Abstract

Objective

This analysis evaluated efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a Janus-associated kinase 1-preferential inhibitor, in methotrexate (MTX)-naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with multiple poor prognostic factors (PPFs).

Methods

This was a post hoc analysis of the phase III, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, FINCH 3 study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02886728). Patients received once-daily oral filgotinib 200 or 100 mg plus once-weekly oral MTX ≤20 mg (FIL200 + MTX and FIL100 + MTX), filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (FIL200), or oral MTX monotherapy (MTX-mono) for up to 52 weeks. PPFs investigated were seropositivity for rheumatoid factor or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, high-sensitivity C reactive protein (CRP) ≥4 mg/L, Disease Activity Score in 28 joints with CRP (DAS28(CRP)) >5.1, and presence of erosions. Filgotinib efficacy and safety in patients with all four PPFs at baseline were explored versus MTX-mono within this subgroup and compared informally with the overall population.

Results

Of 1249 patients in FINCH 3, 510 (40.8%) had all PPFs. Efficacy of FIL200 + MTX among these patients was comparable to the overall population, with higher rates of 20%/50%/70% improvement from baseline by American College of Rheumatology criteria, DAS28(CRP) <2.6, and remission; greater improvement in physical function and pain; and better inhibition of structural damage relative to MTX-mono. FIL100 + MTX and FIL200 were not consistently more efficacious versus MTX-mono. Safety of filgotinib in patients with PPFs was comparable to the overall population; no new safety signals were observed.

Conclusion

FIL200 + MTX efficacy and safety in patients with multiple PPFs were similar to the overall population.

Keywords: arthritis, rheumatoid, therapeutics, antirheumatic agents

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Seropositivity for rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, elevated acute-phase reactant levels, persistent moderate-to-high disease activity, and presence of early erosions are associated with severe disease and risk for disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

The 2019 EULAR management guidelines for RA recommend early treatment escalation for patients with these poor prognostic factors (PPFs) who have inadequate response to first-line therapy.

What does this study add?

Filgotinib efficacy and safety in patients with RA with PPFs were consistent with the overall RA phase III study population and previous studies.

Treatment with filgotinib 200 mg once daily in combination with methotrexate (MTX) resulted in higher rates of positive clinical, functional and structural outcomes compared with MTX alone in this population.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

Efficacy of filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX is not impaired in patients with PPFs.

Filgotinib may be an alternative treatment option for patients with RA who have PPFs, especially those not responding to standard treatment such as MTX.

Introduction

The 2019 EULAR guidelines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) recommend methotrexate (MTX) in combination with short-term glucocorticoids, unless contraindicated, as the first treatment strategy on diagnosis of RA.1 According to the treat-to-target strategy, treatment should be adjusted for patients who do not achieve 50% improvement after approximately 3 months, as they are unlikely to achieve desired treatment targets of remission or low disease activity within 6 months.1 The choice of second-line treatment is stratified by the presence of poor prognostic factors (PPFs) associated with rapid disease progression, including elevated acute-phase reactant levels; high swollen joint count; seropositivity—especially with high titres—for rheumatoid factor (RF) or anticyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies; presence of early erosions; and persistent moderate or high disease activity.1 Treatment escalation to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or targeted synthetic DMARD (tsDMARD) therapy is recommended for patients who present with any of these PPFs and do not achieve their treatment target; in patients without these factors, another conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) strategy could be considered after first-line treatment failure.1

The EULAR guidelines acknowledge evidence supporting this strategy is limited, and the research agenda put forward in this EULAR-endorsed document includes treatment outcomes in patients with and without PPFs.1 Furthermore, although these PPFs historically predict radiographic progression of joint damage in patients treated with csDMARDs or tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors,2–5 data are relatively sparse regarding their effect on radiographic outcomes and physical function following first-line treatment with non-TNF bDMARDs or tsDMARDs such as Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Data are needed on efficacy of bDMARDs or tsDMARDs versus csDMARDs for clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients with PPFs.

Filgotinib is a once-daily oral, JAK1-preferential inhibitor with demonstrated efficacy and a favourable safety profile in adults with moderately to severely active RA.6–11 The phase III, randomised, active-controlled FINCH 3 trial (NCT02886728), which evaluated filgotinib efficacy and safety in MTX-naive patients with RA, included patients with at least one marker or risk factor for rapidly progressive disease.11 Here, we assessed filgotinib efficacy and safety in the subgroup of patients with all of four PPFs present at baseline.

Methods

Study design, patients and treatments

The FINCH 3 trial was previously described in detail.11 Briefly, MTX-naive adult patients with moderately to severely active RA were randomised 2:1:1:2 to receive oral filgotinib 200 mg once daily plus oral MTX ≤20 mg once weekly, oral filgotinib 100 mg plus oral MTX, oral filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy or oral MTX monotherapy for up to 52 weeks. Patients enrolled in FINCH 3 were required to have ≥1 of the following at screening: seropositivity for RF or anti-CCP antibodies (determined by the central laboratory); serum high-sensitivity C reactive protein (hsCRP) ≥4 mg/L; or ≥1 documented joint erosion on radiographs of the hands, wrists or feet by central reading. For this post hoc analysis, PPFs were defined as seropositivity for RF and/or anti-CCP antibodies, serum hsCRP ≥4 mg/L, disease activity score in 28 joints with C reactive protein (DAS28(CRP)) >5.1 (ie, high disease activity) and erosion score >0 at baseline. These parameters were chosen because they are recognised PPFs that are applicable in the FINCH 3 study population and compatible with the eligibility criteria.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by all local institutional review boards or ethics committees. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided consent to participate.

