Abstract

Objective:

Social support is essential in healthy adjustment to life stressors. This scoping review examines how social support has been conceptualized, operationalized, and studied among siblings of children with cancer. Gaps in the current literature are identified, and future research directions are proposed.

Methods:

A rigorous systematic scoping review framework guided our process. Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Scopus were searched for literature regarding social support and siblings of children with cancer. After screening, 57 articles were identified (n=26 quantitative, n=21 qualitative, and n=10 multi-method) and their content extracted for summarization.

Results:

The majority of studies (n=43, 75.4%) were descriptive; 14 (24.6%) included interventions, and of those, four were experimental. Few studies used a clearly defined theoretical framework, or validated tools to measure social support. Studies explored perceived social support needs of siblings, the provision and availability of formal support through interventions and related outcomes, and informal family social supports. A variety of support types were found to be helpful to siblings in different ways.

Conclusions:

Social support is a prevalent topic in the literature regarding siblings of children with cancer. It is unclear what types of support are most important due to how it has been conceptualized and measured. Despite some methodological limitations, greater levels of social support have been linked to better adaptation among siblings of children with cancer. Future work is warranted to identify the most beneficial types of support for siblings based on their age, developmental stage, and the cancer trajectory.

Keywords: Cancer, Childhood Cancer, Adaptation, Psychological, Neoplasms, Oncology, Psycho-oncology, Review [Scoping], Siblings, Social Support, Social Adjustment

Background

Being a sibling of a child diagnosed with cancer can be a lonely and unsettling experience [1,2]. The attention of nearly everyone in the social world of siblings (e.g., parents, friends) turns toward the medical and support needs of the child with cancer. This pattern occurs in families of approximately 16,000 children diagnosed with cancer each year and can persist given the chronic health issues associated with cancer survivorship [3].

Siblings may experience poor psychosocial adjustment in the context of childhood cancer. Siblings report anxiety and worry about the health of their family members, disruptions to their everyday routines, difficulties concentrating in school, lower quality of life, strong negative emotions, and cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms [4,5]. In an attempt to improve sibling well-being and based on previous sibling research, supportive care for siblings is recommended as a psychosocial standard of care in pediatric oncology [6].

Supportive care can take many forms but generally consists of formal support programs or services provided by hospital systems or community organizations to increase quality of life and assist with coping [6]. Social support is typically a component of these services and has been broadly defined as the provision of assistance, comfort, or resources to individuals to help them cope with stressors [7]. Of course, social support is also garnered informally as well, in relationships with family, friends, and others. Social support has been categorized into several specific types: instrumental; emotional; informational; companionship; and finally, appraisal support. Social support is believed to function as a buffer to stress and a promoter of improved coping and resilience, and it is well established as a key factor in health outcomes and adjustment in children and adolescents [8–10].

Two recent systematic reviews have summarized the literature regarding the adjustment of siblings of children with cancer, demonstrating that they are at risk for psychosocial distress [4,5]. While findings are mixed regarding the specific factors associated with adjustment among siblings of children with cancer, social support appears to be important [1,11–14]. However, the quality and content of the literature regarding the role of social support in the adjustment of siblings has not been closely examined. This scoping review was undertaken to fill that gap in the literature and map the existing research examining formal (supportive care) and informal (e.g., family, peer) social support in the context of sibling adjustment to childhood cancer. To do this, we sought to answer the following questions: 1) How has social support been defined or conceptualized in the sibling literature?; 2) What tools or measures have been used to operationalize social support?; 3) What research questions have been posed, and what are the findings related to social support?; and 4) What limitations and gaps exist in this literature?

Methods

We conducted our scoping review using the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [15], and then further expanded by Peters and The Joanna Briggs Institute [16,17]. Arksey’s five-stage process includes: 1) identifying the research questions; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) selecting studies; 4) charting the data; and 5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. To increase transparency and reproducibility, we followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines for scoping reviews [18]. Agreement across screeners/raters (i.e., Kappa values) was calculated for full-text screening and methodological bias assessments. Statistical Methods included Kappa value calculations and descriptive statistics using SPSS [19].

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they: 1) were empirical published reports; 2) mentioned any form of social support; and 3) reported findings related to siblings of children with cancer, including anyone in a sibling-type relationship (e.g., step-siblings, adoptive siblings). Social support was broadly conceptualized as any resource easily categorized into one of the five main types of social support (instrumental, emotional, informational, companionship or appraisal) using our pre-established definitions of the construct (Table 1).

Table 1.

Author Defined Categories of Social Support

| Support Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Emotional | Expressions of empathy and caring or having someone to talk to about your experiences. |

| Instrumental | Tangible items or services such as transportation, money or help with household chores, homework, and skill building. |

| Informational | The provision of knowledge, recommendations, or advice on how or where to get help. |

| Companionship | The presence or availability of others for social engagement and time together. |

| Validation | A sense of belonging and shared world view, and appraisal or acknowledgement for doing a good job. |

Articles were included if the term social support was used within the publication or if the available quantitative or qualitative data were consistent with the definitions or specified constructs of social support. Social support could be provided by any source (e.g., family, friends, or community). Studies that focused on the support of bereaved siblings or were excluded. We also limited the review to studies published within the last 25 years.

Search Strategy

Information retrieval was conducted by a medical librarian (NS) on August 1, 2019 and updated on December 1, 2020. Our primary database was MEDLINE (Ovid) 1946–2019. The Medline search strategy (see Appendix I) was developed and peer reviewed by library colleagues using PRESS guidelines [20], then reviewed by the research team prior to being translated and applied to Embase (embase.com) 1974 – 2019, CINAHL Complete (Ebscohost) ) 1937–2019, PsycINFO (Ebscohost) 1872–2019, Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest) 1952– 2019, and Cochrane Library (wiley.com) including CENTRAL (wiley.com), and Scopus (scopus.org) 1970–2019.

Screening Methods

Results were imported into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics), and duplicates were removed. For screening and selecting manuscripts, we used the online systematic reviewing platform, Covidence (Covidence.org). Two reviewers (SW & MS) independently screened study titles and abstracts and then remaining full texts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Across screeners, decisions regarding inclusion/exclusion of full-text achieved a Kappa of 0.79. All discrepant reviews were discussed, and consensus was reached using an a priori strategy that included a third reviewer (MA).

Data Quality Assessment

Our original protocol [21] indicated that the Johanna Briggs system would be used for quality assessment. However, upon beginning assessments, our team determined that the quality of the current available literature (i.e., few experimental studies) was better captured using a broader, less detailed, approach. Quality assessments were performed using the QualSyst scoring checklists developed by Kmet et al. for evaluation of internal validity of quantitative and qualitative research [22]. Assessing the quantitative studies’ quality consisted of 14 criteria, while the qualitative studies were assessed using 10 criteria. Multi-method studies were evaluated using both checklists.

Criterion assessment questions were entered into Covidence using a custom assessment tool feature and were rated independently by two reviewers (SW & MS). Discrepancies were reviewed and discussed in team meetings, and a final consensus was reached among all authors. Final Kappa between coders across all studies was 0.95 (0.96 for multi-method, 0.84 for qualitative, and 0.97 for quantitative studies). Each criterion was graded for inclusion in the manuscripts on a 0–2-point scale (0=no, 1=partial, and 2=yes). Total scores were calculated by summing all applicable scores and dividing by the total possible score, giving a summary score between 0–1, with higher scores indicating less risk of bias.

