Abstract

Background:

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is characterized by restrictive eating and failure to meet nutritional needs but is distinct from anorexia nervosa (AN) because restriction is not motivated by weight/shape concerns. We examined levels of orexigenic ghrelin and anorexigenic peptide YY (PYY) in young females with ARFID, AN and healthy controls (HC).

Methods:

94 females (22 low-weight ARFID, 40 typical/atypical AN, and 32 HC ages 10–22 years) underwent fasting blood draws for total ghrelin and total PYY. A subset also provided blood 30, 60 and 120 minutes after a standardized meal.

Results:

Females with ARFID ate less than those with AN or HC (ps<.012); were younger (14.4±3.2 years) than those with AN (18.9±3.1 years) and HC (17.4±3.1 years) (ps<.003) and at a lower Tanner stage (3.1±1.5) than AN (4.5±1.1;) and HC (4.4±1.1; ps<.005), but did not differ in BMI percentiles or BMI Z-scores from AN (ps>.44). Fasting and postprandial ghrelin were lower in ARFID versus AN (ps≤.015), but not HC (ps≥.62). Fasting and postprandial PYY did not differ between ARFID versus AN or HC (ps≥.127); ARFID did not demonstrate the sustained high PYY levels post-meal observed in those with AN and HC. Secondary analyses controlling age or Tanner stage and calories consumed showed similar results. Exploratory analyses suggest that the timing of the PYY peak in ARFID is earlier than HC, showing a peak PYY level 30 minutes post-meal (p=.037).

Conclusions:

ARFID and AN appear to have distinct patterns of secretion of gut-derived appetite-regulating hormones that may aid in differential diagnosis and provide new treatment targets.

Keywords: Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, ARFID, anorexia nervosa, ghrelin, PYY

1. INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN) and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) are psychiatric disorders defined by restrictive eating (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Thomas & Eddy, 2019). Criteria for AN include extreme fear of weight gain and/or body image disturbance despite persistent low body weight (APA, 2013). In contrast, dietary restriction in ARFID is motivated by sensory sensitivities to foods, disinterest in food/eating or low appetite, and/or phobia of vomiting, choking, or gastrointestinal (GI) pain (APA, 2013; Thomas & Eddy, 2019). Reports of lifetime prevalence of AN range from 1.2% to 2.2% and 0.6% for adolescent girls by age 20 (Smink et al., 2012). ARFID may be even more common in children and adolescents as one community study reported that 3% of children ages 8–13 met ARFID criteria and the prevalence of youth with ARFID presenting for treatment at pediatric hospitals and eating disorder programs ranges from 5% to 23% (Mammel and Ornstein, 2017) (Mammel & Ornstein, 2017). AN is a highly debilitating disease, in part because low weight and malnutrition occur in the context of severe morbidity (psychiatric, metabolic, endocrine (Lawson et al., 2011; Sedlackova et al., 2012; Singhal and Misra, 2014) and premature mortality (Keshaviah et al., 2014). Further, AN has among the highest mortality rate among mental disorders at 0.51% per year (Smink et al., 2021). Youth with ARFID are commonly as underweight and malnourished as those with AN (Becker et al., 2019; Nicely et al., 2014), but because ARFID is a recently defined disorder (APA, 2013), mortality rates are not yet known. However, one study reported that 34% of patients with ARFID required hospitalization due to low-weight and unstable vital signs (Norris et al., 2014). In addition, the impact of ARFID on body systems involved in appetite regulation is less well-understood. However, early findings suggest low levels of leptin (a hormone released by fat in proportion to energy stores), similar to AN (Aulinas et al., 2020). The concomitant risks of malnutrition and low weight suggest equivalent urgency in determining underlying mechanisms that maintain symptoms in low-weight ARFID to inform psychiatric management of this complex illness.

Assessment of appetite-regulating hormones secreted in response to nutrients in the gut represents an important avenue for examining disruptions in eating behaviors (Schorr and Miller, 2017; Singhal and Misra, 2014). Aberrant hormone levels are well-documented in AN and may be both adaptive to chronic starvation and an explanatory mechanism maintaining dietary restriction (Schorr and Miller, 2017). No investigations have examined levels of gastrointestinal-derived appetite-regulating hormones in ARFID.

Ghrelin is a 28-amino-acid peptide secreted in a pulsatile manner primarily by endocrine cells in the stomach and GI tract with a primary orexigenic (i.e., appetite stimulating) effect (Gil-Campos et al., 2006; Tortorella et al., 2014). Circulating concentrations of total ghrelin increase with fasting and decrease postprandially in healthy individuals and those with AN (Gil-Campos et al., 2006; Monteleone et al., 2003), reaching a nadir 30 to 120 minutes after eating (Nakahara et al., 2007; Sedlackova et al., 2012; Stock et al., 2005). Changes in ghrelin levels after weight gain (Otto et al., 2005) or loss (Kelishadi et al., 2008) suggest its relevance to understanding both acute and chronic feeding behaviors (Gil-Campos et al., 2006; Nakahara et al., 2007). Individuals with AN have elevated fasting and postprandial ghrelin compared to healthy controls (HC; Nakahara et al., 2007; Schorr & Miller, 2017; Singhal & Misra, 2014) and AN and HC both show reductions in ghrelin after eating, but nadir postprandial ghrelin levels remain higher in AN (Nakahara et al., 2007). Endogenous ghrelin concentrations are inversely related to body mass index (BMI) in AN, suggesting that this is an adaptive response to promote food intake in a low-weight state (Misra et al., 2005). Consistently, weight gain in AN results in reductions in fasting ghrelin (Otto et al., 2005). Therefore, elevated ghrelin levels in AN are considered a consequence of malnutrition and an adaptive response to enhance appetite signaling (Schorr and Miller, 2017; Singhal and Misra, 2014). However, these elevations do not coincide with improved appetite or nutritional intake (Holsen et al., 2014), leading to the hypothesis that AN is characterized by ghrelin resistance (Singhal and Misra, 2014).

Although research is lacking regarding ghrelin levels in ARFID, previous research on feeding disorders provided the foundation for ARFID diagnostic criteria (APA, 2013; Bryant-Waugh, Markham, Kreipe, & Walsh, 2010; Thomas & Eddy, 2019), and some data exist for young children with avoidant/restrictive eating. One study (Tannenbaum et al., 2009) reported that total ghrelin levels in infants with inadequate growth were higher than those in healthy infants and were inversely associated with parental reports of their child’s appetite. Relatedly, elevated fasting ghrelin in underweight children ages 3 months to 7 years diagnosed with failure to thrive, suggests that ghrelin resistance could contribute to avoidant/restrictive eating (Pinsker et al., 2011). To understand whether ghrelin resistance contributes to dietary restriction in ARFID, it is important to explore whether ghrelin levels are similarly elevated to those observed in AN.

PYY is a 36-amino-acid peptide primarily secreted by the L-cells of the distal gut after eating, and induces satiation (Perry and Wang, 2012; Tortorella et al., 2014). Peak PYY concentrations occur between 15 and 120 minutes postprandial, and levels are typically lowest before breakfast (Adrian et al., 1985; Sedlackova et al., 2012). Most (Misra et al., 2006; Schorr and Miller, 2017; Sedlackova et al., 2012), but not all (Germain et al., 2007; Stock et al., 2005; Tam et al., 2020) studies find that, compared to average weight individuals, adolescents and adults with AN have paradoxically high fasting (Misra et al., 2006; Nakahara et al., 2007; Westwater et al., 2020) and postprandial PYY levels (Nakahara et al., 2007; Sedlackova et al., 2012). Further, higher PYY concentrations in AN are associated with less self-reported hunger (Stock et al., 2005). PYY levels may remain high in adolescents and adults with AN even after weight recovery (Nakahara et al., 2007), identifying PYY as a hormone that may be important in the pathophysiology of chronic restriction. Moreover, high PYY levels may counteract the orexigenic effects of elevated ghrelin in AN (Misra et al., 2006). To date no studies have described PYY levels in ARFID.