Assessments and endpoints

The schedule of assessments was previously reported.11 Briefly, clinical assessments and patient questionnaires were administered and adverse events (AEs) were recorded at each study visit. Radiographs of bilateral hands, wrists and feet obtained at screening, week 24 and week 52/end-of-treatment were scored by two central readers blinded to order of films, patient characteristics and treatment group; in case of disagreement, a third reader adjudicated the scores.

Efficacy outcomes evaluated in this post hoc analysis included proportion of patients with 20% improvement from baseline in American College of Rheumatology core criteria (ACR20) at week 24, the primary outcome for FINCH 3; ACR20/50/70 response rates through week 52 were also assessed.12 Additional clinical outcomes were change from baseline Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and proportions of patients who achieved DAS28(CRP) <2.6 or ≤3.2; disease remission was defined as CDAI≤2.8, SDAI≤3.3 or Boolean remission, and low disease activity was defined as CDAI≤10 or SDAI≤11 through week 52.13–15 Patient-reported outcomes included change from baseline in Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and change from baseline in the Subject’s Pain Assessment.16 17 Radiographic progression was assessed as change from baseline in van der Heijde modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 24 and week 52 and proportion of patients with change from baseline mTSS≤0 at weeks 24 and 52 (details are present in online supplemental methods).18

rmdopen-2021-001621supp001.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

Safety was evaluated from AEs, coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities V.22.0, and graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.4.03; and laboratory safety assessments. Potential major adverse cardiac events and venous thrombotic events were adjudicated centrally, and positively adjudicated events are reported.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy and safety analyses were performed in all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication as previously described.11 No formal hypothesis testing was performed to compare patients with PPFs versus the overall population, and all such comparisons are descriptive. Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed in patients with all four PPFs comparing efficacy across treatments within this risk factor population. Analyses of binary endpoints were performed using Fisher’s exact test for comparisons between each filgotinib dose versus MTX monotherapy; patients with missing data were imputed as non-responders. The number of patients needed to be treated with each dose of filgotinib versus MTX monotherapy for one additional patient to achieve binary endpoints (‘number needed to treat;’ NNT) were determined based on rate differences in each endpoint between patients receiving each filgotinib dose and MTX monotherapy. The 95% CI of the rate difference was based on a normal approximation method with a continuity correction; when the 95% CI of the rate difference spanned 0, the 95% CI of the NNT was not presented. The change from baseline in continuous endpoints was evaluated using a mixed model for repeated measures with treatment, visit, treatment by visit interaction and baseline value included as fixed effects and patient as a random effect; missing data were not imputed. Modifications for the analysis of mTSS change from baseline at week 52 are detailed in online supplemental methods. Selected efficacy and safety analyses were repeated in subgroups of patients with four PPFs with and without baseline glucocorticoid use. Efficacy was also explored in subgroups of patients with disease duration <6 months versus ≥6 months; patients with only three, two or one PPFs; and patients with specific combinations of PPFs. Post hoc analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and nominal p values are presented.

Results

Patients

Of all 1249 patients who were randomised and received study drug, 510 (40.8%) had all four PPFs at baseline; 397 (77.8%) patients with all four PPFs completed study treatment through week 52, compared with 78.1% of the overall population (online supplemental figure 1). As expected, and partly by definition, patients with all four PPFs had greater structural damage (mean mTSS: 17.9 vs 13.3), poorer functional status (HAQ-DI: 1.76 vs 1.56), higher disease activity (CDAI: 44.3 vs 39.8; SDAI: 47.1 vs 41.5; DAS28(CRP): 6.3 vs 5.7; hsCRP: 27.9 vs 17.5 mg/L) and higher rate of seropositivity for RF (90.6% vs 67.9%), anti-CCP antibodies (92.4% vs 68.5%) or both (82.9% vs 59.6%) compared with the overall population (table 1). In total, 44.9% of patients with four PPFs had concurrent oral glucocorticoid therapy at baseline, compared with 39.6% in the overall population (table 1). Baseline characteristics were generally similar between patients with four PPFs with versus without baseline glucocorticoid use except for longer mean duration of RA (3.3 vs 1.7 years), greater frequency of csDMARD use (21.4% vs 15.3%) and concurrent antimalarial use (13.5% vs 6.4%) and higher mean baseline mTSS score (21.8 vs 14.7).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of patients with all four poor prognostic factors and the overall study population

| Patients with four poor prognostic factors | Overall | |||||

| FIL 200 mg + MTX n=172 |

FIL 100 mg + MTX n=85 |

FIL 200 mg n=87 |

MTX n=166 |

Total n=510 |

Total N=1249 |

|

| Age, years | 51±12.9 | 53±12.9 | 50±12.8 | 53±12.9 | 52±12.9 | 53±13.6 |

| Female, n (%) | 133 (77.3) | 65 (76.5) | 67 (77.0) | 128 (77.1) | 393 (77.1) | 961 (76.9) |

