Abstract

Objectives

The dearth of research on age-related differences in risk factors for tobacco use disorder (TUD) among sexual minorities, particularly among older adults, can obscure the differential needs of sexual minority age groups for tobacco prevention and cessation. We examined the association of cumulative ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination with moderate-to-severe TUD among U.S. sexual minority adults aged 50 years and older.

Method

We analyzed cross-sectional data from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (n = 36,309 U.S. adults). Our sample consisted of 1,258 adults (lesbian/gay-, bisexual-, and heterosexual-identified adults with same-sex attraction/behavior) aged ≥50 years. Multivariable logistic regression analyses estimated the association of cumulative lifetime ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination with past-year moderate-to-severe TUD and tested whether the association differed for adults aged 50–64 years versus those aged ≥65 years.

Results

An estimated 8.1% of the sample met criteria for moderate-to-severe TUD. Lifetime ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination was not significantly associated with moderate-to-severe TUD for adults aged ≥50 years. However, a significant 2-way interaction was found between discrimination and age. In age-stratified analyses, greater discrimination was significantly associated with greater risk for moderate-to-severe TUD for adults aged ≥65 years, but not adults aged 50–64 years.

Discussion

Greater cumulative discrimination based on ethnicity/race and sexual orientation was associated with increased risk for moderate-to-severe TUD among sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years. Our findings underscore the importance of age considerations in understanding the role of discrimination in the assessment and treatment of TUD.

Keywords: Age, Discrimination, Sexual minority, Tobacco, Tobacco use disorder

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality worldwide (World Health Organization, 2011). Over 480,000 U.S. deaths annually can be attributed to cigarette smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Tobacco use disorder (TUD) is a clinical diagnosis assigned to individuals resulting from their use of tobacco and/or nicotine products. There are varying levels of TUD severity, including mild (two to three symptoms), moderate (four to five symptoms), and severe (six or more symptoms; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The prevalence of past-year TUD among U.S. adults overall is 20% (Chou et al., 2016).

Compared to heterosexual adults, sexual minority adults (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual) are at higher risk for tobacco use (Hinds et al., 2019; Hoffman et al., 2018; McCabe et al., 2018, 2019; Schuler et al., 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014) and are more likely to meet criteria for TUD (Boyd et al., 2019; Kerridge et al., 2017; McCabe et al., 2019; Rice et al., 2019). Smoking differences persist in mid to late adulthood, with sexual minority adults aged ≥50 years having increased odds of smoking relative to their heterosexual counterparts (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). Extant research has found variability in substance use across sexual orientation dimensions (McCabe et al., 2009) as well as age-related differences in risk for TUD among sexual minority adults (Evans-Polce et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2018). Bisexuals and individuals who are unsure about their sexual identity have particularly increased risk for severe TUD (Boyd et al., 2019). TUD is more prevalent among younger gay/lesbian women and gay men, whereas bisexual men and women have a high prevalence of TUD across all age groups (McCabe et al., 2018).

The Minority Stress Model (Meyer, 1995) posits that in addition to everyday life stresses, sexual minority individuals’ exposure to homophobic and hostile social environments related to their minority status may contribute to excess stress and health risk behaviors, which in turn results in adverse health consequences. Past-year sexual orientation discrimination (McCabe et al., 2019; Ylioja et al., 2018) and structural stigma (societal-level conditions that constrain individuals’ opportunities; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014) are associated with risk for tobacco use and TUD. Previous research has identified ethnic/racial discrimination as a risk factor for negative health outcomes (Krieger & Sidney, 1996), including tobacco use (Bennett et al., 2005; Chavez et al., 2015). Additionally, the Dynamic Diathesis–Stress Model suggests that the relationship between inherited risk factors and environmental stressors can influence the onset and time course of substance use disorders (Windle, 2010). It emphasizes the additive nature of environmental stressors as part of a multifactorial understanding of substance use disorders. Both conceptual models inform our examination of cumulative ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination as a potential risk factor for TUD.

