Abstract

Objective

The goals of this study are to describe the value and impact of Project HealthDesign (PHD), a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that applied design thinking to personal health records, and to explore the applicability of the PHD model to another challenging translational informatics problem: the integration of AI into the healthcare system.

Materials and Methods

We assessed PHD’s impact and value in 2 ways. First, we analyzed publication impact by calculating a PHD h-index and characterizing the professional domains of citing journals. Next, we surveyed and interviewed PHD grantees, expert consultants, and codirectors to assess the program’s components and the potential future application of design thinking to artificial intelligence (AI) integration into healthcare.

Results

There was a total of 1171 unique citations to PHD-funded work (collective h-index of 25). Studies citing PHD span medical, legal, and computational journals. Participants stated that this project transformed their thinking, altered their career trajectory, and resulted in technology transfer into the commercial sector. Participants felt, in general, that the approach would be valuable in solving contemporary challenges integrating AI in healthcare including complex social questions, integrating knowledge from multiple domains, implementation, and governance.

Conclusion

Design thinking is a systematic approach to problem-solving characterized by cooperation and collaboration. PHD generated significant impacts as measured by citations, reach, and overall effect on participants. PHD’s design thinking methods are potentially useful to other work on cyber–physical systems, such as the use of AI in healthcare, to propose structural or policy-related changes that may affect adoption, value, and improvement of the care delivery system.

Keywords: design, artificial intelligence, personal health records, innovation, infrastructure

INTRODUCTION

Society is undergoing rapid sociotechnical transformations in all industrial sectors, including transportation and energy,1 manufacturing,2 and agriculture.3,4 In each sector, sociotechnical transformations has disrupted routine operations by redefining infrastructure, business models, and policies. In healthcare, advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence promise to better predict disease risk, categorize vague phenotypes, and personalize treatment plans.5,6 These changes will force disruptions in routine operations in medicine.7 To achieve the impact of technology on other industries such as energy or manufacturing, we will need an infrastructure capable of responding to notifications and dynamic risk scoring, business models to support the cost of AI in care, and policy changes to address legal and other challenges.5

Although several strategies could address these challenges, a process called design thinking is especially well-aligned with this class of problems. Design thinking is a systematic innovation approach that emphasizes empathy and engagement of end users in data collection and analysis, and rapid, iterative prototyping to identify design solutions. It also considers both a product aimed at solving the problem and the people who will be using it. Its goal is to gain a full understanding of a problem from all sides, so as to develop comprehensive solutions.8 This model is not new to healthcare—Project HealthDesign (PHD), a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) program, applied design thinking in regard to the creation of personal health records (PHRs).9

The goals of PHD have been described.9 Briefly, it was designed to complement work led by organizations seeking to establish widespread access to PHRs for all people.10 Recognizing the need to align the healthcare system with this new model, PHD sought to expand the vision of personal health records beyond simple electronic copies of patient medical records and encourage the market to use technology to put useful, actionable information into patients’ hands. PHD is an exemplar of a program based in design thinking.

PHD funded 2 cohorts. In the first round, 9 grantee teams—each with different visions for a personal health record—worked separately to gather and analyze data and plan their product designs. There were also periodic meetings of the entire cohort, where teams worked together to refine each team’s vision and identify what might be required for each of the visions to be realized. They sketched out details about how their project would work in the real world using personas;11 discussed the ethical, legal, and social implications of their projects; and visited a maker studio12 to design the look and feel of their products. Round 1-grantees also participated in a special “Day on the Hill” in Washington, DC, where they met with their local House of Representatives leaders and staffers, discussing their project and any policy implications of their work. The goals of the session were primarily to provide exposure to the policy makers, discuss the concept of personal health records, data interoperability, standards, and the specific projects implemented by their constituents, and to gain feedback and insight. Finally, each team created a video demonstration of their project using graphics and nonworking prototypes. Second-round teams built on key findings from Round 1 to develop a common set of utilities for incorporating concepts, identified in Round 1, in personal health records. They focused on observations of daily living, defined as “the unique, idiosyncratic cues, such as sleep adequacy or confidence in self-care, that inform patients about their abilities to manage health challenges and take healthy action.”9,13

