Abstract

Objective:

Increasing evidence points to mild alterations in everyday functioning early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), despite prior research suggesting functional declines occur primarily in later stages. However, daily function assessment is typically accomplished with subjective self- or informant-report, which can be prone to error due to various factors. Performance-based functional assessments (PBFAs) allow for objective evaluation of daily function abilities, but little is known on their sensitivity to the earliest ADRD-related brain alterations. We aimed to determine the neural correlates of three different PBFAs in a pilot study.

Method:

A total of 40 older participants (age=70.9±6.5 years; education=17.0±2.6 years; 51.5% female; 10.0% non-White; 67.5% cognitively normal) completed standardized PBFAs related to medication management (MM), finances (FIN), and communication abilities (COM). Participants underwent diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) scans, from which mean fractional anisotropy (FA) composite scores of late- (LMF) and early-myelinated (EMF) fibers were calculated. Linear regression analyses controlling for age and global cognition were used to assess the relationship of PBFAs with FA.

Results:

Better performance on MM was associated with higher mean FA on LMF composite (t38=2.231, p=0.032), while FIN and COM were not (ps>0.05). PBFAs were not associated with EMF (p>0.05).

Conclusions:

Our preliminary findings demonstrate better performance on a PBFA of medication management is associated with higher FA in late-myelinated white matter tracts. Despite a small sample size, these results are consistent with growing evidence that performance-based functional assessments may be a useful tool in identifying early changes related to ADRD.

Keywords: aging, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, cognition, activities of daily living

Introduction

Pathological changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative dementias have been well documented to begin years prior to clinical manifestation (Jack et al., 2018), raising important questions as to how to best detect the earliest cognitive and functional changes in aging adults. Moreover, as noted by the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease (NAPA, 2018), there is a clear need to identify these early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) using cost-effective methods that can be implemented across diverse communities. Objective assessment of cognitively demanding activities of daily living, which could be more adaptable and broadly disseminated than traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological testing, may offer such a method for earlier detection of cognitive decline in ADRD.

Recent studies of everyday function associated with healthy aging and neurodegenerative disease have challenged the notion that people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) maintain a level of intact daily function (Seligman & Giovannetti, 2015). While loss of functional independence is the primary diagnostic distinction between MCI and dementia, there is increasing evidence that impairments in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as managing medications and finances, occur early in the continuum of cognitive impairment. In one study using a functional self-report questionnaire, difficulties with household and financial management were particularly predictive of progression from normal cognition to MCI and were useful in discriminating between the two groups (Marshall et al., 2015). These early functional impairments may have previously gone undetected due to inherent limitations of self- and informant-report functional measures, such as lack of insight, mood, or caregiver distress (Shulman et al., 2006). Utilization of objective performance-based functional assessments (PBFAs) may provide additional insight into early functional changes that may be otherwise missed. For example, by employing a PBFA, Giovannetti and colleagues found evidence for clear functional deficits in individuals with MCI compared to cognitively normal individuals (Giovannetti et al., 2008). Individuals with MCI and subtle IADL deficits may also be more likely to progress to a dementia syndrome than those without IADL deficits (Teng et al., 2010). These findings make intuitive sense, as MCI has been conceptualized as an intermediary severity between healthy aging and a dementia diagnosis (Petersen et al., 1999; Reisberg et al., 2008), suggesting that functional changes likely occur on a measurable continuum.

While objective assessment for subtle IADL deficits using PBFAs may offer a novel method of earlier detection of cognitive decline, avoiding potential biases of self- and informant-report, there is limited evidence for the connections between functional measures and underlying neurodegenerative pathophysiology (Jekel et al., 2015). Furthermore, previous studies are limited by the use of self- or informant-report functional measures in their comparisons to neuroimaging biomarkers of ADRD (Vemuri et al., 2009). While objective measures of cognitive functional abilities may be a superior tool for assessing the earliest functional changes in MCI and dementia, little is known regarding the relationship between PBFAs and neuroimaging biomarkers associated with pathological aging and neurodegenerative disease. Better characterization of these relationships would support the wider use of PBFAs and allow for integration of earlier functional impairments into the accepted continuum of cognitive decline in ADRD.

