Abstract

Although insufficient sleep is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, evidence of a causal relationship is lacking. We investigated the effects of prolonged sleep restriction on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure (BP) and other cardiovascular measures in twenty healthy young participants (aged 23.4±4.8 years, 9 females), who underwent a randomized, controlled, crossover, 16-day inpatient study consisting of 4-days of acclimation, 9 days of sleep restriction (4 hours of sleep/night) or control sleep (9 hours), and 3 days of recovery. Subjects consumed a weight maintenance diet with controlled nutrient composition throughout. 24-hour BP (primary outcome) and cardiovascular biomarkers were measured repeatedly. Polysomnographic monitoring was continuous. Comparing sleep restriction vs control sleep, 24-hour mean BP was higher (adjusted mean difference, Day 12: 2.1 mmHg [95% CI 0.6, 3.6], corrected p=0.016), endothelial function was attenuated (p<0.001), and plasma norepinephrine increased (p=0.011). Despite increased deep sleep, BP was elevated while asleep during sleep restriction and recovery. Post-hoc analysis revealed that 24-hour BP, wakefulness and sleep BP increased during experimental and recovery phases of sleep restriction only in women, in whom 24-hour and sleep systolic BP increased by 8.0 (5.1, 10.8) and 11.3 (5.9, 16.7) mmHg, respectively (both p<0.001). Shortened sleep causes persistent elevation in 24-hour and sleep-time BP. Pressor effects are evident despite closely controlled food intake and weight, suggesting that they are primarily driven by the shortened sleep duration. BP increases are especially striking and sustained in women, possibly suggesting lack of adaptation to sleep loss and thus greater vulnerability to its adverse cardiovascular effects.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, sex disparities, sleep, sleep restriction

Summary

This study shows that experimental sleep restriction causes elevation in ambulatory blood pressure and activation of multiple cardiovascular disease mechanisms, with women exhibiting greater pressor responses and thus vulnerability to insufficient sleep.

Introduction

Over the past half century, sleep habits have changed dramatically. Augmented artificial lighting, shift and night work schedules, access to 24-hour services and the recent ubiquitous use of electronic entertainment and communication technology are thought to contribute to shortening habitual sleep duration. Currently, 35% of the US adult population (equivalent to 80 million people) report sleeping 6 or less hours.1 Similar trends are reported in other Western societies,2 speaking to the global scale of this phenomenon. The repercussions of chronic sleep deficiency for morbidity and mortality risk are increasingly recognized. Epidemiological and community-based data strongly suggest that short sleep duration predisposes to cardiovascular (CV) disease3 and especially to hypertension, with those sleeping ≤6 hours having 13-31% greater risk of developing future hypertension relative to those sleeping 7-8 hours.4-7 Notably, the risk of hypertension associated with short sleep appears to be modified by sex and age, with women and younger individuals exhibiting heightened susceptibility.4, 5, 8 Despite convincing observational data, experimental evidence of a causal relationship between chronic sleep deficiency and blood pressure (BP) elevation is lacking. Acute increases in BP occur in response to short periods (24-88 hours) of total sleep deprivation.9-11 However, most of the studies investigating BP changes during prolonged exposure to partial sleep deprivation (namely sleep restriction) - an experimental model that mimics the low-grade cumulative sleep loss experienced in real life - have reported more ambiguous findings,11-17 yielding, in aggregate, no evidence that sleep restriction raises BP.18 It is relevant that in nearly all studies BP assessment was limited to only resting BP readings, and samples were often restricted to men.12, 14, 15

With this study we sought to evaluate the effects of experimentally-induced prolonged sleep restriction on 24-hour ambulatory BP in healthy young adults. We also examined biological mechanisms that may mediate changes in BP and be independently suggestive of CV damage induced by cumulative sleep restriction. Post-hoc analyses were conducted to assess whether the impact of experimental sleep loss on CV function varied by sex.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This was a randomized, controlled, crossover study comparing sleep restriction vs control sleep in a 16-day, inpatient setting. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01433315).

Participants

Participants were recruited by word of mouth, and through advertisements posted on Mayo Clinic websites and clinicaltrials.gov. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18-40 years, body mass index 18.5-35 kg/m2, absence of overt medical or psychiatric diseases, on no medications other than oral contraceptives or intrauterine devices for birth control for women or second generation antihistamines, and history of normal sleep (sleep duration of 7-8 hours/ night and no daytime naps). We excluded those who were pregnant or lactating, night shift-workers, and those who reported tobacco use, excessive alcohol or caffeine intake, and/or sleep disturbances. Eligibility was preliminarily determined by phone interview and confirmed during an overnight visit in the Clinical Research and Trial Unit at Saint Marys Campus Mayo Clinic Hospital. Complete list of screening procedures is provided in the Data Supplement.19

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study and written consent was obtained from all subjects, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomization and masking

Participants were randomized 1:1 into the first period to either sleep restriction or control sleep, and a >3 month washout was allowed between study periods. Sequence order of the crossover design was obtained using a computer-generated random list stratified by sex. Randomization was allocated to participants by study staff. Due to the behavioral nature of the intervention, blinding was not possible for participants. Investigators were masked to group assignment during data processing and analysis.