Two codirectors of the PHD program worked with an expert focus group to refine the program model. They also worked with consultants who assisted with digital media and knowledge dissemination through websites, a blog, a document repository, and slide presentations. Finally, experts in innovation and ethical, legal, and social issues were funded to assist grantees. These 2 groups of experts worked with grantees throughout the PHD process. A National Advisory Committee of experts in informatics, health policy, and commercialization also helped to select grantees and evaluate progress.

OBJECTIVE

The goals of this study are to describe the value and impact of PHD and explore the applicability of the PHD model to another challenging translational informatics problem: the integration of AI into the healthcare system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This project was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. It comprised 2 studies. The first study examined the reach of PHD-related publications. We asked grantees to provide a list of their PHD publications, and we performed a literature search to identify additional works citing PHD grants. We then calculated total publications and the h-index of each. The h-index is the maximum value of h such that the given author/journal has published h papers that have each been cited at least h times.14 Traditionally used to determine the impact of a specific author, the h-index can be calculated for any set of documents.13 To calculate the h-index of the set of PHD publications, we determined the h-index for each PHD publication, sorted the h-index values in descending order, and determined the maximum value of h publications that have been cited at least h times. We then searched for and collected all references (ie, peer-reviewed literature, conference and abstract proceedings, book chapters, theses, and dissertations) citing this work, and mapped these references to Google Scholar subject domains, a classification scheme with more than 250 terms across 8 broad subject areas.14,15[OBJ] Finally, we conducted a subject domain analysis of the citing literature to establish reach using Google Scholar and Web of Science.

In the second study, PHD stakeholders provided perspectives on the program, its impact, and its potential utility to AI in healthcare. Stakeholders included:

PHD codirectors—senior leadership of the PHD program, including a RWJF manager and a funded, academic senior investigator.

Grantees—principal investigators and coinvestigators who received funding in either Round 1, Round 2, or both rounds, including both academic and industry personnel.

Consultants—experts in 2 areas, innovation and ethical/legal studies.

Other key definitions that guided our work include:

Design thinking—a systematic innovation approach that emphasizes empathy and engagement of end users in data collection and analysis, and rapid, iterative prototyping to identify design solutions.

PHD model—the structure and activities of the PHD program, including cohort building, user engagement, access to experts, prototyping, and exploration of real-world implementation.

We were guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).16 The CFIR is a framework that coordinates numerous measurement constructs that have been associated with effective implementation of innovation programs. In planning our survey, focus group, and interview data collection instruments, we created modified versions of standard questions from relevant CFIR constructs to ensure a comprehensive perspective on the process and context of the PHD experience (Table 1)

Table 1.

Data collection methods mapped to the CFIR constructs

| CFIR Element | Data Source | Topics of Inquiry |

|---|---|---|

| The Intervention (the innovation being implemented) | Surveys, focus groups (grantees) and interviews (PHD codirectors and consultants) |

|

| Document and artifact review | ||

| The Outer Setting (social and political elements outside the organization) | Surveys, focus groups (grantees) and interviews (PHD codirectors and consultants) Document and artifact review |

|

| Citation study | ||

| The Inner Setting (organizational structure and culture) | Surveys, focus groups (grantees) and interviews (PHD codirectors and consultants) |

|

| Document and artifact review | ||

| The Process (procedures and outcomes associated with implementation) | Surveys, focus groups (grantees) and interviews (PHD codirectors and consultants) |

|

| Interviews with key stakeholders | ||

| Citation study |

A survey assessed grantees’ opinions about design thinking and the rationale for using the PHD process to rethink healthcare in a data-enabled environment. We used REDCap, a secure data-capturing system,17 to create and distribute the survey. Participants rated the value of specific PHD components in rounds for which they were funded.