To date, limited attention has been paid to sexual minority adults in the ≥65 years age category, an underserved population whose needs warrant further inquiry (Institute of Medicine, 2011). Many sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years came of age during a time when same-sex identity, attraction, or behavior were pathologized in the United States. These adults grew up in environments that were less supportive (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). No studies have considered the cumulative association of discrimination (based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) with moderate-to-severe TUD among U.S. sexual minority adults across the 50–64 and ≥65 age groups. To fill this gap, this study examines discrimination as a potential risk factor for moderate-to-severe TUD among U.S. sexual minority adults aged ≥50 years, and assesses whether the association differed for participants aged 50–64 years compared to those aged ≥65 years.

Method

Participants

Our data come from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III; n = 36,309 U.S. adults aged ≥18 years). More information about the NESARC-III methodology can be found elsewhere (Grant et al., 2015). We restricted our sample to sexual minorities (defined as lesbian/gay-, bisexual-, heterosexual-identified individuals with same-sex attraction/behavior, and individuals who were not sure about their sexual identity; Boyd et al., 2019; Evans-Polce et al., 2020), aged ≥50 years. To ensure adequate sample sizes for subgroup analyses, we excluded participants who identified as Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 58) or American Indian/Alaska Native (n = 23). Our final sample included 1,258 participants.

Measures

Dependent variable

Past-year Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) TUD was created from 11 symptoms consistent with the DSM-5 criteria for TUD (Supplementary Table 1). Participants who endorsed two or more symptoms met criteria for past-year any TUD and those endorsing four or more symptoms met criteria for past-year moderate-to-severe TUD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Sexual orientation

Participants were asked to describe themselves as heterosexual (straight), gay/lesbian, bisexual, or not sure. Participants’ sexual behavior (only with opposite sex, with both sexes, and never had sex) and sexual attraction (only attracted to females, mostly attracted to females, equally attracted to both sexes, mostly attracted to males, and only attracted to males) were also assessed to determine sexual minority status as described above.

Minority stress-related variables

Adapted from the Experiences of Discrimination scale (Krieger et al., 2005), participants were asked about their past-year and prior-to-past-year experiences related to ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination. Non-Hispanic/Latino participants were asked about ethnic/racial discrimination generally, whereas Hispanic/Latino participants received discrimination items specifically related to their Hispanic/Latino identity. Only sexual minorities received questions about sexual orientation discrimination. The lifetime ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination measure was created by summing the responses to ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination items within the past-year and/or prior-to-past-year, with a possible range from 0 to 96.

Additional minority stress-related variables included the social support scale (based on the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List [Cohen et al., 1985], with a possible range of 0–36), stressful life events (based on the Stressful Life Events Scale [Ruan et al., 2008], consisting of none, 1–2, and ≥3 stressful life events), any past-year DSM-5 anxiety disorder, and any past-year DSM-5 mood disorder.

Sociodemographic variables

These included age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, urbanicity, geographic region, relationship status, and religiosity/spirituality.

Statistical Analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression analyses to assess the relationship of lifetime discrimination with moderate-to-severe TUD among the overall sample and for each age group (50–64 years and ≥65 years). We tested the two-way interaction between lifetime discrimination and age. Given the number of models fitted, we evaluated significance at the 0.01 level.

Additional details about the sexual orientation and sociodemographic variables and statistical analyses are available in the Supplementary File.

Results

An estimated 8.1% of participants met criteria for moderate-to-severe TUD. Notably, sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years were significantly less likely to meet criteria for moderate-to-severe TUD and reported lower mean lifetime discrimination (based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) relative to adults aged 50–64 years old (Table 1). Multiple imputation analyses (Supplementary Table 2) revealed no differences in these results after multiple imputation of missing values.

Table 1.

