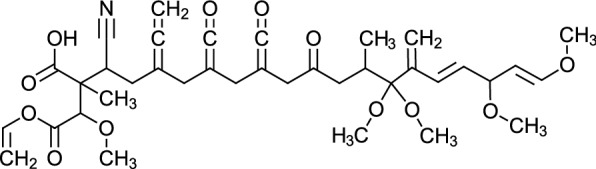

Abstract

Analysis of chemical graphs is becoming a major research topic in computational molecular biology due to its potential applications to drug design. One of the major approaches in such a study is inverse quantitative structure activity/property relationship (inverse QSAR/QSPR) analysis, which is to infer chemical structures from given chemical activities/properties. Recently, a novel two-phase framework has been proposed for inverse QSAR/QSPR, where in the first phase an artificial neural network (ANN) is used to construct a prediction function. In the second phase, a mixed integer linear program (MILP) formulated on the trained ANN and a graph search algorithm are used to infer desired chemical structures. The framework has been applied to the case of chemical compounds with cycle index up to 2 so far. The computational results conducted on instances with n non-hydrogen atoms show that a feature vector can be inferred by solving an MILP for up to , whereas graphs can be enumerated for up to . When applied to the case of chemical acyclic graphs, the maximum computable diameter of a chemical structure was up to 8. In this paper, we introduce a new characterization of graph structure, called “branch-height” based on which a new MILP formulation and a new graph search algorithm are designed for chemical acyclic graphs. The results of computational experiments using such chemical properties as octanol/water partition coefficient, boiling point and heat of combustion suggest that the proposed method can infer chemical acyclic graphs with around and diameter 30.

Keywords: QSAR/QSPR, Molecular design, Artificial neural network, Mixed integer linear programming, Enumeration of graphs

Background

In computational molecular biology, various types of data have been utilized, which include sequences, gene expression patterns, and protein structures. Graph structured data have also been extensively utilized, which include metabolic pathways, protein-protein interaction networks, gene regulatory networks, and chemical graphs. Much attention has recently been paid to the analysis of chemical graphs due to its potential applications to computer-aided drug design. One of the major approaches to computer-aided drug design is quantitative structure activity/property relationship (QSAR/QSPR) analysis, the purpose of which is to derive quantitative relationships between chemical structures and their activities/properties. Furthermore, inverse QSAR/QSPR has been extensively studied [1, 2], the purpose of which is to infer chemical structures from given chemical activities/properties. Inverse QSAR/QSPR is often formulated as an optimization problem to find a chemical structure maximizing (or minimizing) an objective function under various constraints.

In both QSAR/QSPR and inverse QSAR/QSPR, chemical compounds are usually represented as vectors of real or integer numbers, which are often called descriptors and correspond to feature vectors in machine learning. Using these chemical descriptors, various heuristic and statistical methods have been developed for finding optimal or nearly optimal graph structures under given objective functions [1, 3, 4]. Inference or enumeration of graph structures from a given feature vector is a crucial subtask in many of such methods. Various methods have been developed for this enumeration problem [5–8] and the computational complexity of the inference problem has been analyzed [9, 10]. On the other hand, enumeration in itself is a challenging task, since the number of molecules (i.e., chemical graphs) with up to 30 atoms (vertices) C, N, O, and S, may exceed [11].

As a new approach, artificial neural network (ANN) and deep learning technologies have recently been applied to inverse QSAR/QSPR. For example, variational autoencoders [12], recurrent neural networks [13, 14], and grammar variational autoencoders [15] have been applied. In these approaches, new chemical graphs are generated by solving a kind of inverse problems on neural networks that are trained using known chemical compound/activity pairs. However, the optimality of the solution is not necessarily guaranteed in these approaches. In order to guarantee the optimality mathematically, a novel approach has been proposed [16] for ANNs, using mixed integer linear programming (MILP).