Although dementias are often considered diseases of grey matter, alterations in white matter integrity are a common finding and very early marker of ADRD. In a recent study of AD mutation carriers, evidence of white matter disease was noted up to 22 years prior to manifestation of symptoms, suggesting that white matter alterations not only play a critical role in the pathogenesis of ADRD but moreover may presage clinical presentation (Lee et al., 2018; Nasrabady et al., 2018). According to the white matter retrogenesis hypothesis, late-myelinated fiber tracts are the earliest and most affected in ADRD via pathways related to increased susceptibility to amyloid deposition (Bartzokis, 2004; Bartzokis et al., 2007; Brickman et al., 2012). Indeed, diffusion tensor imaging studies in individuals with ADRD have shown lower fractional anisotropy in late-myelinated fibers (LMF) compared to early-myelinated fibers (EMF) (Stricker et al., 2009). Summary measures of these fibers have been developed and validated in aging and an association between LMF and cognitive decline has been reported (Brickman et al., 2012). In the current study, we examined the relationship between PBFAs and these measures of white matter integrity, differentiating EMF and LMF, in an aging and MCI population. We hypothesized that worse PBFA scores would be associated with lower integrity (as measured by fractional anisotropy [FA]) of LMF but not EMF. Given noted limitations of questionnaire-based assessment of daily function, we also hypothesized that there would be no significant association between these measures and EMF or LMF. As a secondary aim of the current study, we examined the possible mediating role of cognitive function on the relationship between PBFAs and white matter integrity. Given the strong relationship between PBFAs and traditionally-defined cognitive domains, we expected that the relationship between LMF and PBFA would be mediated by performance on traditional cognitive tests. Lastly, as an exploratory aim, we examined differences in this relationship between those with normal cognition and those with MCI.

Methods

Participants

A total of 40 individuals (age=70.9±6.5 years; education=17.0±2.6 years; 51.5% female; 10.0% non-White; 67.5% cognitively normal) were recruited from a larger cohort study on aging and ADRD through the University of Colorado Alzheimer’s and Cognition Center. This larger longitudinal study, the Bio-AD Study, entails comprehensive cognitive testing, health history assessment, neurological and physical examination, informant interview, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of all participants. In order to characterize the very earliest functional changes within the spectrum of cognitive decline, only clinically healthy older adults and adults with MCI were approached to participate in the current study. Inclusion as a “clinically healthy” participant was determined by a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Morris, 1997) score of 0, no informant report of significant cognitive decline during the previous year, and consensus conference adjudication as a normal control. Inclusion as a participant with mild cognitive impairment was based on 2011 NIA-AA core clinical criteria (Sperling et al., 2011). Participants were excluded if they had a major psychiatric disorder, current neurological condition known to affect cognition (e.g., Parkinson’s disease; large vessel infarct; multiple sclerosis), current evidence or history in the past 2 years of a focal brain lesion, current substance abuse, significant systemic medical illness or active neoplastic disease (e.g., current cancer), significant sensory or motor deficits that would interfere with cognitive testing, or traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness greater than 5 minutes. All participants were reviewed at a case conference with a board-certified neuropsychologist [BB], neurologist, and clinical research coordinator. A subset of cognitive measures from the research protocol was reviewed in a consensus conference and used in the adjudication of diagnosis as a clinically normal older adult or adult with MCI; however, to reduce circularity in our methodological approach, cognitive measures that were reviewed in the consensus conference for adjudication of diagnosis were separate from those used as primary outcomes in our research study.

Sample demographics of individuals who completed the pilot study are provided below in Table 1. All participants signed informed consent approved by the University of Colorado Institutional Review Board. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Colorado (Harris et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|

|

||

| Age | 70.85 (6.49) | 55–81 |

| Education | 16.95 (2.56) | 12–21 |

| N | % | |

| Handedness – Right | 38 | 95.0 |

| Gender—Female | 21 | 52.5 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 36 | 90.0 |

| Black/African American | 2 | 5.0 |

| 2+ Races/Unknown | 2 | 5.0 |

| Hispanic (all races) | 4 | 10.0 |

| Primary Language | ||

| English | 37 | 92.5 |

| Spanish | 1 | 2.5 |

| Other | 2 | 5.0 |

Procedures

Participants completed cognitive testing with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005), the Spanish English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales [SENAS (Mungas et al., 2005)], a battery of self-reported [Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale, or IADLS (Lawton & Brody, 1969)], informant-reported [Functional Activities Questionnaire, or FAQ (Pfeffer et al., 1982)], and performance-based [UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment, or UPSA (Patterson, Goldman, McKibbin, Hughs, & Jeste, 2001); Medication Management Ability Assessment, or MMAA (Patterson et al., 2002)] measures of daily function, and neuroimaging with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).

Cognition.