Procedures

Within one month of the screening visit, participants were admitted to the research unit for 16 consecutive days/15 nights (Figure 1). Each 16-day inpatient study period began with a 4 day/3 night acclimation phase for determination of baseline measures. Participants then underwent a 9 day/9 night experimental phase, followed by 3 days/3 nights for recovery. In both periods, participants were provided 9 hours of time in bed (22:00-7:00) during acclimation and recovery study segments. During the control study period, this bedtime schedule was applied throughout the entire 16-day period. During the 9 day/9 night experimental sleep restriction phase, time in bed was limited to 4 hours (00:30-4:30). This strategy of sleep restriction (i.e., truncation of both sleep onset and sleep offset) was designed to preserve the sleep midpoint and to minimize circadian disruption. Throughout each 16-day period, participants were instrumented with a portable polysomnography (PSG) system for continuous sleep/wakefulness monitoring. A weight maintenance diet with controlled nutrient composition20 was fed to the subjects during inpatient stays (see the Data Supplement for additional information on inpatient study setting).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the inpatient study protocol. Illustration of study phases and scheduled times in bed for control sleep and sleep restriction conditions. Each participant underwent both study conditions in randomized order, after a wash-out period of 3 to 12 months. Initial 4 days/3 nights of acclimation (Days 1-4) were followed by a 9 day/9 night experimental phase (Days 5-13) and a subsequent 3 day/3 night recovery segment (Days 14-16). Blue bars represent 9 hours of time in bed (from 22:00 to 7:00). Red bar represents 4 hours of time in bed (from 12:30 to 4:30).

Outcome assessment

Outcomes were assessed serially throughout each study period to capture trajectories of responses (Table S1). To account for circadian influences, repeated measurements were conducted at the same time of the day. The primary outcome was 24-hour mean arterial pressure (MAP) at the end of the experimental phase (Day 12) in the sleep restriction compared to control sleep. Secondary outcomes included 24-hour MAP and the following outcomes across all experimental and recovery time points: ambulatory BP-derived variables (systolic BP [SBP], diastolic BP [DBP], heart rate) measured as 24-hour and as time-weighted averages, and during comparable wakefulness (i.e., from 7:00 to 22:00) and sleep times (i.e., from 00:30 to 4:3021); endothelial function assessed in the morning by ultrasound as flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD) in response to reactive hyperemia and non-FMD following sublingual nitroglycerin; baroreflex function (sensitivity and effectiveness indexes22, 23 estimated by sequence method) and BP variability (by spectral analysis24, 25) measured during spontaneous breathing in the evening; and morning levels of circulating norepinephrine, endothelin-1, and vasopressin. Although not prespecified endpoints, PSG indexes26 were evaluated to characterize the nature of the sleep manipulation. Detailed methods of outcome assessment are supplied in the Data Supplement.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics are presented as mean (SD) and number (percentage). Absolute differences between conditions in primary and secondary outcomes were evaluated using longitudinal mixed models that account for missingness, with participant as a random effect and order of the randomization sequence, period, baseline (acclimation), sex, condition (sleep restriction vs control sleep), day, and interaction condition by day as fixed effects. An autoregressive 1 covariance structure was used to model covariation between repeated measures. Holms-Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. Post-hoc analysis investigating the effect of sex was conducted in a similar manner, in male and female participants separately. Adjusted estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI, not adjusted for multiplicity) are presented for each endpoint, together with uncorrected and corrected p-values. Although carryover was not anticipated due to extended interval between study periods, its potential effects were tested as condition by visit and found to be nonsignificant, hence removed from analysis. SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis, with a 2-sided p value <0.05 defined as the level of significance.

Results

Twenty participants (11 males, 23.4±4.8 years, body mass index 24.5±3.5 kg/m2) were randomized and completed both study periods. Characteristics of participants assigned to control sleep first (n=11) and to sleep restriction first (n=9) were similar at study entry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristic | All (N=20) | Control Sleep First (n=11) | Sleep Restriction First (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 23.4 (4.8) | 23.5 (3.8) | 23.2 (6.1) |

| Male, n | 11 (55) | 6 (55) | 5 (56) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.5 (3.5) | 24.7 (3.3) | 24.3 (4.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 15 (75) | 7 (64) | 8 (89) |

| Black/African-American | 2 (10) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Other* | 3 (15) | 2 (18) | 1 (11) |

| Contraceptive use, n | 6 (67) | 2 (40) | 4 (100) |

| Caffeine consumption, cups/day | 1 (1) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.8 (1.5) |

| Alcohol consumption, drinks/week | 1 (2) | 0.7 (1.1) | 1.6 (2.9) |

| Habitual sleep duration, h | 8 (1) | 7.9 (0.8) | 7.7 (1.2) |

| Apnea-hypopnea index, event/h | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.6 (0.4) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 2.8 (3.2) | 1.4 (1.5) | 4.6 (3.8) |

Data are expressed as mean (SD) and number (percentage).

One mixed race Native American/White, one mixed race African-American/White, one mixed race Hispanic/White.

24-hour MAP at Day 12 was significantly increased during experimental sleep restriction relative to control sleep (adjusted mean difference at Day 12: 2.1 mmHg [95% CI 0.6, 3.6], corrected p=0.016; Table 2). There was an overall significant condition effect on 24-hour MAP (p<0.001), and evaluation of time course of changes showed that MAP increases were maximal at the beginning of sleep restriction (Day 6) and returned to baseline values during recovery. Similar trajectories were seen for 24-hour SBP (overall condition effect: p=0.001; Day 12: 3.1 mmHg [0.9, 5.3], corrected p=0.012; Figure 2) and 24-hour DBP (overall condition effect: p<0.001; Day 12: 2.2 mmHg [0.7, 3.7], corrected p=0.010; Table 2), though the magnitude of increases was greater for SBP than DBP. Conversely, 24-hour heart rate did not vary between conditions. Sensitivity analysis using time-weighted 24-hour BP values showed similar results to conventional averages (Table S2).

