Abstract

Introduction

Skin diseases have a significant global impact on quality of life, mental health, and loss of income. The burden of dermatologic conditions and its relationship with socioeconomic status in Asia is currently not well understood.

Methods

We selected Global Burden of Disease Study datasets to analyze disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 50 Asian countries, including Central Asia, northern Asia, eastern Asia, western Asia, southeastern Asia, and southern Asia, between 1990 and 2017. We compared DALYs to the socioeconomic status using the sociodemographic index and gross domestic product per capita of a country. Statistical analysis was performed using Pearson's correlation.

Results

Some countries had higher or lower than expected age-standardized DALY rates of skin diseases. Asian countries, especially high-income countries, had a high burden of inflammatory dermatoses, including acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, decubitus ulcers, psoriasis, pruritus, and seborrheic dermatitis. The burden of infectious dermatoses was greater in low-income Asian countries. The burden of skin cancer in Asia was relatively low.

Conclusion

There is a high burden of skin disease, especially inflammatory conditions, in Asian countries, but the burden of individual dermatoses in Asia varies by country and socioeconomic status. DALYs can potentially serve as a purposeful measure for directing resources to improve the burden of skin disease in Asia.

Key words: acne, age-standardized prevalence rates, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, basal cell carcinoma, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) database, global medicine, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, infectious disease, itch, leishmaniasis, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), pruritus, psoriasis, scabies, skin cancer, socioeconomic status, squamous cell carcinoma, syphilis, tuberculosis, urticaria, viral skin diseases

Abbreviations used: AA, Alopecia areata; DALYs, disability-adjusted life years; GBD, Global Burden of Disease; GDP, gross domestic product; NMSC, nonmelanoma skin cancer; SDI, sociodemographic index

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Understanding the regional impact of dermatologic disease is critical to developing a concerted and sustained global effort toward reducing this burden.

-

•

A relationship exists between socioeconomic status, geographic location, and certain dermatoses in Asia. Resources could be directed at countries with high disability-adjusted life years to create impactful interventions.

Introduction

Skin disease is a common health problem worldwide and a leading cause of global disease burden. Disability associated with skin conditions is significant and affects people of all ages and cultures. Skin and subcutaneous diseases contributed 1.79% to the global burden of disease (GBD) and were the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden and disability in 2013.1

Disease burden can be estimated using the measure of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is the sum of years lost due to premature death and years lost due to a disability.2 Additionally, the sociodemographic index (SDI) was used to identify where countries or geographic areas are in terms of their development based on average income per person, educational attainment, and total fertility rate.3 The burden of skin disease has shown both regional and socioeconomic variations. For example, melanoma causes the greatest burden in high-income countries, such as Australia, high-income North America, central Europe, and western Europe, whereas the burden of psoriasis is the greatest in Australasia, western Europe, high-income Asia Pacific, and southern Latin America.1

Skin disease is widely prevalent throughout Asia, but the quantitative impact has not been well documented. As a result, there are few studies on the epidemiology and burden of skin disease in Asia. Accurate information about the burden of dermatologic conditions can help develop and optimize interventions required to minimize the morbidity and economic impact for those affected. This observational study compares the relationship between the burden of skin disease and socioeconomic status of 50 Asian countries in 2017 and examines the annual rate of change in common skin diseases between 1990 and 2017.

Methods

Data source

The World Bank database of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was used to measure the socioeconomic status of the countries in 2017.4 Information on DALYs of the most common dermatoses was obtained from the GBD study 2017 datasets.5 The GBD database allows the comparison of the magnitude of diseases, injuries, and risk factors across countries, regions, sexes, and age groups from 1990 to the present day for more than 350 diseases in 195 countries.6 The GBD project is led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington and is a global collaboration with over 145 countries and 3600 researchers worldwide.6 An in-depth protocol is available from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation on how data are obtained, incorporated, calculated, and published in the GBD study.7

Study design

A cross-sectional analysis between 1990 and 2017 of all the Asian countries was performed. The countries included in the definition of Asia are those in Central Asia, northern Asia, eastern Asia, western Asia, southeastern Asia, and southern Asia. The country demographics, including population size, GDP per capita, fertility rate, educational attainment, life expectancy, and mortality under the age of 1 and 5 years are provided (Table I).8

Table I.

