Abstract

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) is highly detrimental, and its death distribution peculiarity has severely affected people’s health and the operations of businesses. COVID-19 has wholly undermined the global economy, including inflicting significant damage to the ever-emerging biomass supply chain; its sustainability is disintegrating due to the coronavirus. The biomass supply chain must be sustainable and robust enough to adapt to the evolving and fluctuating risks of the market due to the coronavirus or any potential future pandemics. However, no such study has been performed so far. To address this issue, investigating how COVID-19 influences a biomass supply chain is vital. This paper presents a dynamic risk assessment methodological framework to model biomass supply chain risks due to COVID-19. Using a dynamic Bayesian network (DBN) formalism, the impacts of COVID-19 on the performance of biomass supply chain risks have been studied. The proposed model has been applied to the biomass supply chain of a U.S.-based Mahoney Environmental® company in Washington, USA. The case study results show that it would take one year to recover from the maximum damage to the biomass supply chain due to COVID-19, while full recovery would require five years. Results indicate that biomass feedstock gate availability (FGA) is 2%, due to pandemic and lockdown conditions. Due to the availability of vaccination and gradual business reopenings, this availability increases to 92% in the second year. Results also indicate that the price of fossil-based fuel will gradually increase after one year of the pandemic; however, the market prices of fossil-based fuel will not revert to pre-coronavirus conditions even after nine years. K-fold cross-validation is used to validate the DBN. Results of validation indicate a model accuracy of 95%. It is concluded that the pandemic has caused risks to the sustainability of biomass feedstock, and the current study can help develop risk mitigation strategies.

Keywords: Risk modeling, Risk assessment in the biomass supply chain, Bayesian network, Biomass, Supply chain, COVID-19, Pandemic, Coronavirus, Virus, Dynamic Bayesian Network, Biofuel, Model Validation, Supply chain risk, Sustainability, Feedstock gate availability

1. Introduction

A family of viruses that causes illness such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the common cold, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is named a coronavirus [1]. In December 2019, a new coronavirus originated in Wuhan, China, known as acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease this virus causes is called coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19, commonly known as the coronavirus. Being infectious, the spread of COVID-19 was quite rapid; as of March 11, 2020, there were 118,000 cases in 114 countries around the globe, and 4291 people were dead. Considering this life-threatening situation, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a ‘pandemic’ [2]. As of May 20, 2020, the COVID-19 has spread to 188 countries and has affected more than 4.89 million people around the globe. This situation has resulted in 323,000 deaths, while nearly 1.68 million people have recovered [3]. According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the novel coronavirus originated from animals. It is transmitted from human to human via tiny respiratory droplets through coughing, sneezing, or when an affected person is nearby (at less than 1-m distance) to other persons [4]. These droplets can be inhaled, or people can be infected when they touch a contaminated surface (which contains such droplets) and then touch their nose, eyes, or mouth [5]. At its origin in December 2019, no vaccine was available to immunize people and protect them from the coronavirus. Moreover, there is no standard treatment for patients with the coronavirus. However, the treatment of the novel coronavirus is based on dealing with its symptoms (such as fever, cough, and difficulty of breathing) and the clinical condition of a patient [4]. Considering the facts of rapid human-to-human disease transmission and with no available vaccine for COVID-19, the world responded by closing public and private institutions, schools, colleges, universities, local and international business ventures. Moreover, travel restrictions have been put in place, and the enforced lockdown has been in effect worldwide. To prevent the spread of the coronavirus and ensure the safety of citizens, governments around the world have issued stay-at-home orders in various countries [6]. This lockdown causes significant global environmental, social and economic impacts. The global environmental impact of COVID-19 includes the decrease in emissions of pollutants and greenhouse gases. For example, the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported at the end of March 2020 that travel bans in China had resulted in a 25% reduction in the emission of carbon in the country over a four-week period, which amounts to 200 million metric tons of less carbon dioxide than in 2019 for the same period [7]. Unlike the environmental impacts of the pandemic, social and economic impacts are detrimental. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) identified emerging social issues due to COVID-19 and have reported that the people living in poverty are the most vulnerable due to the outbreak of COVID-19 and the lockdown. For example, due to a lack of safe shelter, homeless people have a high possibility of coronavirus exposure [8]. Moreover, the absence of comprehensive universal social protection systems will increase poverty and present fewer employment opportunities. The extent of economic damage depends upon the speed of the spread of the coronavirus. For example, at its initiation, the spread of this coronavirus was rapid in China. This situation reduced automobile sales by 80%, and exports fell 17.2% in January and February 2020. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported that due to this epidemic, the global GDP growth would dwindle to 2.4% from 2.9% in 2020 and can fall to zero in a worst-case scenario [9]. The supply chain of a country is an integral part of its economy, and the repercussions of the COVID-19 outbreak have served to create and accentuate external risks to supply chain sustainability. The Institute for Supply Chain Management has reported that 75% of companies have been crumbling due to transportation restrictions and are facing disruptions in their supply chain [10]. Due to the global coronavirus pandemic, business closure and lockdown implications also have inevitable and uncertain impacts on the biomass supply chain [11]. Due to the future need for sustainable energy, biomass conversion into useful bioenergy can be used as an alternate energy source to fossil fuels. However, the current pandemic is making this goal unviable. In a recent survey by Hawkins Wright studying the impact of COVID-19 on global biomass feedstock availability, 58% of wood pellet producers reported a negative impact of the coronavirus on their business. In comparison, 33% reported a reduced production due to the pandemic [12]. The participants who belonged to all regions of the world also indicated that 82% of them are negatively affected by the coronavirus, while the businesses of 14% of them are severely affected. Considering such adverse impacts of COVID-19 on the biomass supply chain, there are many risks associated with the sustainability of biomass feedstock. These include uncertainties in the biomass supply chain, biomass production, logistics, biomass harvesting, transportation, labour availability, and high preprocessing costs. In order to ensure the sustainability of biorefineries and biofuels in this uncertain time, there is a need to explore and understand the impact of COVID-19 on the biomass supply chain. The risk assessment must primarily focus on integrating sustainable biomass resources, should consider the biomass symbiosis relationship, interdependencies of risks in the biomass supply chain network, the sustainability of biomass resources, given fossil fuel prices, and the lockdown of all workers in the industry due to COVID-19. To address these challenges, this paper aims to (1) study the impact of COVID-19 on the sustainability of the biomass supply chain, (2) develop a risk assessment methodology for the biomass supply chain by integrating external and internal risks in the supply chain network (3) investigate the post coronavirus sustainability of the biomass supply chain and (4) identify the timeline when the biomass supply chain could attain pre-coronavirus conditions. Pre-analysis for the modelling includes identifying risk elements associated with the biomass supply chain, key data sources from expert knowledge, and an in-depth literature review. A dynamic risk assessment model will develop a causal network using identified risk factors and probabilistic data. The risk interdependencies in this study will be constructed using causal effects, i.e., the influence of one risk factor on another and throughout the network. The model will be tested on the biomass supply chain of a U.S.-based biofuel company, and model error will be calculated by model validation.

This paper is organized into five major sections. The introduction describes the impact of COVID-19 on the biomass supply chain and includes a brief discussion on the integrated biomass supply chain. The second section is based on a literature review of the pertinent literature. This section is further classified into two subsections: the first part presents the current methodologies used to assess the risks to the biomass supply chain. The second part highlights the literature of the dynamic Bayesian network (DBN). The literature review is summarised by identifying research gaps and the need for the current study. The third section outlines the proposed methodology and validation and is further divided into two subsections, a case study of a U.S. biofuel company and the model’s applications to it. The fourth section is results and discussion, presenting the results and reviewing the findings of this research work. Then the research is concluded, along with suggested future work directions.