Because AN and low-weight ARFID are undernourished, exploring hormone levels in these two disorders may help reveal whether alterations are common consequences of starvation or are differentially related to disorder-specific pathology. Adolescence and young adulthood are important times of rapid growth and development, and thus critical transitional periods in which to identify neurobiological substrates relevant to treatment and/or prevention of restrictive eating. We compared fasting and postprandial concentrations of total ghrelin and total PYY in adolescent/young adult females with low-weight ARFID, AN and atypical AN, and HC. We hypothesized that, similar to AN, fasting and postprandial ghrelin and PYY levels would be higher in low-weight females with ARFID compared to HC.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Sixty-two low-weight (≤90% of expected median body weight determined by 50th percentile BMI for age, bone age, or height percentile) females (ages 10–22) and 32 female healthy controls (HC; ages 10–22) were consecutively recruited for one or both of two NIMH-funded studies on the neurobiology of low-weight eating disorders and ARFID. For inclusion in the parent R01 studies, participants with AN needed to report being in treatment for disordered eating and/or reported engaging in one or more of the following behaviors at a frequency of greater than once per month: restrictive eating, binge eating, purging, or excessive exercise. Those with low-weight ARFID either needed to report being in treatment for an eating/feeding disorder or report engaging in restrictive eating more frequently than once per month to be included in the parent R01 studies. All participants in the current study were diagnosed with either DSM-5 ARFID (n=22), AN-restricting subtype (n=23), or atypical AN-primarily restricting (n=17). Those who reported binge eating and/or purging were not included in these analyses because there is evidence that the binge/purge subtype of AN may have distinct aberrant hormone levels compared to the primarily restricting subtype (Eddy et al., 2015). Diagnoses were conferred via the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime 2013 working draft (KSADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 2013) and confirmed via the Pica, ARFID, Rumination Disorder Interview (PARDI; Bryant-Waugh et al., 2019) for ARFID or via symptom counts from the Eating Disorder Examination version 17.0 (EDE; Fairburn, Cooper, & O’Connor, 2008) for AN and atypical AN. Percent of expected weight was determined by the growth charts available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and 20 was the reference age for any participant older than 20 years. Atypical AN was defined as BMI >18.5 if 18 years or older, or above the 10th percentile for age if less than 18 years (all were at <90% median BMI per inclusion criteria). Importantly, all participants in this study were classified as being at a low body weight according to inclusion criteria, but there are no empirically supported weight cut-offs clearly demarcating AN and atypical AN (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, as part of our team’s larger study on low-weight eating disorders, we categorized participants as AN and atypical AN based on the above cut-offs to explore relationships between body weight and neurobiological functioning in those with restrictive eating. Similarly, all participants diagnosed with ARFID were low-weight as determined by the described inclusion criteria for the study.

HC were included if: they were between the 25th −85th BMI percentiles for age, reported regular menses (if at least two years post-menarcheal), reported no history of pubertal delay (i.e., menarche at >16 years or thelarche at >13 years), engaged in less than 10 hours of exercise or 25 miles of running per week in the three months preceding the primary study visit (as excessive exercise has been associated with higher ghrelin; Ackerman et al., 2012), and had no lifetime history of any psychiatric disorder as determined by the KSADS-PL. Exclusion criteria for all participants included use of systemic hormones including hormonal contraception, pregnancy, breastfeeding within eight weeks of the primary study visit, a history of psychosis, active substance abuse, hematocrit < 30%, potassium level < 3 mmol/L, and history of GI tract surgery or other conditions that could lead to low weight or alterations in appetite-regulating hormones.

Written informed consent was obtained from participants ≥18 years and from parents of subjects <18 years old; assent was obtained from subjects <18 years old. All participants were seen at the Massachusetts General Hospital Clinical Research Center and the Athinoula A. Martinos Imaging Center. All study procedures were approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Clinical characteristics of some study subjects have been previously reported (Aulinas et al., 2020; Breithaupt et al., 2020; Bryant-Waugh et al., 2019; Kambanis et al., 2020; Mancuso et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Mancuso et al. 2020 reported AUC and fasting levels for ghrelin and PYY, but not for the same subset of participants. In contrast to the Mancuso paper which focused on comparisons between HC and AN binge/purge and restricting subtypes, the current manuscript includes atypical AN and ARFID. Importantly, the focus of the current manuscript is, for the first time, to examine fasting and postprandial levels of appetite regulating hormones ghrelin and PYY in ARFID in comparison to AN and HC.

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Screening visit.

To determine eligibility, participants completed: a detailed medical history, a physical examination including height and weight, a blood sample to rule out anemia and electrolyte imbalances, a urine pregnancy test, and the KSADS-PL. Height was measured on a wall-mounted stadiometer in triplicate and weight was taken in a gown and on an electronic scale.

2.2.2. Primary study visit.

The primary study visits occurred within 8 weeks of the screening visit. Participants provided an updated medical history and physical examination with a research nurse practitioner including height, weight, and Tanner staging.

Participants were asked to fast (with the exception of water intake) starting at 11:30 pm the night prior to their primary study visit (i.e., at least 8 hours prior to the fasting blood draw). Adherence with the fasting protocol was confirmed upon the participant’s arrival to the study visit. After medical history assessment and physical examination, fasting blood was drawn around 08:45AM by trained nursing staff (fasting sample: T0). Participants then consumed a 400–427 kcal mixed breakfast meal standardized for nutrient content (approximately 20% calories from protein, 20% from fat, and 60% from carbohydrates) at approximately 09:00AM. As may be expected, some participants with ARFID reported eating a very limited range of foods (Thomas & Eddy 2019). For these participants, bionutritionists with the Translational and Clinical Research Centers at the Massachusetts General Hospital worked with participants to create a breakfast meal that matched our standard meal options for total caloric and macronutrient content, but consisted of the participant’s preferred/safe foods. Participants were asked to eat the entire meal over 15 minutes. Bionutrition staff weighed the meal upon completion to determine caloric intake. Blood was drawn serially for hormones postprandially at 30 (T30), 60 (T60), and 120 (T120) minutes post start of the standardized breakfast meal. Plasma samples were immediately placed on ice following venipuncture and spun in a refrigerated centrifuge. Serum samples were allowed to clot for 20 minutes and then spun in a refrigerated centrifuge; all samples were stored at −80 degrees Celsius until analysis. Participants completed the PARDI or EDE after other study components were completed.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. KSADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 2013).

The KSADS-PL is a semi-structured interview with good inter-rater reliability used to assess current and lifetime psychiatric history of children and young adults. Supplemental questions were developed by the study team and added to evaluate DSM-5 ARFID. Percent agreement on KSADS-PL diagnostic categories between two coders in a subset of this sample ranged from 94% (mood disorders) to 96% (anxiety disorders) and 100% (all other disorders; Kambanis et al., 2019).

2.3.2. PARDI (Bryant-Waugh et al., 2019).

The PARDI is a semi-structured multi-informant clinical assessment designed to assess DSM-5 criteria for pica, ARFID, and rumination disorders. Inter-rater reliability for a subset of the ARFID sample was acceptable (κ=.75) (Bryant-Waugh et al., 2019).

2.3.3. EDE (Fairburn et al., 2008).

The EDE is a well-validated interview assessing severity of eating disorder psychopathology, binge eating, purging, and other compensatory activities such as excessive exercise. The EDE was used to confer diagnosis of the restricting presentation of AN/atypical AN. Participants were excluded in the current analyses if they reported binge eating and/or purging an average of 3 or more times per month for the past 3 months. Inter-rater reliability for a random subset of the AN/atypical AN sample was excellent (κ = 1.0; Wang et al., 2019).

2.4. Biochemical Analysis

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used to assess plasma total ghrelin (EMD Millipore: Burlington, MA; intra-assay CV 1.32% and inter-assay CV 6.62%; lower limit of detection 50.0 pg/ml) and serum PYY levels (EMD Millipore; intra-assay CV 17–18% and inter-assay CV 12–18%; lower limit of detection 10.0 pg/mL).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

We used R for statistical analyses (R Core Team, 2018). We first compared clinical characteristics between groups using ANOVA and Chi-square tests. Hormone levels were not normally distributed and were, therefore, log-transformed before analyses. We examined data for outliers by determining if any values fell outside of three standard deviations beyond the mean for each time point (i.e., T0, T30, T60, T120) by group. No outliers were evident, and no data points appeared, via visual inspection of distribution plots, to be heavily influencing the mean of any group. For both ghrelin and PYY we calculated area under the curve (AUC: a measure of total exposure to ghrelin and PYY levels over the pre- and post-meal time points sampled), the nadir (for ghrelin) or peak (for PYY), as well as the percent change from fasting levels to the nadir or peak values. The formula for AUC is as follows: (((T0 hormone levels + T30 hormone levels)*30 minutes)/2) + (((T30 hormone levels + T60 hormone levels)*30 minutes)/2) + (((T60 hormone levels + T120 hormone levels)*60 minutes)/2).

For our main analyses, we ran ten statistical tests and applied the Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons across statistical models. We grouped our primary analyses into three clusters of tests: Fasting one-way ANOVAS; postprandial mixed ANOVAS; and summary ANOVAs. We first ran two between-subject ANOVAs to compare fasting levels in ghrelin and PYY using the significance threshold of p=.025 (p=.05/2 omnibus tests). Next, we conducted two mixed ANOVAs (separate analyses for ghrelin and PYY) to determine whether within-group differences existed between each time point post-meal (T30; T60; and T120) and fasting hormone levels (T0) as well as to compare hormone levels between groups using a significance threshold of p=.025 (p=.05/2 omnibus tests). We ran six separate between-group ANOVAs with a significance threshold of p=.0083 (p=.05/6 omnibus tests) for AUC, peak/nadir, and percent change from T0 to peak/nadir for ghrelin and PYY (i.e., we ran three ANOVAs for ghrelin with these outcomes and three for PYY) to more fully characterize the change in hormone levels around the standardized meal by group. We used Tukey’s correction for each set of planned post-hoc tests following the main analyses to account for multiple comparisons.