The SENAS battery was based on item response theory (IRT), and psychometrically matched measures were created across different scales, thus assuring reliability across the full ability continuum (Mungas, Reed, Crane, Haan, & Gonzalez, 2004; Mungas, Reed, Haan, & Gonzalez, 2005; Mungas, Reed, Marshall, & Gonzalez, 2000; Mungas, Reed, Tomaszewski Farias, & DeCarli, 2005; Mungas, Widaman, Reed, & Tomaszewski Farias, 2011). For data reduction purposes, we examined the Executive and Semantic abilities composites as well as the Verbal Memory composites. SENAS composite scores are unadjusted standard scores based on a diverse, older adult sample (≥60 years of age) and are not corrected for age or other demographics (Mungas et al., 2005). These composites were chosen due to extant research that suggests PBFAs are largely associated with aspects of these cognitive abilities (Goldberg et al., 2010).

Function.

The UPSA is a standardized battery comprised of cognitively demanding real-world daily activities, completed by the respondent through role-playing and scored by a trained examiner. Five domains are measured – (1) Finances; (2) Communication; (3) Planning/Organization; (4) Travel; and (5) Household Chores. The tasks employ a standardized set of props (i.e., U.S. currency, utility bill, telephone, bus map and schedule, and pantry stocked with nonperishable goods). Examples of tasks assessed include making change and calling the doctor’s office to reschedule an appointment. Index scores for each domain range from 0–20. The UPSA has been previously validated in MCI and ADRD (Goldberg et al., 2010). Additional validation studies have supported use of a brief version of the UPSA, comprised of the Finances and Communication sub-sections (Mausbach et al., 2007) and can be administered in 10–15 minutes; index scores for Finances and Communication were used in the current study.

The MMAA, similar to the UPSA, is a cognitively demanding, standardized PBFA that uses roleplaying to assess the respondent’s ability to develop and carry out a hypothetical medication regimen. Respondents are given standardized props in the form of four pill bottles with specific instructions on dosing and when the medications should be taken (e.g., before bed, with/without food). The respondent is then asked to describe and carry out a plan to take the medications by walking the examiner through a given day. Administration time is about 10 minutes and scores for the MMAA range from 0–33 possible points. Evidence suggests the MMAA is sensitive to functional changes in MCI (Sumida et al., 2018).

Neuroimaging.

Whole brain MRI scans were obtained on a 3.0 Tesla Siemens (Iselin, NJ) Skyra scanner equipped with a 20-channel head coil. Diffusion imaging data were acquired via a spin-echo, echo planar imaging sequence with 56 slices 2.2 mm thick (TR/TE = 8400/105 ms, matrix = 112×112) in monopolar series (multi-shell; B2500: 64 diffusion directions, B0 [9 averages]). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data were preprocessed and analyzed using FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox (FDT) (Smith et al., 2006). Raw data were corrected for head movement and eddy current distortions using FDT. Brain extraction and binary brain mask creation used the b0 mean image through the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) Brain Extraction Tool (BET). Fractional anisotropy (FA) maps were created using FSL DTIFIT. All subjects’ FA data were registered using the nonlinear registration FNIRT to the IXI Aging DTI Template (Zhang, Yushkevich, Rueckert, & Gee) masked by a study-specific average image. The mean FA and mean FA skeleton were created from the study sample. For region of interest (ROI) analyses, we employed the Johns Hopkins University ICBM-DTI-81 white matter labels (Mori et al., 2008) to label and mask areas of the white matter skeleton. Mean FA values for each white matter region was calculated using the FSL utility fslstats. Composite FA scores were calculated consistent with prior studies (Brickman et al., 2012). In order to calculate the early-myelinated fibers (EMF), we obtained the mean FA of the following regions: inferior cerebellar peduncles, superior cerebellar peduncle, anterior limb of the internal capsule, retrolenticular part of the internal capsule, and superior fronto-occipital fasciculus. For late-myelinated fibers (LMF), we used: genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum, fornix, and uncinate fasciculus. The composite EMF and LMF scores were calculated as the overall mean fractional anisotropy (FA) values of all the tracts included after averaging left and right hemispheres (where applicable).

Analysis

Data were checked for normality and outliers. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the relationship of ROIs and PBFAs; analyses controlled for age and global cognition [as measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or MoCA (Nasreddine et al., 2005)] in order to test if PBFAs explained meaningful variance in brain structure above and beyond a proxy of global cognitive function. In order to examine the possible mediating role of cognition on the relationship between ROIs and PBFAs, the PROCESS macro v. 3.3 (Hayes, 2018) for SPSS was used with 5000 bootstraps. Simple mediation models, which rely on causal inference, tested direct and indirect paths between ROIs as predictors, PBFAs as outcomes, and performance on traditionally-defined cognitive domains as mediators. All analyses were done using SPSS v. 25 (IBM Corp., 2017).

