Abstract

Objective

To quantify general practitioners’ (GPs’) turnover in England between 2007 and 2019, describe trends over time, regional differences and associations with social deprivation or other practice characteristics.

Design

A retrospective study of annual cross-sectional data.

Setting

All general practices in England (8085 in 2007, 6598 in 2019).

Methods

We calculated turnover rates, defined as the proportion of GPs leaving a practice. Rates and their median, 25th and 75th percentiles were calculated by year and region. The proportion of practices with persistent high turnover (>10%) over consecutive years were also calculated. A negative binomial regression model assessed the association between turnover and social deprivation or other practice characteristics.

Results

Turnover rates increased over time. The 75th percentile in 2009 was 11%, but increased to 14% in 2019. The highest turnover rate was observed in 2013–2014, corresponding to the 75th percentile of 18.2%. Over time, regions experienced increases in turnover rates, although it varied across English regions. The proportion of practices with high (10% to 40%) turnover within a year almost doubled from 14% in 2009 to 27% in 2019. A rise in the number of practices with persistent high turnover (>10%) for at least three consecutive years was also observed, from 2.7% (2.3%–3.1%) in 2007 to 6.3% (5.7%–6.9%) in 2017. The statistical analyses revealed that practice-area deprivation was moderately associated with turnover rate, with practices in the most deprived area having higher turnover rates compared with practices in the least deprived areas (incidence rate ratios 1.09; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.13).

Conclusions

GP turnover has increased in the last decade nationally, with regional variability. Greater attention to GP turnover is needed, in the most deprived areas in particular, where GPs often need to deal with more complex health needs. There is a large cost associated with GP turnover and practices with very high persistent turnover need to be further researched, and the causes behind this identified, to allow support strategies and policies to be developed.

Keywords: primary care, health policy, organisation of health services, health economics, human resource management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study goes a step further than previous research, in quantifying and describing general practitioners’ (GPs’) actual turnover over a 12-year period, rather than ‘intention to leave’.

It used two national administrative datasets, regularly updated and monitored, which have the advantage of including everyone rather than only respondents to a survey.

It also presented methodological advances in combining multiple data sources containing information about the primary care workforce and historical data of individual GPs’ characteristics.

However, only a limited set of covariates was available in the national administrative datasets, when many more are relevant to turnover.

Finally, it was not possible to distinguish between those GPs who moved to a different practice, retired or left primary care completely.

Introduction

Primary care has a key role in the UK healthcare system, with general practitioners (GPs, family physicians in the USA) the first point of contact for patient care. However, recent data have shown that the GP workforce in England is going through a major crisis,1 reflected in increasing rates of early retirement and intentions to reduce hours of working or leave their practice in the near future.2 Despite this being a common problem for other European countries3 and globally,4 it seems to be particularly serious for the UK.3 5 According to an international survey of GPs from 2015, approximately 30% of GPs want to leave their profession within 5 years.3

A 2019 report conducted by the Health Foundation highlighted that while there has been an increase in the number of hospital-based doctors, the number of GPs has reduced6; National Health Service (NHS) staff retention has worsened since 2011/2012 and, despite this being a UK government priority, there has been no improvement in retention in recent years.6 Prior to the 2015 elections, the UK government promised 5000 more doctors in primary care by 2020.7 However, recent data from regional and national surveys indicate the number of full-time equivalent GPs per 1000 patients continues to decline. Regionally, GP surveys from West Midlands8 and South West England9 found that 41.9% and 70% of participants intended to leave the practice or were likely or very likely to pursue a career choice that would negatively impact the GP workforce within the next 5 years, respectively. Likewise, the most recent national survey of 2195 GPs in England conducted in 2017 reported that 39% intended to leave ‘direct patient care’ within 5 years, compared with 19.4% in 2005.2

GP retention measures the percentage of staff staying in a practice for a defined period of time. GP turnover measures the proportion of staff who leave. Both are important indicators of the behaviour of doctors in the primary care workforce.6 While retention is an indicator of the stability of a practice workforce, GP turnover is highly correlated with the desire to quit the profession, although this may in part be due to GPs retiring or simply moving practice.

Low retention or decreasing retention levels over time and high turnover rates are major issues for NHS primary care. High GP turnover is a concern for several reasons: it may be associated with practices experiencing recurring problems with recruitment and retention10; it may affect the ability to deliver primary care services4 and undermine continuity of care which in turn may affect the quality of patient care. For instance, healthcare received from multiple GPs can lead to conflicting therapeutic treatments and fragmented care.11 Conversely, the benefits of continuity of care have been documented in studies which linked greater continuity of care with higher patient satisfaction,12 reduction in costs of care,13 reduced risk of hospitalisation and lower mortality.14 Differential turnover across practices and regions could also lead to a maldistribution of GPs, exacerbating retention problems10 and health inequalities. It is also important to highlight that there is a large cost associated with GP turnover,15 estimated to be two to three times the doctor’s annual salary.16 These costs include direct costs (separation costs, recruitment, induction and temporary replacement costs),17 but also indirect or long-term costs such as overwork by other staff plus the ‘costs’ in terms of quality of care. For instance, lower quality of care may lead to fewer patients seeking early diagnosis/treatments with long-term costs for the NHS as a whole. Finally, GP turnover costs are likely to increase in the future due to the GP shortages which are linked but not necessarily are a consequence of turnover.

