Abstract

Supposed risk of malignant transformation of salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma (SGPA) is an important reason for aggressive retreatment in recurrent pleomorphic adenoma (RPA). However, although the diagnostic category ‘carcinoma ex‐pleomorphic adenoma’ suggests that malignant transformation of a pleomorphic adenoma is a regular event, this has to date not been shown to occur in sequential lesions of one patient. Here, we show the molecular events in transformation to malignancy of a pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Detailed molecular analysis revealed an LIFR/PLAG1 translocation characteristic for pleomorphic adenoma and, next to this, a PIK3R1 frameshift mutation and several allelic imbalances. In subsequent malignant recurrences, the same LIFR/PLAG1 translocation, PIK3R1 frameshift mutation, and allelic imbalances were present in addition to TP53 mutations. Thus, this case not only shows malignant transformation of SGPA, but also demonstrates that molecular analysis can be of help in recognising malignancy in the rare instance of RPA.

Keywords: carcinoma ex‐pleomorphic adenoma; pleomorphic adenoma; malignant transformation; salivary gland; TP53; PIK3R1, NGS, SNP

Introduction

The risk of malignant transformation from the most common salivary gland tumour, salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma (SGPA), to the fifth most frequent salivary gland carcinoma (carcinoma ex‐pleomorphic adenoma; CEPA) is notorious [1, 2]. It can lead to dilemmas in both pathological diagnosis and surgical/adjuvant radiation treatment of primary and recurrent pleomorphic adenoma (RPA). This risk of malignant transformation is, however, rare as only 3% of SGPAs recur at 12.5‐year follow‐up, of which 6% seem to show malignant transformation [1].

The hypothesis that malignant transformation of SGPA occurs is mainly based on the recognition of a pleomorphic adenoma component in malignant salivary gland tumours that are therefore classified as ‘CEPA’. In these tumours, morphological as well as molecular transitions are seen from the benign pleomorphic adenoma component to the malignant carcinoma component [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. At the molecular level, the pleomorphic adenoma component is recognised by the presence of PLAG1 and HMGA2 gene fusions [6, 7, 14], while the malignant component harbours additional mutations such as TP53, c‐MYC, RAS, and P21 [8, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. These events have been shown within CEPA as well as in studies comparing SGPA and CEPA cases but not in sequential lesions from one patient [8, 15, 16, 17, 18].

CEPA can be diagnosed as a primary malignant tumour or as a recurrence after a benign earlier‐resected SGPA [9, 20, 21]. In both cases, malignant transformation is thought to result from progression of an SGPA due to accumulation of genetic changes. SGPA itself is characterised by PLAG1 gene overexpression frequently due to a chromosomal translocation resulting in a gene fusion with several candidate genes [10, 11, 12]. Progression to CEPA due to HMGIC and possibly MDM2 amplification has been suggested [3, 13].

This report shows for the first time that malignant transformation is accompanied by the accumulation of mutations in tumour driver genes in sequentially occurring parotid tumours, by means of targeted next‐generation sequencing (NGS) including copy number variation detection analysis using single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on 12 chromosomes and RNA‐based gene fusion analysis.

Materials and methods

Case

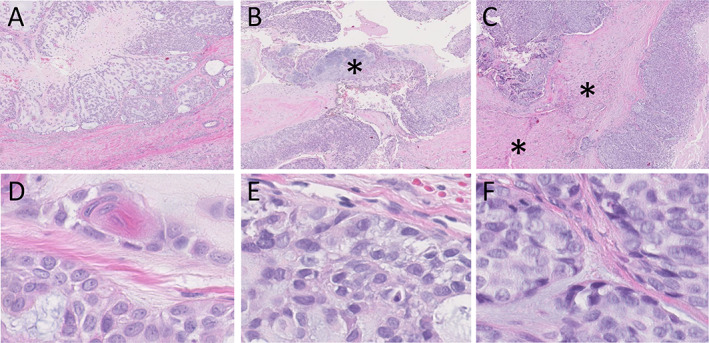

A 35‐year‐old female presented with a painful parotid tumour in the deep lobe without facial nerve palsy. Fine‐needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) revealed a salivary gland tumour, possibly SGPA, uncertainly benign (Milan classification 4b). After a superficial parotidectomy, the tumour was removed with (where possible) the surrounding gland. Histology showed an SGPA (Figure 1A,D), 4 cm in diameter, with a large epithelial component, completely removed without margins. Infiltrative growth, mitotic figures, or necrosis were not observed.