Results

Clinical characteristics for the entire sample as well as by clinical subgroup are described in Table 2. Pearson correlations revealed that age, education, and gender were not correlated with any of the three PBFAs (all ps>0.05). Global cognition as measured by the MoCA was significantly correlated with all three PBFAs (Finances: r=0.435, p=0.006; Communication: r=0.538, p<0.001; Medication Management: r=0.494; p=0.001). Age was significantly correlated with both EMF (r=−0.481, p=0.002) and LMF (r=−0.584, p<0.001), but the MoCA was not (both ps>0.05). Separate linear regression analyses with EMF or LMF as dependent variables and age, education, and gender as independent variables revealed age was the sole predictor of both summary scores (EMF: β= −0.00164, 95% CI [−0.00252, −0.00076], p=0.001; LMF: β= −0.00247, 95% CI [−0.00362, −0.00132], p<0.001).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Sample

|

Full Sample

|

CDR=0

|

CDR>0

|

p | ||||

| CDR | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

|

|

|||||||

| 0 | 27 | 67.5 | 27 | 67.5 | |||

| 0.5 | 12 | 30.0 | 12 | 30.0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.5 | |||

| Cognitive | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|

|

|||||||

| MoCA | 25.20 (2.93) | 20 to 30 | 26.22 (2.67) | 21 to 30 | 23.08 (2.29) | 20 to 28 | 0.001 |

| Executive | 0.36 (0.55) | −0.78 to 1.72 | 0.54 (0.52) | −0.56 to 1.72 | 0.00 (0.45) | −0.78 to 1.10 | 0.003 |

| Semantic | 1.45 (0.69) | −0.38 to 2.69 | 1.68 (0.60) | 0.37 to 2.69 | 0.96 (0.63) | −0.38 to 2.01 | 0.001 |

| Verbal Memory | 0.68 (0.85) | −0.97 to 2.64 | 0.99 (0.69) | −0.78 to 2.64 | 0.03 (0.81) | −0.97 to 1.28 | <0.001 |

| Function | |||||||

| Communication | 14.53 (3.45) | 2 to 20 | 15.67 (2.53) | 10 to 20 | 12.15 (3.98) | 2 to 17 | 0.002 |

| Finances | 17.90 (2.05) | 13 to 20 | 18.33 (1.94) | 13 to 20 | 17.00 (2.04) | 13 to 20 | 0.053 |

| Medication Management | 29.97 (4.00) | 19 to 33 | 31.48 (2.39) | 24 to 33 | 26.58 (4.85) | 19 to 33 | <0.001 |

| IADLS | 7.95 (0.22) | 7 to 8 | 8.00 (0.00) | 8 to 8 | 7.85 (0.38) | 7 to 8 | 0.037 |

| FAQ | 1.41 (2.43) | 0 to 10 | 0.12 (0.44) | 0 to 2 | 4.08 (2.71) | 1 to 10 | <0.001 |

| ROI Mean Composite | |||||||

| EMF | 0.53 (0.02) | 0.48 to 0.58 | 0.53 (0.02) | 0.49 to 0.57 | 0.53 (0.02) | 0.48 to 0.58 | 0.780 |

| LMF | 0.54 (0.03) | 0.49 to 0.59 | 0.55 (0.03) | 0.49 to 0.59 | 0.53 (0.03) | 0.50 to 0.58 | 0.034 |

Note: CDR=Clinical Dementia Rating; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; IADLS=Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale; FAQ=Functional Activities Questionnaire; ROI=Region of Interest; EMF=Early-Myelinated Fiber composite; LMF=Late-Myelinated Fiber composite

All SENAS scores were presented in unadjusted z-score like units where a score of zero corresponded to the mean of a demographically diverse, non-demented normative sample composed primarily of Hispanics and Whites and differences from the mean were expressed in standard deviation units.

Relationship between Functional Questionnaires and White Matter Tracts

Informant report on the FAQ (Range=0–10 out of 30 possible points, Mean=1.41±2.4) was not associated with LMF or EMF (all ps>0.05). The relationship between self-report appraisal of daily function abilities as measured by the IADLS and ROIs could not be examined due to a ceiling effect of a highly restricted range of responses on this measure (Range = 7–8 out of 8 possible points; 95% of responses were a score of 8).