Data Extraction

The team discussed and developed the data extraction form in Microsoft Excel to organize and systematize the extraction of the following data elements: research method; study design; measurement tools; demographics of participants; theoretical frameworks; sources and assessed types of social support; primary and secondary findings; and recommended areas for future sibling supportive research.

Results

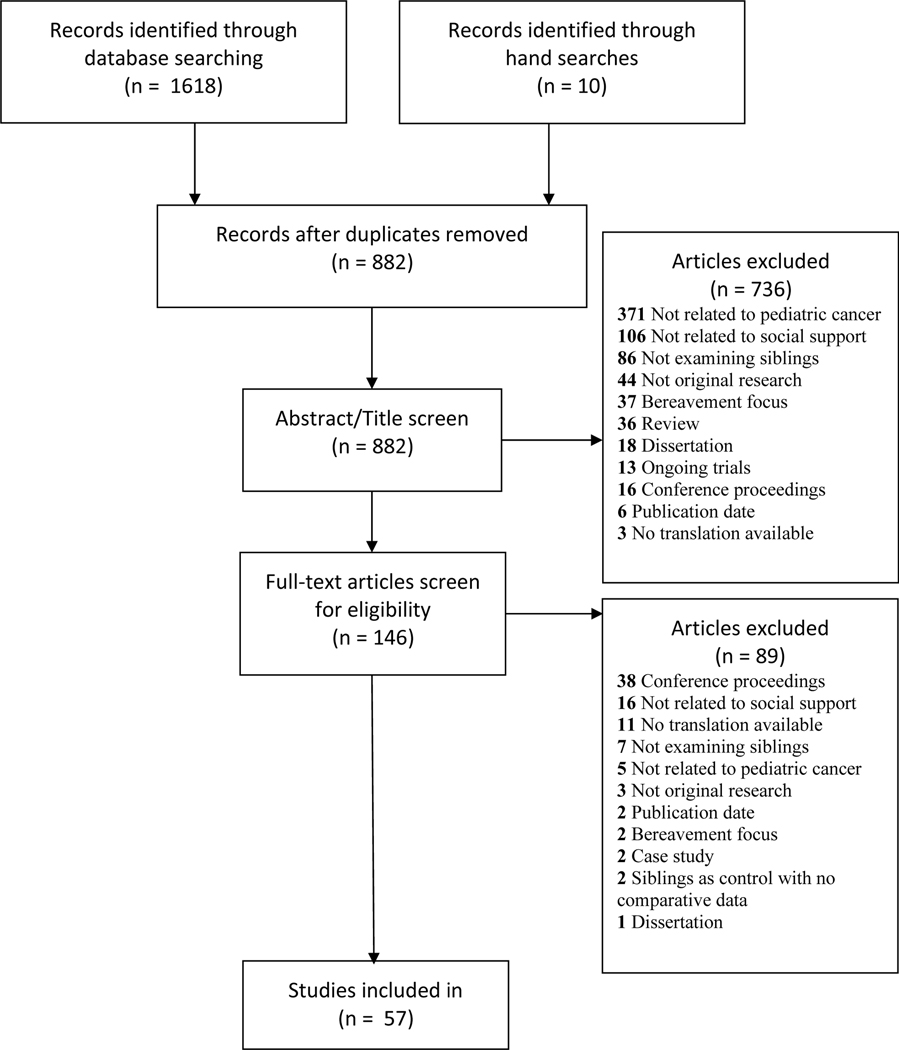

A total of 1618 articles were identified through database searches, 882 of which were unique. An additional ten studies were identified through hand searching reference lists. Abstract and title screening removed 736 non-relevant articles, and full-text review removed an additional 89, resulting in 57 retained studies. Figure 1 provides our PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram.

Overview of Included Studies

Included studies spanned quantitative (45.6%, n=26), qualitative (36.8%, n=21), and multi-method (17.5%, n=10) designs. Methodological elements, sample demographics, and other characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Methodology | Quantitative (N=26) | Qualitative (N=21) | Multi-Method (N=10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | |||

| Cross-sectional | 20 | 19 | 7 |

| Longitudinal | 6 | 2 | 3 |

|

| |||

| Experimental | 2 | 2 | - |

| Quasi-experimental | 5 | - | 1 |

|

| |||

| Respondents | |||

| Sibling | 14 | 10 | 2 |

| Parent | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Multi-Informant | 10 | 8 | 7 |

| Health Care Providers | 1 | 1 | - |

|

| |||

| Sample Size | |||

| 24–184 | 6–202 | 4–74 | |

|

| |||

| Sibling Age | |||

| 3–24yrs | 4–27yrs | 5–25yrs | |

|

| |||

| Time Since Cancer Diagnosis | |||

| Range | 2mo-7yrs | 1mo-18yrs | 6mo-10yrs |

| Unreported in study | 4 | 6 | 4 |

|

| |||

| Study Location | |||

| North America | 16 | 7 | 4 |

| Europe | 6 | 9 | 2 |

| Australia | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Asia | - | 1 | 3 |

| Africa | - | 1 | - |

| Multiple Countries | 3 | - | - |

Most studies (n=43, 75.4%) were descriptive/non-experimental. The remainder, 24.6% (n=14), described interventions: four were randomized trials [23–26]; five were quasi-experimental with a non-randomized sample and comparison group [12,27–30], and five were simple pre-post designs. For more information, a brief summary of each study included in this review is available in Supplement 2.

The quality of the articles ranged from 0.55–1, (M=0.86; SD= 0.11) on a 0–1 scale. Higher scores indicate a lower risk of bias. Within the quantitative studies, lower scores were most commonly related to sampling issues, the use of non-validated measurement tools, and poorly controlled analyses. In qualitative and multi-method studies, lower ratings were typically related to poorly described analyses and lack of verification procedures during coding or in the validation of the conclusions. See Appendices II–IV for detailed quality assessment tables.

Conceptualization of Social Support

Definitions of social support used in the literature varied with relatively few articles offering discrete definitions (n=7, 12.3%). Three focused on the perception of support [11,31,32]. These studies defined social support, similarly, indicating that it was the perception that one is cared for and valued by those in their social network or the perception that such support is available. Two studies used definitions highlighting actual received support [10,33,34].

Ten studies (17.5%) conceptualized social support using a theoretical framework. Of these, two [33,34] used House’s conceptual framework of social support. This framework outlines multiple dimensions of social support as emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal supports. It defines social support as received interpersonal transactions that involve one or more of the above dimensions of social support.

Two studies [35,36] were based on general family-systems theory, conceptualizing the family as a dynamic group of interconnected individuals where the behaviors and circumstances of individual members influence all others. For example, when a child is diagnosed with cancer, the family turns their attention toward that child, resulting in less attention and support for siblings. Similarly, another study [37] used McMaster’s model of family functioning, which assumes that individuals do not react in isolation but according to the organization and behavioral actions of those within their family. This study examined the ways in which stress among parents led to difficulties recognizing the support needs of siblings, and how siblings who sensed parental stress did not seek their support.

