Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a relatively rare disease that is often confused with pancreatic cancer or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The histological features of IMTs show that tissue from this type of tumor contains an intermingling of fibroblast and myofibroblast proliferation, accompanied by a varying degree of inflammatory cell infiltration.

CASE SUMMARY

The management of an IMT occurring at the neck of the pancreas is presented in this paper. A 66-year-old female patient was diagnosed with a pancreatic neck mass after a series of tests. The patient underwent enucleation of the pancreatic neck tumor after a pathological diagnosis of IMT. Previous research on the clinical features, pathological diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic IMTs was reviewed. Compared with previous reports, this is a unique case of enucleation of a pancreatic IMT.

CONCLUSION

The enucleation of pancreatic IMTs may be a safe and efficient surgical method for managing such tumors with a better prognosis. Further cases are required to explore surgical measures for pancreatic IMTs.

Keywords: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, Pancreatic neck, Enucleation, Case report

Core Tip: Pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a relatively rare disease that is often confused with pancreatic cancer or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. We present herein a 66-year-old female patient who was diagnosed with a pancreatic neck mass after a series of tests. The patient underwent enucleation of a pancreatic neck tumor after pathological diagnosis of IMT. Compared with previous reports, this is a unique case of enucleation of a pancreatic IMT. We conclude that the enucleation of pancreatic IMTs may be a safe and efficient surgical method for managing such tumors with a better prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) is a rare mesenchymal tumor of unknown pathogenesis and aggressive malignant potential with a global incidence of less than 1%[1,2]. IMTs most commonly occur in the lungs of children and young adults, followed by the head and neck[3], liver[4], pancreas[5], genitourinary tract[6] and thyroid[7]. The clinical presentation of pancreatic IMTs varies depending on their anatomic location, and the final diagnosis of most lesions requires a pathological examination. The pancreatic head is the most common site for pancreatic IMTs and may be the first choice for surgical resection. Of 29 cases of pancreatic IMT reported in the English literature, none have been treated by enucleation of the tumor. Herein, an unusual pancreatic neck IMT occurring in a 66-year-old female patient is presented, and this may be the first case of enucleation of a pancreatic IMT. Pancreatic IMTs have a relatively low incidence and unspecific manifestations. The clinical and histological features of pancreatic IMTs, as well as their diagnosis and treatment, are discussed in this paper.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 66-year-old female patient was admitted to Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital on January 13, 2020 for a pancreatic mass.

History of present illness

Abdominal ultrasonography of the patient showed hyperechoic foci in the neck of the pancreas after a follow-up examination in the local hospital 4 d prior, and then the patient was transferred to our department for further treatment.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of right pulmonary wedge resection for adenocarcinoma in 2014 and right hemicolectomy for colon cancer in 2018.

Physical examination

The physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory examinations, including complete blood count, C-reactive protein and tumor markers, were all within the normal range.