We studied perspectives from PHD codirectors and consultants through 60-minute interviews via videoconference. The interviews explored development of the PHD model, the structure of the program, implementation, grantee selection criteria, differences in the first and second rounds of work, collaborative components, and stakeholder assessment of each component’s value. We also asked participants to consider how the model might be adapted to the challenge of implementing AI in healthcare.

To assess the impact, effectiveness, and transferability of the PHD model, we held a series of 90-minute virtual focus groups with grantees.18 Our goal was to understand their perspectives about PHD’s value to their research, its value to consumer health informatics, and its potential to address the challenges of AI and data science in healthcare settings.

To prepare for the interviews, we conducted background research, reviewing documents related to the design sessions. We also reviewed archived blog posts produced by the PHD program as part of its dissemination strategy.

Data analysis

Reach study

To calculate the h-index of publications related to PHD, we identified all citing references using Google Scholar and Web of Science. Duplicate citations were removed from analysis, and the number of unique citing references were counted. We mapped English-language journal articles (n = 726) and book chapter citations (n = 90) to Google Scholar subject domains, which provided the most information for classification. Each citation was mapped to the most specific 1–3 subcategories available.

We created a treemap in Microsoft Excel, included in this study as a Supplementary File. This map is a visual representation, weighted by frequency, of the number of citations to PHD publications by Google Scholar for all subcategories with at least 5 citations. We updated the h-index in October 2020. Other publication analyses were completed in November 2019.

Impact study

The survey of PHD grantees was analyzed using simple descriptive statistics. Interviews and focus group sessions were transcribed and then analyzed using a qualitative data analysis tool, Dedoose.19 Our background research informed the coding process, which involved creating text excerpts and labeling them with codes.20 We used an open coding approach, identifying all themes without constraint of a theoretical framework; however, because the CFIR was used to design the data collection instruments, themes related to CFIR constructs did emerge. The document analysis involved a review of a variety of planning documents and websites related to PHD. These documents were not coded but influenced coding by enabling the 2 researchers who interpreted the data (JH, LN) to have familiarity with the PHD process, terminology, and actors. Coding was performed by a single researcher (JH) with frequent review and input by a second researcher (LN). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Author KJ, having been a PHD grantee and participant in the study, did not participate in the analysis and interpretation of the data.

RESULTS

Reach study

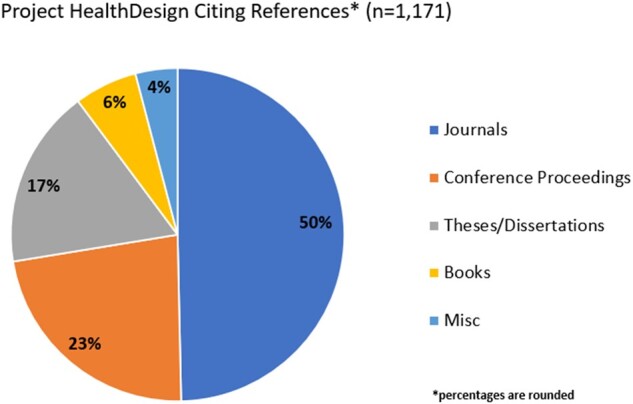

As of the time of this study, 45 publications acknowledged PHD as a source of funding, with a collective h-index of 25. Publications appeared in 36 journals (17 unique titles) and 9 unique conference proceedings. These publications were cited by 1171 unique papers, including 731 citations from 321 journals and 90 citations from chapters in 74 books (Figure 1). The self-citation rate was 2.39% (citations in 1 PHD publication to another in the same set).

Figure 1.

Project HealthDesign citing references.