Four studies examined social support within a stress and coping model. Two [38,39] used Folkman’s coping model where increased social support was hypothesized to reduce perceived cancer-related stress and to facilitate coping in siblings. Another study examined social support as a component of a peer group-based cognitive behavioral intervention to help siblings reframe their experiences, thus improving their psychosocial health [25]. Similarly, Houtzager et al. [40] conceptualized aspects of social support, namely the provision of information about cancer and instrumental support in developing coping skills, as components of an intervention focused on increasing a sibling’s locus or sense of control and thereby improving wellbeing. Finally, Løkkeberg et al. [41] used a salutogenic model, which demonstrates that confidence in one’s environment or “sense of coherence” allows a person to draw on resources, i.e. social support, in times of stress. In this study, social support among siblings was found to be a factor in helping siblings cope, feel secure, and find meaning in their experience.

The final two studies highlighting a theoretical model used a post-traumatic growth framework [42,43]. Here, social support was conceptualized as actual and perceived appraisal support through shared experience and was hypothesized to promote a positive mental shift after a traumatic event. Such mental shifts were defined as increased value in relationships, compassion, self-esteem, and finding meaning in one’s experiences.

Measurement Tools Utilized and Related Findings

Approximately half of included studies (57%, n=27) used a measurement tool or a qualitative question to specifically examine social support or social support needs. The other half of studies linked their work to social support but measured it indirectly. For example, the impact of camps [28,44–47] or group therapy interventions [24,25,29,32,35,44,48,40,49,46] on adjustment were attributed to aspects of social support even though the construct was indirectly measured.

Six unique, validated tools were used to measure social support in the quantitative studies examined: The Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (CASSS), the Social Support Scale for Children (SSSC), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), the Social Support Satisfaction Scale (SSSS), the Nurse Sibling Social Support Questionnaire (NSSSQ), and the Dubow and Ullmans Social Support Appraisal Scale (Supplement 1). Notably, all but one of these tools examined perceptions of support from specific types of individuals such as parents or peers versus exploring the particular kinds of support given or available to siblings.

The two studies that used the CASSS found peer support was available to siblings and at similar levels to those in comparison groups. Siblings reported teacher support to be as important to them as parental support; however, only parent support was significantly associated with fewer behavioral problems and better school performance [4,12]. Comparably, the two studies using the SSSC indicated that teacher support was high among siblings and was associated with improved emotional functioning [31,1]. One study used the MSPSS and found that perceived social support from all sources was associated with reduced post-traumatic stress symptoms in siblings [43], and the study using the SSSS concluded that greater family’s social support resources resulted in reduced impact of cancer on siblings [36].

The NSSSQ was developed to assess the impact of nurse support among siblings. Results from three studies using this tool indicated that nurses are sources of informational, instrumental, and emotional support [14,27,33]. However, these nursing supports were not found to significantly impact sibling outcomes [14]. The last study using a validated tool used both the Dubow and Ullmans’ Social Support Appraisal Scale and the NSSSQ. This study suggested that higher levels of support were associated with a reduced sense of alienation among siblings [14].

Two additional tools linked to social support but were not designed to specifically measure the construct. Six studies [10,29,35,46,50,51] used the Sibling Perceptions Questionnaire (SPQ). This questionnaire assesses the perceived influence that cancer has had on siblings and includes a subdomain of interpersonal impacts. Several questions within the interpersonal subdomain evaluate the availability of parents for emotional support and changes in companionship of parents and siblings which was found to be meaningful in relation to sibling outcomes in several studies [29,35,46,50,51]. Additionally, a second SPQ subscale, communication, demonstrated in one study [43] that greater communication was significantly associated with lower scores in behavioral problems, depression, and anxiety.

Finally, two studies [51,52] used the Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument (SCNI). Subscales for this tool include information, practical assistance, recreation, feelings, support, understanding, and sibling relationships. These subscales directly link to the five types of social support commonly identified in the literature. Studies using this tool reported that higher levels of unmet needs among adolescent siblings correlated with increased distress.

Research Questions and Findings Related to Social Support

Social support emerged in the literature regarding siblings of children with cancer within three types of studies including those examining: 1) the experiences and needs of siblings, 2) the provision and availability of support from formal supportive care programs, and 3) analysis of informal and family support. Studies in each of these categories are summarized below.

The experiences and perceived needs of siblings

All of the qualitative studies in this review included at least one theme in the results that reflected some change in social support (e.g., the availability of parents, changes in friendships, reduced instrumental support, or lack of information regarding the diagnosed child). Of these, ten aimed to understand the experience of cancer [13,26,41,42,53–58]. Results of these studies demonstrate many common challenges for siblings, including changes in social support. Siblings indicated receiving less instrumental support than before the cancer diagnosis (e.g., reduced support in getting to activities and doing schoolwork), as well having to step up and provide more instrumental support for the family (e.g., taking on more responsibilities such as babysitting or chores) [13,26,42,53,55,58]. Siblings experienced low levels of emotional support resulting in emotional strain related to fear, jealousy, and worry about parents and their sibling with cancer [13,26,41,54,56,58]. This was often compounded by receiving little informational support about their sibling’s diagnosis and treatment and becoming particularly troublesome when confronted by questions from peers [26,53,57]. Siblings noted less companionship and time with friends [13,26,53,55]. However, these changes in social support were not permanent, and three studies identified reports of improved support and family relationships upon the completion of cancer treatments [26,42,53].

Twelve studies described the perceived needs of siblings through parent, nurse, and sibling reports [31,41,52,59–67]. All respondents reported a need for siblings to have instrumental support. This included distractions from the cancer experience, a sense of normalcy, and support in maintaining their activities, schoolwork, and friendships [52,60–62,66]. Parents and siblings endorsed a need for emotional support for siblings such as having someone to talk to whether that be a friend or a professional counselor [41,52,60,63,64,66]. Siblings shared feeling worried and excluded when they did not understand what was happening with the child with cancer and a need for more informational support [52,53,59,61,67]. Furthermore, siblings expressed a desire to have honest and open communication with their parents about cancer [41,59]. Siblings also conveyed the need for companionship support through physical affection and time with parents and siblings [64]. Lastly, siblings and nurses suggested that appraisal support and validation through acknowledgment for sibling achievements and contributions around the house helped siblings feel “seen” by parents [53,59,61].

Two studies found perceptions of social support and social support needs change in relation to the timing of diagnosis and treatment. The first found that sibling support needs change over time. Siblings wanted more informational support and communication at diagnosis, followed by instrumental support with homework, and emotional support over time, to help sustain coping throughout treatment and during hospitalizations [65]. The second study found that younger siblings perceived more social support from teachers and friends than peers two years after treatment; however, this was not true for adolescent siblings [31].

The Provision and Availability of Support from Formal Supportive Care Programs

Several studies asked parents, nurses, and siblings what types of supportive interventions were needed. Two qualitative studies reported a need for instrumental, emotional, informational, and appraisal supports [33,59]. Four additional studies investigated perceptions of siblings regarding group interventions which had implemented these suggested social supports [25,30,45,68]. Interventions that included instrumental support through practicing problem-focused coping and skill building resulted in siblings reporting greater confidence, self-reflection, and control of their emotions [25,68]. After participating in educational interventions, that provided informational support, siblings were noted to have less fear, anxiety, and preoccupation with cancer [25,68]. Furthermore, offering informational support in the school setting was shown to improve emotional support for siblings by creating a shared understanding among peers at school [30]. Emotional support was facilitated in groups by creating a safe space where siblings were encouraged to share their feelings [25,45,68]. When interventions included parents, siblings reported improved perceptions of their relationships and communication with their parents. These siblings also garnered appraisal support simply by having an intervention focused on them, making them feel noticed and validated [45].