Table 2.

Mixed model comparisons between control sleep and sleep restriction on primary and secondary outcomes.

| P-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Control Sleep Mean (SD) | Sleep Restriction Mean (SD) | Adjusted Between-group difference (95% CI) | Overall | Day | Holms-Bonferroni corrected P-value |

| 24-hour ambulatory BP | ||||||

| MAP, mmHg | <0.001 | |||||

| Day 3 | 85.3 (5.8) | 84.3 (4.8) | ||||

| Day 6 | 82.6 (5.1) | 85.8 (5.1) | 3.8 (2.3, 5.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 9 | 81.8 (4.5) | 84.6 (5.1) | 3.2 (1.7, 4.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 12 | 83.1 (4.3) | 84.8 (4.8) | 2.1 (0.6, 3.6) | 0.008 | 0.016 | |

| Day 15 | 83.0 (5.3) | 82.2 (4.7) | −0.1 (−1.6, 1.4) | 0.892 | 0.892 | |

| SBP, mmHg | 0.001 | |||||

| Day 3 | 118.2 (8.4) | 116.3 (7.3) | ||||

| Day 6 | 115.8 (8.0) | 119.0 (7.2) | 4.2 (2.1, 6.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 9 | 114.5 (7.5) | 117.8 (7.8) | 4.2 (2.0, 6.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 12 | 115.9 (7.8) | 117.3 (7.3) | 3.1 (0.9, 5.3) | 0.006 | 0.012 | |

| Day 15 | 115.2 (8.3) | 115.1 (6.4) | 1.2 (−1.0, 3.3) | 0.280 | 0.280 | |

| DBP, mmHg | <0.001 | |||||

| Day 3 | 69.0 (6.0) | 68.0 (5.3) | ||||

| Day 6 | 66.2 (5.7) | 69.5 (5.9) | 3.9 (2.4, 5.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 9 | 65.7 (5.0) | 68.3 (5.8) | 3.2 (1.8, 4.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Day 12 | 66.7 (5.0) | 68.6 (5.6) | 2.2 (0.7, 3.7) | 0.005 | 0.010 | |

| Day 15 | 66.6 (5.6) | 65.9 (5.7) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.3) | 0.805 | 0.805 | |

| Heart rate, bpm | 0.603 | |||||

| Day 3 | 69.1 (7.9) | 69.3 (8.3) | ||||

| Day 6 | 69.5 (7.6) | 71.0 (7.9) | 1.1 (−0.8, 3.0) | 0.261 | 1.000 | |

| Day 9 | 69.6 (7.4) | 70.3 (6.6) | 0.8 (−1.1, 2.7) | 0.421 | 1.000 | |

| Day 12 | 71.4 (8.0) | 72.1 (8.6) | −0.5 (−2.5, 1.6) | 0.650 | 1.000 | |

| Day 15 | 72.8 (7.6) | 72.7 (6.9) | −0.1 (−2.1, 1.9) | 0.918 | 1.000 | |

| Endothelial function * | ||||||

| FMD, % | <0.001 | |||||

| Day 4 | 8.8 (3.6) | 9.6 (3.9) | ||||

| Day 7 | 8.4 (3.6) | 6.7 (4.0) | −1.9 (−3.6, −0.3) | 0.023 | 0.046 | |

| Day 10 | 8.9 (3.8) | 6.9 (2.7) | −2.2 (−3.8, −0.6) | 0.009 | 0.034 | |

| Day 13 | 8.2 (3.9) | 6.2 (3.2) | −2.2 (−3.8, −0.6) | 0.009 | 0.034 | |

| Day 16 | 8.8 (4.8) | 7.5 (4.3) | −1.8 (−3.5,- 0.1) | 0.041 | 0.046 | |

| non-FMD, % | 0.053 | |||||

| Day 4 | 24.4 (6.1) | 24.2 (5.4) | ||||

| Day 7 | 24.5 (6.7) | 22.2 (5.5) | −2.9 (−4.9, −1.0) | 0.003 | 0.012 | |

| Day 10 | 24.4 (6.4) | 23.0 (4.6) | −1.5 (−3.4, 0.4) | 0.118 | 0.355 | |

| Day 13 | 24.2 (6.7) | 24.3 (5.7) | −0.8 (−2.7, 1.1) | 0.419 | 0.839 | |

| Day 16 | 24.1 (6.0) | 24.9 (5.0) | −0.0 (−1.9, 1.9) | 0.993 | 0.993 | |

| Norepinephrine, pg/mL | 0.011 | |||||

| Day 4 | 162.1 (115.0) | 153.1 (57.2) | ||||

| Day 7 | 150.0 (70.6) | 207.7 (126.2) | 55.5 (20.0, 91.0) | 0.003 | 0.011 | |

| Day 10 | 149.5 (77.1) | 190.2 (114.2) | 35.4 (−0.0, 70.9) | 0.050 | 0.101 | |

| Day 13 | 146.2 (75.5) | 189.8 (114.1) | 43.9 (8.4, 79.4) | 0.016 | 0.049 | |

| Day 16 | 137.0 (56.8) | 150.3 (69.5) | 10.1 (−25.3, 45.6) | 0.569 | 0.569 | |

| 24-hour TST, min | <0.001 | |||||

| Days 1-4 | 484.7 (27.7) | 484.5 (38.6) | ||||

| Days 5-7 | 483.9 (23.8) | 245.0 (12.3) | −238.3 (−252.7, −224.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Days 8-10 | 477.7 (23.1) | 255.0 (25.1) | −222.0 (−236.3, −207.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Days 11-13 | 475.8 (28.5) | 263.9 (29.1) | −211.3 (−225.6, −196.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Days 14-15 | 481.7 (25.0) | 545.7 (34.2) | 67.0 (52.5, 81.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Models assessing FMD and non-FMD were further adjusted for pre-FMD and pre-non-FMD values.