The top subcategories citing PHD work (Supplementary Figure 1) were medical informatics (218 citations); computer networks and wireless communication (60 citations); nursing (47 citations); databases and information systems (42 citations); and biomedical technology (28 citations).

Impact study

Participants

The survey was conducted only with grantees. We conducted one-on-one interviews with PHD codirectors and consultants. We conducted focus groups with grantees.

Survey findings

There were 14 PHD projects, 9 in the first round and 5 in the second round. However, there were only 13 principal investigators (ie, “grantees”) because 1 was funded for both rounds. We received surveys from 12 out of the 13 principal investigators, including participants from the first round (8/9) and second round (5/5).

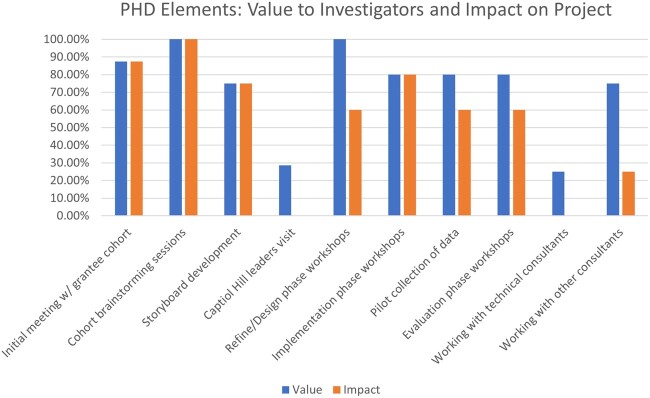

When asked about the value and impact of their PHD experience, grantees overwhelmingly rated interactions with other grantees and facilitated design sessions as the most valuable and impactful (Figure 2). Of note, participants reported 2 components as having value despite having no impact on their initial concept: the Capitol Hill visit and working with technical consultants.

Figure 2.

Grantee perception of PHD component value. Percent of respondents who participated in each element rating it “Valuable” to them, and having a “Positive” impact on their initial design concept.

Eight of 12 (67%) respondents reported ongoing networking with fellow grantees; and that most information exchange was via scholarly journals and conferences. Most respondents (92%) agreed or strongly agreed that PHD affected their career trajectories (change in institution, appointment, or promotion). Nine respondents (75%) strongly agreed or agreed that results of their projects had a sustained impact in biomedicine. Additionally, grantees (83%) said their participation in PHD was likely considered in their performance evaluations at their institutions. When asked about institutional endorsement and support for their projects, respondents reported receiving more support from colleagues (92%) than institutional leaders (58%). When asked about industry impact, 83% said their PHD team had conducted product design or design work in industry settings, and 58% said their work had influenced the design of products.

Interview and focus group findings

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in December 2019 and January 2020. We interviewed the 2 PHD codirectors and 2 of the consultants (1 innovation expert and 1 ethicist). We conducted 3 grantee focus groups, with 3, 4, and 4 participants, respectively. The qualitative data analysis resulted in an analytic dataset with 280 coded excerpts and 58 codes. We found that using the CFIR framework to design the data collection instruments resulted in a robust dataset. We were unable to identify a specific theory or framework that explained the results of the open coding; therefore, we are reporting major themes by participant role: PHD codirectors, consultants, and grantees.

Codirector perspectives

Needs and resources of those served by the organization

PHD codirectors focused on the term better as the driving objective for using a design thinking approach. They emphasized the belief that people needed better personal tools to manage and monitor their health and healthcare and that a more robust infrastructure was needed to facilitate the secure exchange of health data between patients and providers.