Figure 1.

H&E histology (×2 and ×60 magnification) of the primary, first, and second recurrent tumours (A and D, B and E, C and F, respectively) showing progression of the pleomorphic adenoma without cytonuclear atypia to a carcinoma with more nuclear atypia and mitoses (mitosis in the left upper quadrant of F). Pre‐existent pleomorphic adenoma is seen at the asterisk in (B). Infiltrative growth in skeletal muscle (asterisks) is present in (C).

Three years later, the patient presented with a painful recurrent tumour and paraesthesia of the tongue. FNAC was unsuccessful due to extreme pain. A magnetic resonance imaging showed a local recurrence, which was 5.7 cm in diameter. The tumour and remnant of the deep lobe were resected after a lateral mandibulotomy. The facial nerve was sacrificed and reconstructed. At pathology, a cellular salivary gland tumour was seen, without obvious mitosis or necrosis and with areas clearly classifying as pleomorphic adenoma (Figure 1B,E). Infiltrative growth could not be evaluated as the lesion was excised without margins. The lesion was classified as a benign recurrence reaching into the resection surface. Postoperative radiotherapy (RT, 66 Gray) was administered.

A year later, a lump medial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle was biopsied because the patient refused FNA, and this lesion was classified as suspect for adenocarcinoma. A modified radical neck dissection was performed (levels 1–5) with reconstruction of the accessory nerve and the wound defect. Pathology showed a multinodular basal cell adenocarcinoma (Figure 1C,F), reaching into the resection surface. All 24 lymph nodes were free of tumour. Postoperative RT to the neck (60 Gray) was administered.

To understand the clinical behaviour, all previous slides were reviewed and molecular analysis was performed. DNA and RNA from all the three lesions and normal tissue were isolated. Targeted NGS was performed on an Ion Torrent S5XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) prime systemusing a custom‐made panel for mutation and copy number variation detection using SNPs on 12 chromosomes (for panel information, see supplementary material, Table S1) [22, 23]. In addition, RNA‐based gene fusion detection using the Archer FusionPlex Sarcoma panel (ArcherDx, Boulder, CO, USA) was performed. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Ki‐67 and p53 was performed. The medical ethical committee of the Erasmus Medial Center Rotterdam, The Netherlands, approved this study (MEC‐2020‐0270) on 4 May 2020.

Results

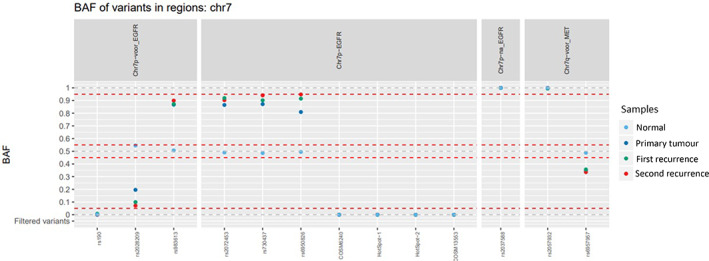

All three lesions showed the same LIFR/PLAG1 gene fusion (see supplementary material, Figure S1), an identical somatic frameshift mutation in the PIK3R1 gene (see supplementary material, Figure S2), and identical patterns of allelic imbalance on chromosomes 5, 7, and 8 (Figure 2 and supplementary material, Figure S3), confirming their clonal relation.

Figure 2.

An identical pattern of allelic imbalance was found on chromosomes 5, 7 (shown in this figure), and 8. The imbalances are present in the primary pleomorphic adenoma, the first recurrence, and the second recurrence. BAF, B‐allele frequency.

In addition, the first recurrent tumour showed a TP53 p.R248Q (c.743G>A) mutation with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 46% (see supplementary material, Figure S2). The second recurrent tumour showed a different TP53 mutation: TP53 p.Y220C (c.659A>G) with a VAF of 51% (see supplementary material, Figure S2).