1.1. Integrated biomass supply chain

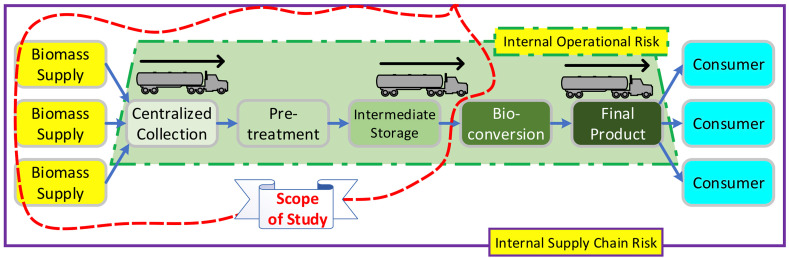

Typically, a biomass supply chain consists of (i) a supply chain network including biomass handling, preprocessing and the movement of material from biomass origin to biorefineries, (ii) production of biofuels in biorefineries, and (iii) product distribution to the consumers [13]. Due to these business functions, the current biomass supply chain management is a conundrum that plays a crucial role in managing bioenergy and bioproduction processes [14]. Various risks are associated with the biomass supply chain that distinguish it from other products' traditional supply chains. Such risks are uncertainty in biomass availability, limited biomass supply due to seasons and weather, fluctuations in physical and chemical compositions of biomass, biomass transport density, geographical distributions of feedstock, local transportation systems, and distribution infrastructures [15]. The complexity is compounded when costs of raw feedstock and biorefineries operations are compared with the market price of fossil fuels. As highlighted by Ref. [16], the biomass supply chain is an integration of four system components: (i) harvesting/collection of biomass from single or multiple locations and the pre-treatment, (ii) intermediate storage of biomass, (iii) transportation, and (iv) bioconversion. In addition to these discrete processes, the final product's (biofuel) distribution also needs to be embedded in the biomass supply chain, as shown in Fig. 1 . In Fig. 1, all components are interconnected and interdependent, and therefore no distinct boundary can be drawn between two pieces. In this supply chain, biomass supply is the first and foremost point for biofuel production.

Fig. 1.

An integrated biomass supply chain.

Biomass is defined as any renewable organic material which is available regularly, such as crops and their wastes, woods, and waste of wood processing, algae, aquatic plants, animal manure, and wood and its residues. Other biomass materials are waste from food processing, waste cooking oil, food waste, and waste materials which produce fuels, energy, and chemicals [17]. Plant-based organic materials that are not meant to be used as food, such as palm kernel shells, rice husks, fruits' wastes, and paddy straw, are also categorized as biomass feedstock [15]. Moreover, non-edible resources such as jatropha, Linum usitatissimum (linseed), Azadirachta indica (neem), etc., and waste cooking oil are also used as biomass feedstock [18]. Studies have identified that various factors, such as inappropriate crop harvesting, unfavourable weather, operational constraints, and the geographical region where the biomass is cultivated can affect biomass availability [19]. Biomass is considered to remain biologically living matter and chemically active throughout the biomass supply chain. For example, for algae biomass, the active biological ingredients are proteins, polyphenols, polysaccharides (biopolymers of glycosidic bonds and monosaccharides), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), minerals, and dyes [20]. The biological activity in biomass can alter the composition of the biomass, which could affect the biomass’s conversion to biofuel in the biorefinery. Using waste cooking oil as a source of biomass feedstock, the water contents and free fatty acids are dominant factors. Hence the quality of biomass is a crucial risk factor in maintaining the efficiency of the biomass supply chain. In this regard, appropriate harvesting and collection schedules can help ensure the quality of biomass is within the desired limitations, up to the point when it is delivered to the doorstep of the biorefinery. As shown in Fig. 1, pre-treatment activities are performed on the biomass collection site before sending the biomass to a biofuel processing facility.

Pre-treatment of biomass includes chemical, physical, biological, and physicochemical processes, as highlighted in the literature [21,22]. Depending upon the characteristics of raw material and end products, the pre-treatment or preprocessing increases biomass porosity, enhances the efficiency of the enzyme, improves the accessibility of the enzyme, and minimizes the losses of carbohydrates [23]. In preprocessing, the dense biomass feedstock is converted to be less dense, which reduces associated biomass costs such as transportation, handling, and storage, and increases the product quality. The preprocessed biomass is transported to biorefineries, where it is converted into bioenergy (biofuel and electricity) through the bioconversion process. There are three leading technologies for the bioconversion process: thermochemical, biochemical, and physicochemical [24,25]. Thermochemical conversion of biomass is mainly performed using three pathways, i.e. pyrolysis, gasification, and combustion [26].

In contrast, biochemical conversion involves two primary process alternatives; anaerobic digestion and fermentation [27]. The physicochemical transformation has various process options, such as ammonia fibre explosion, steam explosion, and wet explosion [28]. This conversion is out of the scope of the current study. The scope of the present work is sketched in Fig. 2 and includes biomass supply collection to the gate of a biorefinery. The final product, shown in Fig. 1, could be of two categories: biofuels or biochemicals. The primary products of a biorefinery include biofuels, such as biodiesel (produced from animal fats and vegetable oils), biogas (produced from decomposing food scraps, animal manure, yard waste in landfills) or ethanol (also called bioethanol, produced from crops of sugar cane and corn). The biochemicals are derived from value-added products such as styrene and phenolics used for various purposes [29]. Transportation connects all components in a biomass supply chain, and hence transportation cost plays an essential role in an economical and sustainable supply chain network. As highlighted by Ref. [15], transportation scheduling and carriage routes are key risk factors in biomass logistics. A viable schedule helps to ensure that both feedstock and finished products are delivered on time to the respective biorefinery and consumers. Selecting an appropriate transport route helps to minimize travel time and cost; it also reduces the environmental impacts of activities in the biomass supply chain.

Fig. 2.

Scope of the study.

2. Literature review

The literature review of this paper consists of two subsections. The first section highlights the current state-of-the-art methodologies for risk assessment of the biomass supply chain. The second part of the literature review discusses the paradigm of the dynamic Bayesian network (DBN).

In the past, various researchers have proposed techniques to model biomass supply chains. In a study, a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model was presented to assess the size and geographic location of a bioethanol plant in Austria [30]. The model studied various stages of biofuel production, including biomass supply chain, heat utilization in biofuel production, and demand for fossil and biofuels. A mathematical model was presented in another study to model biomass supply chain and logistics in a biofuel production facility [31]. The proposed model could identify the location, number and size of biorefineries based on available biomass. The study applied the proposed model to the biomass supply chain in the State of Mississippi. Another study presented a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to design the supply chain risk of biomass-based ethanol [32]. The model used a case study of an Italian biomass-based ethanol system to analyze the ethanol supply chain's strategic design and biomass planning decisions. Their model was able to capture the multiple biomass technology choices and considered the risk mitigation preferences of decision-makers. Another work proposed a multistage stochastic programming model to deal with uncertainties in quality (operational factor), the availability of biomass feedstock, and their impact on net profit [33]. The study showed a trade-off between biomass quality and profit and helped control variations in storage levels. In a study, a Bayesian network (BN) approach was used to predict the complex behaviour of risk propagation in the supply chain [34]. They studied the resilience index and risk exposure indices for various nodes within the supply chain network. Their results showed the vulnerable nodes due to disruption propagation in the supply chain network and were helpful in supply chain risk management. A simulation modelling approach was used to evaluate the risks of operational disruptions on the cost of the biomass supply chain, production level, and inventory [35]. The study considered three scenarios, and the simulation model was analyzed for seven years. The study showed that risk vindication alone at a facility is not enough. The concurrent inclusion of failure dependencies at the system level is required for the sustainable design of the biomass supply chain.

In a recent study, researchers studied operational and disruption risks to the bioethanol supply chain [36]. They proposed a MILP based model to identify, analyze the design, and risk planning of a supply chain network of multi-feedstock lignocellulosic bioethanol. Using a case study in Iran, their model provided optimal supply chain decision variables. In another study, investigators evaluated reduction opportunities of supply, market, and operational risks for the supply chain of a cellulosic biorefinery, which adopted a distributed depot concept [37]. Their study was based on geographically distributed depots and showed that operational and market risks were reduced for a distributed depot supply system.