Engagement

Overall, PHD codirectors described a process that leveraged expertise of grantees, advisory groups, and subject-matter experts to execute PHD’s 2-fold vision: 1) convening diverse perspectives to reimagine personal health records (PHRs) and 2) developing tools that facilitate the secure flow of health information. They described a communications plan that included print, digital, and social media platforms to communicate the value of PHD developments to health IT, informatics, and lay audiences. The codirectors acknowledged that their focus on advancing the PHD vision may have diverted their attention from being transparent about the PHD model as a collaborative design approach, contributing to grantees’ initial resistance to the PHD model, as 1 codirector explained:

“… the struggle that [grantees] had might’ve been mitigated if we had said, ‘Give us an idea, but don’t expect to do your idea. We just want to see how you think. ’”

External policy and incentives

PHD codirectors noted the timing of PHD, at the height of healthcare reform and policy debates about large-scale implementation of digital healthcare. Given the significance of these issues to PHD, leaders believed that the greatest potential for impact was to connect the PHD vision to policy. For example, several advisory board members were members of groups drafting policy on the meaningful use of health IT. They testified before policy makers about the value of PHD findings. PHD advisors also contributed to public discourse related to the expansion of privacy laws aimed at improving patient access to their EHR data.

Transferability of PHD model to AI in healthcare

Leaders’ discussion of transferability to AI were represented by 2 primary themes, problem structuring and expertise of the future.

Problem Structuring

The PHD model was useful for finding different ways to characterize and structure problems. This was felt to be a particularly useful feature for implementing AI in medicine. As one participant noted:

“… when I think about adopting AI for clinical care, I think that the questions you need to be thinking about include what is the problem and where does the problem get structured? So, with guidelines, the problem gets structured far away from the exact patient encounter. But with a code or an emergency situation… the problem gets structured in the moment that you're trying to analyze it. And so, the ability to structure, to know how the problem was structured so you can interpret the answer. It's going to be key for people using AI techniques in healthcare. ”

Expertise of the future

Another theme was the expertise that would be required in the future; examples included disciplines such as computer science and biology. The inter-disciplinary design of the PHD program aimed to create cohorts of transdisciplinary thinkers, and leaders felt this would be essential for AI integration in healthcare.

Consultant perspective

Building trust

Consultants noted that their main role in PHD was during the innovation sessions, with limited grantee engagement in between these sessions. Consultants expressed some concern about the clarity of their role in the process. The ethics consultant noted some grantees perceived recommendations to engage an ethics consultant as punitive and “finger-wagging.” Helping grantees to appreciate the expertise of the consultants encouraged engagement by the grantees.

The innovation consultant facilitated design workshops and collaborated with leaders to create the structure and itinerary for each PHD session. The challenge for him was to balance the goals of PHD with how grantees were accustomed to working. He described the discomfort participants can experience when engaging in immersive innovation activities such as role-playing, building physical prototypes, and working with toys, such as robots:

“There was a natural tension, what we would call a creative tension between the way they normally work and the way they were being asked to work here. I mean the process itself allows people to… if you’re willing to let go for a few minutes it’s going to come around, and the theory is you’ll be better qualified and more capable of answering the aims that you have by having understood the other grantees in the room, as well as… the overarching ‘what can we do together’ vs ‘what do we need to do individually’ for the group.”

Transferability of PHD model to AI in healthcare

Vision videos were used to synthesize the knowledge generated from design workshops and to communicate user stories. The innovation expert felt the videos were effective in helping consumers understand the benefit of using personal health technologies to monitor and manage their health and expressed the potential utility of similar educational tools for communicating the value of AI in healthcare.

Grantee perspective

Learning climate

Grantees described the learning climate as engaging and enriching, noting interdisciplinarity and the creation of a safe collaborative environment as valuable aspects of the PHD model. They also credited the diversity of perspectives with challenging their thinking and assumptions about innovative approaches to solving clinical problems, as 1 grantee recalled:

“I learned a lot from my peers at those sessions and about creative ways to approach user-centered design problems, not just thinking about user-centered design as something you just take off the shelf but to actively think about what methods are the right methods and what are the scientific questions around developing those methods? That was… new to me, the whole discipline of design and how it can apply in healthcare.”