Asian country profiles∗

| Country | Population | Per capita GDP | Fertility rate | Educational attainment (Years) | Female life expectancy (Years) | Male life expectancy (Years) | Mortality under 5 | Mortality under 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 32.9M | $1337 | 6.0 | 2.7 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 54.1 | 44.1 |

| Armenia | 3.0M | $8505 | 1.6 | 12.1 | 78.7 | 72.4 | 9.6 | 8.1 |

| Azerbaijan | 10.2M | $16349 | 2.0 | 11.3 | 74.7 | 67.2 | 35.2 | 30.9 |

| Bahrain | 1.5M | $44399 | 2.0 | 7.7 | 80.4 | 78.8 | 7.3 | 5.9 |

| Bangladesh | 157M | $3522 | 2.0 | 5.1 | 74.6 | 71.8 | 33.1 | 27.7 |

| Bhutan | 957.4K | $7938 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 76.1 | 72.4 | 29.3 | 25.0 |

| Brunei | 432.5K | $66,999 | 1.9 | 11.6 | 77.5 | 73.4 | 9.0 | 7.7 |

| Cambodia | 16.1M | $3535 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 72.7 | 66.8 | 31.5 | 26.5 |

| China | 1.4B | $15085 | 1.5 | 10.3 | 79.9 | 74.5 | 12.0 | 9.7 |

| Cyprus | 1.3M | $31531 | 1.0 | 13.2 | 85.2 | 78.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 |

| Georgia | 3.7M | $9486 | 2.0 | 12.8 | 77.3 | 68.4 | 11.1 | 9.5 |

| India | 1.4B | $6265 | 2.1 | 7.0 | 70.2 | 67.8 | 42.4 | 36.0 |

| Indonesia | 258.1M | $10907 | 2.0 | 8.3 | 73.9 | 69.2 | 26.0 | 21.7 |

| Iran | 82.2M | $17519 | 1.7 | 8.8 | 79.4 | 75.5 | 14.4 | 12.3 |

| Iraq | 43.3M | $14427 | 3.8 | 7.1 | 78.8 | 74.8 | 25.1 | 19.3 |

| Israel | 8.9M | $33068 | 2.9 | 12.9 | 84.6 | 81.3 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| Japan | 128.4M | $37654 | 1.3 | 13.3 | 87.2 | 81.1 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| Jordan | 10.6M | $9916 | 3.1 | 10.8 | 81.1 | 77.9 | 14.4 | 12.3 |

| Kazakhstan | 17.9M | $23781 | 2.4 | 11.4 | 76.4 | 67.5 | 14.1 | 11.3 |

| Kuwait | 4.3M | $62589 | 1.4 | 8.8 | 87.2 | 80.7 | 7.8 | 6.6 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 6.4M | $3283 | 2.8 | 11.9 | 76.3 | 69.1 | 20.1 | 17.1 |

| Laos | 7.0M | $6306 | 2.9 | 6.3 | 70.4 | 65.1 | 57.5 | 49.1 |

| Lebanon | 8.5M | $14678 | 2.4 | 11.8 | 80.0 | 75.8 | 8.1 | 7.0 |

| Malaysia | 30.6M | $25747 | 2.0 | 9.6 | 77.3 | 72.4 | 7.2 | 5.8 |

| Maldives | 458.6K | $14887 | 1.9 | 7.1 | 83.4 | 79.9 | 7.7 | 6.1 |

| Mongolia | 3.3M | $11329 | 2.7 | 10.1 | 73.7 | 64.5 | 25.7 | 21.7 |

| Myanmar | 52.8M | $5816 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 72.2 | 64.9 | 44.3 | 37.0 |

| Nepal | 29.9M | $2363 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 73.3 | 68.7 | 31.4 | 27.2 |

| North Korea | 25.7M | $1660 | 1.3 | 8.4 | 75.1 | 68.7 | 22.7 | 18.4 |

| Oman | 4.5M | $38321 | 2.5 | 7.4 | 79.5 | 75.5 | 10.6 | 8.5 |

| Pakistan | 214.3M | $4913 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 67.5 | 66.4 | 58.2 | 49.0 |

| Palestine | 4.9M | $3688 | 3.5 | 9.8 | 78.0 | 75.6 | 13.6 | 11.3 |

| Philippines | 103.5M | $7426 | 3.1 | 9.6 | 73.1 | 66.6 | 26.6 | 19.9 |

| Qatar | 2.7M | $104196 | 2.0 | 8.7 | 81.7 | 79.6 | 7.4 | 6.1 |

| Russia | 146.2M | $24427 | 1.6 | 12.5 | 77.2 | 66.8 | 7.4 | 6.0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 34.4M | $48709 | 1.7 | 8.2 | 79.4 | 75.3 | 7.9 | 6.5 |

| Singapore | 5.6M | $78723 | 1.3 | 11.6 | 87.6 | 81.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| South Korea | 52.7M | $35945 | 1.2 | 13.3 | 85.5 | 79.5 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Sri Lanka | 21.6M | $11567 | 1.8 | 9.3 | 81.1 | 73.9 | 8.5 | 7.2 |