Estimated Distributions of Key Study Measures for Sexual Minoritya Adults in the NESARC-III by Age Categories

| Variable Categories | Age categories | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 50 years (overall sample) | Age 50–64 years | Age ≥ 65 years | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Past-year any TUD** | 221 (15.8) | 179 (19.8) | 42 (9.3) |

| Past-year moderate-to-severe TUD** | 127 (8.1) | 106 (10.9) | 21 (3.6) |

| Lifetime ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination scale (0–96), mean (SE)† | 4.4 (0.3) | 5.6 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 579 (47.4) | 377 (49.0) | 202 (44.8) |

| Female | 679 (52.6) | 434 (51.0) | 245 (55.2) |

| Sexual orientation** | |||

| Heterosexual-identified with same-sex attraction and/or behavior | 897 (73.9) | 543 (68.6) | 354 (82.4) |

| Lesbian/gay-identified | 184 (14.4) | 146 (17.9) | 38 (8.5) |

| Bisexual-identified | 96 (5.9) | 73 (7.6) | 23 (3.2) |

| Not sure | 81 (5.9) | 49 (5.9) | 32 (5.9) |

| Race/ethnicity** | |||

| White | 813 (80.6) | 479 (76.7) | 334 (86.8) |

| African American | 233 (10.9) | 183 (13.9) | 50 (6.2) |

| Hispanic | 131(8.5) | 93 (9.4) | 38 (7.0) |

| Educational attainment** | |||

| High school degree or less | 489 (37.8) | 282 (32.4) | 207 (46.7) |

| Some college | 255 (18.7) | 177 (20.7) | 78 (15.6) |

| College degree or higher | 514 (43.5) | 352 (47.0) | 162 (37.7) |

| Urbanicity | |||

| Urban | 1,058 (80.7) | 687 (80.8) | 371 (80.5) |

| Rural | 200 (19.3) | 124 (19.2) | 76 (19.5) |

| Geographic region | |||

| Northeast | 225 (21.6) | 136 (21.0) | 89 (22.5) |

| Midwest | 249 (19.7) | 160 (20.1) | 89 (19.0) |

| South | 408 (31.2) | 272 (32.0) | 136 (29.8) |

| West | 376 (27.6) | 243 (26.9) | 133 (28.7) |

| Social support scale (0–36), mean (SE) | 28.1 (0.2) | 28.2 (0.3) | 27.9 (0.3) |

| Relationship status** | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 475 (52.0) | 308 (51.5) | 167 (53.0) |

| Widowed | 162 (11.2) | 47 (4.9) | 115 (21.6) |

| Divorced | 283 (17.4) | 197 (19.4) | 86 (14.2) |

| Separated | 65 (3.8) | 52 (4.9) | 13 (2.0) |

| Never married | 273 (15.5) | 207 (19.3) | 66 (9.2) |

| Religiosity/spirituality | |||

| Very important | 787 (59.7) | 508 (58.6) | 279 (61.4) |

| Somewhat important | 284 (24.7) | 185 (26.0) | 99 (24.7) |

| Not very important | 94 (7.4) | 57 (6.5) | 37 (9.0) |

| Not important at all | 92 (8.3) | 61 (9.0) | 31 (7.1) |

| Stressful life events** | |||

| None | 400 (33.8) | 206 (26.7) | 194 (45.6) |

| 1–2 | 579 (46.0) | 368 (45.7) | 211 (46.5) |

| 3+ | 267 (20.1) | 229 (27.6) | 38 (8.0) |

| Any past-year DSM-5 anxiety disorder* | |||

| No | 1,047 (83.6) | 657 (81.2) | 390 (87.5) |

| Yes | 211 (16.4) | 154 (18.8) | 57 (12.5) |

| Any past-year DSM-5 mood disorder* | |||

| No | 1,069 (87.2) | 664 (84.6) | 405 (91.5) |

| Yes | 189 (12.8) | 147 (15.4) | 42 (8.5) |

Notes. DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition; NESARC-III = National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions-III; TUD = tobacco use disorder. The Rao–Scott chi squares were calculated from the bivariate analysis of the variables, accounting for the complex survey features of the NESARC-III. The p values are calculated by survey design-based F test of significance.

aSexual minorities defined as lesbian/gay-identified, bisexual-identified, heterosexual-identified people with same-sex attraction and/or behavior, and those who were not sure about their sexual identity.