The low‐level/subclonal presence of both TP53 mutations found in the two recurrences was investigated in the three tumour samples with a very sensitive NGS approach using unique molecular identifiers (ThermoFisher Oncomine™ Lung cfDNA Assay V1; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). With a limit of detection down to 0.3%, no indication was obtained for subclonal presence of these TP53 mutations in the three tumour samples.

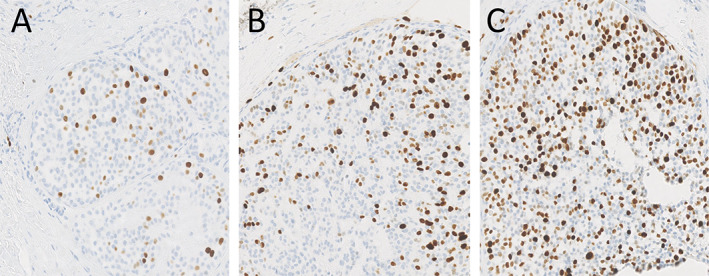

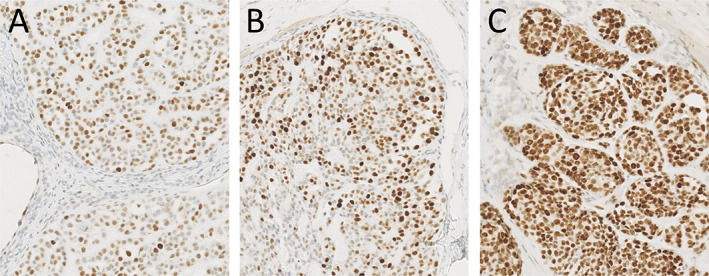

Additional IHC on the three tumours showed a Ki‐67 index of 2, 15, and 40%, respectively (Figure 3). p53 IHC was scored as described by Köbel et al [24] and showed wild‐type expression in the first lesion (Figure 4A) and mutant expression in the second recurrence (Figure 4C), but p53 IHC was equivocal in the first recurrence (Figure 4B). Resected tumour 11 months after the second recurrence showed the known LIFR/PLAG1 and PIK3R1 clonal fingerprint and the TP53 p.R248Q (c.743G>A) mutation of the first recurrence.

Figure 3.

Ki‐67 IHC (×14 magnification of digital image) showing increasing expression of Ki‐67 over time (A, primary tumour; B, first recurrence; C, second recurrence).

Figure 4.

p53 IHC (×14 magnification of digital image) (Ventana BP53/11; BenchMark Ultra Stainer Module, Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA) showing (A) wild‐type, (B) equivocal, and (C) mutant expression of p53 in the primary tumour, first recurrence, and second recurrence, respectively.

Discussion

This report shows for the first time the chronological genetic steps of progression of SGPA to a malignant salivary gland tumour, accompanied by the occurrence of TP53 mutations. The two lesions with different clonal TP53 mutations probably represent two different recurrences from the same tumour, as multinodular recurrence is common. TP53 mutations have been reported as the most frequent mutations in salivary gland carcinomas in general, followed by abnormalities in the cyclin and PI3K pathways (including PIK3R1) [25].

All lesions showed the same LIFR/PLAG1 gene fusion, PIK3R1 mutation, and allelic imbalance pattern, revealing their origin from the primary SGPA. It is tempting to speculate that the combination of the LIFR/PLAG1 gene fusion and the PIK3R1 mutation with loss of the other allele were drivers for proliferation, whereas the additional TP53 mutations initiated the malignant transformation. Additional support for this comes from a mouse model with overexpression of Plag1 targeted to salivary gland and hyperactivation of the PI3K pathway by a conditional salivary gland Pten knockout mouse model, both of which resulted in pleomorphic adenoma formation [26, 27].

The occurrence of new TP53 mutations in the recurrences does not confirm a causal role for these mutations in malignant transformation as the specificity of TP53 mutation for this process is unknown. However, newly present TP53 mutations in genetically related subsequent recurrent tumours were accompanied histologically by malignancy; thus, a driver role seems likely, as TP53 is a well‐known tumour suppressor gene [28]. Loss of TP53 function is the most common molecular aberration in human malignancies and is involved in the initiation and progression of many malignant disorders. Based on the results from DNA mutation, SNP, and DNA amplicon coverage analyses, all three lesions are probably bi‐allelic for the TP53 locus (see supplementary material, Figure S3) and therefore have one functional intact TP53 allele. The identified TP53 mutations p.R248Q and p.Y220C, however, are known to exert a dominant‐negative effect leading to complete inactivation of TP53 without a second hit mutation (e.g. loss of the wild‐type TP53 allele) [29].