Relationship between PBFAs and White Matter Tracts

Separate regression models were tested for Finances, Communication, and Medication Management as predictor variables with ROIs as the outcome variables after controlling for covariates (age, MoCA). Finances and Communication were not associated with EMF or LMF (ps>0.05). Better performance on Medication Management was significantly associated with higher mean FA values in LMF, but not EMF (EMF: p>0.05); β=0.002, t36=2.231, p=0.032, 95% CI: 0.0002, 0.0044, partial r2=0.125. To assess whether performance on Finances and Communication sections of the UPSA impacted the relationship between Medication Management and white matter tracts, an exploratory follow-up analysis controlling for Finances and Communication further strengthened this relationship; β=0.003, t34=2.668, p=0.012, 95% CI: 0.001, 0.005, partial r2=0.177. However, adding Finances and Communication did not significantly improve the model with Medication Management and covariates, ΔR2=0.067, ΔF=2.151, p=0.132.

Relationship between PBFAs and White Matter Tracts as Mediated by Cognition

Mediation models tested the SENAS Executive, Semantic, and Verbal Memory composites as mediators of the relationship between LMF and MM. Better performance on MM was associated with better performance on all three composites, but most strongly with the Semantic composite: Executive: β=2.462, t39=2.270, p=0.029, 95% CI: 0.267, 4.656, partial r2=0.120; Semantic: β=3.037, t39=3.866, p<0.001, 95% CI: 1.447, 4.627, partial r2=0.282; Verbal Memory: β=1.969, t39=2.890, p=0.006, 95% CI: 0.590, 3.348, partial r2=0.181. After controlling for age, these findings held for Semantic (t38=3.720, p=0.001) and Verbal Memory (t38=2.626, p=0.013) but not for Executive (t38=1.904, p=0.065). Mediation models did not find a significant indirect path with any of the three cognitive composite scores (bootstrapped lower- and upper-level confidence intervals included 0, all ps>0.05). Notably, only Verbal Memory was associated with LMF: β=11.343, t39=2.577, p=0.014, 95% CI: 2.432, 20.253, r2=0.149. This effect was attenuated after controlling for age (t38=1.983, p=0.055). This modest association (verbal memory) and lack of association (other domains) with ROIs explains the statistical lack of mediation effect after controlling for age in our model.