| Syria | 18.1M | $4708 | 2.2 | 8.3 | 75.0 | 65.5 | 19.7 | 8.8 |

| Taiwan | 23.6M | $42189 | 1.0 | 12.8 | 83.3 | 76.8 | 4.7 | 3.8 |

| Tajikistan | 9.2M | $2759 | 3.5 | 10.7 | 73.3 | 67.7 | 46.9 | 38.1 |

| Thailand | 70.6M | $15647 | 1.2 | 9.1 | 82.0 | 74.3 | 8.7 | 6.5 |

| Timor-Leste | 1.3M | $2715 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 73.0 | 68.9 | 35.7 | 28.3 |

| Turkey | 80.5M | $22903 | 1.8 | 10.1 | 83.1 | 75.2 | 14.2 | 11.5 |

| Turkmenistan | 5.0M | $18154 | 2.8 | 10.7 | 73.9 | 66.5 | 29.1 | 24.0 |

| United Arab Emirates | 9.7M | $63839 | 1.3 | 9.7 | 77.0 | 71.7 | 7.1 | 5.6 |

| Uzbekistan | 32.2M | $6908 | 2.4 | 11.4 | 73.8 | 67.1 | 23.8 | 19.7 |

| Vietnam | 96.1M | $6143 | 1.9 | 8.6 | 79.2 | 70.0 | 13.1 | 10.4 |

| Yemen | 30.4M | $2093 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 70.3 | 66.0 | 45.9 | 37.1 |

GDP, Gross domestic product.

All the data are from 2017. Total fertility rate is the average number of children a woman is expected to deliver over her lifetime. Mortality rates under ages 1 and 5 years are measured as the number of deaths per 1000 live births.