Rao–Scott chi–squared test: *p < .01, **p < .001. Wald F test: †p < .001.

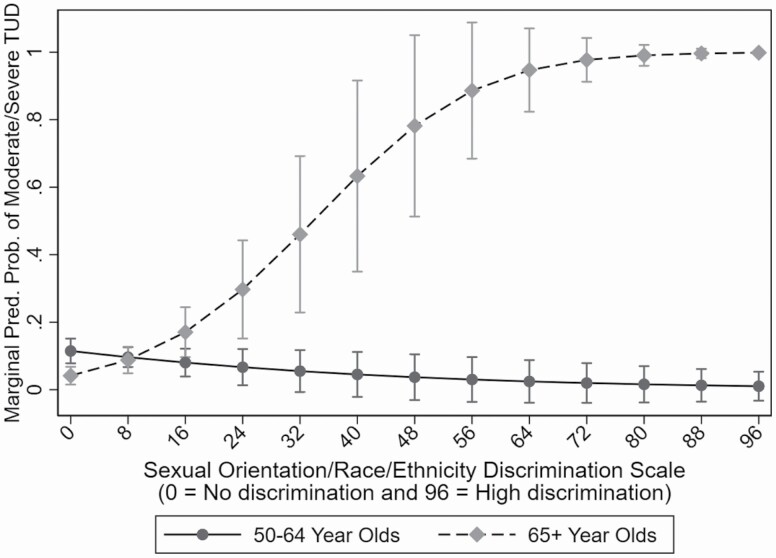

Table 2 displays results of the logistic regression analyses examining the association of lifetime discrimination with moderate-to-severe TUD among the overall sample (Model 1), adults aged 50–64 years (Model 2), and adults aged ≥65 years (Model 3). The relationship between discrimination and moderate-to-severe TUD was not significant in the overall sample (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.00–1.00). However, a significant interaction was found between discrimination and age (Figure 1). In age-stratified analyses, lifetime discrimination was significantly associated with moderate-to-severe TUD for sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years (Model 3; AOR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.00–1.20) but not for adults aged 50–64 years old (Model 2; AOR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.90–1.00). Similar findings emerged in analyses that used multiple imputation (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 2.

Estimated Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Describing Associations Between Lifetime Discrimination (Based on Race/Ethnicity and Sexual Orientation) and Moderate-to-Severe Tobacco Use Disorder Among Sexual Minority Adults

| Variable Categories | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 50 years (overall sample) | Age 50–64 years |

Age ≥ 65 years |

||||

| N = 968 | N = 633 | N = 325 | ||||

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Lifetime ethnic/racial discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination scale | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0, 1.2* |

| Age | — | — | — | — | ||

| 50–64 | Ref. | Ref. | — | — | — | — |

| 65+ | 0.6 | 0.3, 1.1 | — | — | — | — |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.5, 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.1, 1.3 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual-identified with same-sex attraction and/or behavior | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Lesbian/gay-identified | 0.9 | 0.3, 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.3, 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.3, 10.0 |

| Bisexual-identified | 1.5 | 0.6, 4.1 | 1.7 | 0.6, 5.0 | 2.1 | 0.1, 85.1 |

| Not sure | 1.8 | 0.7, 4.8 | 1.9 | 0.7, 5.8 | 0.5 | 0.1, 2.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| African American | 1.6 | 0.8, 3.1 | 1.3 | 0.6, 2.8 | 5.3 | 0.7, 42.1 |

| Hispanic | 0.6 | 0.3, 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.2, 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.0, 24.4 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| High school degree or less | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some college | 0.7 | 0.4, 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.1, 4.1 |

| College degree or higher | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.4* | 0.2 | 0.1, 0.4* | 0.2 | 0.0, 1.0 |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Urban | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Rural | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.3, 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.1, 9.8 |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Northeast | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Midwest | 2.2 | 0.8, 6.0 | 2.2 | 0.7, 6.6 | 3.3 | 0.4, 24.1 |