| RA duration, years | 1.8±3.40 | 2.8±5.50 | 2.4±6.27 | 2.7±6.16 | 2.4±5.29 | 2.2±4.97 |

| Median (min, max) | 0.4 (0, 26.8) | 0.6 (0.1, 31.7) | 0.3 (0, 47.2) | 0.6 (0, 52.3) | 0.5 (0, 52.3) | 0.4 (0, 52.3) |

| ≤6 months, n (%) | 89 (51.7) | 41 (48.2) | 50 (57.5) | 78 (47.0) | 258 (50.6) | 686 (54.9) |

| 6 months–1 year, n (%) | 22 (12.8) | 13 (15.3) | 7 (8.0) | 24 (14.5) | 66 (12.9) | 140 (11.2) |

| ≥1 year, n (%) | 61 (35.5) | 31 (36.5) | 30 (34.5) | 64 (38.6) | 186 (36.5) | 423 (33.9) |

| Prior non-MTX csDMARD use, n (%) | 25 (14.5) | 17 (20.0) | 15 (17.2) | 35 (21.1) | 92 (18.0) | 222 (17.8) |

| Prior exposure to MTX, n (%) | 12 (7.0) | 7 (8.2) | 9 (10.3) | 10 (6.0) | 38 (7.5) | 82 (6.6) |

| Concurrent oral glucocorticoid use, n (%) | 61 (35.5) | 45 (52.9) | 45 (51.7) | 78 (47.0) | 229 (44.9) | 494 (39.6) |

| Glucocorticoid dose, mg/day | 6.9±2.44 | 7.2±2.59 | 6.5±2.09 | 6.3±2.31 | 6.7±2.37 | 6.6±2.43 |

| Concurrent antimalarial use, n (%) | 12 (7.0) | 12 (14.1) | 6 (6.9) | 19 (11.4) | 49 (9.6) | 118 (9.4) |

| Seropositivity | ||||||

| RF, n (%) | 162 (94.2) | 75 (88.2) | 77 (88.5) | 148 (89.2) | 462 (90.6) | 848 (67.9) |

| Anti-CCP, n (%) | 162 (94.2) | 76 (89.4) | 76 (87.4) | 157 (94.6) | 471 (92.4) | 855 (68.5) |

| RF and anti-CCP, n (%) | 152 (88.4) | 66 (77.6) | 66 (75.9) | 139 (83.7) | 423 (82.9) | 744 (59.6) |

| hsCRP, mg/L | 31.6±31.3 | 28.0±28.5 | 23.3±24.6 | 26.3±27.1 | 27.9±28.5 | 17.5±25.0 |

| mTSS erosions >0, n (%) | 172 (100) | 85 (100) | 87 (100) | 166 (100) | 510 (100) | 1173 (93.9) |

| SJC66 | 20±11.4 | 19±10.8 | 19±10.8 | 18±10.1 | 19±10.8 | 16.0±9.6 |

| TJC68 | 30±14.3 | 29±13.1 | 28±13.6 | 28±14.3 | 29±14.0 | 26.0±14.0 |

| Pain (VAS) | 73±17.0 | 73±19.0 | 72±16.4 | 73±17.0 | 73±17.2 | 65±21.3 |

| HAQ-DI | 1.73±0.59 | 1.79±0.63 | 1.72±0.69 | 1.81±0.55 | 1.76±0.60 | 1.56±0.634 |

| DAS28(CRP) | 6.4±0.73 | 6.3±0.72 | 6.2±0.67 | 6.3±0.72 | 6.3±0.72 | 5.7±0.99 |

| CDAI | 44.8±12.0 | 45.1±11.1 | 42.7±11.9 | 44.2±11.1 | 44.3±11.5 | 39.8±12.6 |

| SDAI | 47.9±12.3 | 47.9±11.8 | 45.0±11.7 | 46.8±11.8 | 47.1±11.9 | 41.5±13.4 |

| mTSS units* | 13.2±23.1 | 18.1±35.9 | 24.2±44.3 | 19.3±37.2 | 17.9±34.5 | 13.3±26.7 |

Data are shown as mean±SD unless otherwise noted.

*Campaign A.

CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DAS28(CRP), disease activity score in 28 joints with C reactive protein; FIL, filgotinib; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C reactive protein; mTSS, van der Heijde modified total Sharp score; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatic factor; SD, standard deviation; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Efficacy

American College of Rheumatology responses

Compared with the overall study population, patients with four PPFs had similar or numerically higher ACR response rates, although no formal analysis was performed (figure 1A–C). Among patients with four PPFs, treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX versus MTX monotherapy was associated with higher rates (95% CI) of ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses at week 24 (85.5% (79.9% to 91.0%)/70.3% (63.2% to 77.5%)/54.1% (46.3% to 61.8%) vs 74.7% (67.8% to 81.6%)/48.2% (40.3% to 56.1%)/28.3% (21.2% to 35.5%)), as well as weeks 12 and 52 (nominal p<0.05 for all comparisons; figure 1A–C). The ACR20/50/70 response rates were not consistently different in patients receiving filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy relative to MTX monotherapy (figure 1A–C).