Statistical analysis

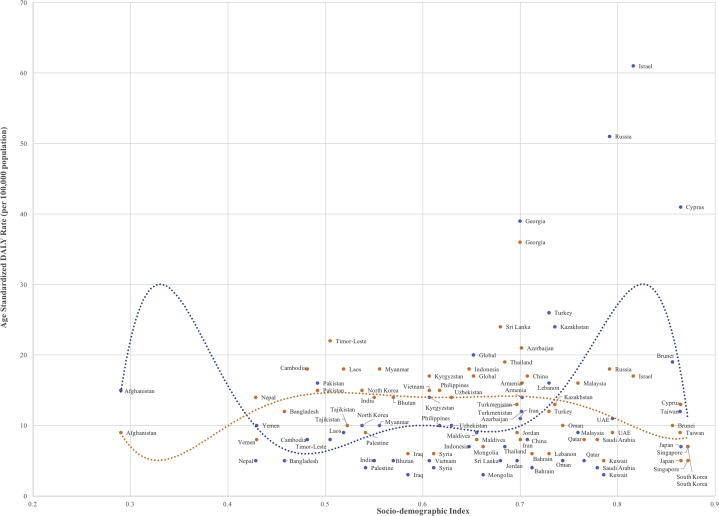

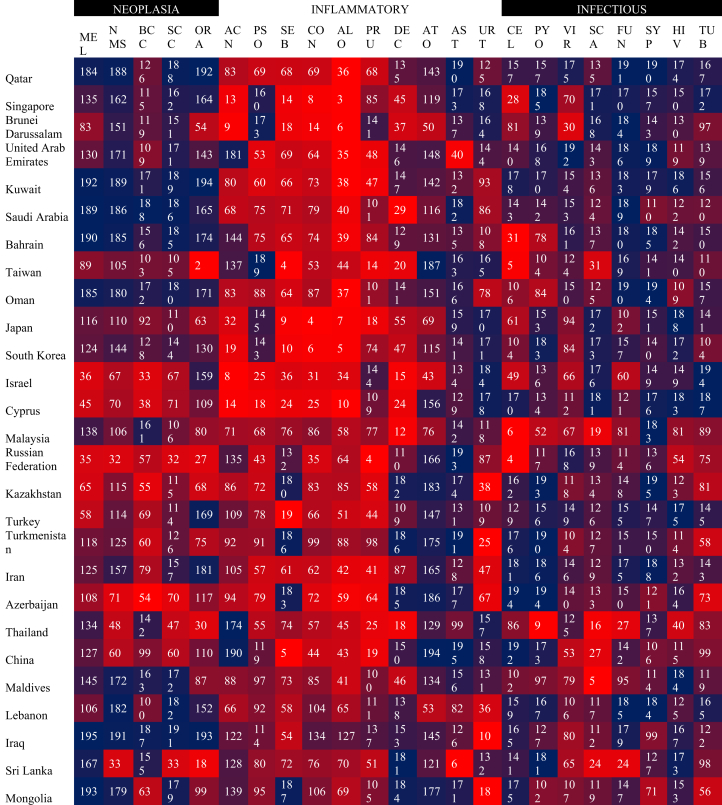

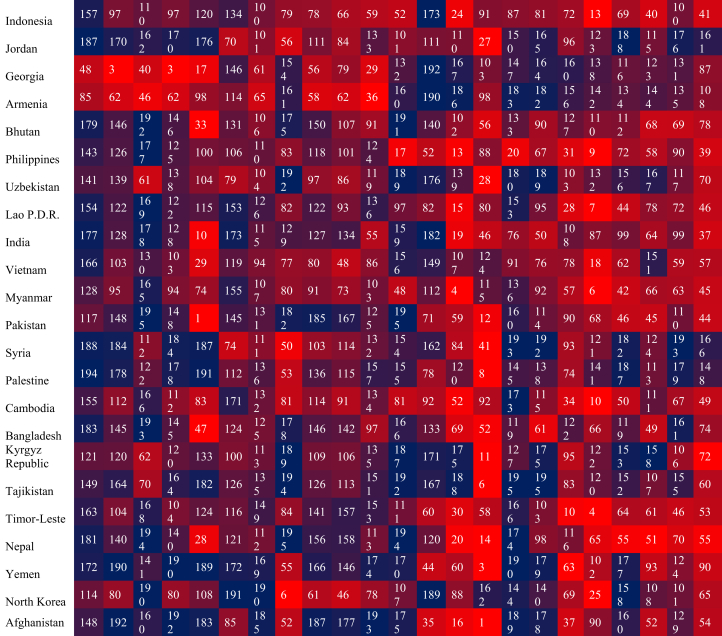

We compared the age-standardized DALY rates per 100,000 for skin and subcutaneous diseases, melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) to the absolute SDI values of 50 Asian countries in 2017 (Figs 1 and 2). We also measured the annual percentage change in skin and subcutaneous diseases, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, lip and oral cancer, contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, acne vulgaris, alopecia areata (AA), pruritus, urticaria, decubitus ulcer, asthma, cutaneous leishmaniasis, cellulitis, pyoderma, scabies, viral skin disease, fungal skin disease, and “other skin and subcutaneous disease” (Table II). Asthma was included in our analysis to highlight the relationship with conditions, such as atopic dermatitis, which is often the first step in an atopic march leading to the development of asthma.9,10 Three broad categories were analyzed for each Asian country in a heat table: neoplastic, inflammatory, and infectious. Neoplastic diagnoses included melanoma, NMSC, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and oral/lip cancer. Inflammatory conditions included psoriasis, contact dermatitis, pruritus, AA, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, decubitus ulcer, atopic dermatitis, asthma, and urticaria. Infectious disorders included pyoderma, viral skin disease, cellulitis, scabies, fungal skin disease, leishmaniasis, syphilis, HIV, and tuberculosis. The countries were placed in order in rows from top (lowest GDP) to bottom (highest GDP), and each country was numerically ranked from 1 (red, highest DALYs in the world) to 195 (blue, lowest DALYs in the world) for each disease (Fig 3). Statistical analyses of the correlations between DALYs and GDP per capita were performed using Pearson's coefficient, r, with SPSS Statistics software version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The Asian countries were organized in the heat table by GDP per capita, from most wealthy (top row) to least wealthy (bottom row).

Fig 1.

Age-standardized DALY rates caused by skin and subcutaneous diseases by SDI for Asian countries in 2017. DALY, Disability-adjusted life years; SDI, sociodemographic index.

Fig 2.

Age-standardized DALY rates caused by melanoma (blue) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (orange) by SDI for Asian countries in 2017. DALY, Disability-adjusted life years; SDI, sociodemographic index.

Table II.

Notable top 10th percentile world rankings of Asian countries by annual percent change from 1990 to 2017 measured in DALYs per 100,000

| Disease | Asian country | World ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Skin and subcutaneous disease | Cyprus | 6 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Armenia | 4 |

