Abstract

Objective

The addition of maintenance olaparib to bevacizumab demonstrated a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer in the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial (NCT02477644). We evaluated maintenance olaparib plus bevacizumab in the Japan subset of PAOLA-1.

Methods

PAOLA-1 was a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. Patients received maintenance olaparib tablets 300 mg twice daily or placebo twice daily for up to 24 months, plus bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks for up to 15 months in total. This prespecified subgroup analysis evaluated investigator-assessed PFS (primary endpoint).

Results

Of 24 randomized Japanese patients, 15 were assigned to olaparib and 9 to placebo. After a median follow-up for PFS of 27.7 months for olaparib plus bevacizumab and 24.0 months for placebo plus bevacizumab, median PFS was 27.4 versus 19.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio [HR]=0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.11–1.00). In patients with tumors positive for homologous recombination deficiency, the HR for PFS was 0.57 (95% CI=0.16–2.09). Adverse events in the Japan subset were generally consistent with those of the PAOLA-1 overall population and with the established safety and tolerability profiles of olaparib and bevacizumab.

Conclusion

Results in the Japan subset of PAOLA-1 support the overall conclusion of the PAOLA-1 trial demonstrating that the addition of maintenance olaparib to bevacizumab provides a PFS benefit in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02477644

Keywords: Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer, PAOLA-1, Olaparib, Bevacizumab, BRCA Mutation, Homologous Recombination Deficiency

INTRODUCTION

Ovarian cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed gynaecological cancer worldwide and the eighth most common cause of cancer death in women, with over 200,000 ovarian cancer-related deaths occurring in 2020 [1,2]. It is estimated that in Japan in 2020, there were nearly 11,000 new cases of ovarian cancer and over 5,000 ovarian-cancer-related deaths [3]. In 2014, 35% of Japanese patients with ovarian cancer had International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage III or IV disease at diagnosis [4].

The fact that patients with ovarian cancer are often diagnosed at a late stage means that the majority of the patients experience relapse despite undergoing cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy with curative intent [5,6].

First-line maintenance monotherapy with the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib provided a long-term progression-free survival (PFS) benefit for patients with advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation (BRCAm) in the phase III SOLO1 trial [7]. The phase III PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial investigated the addition of maintenance olaparib to the antiangiogenic agent bevacizumab in patients with advanced ovarian cancer who were in clinical response following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus bevacizumab and were unselected by biomarker or surgical status [8]. Maintenance olaparib plus bevacizumab provided a substantial PFS benefit versus bevacizumab alone in PAOLA-1 patients who tested positive for homologous recombination deficiency (HRD; defined as a presence of a BRCAm and/or genomic instability; genomic instability is defined as a genomic instability score of ≥42) (median 37.2 vs. 17.7 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.25–0.45). Based on this result, maintenance therapy with olaparib plus bevacizumab was approved in the USA, the EU, and Japan for HRD-positive patients with advanced ovarian cancer who are in response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus bevacizumab [9,10,11]. In addition, a significant PFS benefit was seen with olaparib plus bevacizumab versus bevacizumab alone in the overall PAOLA-1 population (HR=0.59; 95% CI=0.49–0.72; p<0.001) [8]. The results of PAOLA-1 highlight the importance of HRD testing to identify patients most likely to benefit from and eligible to receive olaparib plus bevacizumab as maintenance therapy.

This article reports results of a subgroup analysis of PAOLA-1 evaluating combination maintenance therapy with olaparib plus bevacizumab versus placebo plus bevacizumab in the Japan subset.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Trial design and patients

PAOLA-1 was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial conducted in 11 countries, including a subset of patients from 7 centers in Japan.

Patient eligibility criteria in PAOLA-1 have been described previously [8]. In brief, eligible patients were aged ≥18 years and had newly diagnosed, advanced (FIGO stage III or IV) high-grade serous or high-grade endometrioid ovarian, fallopian tube, and/or primary peritoneal cancer. Patients with other epithelial non-mucinous ovarian cancer were eligible if they had a germline BRCAm. Patients were eligible irrespective of surgical status (upfront or interval surgery, residual or no residual macroscopic disease) and had no evidence of disease or clinical complete or partial response after receiving first-line treatment with platinum–taxane chemotherapy plus bevacizumab. Patients received at least 3 cycles of bevacizumab with the last 3 cycles of chemotherapy, apart from those undergoing interval surgery, who were permitted to receive only 2 cycles of bevacizumab with the last 3 cycles of chemotherapy. A tumor sample had to be available for central BRCA testing and to determine HRD status. Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1. Full eligibility criteria are provided in the Data S1.