2.1. Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN)

A Bayesian Network (BN) is a directed acyclic graph (DAG) in which nodes represent random variables, and the directed arcs show the conditional dependency of one node (called parent) on another (called child) [38]. The influence of parent on child corresponds to a directed edge. The strength of parent and child nodes is defined by assigning marginal and conditional probability Table 1, Table 2. A BN characterizes a factorization of joint probability (JP) distribution over two (bivariate distribution) or more than two (multivariate distribution) random variables. Despite such characteristics, BN models cannot consider temporal information [39], which means a BN cannot model numerous phenomena over time. This limitation is overcome by the Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN). A DBN helps to model and quantify temporal relationships among different data points [40]. It represents the ‘evolution’ of given random numbers as a function of the time steps sequence (a discrete sequence). Intuitively, a DBN is the ‘evolution’ of risk over time. The terminology of ‘dynamic’ in DBN does not mean the change in network architecture but the change in model parameters [40]. A ‘static’ BN is denoted by nodes (N) and edges (E) that connect the nodes in a directed position. For each node (denoted by y), a conditional probability distribution (CPD) is associated. The network structure, consisting of directed relationships between parents and child nodes, interpreted with their CPDs, defines a BN. The factorized joint probability (FJP) on N (denoted by P(N)) is represented as:

Table 1.

Details of Waste Cooking oil drop-off sites.

| Tag in Fig. 6 | Name | Locations |

|---|---|---|

| A | Bainbridge - Transfer Station | 7215 Vincent Road Bainbridge, WA 98110 |

| Ba | Federal Way - French Lake Dog Park | 31531 1st Ave. S. Federal Way, WA 98003 |

|

Mahoney Environmental Restaurant Cooking Oil Recycling | 6333 1st Ave. S. Seattle, WA 98108 |

| D | SODO - Republic Services | 54 S. Dawson St. Seattle, WA 98134 |

| E | Madison Park - Bert’s Red Apple | 1801 41st Ave. E. Seattle, WA 98112 |

| F | Mercer Island - Presbyterian Church | 3605 84th Ave. SW Mercer Island, WA 98040 |

| Ga | Olympia - Thurston County HazoHouse | 2420 Hogum Bay Rd. N.E. Olympia, WA 98516 |

| Ha | Redmond - City of Redmond Drop Offsite | 8703 160th Ave, NE, Redmond, WA 98052 |

| I | Renton - Republic Services | 501 Monster Rd. SW Renton, WA 98134 |

| Ja | City of Auburn | 1020H Street S.E., Auburn, WA 98002 |

| K | Kent - Republic Services | 22010 76th Ave S, Kent, WA 98032 |

| La | City of Sedro-Woolley Recycling Facility | 315 Sterling St., Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 |

| Ma | Whatcom County Disposal | 3505 Airport Dr, Bellingham, WA 98226 |

Not shown in Fig. 6 due to space limitations.

Table 2.

Risk categories and risk factors.

| Risk Category | Risk factors | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative factors (QL) | Quality of biomass (QL1) | This risk factor indicates the quality of waste cooking oil collected. |

| Cooking temperature (QL2) | The temperature at which fresh cooking oil is cooked and transformed into waste cooking oil. | |

| Changes in waste cooking oil composition (QL3) | This factor refers to the chemical composition of waste cooking oil, e.g., changes in free fatty acids, and moisture contents. | |

| Usual collection schedule (QL4) | This risk factor shows the usual schedule to pick up the waste cooking oil. | |

| Preprocessing cost (QL5) | This risk element indicates the cost to process waste cooking oil to make it useable before using it to produce biodiesel e.g. filtration, sedimentation, and moisture removal from waste cooking oil. | |

| Quantitative factors (QT) | Unavailability of fresh vegetable oil (QT1) | This factor shows the unavailability of fresh vegetable oil in the market due to market closures and transportation halts at a large scale. |

| Less recycling by the consumers (QT2) | It represents the less use of fresh cooking oils by consumers due to market closure and subsequently less recycling of used cooking oil. | |

| Closure of collection sites (QT3) | It indicates the closure of collection sites depicted in Table 1. | |

| Restaurants not open (QT4) | It shows the closures of restaurant businesses due to COVID-19. | |

| Quantity of biomass available (QT5) | Indicates the amount of biomass available as feedstock to produce biodiesel. | |

| Labour (L) | Labour availability (L1) | It shows the availability of the labour working in biomass supply chain networks such as managers, engineers, production staff, collection teams, drivers, and other staff. |

| Operational cost (L2) | It is the expenses incurred to run business operations such as administrative costs, maintenance costs and salaries of the employees. | |

| Biomass transportation (BT) | Robust transport schedule (BT1) | It refers to the transport schedule to collect waste cooking oil. |

| Viable transport route (BT2) | It shows the routes adapted to collect waste cooking oil and transfer it to the biodiesel production site. | |

| Sustainable transport planning (BT3) | Transport planning refers to policies to move waste cooking oil from its source to the factory gate. | |

| Transportation cost (BT4) | It is cost associated with transporting waste cooking oil to bio-conversion site (Mahoney Environmental® in the current case study). | |

| Oil (OL) | Fuel demand (OL1) | It indicates the demand for fossil-based fuel for transportation such as diesel and gasoline. |

| Fuel prices (OL2) | This risk factor refers to the market price of fossil-based fuel. | |

| Production of fuel (OL3) | It denotes the production of fossil-based fuel. | |

| Pandemic (P) | Lockdown (P1) | It indicates the condition in which people are required to stay at home, and no free movement is allowed. |

| Business operational (P2) | It refers to the working of a business. | |

| Transport (Regular transportation) (P3) | It shows the regular public and private transport by roads, air, and water. | |

| Effectiveness of vaccine (V) | This factor refers to the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine. | |

| Feedstock gate availability (FGA) | – | It indicates the availability of waste cooking oil at the factory gate. |

where indicates the parents of child node y. This definition of ‘static’ BN is transformed to a ‘dynamic’ mode by considering two aspects: first, the initial or prior distribution of random variables in the static BN at time 0. Secondly, the dynamic two-step BN is investigated; this describes the transformation from the previous time t-1 to the current time t, having the probability P( ) for any node y, which belongs to N in a DAG. Hence, the JP for two sets of nodes, namely and , is:

The computation of the JP law is performed by ascertaining the sequence in the network over a series of times. For the total length of the path Z and JP of the initial network P(), the probability of transforming from to Z is computed as:

Thus, DBN follows the Markov property, which states that the CPD at a given time t is solely dependent upon the state at the previous time, denoted as t-1 [41]. A DBN generalizes the Hidden Markov Model (HMM). A more complex DBN could have multiple input variables connecting last time slices, as shown in Fig. 3 . A DBN defines the dependencies between parent and child nodes over time. As shown in Fig. 3, nodes (y1 to y5) in a DBN are still linked through a DAG; nevertheless, cycles between nodes are allowed in the DBN. A DBN is a series of BNs developed for varying time units; each BN is called a time slice. As shown in Fig. 3, temporal links connect time slices, and the outcome is a dynamic model. In the biomass supply chain, this property can help to study the dependence of current and previous years' variables—for example, the dependence of this year's biomass supply on last year’s rain. In DBN, all times are zero-based, which means t = 0, rather than t = 1, which indicates the first time step.

Fig. 3.

(a) An ordinary Bayesian network (B.N.) having five nodes, (b) Dynamic Bayesian network showing three slices.

Previously, the DBN has been used for modelling various systems such as predictions of crop growth [42], process safety [43], system performance measurements [44] and healthcare [45]. Although the DBN has been used in various fields of study, it has never been used to address the dynamic behaviour of the biomass supply chain system. To fill this research gap, in this paper, a DBN for the biomass supply chain is proposed, and the application is shown using a case study. Fig. 2 indicates two categories of biomass supply chain risks: internal operational risks and internal supply chain risks [46]. Internal operational risks refer to risks to the regular operations, such as risks to the distribution, manufacturing, process improvements, product development, and infrastructure. The internal supply chain risks indicate the potential risks to the upstream and downstream supply chain of the biomass, such as unpredictable demand by consumers or interruptions in the availability of biomass feedstock or bioproducts. As evident through the literature review, the traditional risk assessment techniques have only focused on internal operational and internal supply chain risks to the biomass network. However, the biomass supply chain risks are evolving, especially with the current pandemic conditions due to COVID-19. The impacts of external risks on the biomass supply chain and the interactions of external risks with supply chain components have never been addressed. This work aims to fill this research gap. This paper has three primary contributions and innovations; (1) prior research on biomass supply chains has been focused on studying the static behaviour of the biomass supply chain and does not consider time variability in the supply chain system, and hence cannot provide biomass supply chain behaviour over time. This research investigates such dynamic behaviour. This study provides a dynamic framework to analyze the evolution of biomass supply chain risks over time. (2) This paper is the first to assess the probabilistic impact of COVID-19 on a biomass supply chain and identifies the recovery time of loss due to the coronavirus. (3) This study provides a risk network model which captures the uncertainties of biomass supply chains. It aims to answer the questions of the future impact of COVID-19 on the biomass supply chain. How much will the cost of the biomass supply chain be affected due to this coronavirus? How much is the sustainability of the biomass supply chain affected due to the ongoing pandemic? When will the biomass supply chain return to the precoronavirus situation? What will be the impact of fuel prices on biomass availability? The results from this research work can help governments, investors, biomass supply chain managers and biomass business owners to make informed decisions as they assess the post-coronavirus situation. This study can help them to evaluate, manage, minimize, and mitigate the risks to their businesses due to COVID-19. The dynamic risk modelling framework for the biomass supply chain risk is applied to a biofuel company located in Washington state of the United States of America (USA). The case study helps to illustrate the proposed methodology, results and findings.