| Georgia | 6 | |

| Iran | 10 | |

| Basal cell carcinoma | Taiwan | 7 |

| Sri Lanka | 8 | |

| Turkey | 9 | |

| China | 10 | |

| Vietnam | 15 | |

| Melanoma | Brunei | 4 |

| South Korea | 6 | |

| Lip and oral cancer | Taiwan | 1 |

| China | 5 | |

| Georgia | 7 | |

| Azerbaijan | 9 | |

| Pakistan | 18 | |

| Contact dermatitis | Maldives | 1 |

| Iran | 2 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 3 | |

| Oman | 4 | |

| Bangladesh | 6 | |

| Cambodia | 7 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 8 | |

| Syria | 9 | |

| Nepal | 12 | |

| China | 14 | |

| Turkey | 15 | |

| Brunei | 16 | |

| India | 18 | |

| Qatar | 20 | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Taiwan | 1 |

| South Korea | 2 | |

| Japan | 4 | |

| Maldives | 5 | |

| Brunei | 8 | |

| Singapore | 9 | |

| China | 12 | |

| Laos | 15 | |

| Psoriasis | Saudi Arabia | 1 |

| Maldives | 2 | |

| Oman | 3 | |

| Taiwan | 4 | |

| Thailand | 5 | |

| China | 6 | |

| Turkey | 7 | |

| Myanmar | 8 | |

| Sri Lanka | 9 | |

| Yemen | 11 | |

| Atopic dermatitis | Afghanistan | 1 |

| Pakistan | 20 | |

| Acne | Yemen | 2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 3 | |

| Lebanon | 6 | |

| Nepal | 7 | |

| Timor-Leste | 8 | |

| Laos | 9 | |

| Bangladesh | 10 | |

| Omen | 11 | |

| Bhutan | 12 | |

| Turkey | 13 | |

| Iraq | 14 | |

| India | 15 | |

| Jordan | 16 | |

| Qatar | 17 | |

| Cambodia | 18 | |

| Malaysia | 19 | |

| Pakistan | 20 | |

| Alopecia areata | Maldives | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | |

| Oman | 3 | |

| Iran | 4 | |

| United Arab Emirates | 6 | |

| Bhutan | 7 | |

| Cambodia | 9 | |

| Lebanon | 11 | |

| Qatar | 12 | |

| Jordan | 13 | |

| Yemen | 14 | |

| Palestine | 15 | |

| Turkmenistan | 16 | |

| Pakistan | 18 | |

| Azerbaijan | 19 | |

| Pruritus | South Korea | 1 |

| China | 2 | |

| Thailand | 4 | |

| Taiwan | 5 | |

| Maldives | 7 | |

| Iran | 8 | |

| Vietnam | 9 | |

| Singapore | 10 | |

| Turkey | 12 | |

| Bangladesh | 13 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 15 | |

| Bhutan | 16 | |

| Bahrain | 17 | |

| Urticaria | Afghanistan | 1 |

| Cyprus | 8 | |

| Pakistan | 18 | |

| Decubitus ulcer | Thailand | 2 |

| Malaysia | 3 | |

| Cambodia | 10 | |

| South Korea | 12 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 19 | |

| Asthma | Jordan | 9 |

| Lebanon | 14 | |

| Cutaneous leishmaniasis | Syria | 2 |

| Tajikistan | 4 | |

| Iraq | 5 | |

| Sri Lanka | 7 | |

| Kuwait | 9 | |

| Israel | 11 | |

| Palestine | 12 | |

| Lebanon | 13 | |

| China | 16 | |

| Georgia | 20 | |

| Cellulitis | Israel | 6 |

| Malaysia | 11 | |

| Taiwan | 12 | |

| Georgia | 15 | |

| Pyoderma | Georgia | 9 |

| Israel | 13 | |

| Armenia | 14 | |

| Scabies | Afghanistan | 3 |

| North Korea | 9 | |

| Pakistan | 15 | |

| Viral skin disease | Afghanistan | 1 |

| Pakistan | 18 | |

| Fungal skin disease | Japan | 1 |

| China | 16 | |

| Jordan | 20 | |

| Other skin and subcutaneous disease∗ | South Korea | 1 |

| China | 2 | |

| Thailand | 4 | |

| Japan | 7 | |

| Vietnam | 9 | |

| Sri Lanka | 10 | |

| India | 18 | |

| Maldives | 19 |

DALY, Disability-adjusted life years.

Encompasses dermatoses, such as bullous diseases, connective tissue diseases, and cutaneous drug reactions.

Fig 3.

Heat table with Asian countries placed in ordered in a heat table with in rows from the highest (most wealthy) to the lowest (least wealthy), and); each country was numerically ranked in the world from 1 (red, highest DALYs) to 195 (blue, lowest DALYs) for each disease in 2017. AA, Alopecia areata; ACN, acne; AST, asthma; ATO, atopic dermatitis; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CEL, cellulitis; CON, contact dermatitis; DALY, disability-adjusted life year; DEC, decubitus ulcer; FUN, fungal skin disease; MEL, melanoma; NMS, nonmelanoma skin cancer; ORA, oral/lip cancer; PRU, pruritus; PSO, psoriasis; PYO, pyoderma; SCA, scabies; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SEB, seborrheic dermatitis; SYP, syphilis; TUB, tuberculosis.; URT, urticaria; VIR, viral skin disease.

Results

Several countries, including Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Israel, and Maldives, had higher than expected age-standardized DALY rates caused by skin and subcutaneous diseases when compared to their associated SDI in 2017 (Fig 1). Syria, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan showed lower than expected age-standardized DALY rates caused by skin and subcutaneous diseases based on their associated SDI. For melanoma, Israel, Russia, Cyprus, and Georgia had higher than expected age-standardized DALY rates. Georgia, Timor-Leste, Russia, and Israel showed higher than expected age-standardized DALY rates caused by NMSC.

