., Tourino S., Reyes-Zurita F.J. Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) fractions and the importance of gallate moieties--electron transfer capacities in their antitumoral properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(24):11675–11682. doi: 10.1021/jf802345x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thosar N., Basak S., Bahadure R.N., Rajurkar M. Antimicrobial efficacy of five essential oils against oral pathogens: an in vitro study. Eur J Dent. 2013;7(suppl 1):S071–S077. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.119078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Atkinson N., Brice H.E. Antibacterial substances produced by flowering plants. II. The antibacterial action of essential oils from some Australian plants. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1955;33(5):547–554. doi: 10.1038/icb.1955.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhong W., Chi G., Jiang L. p-Cymene modulates in vitro and in vivo cytokine production by inhibiting MAPK and NF-kappaB activation. Inflammation. 2013;36(3):529–537. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9574-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maruyama N., Sekimoto Y., Ishibashi H. Suppression of neutrophil accumulation in mice by cutaneous application of geranium essential oil. J Inflamm (Lond) 2005;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hammer K.A. Treatment of acne with tea tree oil (melaleuca) products: a review of efficacy, tolerability and potential modes of action. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45(2):106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liao S. The medicinal action of androgens and green tea epigallocatechin gallate. Hong Kong Med J. 2001;7(4):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu Y.P., Lou Y.R., Xie J.G. Topical applications of caffeine or (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) inhibit carcinogenesis and selectively increase apoptosis in UVB-induced skin tumors in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(19):12455–12460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182429899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yusuf N., Irby C., Katiyar S.K., Elmets C.A. Photoprotective effects of green tea polyphenols. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dvorakova K., Dorr R.T., Valcic S., Timmermann B., Alberts D.S. Pharmacokinetics of the green tea derivative, EGCG, by the topical route of administration in mouse and human skin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43(4):331–335. doi: 10.1007/s002800050903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deyno S., Mtewa A.G., Abebe A. Essential oils as topical anti-infective agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;47:102224. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu C.L., Liu X.H., Stub T. Complementary and alternative medicine for treatment of atopic eczema in children under 14 years old: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gamret A.C., Price A., Fertig R.M., Lev-Tov H., Nichols A.J. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies for psoriasis: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1330–1337. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]