Despite existing concerns about retention and turnover levels in England, studies quantifying movements of the GP workforce are scarce with the most recent reporting data from the early 90s.10 Recently, Buchan et al in their report conclude that further research is required particularly to investigate actual turnover as opposed to intentions to leave.6 18

In England, detailed administrative data about the primary care workforce are collected and include practice-related characteristics as well as historical data on when a GP joins and leaves a practice. Compared with surveys, administrative data have the advantage that everyone is included rather than only the respondents and it is based on actual behaviour rather than intentions. However, these data have rarely been used to quantify actual GP turnover rates.

In this study, we used national data from NHS Digital, NHS Prescribing and the NHS Organisation Data Service (ODS) to explore GP turnover rates over time and regionally, as well as to identify practice-level factors associated with them.

Methods

The overall aim of the study was to explore turnover rates of GPs and look at trends in turnover in different regions over time in England between 2007 and 2019. In particular, the study aimed to: quantify rates of GP turnover in England, their trends over time, their differences across regions and the predictors of GP turnover.

Definition of GP turnover rates

With the aim of quantifying trends of GPs leaving general practices, turnover was defined as the number of GPs who leave a practice divided by the average of the number of GPs at the start and the number of GPs at the end of the year. This rate definition is similar to that used in previous studies on GPs turnover10 17 and the current definition used by the NHS.19

Where

Average number of GPs in a year=(GPs in a practice at the start of the year+GPs in a practice at the end of the year)/2;

GPs in a practice at the end of the year=Number of GPs at start of the year+Number of joiners–Number of leavers.

Furthermore, with the aim of having a comprehensive picture on the movement of GPs, two additional measures were calculated: joiners’ and retention rates, which describe (i) the proportion of GPs who join a practice during the year and (ii) the proportion of GPs who stay in a practice for the entire year, respectively. Therefore, while retention indicates the ability of a practice to retain its staff, a high rate of joiners is likely to generate a high rate of turnover due to the association of low tenure with likelihood to quit. Rates and statistical analyses of turnover are presented in the main paper, whereas retention and joiners’ rates are described and reported in online supplemental tables 1 and 2.

bmjopen-2021-049827supp001.pdf (536.3KB, pdf)

Data sources

GP workforce dataset

General practices are required to provide data about staff working at NHS practices or other primary care organisations in England. NHS Digital, previously the Health and Social Care Information Centre, regularly publishes workforce datasets which include information on individual GPs and practice-level characteristics since 1995. These datasets are publicly available on the NHS Digital website.20 This study used the annual datasets (September releases) between 2007 and 2020 and the files containing practice-level data containing all the information relative to a practice.

Membership of practices

GPs in England are issued a code when they start prescribing, the GPs Primary General National Code (GNC), which is associated with their main prescribing cost centre and is issued by the NHS Prescription Services (NHS RxS). These codes are published by the NHS ODS on behalf of the NHS RxS. In particular, information about individual prescribing code of GPs (GNC) and the date a GP has joined and left a practice, are included in the General Medical Practitioners data and the General Medical Practices, GPs-by-general practice data (GP membership-epracmem), respectively. In these data, each GP has an entry for every main prescribing cost centre (GP practice) where they have worked. Dates of when a GP joins and leaves a GP practice enables the calculation of GP turnover across a specified time window. These datasets include information only on those GPs who can prescribe, that is, GP partners and salaried GPs. These data are published free of charge and capture information on GP membership to each practice from 1974 and are updated weekly on the NHS Technology Reference data Update Distribution21 website. Data on GP membership of practices were extracted on the second week of November 2020. Online supplemental figure 1 summarises the data process.

Study design and study population

Practice-level GP workforce data were linked to the GPs-by-GPs practice data (GP membership-epracmem) using the practice code and each year included practices that were common in both data sources. The practice-level GP workforce files were used to identify practice characteristics and the GPs-by-GPs practice data (GP membership-epracmem) to calculate turnover rates combined for GP partners and salaried GPs given that these are the only GPs able to prescribe and whose information is included in the datasets. Joiners’ and retention rates are described and reported in online supplemental tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Statistical analyses

Only practices with at least 750 registered patients were included in the analyses. Smaller practices were omitted (714, 8.1%, practices during the entire study window) as they could have been reducing patient numbers in preparation for closure which itself would affect GP turnover; or they could be newly formed practices which might have exhibited different recruiting behaviours. Finally, practices with no GPs left at the end of the year in question (because they were closing in the following years) were excluded from the analyses (2006, 22.8% practices during the entire time window). A table with the distribution of these practices and their turnover rates are provided in online supplemental table 3.