BP, blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FMD, flow mediated vasodilation, TST, total sleep time.

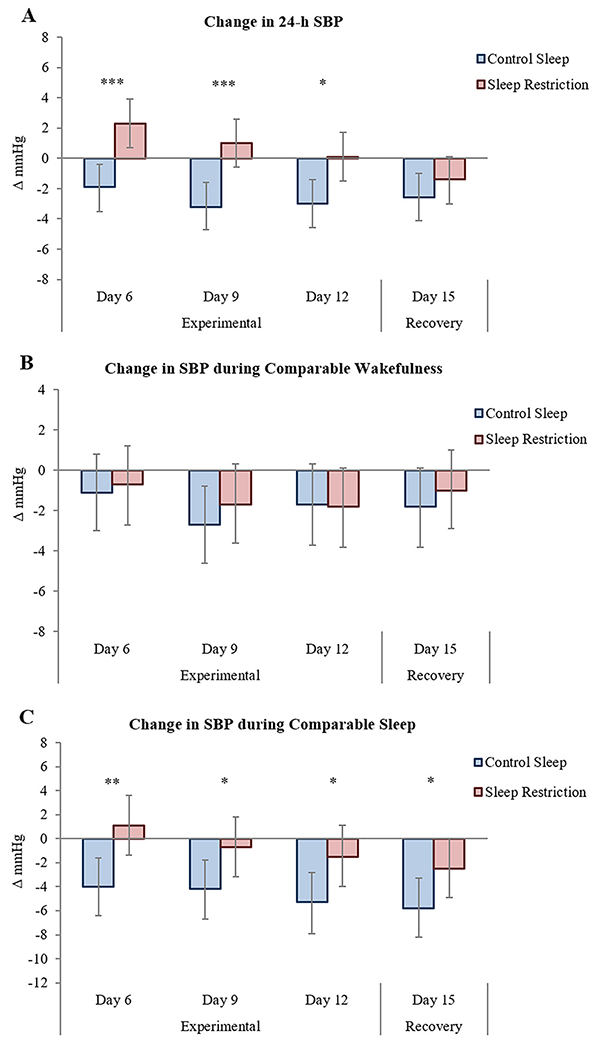

Figure 2.

Adjusted changes from acclimation in 24-hour SBP (A), SBP during comparable wakefulness (B), and SBP during comparable sleep (C) across experimental and recovery time points. Control sleep is depicted in blue and sleep restriction in red. Error bars are 95% CI. Statistical significance for between-group comparisons is reported. * corrected p<0.05, ** corrected p<0.01, *** corrected p<0.001. SBP, systolic blood pressure.

BP values did not vary during comparable wakefulness (when participants were awake in both restricted and control conditions, from 7:00-22:00; Figure 2 and Table S2). On the other hand, there was a main effect of condition for MAP (p=0.009) and SBP (p<0.001) during comparable sleep (when participants were asleep in both restricted and control conditions, from 00:30-4:30), with both being overall higher during experimental sleep restriction vs control sleep. Differences in sleep time SBP became evident during early exposure, persisted throughout the entire experimental sleep curtailment phase (Day 12, 3.9 mmHg [0.8, 6.9], corrected p=0.043), and continued into recovery (Day 15, 3.3 mmHg [0.3, 6.3], corrected p=0.043; Figure 2 and Table S2).

FMD was blunted in response to sleep restriction compared to control sleep (overall p <0.001; Figure 3 and Table 2), with consistent decreases from early exposure throughout the experimental phase (Day 13, −2.2% [−3.8, −0.6], corrected p=0.034). Impaired FMD also persisted into recovery (Day 16, −1.8% [−3.5, −0.1], corrected p=0.046). Endothelial function results were comparable when considering absolute changes, and there were no effects on baseline pre-FMD or baseline pre-non-FMD (Table S3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted changes from acclimation in FMD (A) and plasma norepinephrine (B) across experimental and recovery time points. Control sleep is depicted in blue and sleep restriction in red. Error bars are 95% CI. Statistical significance for between-group comparisons is reported. * corrected p<0.05. FMD, flow-mediated vasodilation.

Plasma norepinephrine increased during sleep restriction relative to control sleep (overall p=0.011; Figure 3 and Table 2), with significant elevation on Day 7 (55.5 pg/mL [20.0, 91.0], corrected p=0.011) and Day 13 (43.9 pg/mL [8.4, 79.4], corrected p=0.049). No changes were found in endothelin-1 or vasopressin (Table S3).

Indices of baroreflex function and BP variability did not vary appreciably during experimentally-induced sleep restriction compared to control sleep (Table S4). Weight was stable throughout the study in both conditions (Table S5).

PSG measures confirmed the intended sleep curtailment throughout the experimental sleep restriction phase vs control sleep (overall p<0.001), with sleep rebound in the recovery phase (Table 2). Sleep metrics during comparable sleep times during the ambulatory BP monitoring nights showed increased sleep efficiency (p=0.017) and duration of N3 sleep stage (p<0.001), along with decreased N1 and N2 sleep stages (both p’s <0.001), in the experimental sleep restriction phase in comparison to control sleep (Table S6).