This trial was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines, under the auspices of an independent data monitoring committee. The trial was designed by the European Network of Gynaecological Oncological Trial Groups (ENGOT) lead group, Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO), and sponsored by Association de Recherche Cancers Gynecologiques (ARCAGY) Research, according to the ENGOT model A [12,13]. The PAOLA-1 protocol specified that approximately 24 Japanese patients would be recruited into the trial; Japanese patients were enrolled in Japan by the Gynecologic Oncology Trial and Investigation Consortium (GOTIC).

2. Randomization and treatment

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to olaparib tablets 300 mg twice daily or placebo twice daily using an interactive web or voice response system. Patients were randomized at least 3 weeks and no more than 9 weeks after the last dose of chemotherapy, and randomization was performed centrally using a block design with stratification according to the outcome of first-line treatment at screening and tumor BRCAm status (Data S1). Study treatment continued for up to 24 months from randomization or until disease progression in accordance with investigators' assessment of imaging (modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST], version 1.1 criteria) or unacceptable toxicity, whichever occurred first, as long as the patient experienced benefit and did not meet other discontinuation criteria. Crossover between treatment arms was not planned. After discontinuation of the intervention, patients could receive other treatments at the investigators' discretion. Patients were administered intravenous bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total duration of up to 15 months.

3. Endpoints and assessments

In PAOLA-1, the primary efficacy endpoint was the time from randomization until investigator-assessed disease progression (assessed by modified RECIST version 1.1) or death (ie PFS) [8]. Tumor assessment scans (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) were performed at baseline, then every 24 weeks (or at 12-week planned visits if there was evidence of clinical progression or progression based on serum CA-125 levels) up to month 42 or until the date of data cut-off (DCO).

This prespecified analysis evaluated investigator-assessed PFS in the Japan subset. The secondary endpoint of the time from randomization to second progression or death (PFS2) was also assessed in the Japan subset.

Safety and tolerability were evaluated as a secondary objective.

4. Statistical analysis

As previously reported [8], PAOLA-1 was designed to detect differences in investigator-assessed PFS in the overall population [8]. The PAOLA-1 Japan analysis was not powered to detect a statistically significant difference between treatment arms in investigator-assessed PFS. PFS was also assessed by blinded independent central review (BICR) in a sensitivity analysis and in the HRD-positive subgroup in an exploratory analysis.

Efficacy data were summarized and analyzed in the intent-to-treat population, which included all randomized patients, regardless of the intervention received. Safety data were summarized in the safety analysis set (all randomized patients who received at least one of dose of olaparib or placebo). PFS was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method; an unstratified log-rank test assessed the difference between the treatment groups. The PFS HR and 95% CI were calculated using a Cox proportional hazards model including a term for treatment. Adverse events (AEs) were analyzed descriptively.

RESULTS

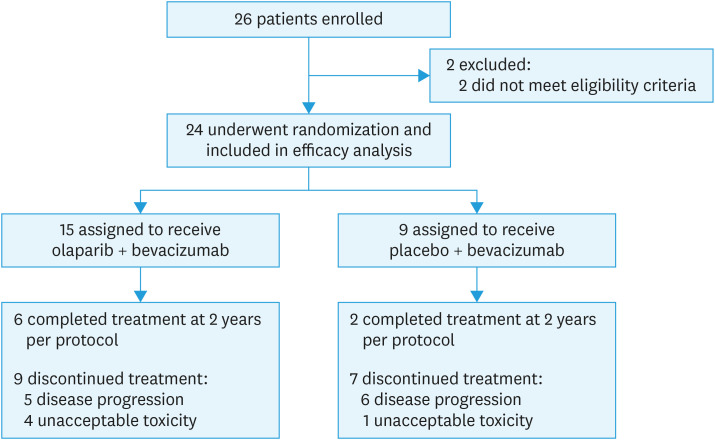

The PAOLA-1 trial randomized 806 patients globally from July 2015 through September 2017. Of the 24 patients randomized from 7 centers in Japan, 15 were assigned to olaparib plus bevacizumab and 9 to placebo plus bevacizumab (Fig. 1). The date of DCO for the primary PFS analysis was March 22, 2019.