Psychoeducational interventions

Eleven quantitative studies investigated the provision of support through interventions and the related outcomes of participation [14,23,24,28–30,32,35,44–48,40,49]. Four of these studies were modeled on Barrera’s SibCT intervention [24,32,35,49]. Participants in the SibCT intervention met in groups two hours a week for eight weeks. Instrumental support was facilitated through problem-focused coping and skill building; emotional support was provided by encouraging siblings to discuss perceived changes in their lives related to cancer such as friendships, school, and family dynamics; and informational support was provided regarding cancer and its treatments. The SibCT intervention facilitated companionship support through time with other siblings and family during the implementation of the intervention as well as appraisal support through praise and validation from family and facilitators [35]. These interventions were found to significantly reduce anxiety and depression symptoms among siblings who attended [32,35].

Four additional psychoeducational interventions were also evaluated. These varied in duration from one day to six weeks and provided social support through information about cancer and companionship with family and peers in a group setting. Findings in two of these studies showed reduced fear and preoccupation with cancer and improved mood [48,40]. One randomized intervention study [23] demonstrated significantly increased perceptions of social support. It included a standard of care arm that provided access to a psycho-oncologist and follow-up with study staff. The intervention arm was standard of care plus a two-session education and coping seminar for parents and siblings together. Interestingly, anxiety and quality of life improved post-intervention among both groups [23]. Similarly, Nemitz et al. [29] compared a standard of care arm (basic access to psychosocial support and staff) with another group of siblings who received standard of care plus a five session psychoeducational intervention and found no difference between groups, but significant improvements among both groups.

Oncology camp interventions

Four studies evaluated outcomes related to sibling attendance at pediatric oncology camps. Three of these studies demonstrated improved social competence, self-esteem, and self-concept among siblings after participation [28,44,46]. Sidhu et al. [46] also showed the camp experience reduced fear and the perceived impact of cancer on the lives of siblings. Findings from Packman et al. [45] revealed that siblings who attended camp showed a significant reduction of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and anxiety in addition to improved quality of life. The emotional support (e.g., art expressive activities) and companionship offered at camp was believed to lead to these outcomes. One final camp study found no change in sibling depression scores post-camp but did find positive appraisals of social support among siblings after attending camp [47].

Availability of formal support for siblings

Six studies investigated the types of support offered to siblings and families within the healthcare system [14,27,33,66,69,70]. In the first, authors found that 71% of parents reported little to no formalized support for siblings. These results were independent of socioeconomic status or other demographic factors [69]. Another found that 86% of parents received less informational and psychological support than they needed, making it difficult for them to access sibling support or even address difficult subjects with siblings like prognosis. Moreover, siblings generally perceived provider interactions as negative and were unlikely to ask questions to obtain informational support [70].

Three studies found that nurses often provide informal support to siblings. Examples provided by siblings and parents included providing education to siblings as well as praise and encouragement in addition to allowing sibling visitation [33,14]. Nurses also provide a secondary type of support to siblings by providing parent education on strategies to support siblings such as communicating frequently and working to provide normalcy and acknowledgment [27,33]. While nurses’ support was perceived as helpful, it was not associated with decreased perceptions of alienation [14]. Parents generally felt supported by the staff caring for their child with cancer but noted major deficits within the healthcare system in accessing emotional and tangible supports for themselves and siblings [66], and parents felt that siblings suffered most because of this.

Family and Informal Social Support

Several studies pointed to possible predictors of social support including family cohesion [38], family functioning [36], and family environment [45]. Family cohesion, or a sense of bondedness and support within the family, was significantly related to positive social competence and reduced behavioral problems among siblings [39,71]. Similarly, extended hospitalizations and perceived expense of treatments have been associated with poor family functioning and reduced perceptions of social support among siblings [36]. The family environment, specifically perceived low-levels of attention from parents, has been associated with higher rates of unmet support needs among siblings [51]. Two studies [37,57] found that a lack of awareness from parents regarding sibling needs impacted siblings’ ability to have their needs met. Both found that when siblings perceive that parents are overwhelmed, they are less likely to ask for the support they need and put other family members’ needs before their own. Higher parental awareness was found to be related to closer parent and sibling relationships pre-diagnosis, and parents’ ability to problem solve to provide instrumental support, address sibling needs, and offer emotional support [37].

One study looked at how the family members themselves support each other [72], identifying that families flex their roles providing different types of support than they had previously in order to create a sense of strength and family cohesion. Some families reported difficulties discussing sensitive issues such as death or relapse causing reduced emotional support; however, companionship with family members seemed to alleviate this distress.

Finally, Oberoi et al [73], noted that cultural and socioeconomic factors played a role in the type of supports parents believe are helpful to siblings. Authors in this study reported that Latinx parents and parents without financial hardship felt that peer companionship and validation support were most important, while those who reported financial hardship felt that emotional support was a priority. Furthermore, parents with some financial hardship reported a lack of knowledge and information regarding sibling supportive programs, while parents without financial hardship reported logistical concerns like siblings’ school schedules or distance from the hospital.

Discussion

This review aimed to answer questions about social support among siblings of children with cancer. We found that while all studies were based on empirical evidence, relatively few utilized specific frameworks or theories. The experience of childhood cancer is complex, and the use of common social support frameworks may help us link findings and advance our knowledge in this area of research.

The measures used to assess social support varied across the quantitative literature. Eight unique tools were used to examine social support; however, no validated tool was used more than twice. The most commonly used tool was the SPQ, which is not specific to social support. Currently, there are few tools that capture the vast dimensions of social support, and most look at the person providing support. This makes it difficult to identify what types of support are most important to the well-being of siblings of children with cancer or if certain types of support can counteract the loss of another. The challenge of capturing social support in a meaningful way is not new. Many researchers in this area have tried to define a variety of social support constructs and articulate the importance of mindful measurement tool selection in order to understand the mechanisms of action related to social support [74,75].

The examined studies highlight a diverse range of social support, coming from a variety of sources that could be used to create a safety net for siblings of children with cancer. Common themes noted in our review were positive associations between informational support and reduced anxiety or fear. Time with other siblings of children with cancer provided appraisal support, which appeared to help facilitate normalization of the cancer experience and cognitive reframing. These findings suggest that the type of support siblings receive may be as important as the person who facilitates the support. For example, instrumental support in maintaining activities with minimal disturbance, distraction activities to get their mind off cancer, or the regular emotional check-in may be more important than the actual person providing the support. Unfortunately, this possibility has not been directly examined in the current literature. Furthermore, in these studies, age, gender, and stage of cancer treatment hinted at but did not definitely identify differences in perceived social support and need [11,31,51,52], suggesting that timing and developmental stage likely play an unidentified role in the effect of social support on adjustment.

Notably, all of the formal supportive care intervention studies provided opportunities for support (companionship) from family or peers within the intervention. However, perceptions of support were not typically assessed as an outcome of mechanism of intervention action. As another example, camps with peers likely facilitated appraisal support through validation, although appraisal support was rarely assessed. These examples are missed opportunities for examining the effect of social support on outcomes.

Study Limitations

Design and power limitations hamper a full understanding of the impact of social support on sibling adjustment. Very few studies identified specific types of social support and their influence on sibling outcomes, making it difficult to know where to focus future social support interventions. Furthermore, it is unclear whether support from other sources (e.g., peers, teachers, hospital staff) can be as impactful on sibling wellbeing as support from parents.