To explore the effect of age and pubertal status on primary fasting results, we conducted another four secondary between-subject ANCOVAs controlling for age and Tanner stage. Age and Tanner stage were included in separate models because they were highly correlated (rs= .792; p<.001).

We also conducted secondary analyses to determine if age, Tanner stage, or calories consumed during the breakfast meal accounted for our postprandial results. We chose to explore these covariates because descriptive analyses showed differences in these variables across groups (see Table 1). We chose age and Tanner stage as covariates rather than menstrual status because over half (57%) of the participants with ARFID had not yet begun menstruating but were also younger than 15 years of age. Thus, the menstrual status of the two eating disorder groups was not comparable as absence of periods before menarche is not equivalent to absence of periods from secondary amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, or delayed menarche, which were more likely in those with AN. In this situation, controlling for Tanner stage is more relevant than controlling for menstrual status. Importantly, for analyses comparing hormone levels among groups postprandially, participants who completed less than 50% of their meal were excluded from analysis because peripheral postprandial ghrelin (Le Roux et al., 2005) and PYY (Pedersen-Bjergaard et al., 1996) levels are impacted by preceding caloric consumption, and sufficient food needs to be consumed for observable changes in hormone levels preprandial to postprandial. Six ARFID (27.3%) and five AN (12.5%) were thus excluded from postprandial analyses. We did not choose a higher cut-off for meal completion because few ARFID participants ate 75% (n = 10) or 90% (n=5) of the meal. These numbers would have reduced our ability to explore postprandial results in those with ARFID. Because the ARFID and AN groups continued to differ for calories consumed even after excluding these participants, we also controlled for calories consumed in our analysis of postprandial measures. To explore the influence of these covariates, we conducted four secondary mixed ACNOVAs (comparing hormone levels over each timepoint both within and between subjects) and 12 between-subject ANCOVAs (for AUC, peak/nadir and percent change) controlling for age/Tanner stage and calories consumed. Age and Tanner stage were also highly correlated in the sample of those with postprandial hormone levels (rs=.838; p<.001), thus, calories consumed was included with either age or Tanner stage in separate analyses. For all secondary analyses, we used a significance threshold of p=.05.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Group | p Values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| ARFID (N = 22) | AN (N = 40) | HC (N = 32) | ARFID vs AN | ARFID vs HC | AN vs HC | |

|

| ||||||

| Age, Mean (S.D.) (years) | 14.4 (3.2) | 18.9 (3.1) | 17.4 (3.1) | <.001 | .003 | .126 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI z-score, Mean (S.D.) | −1.8 (0.81) | −1.7 (1.0) | .14 (0.50) | 1.00 | .001 | .001 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI Percentile, Mean (S.D.) | 6.7 (5.5) | 12.9 (11.8) | 55.2 (17.7) | .45 | .001 | .001 |

|

| ||||||

| Breast Tanner Stage, Mean (S.D.) | 3.1 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.1) | 4.4 (1.1) | .005 | .005 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-Described Illness Duration in months, Mean (S.D.) | 11.4 (9.2) | 10.4 (9) | N/A | .73 | N/A | N/A |

|

| ||||||

| Calories Consumed During Meal, Mean (S.D.) | 275.4 (107.5) | 366.8 (85.9) | 378.3 (54.8) | .001 | .001 | 1.00 |

|

| ||||||

| Calories Consumed During Meal (only those that ate at least 50%), Mean (S.D.) | 329.6 (63.1) | 394.9 (42.9) | 378.3 (54.8) | <.001 | .012 | .664 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of participants with comorbid diagnoses (%) | .058 | N/A | N/A | |||

| Mood Disorders | 1 (4.5) | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| Anxiety Disorders | 7 (31.8) | 27 (67.5) | 0 (0) | |||

| PTSD | 0 (0) | 2.5 (1) | 0 (0) | |||

| ADHD | 3 (13.6) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Number of participants on psychoactive medications (%) | 11 (50) | 24 (60) | 0 (0) | .45 | N/A | N/A |

| Antidepressants | 4 (18.2) | 16 (40) | 0 (00 | .15 | N/A | N/A |

| Antipsychotics | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Anxiolytics | 4 (18.2) | 8 (20) | 0 (0) | .87 | N/A | N/A |

| Stimulants | 2 (9.1) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | .30 | N/A | N/A |

Note. ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; AN = anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa primarily restricting presentation; HC = healthy controls; BMI = Body Mass Index; S.D. = standard deviation; Mean Calories Consumed During the Meal is calculated for everyone in the sample, even those that ate less than 50% of the meal; N/A: not applicable because exclusionary criteria for HC included (i) having a history of or current eating disorder, (ii) having a current psychiatric disorder, and (iii) taking psychoactive medications; PTSD = Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; significant p values at <.05 for group mean comparisons are indicated in bold.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Most of the sample identified as Caucasian (83%; n=78) and non-Hispanic (91.7%; n=86). Those diagnosed with atypical AN did not differ in ghrelin or PYY concentrations (ps>.349), global EDE scores (p=.962), amount consumed during the breakfast meal (p=.251), age (p=.069), or Tanner stage breast (p=.149) from those with AN (see supplemental table S1). Given that the differences in weight between AN and low-weight atypical AN were not associated with variables of interest in this study, these two groups were combined as an overall AN group comparable to the ARFID group for weight. The ARFID group (mean age=14.4±3.2) differed from the AN group (mean age=18.9±3.1) and HC (mean age=17.4 ±3.1) in age, Tanner stage, and calories consumed during the breakfast meal (ps≤.012, see Table 1). This is consistent with the lower age of onset seen across ARFID samples compared to individuals with AN (Becker et al., 2019; Nicely et al., 2014).

ARFID and AN groups did not differ in the presence of psychological comorbidities or reported use of psychiatric medications.

3.2. Main Analyses:

3.2.1. Mean comparisons of fasting ghrelin and PYY levels in ARFID, AN, and HC.

These analyses (see Table 2) included all participants who provided fasting blood samples for ghrelin (ARFID=22; AN=40; HC=32) or PYY (ARFID=21; AN=40; HC=30). Counter to expectations, individuals with ARFID had lower fasting ghrelin than those with AN (p=.003) but did not differ from HC (p=.62). AN had higher fasting ghrelin than HC (p=.008), replicating previous findings. When age or Tanner stage were included as covariates, ghrelin comparisons between ARFID and AN remained significant (p=.013 and p=.008 respectively) and ghrelin levels in AN remained significantly elevated compared to HC (ps≤.014; see supplemental tables S2 and S3).

Table 2.

Mean comparisons of fasting total ghrelin and PYY levels in individuals with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), anorexia nervosa (AN), and healthy controls (HC)

| Mean ± (S.D./S.E.M.) | ANOVA Results | p Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cohen’s d) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| F (df1, df2) | Omnibus p (η2) | ARFID vs AN | ARFID vs. HC | AN vs HC | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| T0 Total Ghrelin (pg/mL) | ARFID (n = 22) | AN (n = 40) | HC (n = 32) | |||||

| 700.2 (168.97/56.8) | 835.45 (194.50/34.8) | 683.4 (270.61/47.8) | 7.71 (2, 80) | <.001 (.16) | .003 (1.26) | .62 (.25) | .008 (.74) | |

| T0 PYY (pg/mL) | ARFID (n = 21) | AN (n = 40) | HC (n = 32) | |||||

| 98.4 (42.28/8.2) | 113.2 (30.30/6.9) | 80.1 (32.99/6.0) | 6.78 (2, 78) | .002 (.15) | .511 (.35) | .155 (.56) | .001 (.90) | |

Note. ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; AN = anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa primarily restricting presentation; HC = healthy controls; S.D.= standard deviation; S.E.M= standard error of the mean; T0 = hormone levels after an 8+ hour overnight fast; significant p values at <.025 for the omnibus ANOVA and <.05 for group mean post-hoc comparisons are indicated in bold.

Similarly, and contrary to expectations, PYY levels did not differ between ARFID and HC, or between ARFID and AN. Inclusion of covariates did not change these results. However, those with AN had higher PYY than HC (p=.001). Including age or Tanner stage in models did not change the pattern of results or comparisons in PYY levels between AN and HC (ps≤.003; see supplemental tables S2 and S3).