3. Methodology

The research methodology in this study consists of five steps. The prime objective of this work is to investigate the temporal and quantitative strengths of the relationships among various risk factors of the biomass supply chain. The definition of strength is reported in the literature [47] and is applied here. The input data in this study were the interdependency relationships among risk factors, which were defined using experts’ elicitation. In this study, experts were a research group consisting of three senior university professors in a U.S. university who have an in-depth knowledge of the biomass supply chain and extensive experience in chemical engineering research and development. The steps followed include:

Step 1: Identification of risk categories

In this step, experts identified six risk categories associated with the biomass supply chain. Those were qualitative factors, quantitative factors, labour, biomass transportation, oil, and the pandemic. The qualitative factors were defined as those risk factors related to the quality or characteristics of biomass, such as the chemical and biological composition of the biomass. Risk factors in quantitative conditions were defined as those risk factors that could affect the quantity or amount of biomass available, such as the closure of biomass production sites. The labour category consisted of those risk factors related to the workforce employed in the biomass supply chain, such as labour availability. The biomass transportation category was defined as risk factors associated with moving biomass from one point to another—for example, the transportation schedule. The oil category was described as a category that consists of risk factors related to fossil-based oil, either diesel or gasoline, used in the transportation of the biomass in the biomass supply chain network: for example, oil demand. The pandemic risk category was defined as those risk factors based on the epidemic situation, such as a countrywide lockdown.

Step 2: Identification of risk factors

In this step, risk categories defined in step 1 were further classified into risk factors using previously available studies [37,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. The identification of risk factors is based on the risk category under study and the type of raw material used to produce biofuel—for example, waste cooking oil or crops.

Step 3: Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) modelling

In this step, a DBN model was developed. This task was accomplished in two phases, (a) structural learning and (b) parameter learning. Structural learning considered the interdependencies among the stochastic risk variables defined in step 2 and resulted in the graphical structure of a dynamic BN. Parameter learning was used to define prior marginal probability distributions of root nodes in the network and conditional probability distributions of non-rooted nodes in the BN. A detailed description of the two steps is provided below.

Step 3a. Structural learning

This step consisted of building the interdependency relationships among risk factors through experts’ knowledge. The expert elicitation technique was used to define such relationships, as discussed in the literature [53]. This structured expert elicitation technique has been extensively used in the literature, such as in Refs. [[54], [55], [56]]. Experts defined the interdependencies among stochastic risk factors based on the causal relationships between stochastic nodes. Once the relationships were identified, the directed arcs were drawn between nodes as per causality defined by the experts. The result of this step was a graph structure of B.N.

Step 3b. Parameter learning

In this step, prior probability distributions were defined for root nodes at time t = 0 (first-time step), and conditional probability tables (CPTs) were defined for non-root nodes at time t = 0. Since COVID-19 is new and there are no historical data available, experts’ judgments were used in this step. The outcome of this step was a B.N. with temporal relationships, i.e., a DBN. The analysis was performed for ten time steps (t = 9). GeNIe Modeler by Bays Fussion, LLC (https://www.bayesfusion.com/genie/) was used as a tool to build DBN and perform Bayesian inference, as discussed in the next step.

Step 4. Risk-based inference

In this step, the risk-based inference was performed using the DBN developed in step 3. The temporal feature of GeNIe allowed updating beliefs of all time steps at once rather than observing results one at a time. This step provided the posterior probabilities of each node in DBN, which were conditionally based on the evidence. The computational mechanism of solving DBN has been presented earlier. The probabilistic results were reported and discussed.

Step 5: Model validation

As a final step of this methodology, the model presented was validated using the k-fold cross-validation method. This method helped to provide information on the robustness and accuracy of the model in predicting the outcomes. The use and reliability of this method to predict model accuracy has been extensively studied in the literature, for example [[57], [58], [59], [60]]. A database file (presented in Data-In-Brief) consisting of 100 cases (n = 100) was compiled, and each case had values of the response variable (biomass feedstock gate availability) and covariates. The database file consisted of 100 samples with known values of input nodes (as presented in the model) and the node of ‘biomass feedstock gate availability’ (final output node). The randomized data file was divided into ten equal sets or segments (k-value in k-fold validation). The value of 10 sets is the optimal value of k in k-fold cross-validation, as supported in the literature [60]. The first ten parts of data, representing ten sets (n = 100/k = 10 = 10), were set aside, and the model was parameterized with the leftover cases, i.e., (n-n/k). Then the model was tested against other sets of the database for accuracy and comparison of model results to known outcomes in each case. This procedure was repeated for all ten segments. GeNIe was used as a tool to develop randomized subsets and to perform k-fold cross-validation. Results were presented and discussed in terms of the accuracy of nodes and selected receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

3.1. Case study of a U.S. Biofuel company

To demonstrate the applications of the proposed methodology, a case study of a U.S. biofuel company in Washington state is presented. At the time of doing this research on May 10, 2020, there have been 1.307 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., while 78,794 people there have lost their lives due to COVID-19 [61]. The number of confirmed cases in different states is shown in the choropleth map sketched in Fig. 4 . On March 13, 2020, the U.S. government declared a national emergency to deal with the COVID-19 crisis [62]. As of April 7, 2020, several states ordered the closure of businesses, workplaces, and schools and enforced social distancing [63], followed by a partial or statewide lockdown all over the U.S., as shown in the choropleth map of Fig. 5 . This situation means that the U.S. economy was shut down, and employees and employers could not work or receive customers. Road, air, and sea transportation were also limited. This economic shutdown also closed biomass business units across the country. In the U.S., various biomass feedstocks are being used, such as crops (sugar beets and sugarcane), crop residues (bagasse, barley straw, corn stover, rice straw, grain sorghum stubble, and wheat straw), wood (forest residues, primary mill residues, urban wood, secondary mill residues), and waste cooking oil [18]. For this research work, Mahoney Environmental® company, located in Washington state, was chosen to elaborate on the methodological framework. The company collects waste cooking oils, which are used to produce biodiesel, and has been a leader in recycling waste cooking oil for over 65 years in the U.S. Regularly, the company collects used cooking oils from more than thousands of shopping malls, food restaurants, bars, commercial food producers, stadiums and military stations across Washington state and produces low-cost commercial-grade biodiesel along with co-products such as solvents, lubricants and glycerine at their plant site, shown in Fig. 5. Residents of Seattle and nearby have also dropped off their used cooking oil at various drop-off locations for waste cooking oil, shown in Fig. 6 , and details of all 13 sites are presented in Table 1 . Due to COVID-19 and the lockdown, the collection of used cooking oil, its transportation to the chemical plant site, and biodiesel distribution have been negatively affected. This study aims to analyze the probabilistic magnitude of this impact and assess the risk-based performance of the biomass supply chain using the proposed model. Risk in this study is defined as the probability of having an insufficient supply of waste cooking oil from all 13 drop-off locations to the gate of Mahoney Environmental® for the pre-treatment of waste cooking oil and subsequently the shortfall of biomass for biodiesel production. The objective of the current case study is to identify and analyze the risks to waste cooking oil feedstocks which would help ensure a continuous supply to the Mahoney Environmental recycles under investigation. Steps presented in the methodology section are applied to this case study, and results are presented and discussed in the next section.