| South | 0.9 | 0.3, 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.3, 2.1 | 2.0 | 0.3, 12.2 |

| West | 1.1 | 0.4, 3.1 | 1.1 | 0.3, 3.3 | 1.5 | 0.4, 6.5 |

| Social support scale | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9, 1.1 |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Married/cohabitating | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Widowed | 0.6 | 0.2, 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.3, 5.3 | 0.2 | 0.0, 2.0 |

| Divorced | 1.5 | 0.8, 3.0 | 1.7 | 0.8, 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.1, 6.0 |

| Separated | 1.7 | 0.6, 4.3 | 2.4 | 0.9, 6.8 | N/A | N/A |

| Never married | 2.3 | 1.2, 4.5 | 2.7 | 1.3, 5.6* | 1.0 | 0.2, 4.7 |

| Religiosity/spirituality | ||||||

| Very important | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Somewhat important | 1.5 | 0.8, 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.5, 2.6 | 4.4 | 1.1, 18.0 |

| Not very important | 1.1 | 0.4, 3.2 | 1.1 | 0.3, 3.7 | 2.3 | 0.2, 24.4 |

| Not important at all | 2.0 | 0.8, 5.1 | 1.8 | 0.6, 5.3 | 5.9 | 0.2, 164.7 |

| Stressful life events | ||||||

| None | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1–2 | 1.4 | 0.7, 3.0 | 1.3 | 0.6, 3.1 | 1.7 | 0.5, 5.6 |

| 3+ | 3.5 | 1.8, 7.2* | 2.8 | 1.2, 6.1 | 15.7 | 3.3, 73.3 |

| Any past-year DSM-5 anxiety disorder | ||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.7 | 0.9, 3.2 | 1.6 | 0.7, 3.4 | 4.0 | 0.8, 19.6 |

| Any past-year DSM-5 mood disorder | ||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 3.3 | 1.6, 6.9* | 3.3 | 1.5, 7.2* | 3.5 | 0.5, 22.9 |

| Goodness-of-fit test | p = .340 | p < .001 | p < .001 |

Notes: AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition.

*p < .01.

Figure 1.

Predictive margins of moderate-to-severe TUD by age and lifetime discrimination (based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation), with 95% confidence intervals. TUD = tobacco use disorder.

Discussion

Sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years were less likely to report lifetime discrimination (based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) and less likely to meet criteria for moderate-to-severe TUD. Yet, those who were exposed to higher levels of lifetime discrimination had increased risk for moderate-to-severe TUD. While our study is not able to disentangle age and cohort effects, our findings are consistent with research that showed cohort differences among sexual minority adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). For sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years who came of age when same-sex behavior/attraction was defined as a DSM psychiatric illness, the stress from discrimination may have contributed to their TUD. These findings provide support for the Minority Stress and Dynamic Diathesis–Stress models by demonstrating that excess stress in the social environment related to minority status and the additive nature of these stressors can influence TUD severity.

Health care providers and smoking cessation specialists are reminded that minority stressors influence their clients’ health behaviors. It is important to avoid assumptions about sexual orientation and health behaviors because not all sexual minorities identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Some individuals conceal their identity as a way of managing stigma and discrimination (Institute of Medicine, 2011) and identity disclosure may vary based on social circumstances (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014). The vast majority of sexual minority adults aged ≥65 years in our sample (87.5%) identified as heterosexuals with same-sex attraction and/or behavior. Given the historical climate when these older individuals came of age, they may experience greater internalized homophobia. Furthermore, ethnic/racial discrimination remains a pervasive problem in the United States. The cumulative stress from multiple types of discrimination likely increased their risk for TUD. All health care providers should create inclusive environments in which clients feel safe. Increasing access to smoking cessation programs that are affirming of ethnic/racial and sexual minority identities can promote physical and mental well-being among adults aged ≥65 years.