3.2.2. Postprandial ghrelin and PYY patterns in ARFID, AN, and HC following the standard meal.

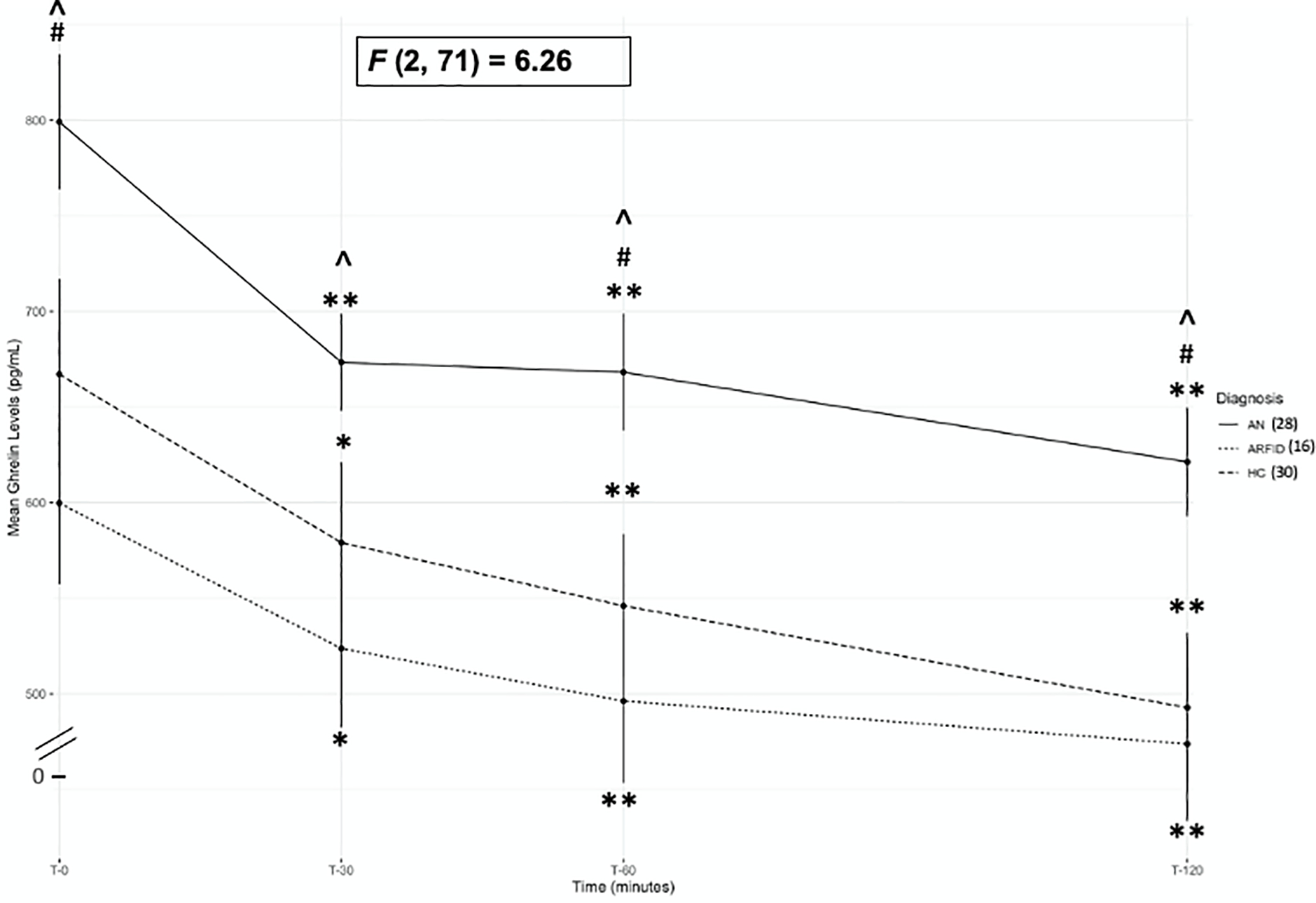

Total ghrelin levels at each postprandial timepoint (i.e., T30, T60, and T120 minutes post the standardized breakfast) were significantly lower compared to fasting ghrelin levels in all groups [ARFID (n=16), AN (n=28), and HC (n=30); ps≤.013; see Table 3; Figure 1] and nadir levels occurred most often at T120 in all groups (51% for ARFID; 57.1% for AN, 63.3% for HC).1

Table 3:

Mean comparisons of total ghrelin levels around a standardized meal (at T0, T30, T60, T120) between individuals with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), anorexia nervosa (AN), and healthy controls (HC)

|

Mixed ANOVA

| |||||||||

| Time | F(3, 213) = 51.01 | p < .001, η2 = .076 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mean ± (S.D./S.E.M.) | p Values (Cohen’s d) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | Timepoint | T0 vs. T30 | T0 vs. T60 | T0 vs. T120 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| T0 | T30 | T60 | T120 | ||||||

| ARFID (n = 16) | 599.7 (168.96/42.2) | 523 (164.29/41.1) | 496.2 (170.60/42.7) | 473.7 (160.20/40.1) | .013 (1.46) | <.001 (1.03) | < .001 (1.40) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| AN (n = 28) | 799.1 (185.71/35.1) | 673.3 (133.08/25.2) | 668.2 (160.49//30.3) | 621.2 (149.01/28.2) | <.001 (1.10) | <.001 (.80) | <.001 (1.19) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| HC (n = 30) | 667.1 (271.80/49.6) | 579.0 (229.51/41.9) | 546.0 (204.39/37.3) | 492.8 (213.58/39.0) | .006 (.81) | <.001 (1.06) | <.001 (1.38) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| All groups (n = 74) | 702.56 (233.20/27.11) | 602.76 (191.14/22.22) | 581.48 (192.61/22.39) | 537.25 (189.77/22.06) | < .001 (1.01) | < .001 (0.95) | < .001 (1.31) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | F (2,71) = 6.26 | p = .003, η 2 = .135 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mean ± (S.D./S.E.M.) | p Values (Cohen’s d) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total Ghrelin (pg/mL) | Group | ARFI D vs AN | ARFI D vs HC | AN vs HC | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ARFID (n = 16) | AN (n = 28) | HC (n = 30) | |||||||

| T0 | 599.7 (168.96/42.2) | 799.1 (185.71/35.1) | 667.1 (271.80/49.6) | .015 (1.10) | .787 (.182) | .028 (.681) | |||

| T30 | 523.7 (164.08/41.1) | 673.3 (229.51/25.2) | 579.0 (229.51/41.9) | .006 (1.06) | .739 (.208) | .062 (.644) | |||

| T60 | 496.2 (170.60/42.7) | 668.2 (160.49/30.3) | 546.0 (204.39/37.3) | .006 (1.13) | .650 (.249) | .022 (.776) | |||

| T120 | 473.7 (149.01/40.1) | 621.2 (149.01/28.2) | 492.8 (213.58/39.0) | .014 (1.05) | .998 (.013) | .003 (.823) | |||

|

|

|||||||||

| One-Way ANOVAs | F(df1, df2) | Omnibus p (η2) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| AUC | 61249.2 (18832.12/4708.0) | 80892.5 (15602.96/2948.7) | 61249.2 (18832.12/4708.0) | 6.44 (2,71) | .003 (.154) | .007 (1.180) | .77 (.184) | .012 (.793) | |

| Nadir | 453.0 (153.72/38.4) | 585.7 (109.26/20.6) | 453.0 (153.72/38.4) | 5.89 (2,71) | .004 (.144) | .026 (1.10) | 1.000 (.042) | .008 (.820) | |

| Percent change from T0 to nadir | −24.9(11.11/2.8) | −25.2(12.26/2.1) | −24.9(11.11/2.8) | 1.10 (2,71) | .338 (.030) | ||||

Note: ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; AN = anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa primarily restricting presentation; HC = healthy controls; S.D. = standard deviation; S.E.M = standard error of the mean; only participants who ate at least 50% (i.e., 210 Kcal) of the standardized breakfast meal are included in comparisons; T0 = hormone levels following a 8+ hour overnight fast, T30 = hormone levels 30 minutes post breakfast meal; T60 = 60 minutes post breakfast meal; T120 = 120 minutes post breakfast meal; AUC = area under the curve; significant p values at <.025 for the omnibus mixed ANOVA, <.0083 for the one-way omnibus ANOVAs, and <.05 for group mean post-hoc comparisons are indicated in bold.

Figure 1.

Mean ghrelin levels at T0, T30, T60, and T120 timepoints for anorexia nervosa/atypical anorexia nervosa-restricting (AN), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and healthy controls (HC)

Note. ^= p<.05 comparison between ARFID and AN; #= p<.05 comparison between AN and HC; ** = p< .002 and *=p<.05 within group comparison between each post-prandial timepoint (T30, T60 and T120) and fasting (T0). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. F value represents between group comparisons (between AN, ARFID, and HC).