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients achieving ACR20/50/70 at (A) week 12, (B) week 24 and (C) week 52. Error bars represent the 95% CI. #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 versus MTX; *nominal p<0.05, **nominal p<0.01, ***nominal p<0.001 versus MTX. ACR20/50/70, 20%/50%/70% improvement from baseline in American College of Rheumatology core criteria; FIL, filgotinib; MTX, methotrexate; PPF, patients with four poor prognostic factors.

Disease activity and remission measures

In both patients with four PPFs and the overall population, achievement of low disease activity at weeks 24 and 52 was more frequent (nominal p<0.05 for all measures) among patients treated with any filgotinib regimen relative to MTX monotherapy (figure 2A). Compared with the overall population, patients with four PPFs achieved DAS28(CRP) <2.6 and all remission measures at similar or numerically higher rates following treatment with filgotinib 200 mg with or without MTX, but at numerically lower rates following treatment with filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or MTX monotherapy, at week 24 (figure 2B, C). Only patients receiving filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX maintained comparable rates of DAS28(CRP) <2.6 and remission relative to the overall population at week 52 (figure 2B, C).

Figure 2.

(A) Proportions of patients with four PPFs (left) and the overall population (right) achieving low disease activity at weeks 24 and 52. (B) Proportions of patients with four PPFs (left) and all FINCH 3 patients (right) achieving DAS28(CRP) <2.6 over time through week 52. (C) Proportions of patients achieving remission defined by CDAI≤2.8, SDAI≤3.3 or Boolean remission criteria at weeks 24 (left) and 52 (right). Error bars represent the 95% CI. ###p<0.001, *nominal p<0.05, **nominal p<0.01, ***nominal p<0.001 versus MTX. CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28(CRP), Disease Activity Score in 28 joints with C reactive protein; FIL, filgotinib; MTX, methotrexate; PPF, patients with four poor prognostic factors; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

The proportion (95% CI) of patients with four PPFs who achieved DAS28(CRP) <2.6, CDAI≤2.8, SDAI≤3.3 or Boolean remission was higher following 24 weeks of treatment with filgotinib 200 mg with MTX (53.5% (45.7% to 61.2%), 27.3% (20.4% to 34.3%), 29.7% (22.5% to 36.8%) or 25.0% (18.2% to 31.8%), respectively) or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (40.2% (29.4% to 51.1%), 19.5% (10.6% to 28.4%), 19.5% (10.6% to 28.4%) or 16.1% (7.8% to 24.4%), respectively) versus MTX monotherapy (21.1% (14.6% to 27.6%), 8.4% (3.9% to 13.0%), 7.2% (3.0% to 11.5%) or 7.2% (3.0% to 11.5%), respectively; nominal p<0.05 for all measures). However, only the response rate for SDAI≤3.3 was greater in patients receiving filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX versus MTX monotherapy (16.5% (8.0% to 24.9%) vs 7.2% (3.0% to 11.5%); figure 2B, C). In contrast, in the overall FINCH 3 population, the proportions of patients achieving DAS28(CRP) <2.6 and remission at week 24 were higher following treatment with any filgotinib regimen relative to MTX monotherapy (figure 2B, C). At week 52, DAS28(CRP) <2.6 and remission rates remained higher in patients with four PPFs receiving filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX versus MTX monotherapy (figure 2B, C). No differences were observed in the response rates for the majority of these measures following treatment with filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy versus MTX monotherapy at week 52 (figure 2B, C).

Improvements from baseline in CDAI (figure 3A) and SDAI (figure 3B) were present at week 12 for patients with four PPFs receiving any filgotinib treatment regimen relative to MTX monotherapy and persisted through week 52 (nominal p<0.05 at weeks 12, 24, and 52). Although no formal analysis was performed, the filgotinib treatment effect appeared comparable or better in patients with four PPFs relative to the overall population (figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Treatment effect of filgotinib regimens versus MTX monotherapy on change from baseline in (A) CDAI and (B) SDAI at weeks 12, 24 and 52. CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; FIL, filgotinib; LSM, least squares mean; MTX, methotrexate; PPF, patients with four poor prognostic factors; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