Imaging examinations

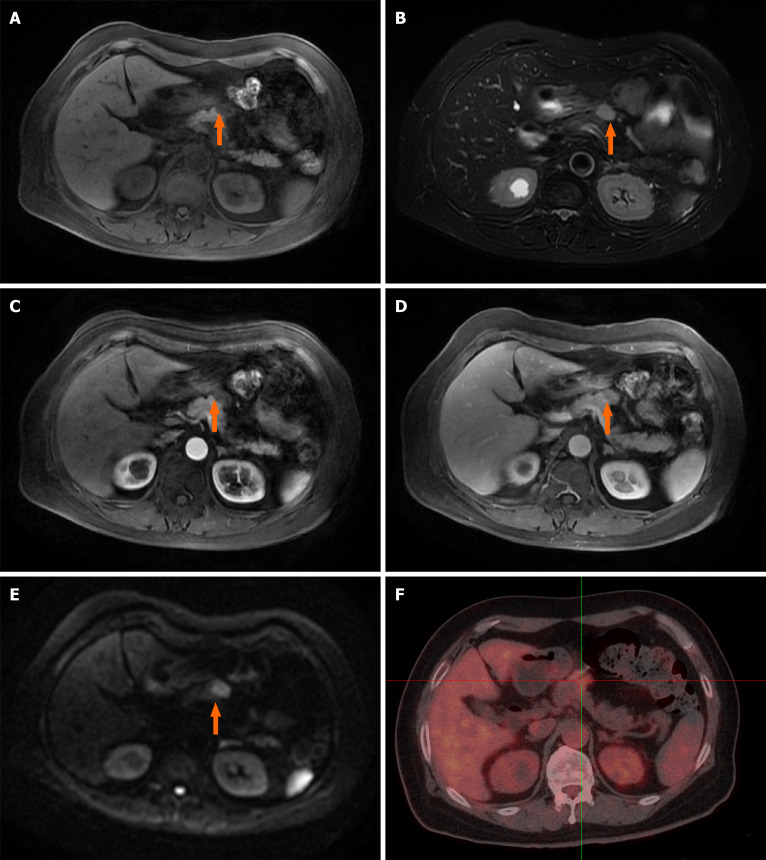

However, the ultrasound scan revealed a 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm mass in the neck of the pancreas. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging scan showed an abnormal soft tissue heterogeneous mass in the neck of the pancreas, which appeared hyperintense on the T1-weighted image and mildly hyperintense on the T2-weighted image. A centripetal enhancement pattern was observed during the delayed phase of contrast imaging (Figure 1A-E). Whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) examination revealed a 2.3 cm × 1.4 cm, mild-to-moderate FDG uptake nodule in front of the pancreatic neck (SUVmax 3.87) with normal scans of the head, neck, chest and colon (Figure 1F). The imaging findings were highly suggestive of pancreatic IMT. However, the possibility of a metastatic tumor could not be ruled out due to the history of lung and colon cancer.

Figure 1.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography reveal one irregular lesion in the pancreatic neck. A: The lesion of the pancreatic neck (orange arrow) was hyperintense on T1-weighted imaging; B: The irregular lesion (orange arrow) was slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging; C: Arterial phase imaging revealed slight enhancement of the pancreatic lesion (orange arrow); D: The lesion (orange arrow) showed persistent enhancement in venous phase imaging; E: The pancreatic mass (orange arrow) had significant hyperintensity in diffusion-weighted imaging; F: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography revealed a hypermetabolic pancreatic neck nodule measuring 2.3 cm × 1.4 cm (SUVmax = 3.87).

Histopathological examination

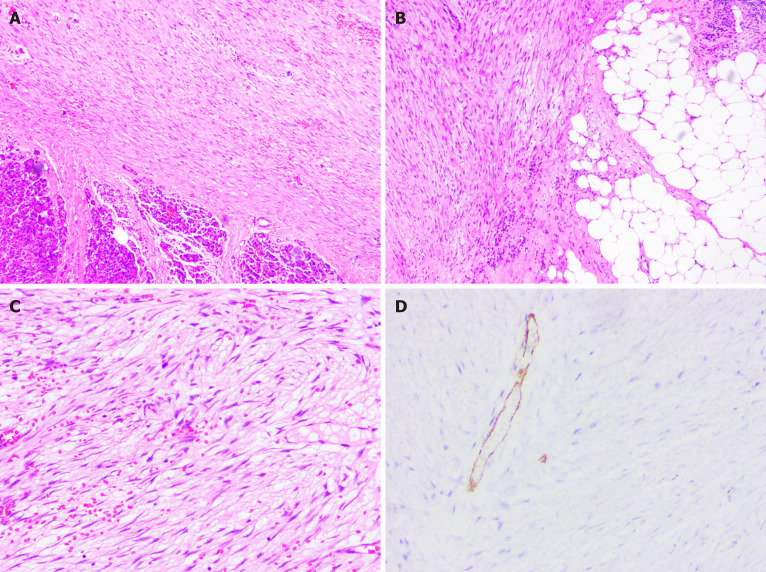

A detailed postoperative histopathological examination revealed that the carcinoma cells stained positively for desmin, vimentin, CD34, CD31, BCL2 and β-catenin and negatively for S-100, Pan-CK (AE1/AE3), caldesmon, DOG1, CD117, smooth muscle actin and P53.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of pancreatic neck IMT was determined on the basis of the histopathological results (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The pathological findings of the resected specimen revealed inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. A-C: Histological images showed mixed components of dense myofibroblastic tissues and few inflammatory cells, with neoplastic cells infiltrating the surrounding fat tissue (hematoxylin and eosin staining); D: Immunohistochemical studies showed positivity for smooth muscle actin.