Several studies included in this review noted difficulties in conducting randomized trials due to small pools of accessible and eligible participants. These factors likely contributed to other limitations including wide variations in terms of sample age, time since diagnosis, and diagnosis of the child with cancer. Authors also noted challenges in recruitment due to parents being overwhelmed and lacking time or resources to facilitate sibling involvement in interventions. While we didn’t include studies focusing on bereaved siblings, the death of a child with cancer was a frequently cited cause for dropping out of a study.

Clinical Implications

Siblings are removed from the hospital setting and do not qualify for traditional mechanisms of supportive care offered through Medicaid or insurance plans, further adding to the barriers of sibling supportive care. Nevertheless, supportive care is an established standard of care for siblings [6]. Two reviewed studies indicated that access to basic standard psychosocial support may be beneficial for all siblings [29,23]. Siblings in both of these studies received informational support related to cancer and coping, demonstrating significant improvements in quality of life, knowledge, and perceived social support. It is likely that informal support from friends, family, and peers also augments sibling adjustment.

Our review found that positive parent and family functioning are important antecedents to perceptions of social support and well-being among siblings, similar to previous research [9]. A thorough family assessment and screening may help identify at-risk siblings who need additional support through counseling, education, validation, or instrumental support with homework or in attending peer activities [76,77].

Based on our findings, both formal supportive care and informal social support overlap may be working together to enhance sibling outcomes, further supporting a need for family-centered care. The Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model [78] is a viable framework to guide this care and sibling support. This model proposes a level of support commensurate with level of need. Screening the family through an ecological assessment would identify family-level issues that may be contributing to sibling distress. Use of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) [79], validated in families of children with cancer, may be particularly useful in this regard. Currently, a sibling specific module is being developed and tested for the PAT to identify siblings who may have greater risk and require more support [76]. Additionally, the Sibling Cancer Needs Assessment [80], used in several studies cited in this review, is validated to assess the specific types of support needs of siblings.

Healthcare practitioners can also offer social support by being aware of the community and online resources for siblings such as pediatric oncology camps (some now virtual), SuperSibs! powered by Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation [81], CopingSpace [82] offered by Ryan’s Case for Smiles, and now, virtual SibShops [83]. These resources can augment what is being provided within the healthcare system. Siblings appear to benefit from a variety of types of social support and providing multidimensional support may help create a safety net that enhances sibling wellbeing.

Future Directions

Seemingly simple forms of support may be playing a bigger role in the positive adjustment of siblings than we know. A deeper examination of the specific types of social support and their influence on sibling adjustment as well as the importance of the people who provide support would increase our understanding of how to build and provide the most effective supportive care to siblings. Interestingly, very few studies examined the influence of peer support on sibling outcomes.

Future studies should evaluate the long-term impact of social support as well as the analysis of the most impactful types of support for age, gender, and cancer-related variables as this will build a better understanding of the developmental impact of social support on siblings. Specific attention to measurement tools capturing the elements of social support should be sought to investigate how social support may act as mediating or moderating variables in future intervention studies. This will improve our understanding about the types of support that are most useful and to whom. Finally, the use of theoretical models can improve our knowledge regarding social support for siblings of children with cancer by making clear connections and pathways for study.

A large gap in the literature is the inattention to virtual forms of support. No studies examined technology as a means of accessing support. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased utilization of technology to stay connected, technology-based support such as virtual camps or telehealth-based interventions is primed for examination. Studies evaluating social media as a form of social support have been observed in a wide variety of health populations such as individuals with diabetes [84] and those grieving from the death of loved ones [85], demonstrating that integrating technology into the support of siblings may be a viable and low-cost option for supportive interventions.

Conclusions

Social support is a prevalent construct in the sibling research literature. Despite a limited number of multidimensional social support tools and some methodological limitations, there continues to be a clear link between social support and healthy adaptation among siblings of children with cancer. Future work is warranted to identify the most beneficial types of support for siblings based on discrete characteristics of siblings (e.g., development) that may play an important role in their adjustment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Funding details: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31NR018987. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Thank you to Mary McFarland for providing guidance on scoping reviews and a final review of this manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- CASSS

Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale

- SSSC

Social Support Scale for Children

- MSPSS

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- SSSS

Social Support Satisfaction Scale

- NSSSQ

Nurse Sibling Social Support Questionnaire

- SCNI

Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument

- SPQ

Sibling Perception Questionnaire

- PTSS

Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms

Appendix I

MEDLINE search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily <1946 to July 12, 2019>

Search Strategy:

sociological factors/ or social capital/ or social support/ [social support headings] (67894)

((psycho-social or psychosocial or socio-psych* or emotion* or soci*) adj3 (support* or outcome* or integrat* or network*)).ti,ab,kw. [social support keywords] (84503)

1 or 2 [social support] (125874)

siblings/ [siblings headings] (10502)

(sibling* or brother* or sister* or stepbrother* or step-brother* or stepsister* or step-sister* or stepfamil* or stepchild* or twin or twins or triplet*).ti,ab,kw. [siblings keywords] (163740)

4 or 5 [siblings] (93374)

3 and 6 [social support of siblings set] (1481)

(leukemia or leukemi* or leukaemi* or “childhood ALL” or AML or lymphoma or lymphom* or hodgkin or hodgkin* or T-cell or B-cell or non-hodgkin or sarcoma or sarcom* or “sarcoma, Ewing’s” or Ewing* or osteosarcoma or osteosarcom* or “wilms tumor” or wilms* or nephroblastom* or neuroblastoma or neuroblastom* or rhabdomyosarcoma or rhabdomyosarcom* or teratoma or teratom* or hepatoma or hepatom* or hepatoblastoma or hepatoblastom* or PNET or medulloblastoma or medulloblastom* or PNET* or “neuroectodermal tumors, primitive” or retinoblastoma or retinoblastom* or meningioma or meningiom* or glioma or gliom* or “pediatric oncology” or “paediatric oncology” or “childhood cancer” or “childhood tumor” or “childhood tumors” or “brain tumor*” or “brain tumour*” or “brain neoplasms” or “central nervous system neoplasm” or “central nervous system neoplasms” or “central nervous system tumor*” or “central nervous system tumour*” or “brain cancer*” or “brain neoplasm*” or “intracranial neoplasm*” or “leukemia lymphocytic acute”).ti,ab,kw. [Cochrane childhood cancer keywords] (1001703)

exp Neoplasms/ OR “cancer survivors”/ (3198759) [cancer headings]