Recently, a new framework has been proposed [17–19] by combining two previous approaches: efficient enumeration of tree-like graphs [5], and MILP-based formulation of the inverse problem on ANNs [16]. This combined framework for inverse QSAR/QSPR mainly consists of two phases. The first phase solves (I) Prediction Problem, where a feature vector f(G) of a chemical graph G is introduced and a prediction function on a chemical property is constructed with an ANN using a data set of chemical compounds G and their values a(G) of . The second phase solves (II) Inverse Problem, where (II-a) given a target value of the chemical property , a feature vector is inferred from the trained ANN so that is close to and (II-b) then a set of chemical structures such that is enumerated by a graph search algorithm. In (II-a) of the above-mentioned previous methods [17–19], an MILP is formulated for acyclic chemical compounds. Afterwards, Ito et al. [20] and Zhu et al. [21] designed a method of inferring chemical graphs with cycle index 1 and 2, respectively, by formulating a new MILP and using an efficient algorithm for enumerating chemical graphs with cycle index 1 [22] and cycle index 2 [23, 24]. The computational results conducted on instances with n non-hydrogen atoms show that a feature vector can be inferred for up to around whereas graphs can be enumerated for up to around .

In this paper, we present a new characterization of graph structure, called “branch-height.” Based on this, we can treat a class of acyclic chemical graphs with a structure that is topologically restricted but frequently appears in a chemical database, formulate a new MILP formulation that can handle acyclic graphs with a large diameter, and design a new graph search algorithm that generates acyclic chemical graphs with up to around 50 vertices. The results of computational experiments using such chemical properties as octanol/water partition coefficient, boiling point and heat of combustion suggest that the proposed method is much more useful than the previous method.

The paper is organized as follows. "Preliminary" section introduces some notions on graphs, a modeling of chemical compounds and a choice of descriptors. "A method for inferring chemical graphs" section reviews the framework for inferring chemical compounds based on ANNs and MILPs. "MILPs for chemical acyclic graphs with bounded branch-height" section introduces a new method of modeling acyclic chemical graphs and proposes a new MILP formulation that represents an acyclic chemical graph G with n vertices, where our MILP requires only O(n) variables and constraints when the branch-parameter k and the k-branch height in G (graph topological parameters newly introduced in this paper) is constant. "A new graph search algorithm" section describes the idea of our new dynamic programming type of algorithm that enumerates a given number of acyclic chemical graphs for a given feature vector. "Experimental results" section reports the results on some computational experiments conducted for chemical properties such as octanol/water partition coefficient, boiling point and heat of combustion. "Concluding remarks" section makes some concluding remarks. Appendix A provides the statistical distribution of structural features of acyclic chemical graphs in a chemical graph database. Appendices B and C describe the idea of our MILP formulation and the details of all variables and constraints in the MILP formulation, respectively. Appendix D presents descriptions of our new graph search algorithm.

Preliminary

This section introduces some notions and terminology on graphs, a modeling of chemical compounds and our choice of descriptors.

Let , and denote the sets of reals, integers and non-negative integers, respectively. For two integers a and b, let [a, b] denote the set of integers i with .

Graphs

A graph stands for a simple undirected graph, where an edge joining two vertices u and v is denoted by uv . The sets of vertices and edges of a graph H are denoted by V(H) and E(H), respectively. Let be a graph with a set V of vertices and a set E of edges. For a vertex , the set of neighbors of v in H is denoted by , and the degree of v is defined to be . The length of a path is defined to be the number of edges in the path. The distance between two vertices is defined to be the minimum length of a path connecting u and v in H. The diameter of H is defined to be the maximum distance between two vertices in H; i.e., . Denote by the length of a path P.

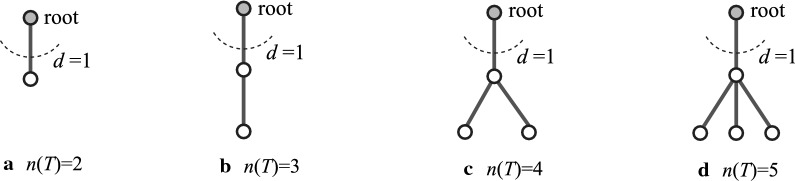

Centers of trees For a tree T with an even (resp., odd) diameter d, the center is defined to be the vertex v (resp., the adjacent vertex pair ) that situates in the middle of one of the longest paths, with length d. The center of each tree is uniquely determined.