TREATMENT

The patient with pancreatic IMT underwent enucleation of the pancreatic mass after multidisciplinary team discussion. During the laparotomy, a hard protruding mass with a size of 2.3 cm × 1.5 cm was observed on the pancreatic neck and subsequently enucleated. The entire mass was fleshy with a grayish-white cut surface and was confirmed with the intraoperative frozen section to be an IMT.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

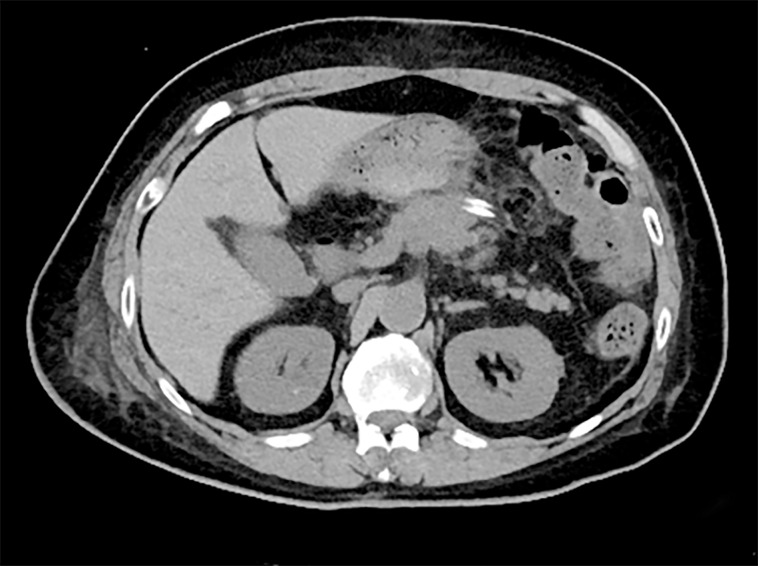

The postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 11 (Figure 3). No adjuvant treatment was administered, and no obvious signs of metastasis or recurrence in the next 10 mo of follow-up were observed.

Figure 3.

Ten days after surgical resection, computed tomography showed that the pancreatic neck inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor was enucleated, and the tissue of the pancreas remained intact.

DISCUSSION

IMT, first reported in the lungs[8,9], is a special type of disease that is often termed differently in primary research, including designations such as plasma cell granuloma, plasma cell pseudotumor, inflammatory pseudotumor, inflammatory fibroxanthoma and histiocytoma[10]. IMTs can occur almost anywhere in the body, including the lungs, liver, bladder, mesentery and neck[11-13]. However, an IMT arising from the pancreas is extremely rare. A complete search of the literature from 1900 to 2020 using the PubMed database with the search terms “inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor,” “IMT,” “pancreas” and “pancreatic” was performed, and only 29 reported cases were discovered. A brief literature review of reported cases with pancreatic IMT was conducted to better understand pancreatic IMT, as summarized in Table 1[5,10,14-34]. Of these patients, 20 were male (20/29, 69%), and 9 were female (9/29, 31%), with an obvious male predilection. The tumor diameter for all reported cases ranged from 1.5 to 15.0 cm. Most tumors occurred in the pancreatic head (21/29 patients), followed by the pancreatic tail (4/29 patients) and pancreatic body (3/29 patients), suggesting that pancreatic IMT was more common in the pancreatic head.

Table 1.