In this case, the first recurrence was not originally recognised as malignant, although the proliferation rate of 15% was relatively high [30]. In the second recurrence, morphology and proliferation rate were obvious clues for malignancy. In retrospect, p53 and Ki‐67 IHC might have raised the suspicion of malignancy, warranting molecular analysis.

Several aspects complicate salivary gland tumour diagnosis in general, such as their rarity and the wide morphological spectrum. Although SGPA is the most frequent primary salivary gland tumour, it is still a rare tumour (European standardised rate: 4.5/100,000 as opposed to 62/100,000 for breast cancer) [31]. Some of its characteristics can make correct diagnosis challenging, e.g. the morphological overlap with features of some of the 22 salivary gland carcinomas [20, 32]. Furthermore, malignant transformation of SGPA occurs only occasionally at a frequency of 6% of first RPAs [1]. And as shown in this case, malignant transformation can be difficult to recognise as the first recurrence already harboured a TP53 mutation but was not identified as malignant morphologically. This shows that, in the rare case of an RPA, molecular analysis can be of value in recognising early malignant transformation.

Clinically, the risks of infiltrative growth and malignant transformation have been important arguments for aggressive surgical treatment of RPA, which warrants the sacrifice of vital structures in selected cases. This case for the first time illustrates that malignant transformation of SGPA occurs and that molecular analysis can help to recognise malignancy. The combination of histology and molecular analysis can make a more solid diagnosis possible, which is imperative for appropriate clinical decision‐making.

Author contributions statement

MHV contributed conceptualisation, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, visualisation, and writing (original draft) of the manuscript. HM contributed investigation, visualisation, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. ItH was involved in investigation, visualisation, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. LRM contributed formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. AJMB and LES were involved in conceptualisation and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. SK contributed formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. WNMD was involved in conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, visualisation, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript. M‐LFvV contributed conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, visualisation, supervision, and writing (review and editing) of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Analysis with the Archer FusionPlex Sarcoma panel

Figure S2. NGS analysis of TP53 and PIK3R1 mutations in the primary tumour and the first and second recurrences

Figure S3. NGS analysis of allelic imbalances in the primary tumour and the first and second recurrences