GP turnover rate over time and by NHS regions

Using the GPs-by-GPs practice data (GP membership-epracmem), turnover rates were calculated for each practice and for every year in the study window (2007–2019). To summarise GP movement, the following analyses were performed. First, summary statistics including mean (SD), 25th, 50th, 75th percentiles were calculated and violin plots produced. Violin plots are similar to box plots (including the median as a marker and a box indicating the IQR), but overlaid with the distribution of the data for better visualisation. Second, the proportion of practices with low, medium, high and very high turnover rate (equal to 0%, between 0% and <10%, between 10% and <40% and ≥40%, respectively) were computed for every year. Although arbitrary, these thresholds were chosen to understand better the extent of turnover and whether there was a high proportion of practices with extreme values. Third, the proportion of practices with persistent high turnover (>10%) across 2, 3, 4 and 5 years window was calculated with the intent to explore whether practice turnover might have indicated a temporary situation (2 or 3 years persistent high turnover) or a continuing problem (4 or 5 years persistent high turnover). Finally, turnover rates were produced at regional level using the most recent classification of NHS region and rates compared between 2007 and 2019.

Predictors of GP turnover rates

To identify factors influencing turnover, count data models were fitted to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% CIs of turnover rates. Specifically, a negative binomial distribution model was employed, this is the most appropriate model in the presence of overdispersion of the data. To explore the hypothesis that social deprivation of people living in the area where a practice was located is likely to increase turnover, the variables included in the primary model were average levels of deprivation where the practice was located (Index of Multiple Deprivation, IMD, 2015) categorised in quintiles and year in the study window. There was a small proportion of missing data for IMD (0.08%) in the main analysis and type of contract (0.30%) in the sensitivity analyses. For these variables, an extra category was included to indicate a missing value.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of the results. (i) Restricting the analysis to practices active for the entire time-window to check whether opening or closing practices affected turnover rates. (ii) Excluding from the analysis practices that had an Alternative Provider Medical Service (APMS) contract rather than those having a General Medical Service or Personal Medical Service contract. This allowed us to explore whether turnover rates were affected by the type of contract of a practice. (iii) Fitting a random effect model with NHS region as random effect to understand whether regional variability influenced turnover rates. (iv) Restricting the analysis to 2015–2019 given that more information was available for this time-window and it was possible to include additional variables in the model other than practice-area social deprivation (IMD 2015) and year. These variables were full-time-equivalent (FTE) per 1000 patients ratio and proportion of salaried GPs in the practice, which were included to explore whether GPs workload and practice network structure (with salaried GPs more likely to leave) were associated with levels of turnover.

Patients and public involvement

Patients and public involvement (PPI) members were involved in the project. They did not contribute to the research question or study design, but provided feedback on the study findings. In particular, a forum group was organised with five PPI members. They agreed that GPs leaving a practice had a negative influence on patients’ quality and continuity of care. They highlighted the following points regarding the potential disruption of their relationship with their GP: lack of communication and feeling apprehensive when they had to meet a new or different GP. Overall a personal relationship with the GP was very important, although often practices did not meet patients’ expectations.

Results

GP turnover rates and their trends over time and by NHS region

After merging the GP workforce data with the GPs-by-GPs practice data (GP membership-epracmem), the number of practices included in the analyses decreased during the study window, from 8085 practices in 2007 to 6598 in 2019 (table 1). Online supplemental figure 1 summarises the data process.

Table 1.

General practitioner turnover rates between 2007 and 2019

| Year | N practices | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | 25th percentile | 75th percentile |

| 2007 | 8085 | 6.9 | 18.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2008 | 8053 | 7.5 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2009 | 8077 | 9.2 | 20.3 | 0.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 11.1 |

| 2010 | 8058 | 9.4 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 11.8 | 0.0 | 11.8 |

| 2011 | 8009 | 10.5 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 15.4 |

| 2012 | 7924 | 10.8 | 20.2 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 16.7 |

| 2013 | 7809 | 11.6 | 19.3 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 18.2 |

| 2014 | 7629 | 12.0 | 19.9 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 18.2 |

| 2015 | 7404 | 9.4 | 17.4 | 0.0 | 14.5 | 0.0 | 14.5 |

| 2016 | 7211 | 9.4 | 18.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 14.3 |

| 2017 | 6963 | 9.6 | 17.2 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 15.4 |

| 2018 | 6757 | 10.3 | 17.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 16.7 |

| 2019 | 6598 | 9.1 | 16.0 | 0.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 14.3 |

Overall, half of the practices had zero turnover rate within each year of analysis. Over time, turnover rates increased during the study window; in particular, in 2009, the 75th percentile corresponded to an 11% rate and this had increased to 14% in 2019. However, the increase was not linear as the peak occurred in 2013–2014 when the 75th percentile of turnover corresponded to 18%. Summary statistics for turnover rates over time are reported in table 1 and by violin plots in online supplemental figure 2.