Post-hoc analysis on sex differences revealed that 24-hour ambulatory BP increased significantly only in women, with increased 24-hour MAP, SBP (Figure 4), and DBP (all p’s for main effect of condition <0.001; Table S7) comparing sleep restriction vs control sleep. Increases were more pronounced during initial experimental phase and were maintained throughout the 9 days of exposure (Day 12, 24-hour MAP: 5.2 mmHg [2.8, 7.6], corrected p<0.001; 24-hour SBP: 8.0 mmHg [5.1, 10.8], corrected p<0.001; 24-hour DBP: 5.0 mmHg [2.4, 7.5], corrected p<0.001). Notably, 24-hour SBP remained elevated between conditions when sleep was reinstated in the recovery phase (Day 15: 4.1 mmHg [1.6, 6.6], corrected p=0.003). In women, BP was overall markedly higher during comparable wakefulness (SBP, p=0.043; DBP, p=0.044) and during comparable sleep (MAP, p=0.006; SBP, p<0.001) in experimental sleep restriction vs control sleep. The sleep time relative elevation in SBP manifested throughout the experimental phase (Day 12: 11.3 mmHg [5.9, 16.7], corrected p<0.001) and was retained into recovery (Day 15: 5.7 mmHg [1.1, 10.2], corrected p=0.016).

Figure 4.

Adjusted between-group differences in 24-hour SBP (A), SBP during comparable wakefulness (B), and SBP during comparable sleep (C) across experimental and recovery time points in women and men separately. Women are depicted in purple and men in green. Error bars are 95% CI. Statistical significance for between-group comparisons within each sex is reported. * corrected p<0.05, ** corrected p<0.01, *** corrected p<0.001. SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Conversely, in men no main effects of condition were evident in any 24-hour BP outcomes (Figure 4 and Table S12). Notably, during comparable wakefulness MAP (p=0.044) and DBP (p=0.040) were overall lower during sleep restriction than during control sleep in men, with these effects more pronounced towards the end of the experimental phase (MAP, Day 12: −3.8 mmHg [−6.4, −1.2], corrected p=0.023; DBP, Day 12: −3.7 mmHg [−6.1, −1.4], corrected p=0.013). There were no significant effects on BP measures during comparable sleep.

Patterns of endothelial function, heart rate, blood biochemistry, BP variability and baroreflex function, along with sleep, were similar in women (Tables S7-S11) and in men (Tables S12-S16) and resembled those seen in the entire sample, although statistical significance was marginal.

Discussion

This study provides direct evidence that prolonged sleep curtailment raises 24-hour and sleep-time BP, and activates several CV disease mechanisms, including impaired endothelial function and sympathetic upregulation, in healthy young adults. These changes occurred in the setting of controlled food intake and stable body weight, suggesting that they are primarily driven by the shortened sleep duration. Importantly, the pressor effect of cumulative sleep loss is potentiated and sustained in women, suggesting sex-dependent susceptibility to sleep debt.

Our primary outcome, 24-hour MAP at Day 12, showed significant elevation during experimental sleep restriction relative to control sleep. Increases in 24-hour MAP manifested early, peaking at the beginning of the exposure, and persisted throughout the 9-day experimental phase. SBP and DBP exhibited comparable profiles, although the magnitude of response was greater for SBP than for DBP. These results indicate that the hypertensive effects of sleep loss emerge early and persist for the duration of the stimulus, reflecting lack of adaptation and showing, for the first time, direct causative data supporting the observations linking habitual short sleep and increased risk of new-onset hypertension.4-8

Previous studies that applied sleep restriction models to simulate real-life conditions of protracted partial sleep curtailment yielded largely null results in terms of any BP effects, despite applying various degrees and duration of sleep truncation.11-16 The approach used to assess BP may be implicated, as in nearly all of these studies BP was determined from resting measures.12, 14-16 While this method captures only single snapshots of resting BP, ambulatory BP monitoring used in the present study tracks BP fluctuations across the 24 hours, thus enabling a comprehensive BP assessment.27 Clinically, it is well recognized that 24-hour ambulatory BP conveys superior and incremental prognostic information compared to office measures, and is a powerful predictor of CV disease and death, irrespective of clinic BP.28, 29 Furthermore, nighttime BP is a more sensitive marker for adverse events and target organ injury than either daytime BP or even 24-hour averages,30-32 with 21% higher mortality conferred by each 10 mmHg elevation in nighttime SBP.33 This is especially relevant as in our study we primarily observed sizeable, persistent relative BP increases during comparable sleep times. However it is deserving of emphasis that there was a sex-specific clear increase even in daytime BP only in women, and not evident in men, as described later. Notably, sleep-time BP elevation manifested despite more consolidated sleep (greater sleep efficiency) and particularly increased deep sleep, which is normally accompanied by lower BP. Our findings are consistent with Yang et al,13 who found, in a parallel-group study design, that repeated exposure to 3 nights of 4 hours of sleep evoked BP increases in 20-hour daily averages, largely due to elevation in nocturnal values. Conversely, St Onge et al17 observed increased wake BP following a home-based sleep restriction intervention, although the unsupervised setting, without diet monitoring, may have confounded these results.