Access to knowledge and information

Statements related to grantees’ access to knowledge about and training on the mechanics of the PHD model highlight aspects of engagement that shaped grantees initial response toward the experience. The intent of the PHD model was to build on the grantees’ preliminary proposals by employing an iterative and collaborative process to deconstruct and then work collaboratively to develop a common set of standards that could be applied across multiple projects. The focus on collective innovation was embedded in the design of the PHD model but was initially not explicitly touted as a design thinking, user-centric approach. This led to grantees’ initial resistance to the model and other unnerving experiences, including being asked to diverge from their research plan and adapt to different dispositions toward team members during role play, presentations, and other performative exercises.

“I think I found it initially to be a frustrating experience because it took us a while, I think, to develop a common vocabulary. But once we did, I think we generated a lot of innovation. I like how the [facilitators] forced us to places that I found to be kind of uncomfortable, experimenting with different ways of sharing information and brainstorming and critiquing. I think it was a useful exercise. I unfortunately haven’t had the chance to do it again.”

Another grantee summarized: “That was some pain for some gain.”

Grantees reported more favorable experiences after training on design-thinking and user-centered design principles, describing them as enriching, engaging, and sustainable more than a decade after participating in PHD.

External policy

Grantees found the policy visit to Capitol Hill in Washington, DC to have minimal value. While some acknowledged the intrinsic value of gaining skills to communicate their research more effectively to policy makers, they agreed that they were challenged by the lack of clear goals for the visit. One grantee shared that it would have been valuable to focus on policy early in the process, and clarify and provide guidance on what she referred to as the “small p policy” (ie, focused specifically on PHR elements) versus the “large P policy,” (ie, the multiple layers of policy in government, health systems, health plans, and foundations).

Research practices and career impact

Grantees who represented academic medicine, computer science, and the design field noted that PHD’s impact on their career trajectory was transformative. As 1 investigator noted in this exemplary statement:

“This project convinced me I could be a researcher because I had no idea you could do this kind of research in an academic environment. I don't think I would have gone on for my PhD if I hadn’t been involved in this because I was taking the typical industry approach of, ‘Hey, I have this cool idea for now. I’ll just build it and then it’ll be great.’ So, it exposed me to people who had already been working in this area that knew a lot more than I did about this. The level of rigor it instilled in me to go and understand everything that’s come before—I know others have already said this—was really I think what drove my scientific interest.”

Grantees also reflected on PHD’s impact on their practice as mentors, exemplified by this comment:

“I use this now in all of my teaching, which has gone totally into a different model. But also engaging the students to look at this as an example of why you need to think differently, focus on user-centered design… and focus on complexity and interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary work. It’s a lot to ask, but I find the students are extremely interested in having this kind, the PHD example.”

Impact in industry

The work of 1 PHD team concerned with privacy and transparency in personal health records was representative of how grantees used their PHD experiences to impact industry. Another grantee noted that the industry impact arose from a job change:

“I went into industry because we saw such the impact of influence and the excitement around what design can do in the world of healthcare and how it can make a difference for patients. It created in our imagination, not just mine, but my students, that maybe we could do more.”

Resources

Funding was the most commonly noted constraint in grantees’ achieving their goals. Several noted that they would have liked to test the interventions they developed in larger subsequent grants. They recommended a multi-phased funding model that would fund experimentation, refine the innovation in phase 1, and implementation and evaluation in phase 2.

Transferability of the PHD model to AI in healthcare

Grantees generally felt that, for the PHD model to contribute value, the initiative would need a concept more focused than “AI in healthcare.” They felt that complex social questions that underlie cyberphysical or sociotechnical solutions may lend themselves to a PHD-like approach, including bias in AI data and algorithms, and dealing with inaccurate predictive models. One grantee noted that the communications among PHD participants was “refreshing” in that people were unafraid to take on challenging issues. Grantees also focused on the interdisciplinary nature of the PHD model and how that might be useful for AI in healthcare.