Rooted trees A rooted tree is defined to be a tree where a vertex (or a pair of adjacent vertices) is designated as the root. Let T be a rooted tree, where for two adjacent vertices u and v, vertex u is called the parent of v if u is closer to the root than v is. The height of a vertex v in T is defined to be the maximum length of a path from v to a leaf u in the descendants of v, where for each leaf v in T. Figure 1a and b illustrate examples of trees rooted at the center.

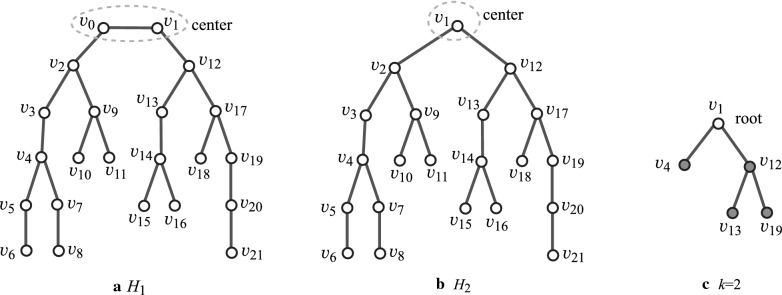

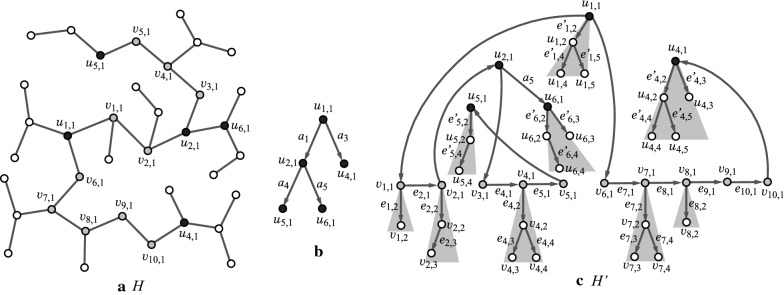

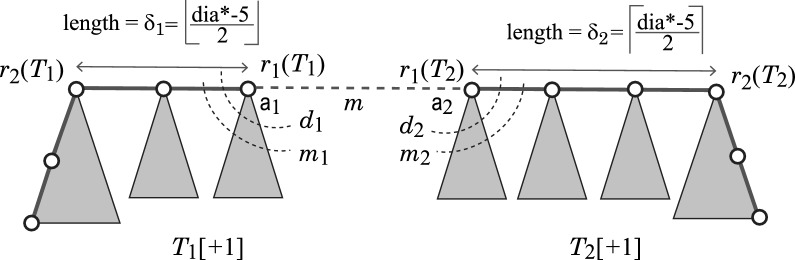

Fig. 1.

An illustration of rooted trees and a 2-branch-tree: a A tree with odd diameter 11; b A tree with even diameter 10; c The 2-branch-tree of

Degree-bounded trees For positive integers a, b and c with , let T(a, b, c) denote the rooted tree such that the number of children of the root is a, the number of children of each non-root internal vertex is b and the distance from the root to each leaf is c. We see that the number of vertices in T(a, b, c) is , and the number of non-leaf vertices in T(a, b, c) is . In the rooted tree T(a, b, c), we denote the vertices by with a breadth-first-search order, and denote the edge between a vertex with and its parent by , where and each vertex with is a non-leaf vertex. For each vertex in T(a, b, c), let denote the set of indices j such that is a child of , and denote the index j such that is the parent of when . Let be a set of ordered index pairs (i, j) of vertices and in T(a, b, c). We call proper if the next conditions hold:

For each pair of vertices and in T(a, b, c) such that is the parent of , there is a sequence of index pairs in such that and ; and

Each subtree of T(a, b, c) with is isomorphic to a subtree by a graph isomorphism with so that if for a pair then .

Note that a proper set is not necessarily unique.

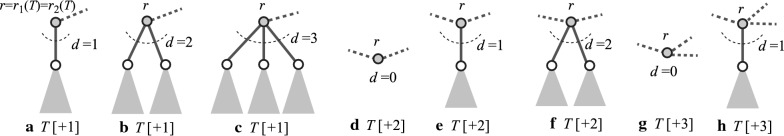

Branch-height in trees In this paper, we introduce “branch-height” of a tree as a new measure to the “agglomeration degree” of trees. We specify a non-negative integer k, called a branch-parameter to define branch-height. First we regard T as a rooted tree by choosing the center of T as the root. Figure 1a, b illustrate examples of rooted trees. We introduce the following terminology on a rooted tree T.