(Cancer* or Carcinoma* or Sarcoma* or Neoplasm* or neoplasti* or Lymphoma* or leukaemi* or Leukemi* or Adenocarcinoma or Glioma* or Metast* or Adenoma* or Melanoma* or Hepatoma* or ((Malignant or Malignancy) adj4 (tumor* or tumour* or tumo?r*)) or Acanthoma or Acrospiroma or Adamantinoma or Adenofibroma or Adenolymphoma or Adenomyoepithelioma or Adenomyoma or Adenosarcoma or Ameloblastoma or Angiofibroma or Angiokeratoma or Angiolipoma or Angiomyolipoma or Angiomyoma or angiosarcoma or Apudoma or astrocytoma or blastoma or “Bowen disease” or “Bowen’s Disease” or carcinoid or carcinosarcoma or “Carney Complex” or Cementma or Cholangiocarcinoma or Chondroblastoma or Chondroma* or chondrosarcoma or choriocarcinoma or Craniopharyngioma or Cystadenocarcinoma or Cystadenofibroma or Cystadenoma or “Denys-Drash Syndrome” or Dermatofibrosarcoma or “Dupuytren Contracture” or dysgerminoma or “Dysplastic Nevus Syndrome” or “eccrine porocarcinoma” or ependymoblastoma or Ependymoma or Erythroleukemia or esthesioneuroblastoma or Fibroadenoma or Fibroma* or fibromyxosarcoma or Fibrosarcoma or Ganglioglioma or Ganglioneuroblastoma or Ganglioneuroma or “Gardner Syndrome” or Gastrinoma or glioblastoma or gliosarcoma or Glucagonoma or Gonadoblastoma or Hamartoma or Hemangioblastoma or Hemangioendothelioma or Hemangioma or Hemangiopericytoma or Hemangiosarcoma or hepatoblastoma or Hidrocystoma or Histiocytoma or Hodgkin* or immunocytoma or “Immunoglobulin Light-chain Amyloidosis” or “immunoproliferative small intestinal disease” or Insulinoma or “Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome” or “Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome” or Leiomyoma* or leiomyosarcoma or Leukoplakia or leukosarcoma or “Li-Fraumeni Syndrome” or “Limbic Encephalitis” or “linitis plastica” or lipoblastoma or Lipoma or Liposarcoma or Luteoma or lymphangioleiomyomatosis or Lymphangioma or lymphangiomyoma or lymphangiosarcoma or lymphoblastoma or lymphoepithelioma or lymphosarcoma or “Lynch Syndrome” or Mastocytosis or Medulloblastoma or “Meigs Syndrome” or “Meningeal Carcinomatosis” or Meningioma or Mesenchymoma or mesonephroma or mesothelioma or “minimal residual disease” or “mucosal residual disease” or “Muir Torre syndrome” or “Muir-Torre Syndrome” or “Multiple Pulmonary Nodules” or “Mycosis Fungoides” or Myelolipoma or myeloma or Myoepithelioma or Myofibroma or Myofibromatosis or Myoma or Myopericytoma or Myosarcoma or Myxoma or myxosarcoma or nephroblastoma or Nephroma or Neurilemmoma or neuroblastoma or Neurocytoma or neuroepithelioma or Neurofibroma or Neurofibromatoses or Neurofibrosarcoma or Neuroma or Neurothekeoma or Odontoma or Oligodendroglioma or “Opsoclonus-Myoclonus Syndrome” or Osteoblastoma or Osteochondroma or Osteochondromatosis or osteoma or Osteosarcoma or (Paget* adj2 disease*) or “pagetoid Reticulosis” or “Pallister-Hall Syndrome” or “Pancoast Syndrome” or Papilloma or Paraganglioma or “Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome” or Pheochromocytoma or “pilocytic astrocytoma” or Pilomatrixoma or Pinealoma or plasmacytoma or “pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma” or “Polycythemia Vera” or Poroma or Prolactinoma or “Proteus Syndrome” or “Pseudomyxoma Peritonei” or reticulosarcoma or retinoblastoma or RHabdomyo* or seminoma or “Sezary Syndrome” or “Sister Mary Joseph nodule” or “Sister Mary Joseph’s Nodule” or somatostatinoma or “Sturge-Weber Syndrome” or subependymoma or Syringoma or teratocarcinoma or Thecoma or Thymoma or “Tuberous Sclerosis” or “Urticaria Pigmentosa” or Vipoma or “WAGR Syndrome” or “Waldenstroem macroglobulinemia” or “Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome”).ti,ab,kw. [cancer keywords] (3180810)

7 and (8 or 9 or 10) [social support of siblings + all cancer terms] (216)

APPENDIX

Appendix II. Qualitative Quality Assessment Table.

Higher scores reflect less risk of bias in the study design and analysis.

| Author / Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrera [25] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Carlsen [57] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.90 |

| D’Urso [42] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.85 |

| Jenholt-Nolbris [68] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.55 |

| Kaatsız [56] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Løkkenberg [41] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.80 |

| Long [53] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| McGrath [54] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.70 |

| Murray [34] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

| O’Shea [59] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

| Pariseau [37] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Plessis [66] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.65 |

| Prchal [26] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.80 |

| Samson [55] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Sidhu [60] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Sloper [13] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

| Tasker [61] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Toft [64] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.75 |

| Van Schoors [72] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.80 |

| vonEssen [62] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

| Wakefield [63] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

Appendix III. Quantitative Quality Assessment Table.

Higher scores reflect less risk of bias in the study design and analysis.

| Author/ Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderfer [11] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Alderfer [12] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Ballard [67] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.82 |

| Barrera [35] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.85 |

| Barrera [32] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Barrera [10] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Barrera [31] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Barrera [24] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.96 |

| Cohen [38] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Dolgin [48] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Dolgin [71] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.86 |

| D’Urso [43] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.73 |

| Houtzager [40] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 |

| Lövgren [69] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.60 |

| Lövgren [70] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 2 | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.83 |

| Marques [36] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.91 |

| McDonald [51] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Murray [27] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Murray [33] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.82 |

| Murray [28] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.80 |

| Niemitz [29] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Packman [44] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Prchal [23] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.96 |

| Salavati [49] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Sidhu [46] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

| Wellisch [47] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.95 |

Appendix IV. Multi-Method Quality Assessment Table.

Both the qualitative and quantitative quality assessment questions were used for multi-method studies. Higher scores reflect less risk of bias in the study design and analysis.

| Author/ Citation | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freeman [65] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.60 |

| Havermans [50] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.86 |

| Kobayashi [1] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.93 |

| Oberoi [73] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | NA | 2 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.92 |

| Packman [45] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.81 |

| Patterson [52] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.87 |

| Sjoberg [30] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.81 |

| Visočnik [58] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.62 |

| Wang [39] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.90 |

| Yu [14] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.86 |

Footnotes

Conflicting Interests: Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Ethical Statement: As this is a review of current literature and no new data was collected or obtained from human subjects, this project was deemed exempt from IRB review.

Data Availability Statement: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were analyzed during the current study.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Wawrzynski, Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital, Pediatric Critical Care Services; &; University of Utah, College of Nursing 10 S. 2000 E. Salt Lake City, UT. 84111.

Megan R. Schaefer, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Department of Psychology.

Nena Schvaneveldt, University of Utah, Eccles Health Science Library.

Melissa A. Alderfer, Center for Healthcare Delivery Science, Nemours Children’s Health System; &; Department of Pediatrics, Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University.

