Editor—We examined the temporal trend of in-hospital mortality of critically ill COVID-19 patients in France during the first year of the pandemic. We performed a cross-sectional, nationwide study, using data from the French Hospital Discharge Database (HDD). This database relies on the mandatory notification of each hospital stay, through a coded summary, for all public and private French hospitals. No nominative, sensitive, or personal data of patients were collected. Our study involved the reuse of previously recorded and anonymised data. The study falls within the scope of the French Reference Methodology MR-005 (declaration 2205437 v 0, 22 August 2018, subscripted by the Teaching Hospital of Tours), which requires neither information nor consent of the included individuals. This study was consequently registered with the French Data Protection Board (CNIL MR-005 #2018160620).

Patients were included according to the following criteria: adults (≥18 yr), admitted to an ICU between March 1, 2020 and March 14, 2021, with an ICD-10 diagnosis code of COVID-19.1 , 2 The following characteristics were considered: age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index,3 , 4 SAPS II (Simplified Acute Physiology Score II), invasive mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay. The outcome measure of interest was vital status at the end of the hospital stay. Deaths were assigned to the week of admission. To identify alteration in weekly mortality rates over the 12-month period, a linear regression model was performed using R, version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. No nominative, sensitive, or personal data were collected.

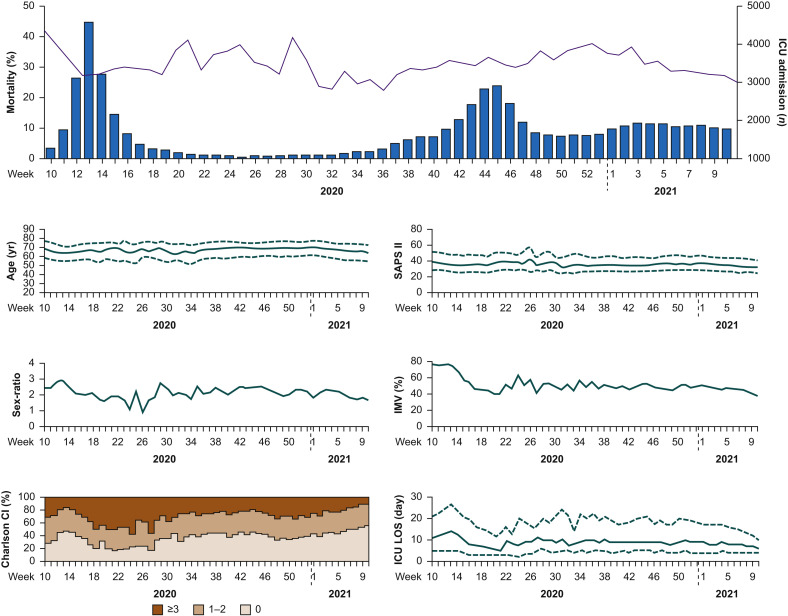

In France over the first year of the pandemic, 45 409 patients were admitted to ICU for COVID-19. Global patient characteristics were (median [inter-quartile range]): age 67 [57–74] yr; sex ratio male:female 2:3; Charlson Comorbidity Index 0: 41%, 1–2: 34%, ≥3: 25%; SAPS II 36 [27–46]; invasive mechanical ventilation 55%; ICU length of stay 9 [4–20] days; and global in-hospital mortality 31%. Trends in hospital presentation and in-hospital mortality are presented in Figure 1 . Weekly mortality rate for patients hospitalised in ICU for COVID-19 remained constant throughout the first year of the pandemic (r 2=0.009, P=0.50).

Fig 1.

COVID-19 patients hospitalised in ICU in France: 1-yr trend in clinical characteristics and in-hospital mortality rates. The purple line shows weekly mortality rates; blue histograms show the corresponding number of COVID-19 patients per week newly hospitalised in ICU (upper panel). Deaths were assigned to the week of admission. Clinical characteristics (six figures of the lower panel) are represented as median (with first and third inter-quartile ranges as dashed lines) or rate with a distribution of patients according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Charlson CI) in three categories. ICU LOS, ICU length of stay; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; SAPS II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II.

Particular trends can be highlighted. A reduction of mortality rate appeared to be observed in the first weeks of the pandemic surge (weeks 10–13, 2020). Meanwhile, a decreasing use of invasive ventilation support was observed in the same weeks. Weeks 19–30 (2020) should be interpreted with caution considering the low incidence of COVID-19 over the summer period. Changes were observed in the patient phenotype at that time: increased morbidities at presentation, lowest sex ratio, and peaks in mortality. Over the 12-month study period, age, SAPS II, and the use of invasive ventilation support were remarkably constant (except for weeks 10–13).

This study also has limitations. First, the use of administrative hospital databases introduced an inherent bias that must be considered. The strengths and limitations of using healthcare databases for epidemiological purposes have been extensively discussed.5, 6, 7 Briefly, the lack of granularity of the database could be a limiting factor, but conversely, it is an exhaustive real-life record of all patients hospitalised without initial selection bias. Second, patients were included up to March 14, 2021 and data were extracted on June 11, 2021. Consequently, missing discharge summary data are possible for patients with extremely long ICU length of stay occurring at the end of the study period, which could have biased the results of the last weeks. Last, these results are difficult to interpret without the number of cases in the general population. However, one has to keep in mind that detection of cases of COVID-19 was suboptimal at the beginning of the pandemic in the general population in France.8 The incidence rate in the general population would have represented an inconsistent indicator for the present study. We preferred to refer to ICU admissions for COVID-19 as a surrogate for the burden on the healthcare system.

We provide a national surveillance of all ICU patients with COVID-19 hospitalised during the first year of the pandemic in France. Despite an extraordinary year for science and a constant flow of new therapeutic strategies proposed during the study period, ICU outcome of COVID-19 patients was not improved.

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff of healthcare facilities who contributed to the Hospital Discharge Database implementation. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data and so they are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the institution.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guillon A., Laurent E., Godillon L., Kimmoun A., Grammatico-Guillon L. Inter-regional transfers for pandemic surges were associated with reduced mortality rates. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:798–800. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06412-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillon A., Laurent E., Godillon L., Kimmoun A., Grammatico-Guillon L. Long-term mortality of elderly patients after intensive care unit admission for COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:710–712. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06399-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quan H., Li B., Couris C.M., et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Hoore W., Bouckaert A., Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jouan Y., Grammatico-Guillon L., Espitalier F., Cazals X., François P., Guillon A. Long-term outcome of severe herpes simplex encephalitis: a population-based observational study. Crit Care. 2015;19:345. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunder S., Grammatico-Guillon L., Baron S., et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of infective endocarditis. Infect Dis (Lond) 2015;47:80–87. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2014.968608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillon A., Hermetet C., Barker K.A., et al. Long-term survival of elderly patients after intensive care unit admission for acute respiratory infection: a population-based, propensity score-matched cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:384. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullano G., Di Domenico L., Sabbatini C.E., et al. Underdetection of cases of COVID-19 in France threatens epidemic control. Nature. 2021;590:134–139. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]