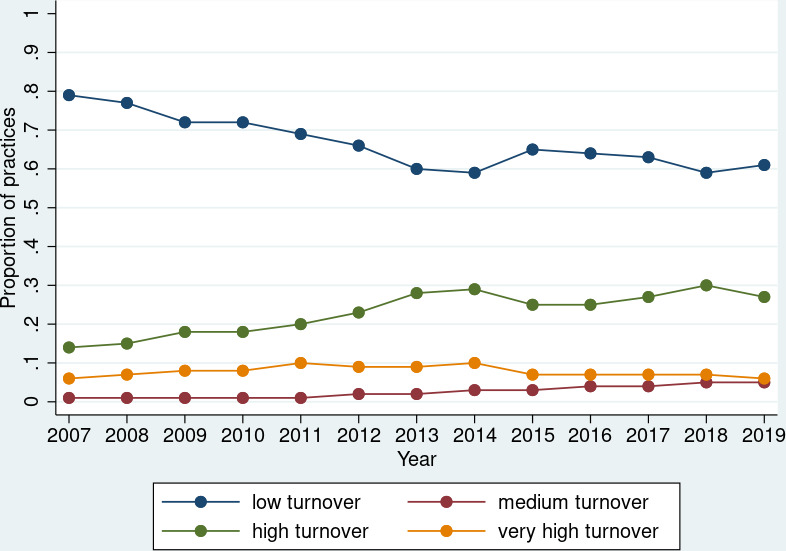

Between 2007 and 2019 the proportion of practices with low turnover (equal to 0%, meaning that no GP left the practice that year) decreased from 79% (in 2007) to 61% (in 2019), whereas the proportion of practices with medium turnover rates (below 10%) slightly increased from 1% in 2007 to 5% in 2009. Overall, 14% of the practices had high turnover (corresponding to 10%–40%) in 2007 a share that increased to 27% in 2019. Approximately 8% of the practices showed very high turnover (above 40%) during the entire time window (figure 1, table 2).

Figure 1.

Proportion of practices with low, medium, high and very high turnover over time. The proportion of practices on y-axis has not been multiplied by 100.

Table 2.

Proportion of practices with low, medium, high and very high turnover rates over time

| Year | N practices | N practices with low turnover | Practices with low turnover (%) | N practices with medium turnover | Practices with medium turnover (%) | N practices with high turnover | Practices with high turnover (%) | N practices with very high turnover | Practices with very high turnover (%) |

| 2007 | 8075 | 6419 | 79.5 | 71 | 0.9 | 1104 | 13.7 | 481 | 5.96 |

| 2008 | 8053 | 6208 | 77.1 | 95 | 1.2 | 1201 | 14.9 | 549 | 6.82 |

| 2009 | 8077 | 5850 | 72.4 | 117 | 1.4 | 1448 | 17.9 | 662 | 8.20 |

| 2010 | 8056 | 5817 | 72.2 | 107 | 1.3 | 1453 | 18.0 | 679 | 8.43 |

| 2011 | 8008 | 5538 | 69.2 | 90 | 1.1 | 1588 | 19.8 | 792 | 9.89 |

| 2012 | 7924 | 5218 | 65.9 | 127 | 1.6 | 1858 | 23.4 | 721 | 9.10 |

| 2013 | 7808 | 4713 | 60.4 | 192 | 2.5 | 2171 | 27.8 | 732 | 9.38 |

| 2014 | 7629 | 4482 | 58.7 | 199 | 2.6 | 2200 | 28.8 | 748 | 9.80 |

| 2015 | 7404 | 4809 | 65.0 | 217 | 2.9 | 1863 | 25.2 | 515 | 6.96 |

| 2016 | 7211 | 4647 | 64.4 | 256 | 3.6 | 1811 | 25.1 | 497 | 6.89 |

| 2017 | 6963 | 4359 | 62.6 | 257 | 3.7 | 1884 | 27.1 | 463 | 6.65 |

| 2018 | 6757 | 3975 | 58.8 | 310 | 4.6 | 2016 | 29.8 | 456 | 6.75 |

| 2019 | 6597 | 4049 | 61.4 | 355 | 5.4 | 1808 | 27.4 | 385 | 5.84 |

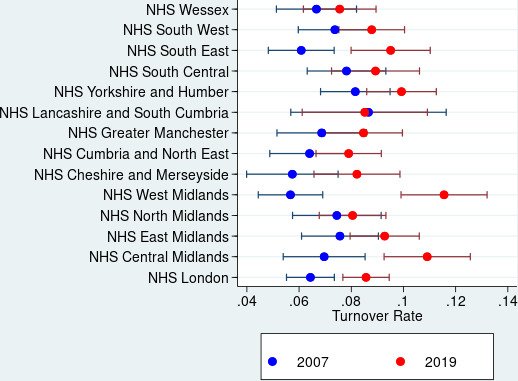

Turnover rates showed great variation across regions. When regional turnover rates were compared at the beginning and end of the study window, all the NHS regions had an increase in turnover rates (2007 vs 2019) (figure 2). NHS England Midlands and East (West Midlands) had the largest increase in turnover rate (on average 6%), from 6% in 2007 to 12% in 2019; whereas NHS England Lancashire and South Cumbria had nearly no increase in turnover (on average 0%) (figure 2). For all the regions, trends of turnover were not always consistently increasing but demonstrated peaks around 2013–2014.

Figure 2.

Comparison of general practitioners turnover rate according to National Health Service (NHS) region 2007 versus 2019. The proportion of practices on y-axis has not been multiplied by 100.