Another element presumably implicated in these discrepant findings pertains to the sample selection, as most of the previous studies included only men.12, 14, 15 Disaggregation of data by sex revealed that, while BP in males was largely unaffected, women experienced a marked and sustained relative increase in 24-hour BP, with an increase in SBP of between 8 to 9 mmHg throughout the experimental period, with no signs of adaptation to cumulative sleep loss. This is further confirmed by evaluation of diurnal BP profile which depicts a distinct pattern of responses, with men exhibiting progressive decreases in BP during wakefulness and no changes during sleep, indicative of homeostatic adjustment, and women showing overall elevation during wakefulness and particularly during sleep. Although this analysis was exploratory, these data strongly suggest a potentiated biological vulnerability to sleep deficiency in women thus providing, for the first time, a deterministic basis for the epidemiological observations of sex-dependent risk of hypertension associated with short sleep.5, 8 Our findings are particularly important given recent observations from pooled cohorts challenging conventional knowledge of BP trajectories in men and women, by showing that BP increases are steeper in women and the divergence ensues at young ages.34 Given its widespread prevalence,1, 2 insufficient sleep may be implicated in such trajectories, compromising the cardioprotection normally exhibited by young women and contributing to their more rapid progression towards hypertension.

Sleep restriction elicited other adverse CV effects, which accompanied and potentially mediated the observed BP changes. Consistent with Dettoni et al,12 norepinephrine increased significantly during experimentally-induced sleep deficiency, reflecting overall sympathetic hyper-activation. As the time course of changes in circulating norepinephrine paralleled that of BP, heightened sympathetic drive is likely an important mediator of BP changes. This hypothesis is further supported by the absence of a counter-regulatory, reflex-mediated decrease in heart rate, along with unchanged baroreflex sensitivity. Short-term BP variability remained unaltered. Another CV disease mechanism activated by restricted sleep was endothelial dysfunction, in line with prior reports.12, 15, 16 FMD, a measure of peripheral endothelial function, was significantly attenuated throughout the experimental sleep curtailment vs control sleep phase. This reflects impaired nitric oxide release, possibly secondary to sympathetic upregulation.35, 36 The cause-effect relationship between endothelial dysfunction and high BP is complex,37 and since the temporal profile of changes in FMD approximated that of BP, interpretation of relative contributory roles is challenging. Regardless, endothelial dysfunction is an established precursor of atherosclerosis and an independent risk factor for future CV events.38, 39 Other mechanisms possibly involved in our findings include systemic inflammation,11 insulin resistance,40, 41 and abnormal sodium reabsorption.13

The inclusion of a recovery period allowed us to determine whether the CV perturbation induced by experimental sleep restriction would reverse upon restoration of normal sleep. While overall 24-hour BP recovered to baseline levels, sleep BP remained elevated during recovery after sleep restriction vs control sleep, along with impaired FMD. Again, a sex patterning emerged in the recovery phase, as BP remained higher both during sleep time and across the 24-hours only in women despite resumption of adequate sleep. These data imply that the CV disruption produced by sleep curtailment may not rapidly resolve when sleep is reinstated, especially in women, and residual effects likely contribute to CV risk and to sleep-related sex disparities. These findings are also relevant in the context of recent research evaluating the health hazards of irregular sleep patterns42 and specifically the implications of the so called “catch-up sleep” during weekends. While observational data point toward a protective function of compensatory sleep during weekends,43, 44 experimental data from our and prior studies15 suggest that short periods of extended sleep opportunity may be insufficient to mitigate the negative effects caused by short sleep during weekdays.

Given the enduring high prevalence of hypertension in the general population45 and the soaring prevalence of insufficient sleep, recognition of the consequences of sleep loss on BP control and overall CV function is critical for population-level health strategies. Short sleep is acknowledged as a cardiometabolic risk factor in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for primary prevention of CV disease,46 and obtaining sufficient sleep is now advocated as a public health priority.47 This may be particularly significant for women’s health, considering the heightened impact of sleep restriction in women and thus its likely role in generating and perpetuating sex disparities in CV disease. Importantly, as short sleep may be largely volitional, resulting from unhealthy sleep habits, sleep debt may be amenable to correction. Interventions aimed at normalizing sleep duration to the recommended healthy range of 7-9 hours a night48, 49 may contribute to facilitate prevention and/or attenuation of hypertension and other adverse sequelae of insufficient sleep, especially in women.

This study capitalizes on the unique strength of continuous PSG monitoring. Our customized, ambulatory system enabled us to obtain precise quantification and characterization of sleep and wakefulness across the 24 hours throughout each 16-day period, thus avoiding the inherent inaccuracies and limitations of behavioral visual monitoring and actigraphy, and confirming a difference in sleep duration of 3.5 to 4 hours/night. Furthermore, our results are not confounded by changes in body weight or diet, as nutritional intake was controlled.

Limitations include the modest sample size that may have reduced our ability to detect effects on secondary outcomes and exploratory analysis. In mitigation, this was a randomized tightly controlled within-subject study, requiring comprehensive screening and study measurements extending over about two months for each participant. As our sample consisted of young subjects without CV disease or known CV risk factors, results may not be generalizable to older adults and or individuals with preexisting vulnerabilities. The hypothesis that the adverse CV effects caused by prolonged sleep restriction may be potentiated in a high-risk population warrants investigation. Moreover, as we did not control for phases of the menstrual cycle, we cannot exclude that hormonal changes may have affected our results in women. However, evidence of hormonal phase-dependent fluctuations in CV activity is conflicting, especially on BP.50-52 In addition, most of our female subjects were taking contraceptives, which would mitigate these effects. Aside from voluntary sleep restriction, sleep duration may be reduced due to the impact of a multitude of sleep disruptors, including light and noise pollution. Despite epidemiological data supporting a linkage between nocturnal noise and light exposure and risk of CV disease, including elevated BP,53-56 the potential mediating role of shortened sleep duration awaits clarification.