Relationship between PBFAs and White Matter Tracts by Cognitive Classification

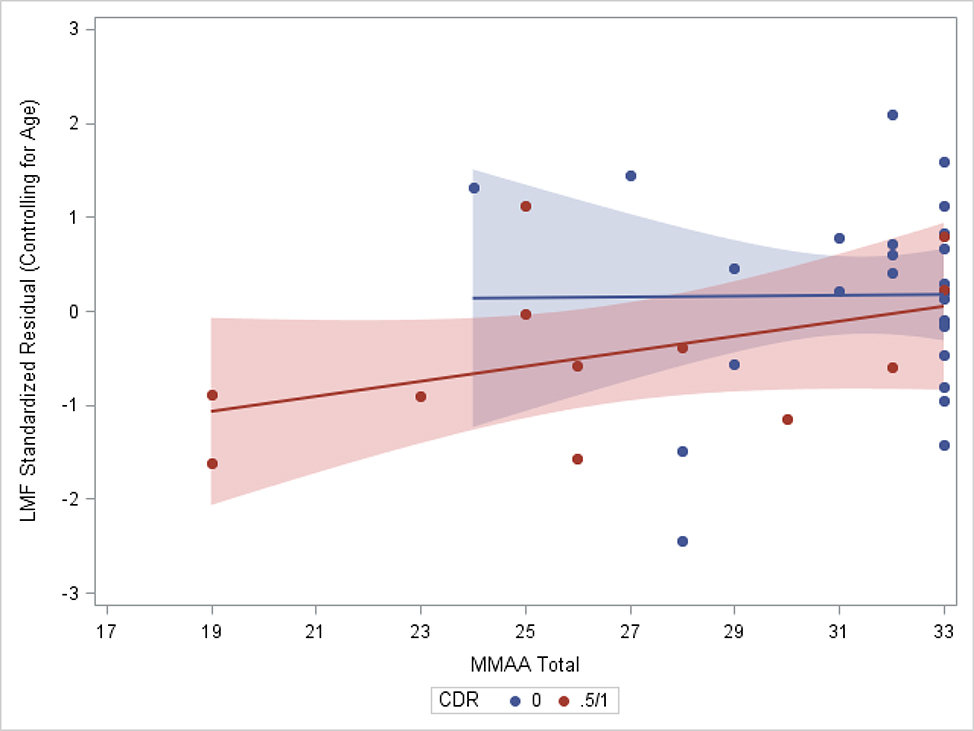

For this exploratory goal, the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Morris, 1997) scale was used to categorize individuals as having normal cognition (CDR=0; n=27) or as showing evidence of early cognitive decline (CDR=0.5 or 1; n=13). Notably, one individual was included in the latter group despite having a global score of CDR=1, suggestive of mild dementia; review of the individual’s sum of boxes score on the CDR, which was 4.5, indicated very mild symptoms and the individual received a consensus conference diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. The cognitively impaired group differed from the cognitively normal group on LMF (F1,39=4.846, p=0.034) but not on EMF (F1,39=0.079, p=0.780). Sub-group analyses with linear regression controlling for age demonstrated a significant relationship of MMAA with LMF in the cognitively impaired group only (t10=2.324, p=0.045 vs t25=0.116, p=0.909; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subgroup Comparison of the Late-Myelinating Fibers Composite Score on the Medication Management Score by Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Group. The shaded area reflects 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Consistent with the white matter retrogenesis hypothesis, we found that performance on a PBFA related to medication management was associated with LMF, but not with EMF. However, performance on PBFAs related to financial management and communication abilities were not associated with either LMF or EMF. Contrary to our hypotheses, results from mediation analysis suggested this relationship between PBFA performance and LMF was not explained by cognitive ability as measured by traditional neuropsychological tests. Moreover, this relationship between daily function and LMF was not observed with self- or informant-report measures of functional ability.

Our results are partially consistent and extend prior literature that supports a possible relationship between PBFAs and white matter integrity (Wijtenburg et al., 2017). Specifically, our findings suggest that worse performance on objective measures of medication management are sensitive to lower integrity of late-myelinated white matter fibers. Consistent with the age-related effects on both early and late myelinated fibers reported by Brickman et al. (2012), we found evidence that aging is associated with declines in the integrity of both sets of fibers, but to a greater degree in late myelinated fibers compared to early myelinated fibers. Given that late myelinated white matter fibers are more vulnerable to the aging process and are sensitive to early stages of neurodegenerative disease, results indicate that a medication management PBFA may offer a window into pathological aging processes. This has several important implications. Medication use – and particularly use of multiple medications – is generally common in older adults. Poor medication management may lead to poor health outcomes, including further decline in neuroanatomical integrity. Medication management can also be easily and quickly assessed objectively in clinical practice and followed over time, meeting dual needs of improved cognitive assessment and associated clinical care.

Notably, objective measures related to financial management and communication abilities were not sensitive to the decline in LMF integrity. While these abilities are impacted in early stages of dementia (e.g., Kenney, Margolis, Davis, & Tremont, 2019), the lack of relationship between these abilities with LMF in a healthy aging and MCI participant sample is consistent with other research. Building on previous work with Parkinson’s disease patients that found little correlation between PBFAs related to medication management and to financial management (Pirogovsky et al., 2013), researchers found medication management was sensitive to subtle functional declines in a Parkinson’s disease MCI group relative to a Parkinson’s disease normal cognition group while financial management was not (Pirogovsky et al., 2014). Moreover, the PBFAs were not associated with measures of cognitive function. Similar to the findings we present here, the authors concluded that instrumental activities of daily living may not be a monolithic domain (Pirogovsky et al., 2013) and may represent a functional domain separate from other cognitive functioning (Pirogovsky et al., 2014).

Our results suggest performance-based measures of daily function may be an early indicator of brain health. Moreover, we did not find support of a mediating role of cognition on the relationship between PBFA and white matter. Taken together with the work reported by Pirogovsky et al. (2013, 2014), it may be possible that PBFAs are tapping into a different metric than what is captured by traditional cognitive testing. Indeed, results reported by Royall and colleagues (Royall et al., 2007) suggest that cognition alone accounts for less than 20% of unique variance in functional outcomes. In relation to cognition and white matter, results by Grieve and colleagues (Grieve et al., 2007) suggest traditional cognitive testing may explain as little as 6% of variance in FA values for late-myelinating regions. In a recent systematic review of cognitive and neuropathological correlates of instrumental activities of daily living in older adults, Overdorp and colleagues (Overdorp et al., 2016) concluded that cognition and neuroanatomical changes identified by neuroimaging may contribute independently of each other to daily function, a finding supported by our results. Demanding functional assessments might be more sensitive than classic neuropsychological tests to early change for several reasons, including ecological validity, cultural appropriateness, and maybe a multifactorial nature. In light of the limitations of the current gold standard (traditional neuropsychological assessment), a broader view of cognition, predicated on functional abilities, is needed.

Notably, subjective measures of daily function, both self- and proxy-report, were not associated with white matter integrity. This further highlights the limitations of these types of measures in a healthy and MCI cohort (i.e., lack of range compared to the larger range observed on the PBFAs). These limitations also speak to the strengths of using a PBFA related to medication management in the earliest stages of suspected decline.