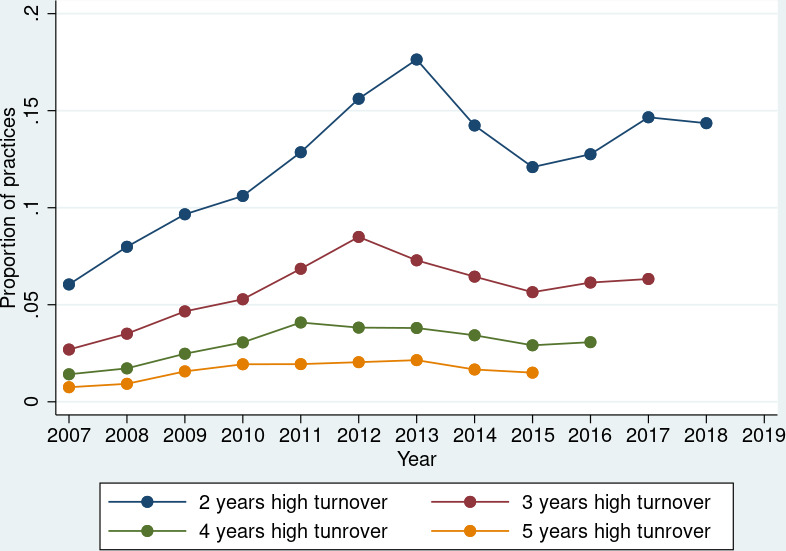

Finally, when examining persistent high turnover over time (>10%), findings revealed that, between 2007 and 2013, there had been a steady increase in the proportion of practices with persistent high turnover either for 2–3 consecutive years (temporary situation) or for 4–5 consecutive years (continuing problem). Practices with high turnover over 2 years, for example, increased from 6.0% in 2007 to 17.6% in 2013, before decreasing to 14.4% in 2018 (figure 3, online supplemental table 4).

Figure 3.

Proportion of practices with persistent high turnover rates (≥10%) over 2, 3, 4 and 5-year window. The proportion of practices on y-axis has not been multiplied by 100.

Predictors of GPs turnover

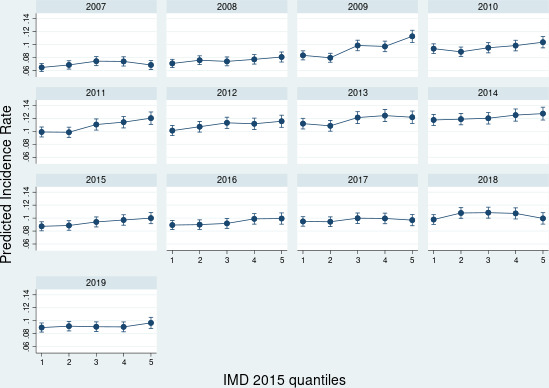

The statistical analyses investigating predictors of GPs turnover revealed that area-deprivation of a practice and year were associated with turnover rate. In particular, practices in the most deprived locations had a greater risk of higher turnover compared with practices in the least deprived areas (IRR 1.09; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.13); and every year in the study window was associated with an increasing turnover rate compared with 2007 (table 3), with 2013 and 2014 associated with the highest turnover rates compared with 2007 (IRR 1.67; 95% CI 1.59 to 1.77 and IRR 1.74; 95% CI 1.64 to 1.83) (table 3 and figure 4).

Table 3.

Predictors of general practitioner turnover rates (primary analysis)

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| IMD | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | Reference | |

| 2 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05) | 0.368 |

| 3 | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.11) | 0.000 |

| 4 | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.13) | 0.000 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1.12 (1.08 to 1.16) | 0.000 |

| 2007 | Reference | |

| 2008 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.15) | 0.011 |

| 2009 | 1.33 (1.26 to 1.41) | 0.000 |

| 2010 | 1.37 (1.29 to 1.45) | 0.000 |

| 2011 | 1.54 (1.46 to 1.63) | 0.000 |

| 2012 | 1.56 (1.48 to 1.65) | 0.000 |

| 2013 | 1.67 (1.59 to 1.77) | 0.000 |

| 2014 | 1.74 (1.64 to 1.83) | 0.000 |

| 2015 | 1.33 (1.26 to 1.41) | 0.000 |

| 2016 | 1.34 (1.26 to 1.41) | 0.000 |

| 2017 | 1.39 (1.31 to 1.47) | 0.000 |

| 2018 | 1.49 (1.41 to 1.58) | 0.000 |

| 2019 | 1.31 (1.24 to 1.39) | 0.000 |

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; IRR, incidence rate ratios.

Figure 4.

Predicted probabilities of general practitioner turnover according to quantiles of social deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), 2015) and year. The proportion of practices on y-axis has not been multiplied by 100.

Sensitivity analyses

Results from sensitivity analyses confirmed the main findings. This was the case when the analysis was restricted to practices active for the entire time window; or when practices with APMS contract were excluded; or when a random effect model for NHS region was fitted (table 4). When the time-window included only practices between 2015 and 2019 and additional variables were included in the statistical model, area-practice deprivation (IRR 1.08; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.13, practices located in most deprived areas vs least deprived areas), proportion of salaried GPs (IRR 1.69; 95% CI 1.59 to 1.79), and year 2018 compared with 2015 (IRR 1.12; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.18) were all significantly associated with higher turnover; whereas lower workload, as expressed by the FTE per 1000 patients ratio, was associated with lower turnover rate (IRR 0.84; 95% CI 0.78 to 0.90) (table 5).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses

| Practice active for the entire time-window | Excluding practices with APMS contract | Random-effect model with NHS region as random effect | ||||