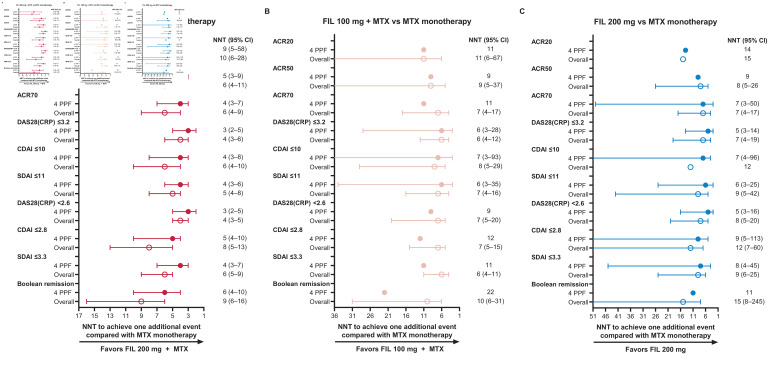

To further explore the clinical benefit of filgotinib treatment in patients with four PPFs, the NNT for one additional patient to achieve treatment endpoints for each dose of filgotinib versus MTX monotherapy was calculated for ACR20/50/70 response, low disease activity, and remission (figure 4). Among patients receiving filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX, the NNT was lower for patients with four PPFs relative to the overall population for all endpoints (ACR20, 9 vs 10; ACR50, 5 vs 6; ACR70, 4 vs 6; DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, 3 vs 4; CDAI≤10, 4 vs 6; SDAI≤11, 4 vs 5; DAS28(CRP) <2.6, 3 vs 4; CDAI≤2.8, 5 vs 8; SDAI≤3.3, 4 vs 6; Boolean remission, 6 vs 9; figure 4A). For CDAI and SDAI low disease activity and remission, NNT was also lower among patients with four PPFs receiving filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy compared with the overall population (DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, 5 vs 7; CDAI≤10, 7 vs 12; SDAI≤11, 6 vs 9; DAS28(CRP) <2.6, 5 vs 8; CDAI≤2.8, 9 vs 12; SDAI≤3.3, 8 vs 9; Boolean remission, 11 vs 15; figure 4B); no consistent differences in NNT between the PPF and overall populations were observed in patients receiving filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Number of patients needed to treat with (A) filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX, (B) filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or (C) filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy versus MTX monotherapy for one additional patient to achieve clinical endpoints. 95% CI of NNT not shown where the 95% CI of the rate difference between FIL and MTX spanned 0. ACR20/50/70, 20%/50%/70% improvement from baseline in American College of Rheumatology core criteria; CDAI, Clinical Disease Activity Index; DAS28(CRP), disease activity score in 28 joints with C reactive protein; FIL, filgotinib; MTX, methotrexate; NNT, number needed to treat; PPF, patients with four poor prognostic factors; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

Physical function

Treatment with any filgotinib regimen versus MTX monotherapy was associated with similar or greater improvement from baseline in physical function and patient-assessed pain among patients with four PPFs relative to the overall population (figure 5A, B). Mean (SD) change from baseline HAQ-DI at week 24 among patients with four PPF was larger following treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX (−1.19 (0.729)), filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (−1.02 (0.691)), or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (−1.00 (0.630)) compared with MTX monotherapy (−0.86 (0.634); nominal p<0.05; figure 5A). This treatment benefit was maintained at week 52 for patients treated with filgotinib 200 mg with or without MTX, but not filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX, relative to MTX monotherapy (figure 5A). Similarly, patient-assessed pain was further decreased from baseline at weeks 24 and 52 in patients treated with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX (mean (SD), −52 (26.3) at week 24) or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (mean (SD), −44 (24.6) at week 24), but not in patients receiving filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (mean (SD), −42 (26.5) at week 24), relative to MTX monotherapy (mean (SD), −39 (27.1) at week 24 (figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Treatment difference versus MTX monotherapy in change from baseline in (A) HAQ-DI and (B) patient pain assessment at weeks 24 and 52. aNot adjusted for multiplicity except where indicated. bAdjusted for multiplicity. FIL, filgotinib; HAQ-DI, health assessment questionnaire-disability index; LS, least squares; MTX, methotrexate; PPF, patients with four poor prognostic factors.

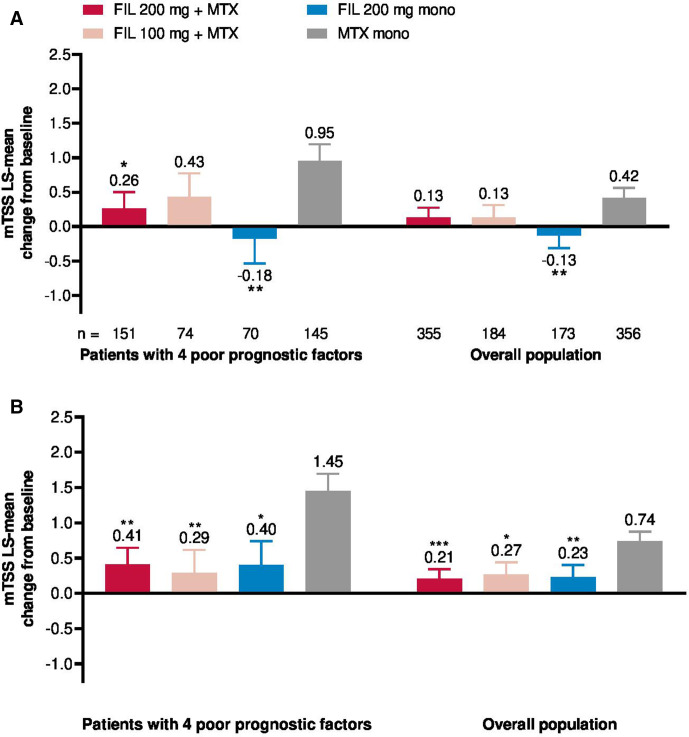

Radiographic progression

Radiographic progression was numerically greater in patients with all four PPFs compared with the overall population (figure 6A, B). Among patients with four PPFs, radiographic progression at week 24 based on least-squares mean (SE) change from baseline mTSS was decreased in patients treated with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX (0.26 (0.240)) or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (−0.18 (0.354)), but not filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (0.43 (0.342)), relative to MTX monotherapy (0.95 (0.244); figure 6A). At week 52, patients had less radiographic progression following treatment with all filgotinib regimens relative to MTX monotherapy (figure 6B). Proportions of patients with no radiographic progression (defined as mTSS≤0) at week 24 are shown in online supplemental table 1 and odds ratios for no radiographic progression at week 52 following treatment with filgotinib versus MTX monotherapy in online supplemental table 2.