A leaf k-branch: A non-root vertex v in T such that .

A non-leaf k-branch: A non-root vertex v in T such that v has at least two children, and for each child u of v it holds that . We call a leaf or a non-leaf k-branch a k-branch. Figure 2a–c illustrate the k-branches of the rooted tree in Fig. 1b for and 3, respectively.

A k-branch-path: A path P in T that joins two vertices u and such that each of u and is the root or a k-branch and P does not contain the root or a k-branch as an internal vertex.

The k-branch-subtree of T: The subtree of T that consists of the edges in all k-branch-paths of T. We call a vertex (resp., an edge) in T a k-internal vertex (resp., a k-internal edge) if it is contained in the k-branch-subtree of T and a k-external vertex (resp., a k-external edge) otherwise. Let and (resp., and ) denote the sets of k-internal and k-external vertices (resp., edges) in T.

The k-branch-tree of T: The rooted tree obtained from the k-branch-subtree of T by replacing each k-branch-path with a single edge. Figure 1c illustrates the 2-branch-tree of the rooted tree in Fig. 1b. Notice that by our definitions, leaf k-branches and non-leaf k-branches are leaves and branching points in the k-branch-tree.

A k-fringe-tree: One of the connected components that consists of the edges not in the k-branch-subtree. Each k-fringe-tree contains exactly one vertex v in the k-branch-subtree, where is regarded as a tree rooted at v. Note that the height of any k-fringe-tree is at most k. Figure 2a–c illustrate the k-fringe-trees of the rooted tree in Fig. 1b for and 3, respectively.

The k-branch-leaf number : The number of leaf k-branches in T. For the trees , in Fig. 1a, b, it holds that , , and .

The k-branch height of T: The maximum number of k-branches along a path from the root to a leaf of T; i.e., is the height of the k-branch-tree (the maximum length of a path from the root to a leaf in ). For the example of trees , in Fig. 1a, b, it holds that , , and .

Fig. 2.

An illustration of the k-branches (depicted by gray circles), the k-branch-subtree (depicted by solid lines) and k-fringe-trees (depicted by dashed lines) of : a ; b ; c

Even though this paper deals exclusively with acyclic graphs, we formally introduce the k-branch height for chemical cyclic graphs (chemical graphs that contain at least one cycle). The core of a chemical cyclic graph G is defined to be the induced subgraph of G that consists of vertices in a cycle or the vertices in a path joining two cycles. A vertex in the core (not in the core) is called a core vertex (resp., a non-core vertex). The edges not in the core of a chemical cyclic graph G form a collection of trees T, which we call a non-core tree. Each non-core tree contains exactly one core vertex and is regarded as a tree rooted at the core vertex. The k-branch height of a chemical cyclic graph G is defined to be the maximum of k-branch heights over all non-core trees. We observe that most chemical graphs G with at most 50 non-hydrogen atoms satisfy . See Appendix A for a summary of statistical feature distribution of chemical graphs registered in the chemical database PubChem [25].

For convenient reference, we summarize the graph-related notation used throughout this paper in Table 1.

Table 1.

Graph-theoretic notation

| Symbol | Designation |

|---|---|

| General graph notation | |

| A graph H with a vertex set V and edge set E | |

| V(H) | The vertex set of a graph H |

| E(H) | The edge set of a graph H |

| The number of neighbors of a vertex v in a graph H | |

| The degree of a vertex v in a graph H | |

| The distance between two vertices u and v in a graph H | |

| The diameter of a graph H | |

| The length of a path P | |

| Branch-height in a tree T | |

| The set of internal vertices for a fixed branch parameter k | |

| The set of external vertices for a fixed branch parameter k | |

| The set of internal edges for a fixed branch parameter k | |

| The set of external edges for a fixed branch parameter k | |

| The k-branch-leaf number of T | |

| The k-branch height of T | |

Modeling of chemical compounds

We represent the graph structure of a chemical compound as a graph with labels on vertices and multiplicity on edges in a hydrogen-suppressed model. Let be a set of labels each of which represents a chemical element such as C (carbon), O (oxygen), N (nitrogen) and so on, where we assume that does not contain H (hydrogen). Let and denote the mass and valence of a chemical element , respectively. In our model, we use integer , , and assume that each chemical element has a unique valence .