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| IMD | ||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | Reference | |||||

| 2 | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05) | 0.386 | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 0.254 | 1.02 (0.95 to 1.09) | 0.583 |

| 3 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.11) | 0.000 | 1.07 (1.04 to 1.11) | 0.000 | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.15) | 0.031 |

| 4 | 1.08 (1.05 to 1.12) | 0.000 | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.13) | 0.000 | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 0.007 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.13) | 0.000 | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.15) | 0.000 | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.18) | 0.004 |

| 2007 | Reference | |||||

| 2008 | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.12) | 0.080 | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.14) | 0.015 | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) | 0.140 |

| 2009 | 1.31 (1.23 to 1.39) | 0.000 | 1.33 (1.26 to 1.41) | 0.000 | 1.34 (1.20 to 1.50) | 0.000 |

| 2010 | 1.35 (1.27 to 1.43) | 0.000 | 1.35 (1.28 to 1.43) | 0.000 | 1.36 (1.22 to 1.52) | 0.000 |

| 2011 | 1.53 (1.44 to 1.62) | 0.000 | 1.52 (1.44 to 1.61) | 0.000 | 1.53 (1.37 to 1.70) | 0.000 |

| 2012 | 1.56 (1.47 to 1.65) | 0.000 | 1.55 (1.46 to 1.64) | 0.000 | 1.57 (1.41 to 1.74) | 0.000 |

| 2013 | 1.65 (1.56 to 1.75) | 0.000 | 1.65 (1.57 to 1.75) | 0.000 | 1.68 (1.51 to 1.86) | 0.000 |

| 2014 | 1.70 (1.61 to 1.80) | 0.000 | 1.73 (1.63 to 1.82) | 0.000 | 1.74 (1.56 to 1.93) | 0.000 |

| 2015 | 1.31 (1.23 to 1.39) | 0.000 | 1.31 (1.24 to 1.39) | 0.000 | 1.37 (1.22 to 1.53) | 0.000 |

| 2016 | 1.31 (1.24 to 1.39) | 0.000 | 1.31 (1.24 to 1.39) | 0.000 | 1.37 (1.22 to 1.53) | 0.000 |

| 2017 | 1.40 (1.32 to 1.48) | 0.000 | 1.39 (1.31 to 1.47) | 0.000 | 1.40 (1.25 to 1.57) | 0.000 |

| 2018 | 1.53 (1.44 to 1.61) | 0.000 | 1.49 (1.41 to 1.57) | 0.000 | 1.49 (1.34 to 1.67) | 0.000 |

| 2019 | 1.33 (1.26 to 1.41) | 0.000 | 1.31 (1.23 to 1.38) | 0.000 | 1.33 (1.18 to 1.49) | 0.000 |

Predictors of general practitioner turnover rates: (i) restricting the analysis to practices active for the entire time-window; (ii) excluding practices with APMS contract; (iii) random-effect model with NHS region as random effect.

APMS, Alternative Provider Medical Service; IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; IRR, incidence rate ratios; NHS, National Health Service.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analyses

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| IMD | ||

| 1 (least deprived) | Reference | |

| 2 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.063 |

| 3 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 0.012 |

| 4 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 0.013 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.13) | 0.004 |

| Proportion of salaried GPs | 1.69 (1.59 to 1.79) | 0.000 |

| FTE per 1000 patients ratio | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) | 0.000 |

| 2015 | Reference | |

| 2016 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.05) | 0.845 |

| 2017 | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.09) | 0.215 |

| 2018 | 1.12 (1.07 to 1.18) | 0.000 |

| 2019 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) | 0.504 |

Predictors of GPs turnover restricting the time-window to 2015–2019 and adding ‘proportion of salaried GPs’ and ‘FTE per 1000 patients ratio’ to the model.

FTE, full-time-equivalent; GP, general practitioner; IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation; IRR, incidence rate ratios.

Discussion

Main findings

For the first time, rather than intention to leave, this study describes levels of GPs turnover over a 12-year window (2007–2019) and its variation by geographical regions in English primary care. In addition, it also reports on practice-area social deprivation and practice staffing relative to patient lists that were associated with higher or lower levels of GPs turnover, respectively.

In the backdrop of a trend towards fewer and larger general practices,22 our findings revealed that turnover rates increased over the study period, although overall changes were small. Interestingly, turnover rates were the highest during 2013–2014. Over time, the proportion of practices with high turnover increased by 13% and those with very high turnover remained at the same level (around 8%). The majority of NHS regions experienced a rise in turnover between 2007 and 2019, which was greater in some regions than others. For instance, NHS England West Midlands was the region worst affected. Results also showed that, over time, there was a rising number of practices with persistent high turnover for at least five consecutive years, indicative of a continuing problem for these practices. However, this was not associated with practice-level deprivation (results not shown). Finally, there was a significant association between practice area social deprivation and levels of turnover rates. Specifically, practices located in the most deprived areas were associated with the likelihood of higher GP turnover compared with practices located in the least deprived areas.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study has several strengths. First, it quantified and described GPs’ actual turnover rather than ‘intentions to leave’ usually reported in existing studies.2 23 Second, it used two national administrative datasets, regularly updated and monitored by NHS Digital and the RxS/NHS ODS, which have the advantage of including everyone rather than only respondents to a survey, therefore they might be less prone to bias. Third, the study provided rates for a 12-year window and across regions of England. Fourth, the approach employed to calculate turnover rates, used the exact dates when a GP joined and left a practice, therefore more accurate than using aggregate data.10 Fifth, it presented methodological advances in combining multiple data sources containing information about the primary care workforce and historical data of individual GPs’ characteristics.