Table S1. Custom‐made NGS panel information

No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- 1.Valstar MH, Andreasen S, Bhairosing PA, et al. Natural history of recurrent pleomorphic adenoma: implications on management. Head Neck 2020; 42: 2058–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Ridder M, Balm AJM, Smeele LE, et al. An epidemiological evaluation of salivary gland cancer in the Netherlands (1989‐2010). Cancer Epidemiol 2015; 39: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Röijer E, Nordkvist A, Ström AK, et al. Translocation, deletion/amplification, and expression of HMGIC and MDM2 in a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma. Am J Pathol 2002; 160: 433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Sebo TJ. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: pathologic analysis of 73 cases. Hum Pathol 2001; 36: 596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ihrler S, Guntinas‐Lichius O, Agaimy A, et al. Histological, immunohistological and molecular characteristics of intraductal precursor of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma support a multistep carcinogenic process. Virchows Arch 2017; 470: 601–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenman G. Fusion oncogenes in salivary gland tumors: molecular and clinical consequences. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7: S12–S19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell D, Myers JN, Rao PH, et al. t(3;8) as the sole chromosomal abnormality in a myoepithelial carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a putative progression event. Head Neck 2012; 35: E181–E183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deguchi H, Hamano H, Hayashi Y. c‐myc, ras p21 and p53 expression in pleomorphic adenoma and its malignant form of the human salivary glands. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993; 43: 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Palma S. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, with particular emphasis on early lesions. Head Neck Pathol 2013; 7: 68–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullerdiek J, Raabe G, Bartnitzke S, et al. Structural rearrangements of chromosome Nr 8 involving 8q12 – a primary event in pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland. Genetica 1987; 72: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kas K, Voz ML, Röijer E, et al. Promoter swapping between the genes for a novel zinc finger protein and beta‐catenin in pleiomorphic adenomas with t(3;8)(p21;q12) translocations. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voz ML, Aström AK, Kas K, et al. The recurrent translocation t(5;8)(p13;q12) in pleomorphic adenomas results in upregulation of PLAG1 gene expression under control of the LIFR promoter. Oncogene 1998; 16: 1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grünewald I, Vollbrecht C, Meinrath J, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing of parotid gland cancer uncovers genetic heterogeneity. Oncotarget 2015; 20: 18224–18237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson F, Andrén Y, Winnes M, et al. High‐resolution genomic profiling of adenomas and carcinomas of the salivary glands reveals amplification, rearrangement, and fusion of HMGA2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2009; 48: 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomes CC, Diniz MG, Orsine LA, et al. Assessment of TP53 mutations in benign and malignant salivary gland neoplasms. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordkvist A, Röijer E, Bang G, et al. Expression and mutation patterns of p53 in benign and malignant salivary gland tumors. Int J Oncol 2000; 16: 477–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ihrler S, Weiler C, Hirschmann A, et al. Intraductal carcinoma is the precursor of carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma and is often associated with dysfunctional p53. Histopathology 2007; 51: 362–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Righi PD, Li YQ, Deutsch M, et al. The role of the p53 gene in the malignant transformation of pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland. Anticancer Res 1994; 14: 2253–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiosea SI, Thompson LDR, Weinreb I, et al. Subsets of salivary duct carcinoma defined by morphologic evidence of pleomorphic adenoma, PLAG1 or HMGA2 rearrangements, and common genetic alterations. Cancer 2016; 122: 3136–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El‐Naggar A, Chan J, Takata T, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours (4th edn). IARC Press: Lyon, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antony J, Gopalan V, Smith RA, et al. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma: a comprehensive review of clinical, pathological and molecular data. Head Neck Pathol 2012; 6: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubbink HJ, Atmodimedjo PN, van Marion R, et al. Diagnostic detection of allelic losses and imbalances by next‐generation sequencing: 1p/19q co‐deletion analysis of gliomas. J Mol Diagn 2016; 18: 775–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Riet J, Krol NMG, Atmodimedjo PN, et al. SNPitty: an intuitive web application for interactive B‐allele frequency and copy number visualization of next‐generation sequencing data. J Mol Diagn 2018; 20: 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köbel M, Piskorz AM, Lee S, et al. Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res 2016; 2: 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato S, Elkin SK, Schwaederle M, et al. Genomic landscape of salivary gland tumors. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 25631–25645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Declercq J, Van Dyck F, Braem CV, et al. Salivary gland tumors in transgenic mice with targeted PLAG1 proto‐oncogene overexpression. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 4544–4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao Y, Liu H, Gao L, et al. Cooperation between Pten and Smad4 in murine salivary gland tumor formation and progression. Neoplasia 2018; 8: 764–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantovani F, Collavin L, Del Sal G. Mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cell. Cell Death Differ 2019; 26: 199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boettcher S, Miller PG, Sharma R, et al. A dominant‐negative effect drives selection of TP53 missense mutations in myeloid malignancies. Science 2019; 365: 599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tashiro T, Hirokawa M, Harada H, et al. Cell membrane expression of MIB‐1 in salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma. Histopathology 2002; 41: 559–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valstar MH, de Ridder M, van den Broek EC, et al. Salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma in the Netherlands: a nationwide observational study of primary tumor incidence, malignant transformation, recurrence, and risk factors for recurrence. Oral Oncol 2017; 66: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez‐Prera JC, Skálová A, Franchi A, et al. Pleomorphic adenoma: the great mimicker of malignancy. Histopathology 2020. 10.1111/his.14322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Analysis with the Archer FusionPlex Sarcoma panel

Figure S2. NGS analysis of TP53 and PIK3R1 mutations in the primary tumour and the first and second recurrences

Figure S3. NGS analysis of allelic imbalances in the primary tumour and the first and second recurrences

Table S1. Custom‐made NGS panel information