Figure 6.

Change in mTSS from baseline at (A) week 24 and (B) week 52. *Nominal p<0.05, **nominal p<0.01. FIL, filgotinib; LS, least squares; mTSS, van der Heijde modified total Sharp score; MTX, methotrexate.

Subgroup analyses

Efficacy in subgroups of patients with four PPFs with and without baseline glucocorticoid use was similar to results in all patients with four PPFs, as shown for ACR20 response and SDAI remission rate at week 24 in online supplemental figure 2. Disease duration ≥6 months versus <6 months had no apparent effect on ACR20 response rate (online supplemental figure 2A); however, while rates of remission by SDAI at week 24 were also similar across filgotinib treatment arms among patients with early disease (<6 months), patients with established disease (≥6 months) had higher SDAI remission rates following treatment with filgotinib 200 mg (regardless of MTX use) versus filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or MTX monotherapy (online supplemental figure 2B).

In exploratory analyses, treatment with filgotinib, especially in combination with MTX, also resulted in higher SDAI remission rates (nominal p<0.05) compared with MTX monotherapy in patients with fewer than four PPFs. Patients treated with filgotinib plus MTX versus MTX monotherapy had higher SDAI remission rates at week 24 across all combinations of three or two PPFs examined (nominal p<0.05), with numerical trends for higher rates of SDAI remission at week 24 in patients receiving filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy versus MTX monotherapy, as well (online supplemental figure 3). Treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX was generally more effective versus filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy only in patients with four PPFs and with the examined combinations of PPFs—particularly among patients with erosions, seropositivity and CRP ≥4; erosions, DAS28(CRP) >5.1, and CRP ≥4; or erosions and CRP ≥4—but not among patients with only three or two PPFs overall (online supplemental figure 3).

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) among patients with four PPFs, including frequencies of all TEAEs, TEAEs of severity grade ≥3, serious TEAEs and TEAEs leading to temporary study treatment interruption or premature discontinuation, were generally similar to those in the overall population and comparable among treatment arms (table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent AEs in patients with four PPFs and the overall population

| FIL 200 mg + MTX | FIL 100 mg + MTX | FIL 200 mg | MTX | |||||

| PPF-4 | Overall | PPF-4 | Overall | PPF-4 | Overall | PPF-4 | Overall | |

| n | 172 | 416 | 85 | 207 | 87 | 210 | 166 | 416 |

| All AEs | 125 (72.7) | 318 (76.4) | 68 (80.0) | 164 (79.2) | 57 (65.5) | 143 (68.1) | 118 (71.1) | 305 (73.3) |

| Grade ≥3 AEs | 17 (9.9) | 50 (12.0) | 15 (17.6) | 26 (12.6) | 6 (6.9) | 18 (8.6) | 15 (9.0) | 40 (9.6) |

| Serious AEs | 8 (4.7) | 26 (6.3) | 9 (10.6) | 13 (6.3) | 7 (8.0) | 17 (8.1) | 15 (9.0) | 28 (6.7) |

| AEs leading to temporary interruption of study drug | 40 (23.3) | 102 (24.5) | 19 (22.4) | 46 (22.2) | 14 (16.1) | 28 (13.3) | 31 (18.7) | 97 (23.3) |

| AEs leading to premature discontinuation of study drug | 12 (7.0) | 28 (6.7) | 8 (9.4) | 13 (6.3) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (2.4) | 13 (7.8) | 25 (6.0) |

| Death* | 0 | 3 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 56 (32.6) | 148 (35.6) | 35 (41.2) | 76 (36.7) | 37 (42.5) | 75 (35.7) | 55 (33.1) | 157 (37.7) |

| Serious infections | 4 (2.3) | 5 (1.2) | 3 (3.5) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (2.4) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (1.9) |

| Opportunistic infections | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| Herpes zoster | 2 (1.2) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (3.4) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.0) |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MACE | 0 | 4 (1.0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| VTE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) |

| Malignancy (excluding NMSC) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.0) |

| NMSC | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| Gastrointestinal perforation | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are presented as n (%).

Only positively adjudicated MACE and VTE are reported.

*The causes of death included lupus myocarditis (possible overlapping systemic autoimmune disease), intracranial aneurysm, interstitial lung disease and sudden cardiovascular death, which occurred 68 days after treatment discontinuation.

AE, adverse event; FIL, filgotinib; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; MTX, methotrexate; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PPF-4, patients with all four poor prognostic factors; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

The TEAEs of special interest were generally similar between patients with four PPFs and the overall population and among treatment arms within each population, with some possible exceptions (table 2). The frequency of infectious TEAEs was higher among patients with PPFs treated with filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy relative to both similarly treated patients in the overall population and patients with PPFs receiving other treatments. Serious infections occurred with higher frequency in patients with four PPFs receiving filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX (2.3%; n=4) or filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (3.5%; n=3) relative to patients in the overall population receiving the same treatment or patients with PPFs treated with filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy (1.1%; n=1) or MTX monotherapy (1.8%; n=3). Other AEs of special interest in patients with PPFs occurred in ≤3 patients receiving any treatment regimen (table 2). Herpes zoster infection occurred at low frequency in all treatment arms: 1.2%, 2.4%, 3.4% and 0.6% of patients receiving filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX, filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX, filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy and MTX monotherapy, respectively.