We introduce a total order < over the elements in according to their mass values; i.e., we write for chemical elements with . A pair of two atoms and , , joined with a bond-multiplicity , where correspond to single, double, and triple bonds, respectively, is denoted by a tuple , called the adjacency-configuration of the atom pair. Choose a set of tuples such that . For a tuple , let denote the tuple . Set and , and .

We use a hydrogen-suppressed model because hydrogen atoms can be added at the final stage.

Let be a tuple of a graph , a function and a function , where and mean that a chemical element is assigned to a vertex v and a bond-multiplicity m is assigned to an edge e, respectively. For a notational convenience, we denote the sum of bond-multiplicities of edges incident to a vertex by

.

A tuple is called a chemical graph over and if the following holds:

-

(i)

H is connected;

-

(ii)

for each edge ; and

-

(iii)

for each vertex .

A chemical graph is called a “chemical acyclic graph” if the graph H is an acyclic graph. Similarly for other types of graphs for H.

We define the bond-configuration of an edge in a chemical graph G to be a tuple such that for the end-vertices u and v of e. Let denote the set of bond-configurations such that . We regard that .

In summary, we give the notation on modeling chemical compounds used throughout this paper in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notation adopted for modeling chemical compounds

| Symbol | Designation |

|---|---|

| A set of labels representing chemical elements | |

| Atomic mass of chemical element | |

| Valence of chemical element | |

| , | |

| A total order over labels in the set , indicating | |

| Adjacency configuration for an atom pair, , | |

| For an adjacency configuration , | |

| Set of adjacency configurations with | |

| Set of adjacency configurations | |

| Set of adjacency configurations, | |

| A mapping of atom labels in to graph vertices | |

| A mapping of integers in [1, 3] to graph edges, overloaded as for vertices in a graph H | |

| Set of bond-configurations |

Descriptors

In our method, we use only graph-theoretical descriptors for defining a feature vector, which facilitates our design of an algorithm for constructing graphs. Given a chemical acyclic graph , we define a feature vector f(G) that consists of the following 11 kinds of descriptors. We choose an integer as a branch-parameter.

General chemical graph descriptors

n(G): the number |V| of vertices.

: the diameter of H divided by .

: the average of atoms in G.

: the number of hydrogen atoms to be added to G.

Descriptors for vertices of certain degree

: the number of -internal/-external vertices of degree i in H, where the bond-multiplicity of edges incident to a vertex v is ignored in the degree of v.

Descriptors for branch-leaf number and branch-height

: the -branch-leaf number of G.

: the -branch height of G.

Descriptors for vertex labels

: the number of -internal/-external vertices with chemical element .

Descriptors for the number of bonds

, , : the number of -internal/-external edges with bond-multiplicity m.

Descriptors for adjacency-configurations

, , : the number of -internal/-external edges with adjacency-configuration (i.e., and ) in G.

Descriptors for bond-configurations

, , : the number of -internal/-external edges with bond-configuration (i.e., and ) in G.

Note that

The number K of descriptors in our feature vector is . Note that the above K descriptors are not independent in the sense that some descriptors depend on the combination of other descriptors. For example, descriptor can be determined by .

A method for inferring chemical graphs

Framework for the Inverse QSAR/QSPR

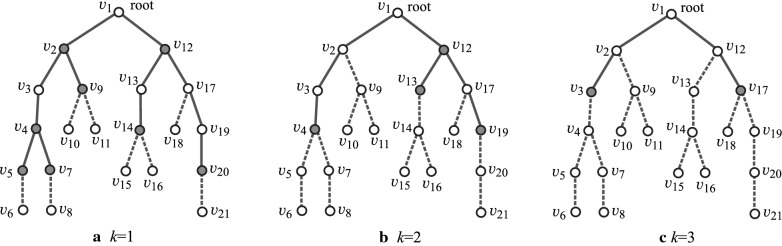

We review the framework that solves the inverse QSAR/QSPR by using MILPs [20, 21], which is illustrated in Fig. 3. For a specified chemical property such as boiling point, we denote by a(G) the observed value of the property for a chemical compound G. As the first phase, we solve (I) Prediction Problem with the following three steps.