Fig. 4.

Confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the USA* as of May 10, 2020. Data adapted from Johns Hopkins CSSE [61] *Notes: Names of some states are omitted to avoid label clustering. Map developed in Datawrapper.

Fig. 5.

Choropleth map of the United States* with statewide business closures due to COVID-19 as of April 3, 2020 [64]. The red circle shows the biofuel plant location on the map. *Notes: Names of some states are omitted to avoid label clustering. Map developed in Datawrapper.

Fig. 6.

Public cooking oil drop-off locations for waste cooking oil in Seattle and nearby vicinities. Details are presented in Table 1. For an interactive map, readers can click here. (Map courtesy of Google Maps).

4. Results and discussions

The results of six risk categories and their associated subcategories as defined in steps 1 and 2 of the methodology are presented in Table 2 . As shown in Table 2, each risk category is further classified into subcategories of risk factors. In total, 23 subcategories are defined. As shown in Table 2, the risk classification is based on risks associated with the biomass supply chain of the Mahoney Environmental® company. Table 2 also shows the definitions of risk terms identified in this study.

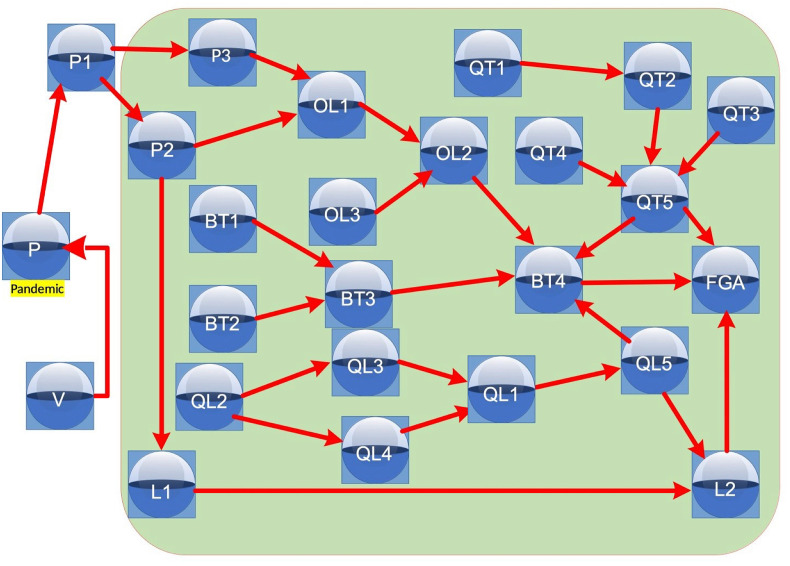

The results of static BN are shown in Fig. 7 , which shows the interdependencies among risk factors. It indicates both external and internal risks. External risks are the pandemic situation and lockdown, while the internal risks are shown in the green area in Fig. 7. Fig. 7 is a static BN model of the problem and includes the associated risk factors and their interdependencies. Arcs in Fig. 7 indicate the probabilistic relationships among variables and are quantified by the conditional probability distributions, as presented and discussed in the attached Data-in-Brief. Each directed arc is represented in red colour while the direction of the arrow indicates the direction of causality. Fig. 7 shows that the pandemic causes a lockdown situation that influences both businesses and regular transportation and transit services within Washington.

Fig. 7.

A Bayesian Network (BN) model for the biomass supply chain. The area in green represents the internal risks.

Due to the business closures across Washington state, there is an impact on the availability of the labour to perform routine day-to-day operations in the biomass supply chain. Fig. 7 also reveals that the demand for fossil-based fuel and its production affects its market prices. The results of the BN indicate that the closures of restaurants and collection sites to collect waste cooking oil have an impact on the quantity of biomass available. This outcome is true since restaurants and collection sites are the major places to collect waste cooking oil for the Mahoney Environmental® company. Their closure due to COVID-19 causes an impact on the quantity of biomass collected. Results in Fig. 7 also show that due to less labour available to collect waste cooking oil from the suppliers, there is an impact on the collection schedule. Results also reveal that a high cooking temperature causes a change in the chemical composition of waste cooking oil, affecting the quality of biomass, which influences its preprocessing cost. One of the prominent features of the model is the impact of the vaccine effectiveness on the network. As shown in Fig. 7, vaccination affected the pandemic. This result is based on the fact that immunization induces the reduction of the population's vulnerability to the risk of COVID-19.

Results in Fig. 7 show that three risk factors are affecting the gate availability of biomass feedstock, the transportation cost, the quantity of biomass available, and operational costs. The probabilistic results of the BN analysis provide more depth to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the biomass supply chain. Due to space limitations, the results of selected risk factors are discussed here. The results of P(Low QL1/QL3, QL4) show a probability value of 0.851, which indicates that, based on changes in the composition of waste cooking oil and due to the unavailability of the usual collection schedule, there is a high probability that the biomass collected will be of low quality, due to the pandemic. The results of preprocessing cost validate such findings, since P(High QL5/Low QL1) = 0.846, indicating a higher probability of preprocessing cost based on the low quality of this biomass. The high preprocessing cost influences the operational cost, and its probability is given as P(High L2/High QL5) = 0.821. This result shows that there is a strong possibility to have an increased operational cost of the biomass supply chain, based on the high preprocessing cost of the biomass.

In terms of the available quantity of biomass, the results indicate that P(Less QT5/QT2, QT3, QT4) = 0.93. This result shows that the COVID-19 has a significant impact on the quantity of biomass available, given that restaurant and waste oil collection sites are closed. There is less recycling of waste cooking oil. The results of BN in Fig. 7 also help to understand the impact of COVID-19 on fuel prices. The probabilistic analysis shows that P(Low OL2/Low OL1, High OL3) = 0.891. This result indicates that due to COVID-19, there is less demand for fossil-based fuel, and due to its high production, it suffers from lower prices. This situation indicates an abundance of fuel in the market. The DBN analysis shows the evolution of these results over time, and a screenshot of DBN simulation in GeNIe software is shown in Fig. 8 .

Fig. 8.

A Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) model for biomass supply chain.

Fig. 7 shows how the risk factors influence one another in non-temporal behaviour, while Fig. 8 enables us to examine the temporal behaviour of these risk factors over time. Fig. 8 also allows us to study the influence of COVID-19 on the performance of the supply chain network, as it indicates the DBN of the biomass supply chain. The model presented in Fig. 8 helps to understand the impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the biomass supply chain network. The use of dynamic BN permits us to perform quantitative modelling of various risk factors that influence the gate availability of biomass feedstock. The DBN presented in Fig. 8 is an extension of static BN, shown in Fig. 7. DBN supports the temporal evaluation of risk factors over a discretized timeframe. As shown in Fig. 8, the timeline is divided into ten time slices, and the DBN aids each node to be conditionally dependent on its parents. At the same time, DBN also allows a node to be conditionally dependent on its parents, at previous time slices.

The latter behaviour is shown in Fig. 8 as a number within the small square. For example, in Fig. 8, number 2 in the small green square on low fuel demand indicates that there are two time slices in temporal dependencies of low fuel demand. While the arc between transport and low fuel demand shows number 4 in a small square, this arc shows the temporal influence, while its number indicates its order, also called lag. Lag in DBN shows the order of the temporal (time-based) link. The number 4 suggests that the influence of transport spans over four time steps. In other words, a temporal link with order four from the transport node to another node, low fuel demand, as shown in Fig. 8, is interpreted as transport links to low fuel demand in the later future, i.e., four-time intervals or steps. The low fuel demand node has a link from the transport node in the past, i.e., four-time intervals or steps in the past. Results in Fig. 8 show that the transportation cost is influenced by low fuel prices, sustainable transport planning, high preprocessing cost, and less quantity of biomass available.