Reported cases of pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the English literature

|

Cases

|

Sex

|

Age in yr

|

Location

|

Diameter in cm

|

Symptoms

|

Treatment

|

Follow-up

|

Ref.

|

| 1 | M | 70 | PT | 3.8 | Asymptomatic | DP + splenectomy | Disease-free at 10 mo | Pungpapong et al[29], 2004 |

| 2 | M | 62 | PH | 3 | Jaundice | PD | Disease-free at 6 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 3 | M | 56 | PH | no | Jaundice | PD | Disease-free at 5 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 4 | M | 50 | PH | 5 | Jaundice, abdominal pain | PD | Disease-free at 4 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 5 | F | 57 | PH | Not available | Jaundice | PD | Disease-free at 3 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 6 | M | 45 | PH | Not available | Jaundice | PD | Disease-free at 10 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 7 | F | 32 | PH | 3 | Abdominal pain | PD | Disease-free at 12 yr | Wreesmann et al[14], 2001 |

| 8 | F | 42 | PB | 7 | Abdominal pain, weight loss | DP | Disease-free at 6 mo | Kroft et al[15], 1998 |

| 9 | F | 8 | PBT | 10.7 | Abdominal mass | DP | Disease-free at 2 yr | Shankar et al[16], 1998 |

| 10 | M | 35 | PH | 5 × 4 × 3 | Abdominal pain, weight loss | PD | Lung metastasis at 6 yr | Walsh et al[17], 1998 |

| 11 | M | 55 | PH | 1.5 | Asymptomatic | PD | Disease-free at 28 mo | Yamamoto et al[10], 2002 |

| 12 | M | 69 | PBT | Not available | Abdominal pain | DP + splenectomy + colon splenic flexure | Died after 7 mo of hospitalization due to sepsis | Esposito et al[18], 2004 |

| 13 | M | 65 | PB | 2 | Asymptomatic | DP + splenectomy | Disease-free at 3 yr | Dulundu et al[19], 2007 |

| 14 | M | 56 | PT | 5 × 7 | Melena | DP + splenectomy | Disease-free at 18 mo | Sim et al[30], 2008 |

| 15 | F | 13 | PH | 3 | Vomiting, weight loss | PD | Disease-free at 7 yr | Dagash et al[20], 2009 |

| 16 | M | 10 | PH | 2.2 | Abdominal pain, anepithymia | Prednisolone, cefuroxime | Disease-free at 6 yr | Dagash et al[20], 2009 |

| 17 | M | 19 | PT | 8.2 × 6.5 × 6.0 | Abdominal pain | DP + splenectomy | Disease-free at 6 yr | Hassan et al[22], 2010 |

| 18 | M | 44 | PH | 6 × 4 | Abdominal pain, vomiting | PD | Disease-free at 1 yr | Schütte et al[23], 2010 |

| 19 | M | 65 | PH | Not available | Abdominal pain | PD | Not available | Lacoste et al[25], 2012 |

| 20 | M | 0.5 | PH | 4 | Jaundice | PD | Disease-free at 3.5 yr | Tomazic et al[31], 2015 |

| 21 | F | 32 | PH | 4.8 × 3.2 | Abdominal pain | PD | Disease-free at 2.5 yr | Panda et al[26], 2015 |

| 22 | M | 46 | PH | 8 × 6 × 5 | Jaundice | PD | Not available | Battal et al[27], 2016 |

| 23 | M | 69 | PH | 4 × 3 | Vomiting, anepithymia | PD | Disease-free at 3 yr | Ding et al[21], 2016 |

| 24 | M | 15 | PH | 5 × 5 × 4.3 | Abdominal pain, fever | PD | Not available | Liu et al[24], 2017 |

| 25 | M | 1 | PH | 4 × 3 | Asymptomatic | PD | Not available | Berhe et al[34], 2019 |

| 26 | F | 82 | PH | 5 | Abdominal pain | None | Disease-free at 9 mouths | Matsubayashi et al[28], 2019 |

| 27 | M | 61 | PT | 15 × 13 × 7 | Abdominal pain | DP + left surrenalectomy + left hemicolectomy + splenectomy | Disease-free at 8 mo | İflazoğlu et al[5], 2020 |

| 28 | F | 11 | PH | 3.4 | Abdominal pain, weight loss | PD | Not available | Mcclain et al[32], 2000 |

| 29 | F | 13 | PH | 2.5 | Abdominal pain | PD | Disease-free at 4 yr | Zanchi et al[33], 2015 |

| 30 | F | 66 | PN | 2.3 × 1.5 | Asymptomatic | Enucleation | Disease-free at 9 mo | Current |

DP: Distal pancreatectomy; F: Female; M: Male; PB: Pancreatic body; PBT: Pancreatic body and tail; PD: Pancreaticoduodenectomy; PH: Pancreatic head; PN: Pancreatic neck; PT: Pancreatic tail.