Perspectives

Our study shows that prolonged exposure to experimental sleep restriction causes sustained increases in 24-hour and sleep-time BP together with sympathetic activation and vascular dysfunction in healthy young adults. Such effects emerge early, are sustained for the duration of the exposure, are evident despite no changes in nutritional intake or body weight, and only partially dissipate upon restoration of normal sleep. Sex-specific patterns are evident, with potentiated pressor responses to insufficient sleep manifest only in women. Collectively, these data confer causal support for epidemiological observations that short sleep predisposes to hypertension and CV disease. Our findings further suggest that sleep debt may be implicated in sex disparities in cardiovascular risk, and may be particularly important in understanding the steeper trajectory of BP increases seen in women compared to men. Future studies should address whether such responses are exacerbated in individuals with preexisting CV risk factors, and whether therapeutic strategies targeting sleep time have the potential for improving population health.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

Healthy young individuals exposed to prolonged sleep restriction experience increases in 24-hour and sleep BP, together with sympathetic activation and vascular dysfunction

BP increases are especially striking and durable in women

Adverse effects of shortened sleep may persist despite resumption of normal sleep

What is Relevant

Short sleep may contribute to increase risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease

Women may be particularly at risk from the effects of sleep loss

Sources of Funding

The study was funded by NIH RO1 HL 114676 and CTSA grant UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

N.C. is supported by NIH R01 HL 134808, R01 HL 134885, American Heart Association 16SDG27250156, and the Mayo Clinic Marie Ingalls Research Career Development award. V.K.S is supported by NIH R01 HL 134808, R01 HL 134885, and RO1 HL 65176.