We interpret these preliminary findings with caution given the small sample size and no external confirmation of AD pathology. It is possible that in the context of this pilot study that meaningful associations were missed, because we were not powered to detect small effect sizes. Our sample was well educated, limiting our ability to examine the potential role of cognitive reserve proxies (e.g., years of education). In addition, while the participant sample was well characterized and the MCI sample met NIA-AA clinical criteria, biomarkers of AD pathology were not available. Nonetheless, in a small participant sample comprised of cognitively healthy and MCI individuals, associations between medication management and LMF suggest that these alterations are early and map on measurable brain changes. This study was strengthened by the use of psychometrically matched cognitive assessments validated for use in aging populations; the lack of circularity in diagnosis whereby the measures of interest included in analyses were not part of the consensus diagnosis process of the participants; and implementation of traditional self- and informant-report functional measurement that allowed for direct comparison with performance-based measures of daily function. Moreover, these findings are consistent with the growing body of literature suggesting PBFAs are sensitive to the earliest stages of neurodegeneration.

Our conclusions highlight several points: (1) a PBFA of medication management abilities is sensitive to early clinical and neuroanatomical changes known to occur in ADRD, (2) this measure is more sensitive than the self- and informant-report options typically used in ADRD research, and (3) these relationships do not appear to be mediated by performance on traditional cognitive testing. Future work is needed to extend these results in a diverse sample of individuals that can help further examine their utility and sensitivity cross-culturally. Longitudinal studies may also help elucidate the continuum of functional decline. Additionally, these studies can aid in clarifying connections between PBFAs and biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease.

Key Points.

Question: Are performance-based functional assessments (PBFAs) sensitive to early white matter changes related to neurodegeneration?

Findings: A PBFA related to medication management abilities was more sensitive to early white matter changes than traditional cognitive tests or self-/informant-report measures of daily function.

Importance: Demanding functional assessments might be more sensitive than classic assessments to early neuropathological changes.