Fig. 1. Patient disposition for the PAOLA-1 Japan subset.

Patient baseline characteristics in the Japan subset, including tumor BRCAm and HRD status, are shown in Table 1. Baseline characteristics were generally well balanced between treatment arms, although more patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group had macroscopic residual disease after undergoing upfront surgery than in the placebo plus bevacizumab group. Overall, a total of 21% and 67% of patients had a tumor BRCAm and were HRD positive, respectively. In addition, 21% of patients had a germline BRCAm in the overall Japan subset.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patients at baseline in the Japan subset*.

| Characteristics | Olaparib + bevacizumab (n=15) | Placebo + bevacizumab (n=9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, yr (range) | 61.0 (44–71) | 59.0 (44–70) | ||

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0 | 15 (100) | 8 (89) | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1 (11) | ||

| Primary tumor location | ||||

| Ovary | 8 (53) | 6 (67) | ||

| Fallopian tube | 2 (13) | 0 | ||

| Primary peritoneal | 5 (33) | 3 (33) | ||

| FIGO stage | ||||

| III | 10 (67) | 7 (78) | ||

| IV | 5 (33) | 2 (22) | ||

| Normal serum CA-125 level | ||||

| Yes | 13 (87) | 8 (89) | ||

| No | 2 (13) | 1 (11) | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Serous | 14 (93) | 9 (100) | ||

| Endometrioid | 1 (7) | 0 | ||

| History of cytoreductive surgery | ||||

| Upfront surgery | 8 (53) | 5 (56) | ||

| Macroscopic residual disease | 8 (100) | 3 (60) | ||

| Complete resection | 0 | 2 (40) | ||

| Interval surgery | 7 (47) | 4 (44) | ||

| Macroscopic residual disease | 1 (14) | 0 | ||

| Complete resection | 6 (86) | 4 (100) | ||

| No surgery | 0 | 0 | ||

| Response after first-line chemotherapy | ||||

| No evidence of disease† | 5 (33) | 5 (33) | ||

| Complete response‡ | 6 (40) | 4 (44) | ||

| Partial response§ | 4 (27) | 2 (22) | ||

| Deleterious tumor BRCAm | ||||

| Yes | 3 (20) | 2 (22) | ||

| No | 12 (80) | 7 (78) | ||

| Myriad tumor HRD status∥ | ||||

| HRD positive | 10 (67) | 6 (67) | ||

| HRD negative | 3 (20) | 3 (33) | ||

| HRD test cancelled/failed | 2 (13) | 0 | ||

Values are presented as number (%).

BRCAm, BRCA mutation; CA-125, cancer antigen; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HRD, homologous recombination repair deficiency; ULN, upper limit of normal.

*Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding. †No evidence of disease was defined as no measurable/assessable disease after cytoreductive surgery plus no radiologic evidence of disease and a normal CA-125 level after chemotherapy. ‡Complete response was defined as disappearance of all measurable/assessable disease and normalization of CA-125 levels. §Partial response was defined as radiologic evidence of disease and/or an abnormal CA-125 level. ∥HRD positive was defined as tumor BRCAm and/or genomic instability score of ≥42 with the myChoice® CDx assay (Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, USA). HRD negative was defined as genomic instability score of <42.

At the primary PFS analysis DCO, median follow-up for PFS in the Japan subset was 27.7 (interquartile range [IQR], 24.8–29.1) months and 24.0 (IQR, 24.0–24.0) months in the olaparib plus bevacizumab and placebo plus bevacizumab groups, respectively. At the time of DCO, PFS events had occurred in 16 of 24 patients (67% data maturity). The number of PFS events in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group was 8 (53%) and in the placebo plus bevacizumab group was 8 (89%).

The duration of investigator-assessed PFS was significantly longer in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group than in the placebo plus bevacizumab group (median 27.4 vs.19.4 months; HR=0.34; 95% CI=0.11–1.00; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier estimate of investigator assessed progression-free survival in the Japan subset.

Results of the sensitivity analysis of PFS by BICR were consistent with those of the investigator-based PFS analysis, with a median PFS of 27.2 months in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group versus 18.3 months in the placebo plus bevacizumab group (HR=0.40; 95% CI=0.13–1.23). In patients with tumors positive for HRD, the HR for PFS with olaparib plus bevacizumab versus placebo plus bevacizumab was 0.57 (95% CI=0.16–2.09).