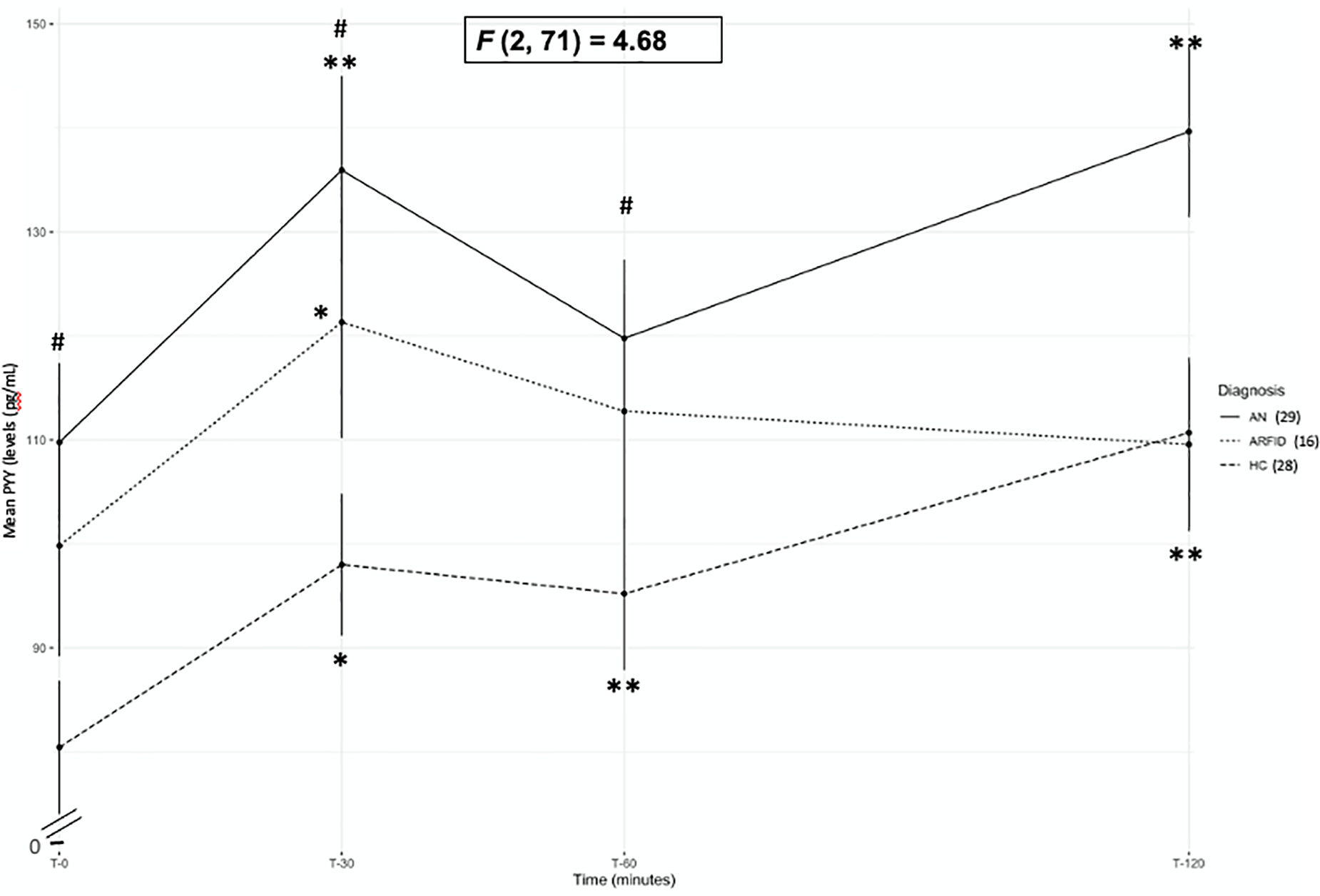

In ARFID (n=16), PYY levels were increased only at T30 compared to fasting PYY (p=.005; see Table 4; Figure 2). However, PYY in AN (n=29) was increased at T30 and T120 timepoints compared to fasting levels (ps≤.001; see Table 4; Figure 2) and was increased at all time points compared to fasting levels in HC (ps≤.006; see Table 4; Figure 2). Thus, the difference in PYY post-meal was not sustained in ARFID, unlike in AN and HC. To explore the postprandial PYY pattern in ARFID more closely, we conducted secondary t-tests comparing the timing of peak PYY levels in ARFID to AN and HC. Peak PYY values occurred at T30 for a majority (56.3%) of ARFID participants, in comparison to less than half of AN (41.4%) and HC (25%). This was a significant difference between ARFID and HC (p=.037). When covariates (age/tanner stage and calories consumed) were included in the mixed models, the effect of time (e.g., within group differences between T0 and all other time points) were no longer significant because changes in ghrelin and PYY are directly consequent to calories consumed (see supplemental tables S4–S7).

Table 4.

Mean comparisons of total PYY levels around a standardized meal (at T0, T30, T60, T120) between individuals with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), anorexia nervosa (AN), and healthy controls (HC)

|

Mixed ANOVA

| |||||||||

| Time | F (3, 210) = 51.0 | p < .001, η2 = .058 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mean ± (S.D./S.E.M.) | p Values (Cohen’s d) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | Timepoint | T0 vs. T30 | T0 vs. T60 | T0 vs. T120 | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| T0 | T30 | T60 | T120 | ||||||

| ARFID (n = 16) | 99.8 (42.27/10.6) | 121.3 (121.31/11.1) | 112.8 (45.28/11.3) | 109.6 (33.18/8.3) | .005 (.536) | .290 (.251) | .178 (.355) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| AN (n = 29) | 109.76 (40.77/7.6) | 135.9 (135.93/9.0) | 119.8 (40.92/7.5) | 139.7 (4.17/8.2) | <.001 (.576) | .108 (.260) | <.001 (.691) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| HC (n = 28) | 80.4 (33.63/6.4) | 98.0 (98.00/6.8) | 95.2 (38.73/7.3) | 110.7 (34.06/6.4) | .006 (.513) | <.001 (.260) | <.001 (.691) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| All groups (n = 74) | 96.33 (40.21/4.71) | 118.18 (45.81/5.36) | 108.81 (41.83/4.90) | 121.95 (40.41/5.36) | <.001 (.515) | <.001 (.306) | <.001 (.663) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Group | F (2, 71) = 4.68 | p = .012, η2 = .102 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mean ± (S.D./S.E.M) | p Values (Cohen’s d) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total PYY (pg/mL) | Group | AR FID vs AN | ARFI D vs HC | AN vs HC | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| ARFID (n = 16) | AN (n = 29) | HC (n = 28) | |||||||

| T0 | 99.8 (42.27/10.6) | 109.76 (40.77/7.6) | 80.4 (33.63/6.4) | .715 (.237) | .127 (.552) | .005 (.769) | |||

| T30 | 121.3 (121.31/11.1) | 135.9 (135.93/9.0) | 98.0 (98.00/6.8) | .600 (.311) | .173 (.569) | .004 (.884) | |||

| T60 | 112.8 (45.28/11.3) | 119.8 (40.92/7.5) | 95.2 (38.73/7.3) | .741 (.224) | .353 (.646) | .037 (.382) | |||

| T120 | 109.6 (33.18/8.3) | 139.7 (4.17/8.2) | 110.7 (34.06/6.4) | .127 (.722) | 1.00 (.695) | .065 (.012) | |||

|

| |||||||||

| One-Way ANOVAs | F (df1, df2) | Omnibus p(η2) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| AUC | 13497.2(4598.53/1149.6) | 15303.1 (4840.82/898.9) | 11751.4 (4003.46/756.6) | 4.25 (2,70) | .018 (.108) | ||||

| Peak | 130.4 (43.72/10.9) | 151.1 (48.60/9.0) | 117.5 (37.22/7.0) | 3.71 (2,70) | .029 (.100) | ||||

| Percent change from T0 to peak | 36.5 (34.79/8.7) | 45.1 (36.79/6.8) | 58.1 (46.26/8.7) | 1.09 (2,70) | .341 (.030) | ||||

Note: ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; AN = anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa primarily restricting presentation; HC = healthy controls; S.D.= standard deviation; S.E.M = standard error of the mean; only participants who ate at least 50% (i.e., 210 Kcal) of the standardized breakfast meal are included in comparisons; T0 = hormone levels following a 8+ hour overnight fast, T30 = hormone levels 30 minutes post breakfast meal; T60 = 60 minutes post breakfast meal; T120 = 120 minutes post breakfast meal; AUC = area under the curve; significant p values <.025 for the omnibus mixed ANOVA, <.0083 for the one-way omnibus ANOVAs, and <.05 for group mean post-hoc comparisons are indicated in bold.

Figure 2.

Mean PYY levels at T0, T30, T60, and T120 timepoints for anorexia nervosa/atypical anorexia-restricting (AN), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and healthy controls (HC)

Note. #=p<.05 comparison between AN and HC; **=p<.002 and *=p<.05 within group comparison between each post-prandial timepoint (T30, T60 and T120) and fasting (T0). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. F value represents between group comparisons (between AN, ARFID, and HC).