In terms of the quality of biomass, changes in biomass composition, and the absence of the usual collection schedule, cause low quality biomass. Results in Fig. 8 also show that a decrease in labour availability results in high operational costs. The graphical structure of the DBN model, shown in Fig. 8, is similar to its static BN model, shown in Fig. 7, except that there are additional arcs in the DBN model that quantify the temporal relationships among risk factors. The dynamic or temporal arcs represent the changes in the probabilistic values of risk variables over time. Fig. 9 captures two unrolled time steps (Step 0 and 1) of the DBN model presented in Fig. 8. Unrolling helps to covert DBN into its equivalent static BN, which quickly helps to understand the DBN structure. As shown in Fig. 9, all variables are repeated in each time step except the pandemic, effectiveness of vaccine and lockdown. Such behaviour of the model is because these three variables do not repeat in each time step but influence the rest of the variables in each time step.

Fig. 9.

Unrolled DBN model for the first two-time steps.

Considering the observed dynamic evidence of QT5, BT4, and L2, the DBN model encodes the probability distribution over gate availability of biomass feedstock. This simulation results in calculating the risk of having no biomass feedstock available at the factory gate, given the conditions of low transportation cost, high operational cost, and less quantity of biomass available at a given time, i.e., P(FGA t/E1 ), where E = QT5t-1 = less, BT4t-1 = low, L2t-1 = High. It shows that conditional probability distribution for gate availability of biomass feedstock depends on the results in the previous time step for risk factors of the available quantity of biomass, transportation cost, and operational cost. The results are drawn in Fig. 10 , which shows the probability of having no biomass feedstock at the factory gate, given this dynamic evidence, i.e., P (FGA (no)/E). The plot in Fig. 10 shows the risk of having no biomass feedstock availability at the company’s gate over ten time steps. This result can help develop production planning and the optimal time for biodiesel production in a pandemic situation.

Fig. 10.

Risk of no biomass availability.

Results in Fig. 10 show that in the pre-coronavirus situation, gate availability of biomass feedstock was regular, and there was no external risk of COVID-19. Fig. 10 shows that when the pandemic hits Washington state, the probability of unavailability of biomass supply at the company’s gate reaches its maximum value of 0.98 in the lockdown situation. The high unavailability of biomass indicates the need to secure waste cooking oil from more remote locations than shown in Table 1. This action may not be environmentally friendly, as more vehicle transportation would release more carbon by fuel burning, and negatively affect the environment. Moreover, collecting waste cooking oil from farther places would not be economical, as it would involve the additional costs of the operations of the biomass supply chain.

Results also indicate that it would take at least one year for probability to reduce to 0.084. As shown in Fig. 10, this value should approach zero, as in the pre-coronavirus situation; however, such results are not obtained until the fifth year. In other words, it will take five years for the biomass supply chain to complete recovery from the COVID-19 hit. It is noteworthy here that the U.S. House of Representatives, on May 15, 2020, voted to pass the COVID-19 stimulus package. The bill, known as the ‘Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act or the HEROES Act’ aims to provide relief to biofuel producers in the U.S. The financial benefits include providing a 45 cents per gallon payment to qualified biofuel producers from January 1, 2020, to May 1, 2020 [65]. For interested readers, the entire bill is available at the House of Representatives, accessible at [66]. With these financial incentives, the time of five years of recovery, as revealed in this study, may be shortened.

The DBN model provided lays the imperative groundwork for probabilistic approaches to assess the disruption to the biomass supply chain due to fuel prices. Supply chain networks of biomass feedstock may be complex systems. They may comprise many interrelated and interconnected factors that may introduce nonlinearity into the system. Depending upon the complexity of the network, discretization can be introduced into the model, which can help capture and compute non-linear relationships among risk variables [67]. Moreover, discretization would help to reduce computational power to solve the model [68]. The results of the impact of COVID-19 on fuel prices are drawn in Fig. 11 . Fig. 11 shows that the probability of the fuel price being lower is higher at the start of the coronavirus spread, shown in the blue colour line. In other words, the likelihood of fuel prices being higher is low at the beginning of the coronavirus spread (shown in the orange colour line). Values of both curves in Fig. 11 are complementary to each other. The DBN predicts that the probability of the fuel price being higher will gradually start to increase and will take one year to reach a value of 0.84; after this time, there is a gradual increase in fuel prices over time. However, the fuel price does not reach a pre-coronavirus situation, even after nine years, as shown in Fig. 11. The increasing trend in fuel prices in Fig. 11 is compared with fuel price trends from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Their data of weekly U.S. regular convention retail prices of gasoline are drawn in Fig. 12 . The data of the U.S. EIA show that after May 4, 2020, there is an increasing trend in fuel price. Hence, this confirms the results of this study. The methodological framework presented in this study is consistent with [69], in which researchers used DBN to model risk assessment of flood control operations.

Fig. 11.

Impact of COVID-19 on fuel price.

Fig. 12.

Prices of regular gasoline in the U.S. (November 4, 2019, to June 15, 2020), data adapted from [70].

As the DBN model shows the changes in probabilities of the various risk factors of the biomass supply chain over time, it can help develop contingency plans to manage risks to the biomass supply chain. To demonstrate the operationalization of the model, this study chose a biofuel production facility that utilizes waste cooking oil as a raw material. However, the model presented can be applied to supply chain networks of other biofuel raw materials such as sugar beet, corn, sugarcane, jatropha, grass, switchgrass, woody crops (lignocellulosic biomass), woodchips, agricultural residues, soybean oil, rapeseed oil, or other plant oils. In any case, the risk categories of quality should include risk factors such as biological activities and a proper harvesting schedule. The risk category of quantity should consist of unseasonable weather, rainfall, and droughts. However, the risk factor of transportation should be based on vehicles to collect the biomass from fields and its transportation to bioconversion sites. The methodological framework presented is consistent with [69], in which, using experts’ opinions, researchers developed a DBN model to perform a risk assessment of flood control operations. Future work is recommended to expand the analysis by including the risk factors associated with bioconversion and biofuel delivery to customers. Since this will introduce structural complexity in the network, a dynamic object-oriented Bayesian network approach [71,72] is recommended.

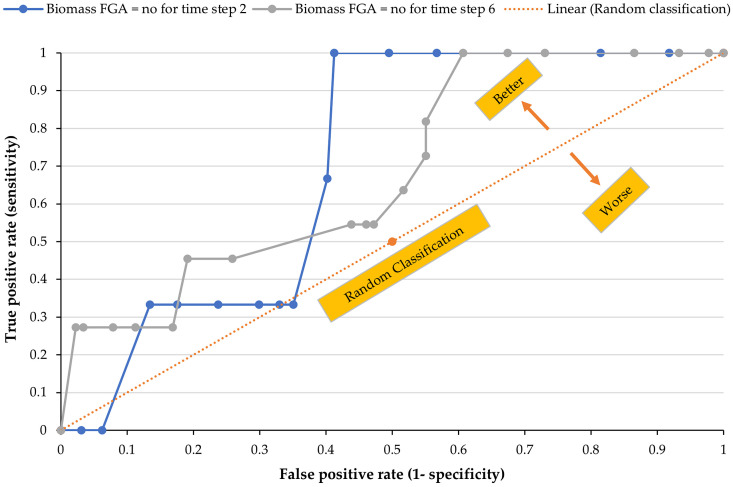

4.1. Model validation

One of the crucial elements in the Bayeasin learning process is model validation. In this section, results of the validation in terms of accuracy and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves are presented and discussed. The accuracy represents the correctness of the model during model validation. It is expressed in terms of probability value or percentage. In this study, the model achieved 0.9466 (94.66%) accuracy to predict the correct value of biomass feedstock gate availability. The interpretation of this result is that the model guessed correctly 852 out of 900 records for all nine time steps in DBN. Accuracy for the individual time steps is drawn in Fig. 13 . Fig. 13 shows that time step 8 has the highest accuracy (1.0 or 100%) while time step 6 has the least accuracy (0.89 or 89%). These results show that the model achieved high accuracy during validation. A graphical relationship between sensitivity2 (true positive rate) and 1-specificity3 (false positive rate) is called the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the ROC curve (AUROC) quantifies the performance of the response variable. The response variable in this analysis is biomass FGA. The ideal value of AUROC is 1, whereas AUROC will have a value of 0.5 for a random guess [73]. This fact indicates that a value above 0.5 and closer to 1 indicates a better judgment, as indicated in Fig. 14 . An increase in AUROC shows high values of true positives, which suggests that model results are accurate.