In the analysis of PFS2 (54% data maturity), median PFS2 was 28.7 months in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group and 28.6 months in the placebo plus bevacizumab group (HR=0.88; 95% CI=0.28–3.02).

Median duration of treatment was 16.8 (range, 2.0–24.0) months for olaparib and 19.5 (range, 1.2–24.0) months for placebo. Median duration of treatment with bevacizumab since randomization was 11.2 (range, 2.5–14.7) and 11.0 (range, 1.4–14.0) months in the olaparib plus bevacizumab and placebo plus bevacizumab groups, respectively.

The most common AEs and the associated grade ≥3 AEs reported in the Japan subset are shown in Table 2. The most commonly reported AEs (all grades) that occurred with a numerically higher incidence among patients receiving olaparib plus bevacizumab than among those receiving placebo plus bevacizumab were anemia, neutropenia, and leukopenia. The most commonly reported AEs (all grades) that occurred with a numerically higher incidence among patients receiving placebo plus bevacizumab than among those receiving olaparib plus bevacizumab were hypertension and proteinuria.

Table 2. Summary of AEs in the Japan subset*.

| AE | Olaparib + bevacizumab (n=15) | Placebo + bevacizumab (n=9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade ≥3 | All grades | Grade ≥3 | |

| Anemia† | 11 (73) | 5 (33) | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Leukopenia‡ | 11 (73) | 4 (27) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) |

| Neutropenia§ | 11 (73) | 3 (20) | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia¶ | 8 (53) | 2 (13) | 4 (44) | 2 (22) |

| Nausea | 6 (40) | 0 | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 4 (27) | 0 | 8 (89) | 2 (22) |

| Increased weight | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (44) | 1 (11) |

| Thrombocytopenia¶ | 2 (13) | 0 | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 2 (13) | 0 | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Gingivitis | 2 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypersensitivity | 2 (13) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 1 (7) | 0 | 4 (44) | 0 |

| Pelvic infection | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (22) | 1 (11) |

| URTI | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (22) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (22) | 0 |

| Constipation | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (22) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 3 (33) | 1 (11) |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (22) | 0 |

Values are presented as number (%).

AE, adverse event; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

*Data are shown for all-grade AEs that occurred in at least 10% of patients in either treatment group and the associated incidence of grade ≥3 AEs during study treatment or up to 30 days after discontinuation of the intervention. AEs were graded using National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03). †Anemia includes anemia, decreased hemoglobin level, decreased hematocrit, decreased red blood cell count, erythropenia, macrocytic anemia, normochromic anemia, normochromic normocytic anemia, and normocytic anemia. ‡Leukopenia includes leukopenia and decreased white blood cell count. §Neutropenia includes neutropenia, febrile neutropenia, neutropenic sepsis, neutropenic infection, decreased neutrophil count, idiopathic neutropenia, granulocytopenia, decreased granulocyte count, and agranulocytosis. ∥Lymphopenia includes decreased lymphocyte count, lymphopenia, decreased B-lymphocyte count, and decreased T-lymphocyte count. ¶Thrombocytopenia includes thrombocytopenia, decreased platelet production, decreased platelet count, and decreased plateletcrit.

Serious AEs occurred in 27% and 22% of patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab and placebo plus bevacizumab groups, respectively (Table S1). The most commonly reported serious AE was anemia (20% of olaparib plus bevacizumab patients vs. 0% of placebo plus bevacizumab patients). No fatal AEs were reported in either treatment arm.

In terms of AEs of special interest to olaparib, no cases of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), new primary malignancies, or pneumonitis were reported in either treatment group in the Japan subset.

In the majority of cases, AEs were managed with dose modification. Dose interruption because of AEs occurred in 73% of patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group and 44% of patients in the placebo plus bevacizumab group, with dose reduction because of AEs occurring in 60% and 0% of patients, respectively. Discontinuation because of AEs occurred in 27% of patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group and 11% of patients in the placebo plus bevacizumab group (Table S2).