Among the inflammatory dermatoses, a positive correlation between DALYs and GDP per capita was seen for alopecia (0.80), contact dermatitis (0.73), acne (0.47), decubitus ulcer (0.44), psoriasis (0.42), and pruritus (0.41), whereas a negative correlation was seen for urticaria (−0.58) and asthma (−0.52) (Fig 3). Among the infectious dermatoses, there was a positive correlation between DALYs and GDP per capita for cellulitis (0.42) and a negative correlation for syphilis (−0.67), tuberculosis (−0.60), scabies (−0.46), viral skin infections (−0.46), fungal infections (−0.33), and HIV (−0.32). Only weak correlations were found between GDP per capita and DALYs for the neoplastic cutaneous disorders and atopic dermatitis.

When looking at the annual percent change in DALYs between 1990 and 2017, Cyprus was the only Asian country within the top 10th percentile globally for skin and subcutaneous diseases overall (Table II). Only 3 countries were in the top 10th percentile for increase in squamous cell carcinoma, 5 for basal cell carcinoma, and 2 for melanoma. In contrast, several Asian countries ranked at the top for the greatest annual increase in DALYs of the inflammatory dermatoses. Seventeen Asian countries were within the top 10th percentile of increase in acne, including Yemen (second), Saudi Arabia (third), Lebanon (sixth), Nepal (seventh), Timor-Leste (eighth), Laos (ninth), and Bangladesh (10th). Fifteen Asian countries were within the top 10th percentile for increase in AA, with Maldives, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Iran ranking first through fourth, respectively. The same countries were also the top 4 in the world for increase in contact dermatitis. Pruritus DALYs were also increasing in Asia, with 13 countries in the top 10th percentile. Notably, in the infectious dermatoses category, 10 Asian countries were in the top 10th percentile for increase in cutaneous leishmaniasis and 3 for scabies.

Discussion

Our analysis of GBD 2017 shows that Asian countries have a high burden of inflammatory dermatoses, including many that are frequently associated with itching (ie, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and pruritus). Literature on the burden of dermatoses associated with pruritus in Asia is lacking, with the exception of atopic dermatitis. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis has been increasing significantly in Asia in the past few decades, which has been attributed to urbanization, increased family income, better education, increased allergen exposure, and frequent bathing and soap usage.11 Future studies are warranted to further investigate the high burden of other pruritic dermatoses in this region.

Acne vulgaris was another burdensome inflammatory disease in Asia, with 17 Asian countries among the top 10th percentile globally for the annual percentage change in acne DALYs. Acne prevalence has been reported to be as high as 88% in Asia and can cause a substantial burden by negatively affecting the quality of life and mood of those affected, including an increased risk of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 In 2010, eastern Asia, southern Asia, and western Europe were regions reported to have the highest prevalence of acne vulgaris in the world in the 15-19–years age group among their respective unadjusted age populations.18 Cultural differences regarding skin care practices may contribute to a variable burden of acne between different ethnic groups and countries. For example, a common belief held by individuals in southern Asia is that poor hygiene and diet are major components of the pathogenesis of acne, and they self-treat by excessive washing and scrubbing of their face.19 Chinese patients may interpret acne lesions as yin-yang imbalances.20 Our data demonstrated a positive correlation between acne burden and country wealth, which supports previous studies showing that acne prevalence is lower in rural, nonindustrialized areas than in modernized Western populations.18,21 This correlation is likely due to an interplay of many factors, such as differences in access to health care, socioeconomic status of patients, and cultural perceptions of skin care and beauty.18 Additionally, underdiagnosis may contribute to the lower prevalence of acne in nonindustrialized areas.

AA is an inflammatory dermatosis, with a high burden in Asia. AA is estimated to affect up to 2.13% of the global population, and the prevalence has been reported to differ significantly between Asia (1.46%), North America (2.47%), and Europe (0.58%).22 Our analysis showed a strong correlation between high-income countries and the burden of AA in Asia. One explanation for this disparity could be the misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of AA and its associated comorbidities in lower socioeconomic status patients because of the current paradigm that hair loss is purely a cosmetic illness.23 Furthermore, hair often represents an essential element of femininity, fertility, and female attractiveness in society and may possibly have more profound psychosocial implications among wealthier societies in Asia.23

Overall, skin cancer burden is relatively low in Asia. The incidence of cutaneous melanoma varies by ethnicity, with white populations having a substantially higher incidence rate (21.9 to 55.9 per 100,000) than Asian populations (0.2 to 0.5 per 100,000).24, 25, 26 The incidence of NMSC has also been reported to be higher in white patients.27,28 However, east and southeast Asia comprise approximately one-third of the world population; thus, the skin cancer burden is not entirely insignificant in terms of the absolute numbers in this region.29 Additionally, acral lentiginous melanoma is a common subtype of melanoma in Asian populations, comprising between 50% and 58% of cutaneous melanomas.30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Acral lentiginous melanomas typically present in areas with minimal or no sun exposure, such as palms, soles, and nails, and can be difficult to recognize and diagnose.33,35 Studies have shown that Asian melanoma patients typically present with more advanced disease and low 5-year survival rates, suggesting that skin cancer may be under-reported in Asian countries.31,36 Future skin cancer interventions in Asia should focus on a heightened awareness of acral melanomas in this population as well as early diagnosis and effective treatment strategies.