Fig. 13.

Accuracy of model for each time step.

Fig. 14.

ROC curves for Biomass FGA = no for time steps 2 and 6, representing AUROCs values of 0.7062 and 0.6839, respectively.

The dotted diagonal line in Fig. 14 shows a baseline ROC curve of a hypothetical classifier4 which is worthless and has random classification. Any classifier above the diagonal line is classified as better, while below the diagonal line is worse. It is worth mentioning here that a classifier below a random classification line may have useful information, but the information is being applied incorrectly. Hence, for a model to be validated, the classifier should fall above the diagonal line, and the AUROC should be closer to 1. Being expressed in one number, AUROC shows the quality of the model. Results shown in Fig. 14 (for time steps 2 and 6) indicate that the model offers better performance for both time steps and that results are reliable. The model data has a slightly better quality for time step 2 than time step 6 since the AUROC value for time step 2 (0.7062) is marginally better than the AUROC value for time step 6 (0.6839).

4.2. Practical implications of this study

This study's results can help develop a sustainable and robust biomass supply chain to mitigate the effects of COVID-19. The study can help decision-makers to better plan and cost optimize biofuel production in post-coronavirus conditions. As suggested by this study, one of the significant risk factors in the biomass supply chain is the high transportation cost to move biomass from its origin to the bioprocessing facility. This study finds challenges in selecting an appropriate biorefinery where the presented model could be applied. For this purpose, Mahoney Environmental® is chosen in this study. This company has been a leader in recycling used cooking oils in the U.S. for over 65 years. Furthermore, selecting appropriate bioconversion technology to convert biomass feedstock into biofuel is crucial for developing a sustainable and resilient biomass supply chain. The selection can be made based on the techno-economic studies of the bioconversion process.

Future perspectives of this study are that it provides a risk assessment framework for decision-makers to understand the risk to the biomass supply chain in the post-COVID era when the biofuel industries will emerge as more crucial and critical than ever before. This work finds its applications in developing robust risk management strategies that will help minimize the risk of COVID-19 to the biomass supply chain and ensure the sustainability of the bioeconomy. Moreover, such a design will redefine the role of emerging biofuel industries in the global economy. The results of this research are essential to developing contingency plans to combat the vulnerabilities to the biomass supply chain due to the coronavirus or similar future pandemics. Due to mobility restrictions, the pandemic has caused various socio-economic crises. Such crises have reshaped the investment in renewable and sustainable energy resources, and significant disruption and delays have been witnessed, which have created uncertainty in the production and sustainability of biofuel for years to come. The economic crisis may include fewer employment opportunities in the biofuel sector, closures or limited biomass processing sites, cheaper availability of conventional fossil fuel than biofuel, and lower or limited household incomes due to the pandemic. Socio-crises of the pandemic associated with the biomass supply chain may include discrimination in assigning shift work, especially for hourly waged workers, job layoffs without considering seniority, and an increase in inequality. This research can help deal with socio-economic challenges by providing better resource allocation and sustainable resource management during the pandemic and post-coronavirus situations. The model-building process in this research also faced challenges of identifying risk categories for this study. This challenge is overcome by using expert elicitation and relevant literature. For future work, it is recommended to develop U.S. biofuel policies in light of this study, considering the pandemic challenges. It is also recommended to look at how COVID-19 variants can affect the presented model– a recent variant has been detected in March 2021 named B.1.617.2 (Delta), initially originating in India in December 2020 [74].

5. Conclusions and future work

COVID-19 has hit the whole world and has affected various industries, including the biomass supply chain. The COVID-19 outbreak has significant repercussions for the sustainability of the biofuel industry. As COVID-19 is new, adequate risk management strategies are essential to ensure the sustainability of the biomass supply chain. Although the biofuel industry is nascent in this crucial time, the performance of the biomass supply chain has become more critical. In this study, a risk-based dynamic Bayesian network (DBN) model is presented to assess the biomass supply chain's risk over ten years. Biomass supply chain risk is defined as the unavailability of biomass feedstock to produce biofuel. Dealing with such risk is vital since an uninterpreted continuous supply of the biomass supply chain will guarantee the optimal production of biofuel. The presented model is applied to a U.S. biofuel company. The results indicate that the pandemic has affected the supply chain of biomass, and there are 85.01% chances that the biomass collected in a pandemic will be of low quality. With the development of vaccinations and partial reopening of businesses, this chance falls to 54.23%. Results also indicate that low-quality biomass increases the preprocessing cost of biomass feedstock to 84.60% during the pandemic. Study shows that due to lockdown and lower demand of fossil-based oil, fuel prices would drop to 89% of the regular prices. The dynamic nature of the model indicates a gradual increase in prices and demand for fossil fuels. Results show that the fuel prices will not reach a pre-coronavirus situation, even after nine years of businesses' reopenings. Biomass FGA is low at the start of the pandemic, with the unavailability of 98%. However, vaccination availability helps to drop this unavailability to 7.9% in year two and then there is a gradual decrease in its value.

The presented model is validated using k-fold cross-validation. The ROC curves drawn indicate that the data used in this study are not random guesses and have an accuracy of 95% for all time steps. Measuring risk to the biomass supply chain in this study helps assess the biorefinery’s “riskiness” concerning the risk of fuel market prices. Since COVID-19 is new and the biofuel industries have never seen its impact in the past, the risk data aresparse, and therefore expert elicitation was used in this study. The results of this study can help biofuel investors, managers, and biofuel policy-makers to make well-informed decisions on the sustainability of the biomass supply chain in the post-coronavirus situation. In conclusion, COVID-19 is causing the performance of the biomass supply chain to plummet and is presenting challenges to the sustainability of the biomass supply chain and biorefineries. Nevertheless, coordination at a global level can help to curb COVID-19 impacts and bolster the world’s bioeconomies.

Credit author statement

Zaman Sajid: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank three anonymous professors at the University of Pittsburgh, USA, who provided valuable comments to improve the contents of this work. The author would also like to thank anonymous reviewers and the editorial team for their comments and suggestions to improve this work.

Footnotes

Evidence.

Sensitivity assesses the model’s capability to predict true (correct) positive values. Mathematically, Sensitivity = (true positives/(true positives + false negatives)).

Specificity evaluates the ability of a model to predict true (correct) negative values. Mathematically, Specificity = (true negatives/(true negatives + false positives)).

Each point on a ROC curve is called a classifier.

References

- 1.Mayo C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - symptoms and causes - mayo clinic. 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963

- 2.WHO . World Heal Organ; 2020. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.CSSE . Johns Hopkins Univ; 2020. Coronavirus COVID-19 (2019-nCoV)https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 [Google Scholar]

- 4.ECDC Q., COVID-19 A on. Eur Cent Dis Prev Control. 2020 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/questions-answers [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHOHT . 2020. Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19) - how does COVID-19 spread? Heal Top.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad M. 2020. Coronavirus: how much more time are people spending at home? | News | Al Jazeera.https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/coronavirus-world-staying-home-200406122943899.html [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myllyvirta L. Analysis: coronavirus temporarily reduced China's CO2 emissions by a quarter. Carbon Br. 2020 https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has-temporarily-reduced-chinas-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter [Google Scholar]