Limitations of the study need to be acknowledged as well. Despite the fact the workforce data provide a wealth of information on practices characteristics, the main analyses performed in the study included only basic variables (such as practice area social deprivation and year). This was due to NHS Digital employing a revised methodology to calculate some variables (such as GPs’ FTE) from 2015, therefore these data are not comparable with previous years. In addition, it was not possible to have detailed information on individual GP demographics (age and gender) and their employment model from the GP workforce datasets, therefore all the rates presented are combined for GP partners and salaried GPs. CIs for the proportions are not reported since the sample is large and there is very little uncertainty around the estimates. Hence, these would add complexity but little to no new information. Finally, it was not possible to distinguish between those GPs who moved to a different practice, retired or left primary care completely. Nevertheless, joiners’ and retention rates have also been provided (online supplemental material) to give a comprehensive description of the GPs workforce behaviour of joining, staying or leaving a practice.

Comparison with other studies

Studies examining GP turnover rates in England are scarce and relate to the early 90s.10 24 Compared with Taylor and Leese,10 turnover rates are slightly higher in our study, but this can be attributed to the different time-window analysed or to differences in the methodology used, such as combining multiple data sources, using the exact date a GP has joined or left a practice and including all types of working patterns rather than those GPs practicing full time only.10 Similar to their findings is the variation of turnover by region and its association with social deprivation.10 Increasing turnover and regional variation have also been found across NHS Trusts in England for other healthcare professionals.25 Our findings also need to be evaluated in the context of rates of intentions to leave direct patient care within 5 years, as reported in national GP surveys.2 We cannot directly compare the rates we report and those from the surveys, since we cannot quantify those who leave direct patient care, only practice turnover, and we measure that annually, not over 5 years. However, there was discrepancy in trends, with ‘intention to leave’ rates increasing from 19.4% in 2005 to 39% in 2017, and we would have expected a much larger increase in turnover if the intentions reported were fully followed through. Alternatively, perhaps there is an imminent large increase in turnover expected by 2022.

Interpretation of findings and implication for practice

Findings from our study have revealed that there was an increase in GP turnover over the last decade. This trend may be partially explained by the rising number of GPs intending to leave their profession or having a career break,2 23 although there was a discrepancy in rates as previously described. Burnout is considered a key factor contributing to this intention,26 known to be driven by increasing workload through patients with complex needs,27 although the link to turnover is tenuous.28 Other factors relevant to turnover include: lack of or reduced job satisfaction,8 23 dissatisfaction with the ‘amount of responsibility given’,2 ‘physical working conditions’2 and time spent on ‘unimportant tasks’.8 The reasons behind the peak of turnover in 2013–2014 are unclear; this coincides with the introduction of the APMS contract, but we could not confirm causality.

Existing literature highlights that GPs often find managing patients in areas of socioeconomic deprivation a challenge due to the higher prevalence of multimorbidity and the associated healthcare needs.29–31 The higher turnover rates observed in more deprived areas might also be related to differences in the distribution of GP or other healthcare professional workforce, though it is difficult to determine whether these differences are the cause or consequence of higher GP turnover.

Regional variations in turnover might be due to different levels of social deprivation across the regions and varying health services’ pressures. Whereas, the persistent high turnover experience by a number of practices, indicative of a continuing and unresolved problem within the practice or area rather than temporary situation, might be associated with practices experiencing problems with recruitment and retention for specific reasons.10 There is also variation in the characteristics of the GPs across regions, with some regions being served by older or overseas qualified GPs, who may be more mobile.32

High or increasing GP turnover is a concern for the entire healthcare system, especially considering existing difficulties in replacing retiring GPs.32 Recently, the ReGROUP project concluded that policies and strategies to address the existing healthcare workforce crisis in primary care and maximise retention of GPs should facilitate sustainable GP workload and contractual requirements, as well as the need for personal and professional support; in addition to target areas which influence job satisfaction and work-life balance.33

Conclusions

We observed a small overall increase in GP turnover in the last decade across the whole of England, supporting previous local investigations and national surveys—although that increase was not linear, with a turnover peak in 2013–2014, coinciding with the introduction of the APMS contract. Greater attention to GP turnover is needed, particularly in the most severely deprived areas, to address the complex health needs of the population living in these areas and avoid the exacerbation of health inequalities. Moreover, there is a large cost associated with GP turnover and practices with very high persistent turnover need to be further investigated. Finally, targeted policies and strategies need to be developed and tested to diminish its occurrence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Bowercpcman, @dataevan

Contributors: PB, KC, JR, MS, AE, SS, Y-SL, SJG and EK secured funding for the study. RP, YSL and EK designed the analyses. RP performed the statistical analyses with input from PB, KC, JR, MS, AE, SS, Y-SL, SJG and EK. RP drafted the paper and PB, KC, JR, MS, AE, SS, Y-SL, SJG and EK critically revised it. RP is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This project has been funded by the Health Foundation as part of the Efficiency Research Programme (AIMS ID: 1318316). All decisions concerning analysis, interpretation and publication are made independently from the funder.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The GP workforce and the GPs-by-general practices data are freely available from the NHS Digital and TRUD websites, respectively.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.RCGP . New League table reveals GP shortages across England, as patients set to wait week or more to see family doctor on 67 M occasions, 2015. Available: https://healthwatchtrafford.co.uk/news/new-league-table-reveals-gp-shortages-across-england-as-patients-set-to-wait-week-or-more-to-see-family-doctor-on-67m-occasions/ [Accessed 22 Jul 2020].