Our results also showed that Asian countries with lower GDP per capita had a higher burden of many infectious diseases, including leishmaniasis, viral skin infections, fungal infections, syphilis, tuberculosis, HIV, and scabies. Multiple factors may contribute to transmissibility of these diseases in resource-poor areas, such as lack of access to health care services, poor hygiene conditions, and overcrowding.37, 38, 39, 40 In particular, southeast Asia is reported to be a region with emerging infectious diseases because of rapid population growth, urbanization, increased population migration, and extensive livestock production.41,42 The burden of cutaneous leishmaniasis is increasing substantially in many Asian countries, with DALYs in Syria increasing an average of 9% annually from 1990 to 2017.8 From 2010 to 2013 alone, the incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Syria nearly doubled.43 This drastic change may be attributed to a massive human displacement in Syria, associated with increasing violence due to a civil war and terrorist activity in the Middle East. As a result, an ecologic disruption of sandflies (Phlebotomus papatasi), which transmits cutaneous leishmaniasis, has led to an emergence in areas where the displaced Syrians and disease reservoirs coexist.43

We showed scabies to be another burdensome infectious disease in Asia, consistent with previous studies.44 Eastern Asia, southeast Asia, and southern Asia are the top 5 regions in the world with the greatest age-standardized DALY burden caused by scabies.44 Scabies has a high prevalence in tropical developing countries as overcrowding permits the rapid spread of the disease, and resources for proper health care in these regions are scarce.44, 45, 46 Since 2017, scabies has been considered by the World Health Organization as a neglected tropical disease.47 Low-income countries face major constraints of health care resources and may not have the capacity to adequately respond to infectious diseases.48

The GBD database has several limitations, and the burden of skin disease is likely to be underestimated.49 The International Classification of Diseases system is used for the GBD database and may categorize skin conditions under other classifications. For example, melanoma is categorized under “cancer.” Additionally, there may be sparse data for certain geographic regions if they do not utilize the International Classification of Diseases system. Furthermore, there are possible confounding intrinsic and/or extrinsic differences between individuals of different countries. Stigma associated with dermatologic diseases may differ across higher socioeconomic status countries as individuals may rate DALYs differently. Future studies analyzing and confirming our findings at an individual level may be warranted prior to developing potential public health solutions.

Currently, there is a paucity of literature investigating the burden of emerging dermatologic conditions in different countries within Asia. There is a high burden of skin disease in Asia, which can cause a significant impact on the quality of life of the patients. To reduce this burden, interventions should be country-specific and directed toward diseases causing the highest burden. Future studies are needed to comprehensively and properly address the socioeconomic differences in the burden of skin disease.

Footnotes

Funding sources: The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) was partially funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. This research has been conducted as part of the GBD, coordinated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. The GBD was partially funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The work has not been previously presented.

Conflicts of interest: Dr Urban is a collaborator with the Global Burden of Disease. This article was not developed with consultation or support from the Global Burden of Disease research team. Drs Giesey, Mehrmal, Uppal, and Delost and Author Chu have no conflicts of interest to declare.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Karimkhani C., Dellavalle R.P., Coffeng L.E. Global skin disease morbidity and mortality: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):406–412. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Health statistics and information systems . 2014. Global Health Estimates.https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Bank World development indicators 2017. Accessed January 19, 2020. 2017. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26447 Available at:

- 5.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2018. Data from: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/findings-global-burden-disease-study-2017 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Frequently asked questions. Accessed May 23, 2020. http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/faq Available at:

- 7.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . 2018. Protocol for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study (GBD)http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/about/protocol Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Country profiles. Accessed June 9, 2020. http://www.healthdata.org/results/country-profiles Available at:

- 9.Hong S., Son D.K., Lim W.R. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis and the comorbidity of allergic diseases in children. Environ Health Toxicol. 2012;27:e2012006. doi: 10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider L., Hanifin J., Boguniewicz M. Study of the atopic march: development of atopic comorbidities. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):388–398. doi: 10.1111/pde.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai T.F., Rajagopalan M., Chu C.Y. Burden of atopic dermatitis in Asia. J Dermatol. 2019;46(10):825–834. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law M.P., Chuh A.A., Lee A., Molinari N. Acne prevalence and beyond: acne disability and its predictive factors among Chinese late adolescents in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(1):16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh D.H., Kim B.Y., Min S.U. A multicenter epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Korea. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50(6):673–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han X.D., Oon H.H., Goh C.L. Epidemiology of post-adolescence acne and adolescence acne in Singapore: a 10-year retrospective and comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(10):1790–1793. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder M.M., Sigurdsson V., van Zuuren E.J. Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris. Evaluation of the relation between a change in clinical acne severity and psychosocial state. Dermatology. 2001;203(2):124–130. doi: 10.1159/000051726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhate K., Williams H.C. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(3):474–485. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn L.K., O'Neill J.L., Feldman S.R. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynn D.D., Umari T., Dunnick C.A., Dellavalle R.P. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:13–25. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S55832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quarles F.N., Johnson B.A., Badreshia S. Acne vulgaris in richly pigmented patients. Dermatol Ther. 2007;20(3):122–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin H.E. Tricks for improving compliance with acne therapy. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(4):224–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf R., Matz H., Orion E. Acne and diet. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H.H., Gwillim E., Patel K.R. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marks D.H., Penzi L.R., Ibler E. The medical and psychosocial associations of alopecia: recognizing hair loss as more than a cosmetic concern. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(2):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garbe C., McLeod G.R., Buettner P.G. Time trends of cutaneous melanoma in Queensland, Australia and Central Europe. Cancer. 2000;89(6):1269–1278. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000915)89:6<1269::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka H., Tsukuma H., Tomita S. Time trends of incidence for cutaneous melanoma among the Japanese population: an analysis of Osaka Cancer Registry data, 1964-95. J Epidemiol. 1999;9(6SuppI):S129–S135. doi: 10.2188/jea.9.6sup_129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sng J., Koh D., Siong W.C., Choo T.B. Skin cancer trends among Asians living in Singapore from 1968 to 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61(3):426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naruse K., Ueda M., Nagano T. Prevalence of actinic keratosis in Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1997;15(3):183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(97)00602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford P.T. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21(4):170–177. 206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang J.W., Guo J., Hung C.Y. Sunrise in melanoma management: time to focus on melanoma burden in Asia. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13(6):423–427. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang J.W. Cutaneous melanoma: Taiwan experience and literature review. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33(6):602–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chi Z., Li S., Sheng X. Clinical presentation, histology, and prognoses of malignant melanoma in ethnic Chinese: a study of 522 consecutive cases. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luk N.M., Ho L.C., Choi C.L., Wong K.H., Yu K.H., Yeung W.K. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors of cutaneous melanoma among Hong Kong Chinese. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29(6):600–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H.Y., Chay W.Y., Tang M.B., Chio M.T., Tan S.H. Melanoma: differences between Asian and Caucasian patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2012;41(1):17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang J.W. Acral melanoma: a unique disease in Asia. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(11):1272–1273. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura Y., Fujisawa Y. Diagnosis and management of acral lentiginous melanoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19(8):42. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0560-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang J.W., Yeh K.Y., Wang C.H. Malignant melanoma in Taiwan: a prognostic study of 181 cases. Melanoma Res. 2004;14(6):537–541. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200412000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hicks M.I., Elston D.M. Scabies. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22(4):279–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hay R.J., Steer A.C., Engelman D., Walton S. Scabies in the developing world—its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibbs S. Skin disease and socioeconomic conditions in rural Africa: Tanzania. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35(9):633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb03687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niyonsenga T., Trepka M.J., Lieb S., Maddox L.M. Measuring socioeconomic inequality in the incidence of AIDS: rural-urban considerations. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):700–709. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0236-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones K.E., Patel N.G., Levy M.A. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coker R.J., Hunter B.M., Rudge J.W., Liverani M., Hanvoravongchai P. Emerging infectious diseases in southeast Asia: regional challenges to control. Lancet. 2011;377(9765):599–609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Salem W.S., Pigott D.M., Subramaniam K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis and conflict in Syria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(5):931–933. doi: 10.3201/eid2205.160042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karimkhani C., Colombara D.V., Drucker A.M. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(12):1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romani L., Steer A.C., Whitfeld M.J., Kaldor J.M. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(8):960–967. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romani L., Koroivueta J., Steer A.C. Scabies and impetigo prevalence and risk factors in Fiji: a national survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization Scabies and other ectoparasites. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/scabies-and-other-ectoparasites/en/#:∼:text=The%20Disease&text=In%202017%2C%20scabies%20and%20other,Technical%20Advisory%20Group%20for%20NTDs Available at:

- 48.Kanchanachitra C., Lindelow M., Johnston T. Human resources for health in southeast Asia: shortages, distributional challenges, and international trade in health services. Lancet. 2011;377(9767):769–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seth D., Cheldize K., Brown D., Freeman E.F. Global burden of skin disease: inequities and innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2017;6(3):204–210. doi: 10.1007/s13671-017-0192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]