Clinical manifestations

Pancreatic IMT can occur at all ages but shows a preference for children and young adults[35]. All reported cases range from 6 mo to 82 years (mean age: 42 years). As described previously, the clinical presentation of pancreatic IMT varies depending on its anatomic location and can range from asymptomatic to hemorrhagic shock due to rupture of the spleen[19,22]. Nonetheless, almost all pancreatic IMTs have similar nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, abdominal distension, abdominal pain, general fatigue and weight loss. Obstructive jaundice may be noted in typical patients with a pancreatic head IMT. The tumor can also obstruct the pancreatic duct and induce chronic pancreatitis with abdominal discomfort, diarrhea and indigestion[23]. An IMT arising from the pancreatic tail can also obstruct blood vessels of the spleen, resulting in rupture of the spleen with severe abdominal pain and hemorrhagic shock[22]. However, the IMT of our patient arose from the neck of the pancreas, and she had no special symptoms.

Clinical evaluation

The preoperative laboratory findings were nonspecific for the diagnosis of pancreatic IMT. Only a few patients with a solitary mass occurring in the head of the pancreas may have elevated total serum bilirubin, amylase and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 due to obstruction of the bile duct or pancreatic duct[26]. Moreover, the radiological features are often deceptive. Ultrasound, CT and magnetic resonance imaging examinations showed mass lesions mimicking pancreatic cancer or pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Similar to that of other malignant tumors, whole-body 18F-FDG positron emission tomography/CT also showed an elevated SUVmax[36], which can distinguish IMTs from non-neoplastic lesions, such as pancreatic pseudocysts and swollen lymph nodes. In addition, whole-body 18F-FDG positron emission tomography /CT is the best tool to detect tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. Even standard intraoperative frozen pathology may not provide definitive information to distinguish pancreatic IMTs from pancreatic inflammatory pseudotumors.

Pathology/pathophysiology

The definitive diagnosis of IMTs relies on histological evaluations and immunohistochemical tests[37]. The histological features of IMTs are spindle-shaped cells accompanied by varying degrees of inflammatory cells[38,39]. Coffin et al[37] suggested that clonal cytogenetic abnormalities involving the anaplastic lymphoma kinase gene on the short arm of chromosome 2 at 2p23 occur in approximately 50% of IMTs[37]. This can be a useful test for a definitive clinicopathologic diagnosis. In addition, most extrapulmonary IMTs display immunohistochemical reactivity for spinal muscular atrophy, desmin, the tissue cell marker CD68 and the vascular marker CD34[40].

Treatment

To date, no standard consensus regarding the treatment of pancreatic IMT has been reached. However, surgical resection of the lesion is recommended as the primary therapeutic option for pancreatic IMT. The surgical approach is related to the location of the lesion on the pancreas. For pancreatic head IMTs, pancreaticoduodenectomy is recommended, while distal pancreatectomy is recommended for pancreatic body or tail IMTs. Pancreatic IMTs often invade surrounding organs such as the colon, duodenum and stomach. However, these theories are not widely accepted for such low-grade malignant lesions. Whether radical surgery is necessary requires a large number of further clinical studies.

Radiation therapy, chemotherapy and high-dose steroid therapy have also been used in patients with incomplete resection, impossible resection or malignant disease status postsurgical resection[20,28,41]. Spontaneous regression of pancreatic IMTs has been reported infrequently[28]. Given that our patient was an elderly and infirm female with pancreatic neck IMT only, multidisciplinary team discussion suggested that enucleation would be a more beneficial therapeutic option. No adjuvant treatment was administered following the enucleation of the pancreatic IMT. The patient remained symptom-free and healthy without tumor recurrence or metastasis 10 mo after surgery. Although only one patient with IMT has been reported to have undergone enucleation, such operative procedures could be considered in the future. More cases are required to explore the surgical treatment of pancreatic IMTs.