“I think you’d have to maybe just think a little differently about who are the stakeholders? What are the questions? They’re not exactly like Project Health Design, but it may be even more imperative to have multiple stakeholders come together, particularly those outside of the technology and healthcare.”

DISCUSSION

Design thinking in biomedical informatics is a relatively new and underutilized method for addressing technology, people, and organizational issues around an innovation. As such, it is important to understand its effectiveness and assess generalizability to new areas.

The ambitious approach and inclusion of design thinking in PHD initially created cognitive dissonance among the grantees. These highly competitive investigators entered into the program believing their job was to implement a solution to a problem they had identified and convincingly argued was solvable using their approach. In the first cohort meeting they learned the goal of the program was to challenge their beliefs, values, and attitudes about the project to improve both their work as well as projects of their cohort members. After an initial uncomfortable period, grantees found the experience valuable and stimulating.

PHD included activities to expand the thinking of the cohort, some of which were deemed highly successful—such as the storyboard development and group brainstorming—and others of which were less well received. However, those activities that had little impact on grantees’ design concepts were still viewed as having some value, in retrospect. Experiences that connected grantees to end users, a core feature of design thinking21 were rated most highly. The grantees found the engaging, interdisciplinary, and collaborative approach, including in-person meetings, to be an important aspect of the program. This finding is consistent with others who have asserted the importance of this type of climate for design-thinking projects.21,22

Publications arising from PHD were highly cited, suggesting the program influenced the increase in design research in health informatics. Moreover, works citing the PHD publications were in a wide selection of journals, such as informatics, computer science, medical specialties, technology law, and architecture—an encouraging endorsement of PHD’s inter-disciplinary focus.

Importantly, it appears that the multi-institutional nature of the cohort influenced not only the products being designed, but also the participants. Our study found nearly unanimous agreement that this strategy positively affected subsequent research conducted by investigators and impacted their career trajectory. Leaders noted that PHD grantees learned new ways to structure and think through problems. Grantees noted that PHD affected their approaches to mentoring and research. The majority of survey respondents reported continued interactions with their cohort to date.

This project was designed, in part, to assess the transferability of the PHD model to the challenge of integrating AI in healthcare.6 Key transferable features are summarized in Table 2. Grantees were generally in agreement that the model used here can help improve both products and implementation strategies. They supported the use of design-thinking as a part of implementing AI interventions at scale in healthcare, recognizing the need for a well thought out focus and adaptation focus.

Table 2.

Features of the PHD model identified as transferable to AI in healthcare

| Transferable Features of PHD | Project HealthDesign | Design Thinking for Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity for addressing complex social questions | Embracing the complexity of patients’ everyday lives. | Implementation complexity for AI, eg, workflow, ethics, management, training, infrastructure. |

| Capacity for developing infrastructure | Infrastructure for PHRs included tech industry (apps), ethical framing, interfacing with EHRs. | Infrastructure involves multiple data sources, cloud computing implications, and management/policy implications. |

| Interdisciplinarity | Teams of people from multiple disciplines working together in ways that push their boundaries. | Transdisciplinary teams and individuals. |

| Focus | PHRs have technical boundaries and the users are known. | AI in healthcare is a broad topic; for a PHD model to work it would need to be focused. |

| Problem structuring | Considering problems from different perspectives. | Structuring problems of prediction/augmentation of human performance through a variety of perspectives eg, various actors, time horizons, situations, levels of aggregation, institutions, etc. |

| Governance and policy | Participants gained experience with the policy process. | Adaptation of traditional governance infrastructure, identification of policy needs. |

The study has limitations. We could not clearly identify commercial descendants from PHD innovations, which would reveal more about the impact of the program. This was a result of the PHD program’s design; all code was made available in open-source libraries and likely influenced a number of products. Second, we were unable to ascertain any direct impact of the Capitol Hill visit on healthcare reform and policy related to electronic health records. PHD participants’ discussions may have helped legislators with their decisions to vote or even write policy. Despite these limitations, this evaluation of the small cohort of investigators provides a window into the potential impact of using the PHD model on other projects and concepts in biomedicine.