Footnotes

Disclosures

V.K.S serves as a consultant for Baker Tilly, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sleep Number and Respicardia. The other authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Liu Y, Wheaton AG, Chapman DP, Cunningham TJ, Lu H, Croft JB. Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults—united states, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Sleep Foundation. 2013 sleep in america poll: International bedroom poll. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, Li S, Huang H, Li P, Peng X, Peng Z, Yu K, Bao W. Relationship of sleep duration with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gangwisch JE, Heymsfield SB, Boden-Albala B, Buijs RM, Kreier F, Pickering TG, Rundle AG, Zammit GK, Malaspina D. Short sleep duration as a risk factor for hypertension - analyses of the first national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2006;47:833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, Miller MA, Taggart FM, Kumari M, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Brunner EJ, Marmot MG. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: The whitehall ii study. Hypertension. 2007;50:693–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knutson KL, Van Cauter E, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Hulley SB, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Association between sleep and blood pressure in midlife: The cardia sleep study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1055–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Mei H, Jiang Y-R, Sun W-Q, Song Y-J, Liu S-J, Jiang F. Relationship between duration of sleep and hypertension in adults: A meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:1047–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Cappuccio FP, Donahue RP, Rafalson LB, Hovey KM, Freudenheim JL, Kandala N-B, Miller MA, Trevisan M. A population-based study of reduced sleep duration and hypertension. The strongest association may be in premenopausal women. J Hypertens. 2010;28:896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato M, Phillips BG, Sigurdsson G, Narkiewicz K, Pesek CA, Somers VK. Effects of sleep deprivation on neural circulatory control. Hypertension. 2000;35:1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter JR, Durocher JJ, Larson RA, DellaValla JP, Yang H. Sympathetic neural responses to 24-hour sleep deprivation in humans: Sex differences. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1991–H1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N, Regan MM, Price NJ, Dinges DF, Mullington JM. Effect of sleep loss on c-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:678–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dettoni JL, Consolim-Colombo FM, Drager LF, Rubira MC, de Souza SBPC, Irigoyen MC, Mostarda C, Borile S, Krieger EM, Moreno H, et al. Cardiovascular effects of partial sleep deprivation in healthy volunteers. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang H, Haack M, Gautam S, Meier-Ewert HK, Mullington JM. Repetitive exposure to shortened sleep leads to blunted sleep-associated blood pressure dipping. J Hypertens. 2017;35:1187–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Leeuwen WM, Sallinen M, Virkkala J, Lindholm H, Hirvonen A, Hublin C, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Härmä M. Physiological and autonomic stress responses after prolonged sleep restriction and subsequent recovery sleep in healthy young men. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2018;16:45–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauvet F, Drogou C, Bougard C, Arnal PJ, Dispersyn G, Bourrilhon C, Rabat A, Van Beers P, Gomez-Merino D, Faraut B, et al. Vascular response to 1 week of sleep restriction in healthy subjects. A metabolic response? Int J Cardiol. 2015;190:246–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvin AD, Covassin N, Kremers WK, Adachi T, Macedo P, Albuquerque FN, Bukartyk J, Davison DE, Levine JA, Singh P, et al. Experimental sleep restriction causes endothelial dysfunction in healthy humans. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St-Onge M-P, Campbell A, Aggarwal B, Taylor JL, Spruill TM, RoyChoudhury A. Mild sleep restriction increases 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure in premenopausal women with no indication of mediation by psychological effects. Am Heart J. 2020;223:12–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu S, Jing S, Gao Y. Sleep restriction effects on bp: Systematic review & meta-analysis of rcts. West J Nurs Res. 2019:0193945919868143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-ii. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris JA, Benedict FG. A biometric study of basal metabolism in man. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth JN, Anstey DE, Bello NA, Jaeger BC, Pugliese DN, Thomas SJ, Deng L, Shikany JM, Lloyd-Jones D, Schwartz JE. Race and sex differences in asleep blood pressure: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (cardia) study. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:184–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernardi L, De Barbieri G, Rosengård-Bärlund M, Mäkinen V-P, Porta C, Groop P-H. New method to measure and improve consistency of baroreflex sensitivity values. Clin Auton Res. 2010;20:353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Rienzo M, Parati G, Castiglioni P, Tordi R, Mancia G, Pedotti A. Baroreflex effectiveness index: An additional measure of baroreflex control of heart rate in daily life. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R744–R751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stauss HM. Identification of blood pressure control mechanisms by power spectral analysis. Clinical and experimental pharmacology and physiology. 2007;34:362–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parati G, Saul JP, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Spectral analysis of blood pressure and heart rate variability in evaluating cardiovascular regulation: A critical appraisal. Hypertension. 1995;25:1276–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Quan SF. The aasm manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: Rules, terminology and technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hermida RC, Smolensky MH, Ayala DE, Portaluppi F. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (abpm) as the reference standard for diagnosis of hypertension and assessment of vascular risk in adults. Chronobiology International 2015;32:1329–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang W-Y, Melgarejo JD, Thijs L, Zhang Z-Y, Boggia J, Wei F-F, Hansen TW, Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Jeppesen J. Association of office and ambulatory blood pressure with mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322:409–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Wei F-F, Thijs L, Boggia J, Asayama K, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Björklund-Bodegård K, Ohkubo T, Jeppesen J. Ambulatory hypertension subtypes and 24-hour systolic and diastolic blood pressure as distinct outcome predictors in 8341 untreated people recruited from 12 populations. Circulation. 2014;130:466–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boggia J, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, Richart T, Ohkubo T, Kuznetsova T, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Prognostic accuracy of day versus night ambulatory blood pressure: A cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:1219–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer DA. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure as predictors of death and cause-specific cardiovascular events in hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuspidi C, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Sala C, Negri F, Grassi G, Mancia G. Nighttime blood pressure and new-onset left ventricular hypertrophy: Findings from the pamela population. Hypertension. 2013;62:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan HQ, Li Y, Thijs L, Hansen TW, Boggia J, Kikuya M, Bjorklund-Bodegard K, Richart T, Ohkubo T, Jeppesen J, et al. Prognostic value of isolated nocturnal hypertension on ambulatory measurement in 8711 individuals from 10 populations. J Hypertens. 2010;28:2036–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ji H, Kim A, Ebinger JE, Niiranen TJ, Claggett BL, Merz CNB, Cheng S. Sex differences in blood pressure trajectories over the life course. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamboa A, Figueroa R, Paranjape SY, Farley G, Diedrich A, Biaggioni I. Autonomic blockade reverses endothelial dysfunction in obesity-associated hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:1004–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hijmering ML, Stroes ES, Olijhoek J, Hutten BA, Blankestijn PJ, Rabelink TJ. Sympathetic activation markedly reduces endothelium-dependent, flow-mediated vasodilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:683–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandes RP. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:924–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ras RT, Streppel MT, Draijer R, Zock PL. Flow-mediated dilation and cardiovascular risk prediction: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gokce N, Keaney JF Jr, Hunter LM, Watkins MT, Menzoian JO, Vita JA. Risk stratification for postoperative cardiovascular events via noninvasive assessment of endothelial function: A prospective study. Circulation. 2002;105:1567–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buxton OM, Pavlova M, Reid EW, Wang W, Simonson DC, Adler GK. Sleep restriction for 1 week reduces insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2010;59:2126–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354:1435–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang T, Mariani S, Redline S. Sleep irregularity and risk of cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:991–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwangbo Y, Kim W-J, Chu MK, Yun C-H, Yang KI. Association between weekend catch-up sleep duration and hypertension in korean adults. Sleep Med. 2013;14:549–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Im H-J, Baek S-H, Chu MK, Yang KI, Kim W-J, Park S-H, Thomas RJ, Yun C-H. Association between weekend catch-up sleep and lower body mass: Population-based study. Sleep. 2017;40:zsx089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Delling FN. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, et al. 2019 acc/aha guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1376–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.US Department of Health Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, Hazen N, Herman J, Katz ES, Kheirandish-Gozal L. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1:40–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson N, Badr M, Belenky G, Bliwise D, Buxton O, Buysse D, Dinges D, Gangwisch J, Grandner M, Kushida C. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the american academy of sleep medicine and sleep research society. Sleep. 2015;38:843–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirshoren N, Tzoran I, Makrienko I, Edoute Y, Plawner MM, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Jacob G. Menstrual cycle effects on the neurohumoral and autonomic nervous systems regulating the cardiovascular system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1569–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minson CT, Halliwill JR, Young TM, Joyner MJ. Influence of the menstrual cycle on sympathetic activity, baroreflex sensitivity, and vascular transduction in young women. Circulation. 2000;101:862–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Middlekauff HR, Park J, Gornbein JA. Lack of effect of ovarian cycle and oral contraceptives on baroreceptor and nonbaroreceptor control of sympathetic nerve activity in healthy women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2560–H2566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jarup L, Babisch W, Houthuijs D, Pershagen G, Katsouyanni K, Cadum E, Dudley M-L, Savigny P, Seiffert I, Swart W. Hypertension and exposure to noise near airports: The hyena study. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116:329–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Münzel T, Schmidt FP, Steven S, Herzog J, Daiber A, Sørensen M. Environmental noise and the cardiovascular system. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:688–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Obayashi K, Saeki K, Iwamoto J, Ikada Y, Kurumatani N. Association between light exposure at night and nighttime blood pressure in the elderly independent of nocturnal urinary melatonin excretion. Chronobiol Int. 2014;31:779–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun S, Cao W, Ge Y, Ran J, Sun F, Zeng Q, Guo M, Huang J, Lee RS-Y, Tian L. Outdoor light at night and risk of coronary heart disease among older adults: A prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:822–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.