References

- 1.Kobayashi K, Hayakawa A, Hohashi N (2015) Interrelations between siblings and parents in families living with children with cancer. J Fam Nurs 21 (1):119–148. doi: 10.1177/1074840714564061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodgate R L. (2006) Siblings’ Experiences with Childhood Cancer: A Different Way of Being in the Family. Cancer Nurs 29 (5):406–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute (2018) Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ®). National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-pdq. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderfer MA, Long KA, Lown EA, Marsland AL, Ostrowski NL, Hock JM, Ewing LJ (2010) Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology 19 (8):789–805. doi: 10.1002/pon.1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long KA, Lehmann V, Gerhardt CA, Carpenter AL, Marsland AL, Alderfer MA (2018) Psychosocial functioning and risk factors among siblings of children with cancer: An updated systematic review. Psychooncology 27 (6):1467–1479. doi: 10.1002/pon.4669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhardt CA, Lehmann V, Long KA, Alderfer MA (2015) Supporting Siblings as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 Suppl 5 (S5):S750–804. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/social-support. Accessed July 12 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Li X, Lou C, Sonenstein FL, Kalamar A, Jejeebhoy S, Delany-Moretlwe S, Brahmbhatt H, Olumide AO, Ojengbede O (2014) The association between social support and mental health among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments. J Adolesc Health 55 (6 Suppl):S31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchino BN (2009) Understanding the Links Between Social Support and Physical Health: A Life-Span Perspective With Emphasis on the Separability of Perceived and Received Support. Perspect Psychol Sci 4 (3):236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrera M, Fleming CF, Khan FS (2004) The role of emotional social support in the psychological adjustment of siblings of children with cancer. Child Care Health Dev 30 (2):103–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2003.00396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alderfer MA, Hodges JA (2010) Supporting Siblings of Children with Cancer: A Need for Family-School Partnerships. School mental health 2 (2):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9027-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderfer MA, Stanley C, Conroy R, Long KA, Fairclough DL, Kazak AE, Noll RB (2015) The social functioning of siblings of children with cancer: a multi-informant investigation. J Pediatr Psychol 40 (3):309–319. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloper P (2000) Experiences and support needs of siblings of children with cancer. Health Soc Care Community 8 (5):298–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00254.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J, Bang KS (2015) Perceived Alienation of, and Social Support for, Siblings of Children With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 32 (6):410–416. doi: 10.1177/1043454214563753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8 (1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Joanna Briggs Institute (2017) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil H (2020) Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, JBI [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tuncalp O, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 169 (7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IBM Corp (2017) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 25 edn., Armonk, NY: IBM Corp [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C (2016) PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wawrzynski SE, Schaefer MR, Schvaneveldt N, Alderfer MA (2021) Social Support in Siblings of Children with Cancer: A Scoping Review Protocol. Protocol Registry of Evidence Reviews at the University of Utah, Online. doi: 10.26052/0DC236H3A1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC (2004) Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/48b9b989-c221-4df6-9e35-af782082280e/view/a1cffdde-243e-41c3-be98-885f6d4dcb29/standard_quality_assessment_criteria_for_evaluating_primary_research_papers_from_a_variety_of_fields.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prchal A, Graf A, Bergstraesser E, Landolt MA (2012) A two-session psychological intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 6 (1):3. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrera M, Atenafu E, Nathan PC, Schulte F, Hancock K (2018) Depression and Quality of Life in Siblings of Children With Cancer After Group Intervention Participation: A Randomized Control Trial. J Pediatr Psychol 43 (10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrera M, Neville A, Purdon L, Hancock K (2018) “It’s Just for Us!” Perceived Benefits of Participation in a Group Intervention for Siblings of Children With Cancer. J Pediatr Psychol:995–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prchal A, Landolt MA (2012) How siblings of pediatric cancer patients experience the first time after diagnosis: a qualitative study. Cancer Nurs 35 (2):133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray JS (1995) Social support for siblings of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 12 (2):62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray JS (2001) Self-concept of siblings of children with cancer. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 24 (2):85–94. doi: 10.1080/01460860116709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niemitz M, Goldbeck L (2018) Outcomes of an enhancement study with additional psychoeducational sessions for healthy siblings of a child with cancer during inpatient family-oriented rehabilitation. Psychooncology 27 (3):892–899. doi: 10.1002/pon.4599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjoberg I, Pole JD, Cassidy M, Boilard C, Costantini S, Johnston DL (2018) The Impact of School Visits on Siblings of Children With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 35 (2):110–117. doi: 10.1177/1043454217735897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrera M, Andrews GS, Burnes D, Atenafu E (2008) Age differences in perceived social support by paediatric haematopoietic progenitor cell transplant patients: a longitudinal study. Child Care Health Dev 34 (1):19–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrera M, Chung JYY, Fleming CF (2004) A group intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 22 (2):21–39 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray JS (2001) Social support for school aged siblings of children with cancer: A comparison between parents and sibling perceptions. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 18 (3):90–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray JS (2002) A qualitative exploration of psychosocial support for siblings of children with cancer. J Pediatr Nurs 17 (5):327–337. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.127177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrera M, Chung JYY, Greenberg M, Fleming C (2002) Preliminary investigation of a group intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients. Child Health Care 31 (2):131–142 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marques G, Araujo B, Sa L (2018) The impact of cancer on healthy siblings. Rev Bras Enferm 71 (4):1992–1997. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pariseau EM, Chevalier L, Muriel AC, Long KA (2020) Parental awareness of sibling adjustment: Perspectives of parents and siblings of children with cancer. J Fam Psychol 34 (6):698–708. doi: 10.1037/fam0000615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen DS, Friedrich WN, Jaworski TM, Copeland D, Pendergrass T (1994) Pediatric cancer: predicting sibling adjustment. J Clin Psychol 50 (3):303–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang RH, Martinson IM (1996) Behavioral responses of healthy Chinese siblings to the stress of childhood cancer in the family: a longitudinal study. J Pediatr Nurs 11 (6):383–391. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(96)80083-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houtzager BA, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF (2001) Supportive groups for siblings of pediatric oncology patients: impact on anxiety. Psychooncology 10 (4):315–324. doi: 10.1002/pon.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lokkeberg B, Sollesnes R, Hestvik J, Langeland E (2020) Adolescent siblings of children with cancer: a qualitative study from a salutogenic health promotion perspective. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 15 (1):1842015. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1842015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D’Urso A, Mastroyannopoulou K, Kirby A (2017) Experiences of posttraumatic growth in siblings of children with cancer. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 22 (2):301–317. doi: 10.1177/1359104516660749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Urso A, Mastroyannopoulou K, Kirby A, Meiser-Stedman R (2018) Posttraumatic stress symptoms in young people with cancer and their siblings: results from a UK sample. J Psychosoc Oncol 36 (6):768–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Packman W, Fine J, Chesterman B, vanZutphen K, Golan R, Amylon MD (2004) Camp Okizu: preliminary investigation of a psychological intervention for siblings of pediatric cancer patients. Children’s Health Care 33 (3):201–215 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Packman W, Mazaheri M, Sporri L, Long JK, Chesterman B, Fine J, Amylon MD (2008) Projective drawings as measures of psychosocial functioning in siblings of pediatric cancer patients from the Camp Okizu Study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 25:44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sidhu R, Passmore A, Baker D (2006) The effectiveness of a peer support camp for siblings of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 47 (5):580–588. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wellisch DK, Crater B, Wiley FM, Belin TR, Weinstein K (2006) Psychosocial impacts of a camping experience for children with cancer and their siblings. Psychooncology 15 (1):56–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolgin MJ, Somer E, Zaidel N, Zaizov R (1997) A structured group intervention for siblings of children with cancer. Journal of Child and Adolescent Group Therapy 7 (1):3–18 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salavati B, Seeman MV, Agha M, Atenafu E, Chung J, Nathan PC, Barrera M (2014) Which siblings of children with cancer benefit most from support groups? Child Health Care 43 (3):221–233 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Havermans T, Eiser C (1994) Siblings of a child with cancer. Child Care Health Dev 20 (5):309–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1994.tb00393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDonald FE, Patterson P, White KJ, Butow P, Bell ML (2015) Predictors of unmet needs and psychological distress in adolescent and young adult siblings of people diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology 24 (3):333–340. doi: 10.1002/pon.3653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patterson P, Millar B, Visser A (2011) The development of an instrument to assess the unmet needs of young people who have a sibling with cancer: piloting the Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument (SCNI). J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 28 (1):16–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Long KA, Marsland AL, Wright A, Hinds P (2015) Creating a tenuous balance: siblings’ experience of a brother’s or sister’s childhood cancer diagnosis. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 32 (1):21–31. doi: 10.1177/1043454214555194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGrath P, Paton MA, Huff N (2005) Beginning treatment for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: the family connection. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 28 (2):97–114. doi: 10.1080/01460860590950881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samson K, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA (2016) A qualitative analysis of the impact of childhood cancer on the lives of siblings at school, in extracurricular activities, and with friends. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 4 (4):362–372 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaatsız MAA, Öz F (2020) I’m Here, Too: Being an Adolescent Sibling of a Pediatric Cancer Patient in Turkey. J Pediatr Nurs 51:e77–e84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlsen LT, Christensen SR, Olesen SP (2019) Adaption strategies used by siblings to childhood cancer patients. Psychooncology 28 (7):1438–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Visočnik N, Lazar MB, Žvelc G (2018) Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in siblings of children with cancer. Znanstveni prispevki [Google Scholar]