DISCUSSION

The PFS benefit seen in the Japan subset of the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial was generally consistent with that reported in the overall PAOLA-1 population. In the Japan subset, the addition of maintenance olaparib, compared with placebo, to bevacizumab reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 66% (HR=0.34; 95% CI=0.11–1.00) in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer. This compares with the 41% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death seen in the overall PAOLA-1 population (HR=0.59; 95% CI=0.49–0.72) [8].

The PFS benefit seen with olaparib plus bevacizumab versus placebo plus bevacizumab in the Japan subset was supported by the results of a sensitivity analysis evaluating PFS by BICR (HR=0.40; 95% CI=0.13–1.23).

In terms of biomarker status, the proportion of patients with a tumor BRCAm in the Japan subset (21%) was similar to that in the overall PAOLA-1 population (30%) [8]. A germline BRCAm was reported in 21% of patients in the Japan subset. A nationwide study of 634 Japanese women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer found an overall germline BRCAm prevalence of 15%, with a higher prevalence of germline BRCA1 mutations (10%) than germline BRCA2 mutations (5%) [14]. In PAOLA-1, there were slightly more HRD-positive patients in the Japan subset (67%) than in the overall population (48%) [8], although this needs to be confirmed in a larger study. Ongoing studies are further evaluating the prevalence of BRCA mutations and HRD positivity in Japanese patients with ovarian cancer (CHRISTELLE; UMIN000039226; NCT04222465).

Maintenance therapy with olaparib plus bevacizumab was associated with a substantial PFS benefit compared with bevacizumab alone in HRD-positive patients in the overall PAOLA-1 population (HR=0.33; 95% CI=0.25–0.45) [8]. The small number of patients in the Japan subset who were HRD positive (n=16) makes interpretation of these data difficult; the HR for PFS in the HRD-positive subgroup was 0.57 (95% CI=0.16–2.09).

The PFS2 results in the Japan subset were consistent with those reported in an interim analysis of PFS2 in the overall PAOLA-1 population (HR=0.86; 95% CI=0.69–1.09) (DCO March 22, 2019) [8]. Owing to the small number of patients in the Japan subset, overall survival was not evaluable.

The safety profile of olaparib plus bevacizumab in the Japan subset was generally consistent with that of the overall PAOLA-1 population [8] and with the established safety and tolerability profiles of olaparib and bevacizumab. There appeared to be a lower incidence of hypertension (a toxicity frequently seen with bevacizumab) in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group in the Japan subset (27%) than in the overall PAOLA-1 population (46%) [8], although patient numbers in the Japan subset are small. No cases of fatigue or asthenia were reported in the Japan subset, whereas fatigue/asthenia was reported in 53% of patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group in the overall PAOLA-1 population [8]. The incidence of grade ≥3 AEs was generally higher in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group in the Japan subset (73%) than in the overall PAOLA1 population (57%), although these data should be interpreted in the context of the small number of patients in the Japan subset.

In terms of AEs of interest for olaparib, no cases of MDS, AML, or new primary malignancies were reported in the Japan subset at the time of DCO (March 22, 2019). In the overall PAOLA-1 population [8], MDS, AML, or aplastic anemia was reported in 6 of 535 (1%) patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group and 1 of 267 (<1%) patients in the placebo plus bevacizumab group in the primary analysis [8]. MDS/AML has also been reported in trials of PARP inhibitor maintenance monotherapy in the settings of newly diagnosed [15,16] and relapsed ovarian cancer [17,18,19,20]. Results of a recent meta-analysis in patients with various cancers suggest that PARP inhibitors (maintenance therapy or treatment) increased the risk of MDS and AML compared with placebo [21].

The main limitation of this analysis is the small sample size, which makes it difficult to interpret data in subgroups, such as patients who tested positive for HRD. A slight imbalance in prognostic factors between treatment groups, with more patients in the olaparib plus bevacizumab group compared with the placebo plus bevacizumab group having macroscopic residual disease after upfront surgery, may have also impacted results.

In conclusion, this analysis of the Japan subset of PAOLA-1 supports the overall conclusion of the PAOLA-1 trial that the addition of maintenance olaparib to bevacizumab provides a PFS benefit in patients with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The PAOLA-1 trial was conducted as an investigator-initiated registration trial in Japan with support from the Global Health Research Coordinating Center (GHRCC) of Kanagawa Institute of Science and Technology (KISTEC), the Gynecologic Oncology Trial and Investigation Consortium (GOTIC) study coordinating center, and GOTIC administration office. Writing assistance was provided by Esmie Wescott, PhD from Mudskipper Business Ltd, funded by AstraZeneca and MSD.