The overall AE rates were similar in subgroups of patients with four PPFs with and without baseline glucocorticoid use within all treatment arms including MTX monotherapy. Glucocorticoid use was associated with higher frequency of infection within the filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX and filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy treatment arms compared with patients in the same treatment arm not receiving glucocorticoids. The frequency of serious infection was also higher in patients with versus without glucocorticoid use within the filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX (3 (6.7%) with vs 0 without glucocorticoid use) and MTX monotherapy (2 (2.6%) with vs 1 (1.1%) without glucocorticoid use) treatment arms. Other AEs of special interest occurred in fewer than three patients in each glucocorticoid use subgroup.

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of FINCH 3 comprehensively assessed all relevant outcome domains of RA, including achievement of clinical response, clinical target states, functional improvement and inhibition of structural progression in patients with multiple PPFs at baseline. Such patients are generally expected to experience poor outcomes compared with patients without these risk factors, hence their designation as PPFs.2–5 In this study, treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX resulted in comparable efficacy relative to the overall population across clinical, functional and structural measures. The filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX regimen in particular had an incremental benefit versus MTX monotherapy in the multiple PPFs population; an added benefit of filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX and filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy versus MTX monotherapy was observed but inconsistent in this high-risk population. Patients with established RA (disease duration ≥6 months) may also benefit more from treatment with filgotinib 200 mg in combination with MTX relative to filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX, filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy or MTX alone.

Interpretation of subgroup analyses of patients with fewer than four PPFs was limited by small patient numbers and imbalances among treatment groups, as well as by better baseline status and/or slower progression in these patients relative to those with all four PPFs. Within these limitations, patients with all four PPFs were more likely to benefit from treatment with filgotinib (all doses) versus MTX monotherapy relative to patients with fewer than four PPFs. However, efficacy of filgotinib in combination with MTX versus MTX monotherapy was maintained in patients with only three or only two PPFs. Treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX appeared more effective versus filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy in patients with examined combinations of PPFs and particularly within subgroups of patients with CRP ≥4, possibly because filgotinib reduces CRP in a dose-dependent manner. It is possible that elevated serum CRP levels indicate greater inflammation and thus require a higher dose of filgotinib and/or combination therapy to suppress JAK-mediated inflammatory pathways. However, interpretation of this observation is limited by the relatively small numbers of patients with all four PPFs.

AEs in patients with four PPFs were generally comparable both to results in the overall population and between patients receiving treatment with all filgotinib regimens versus MTX monotherapy. The exceptions were infections, serious infections and herpes zoster infections, which were more frequent in patients with four PPFs receiving some filgotinib doses compared with either patients in the overall population receiving the same treatment or patients with PPFs receiving other treatments. The numbers of cases were too small to support any conclusions about safety in patients with PPFs relative to the overall population. In general, the safety profile of filgotinib relative to MTX in MTX-naive patients in FINCH 3 was maintained in this population and consistent with the integrated safety analysis.19 This is reassuring, as more AEs might be expected in this high disease activity subgroup relative to the overall study population.

This analysis was limited by its post hoc nature and the primary study design. The study was not powered for subgroup comparisons, and numbers of patients with four PPFs in each treatment arm were small. Relative importance of each of the four PPFs to patient outcomes was not assessed. Regression to the mean may have contributed to improvement in clinical outcomes due to the high baseline disease activity in patients with four PPFs, although no evidence of this was seen for radiographic outcomes. The EULAR guidelines note that bDMARDs and tsDMARDs are not recommended as first-line treatments because these do not clearly demonstrate superiority to MTX plus glucocorticoids.1 This could not be examined in the present study, which was not designed to compare treatment regimens with and without glucocorticoids. Of note, 45% of patients with four PPFs were receiving glucocorticoids, all dosed at ≤10 mg, at baseline (table 1). Glucocorticoid use did not appear to affect efficacy or safety of filgotinib in this population with the exception of greater numbers of infections in patients with versus without glucocorticoid use. However, interpretation is limited by the small numbers of patients and events in these post hoc ‘subgroup of subgroup’ analyses. Among patients with four PPFs, glucocorticoid use at baseline was associated with longer disease duration and more radiographic damage. These findings indirectly confirm current EULAR recommendations for glucocorticoid use in patients with RA as short-term ‘bridging’ therapy in conjunction with prompt initiation of DMARDs but not as monotherapy.1 EULAR also requested data on outcomes in patients both with and without PPFs,1 but the FINCH 3 trial population did not allow comparison of outcomes relative to patients without any PPFs because all patients had at least one PPFs per study inclusion criteria.