- 8.UN D.E.S.A. United Nation Dep Econ Soc Aff; 2020. The social impact of COVID-19 | DISD.https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/2020/04/social-impact-of-covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal S., Gerstel D. The global economic impacts of COVID-19 | center for strategic and international studies. Cent Strateg Int Stud. 2020 https://www.csis.org/analysis/global-economic-impacts-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd J. Institute for Supply Management ® study reveals virus’ supply chain effects. Tempe; USA: 2020. COVID-19 Survey: impacts on global supply chain. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forestry B. Covid-19 Biomass supply chain response - Usewoodfuel. Usewoodfuel Scotl. 2020 https://usewoodfuel.co.uk/covid-19-biomass-supply-chain-response/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright H. Biomass Mag; 2020. Survey: COVID-19 impacts raw material availability for pellets | Biomassmagazine.com.http://biomassmagazine.com/articles/17056/survey-covid-19-impacts-raw-material-availability-for-pellets [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bairamzadeh S., Pishvaee M.S., Saidi-Mehrabad M. Multiobjective robust possibilistic programming approach to sustainable bioethanol supply chain design under multiple uncertainties. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2016;55:237–256. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b02875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold S., Seuring S. Supply chain and logistics issues of bio-energy production. J Clean Prod. 2011;19:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong B.H., How B.S., Lam H.L. Overview of sustainable biomass supply chain: from concept to modelling. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2016;18:2173–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iakovou E., Karagiannidis A., Vlachos D., Toka A., Malamakis A. Waste biomass-to-energy supply chain management: a critical synthesis. Waste Manag. 2010;30:1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundaram S. Biorefineries and chemical processes: design, integration and sustainability analysis. Green Process Synth. 2015;4:65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sajid Z., Zhang Y., Khan F. Process design and probabilistic economic risk analysis of bio-diesel production. Sustain Prod Consum. 2016;5:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2015.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozano-Moreno J.A., Maréchal F. Biomass logistics and environmental impact modelling for sugar-ethanol production. J Clean Prod. 2019;210:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konkol D., Górniak W., Świniarska M., Korczyński M. Springer; 2018. Algae biomass in animal production. Algae biomass charact. Appl; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiaramonti D., Prussi M., Ferrero S., Oriani L., Ottonello P., Torre P., et al. Review of pretreatment processes for lignocellulosic ethanol production, and development of an innovative method. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;46:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mood S.H., Golfeshan A.H., Tabatabaei M., Jouzani G.S., Najafi G.H., Gholami M., et al. Lignocellulosic biomass to bioethanol, a comprehensive review with a focus on pretreatment. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2013;27:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang K., Pei Z., Wang D. Organic solvent pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and biochemicals: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2016;199:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams P., Bridgwater T., Lea-Langton A., Ross A., Watson I. Thornley P, adams PBT-GGB of BS. Academic Press; 2018. Chapter 8 - biomass conversion technologies; pp. 107–139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sajid Z., Khan F., Zhang Y. Process simulation and life cycle analysis of biodiesel production. Renew Energy. 2016;85 doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2015.07.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadhwani N., Liu Z., Eden M.R., Adhikari S. In: Kraslawski A., Turunen I., 23rd, editors. vol. 32. Elsevier; 2013. Simulation, analysis, and assessment of CO2 enhanced biomass gasification; pp. 421–426. (Eur. Symp. Comput. Aided process eng.). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautam P., Kumar S., Lokhandwala S. In: Curr. Dev. Biotechnol. Bioeng. Kumar S., Kumar R., Pandey A., editors. Elsevier; 2019. Chapter 11 - energy-aware intelligence in megacities; pp. 211–238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadokonstantakis S., Johnsson F. 2017. Biomass conversion technologies - D3.1 Report on definition of parameters for defining biomass conversion technologies. Gothenburg. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandey A., Mohan S.V., Chang J.-S., Hallenbeck P.C., Larroche C. Biohydrogen. Elsevier; 2019. Biomass, biofuels, biochemicals. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leduc S., Schwab D., Dotzauer E., Schmid E., Obersteiner M. Optimal location of wood gasification plants for methanol production with heat recovery. Int J Energy Res. 2008;32:1080–1091. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekşioğlu S.D., Acharya A., Leightley L.E., Arora S. Analyzing the design and management of biomass-to-biorefinery supply chain. Comput Ind Eng. 2009;57:1342–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giarola S., Bezzo F., Shah N. A risk management approach to the economic and environmental strategic design of ethanol supply chains. Biomass Bioenergy. 2013;58:31–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shabani N., Sowlati T. A hybrid multi-stage stochastic programming-robust optimization model for maximizing the supply chain of a forest-based biomass power plant considering uncertainties. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:3285–3293. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojha R., Ghadge A., Tiwari M.K., Bititci U.S. Bayesian network modelling for supply chain risk propagation. Int J Prod Res. 2018;56:5795–5819. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma B., Clark R., Hilliard M.R., Webb E.G. Simulation modeling for reliable biomass supply chain design under operational disruptions. Front Energy Res. 2018;6:100. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mousavi Ahranjani P., Ghaderi S.F., Azadeh A., Babazadeh R. Robust design of a sustainable and resilient bioethanol supply chain under operational and disruption risks. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2020;22:119–151. doi: 10.1007/s10098-019-01773-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mamun S., Hansen J.K., Roni M.S. Supply, operational, and market risk reduction opportunities: managing risk at a cellulosic biorefinery. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2020;121:109677. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.109677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen T.D., Jensen F.V. Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. Bayesian networks and decision graphs. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang H., Ganeshbabu U., Thorne T. A dynamic Bayesian network approach for analysing topic-sentiment evolution. IEEE Access. 2020;8:54164–54174. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy K.P. Dynamic bayesian networks. Probabilistic Graph Model M Jordan. 2002;7:431. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benhamou E., Atif J., Laraki R. 2018. A new approach to learning in Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBNs) ArXiv Prepr ArXiv181209027. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kocian A., Massa D., Cannazzaro S., Incrocci L., Di Lonardo S., Milazzo P., et al. Dynamic Bayesian network for crop growth prediction in greenhouses. Comput Electron Agric. 2020;169:105167. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2019.105167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai B., Liu Y., Liu Z., Chang Y., Jiang L. Springer; 2020. A multiphase dynamic bayesian network methodology for the determination of safety integrity levels. Bayesian networks reliab. Eng; pp. 217–237. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramírez P.A.P., Utne I.B. Use of dynamic Bayesian networks for life extension assessment of ageing systems. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2015;133:119–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2014.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li M., Liu Z., Li X., Liu Y. Dynamic risk assessment in healthcare based on Bayesian approach. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2019;189:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2019.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christopher M., Peck H. 2004. Building the resilient supply chain. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sajid Z., Khan F., Zhang Y. Integration of interpretive structural modelling with Bayesian network for biodiesel performance analysis. Renew Energy. 2017;107 doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.01.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amundson J., Faulkner W., Sukumara S., Seay J., Badurdeen F. Bogle IDL, fairweather MBT-CACE. vol. 30. Elsevier; 2012. A bayesian network-based approach for risk modeling to aid in development of sustainable biomass supply chains; pp. 152–156. (22 Eur. Symp. Comput. Aided process Eng.). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rauch P. Developing and evaluating strategies to overcome biomass supply risks. Renew Energy. 2017;103:561–569. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2016.11.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sajid Z., Khan F., Zhang Y. A novel process economics risk model applied to a biodiesel production system. Renew Energy. 2018;118:615–626. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams P.R.D., Inman D., Aden A., Heath G.A. Environmental and sustainability factors associated with next-generation biofuels in the US: what do we know? Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:4763–4775. doi: 10.1021/es900250d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y., Hu Q., Xiao D., Liu X., Shen Y. In: L. Alloc. Biomass crop. Challenges oppor. With chang. L. Use. Li R., Monti A., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2018. Spatial-temporal change of agricultural biomass and carbon capture capability in the mid-south of hebei province; pp. 159–187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ayyub B.M. CRC Press; 2001. Elicitation of expert opinions for uncertainty and risks. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larkin P., Gracie R., Shafiei A., Dusseault M., Sarkarfarshi M., Aspinall W., et al. Uncertainty in risk issues for carbon capture and geological storage: findings from structured expert elicitation. Int J Risk Assess Manag. 2019;22:429–463. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemming V., Burgman M.A., Hanea A.M., McBride M.F., Wintle B.C. A practical guide to structured expert elicitation using the IDEA protocol. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt O., Gambhir A., Staffell I., Hawkes A., Nelson J., Few S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: an expert elicitation study. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:30470–30492. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arlot S., Celisse A. A survey of cross-validation procedures for model selection. Stat Surv. 2010;4:40–79. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Govindarajan M. Text mining technique for data mining application. Proc world Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2007;26:544–549. Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geroldinger A., Lusa L., Nold M., Heinze G. 2021. On resampling methods for model assessment in penalized and unpenalized logistic regression. ArXiv Prepr ArXiv210107640. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marcot B.G., Hanea A.M. What is an optimal value of k in k-fold cross-validation in discrete Bayesian network analysis? Comput Stat. 2020:1–23. [Google Scholar]