Footnotes

Synopsis: The Japan subset of the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-ov25 trial included 24 women with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer. A progression-free survival benefit was seen with the addition of olaparib versus placebo to bevacizumab maintenance therapy (hazard ratio=0.34; 95% confidence interval=0.11–1.00). Safety results were consistent with the overall PAOLA-1 population.

Presentation: The data have been presented at the ESMO Asia Virtual Congress 2020, held on 20–22 November 2020.

Funding: This study was funded by ARCAGY Research, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD), and F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Conflict of Interest: Professor Keiichi Fujiwara reports receiving consulting fees and grant support from Pfizer, Eisai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Taiho, Zeria, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Genmab, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, receiving grant support from Immunogen, Oncotherapy, and Regeneron, and receiving consulting fees from Novartis, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Daiichi Sankyo, Mochida Pharmaceutical, and NanoCarrier; Dr Toyomi Satoh reports receiving consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo, Kyowa Kirin, Eisai, Tsumura, Nippon Kayaku, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Bayer Yakuhin, ASKA Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Nobelpharma, and Ono Pharmaceutical; Dr Kan Yonemori reports receiving lecture fees and advisory fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company and Esai, receiving lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Daiichi Sankyo, and advisory fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Novartis; Dr Shogi Nagao reports receiving consulting fees and grant support from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, consulting fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Asahi Kasei Medical, and Mochida Pharmaceutical, and grant support from AbbVie, Clovis Oncology, Pfizer, Toray, Tosoh, and Preferred Networks; Dr Philipp Harter reports receiving consulting fees and grant support AstraZeneca, Roche, Tesaro, and GlaxoSmithKline, consulting fees from Sotio, Zai Lab, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Clovis Oncology, and Immunogen, and grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Medac, Genmab, the European Union, Deutsche Krebshilfe, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; Dr Isabel Palacio Vazquez reports receiving payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, travel fees from Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Roche, and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol, GSK, and Clovis Oncology; Tomoko Fujita reports being employed by AstraZeneca and being a shareholder of AstraZeneca; Philip Rowe reports being employed by AstraZeneca; Professor Eric Pujade-Lauraine reports receiving consulting and other non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Roche, and Tesaro, consulting fees from Clovis Oncology, Incyte, and Pfizer, and holds the role as chairperson in ARCAGY Research; Professor Isabelle Ray-Coquard reports receiving consulting fees, grant and travel support from AstraZeneca and Roche, consulting fees and travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, consulting fees from Clovis Oncology, PharmaMar, Mersana Therapeutics, Deciphera Pharmaceutical, Amgen, and Chugai Pharmaceutical, grant support from Bristol Myers Squibb, and consulting fees and grant support from Merck Sharp & Dohme; Dr Hiroyuki Fujiwara, Dr Hiroyuki Yoshida, Dr Takashi Matsumoto, Dr Hiroaki Kobayashi, Dr Hugues Bourgeois, Dr Anna Maria Mosconi, and Dr Alexander Reinthaller report no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

Data Sharing Statement: ARCAGY-GINECO has a long history of academic data sharing for research purposes. The process is similar for every trial sponsored by ARCAGY-GINECO (or ARCAGY Research):

• Researchers have to submit a request to the sponsor directly or through the principal investigator. The request should be written in a predefined format of a short synopsis indicating the objective of the research, the methodology intended to be used, including the statistical analysis plan, and the variables within the database required for the research.

• A scientific board will review and approve the requests on a case-by-case basis.

Only encoded datasets will be used, which enables us to fulfill legal and ethical obligations to protect our patients while at the same time utilizing patient data in progressing medical research to its full potential in the best interests of public health.

A specific agreement between the sponsor and the researcher is requested for data transfer. This data transfer agreement details both parties' responsibilities to ensure the required level of data integrity and legal and ethical obligations.

In the case of sharing encoded patient-level data, please note that the full dataset may not be shared in view of the following:

• Clinical consent for some countries prohibits secondary use of the data.

• Patients may withdraw their consent for participation in the trial at any point.

• Other aspects might also be taken into consideration to protect patient privacy (e.g., review of rare clinical events where information is aggregated to a higher level before sharing).