The results of the present study confirm that MTX-naive patients with RA with PPFs are at risk for treatment failure and radiographic progression following MTX monotherapy. These patients may thus warrant additional consideration of treatment escalation at the 3-month checkpoint. Treatment with filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX provided rapid and clinically meaningful improvement in disease control, including higher rates of remission, improved physical function and less radiographic progression, compared with MTX alone in MTX-naive patients with four PPFs. Treatment with filgotinib 100 mg plus MTX or filgotinib 200 mg monotherapy also showed some incremental benefit over MTX monotherapy in this population. The risk/benefit balance for filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX treatment appears reasonable in patients with RA with multiple PPFs, and filgotinib could be part of the treatment strategy for these patients. Given the efficacy of filgotinib 200 mg plus MTX in particular versus MTX monotherapy in this population, addition of filgotinib may be a reasonable option for patients with PPFs who have unsatisfactory response to MTX plus glucocorticoids or who relapse on glucocorticoid tapering.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their thanks to the study participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: DA, RW, CG-V, GA, AM, PB, ODM, MHB, BB, ZY, YG, TH and GRB contributed to manuscript development, reviewed each draft critically for intellectual content and approved the final version for submission. ZY and YG performed statistical analyses.

Funding: The study was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc. Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Judith M. Phillips, DVM, PhD, of Alpha Scientia, LLC, and funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Competing interests: DA reports grants or research support from AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Roche; serving as a consultant for Janssen; serving on a speaker’s bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme and UCB; and serving as a consultant and on a speaker’s bureau for AbbVie; Amgen; Celgene; Eli Lilly; Medac; Merck; Novartis; Pfizer; Roche; Sandoz; and Sanofi/Genzyme. RW reports grant/research support from and serving as a consultant for Celltrion; Galapagos; and Gilead Sciences, Inc. CG-V reports serving as a consultant and on a speaker’s bureau for AbbVie; Amgen; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Celgene; Eli Lilly; Galapagos; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Janssen; Medac; Merck-Serono; Mylan; Nordic Pharma; Novartis; Pfizer; Roche; Sandoz; Sanofi; and UCB. GA reports serving as a consultant for Amgen and Theramex. AM reports grants or research support from AbbVie; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Galapagos; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen; Novartis; Pfizer; Sanofi; UCB; and Regeneron; and serving as a consultant for AbbVie; Gilead Sciences, Inc; GlaxoSmithKline; and Novartis. PB reports serving as a consultant and on a speaker’s bureau for AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. ODM reports serving on a speaker’s bureau for Amgen, Pfizer and Americas Health Foundation. MHB reports grants or research support from Pfizer, Roche and UCB; and serving as a consultant for AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Gilead Sciences, Inc; Serono; Sandoz; and Sanofi. BB, ZY and YG are employees and shareholders of Gilead Sciences, Inc. TH is an employee and shareholder of Galapagos BV. GRB reports serving as a consultant and on a speaker’s bureau for AbbVie; Eli Lilly; Pfizer; and Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. The full data sharing policy for Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gilead.com/science-and-medicine/research/clinical-trials-transparency-and-data-sharing-policy.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:685–99. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vastesaeger N, Xu S, Aletaha D, et al. A pilot risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2009;48:1114–21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser K, Goekoop-Ruiterman YPM, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, et al. A matrix risk model for the prediction of rapid radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving different dynamic treatment strategies: post hoc analyses from the best study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1333–7. 10.1136/ard.2009.121160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DMFM, et al. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:823–7. 10.1136/ard.2008.090019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Van Der Heijde DMFM, St Clair EW, et al. Predictors of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate with or without concomitant infliximab: results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:702–10. 10.1002/art.21678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Rompaey L, Galien R, van der Aar EM, et al. Preclinical characterization of GLPG0634, a selective inhibitor of JAK1, for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J Immunol 2013;191:3568–77. 10.4049/jimmunol.1201348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genovese MC, Kalunian K, Gottenberg J-E, et al. Effect of filgotinib vs placebo on clinical response in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy: the finch 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;322:315–25. 10.1001/jama.2019.9055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanaugh A, Kremer J, Ponce L, et al. Filgotinib (GLPG0634/GS-6034), an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, is effective as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomised, dose-finding study (Darwin 2). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1009–19. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westhovens R, Taylor PC, Alten R, et al. Filgotinib (GLPG0634/GS-6034), an oral JAK1 selective inhibitor, is effective in combination with methotrexate (MTX) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and insufficient response to MTX: results from a randomised, dose-finding study (Darwin 1). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:998–1008. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combe B, Kivitz A, Tanaka Y, et al. Filgotinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate: a phase III randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:848–58. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westhovens R, Rigby WFC, van der Heijde D, et al. Filgotinib in combination with methotrexate or as monotherapy versus methotrexate monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and limited or no prior exposure to methotrexate: the phase 3, randomised controlled finch 3 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:727–38. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. 10.1002/art.1780380602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aletaha D, Smolen J. The simplified disease activity index (SDAI) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:S100–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League against rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:573–86. 10.1002/art.30129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prevoo ML, van 't Hof MA, Kuper HH, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:44–8. 10.1002/art.1780380107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137–45. 10.1002/art.1780230202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol 1982;9:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van Der Heijde method. J Rheumatol 2000;27:261–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genovese MC, Winthrop K, Tanaka Y. Integrated safety analysis of filgotinib treatment for rheumatoid arthritis from 7 clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:320. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2021-001621supp001.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised individual patient data will be shared upon request for research purposes dependent upon the nature of the request, the merit of the proposed research, the availability of the data, and its intended use. The full data sharing policy for Gilead Sciences, Inc., can be found at https://www.gilead.com/science-and-medicine/research/clinical-trials-transparency-and-data-sharing-policy.