3.3.3. Mean comparisons of ghrelin and PYY levels in ARFID, AN, and HC around a standardized meal.

Those with ARFID (n=16) had lower ghrelin at each timepoint (T0, T30, T60, and T120), and lower area under the curve (AUC), and nadir levels compared to those with AN (n=28; ps≤.026; see Table 3 and Figure 1). When age and calories consumed or Tanner stage and calories consumed were included as covariates, comparisons between ARFID and AN remained significant at T30, T60, T120, AUC and nadir levels (ps≤.049; see supplemental tables S4 and S5). There were no differences in ghrelin between ARFID (n=16) and HC (n=30). Those with AN had higher ghrelin at T0, T60, and T120 as well as higher ghrelin AUC and nadir levels compared to HC (ps≤.028; see Table 3 and Figure 1). These comparisons between AN and HC remained significant when either age and calories consumed or Tanner stage and calories consumed were included as a covariates (ps≤.039; see supplemental tables S4 and S5). There were no between-group differences in the percent change from fasting to nadir ghrelin levels.

ARFID (n=16) did not differ from either AN (n=29) or HC (n=28) for PYY concentrations at any timepoint, PYY AUC, peak PYY, or percent change from fasting to peak PYY concentrations (see Table 4; Figure 2) and this pattern did not change when either age and calories consumed, or Tanner stage and calories consumed were entered as covariates (see supplemental tables S6 and S7). However, compared to HC, those with AN had higher PYY at T0, T30, T60 (ps≤. 037; See Table 4; Figure 2). PYY at T120, PYY AUC, Peak PYY, and percent change from fasting to peak PYY concentrations did not differ between AN and HC. When age and calories consumed were included as covariates, PYY levels at T0 and T30 remained significantly higher in those with AN compared to HC (ps≤. 011; see supplemental table S6). When Tanner stage and calories consumed were included as covariates, PYY at T0, T30, and T60 remained significantly higher in those with AN compared to HC (ps≤. 049; see supplemental table S7).

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report fasting and postprandial levels of ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone, and PYY, an anorexigenic hormone, in low-weight young females with ARFID compared to those with restricting AN/atypical AN and HC. Studies have consistently reported higher ghrelin and PYY concentrations in individuals with AN compared to HC (Nakahara et al., 2007; Schorr and Miller, 2017; Singhal and Misra, 2014; Tortorella et al., 2014). We hypothesized that elevated gastrointestinal-derived appetite-regulating hormone levels would be common to low-weight eating disorders in general, and that similar to AN, individuals with ARFID would have higher ghrelin and PYY levels than HC. Contrary to our expectations, low-weight adolescent/young adult females with ARFID had lower fasting and postprandial ghrelin levels than those with AN and similar levels of ghrelin to HC. The pattern of decreased ghrelin levels (compared to fasting levels) at all timepoints following a meal was consistent across all groups. Those with ARFID did not differ in fasting or postprandial PYY levels from those with AN or HC. The expected pattern of sustained higher PYY postprandially compared to fasting levels was evident only for those with AN and HC. In those with ARFID, only PYY at T30 was increased compared to fasting.

Despite being similarly low-weight, adolescents with ARFID had lower fasting, postprandial, nadir, and AUC ghrelin levels than those with AN. While those with ARFID ate less during the breakfast meal, were younger, and were at a lower pubertal stage than those with AN, secondary analyses controlling for age or Tanner stage and calories consumed showed the same significant differences in ghrelin at every timepoint, ghrelin AUC, and nadir ghrelin levels. Thus, ghrelin levels in low-weight ARFID seem distinct from those in AN, perhaps consequent to underlying disorder-specific psychopathology. More specifically, a lack of interest in eating or food is one of the three primary presentations of ARFID (APA, 2013), which can often result in low weight (Thomas and Eddy, 2019). It may be that the relatively low levels of ghrelin observed in our ARFID sample in the context of low weight contribute to the low drive to eat in this presentation of ARFID. Consistent with this hypothesis, a higher percentage of females with ARFID (27.3%) in our sample consumed less than 50% of the standardized breakfast meal compared to those with AN (12.5%). Even within the subsample that ate at least half the meal, those with ARFID ate significantly less than those with AN or HC.

Importantly, the differences in age and developmental stage observed between our AN and ARFID samples reflect differences in illness course that are specific to these diagnoses. Individuals with low-weight ARFID tend to present in childhood or early adolescence due to a younger age of onset (often in infancy or early toddlerhood; Sharp et al., 2016). In contrast, AN has a peak onset in late adolescence and early adulthood (Hudson et al., 2007). Therefore, while we were not able to match groups based on age or Tanner stage, the clinical presentation of these participants appears commensurate with their typical clinical presentations. It may be that these differences in presentation also help explain the distinct ghrelin response we observed between those with low-weight ARFID and AN. While elevated ghrelin levels have been found following weight loss (Kelishadi et al., 2008) as seen in AN, it is unclear how longstanding low-weight status during early childhood may affect ghrelin functioning.

Overall these results may suggest that relatively low ghrelin levels for weight represent a possible biomarker distinguishing ARFID from AN, which may be relevant for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning for low-weight female adolescents/young adults. Younger adolescents, in particular, have difficulty reporting on cognitive eating disorder symptoms APA, 2013; Mairs & Nicholls, 2016) that are critical for a differential diagnosis between AN and ARFID. Thus, methods that are not reliant on selfreport could improve diagnostic accuracy. However, studies comparing those with AN to constitutionally lean individuals also report low levels of ghrelin in the context of low-weight status (Germain et al., 2009, 2007; Tolle et al., 2003).Therefore, in order to determine the relevance of ghrelin levels as a biomarker for ARFID, future research should explore how low-weight ARFID compares to both AN and constitutionally thin individuals.

Our ghrelin findings may also offer novel psychopharmacologic treatment targets for individuals with low-weight ARFID, even though there were no differences in ghrelin levels between those with ARFID and HC. In AN ghrelin levels are elevated compared to HC and it is generally thought that this is an adaptive response to promote food intake in an undernourished state (Misra et al., 2005), suggesting that lower ghrelin levels are problematic in the context of low weight. There are currently no empirically-supported treatments for ARFID and, while some studies show promising pilot findings (Brigham et al., 2018; Bryson et al., 2018; Thomas and Eddy, 2019), further therapeutic strategies are needed, especially for individuals who are underweight because complications of chronic starvation can seriously disrupt development (Singhal and Misra, 2014). In individuals with AN, exogenous intravenous ghrelin administration shows mixed findings. One study reported little benefit of intravenous ghrelin administration (Miljic et al., 2006) in increasing caloric intake, perhaps related to the already high levels of ghrelin in those with AN, while another described increased caloric intake when ghrelin is administered twice daily in a weight-based dose (Schalla and Stengel, 2018). There is also early evidence that a ghrelin agonist, relamorelin, leads to a trend in weight gain after 4 weeks in adults with AN; notably, some individuals with AN did not complete treatment in this study due to increased hunger (Fazeli et al., 2018). Because ghrelin levels may be inappropriately low in those with low-weight ARFID and ARFID is not characterized by weight and shape concerns, administration of a ghrelin analog could be an acceptable treatment for ARFID, particularly for those patients with ARFID who need to gain weight despite having little or no interest in eating. Without a desire to control appetite to maintain restrictive eating (and low weight), individuals with low-weight ARFID may better tolerate increased hunger to support needed weight gain/regain.