Next Steps: Additional cross-sectional and longitudinal data in a diverse sample are needed to extend these results.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Support for this research was provided by an Alzheimer’s Association Research Fellowship (AARFD-16-440752) and NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Numbers UL1 RR025780 and UL1 TR002535, and NIH High-End Instrumentation Grant S10OD018435. Aspects of this research were supported by philanthropic funds raised for the University of Colorado Alzheimer’s and Cognition Center (CUACC). Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- Bartzokis G (2004). Age-related myelin breakdown: A developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 25(1), 5–18; author reply 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokis G, Lu PH, & Mintz J (2007). Human brain myelination and amyloid beta deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 3(2), 122–125. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickman AM, Meier IB, Korgaonkar MS, Provenzano FA, Grieve SM, Siedlecki KL, Wasserman BT, Williams LM, & Zimmerman ME (2012). Testing the white matter retrogenesis hypothesis of cognitive aging. Neurobiology of Aging, 33(8), 1699–1715. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti T, Bettcher BM, Brennan L, Libon DJ, Burke M, Duey K, Nieves C, & Wambach D (2008). Characterization of everyday functioning in mild cognitive impairment: A direct assessment approach. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 25(4), 359–365. 10.1159/000121005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TE, Koppel J, Keehlisen L, Christen E, Dreses-Werringloer U, Conejero-Goldberg C, Gordon ML, & Davies P (2010). Performance-Based Measures of Everyday Function in Mild Cognitive Impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 845–853. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieve SM, Williams LM, Paul RH, Clark CR, & Gordon E (2007). Cognitive Aging, Executive Function, and Fractional Anisotropy: A Diffusion Tensor MR Imaging Study. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 28(2), 226–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Second edition). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2017). SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, … Silverberg N (2018). NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(4), 535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekel K, Damian M, Wattmo C, Hausner L, Bullock R, Connelly PJ, Dubois B, Eriksdotter M, Ewers M, Graessel E, Kramberger MG, Law E, Mecocci P, Molinuevo JL, Nygård L, Olde-Rikkert MG, Orgogozo J-M, Pasquier F, Peres K, … Frölich L (2015). Mild cognitive impairment and deficits in instrumental activities of daily living: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 7(1), 17. 10.1186/s13195-015-0099-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney LE, Margolis SA, Davis JD, & Tremont G (2019). The Screening Utility and Ecological Validity of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery Bill Payment Subtest in Older Adults with and without Dementia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 10.1093/arclin/acz033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Zimmerman ME, Narkhede A, Nasrabady SE, Tosto G, Meier IB, Benzinger TLS, Marcus DS, Fagan AM, Fox NC, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Buckles V, Ghetti B, McDade E, Martins RN, Saykin AJ, Masters CL, Ringman JM, … Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. (2018). White matter hyperintensities and the mediating role of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in dominantly-inherited Alzheimer’s disease. PloS One, 13(5), e0195838. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GA, Zoller AS, Lorius N, Amariglio RE, Locascio JJ, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, & Rentz DM (2015). Functional Activities Questionnaire items that best discriminate and predict progression from clinically normal to mild cognitive impairment. Current Alzheimer Research, 12(5), 493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, & Patterson TL (2007). Development of a Brief Scale of Everyday Functioning in Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(6), 1364–1372. 10.1093/schbul/sbm014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1997). Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA, 9 Suppl 1, 173–176; discussion 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Reed BR, Haan MN, & González H (2005). Spanish and English Neuropsychological Assessment Scales: Relationship to demographics, language, cognition, and independent function. Neuropsychology, 19(4), 466–475. 10.1037/0894-4105.19.4.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrabady SE, Rizvi B, Goldman JE, & Brickman AM (2018). White matter changes in Alzheimer’s disease: A focus on myelin and oligodendrocytes. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 6. 10.1186/s40478-018-0515-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, & Chertkow H (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment: MOCA: A BRIEF SCREENING TOOL FOR MCI. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overdorp EJ, Kessels RPC, Claassen JA, & Oosterman JM (2016). The Combined Effect of Neuropsychological and Neuropathological Deficits on Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychology Review, 26(1), 92–106. 10.1007/s11065-015-9312-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, & Jeste DV (2001). UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 27(2), 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson Thomas L., Lacro J, McKibbin CL, Moscona S, Hughs T, & Jeste DV (2002). Medication management ability assessment: Results from a performance-based measure in older outpatients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(1), 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, & Kokmen E (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology, 56(3), 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Chance JM, & Filos S (1982). Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of Gerontology, 37(3), 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirogovsky E, Martinez-Hannon M, Schiehser DM, Lessig SL, Song DD, Litvan I, & Filoteo JV (2013). Predictors of performance-based measures of instrumental activities of daily living in nondemented patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 35(9), 926–933. 10.1080/13803395.2013.838940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirogovsky E, Schiehser DM, Obtera KM, Burke MM, Lessig SL, Song DD, Litvan I, & Filoteo JV (2014). Instrumental activities of daily living are impaired in Parkinson’s disease patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology, 28(2), 229–237. 10.1037/neu0000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, Kluger A, Franssen E, Wegiel J, & de Leon MJ (2008). Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A historical perspective. International Psychogeriatrics / IPA, 20(1), 18–31. 10.1017/S1041610207006394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royall DR, Lauterbach EC, Kaufer D, Malloy P, Coburn KL, & Black KJ (2007). The Cognitive Correlates of Functional Status: A Review From the Committee on Research of the American Neuropsychiatric Association. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 19(3), 249–265. 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman SC, & Giovannetti T (2015). The Potential utility of eye movements in the detection and characterization of everyday functional difficulties in mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology Review, 25(2), 199–215. 10.1007/s11065-015-9283-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman LM, Pretzer-Aboff I, Anderson KE, Stevenson R, Vaughan CG, Gruber-Baldini AL, Reich SG, & Weiner WJ (2006). Subjective report versus objective measurement of activities of daily living in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, 21(6), 794–799. 10.1002/mds.20803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, … Phelps CH (2011). Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(3), 280–292. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stricker NH, Schweinsburg BC, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga CE, Bangen KJ, Haaland KY, Frank LR, Salmon DP, & Bondi MW (2009). Decreased white matter integrity in late-myelinating fiber pathways in Alzheimer’s disease supports retrogenesis. NeuroImage, 45(1), 10–16. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida CA, Vo TT, Van Etten EJ, & Schmitter-Edgecombe M (2018). Medication Management Performance and Associated Cognitive Correlates in Healthy Older Adults and Older Adults with aMCI. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 34(3), 290–300. 10.1093/arclin/acy038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng E, Becker BW, Woo E, Cummings JL, & Lu PH (2010). Subtle Deficits in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Subtypes of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30(3), 189–197. 10.1159/000313540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2009). MRI and CSF biomarkers in normal, MCI, and AD subjects: Predicting future clinical change. Neurology, 73(4), 294–301. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181af79fb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijtenburg SA, Wright SN, Korenic SA, Gaston FE, Ndubuizu N, Chiappelli J, McMahon RP, Chen H, Savransky A, Du X, Wang DJJ, Kochunov P, Hong LE, & Rowland LM (2017). Altered Glutamate and Regional Cerebral Blood Flow Levels in Schizophrenia: A 1 H-MRS and pCASL study. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(2), 562–571. 10.1038/npp.2016.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]