- 2.Gibson J, Sutton M, Spooner S. University of Manchester: Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System Manchester Centre for Health Economics. In: Ninth national GP Worklife survey, 2018: 36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin S, Davies E, Gershlick B. Under pressure: What the Commonwealth Fund’s 2015 international survey of general practitioners means for the UK. Health Foundation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen X, Jiang H, Xu H, et al. The global prevalence of turnover intention among general practitioners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract 2020;21:246. 10.1186/s12875-020-01309-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes H, Gibson J, Fitzpatrick B, et al. Working lives of GPs in Scotland and England: cross-sectional analysis of national surveys. BMJ Open 2020;10:e042236. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B. A critical moment: NHS staffing trends, retention and attrition, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt J. New deal for general practice. Jeremy Hunt sets out the first steps in a new deal for GPs, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dale J, Potter R, Owen K, et al. Retaining the general practitioner workforce in England: what matters to GPs? A cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:140. 10.1186/s12875-015-0363-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fletcher E, Abel GA, Anderson R, et al. Quitting patient care and career break intentions among general practitioners in South West England: findings of a census survey of general practitioners. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015853. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor DH, Leese B. General practitioner turnover and migration in England 1990-94. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1070–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy A, Pollack CE, Asch DA, et al. The effect of primary care provider turnover on patient experience of care and ambulatory quality of care. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1157–62. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan VS, Burman M, McDonell MB, et al. Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:226–33. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40135.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, et al. Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:742–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1879–85. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchbinder SB, Wilson M, Melick CF, et al. Primary care physician job satisfaction and turnover. Am J Manag Care 2001;7:701–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1826–32. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchan J. Reviewing the benefits of health workforce stability. Hum Resour Health 2010;8:29. 10.1186/1478-4491-8-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hann M, Reeves D, Sibbald B. Relationships between job satisfaction, intentions to leave family practice and actually leaving among family physicians in England. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:499–503. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NHS Digital . Joiners and leaver rates with stability index 2016 -2018. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/find-data-and-publications/supplementary-information/2019-supplementary-information-files/leavers-and-joiners/joiners-and-leaver-rates-with-stability-index-2016-2018

- 20.NHS Digital . General practice workforce. Available: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-and-personal-medical-services

- 21.NHS Digital TRUD . NHS Ods Weekly prescribing-related data. Available: https://isd.digital.nhs.uk/trud3/user/guest/group/0/pack/5

- 22.PULSE . Average practice list size grows by more than 2% in just eight months. Available: https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/practice-closures/average-practice-list-size-grows-by-more-than-2-in-just-eight-months/

- 23.Gibson J, Checkland K, Coleman A. Eighth national GP Worklife survey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor DH, Leese B. Recruitment, retention, and time commitment change of general practitioners in England and Wales, 1990-4: a retrospective study. BMJ 1997;314:314. 10.1136/bmj.314.7097.1806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B. Rising pressure: the NHS workforce challenge 2017.

- 26.Cheshire A, Ridge D, Hughes J, et al. Influences on GP coping and resilience: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e428–36. 10.3399/bjgp17X690893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen AF, Nørøxe KB, Vedsted P. Influence of patient multimorbidity on GP burnout: a survey and register-based study in Danish general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:e95–101. 10.3399/bjgp20X707837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen AF, Andersen CM, Olesen F, et al. Risk of burnout in Danish GPs and exploration of factors associated with development of burnout: a two-wave panel study. Int J Family Med 2013;2013:1–8. 10.1155/2013/603713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eley E, Jackson B, Burton C, et al. Professional resilience in GPs working in areas of socioeconomic deprivation: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:e819–25. 10.3399/bjgp18X699401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Brien R, Wyke S, Guthrie B, et al. An 'endless struggle': a qualitative study of general practitioners' and practice nurses' experiences of managing multimorbidity in socio-economically deprived areas of Scotland. Chronic Illn 2011;7:45–59. 10.1177/1742395310382461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long L, Moore D, Robinson S, et al. Understanding why primary care doctors leave direct patient care: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2020;10:e029846. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esmail A, Panagioti M, Kontopantelis E. The potential impact of Brexit and immigration policies on the GP workforce in England: a cross-sectional observational study of GP qualification region and the characteristics of the areas and population they served in September 2016. BMC Med 2017;15:191. 10.1186/s12916-017-0953-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chilvers R, Richards SH, Fletcher E, et al. Identifying policies and strategies for general practitioner retention in direct patient care in the United Kingdom: a RAND/UCLA appropriateness method panel study. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:130. 10.1186/s12875-019-1020-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-049827supp001.pdf (536.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The GP workforce and the GPs-by-general practices data are freely available from the NHS Digital and TRUD websites, respectively.