- 59.O’Shea ER, Shea J, Robert T, Cavanaugh C (2012) The needs of siblings of children with cancer: a nursing perspective. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 29 (4):221–231. doi: 10.1177/1043454212451365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sidhu R, Passmore A, Baker D (2005) An investigation into parent perceptions of the needs of siblings of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 22 (5):276–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tasker SL, Stonebridge GG (2016) Siblings, You Matter: Exploring the Needs of Adolescent Siblings of Children and Youth With Cancer. J Pediatr Nurs 31 (6):712–722. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.von Essen L, Enskar K (2003) Important aspects of care and assistance for siblings of children treated for cancer: a parent and nurse perspective. Cancer Nurs 26 (3):203–210. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200306000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wakefield CE, McLoone J, Butow P, Lenthen K, Cohn RJ (2013) Support after the completion of cancer treatment: perspectives of Australian adolescents and their families. European Journal of Cancer Care 22 (4):530–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toft T, Alfonsson S, Hovén E, Carlsson T (2019) Feeling excluded and not having anyone to talk to: Qualitative study of interpersonal relationships following a cancer diagnosis in a sibling. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 42:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Freeman K, O’Dell C, Meola C (2003) Childhood brain tumors: children’s and siblings’ concerns regarding the diagnosis and phase of illness. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 20 (3):133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plessis J, Stones D, Meiring M (2019) Family experiences of oncological palliative and supportive care in children: can we do better? Int J Palliat Nurs 25 (9):421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ballard KL (2004) Meeting the needs of siblings of children with cancer. Pediatr Nurs 30 (5):394–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jenholt Nolbris M, Ahlstrom BH (2014) Siblings of children with cancer - their experiences of participating in a person-centered support intervention combining education, learning and reflection: pre- and post-intervention interviews. Eur J Oncol Nurs 18 (3):254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lovgren M, Mogensen N, Harila-Saari A, Lahteenmaki PM, Kreicbergs U (2019) Sweden and Finland need to improve the support provided for the siblings of children with cancer. Acta Paediatr 108 (2):369–370. doi: 10.1111/apa.14616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lövgren M, Udo C, Alvariza A, Kreicbergs U (2020) Much is left unspoken: Self-reports from families in pediatric oncology. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 67 (12):e28735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dolgin MJ, Blumensohn R, Mulhern RK, Orbach J, Sahler OJ, Roghmann KJ, Carpenter PJ, Barbarin OA, Sargent JR, Zeltzer LK, Copeland DR (1997) Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: Cross- cultural aspects. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology:1–14 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Schoors M, De Mol J, Verhofstadt LL, Goubert L, Van Parys H (2020) The family practice of support-giving after a pediatric cancer diagnosis: A multi-family member interview analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 44:101712. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oberoi AR, Cardona ND, Davis KA, Pariseau EM, Berk D, Muriel AC, Long KA (2020) Parent decision-making about support for siblings of children with cancer: Sociodemographic influences. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 8 (2):115 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barrera M (1986) Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. Am J Community Psychol 14 (4):413–445. doi: 10.1007/bf00922627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG (2001) Social relationships and health: challenges for measurement and intervention. Adv Mind Body Med 17 (2):129–141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Long KA, Pariseau EM, Muriel AC, Chu A, Kazak AE, Alderfer MA (2018) Development of a Psychosocial Risk Screener for Siblings of Children With Cancer: Incorporating the Perspectives of Parents. J Pediatr Psychol 43 (6):693–701. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barrera M, Hancock K, Atenafu E, Alexander S, Solomon A, Desjardins L, Shama W, Chung J, Mills D (2020) Quality of life in pediatric oncology patients, caregivers and siblings after psychosocial screening: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 28 (8):3659–3668. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05160-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kazak AE (2006) Pediatric Psychosocial Preventative Health Model (PPPHM): Research, practice, and collaboration in pediatric family systems medicine. Fam Syst Health 24 (4):381 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kazak AE, Hwang WT, Chen FF, Askins MA, Carlson O, Argueta-Ortiz F, Barakat LP (2018) Screening for Family Psychosocial Risk in Pediatric Cancer: Validation of the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT) Version 3. J Pediatr Psychol 43 (7):737–748. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Patterson P, McDonald FE, Butow P, White KJ, Costa DS, Millar B, Bell ML, Wakefield CE, Cohn RJ (2014) Psychometric evaluation of the Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument (SCNI): an instrument to assess the psychosocial unmet needs of young people who are siblings of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 22 (3):653–665. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alex’s Lemonade Stand Fund (2020) SuperSibs! https://www.alexslemonade.org/childhood-cancer/for-families/supersibs. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryan’s Case for Smiles (2019) Coping Space. https://copingspace.org/siblings/. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meyer DJ (1994) Sibshops : workshops for siblings of children with special needs. P.H. Brookes Pub. Co., Baltimore [Google Scholar]

- 84.Litchman ML, Walker HR, Ng AH, Wawrzynski SE, Oser SM, Greenwood DA, Gee PM, Lackey M, Oser TK (2019) State of the Science: A Scoping Review and Gap Analysis of Diabetes Online Communities. J Diabetes Sci Technol 13 (3):466–492. doi: 10.1177/1932296819831042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carroll B, Landry K (2010) Logging on and letting out: Using online social networks to grieve and to mourn. Bull Sci Technol Soc 30 (5):341–349 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malecki CK, Demaray MK, Elliott SN, Nolten PW (2000) The child and adolescent social support scale. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harter S (1985) The social support scale for children and adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of personality assessment 52 (1):30–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ribeiro JLP (2011) Inventário de saúde mental. Lisboa: Placebo [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murray JS (2000) Development of two instruments measuring social support for siblings of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 17 (4):229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dubow EF, Ullman DG (1989) Assessing social support in elementary school children: The survey of children’s social support. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 18 (1):52–64 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Patterson P, McDonald F, Butow P, White K, Costa D, Millar B, Bell ML, Wakefield C, Cohn R (2014) Psychometric evaluation of the Sibling Cancer Needs Instrument (SCNI): an instrument to assess the psychosocial unmet needs of young people who are siblings of cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer 22 (3):653–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sahler OJZ, Carpenter PJ (1989) Evaluation of a camp program for siblings of children with cancer. American journal of diseases of children 143 (6):690–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.