Prognosis

Pancreatic IMT is regarded as a low-grade malignancy with a generally favorable prognosis. However, a close and long-term follow-up after surgery must be carried out due to its potential for malignancy, distant metastasis and recurrence.

CONCLUSION

This paper reports a rare case of IMT of the pancreatic neck managed with enucleation treatment to confirm whether radical surgery could be avoided. This is the first reported case in which enucleation usage resulted in a favorable prognosis of pancreatic IMT. Surgical resection may be the preferred treatment and may provide a better prognosis. However, using enucleation as a surgical measure for treating patients with IMT may also yield a good prognosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the support of the Department of Radiology at Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Shuren University Shulan International Medical College.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 18, 2021

First decision: March 11, 2021

Article in press: June 1, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cianci P, Tomažič A S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Zhi-Tao Chen, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Shuren University Shulan International Medical College, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China; School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yao-Xiang Lin, School of Medicine, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Meng-Xia Li, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China; Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Ting Zhang, Department of Pathology, Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Shuren University Shulan International Medical College, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Da-Long Wan, Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Sheng-Zhang Lin, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Shulan (Hangzhou) Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang Shuren University Shulan International Medical College, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China. wzf2lsz@163.com.

References

- 1.Panagiotopoulos N, Patrini D, Gvinianidze L, Woo WL, Borg E, Lawrence D. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the lung: a reactive lesion or a true neoplasm? J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:908–911. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD. The 2015 WHO classification of lung tumors. Pathologe. 2014;35 Suppl 2:188. doi: 10.1007/s00292-014-1974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao F, Zhong R, Li GH, Zhang WD. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the head and neck. Acta Radiol. 2014;55:434–440. doi: 10.1177/0284185113500165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thavamani A, Mandelia C, Anderson PM, Radhakrishnan K. Pediatric Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Liver: A Rare Cause of Portal Hypertension. ACG Case Rep J. 2019;6:1–4. doi: 10.14309/crj.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.İflazoğlu N, Kaplan Kozan S, Biri T, Ünlü S, Gökçe H, Doğan S, Gökçe ON. Pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor presenting with extracolonic obstruction. Turk J Surg. 2020;36:233–237. doi: 10.5578/turkjsurg.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palanisamy S, Chittawadagi B, Dey S, Sabnis SC, Nalankilli VP, Subbiah R, Chinnusamy P. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of Colon Mimicking Advanced Malignancy: Report of Two Cases with Review of Literature. Indian J Surg. 2020;82:1280–1283. [Google Scholar]