Our results with PYY replicate previous findings in that PYY concentrations were elevated in those with AN compared to HC (Prince et al., 2009; Schorr and Miller, 2017; Singhal and Misra, 2014). However, PYY concentrations for those with ARFID did not differ at any timepoint from either those with AN or HC. In a starved state, such as low-weight ARFID or AN, PYY levels that are lower than in HC would represent an adaptive hormonal response to encourage increased caloric intake (Singhal and Misra, 2014). Thus, PYY levels that are high (as seen in AN) or similar to levels in HC (as seen in our low-weight ARFID sample) are maladaptively high for a satiety-inducing hormone, possibly hindering appropriate food intake. In addition, secondary analyses suggest that more than half of the ARFID sample had earlier peak PYY levels at 30 minutes post-meal which was significantly higher than the percentage of HC who experienced peak PYY values 30 minutes post-meal. Studies have found that PYY is related to self-reported feelings of fullness (Costabile et al., 2018) in healthy individuals and those with eating pathology (Keel et al., 2018). An early peak in PYY concentrations following food intake may underlie symptom reports from those with ARFID who describe difficulty finishing meals due to feeling full quickly after starting to eat (Thomas and Eddy, 2019). Results lend further support to findings suggesting that PYY is involved in the pathophysiology of low-weight eating disorders and suggest that elevated PYY levels in the context of low weight may be an important diagnostic marker of AN when considering a diagnosis of AN versus low-weight ARFID.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. First, our study sample is small, especially for those with ARFID who completed at least 50% of the standardized meal. In addition, our ARFID group was younger than either those with AN or HC. We, therefore, conducted secondary analyses to explore if age, Tanner staging, or calories consumed altered our findings. The pattern of significant differences between groups was largely consistent despite the separate inclusion of these covariates in group comparisons, increasing confidence in our findings. Nevertheless, these results need to be replicated in larger samples and with age-matched samples. Our sample also comprised adolescent/young-adult females who were predominantly Caucasian and non-Hispanic. Future research is needed to determine generalizability to older individuals with ARFID, males, and across racial and ethnic groups. ARFID is a heterogeneous diagnosis, with individuals meeting diagnostic criteria across the age and weight spectrums and with complex presentations. While all participants with ARFID in this study presented with some degree of lack of interest in eating as evident by their low-weight status, difficulty finishing the standardized meal, and reports of low hunger during interview assessments, we do not have information on the degree to which all participants may have experienced sensory sensitivities to foods and/or a fear of aversive consequences to eating (e.g., vomiting, choking, GI pain, allergic reactions). Future research should explore associations between appetite-regulating hormones and specific ARFID symptoms and presentation types. Importantly, for this study we measured total levels of ghrelin and PYY, which include forms that are active and inactive in appetite regulation. Consistent with literature comparing active forms and total levels of ghrelin and PYY between AN and HC, our results show higher total fasting and postprandial ghrelin and PYY in those with AN (Nakahara et al., 2007; Schorr and Miller, 2017; Singhal and Misra, 2014). Of note, our team’s previously published data show that decreases in postprandial levels of total ghrelin and increases in postprandial levels of total PYY are positively associated with reductions in visual analogue scale scores for prospective food consumption (Mancuso et al., 2020), consistent with the established appetite-regulating effects of these hormones. Future studies should specifically explore the impact of acylated and desacylated forms of ghrelin on comparisons between ARFID, AN, and HC. Finally, this study has a cross-sectional design; therefore, we cannot infer causality from our data. Future larger longitudinal studies should explore hormone changes across key developmental periods and hormone levels before and after treatment to further establish the link between appetite-regulating hormones and eating behavior in ARFID.

Important strengths to highlight in this study include that this study is the first to report on appetite-regulating hormones responsive to gastrointestinal nutrients around a standardized meal in ARFID. Diagnoses were assigned via structured clinical interviews and we compared ghrelin and PYY between ARFID and AN in addition to comparisons with HC. Participants with ARFID or AN were similarly low-weight and explored for the possible effects of age, developmental stage, and calories consumed in secondary analyses.

In conclusion, concentrations of ghrelin and PYY may be important in differentiating low-weight ARFID and AN and may provide useful psychopharmacologic treatment targets for low-weight ARFID. Findings are particularly relevant for adolescents with low-weight eating disorders, because reduced risk of long-term health consequences depend on accurate diagnosis and effective treatment during this critical developmental period.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Low-weight ARFID females are as undernourished as those with anorexia nervosa (AN)

Low-weight ARFID showed lower levels of total ghrelin around a meal than AN

Low-weight ARFID did not differ from AN or healthy controls (HC) in PYY levels

Low-weight ARFID did not show sustained high PYY levels post-meal

Hormone differences may differentiate low-weight ARFID and AN

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health: NIMH (KRB, F32MH111127), (KTE, MM, EAL, R01MH103402), (JJT, EAL, NM, R01MH108595), (LB, T32MH112485) and (EAL, K24MH120568) as well as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Disease (EAL, P30 DK040561). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest/disclosure:

Dr. Micali receives honoraria from the Gertrude von Meissner foundation, for a scientific advisory committee role. Dr. Thomas reports honoraria from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. for service as an associate editor for the International Journal of Eating Disorder, and from the Academy of Eating Disorders for serving on the Board of Directors. Dr. Thomas also receives royalties from Harvard Health Publications and Hazelden for the sale of her book, Almost Anorexic: Is My (or My Loved One’s) Relationship with Food a Problem? Drs. Thomas and Eddy receive royalties from Cambridge University Press for the sale of their book, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Drs. Thomas, Eddy and Becker receive royalties from Cambridge University Press for their upcoming self-help book for adults with ARFID. Dr. Misra has received honoraria from the American Board of Pediatrics and royalties from UpToDate and is a consultant for Sanofi and Abbvie. Dr. Lawson is on the scientific advisory board and has a financial interest in OXT Therapeutics, a company developing an intranasal oxytocin and long-acting analogs of oxytocin to treat obesity and metabolic disease. She also receives royalties from UptoDate. Christopher Mancuso, Elisa Asanza, Lauren Breithaupt, Melissa J. Dreier, Meghan Slattery, and Franziska Plessow do not have any disclosures to report. The interests of all authors were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare as well as Geneva University Hospital and the University of Geneva in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Footnotes