The strengths of this study include the use of a large, nationally representative, probability-based sample of U.S. sexual minority adults; validated measures of discrimination (Krieger et al., 2005; Ruan et al., 2008); and survey items that assessed multiple dimensions of sexual orientation, allowing us to include heterosexual-identified sexual minorities in our sample. Several limitations warrant comment. We used a lifetime measure of sexual behavior, which did not discern between recent versus past behavior. In additional analyses, we included past-year sexual behavior to assess sexual minority status and this did not make any difference to our results (available upon request). Inferences about causality are limited because of the cross-sectional design of this study. We were unable to examine certain racial/ethnic groups due to small cell sizes. We found that the goodness-of-fit of the models was lacking in some cases, but the small sample size for this subpopulation combined with the relatively rare probability of moderate-to-severe TUD generally prevented us from including several additional predictors (e.g., interactions) in the fitted models to improve the fit. We did find evidence of improved prediction associated with the variables included, but the identification of additional important minority stress-related predictors for this subpopulation (e.g., internalized homophobia) is an important direction for future work. We conducted sensitivity analyses by controlling for self-reported health status in our models and this did not change our primary findings (available upon request).

The discrimination items did not assess the severity of the discrimination experienced. Furthermore, these items focused on selected individual-level rather than structural-level discrimination, and thus may underrepresent the scope of discrimination experienced by sexual minority adults. Our lifetime discrimination measure did not differentiate between recent versus distant past discrimination experiences. In additional analyses, we tested past-year and prior-to-past-year discrimination (based on race/ethnicity and sexual orientation) in separate models. No significant associations were found between past-year discrimination and moderate-to-severe TUD in the overall sample and in age-stratified analyses. Similar to our main results, prior-to-past-year discrimination was not significantly associated with moderate-to-severe TUD for adults aged ≥50 years. However, a significant two-way interaction was found between discrimination and age. In age-stratified analyses, greater prior-to-past-year discrimination was associated with increased risk for moderate-to-severe TUD for adults aged ≥65 years, but not adults aged 50–64 years (available upon request). Future research should include a larger sample of adults aged ≥65 years to explore the association of recent versus distant past discrimination experiences with health risk behaviors and examine potential generational differences on the influence of structural-level discrimination, stressors (e.g., internalized homophobia), and resilience (e.g., family/community support) encountered by sexual minorities.

Our findings underscore the importance of age considerations in understanding the role of discrimination in the assessment and treatment of TUD. Discrimination increases the risk of moderate-to-severe TUD among older sexual minority adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editorial team for their detailed review and helpful suggestions to earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by research grants from the National Cancer Institute (grant numbers R01CA203809 and R01CA212517) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant numbers R01DA036541, R01DA043696, and R21DA051388) at the National Institutes of Health. The content of the manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, or the U.S. Government. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