- 7.An N, Luo Y, Wang J, Wang XL, Man GD, Song YD. [Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of thyroid: a case report] Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;53:148–149. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-0860.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin CM, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao HD, Wu T, Wang JQ, Zhang WD, He XL, Bao GQ, Li Y, Gong L, Wang Q. Primary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the breast with rapid recurrence and metastasis: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:97–100. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto H, Watanabe K, Nagata M, Tasaki K, Honda I, Watanabe S, Soda H, Takenouti T. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:116–119. doi: 10.1007/s005340200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alabbas Z, Issa M, Omran A, Issa R. Mesenteric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor as a rare cause of small intestinal intussusception. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa322. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao J, Han D, Gao M, Liu M, Feng C, Chen G, Gu Y, Jiang Y. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the neck with thyroid invasion: a case report and literature review. Gland Surg. 2020;9:1042–1047. doi: 10.21037/gs-20-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inamdar AA, Pulinthanathu R. Malignant transformation of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of urinary bladder: A rare case scenario. Bladder (San Franc) 2019;6:e39. doi: 10.14440/bladder.2019.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wreesmann V, van Eijck CH, Naus DC, van Velthuysen ML, Jeekel J, Mooi WJ. Inflammatory pseudotumour (inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour) of the pancreas: a report of six cases associated with obliterative phlebitis. Histopathology. 2001;38:105–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroft SH, Stryker SJ, Winter JN, Ergun G, Rao MS. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:277–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02784953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shankar KR, Losty PD, Khine MM, Lamont GL, McDowell HP. Pancreatic inflammatory tumour: a rare entity in childhood. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:422–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh SV, Evangelista F, Khettry U. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreaticobiliary region: morphologic and immunocytochemical study of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:412–418. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esposito I, Bergmann F, Penzel R, di Mola FF, Shrikhande S, Büchler MW, Friess H, Otto HF. Oligoclonal T-cell populations in an inflammatory pseudotumor of the pancreas possibly related to autoimmune pancreatitis: an immunohistochemical and molecular analysis. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:119–126. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0949-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dulundu E, Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas--a case report. Biosci Trends. 2007;1:167–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dagash H, Koh C, Cohen M, Sprigg A, Walker J. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreas: a case report of 2 pediatric cases--steroids or surgery? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1839–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding D, Bu X, Tian F. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in the head of the pancreas with anorexia and vomiting in a 69-year-old man: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:1546–1550. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassan KS, Cohen HI, Hassan FK, Hassan SK. Unusual case of pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor associated with spontaneous splenic rupture. World J Emerg Surg. 2010;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schütte K, Kandulski A, Kuester D, Meyer F, Wieners G, Schulz HU, Malfertheiner P. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Pancreatic Head: An Unusual Cause of Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis - Case Presentation of a Palliative Approach after Failed Resection and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4:443–451. doi: 10.1159/000320953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu HK, Lin YC, Yeh ML, Chen YS, Su YT, Tsai CC. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the pancreas in children: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5870. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacoste L, Galant C, Gigot JF, Lacoste B, Annet L. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreatic head. JBR-BTR. 2012;95:267–269. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panda D, Mukhopadhyay D, Datta C, Chattopadhyay BK, Chatterjee U, Shinde R. Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor Arising in the Pancreatic Head: a Rare Case Report. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:538–540. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1322-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Battal M, Kartal K, Tuncel D, Bostanci O. Inflammatory myofibroblastic pancreas tumor: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4:1122–1124. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsubayashi H, Uesaka K, Sasaki K, Shimada S, Takada K, Ishiwatari H, Ono H. A Pancreatic Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor with Spontaneous Remission: A Case Report with a Literature Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9040150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pungpapong S, Geiger XJ, Raimondo M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor presenting as a pancreatic mass: a case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2004;5:360–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sim A, Lee MW, Nguyen GK. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the pancreas. Can J Surg. 2008;51:E23–E24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomazic A, Gvardijancic D, Maucec J, Homan M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the pancreatic head - a case report of a 6 mo old child and review of the literature. Radiol Oncol. 2015;49:265–270. doi: 10.2478/raon-2014-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mcclain MB, Burton EM, Day DS. Pancreatic pseudotumor in an 11-year-old child: imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol . 2000;30:610–613. doi: 10.1007/s002470000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanchi C, Giurici N, Martelossi S, Cheli M, Sonzogni A, Alberti D. Myofibroblastic Tumor of the Pancreatic Head: Recurrent Cholangitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61:e28–e29. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berhe S, Goldstein S, Thompson E, Hackam D, Rhee DS, Nasr IW. Challenges in Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors in Children. Pancreas. 2019;48:e27–e29. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonaka D, Birbe R, Rosai J. So-called inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour: a proliferative lesion of fibroblastic reticulum cells? Histopathology. 2005;46:604–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manning MA, Paal EE, Srivastava A, Mortele KJ. Nonepithelial Neoplasms of the Pancreas, Part 2: Malignant Tumors and Tumors of Uncertain Malignant Potential From the Radiologic Pathology Archives. Radiographics. 2018;38:1047–1072. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: comparison of clinicopathologic, histologic, and immunohistochemical features including ALK expression in atypical and aggressive cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:509–520. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213393.57322.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coindre JM. [New WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone] Ann Pathol. 2012;32:S115–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, Dehner LP. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ong HS, Ji T, Zhang CP, Li J, Wang LZ, Li RR, Sun J, Ma CY. Head and neck inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT): evaluation of clinicopathologic and prognostic features. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Som PM, Brandwein MS, Maldjian C, Reino AJ, Lawson W. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the maxillary sinus: CT and MR findings in six cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:689–692. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.3.8079869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]