Only participants who contributed data values at all time points post-meal (T30, T60, T120) were included in postprandial analyses. Participants were excluded from post-meal analyses if they failed to eat the meal or eat at least 50% of the meal, were too anxious about blood draws to provide more than a fasting sample, postprandial blood from one or more of the post-meal time points was not collected due to study complications during the primary study visit, or their samples were determined insufficient for analysis by the lab.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ackerman KE, Slusarz K, Guereca G, Pierce L, Slattery M, Mendes N, Herzog DB, Misra M, 2012. Higher ghrelin and lower leptin secretion are associated with lower LH secretion in young amenorrheic athletes compared with eumenorrheic athletes and controls. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab 302, 800–806. 10.1152/ajpendo.00598.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian TE, Ferri GL, Bacarese-Hamilton AJ, Fuessl HS, Polak JM, Bloom SR, 1985. Human distribution and release of a putative new gut hormone, peptide YY. Gastroenterology 89, 1070–1077. 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90211-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed, American Psychiatric. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aulinas A, Marengi DA, Galbiati F, Asanza E, Slattery M, Mancuso CJ, Wons O, Micali N, Bern E, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, Misra M, Lawson EA, 2020. Medical comorbidities and endocrine dysfunction in low-weight females with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder compared to anorexia nervosa and healthy controls. Int. J. Eat. Disord 1–6. 10.1002/eat.23261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KR, Keshishian AC, Liebman RE, Coniglio KA, Wang SB, Franko DL, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, 2019. Impact of expanded diagnostic criteria for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder on clinical comparisons with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord 52, 230–238. 10.1002/eat.22988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breithaupt L, Chunga-Iturry N, Lyall AE, Cetin-Karayumak S, Becker KR, Thomas JJ, Slattery M, Makris N, Plessow F, Pasternak O, Holsen LM, Kubicki M, Misra M, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, 2020. Developmental stage-dependent relationships between ghrelin levels and hippocampal white matter connections in low-weight anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 119, 104722. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham KS, Manzo LD, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, 2018. Evaluation and Treatment of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) in Adolescents. Physiol. Behav 6, 107–113. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh R, Markham L, Kreipe RE, Walsh BT, 2010. Feeding and eating disorders in childhood. Int. J. Eat. Disord 43, 98–111. 10.1002/eat.20795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh R, Micali N, Cooke L, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, 2019. Development of the Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview, a multi-informant, semi-structured interview of feeding disorders across the lifespan: A pilot study for ages 10–22. Int. J. Eat. Disord 52, 378–387. 10.1002/eat.22958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson AE, Scipioni AM, Essayli JH, Mahoney JR, Ornstein RM, 2018. Outcomes of low-weight patients with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa at long-term follow-up after treatment in a partial hospitalization program for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord 51, 470–474. 10.1002/eat.22853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costabile G, Griffo E, Cipriano P, Vetrani C, Vitale M, Mamone G, Rivellese AA, Riccardi G, Giacco R, 2018. Subjective satiety and plasma PYY concentration after wholemeal pasta. Appetite 125, 172–181. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy KT, Lawson EA, Meade C, Meenaghan E, Horton SE, Misra M, Klibanski A, Miller KK, 2015. Appetite regulatory hormones in women with anorexia nervosa: Binge-eating/purging versus restricting type. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 19–24. 10.4088/JCP.13m08753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M, 2008. The Eating Disorder Examination, in: Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. Guildford Press, New York, NY, pp. 1–49. 10.1037/t03975-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli Pouneh K, Lawson EA, Faje Alexander T, Eddy KT, Lee H, Fiedorek FT, Breggia A, Gaal Ildiko M, DeSanti R, Klibanski A, 2018. Treatment With a Ghrelin Agonist in Outpatient Women with Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Clinical Trial 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain N, Galusca B, Grouselle D, Frere D, Tolle V, Zizzari P, Lang F, Epelbaum J, Estour B, 2009. Ghrelin/obestatin ratio in two populations with low bodyweight: Constitutional thinness and anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, 413–419. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain N, Galusca B, Le Roux CW, Bossu C, Ghatei MA, Lang F, Bloom SR, Estour B, 2007. Constitutional thinness and lean anorexia nervosa display opposite concentrations of peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide 1, ghrelin, and leptin. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 85, 967–971. 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Campos M, Aguilera CM, Cañete R, Gil A, 2006. Ghrelin: a hormone regulating food intake and energy homeostasis. Br. J. Nutr 96, 201–226. 10.1079/bjn20061787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsen LM, Lawson EA, Christensen K, Klibanski A, Goldstein JM, 2014. Abnormal relationships between the neural response to high- and low-calorie foods and endogenous acylated ghrelin in women with active and weight-recovered anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. - Neuroimaging 223, 94–103. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC, 2007. The Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 61, 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambanis PE, Kuhnle MC, Wons OB, Jo JH, Keshishian AC, Hauser K, Becker KR, Franko DL, Misra M, Micali N, Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ, 2020. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidities in children and adolescents with full and subthreshold avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord 53, 256–265. 10.1002/eat.23191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Perepletchikova F, Brent D, Ryan N, 2013. The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia: Working Draft. [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Eckel LA, Hildebrandt BA, Haedt-Matt AA, Appelbaum J, Jimerson DC, 2018. Disturbance of gut satiety peptide in purging disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord 51, 53–61. 10.1002/eat.22806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelishadi R, Hashemipour M, Mohammadifard N, Alikhassy H, Adeli K, 2008. Short- and long-term relationships of serum ghrelin with changes in body composition and the metabolic syndrome in prepubescent obese children following two different weight loss programmes. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 69, 721–729. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshaviah A, Edkins K, Hastings ER, Krishna M, Franko DL, Herzog DB, Thomas JJ, Murray HB, Eddy KT, 2014. Re-examining premature mortality in anorexia nervosa: A meta-analysis redux. Compr. Psychiatry 55, 1773–1784. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson EA, Eddy KT, Donoho D, Misra M, Miller KK, Lydecker JA, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, 2011. Appetite-regulating hormones cortisol and peptide YY are associated with disordered eating psychopathology, independent of body mass index. Eur. J. Endocrinol 164, 253–261. 10.1530/EJE-10-0523.Appetite-regulating [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux CW, Patterson M, Vincent RP, Hunt C, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, 2005. Postprandial plasma ghrelin is suppressed proportional to meal calorie content in normal-weight but not obese subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 90, 1068–1071. 10.1210/jc.2004-1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mairs R, Nicholls D, 2016. Assessment and treatment of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Arch. Dis. Child 101, 1168–1175. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammel KA, Ornstein RM, 2017. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: A new eating disorder diagnosis in the diagnostic and statistical manual 5. Curr. Opin. Pediatr 29, 407–413. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso C, Izquierdo A, Slattery M, Becker KR, Plessow F, Thomas JJ, Eddy KT, Lawson EA, Misra M, 2020. Changes in appetite-regulating hormones following food intake are associated with changes in reported appetite and a measure of hedonic eating in girls and young women with anorexia nervosa. Psychoneuroendocrinology 113, 104556. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljic D, Pekic S, Djurovic M, Doknic M, Milic N, Casanueva FF, Ghatei M, Popovic V, 2006. Ghrelin has partial or no effect on appetite, growth hormone, prolactin, and cortisol release in patients with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 91, 1491–1495. 10.1210/jc.2005-2304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra M, Miller KK, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, 2005. Secretory dynamics of ghrelin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescents. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab 289, 347–356. 10.1152/ajpendo.00615.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, Gallagher K, Lin A, Lee N, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, 2006. Elevated peptide YY levels in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 91, 1027–1033. 10.1210/jc.2005-1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Bencivenga R, Longobardi N, Serritella C, Maj M, 2003. Differential Responses of Circulating Ghrelin to High-Fat or High-Carbohydrate Meal in Healthy Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 5510–5514. 10.1210/jc.2003-030797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara T, Kojima S, Tanaka M, Yasuhara D, Harada T, Sagiyama K. ichiro, Muranaga T, Nagai N, Nakazato M, Nozoe S. ichi, Naruo T, Inui A, 2007. Incomplete restoration of the secretion of ghrelin and PYY compared to insulin after food ingestion following weight gain in anorexia nervosa. J. Psychiatr. Res 41, 814–820. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicely TA, Lane-Loney S, Masciulli E, Hollenbeak CS, Ornstein RM, 2014. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. J. Eat. Disord 2, 1–8. 10.1186/s40337-014-0021-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris ML, Robinson A, Obeid N, Harrison M, Spettigue W, Henderson K, 2014. Exploring avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in eating disordered patients: A descriptive study. Int. J. Eat. Disord 47, 495–499. 10.1002/eat.22217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B, Tschöp M, Frühauf E, Heldwein W, Fichter M, Otto C, Cuntz U, 2005. Postprandial ghrelin release in anorectic patients before and after weight gain. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 577–581. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Høst U, Kelbæk H, Schifter S, Rehfeld JF, Faber J, Christensen NJ, 1996. Influence of meal composition on postprandial peripheral plasma concentrations of vasoactive peptides in man. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest 56, 497–503. 10.3109/00365519609088805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Wang Y, 2012. Appetite regulation and weight control: The role of gut hormones. Nutr. Diabetes 2, e26–7. 10.1038/nutd.2011.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker JE, Ondrasik D, Chan D, Fredericks GJ, Tabisola-Nuesca E, Fernandez-Aponte M, Focht DR, Poth M, 2011. Total and acylated ghrelin levels in children with poor growth. Pediatr. Res 69, 517–521. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182181b2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince AC, Brooks SJ, Stahl D, Treasure J, 2009. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the baseline concentrations and physiologic responses of gut hormones to food in eating disorders. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 89, 755–765. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing,. [Google Scholar]

- Schalla MA, Stengel A, 2018. The role of ghrelin in anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19, 1–16. 10.3390/ijms19072117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr M, Miller KK, 2017. The endocrine manifestations of anorexia nervosa: Mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 13, 174–186. 10.1038/nrendo.2016.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlackova D, Kopeckova J, Papezova H, Hainer V, Kvasnickova H, Hill M, Nedvidkova J, 2012. Comparison of a high-carbohydrate and high-protein breakfast effect on plasma ghrelin, obestatin, NPY and PYY levels in women with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Nutr. Metab 9, 1–9. 10.1186/1743-7075-9-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp WG, Stubbs KH, Adams H, Wells BM, Lesack RS, Criado KK, Simon EL, McCracken CE, West LL, Scahill LD, 2016. Intensive, manual-based intervention for pediatric feeding disorders: Results from a randomized pilot trial. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr 62, 658–663. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal V, Misra M, 2014. Endocrinology of Anorexia nervosa in young people. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. Obes 21, 64–70. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000026.Endocrinology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smink FRE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW, 2012. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 14, 406–414. 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock S, Leichner P, Wong ACK, Ghatei MA, Kieffer TJ, Bloom SR, Chanoine JP, 2005. Ghrelin, peptide YY, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, and hunger responses to a mixed meal in anorexic, obese, and control female adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 90, 2161–2168. 10.1210/jc.2004-1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam FI, Seidel M, Boehm I, Ritschel F, Bahnsen K, Biemann R, Weidner K, Roessner V, Ehrlich S, 2020. Peptide YY3–36 concentration in acute- and long-term recovered anorexia nervosa. Eur. J. Nutr 59, 3791–3799. 10.1007/s00394-020-02210-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum GS, Ramsay M, Martel C, Samia M, Zygmuntowicz C, Porporino M, Ghosh S, 2009. Elevated circulating acylated and total ghrelin concentrations along with reduced appetite scores in infants with failure to thrive. Pediatr. Res 65, 569–573. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a0ce66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JJ, Eddy KT, 2019. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: Children, Adolescents, & Adults. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tolle V, Kadem M, Bluet-Pajot M-T, Frere D, Foulon C, Bossu C, Dardennes R, Mounier C, Zizzari P, Lang F, Epelbaum J, Estour B, 2003. Balance in Ghrelin and Leptin Plasma Levels in Anorexia Nervosa Patients and Constitutionally Thin Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 88, 109–116. 10.1210/jc.2002-020645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorella A, Brambilla F, Fabrazzo M, Volpe U, Monteleone AM, Mastromo D, Monteleone P, 2014. Central and peripheral peptides regulating eating behaviour and energy homeostasis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A literature review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev 22, 307–320. 10.1002/erv.2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SB, Mancuso CJ, Jo J, Keshishian AC, Becker KR, Plessow F, Izquierdo AM, Slattery M, Franko DL, Misra M, Lawson EA, Thomas JJ, Eddy KT, 2020. Restrictive eating, but not binge eating or purging, predicts suicidal ideation in adolescents and young adults with low weight eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord 53, 472–477. 10.1002/eat.23210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwater ML, Mancini F, Shapleske J, Serfontein J, Ernst M, Ziauddeen H, Fletcher PC, 2020. Dissociable hormonal profiles for psychopathology and stress in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychol. Med 1–11. 10.1017/S0033291720001440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.