- Conceptualization: E.P.L., I.R.C.

- Formal analysis: T.F., P.R.

- Investigation: K.F., H.F., H.Y., T.S., K.Y., S.N., T.M., H.K., H.B., P.H., A.M.M., I.P.V., A.R., E.P.L., I.R.C.

- Methodology: E.P.L., I.R.C.

- Writing - original draft: K.F., H.F., H.Y., T.S., K.Y., S.N., T.M., H.K., H.B., P.H., A.M.M., I.P.V., A.R., T.F., P.R., E.P.L., I.R.C.

- Writing - review & editing: K.F., H.F., H.Y., T.S., K.Y., S.N., T.M., H.K., H.B., P.H., A.M.M., I.P.V., A.R., T.F., P.R., E.P.L., I.R.C.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

PAOLA-1 study design

Serious adverse events

Discontinuations due to adverse events

References

- 1.The International Association of Cancer Registries (IACR) The Global Cancer Observatory cancer fact sheets: ovary [Internet] 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 4]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/25-Ovary-fact-sheet.pdf.

- 2.The International Association of Cancer Registries (IACR) The Global Cancer Observatory mortality rates in women [Internet] 2020. [cited 2021 Feb 18]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-pie?v=2020&mode=cancer&mode_population=continents&population=900&populations=900&key=total&sex=2&cancer=39&type=1&statistic=5&prevalence=0&population_group=0&ages_group%5B%5D=0&ages_group%5B%5D=17&nb_items=15&group_cancer=1&include_nmsc=1&include_nmsc_other=1&half_pie=0&donut=1.

- 3.The International Association of Cancer Registries (IACR) The Global Cancer Observatory in Japan [Internet] 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 4]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/392-japan-fact-sheets.pdf.

- 4.Yamagami W, Nagase S, Takahashi F, Ino K, Hachisuga T, Aoki D, et al. Clinical statistics of gynecologic cancers in Japan. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28:e32. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doubeni CA, Doubeni AR, Myers AE. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:937–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, Gonzalez-Martin A, Colombo N, Sessa C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(Suppl 6):vi24–vi32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, et al. 811MO Maintenance olaparib for patients (pts) with newly diagnosed, advanced ovarian cancer (OC) and a BRCA mutation (BRCAm): 5-year (y) follow-up (f/u) from SOLO1. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(Suppl 4):S613. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, Pérol D, González-Martín A, Berger R, et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2416–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AstraZeneca. LYNPARZA® (olaparib) tablets, for oral use: prescribing information [Internet] 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/208558s014lbl.pdf.

- 10.AstraZeneca. Lynparza summary of product characteristics [Internet] 2020. [cited 2020 Nov 24]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lynparza-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- 11.AstraZeneca. Lynparza approved in Japan for the treatment of advanced ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancers [Internet] 2020. [cited 2021 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/content/astraz/media-centre/press-releases/2020/lynparza-approved-in-japan-for-three-cancers.html.

- 12.Vergote I, Pujade-Lauraine E, Pignata S, Kristensen GB, Ledermann J, Casado A, et al. European Network of Gynaecological Oncological Trial Groups' requirements for trials between academic groups and pharmaceutical companies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:476–478. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d3caa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Pignata S, Ledermann J, Casado A, et al. European Network of Gynaecological Oncological Trial Groups' requirements for trials between academic groups and industry partners – first update 2015. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1328–1330. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enomoto T, Aoki D, Hattori K, Jinushi M, Kigawa J, Takeshima N, et al. The first Japanese nationwide multicenter study of BRCA mutation testing in ovarian cancer: CHARacterizing the cross-sectionaL approach to Ovarian cancer geneTic TEsting of BRCA (CHARLOTTE) Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29:1043–1049. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2391–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledermann JA, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, et al. Overall survival in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent serous ovarian cancer receiving olaparib maintenance monotherapy: an updated analysis from a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30376-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, Oza AM, Mahner S, Redondo A, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D, Aghajanian C, Oaknin A, Dean A, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morice PM, Leary A, Dolladille C, Chrétien B, Poulain L, González-Martín A, et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukaemia in patients treated with PARP inhibitors: a safety meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and a retrospective study of the WHO pharmacovigilance database. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e122–34. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PAOLA-1 study design

Serious adverse events

Discontinuations due to adverse events