L. Kcomt conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the original manuscript. R. J. Evans-Polce assisted with the conceptualization of the study, critically reviewed, and edited the manuscript. C. W. Engstrom conducted the analyses and drafted the original manuscript. B. T. West provided supervision, assisted with the interpretation of results, critically reviewed, and edited the manuscript. C. J. Boyd critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. S. E. McCabe assisted with the conceptualization of the study, interpretation of results, critically reviewed the manuscript, and provided supervision for the study. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, G. G., Wolin, K. Y., Robinson, E. L., Fowler, S., & Edwards, C. L. (2005). Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 238–240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, C. J., Veliz, P. T., Stephenson, R., Hughes, T. L., & McCabe, S. E. (2019). Severity of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders among sexual minority individuals and their “not sure” counterparts. LGBT Health, 6(1), 15–22. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, L. J., Ornelas, I. J., Lyles, C. R., & Williams, E. C. (2015). Racial/ethnic workplace discrimination: Association with tobacco and alcohol use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(1), 42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., Huang, B., Ruan, W. J., Zhang, H., Jung, J., Saha, T. D., Pickering, R. P., & Grant, B. F. (2016). The epidemiology of DSM-5 nicotine use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions—III. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(10), 1404–1412. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S., Mermelstein, R., Kamarck, T., & Hoberman, H. M.(1985). Measuring the functional components of social support. In Sarason I. G. & Sarason B. R. (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research and applications (Vol. 24, pp. 73–94). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce, R. J., Veliz, P. T., Boyd, C. J., Hughes, T. L., & McCabe, S. E. (2020). Associations between sexual orientation discrimination and substance use disorders: Differences by age in US adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(1), 101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01694-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Bryan, A. E. B., Jen, S., Goldsen, J., Kim, H.-J., & Muraco, A. (2017). The unfolding of LGBT lives: Key events associated with health and well-being in later life. The Gerontologist, 57(suppl. 1), S15–S29. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H. J., Barkan, S. E., Muraco, A., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Simoni, J. M., Kim, H. J., Lehavot, K., Walters, K. L., Yang, J., Hoy-Ellis, C. P., & Muraco, A. (2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–663. doi: 10.1037/ort0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B. F., Chu, A., Sigman, R., Amsbary, M., Kali, J., Sugawara, Y., Jiao, R., Ren, W., & Goldstein, R. (2015). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions—III (NESARC-III): Source and accuracy statement. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Jun, H. J., Corliss, H. L., & Austin, S. B. (2014). Structural stigma and cigarette smoking in a prospective cohort study of sexual minority and heterosexual youth. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 48–56. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9548-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, J. T., Loukas, A., & Perry, C. L. (2019). Explaining sexual minority young adult cigarette smoking disparities. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 371–381. doi: 10.1037/adb0000465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, L., Delahanty, J., Johnson, S. E., & Zhao, X. (2018). Sexual and gender minority cigarette smoking disparities: An analysis of 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data. Preventive Medicine, 113, 109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/13128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge, B. T., Pickering, R. P., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Chou, S. P., Zhang, H., Jung, J., & Hasin, D. S. (2017). Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 170, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N., & Sidney, S. (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health, 86(10), 1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N., Smith, K., Naishadham, D., Hartman, C., & Barbeau, E. M. (2005). Experiences of Discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 61(7), 1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., Bostwick, W. B., West, B. T., & Boyd, C. J. (2009). Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 104(8), 1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, S. E., Hughes, T. L., Matthews, A. K., Lee, J. G. L., West, B. T., Boyd, C. J., & Arslanian-Engoren, C. (2019). Sexual orientation discrimination and tobacco use disparities in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 21(4), 523–531. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, S. E., Matthews, A. K., Lee, J. G. L., Veliz, P., Hughes, T. L., & Boyd, C. J. (2018). Tobacco use and sexual orientation in a national cross-sectional study: Age, race/ethnicity, and sexual identity-attraction differences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 54(6), 736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. doi: 10.2307/2137286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice, C. E., Vasilenko, S. A., Fish, J. N., & Lanza, S. T. (2019). Sexual minority health disparities: An examination of age-related trends across adulthood in a national cross-sectional sample. Annals of Epidemiology, 31, 20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W. J., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Smith, S. M., Saha, T. D., Pickering, R. P., Dawson, D. A., Huang, B., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2008). The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule—IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1–3), 27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, M. S., Rice, C. E., Evans-Polce, R. J., & Collins, R. L. (2018). Disparities in substance use behaviors and disorders among adult sexual minorities by age, gender, and sexual identity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 189, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . (2014). The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the surgeon general. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. doi: 10.1037/e510072014-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Windle, M. (2010). A multilevel developmental contextual approach to substance use and addiction. BioSocieties, 5, 124–136. doi: 10.1057/biosoc.2009.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2011). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: Warning about the dangers of tobacco. World Health Organization. www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Ylioja, T., Cochran, G., Woodford, M. R., & Renn, K. A. (2018). Frequent experience of LGBQ microaggression on campus associated with smoking among sexual minority college students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(3), 340–346. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.