CONCLUSION

Project HealthDesign generated significant impact as measured by citations, reach, and overall evolutionary changes in participants. Design thinking methods, like those employed here, are generalizable to other studies focusing on cyberphysical systems, such as AI in healthcare, to propose structural or policy-related changes that may impact adoption, value, and improvement of the care delivery system.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant number 76563).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KJ and LN conceived of the overall study. JH and LN designed, implemented, and analyzed data from the Impact Study, in which KJ was a participant. TK conducted the citation study. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript. All authors approved of the submitted version.

DATAAVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data from the citation analysis can be made available upon request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to all the participants in this project for their time and insight. We thank the Center for Knowledge Management at Vanderbilt University Medical Center for its assistance in analyzing citations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nilsson M, Nykvist B.. Governing the electric vehicle transition–near term interventions to support a green energy economy. Appl Energy 2016; 179: 1360–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tao F, Cheng Y, Zhang L, Nee AY.. Advanced manufacturing systems: socialization characteristics and trends. J Intell Manuf 2017; 28 (5): 1079–94. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patrício DI, Rieder R.. Computer vision and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture for grain crops: a systematic review. Comput Electron Agric 2018; 153: 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talaviya T, Shah D, Patel N, Yagnik H, Shah M.. Implementation of artificial intelligence in agriculture for optimisation of irrigation and application of pesticides and herbicides. Artif Intell Agric 2020; 4: 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matheny ME, Whicher D, Israni ST.. Artificial intelligence in health care: a report from the National Academy of Medicine. JAMA 2020, 323 (6): 509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsell CJ, Stead WW, Johnson KB.. Action-informed artificial intelligence—matching the algorithm to the problem. JAMA 2020;323 (21): 2141–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blue Ridge Health Group. Separating Fact from Fiction: Recommendations for Academic Health Centers on Artificial and Augmented Intelligence [Internet]. Emory University School of Medicine; Report No. 23. http://whsc.emory.edu/blueridge/publications/archive/BlueRidge2018-2019.pdf Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 8.Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C.. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthcare 2016; 4 (1): 11–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan PF, Downs S, Casper G.. Project HealthDesign: rethinking the power and potential of personal health records. J Biomed Inform 2010; 43 (5): S3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westin ALAN. Americans Overwhelmingly Believe Electronic Personal Health Records Could Improve Their Health. John and Mary R. Markle Foundation. 2008. https://markle.policyarchive.org/index?section=5&id=15533 Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 11.Miaskiewicz T, Kozar KA.. Personas and user-centered design: how can personas benefit product design processes? Des Stud 2011; 32 (5): 417–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatch M.The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. New York: McGraw Hill Professional; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen DJ, Keller SR, Hayes GR, Dorr DA, Ash JS, Sittig DF.. Developing a model for understanding patient collection of observations of daily living: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the Project HealthDesign Program. Pers Ubiquitous Comput 2015; 19 (1): 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch JE.An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2005; 102 (46): 16569–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Google Scholar. Google Scholar Metrics. https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/metrics.html Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 16.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC.. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009; 4 (1): 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42 (2): 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodyatt CR, Finneran CA, Stephenson R.. In-person versus online focus group discussions: a comparative analysis of data quality. Qual Health Res 2016; 26 (6): 741–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedoose; 2012. http://www.dedoose.comAccessed December 31, 2012

- 20.Bernard HR, Wutich A, Ryan GW.. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Owen C.Design thinking: notes on its nature and use. Des Res Q 2007;2(1):16–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pande M, Bharathi SV.. Theoretical foundations of design thinking–a constructivism learning approach to design thinking. Think Ski Creat 2020;36:100637. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.