Fig. 3.

a–c An illustration of Phase 1: a Stage 1 for preparing a data set for a graph class and a specified chemical property ; b Stage 2 for introducing a feature function f with descriptors; c Stage 3 for constructing a prediction function with an ANN ; d–e An illustration of Phase 2: (d) Stage 4 for formulating an MILP and finding a feasible solution of the MILP for a target value so that (possibly detecting that no target graph exists); (e) Stage 5 for enumerating graphs such that

Phase 1.

Stage 1: Let be a set of chemical graphs. For a specified chemical property , choose a class of graphs such as acyclic graphs or monocyclic graphs. Prepare a data set such that the value of each chemical graph , is available. Set reals so that , .

Stage 2: Introduce a feature function for a positive integer K. We call f(G) the feature vector of , and call each entry of a vector f(G) a descriptor of G.

Stage 3: Construct a prediction function with an ANN that, given a vector in , returns a real number in the range so that takes a value nearly equal to a(G) for many chemical graphs in . See Fig. 3a–c for an illustration of Stages 1, 2, and 3 in Phase 1.

In this paper, we use the range-based method to define an applicability domain (AD) [26] to our inverse QSAR/QSPR. Set and to be the minimum and maximum values of the j-th descriptor in , respectively, over all graphs , , where we possibly normalize some descriptors such as , which is normalized with . Define our AD to be the set of vectors such that for the variable of each j-th descriptor, .

In the second phase, we try to find a vector from a target value of the chemical propery such that . Based on the method due to Akutsu and Nagamochi [16], Chiewvanichakorn et al. [18] showed that this problem can be formulated as an MILP. By including a set of linear constraints such that into their MILP, we obtain the next result.

Theorem 1

([20, 21]) Let be an ANN with a piecewise-linear activation function for an input vector denote the number of nodes in the architecture and denote the total number of break-points over all activation functions. Then there is an MILP that consists of variable vectors , , and an auxiliary variable vector for some integer and a set of constraints on these variables such that: if and only if there is a vector feasible to .

See Appendix “Upper and lower bounds on descriptors” for the set of constraints to define our AD in the MILP in Theorem 1.

A vector is called admissible if there is a chemical graph such that [17]. Let denote the set of admissible vectors . To ensure that a vector inferred from a given target value becomes admissible, we introduce a new vector variable for an integer q. For the class of chemical acyclic graphs, Azam et al. [17] introduced a set of new constraints with a new vector variable for an integer q so that

A feasible solution of a new MILP for a target value delivers a vector with , and

A vector that represents a chemical acyclic graph .

Afterwards, for the classes of chemical graphs with cycle index 1 and 2, Ito et al. [17] and Zhu et al. [21] presented such a set of constraints so that a vector in a feasible solution of a new MILP can represent a chemical graph in the class , respectively.

As the second phase, we solve (II) Inverse Problem for the inverse QSAR/QSPR by treating the following inference problems.

(II-a) Inference of Vectors

Input: A real with .

Output: Vectors and such that and forms a chemical graph with .

(II-b) Inference of Graphs

Input: A vector .

Output: All graphs such that .

The second phase consists of the next two steps.

Phase 2.

Stage 4: Formulate Problem (II-a) as the above MILP based on and . Find a feasible solution of the MILP such that

and .

The second requirement may be replaced with inequalities for a tolerance

Stage 5: To solve Problem (II-b), enumerate all (or a specified number) of graphs such that for the inferred vector . See Fig. 3d, e for an illustration of Stages 4 and 5 in Phase 2.

In practical applications, there would be many criteria that a target chemical compound needs to satisfy rather than a single chemical property , such as stability and synthesizability. The above five steps in the framework are rather schematic in the sense that it would be necessary to adjust several settings in each stage in order to find a collection of chemical graphs that meet many of those criteria after a repeated application of the framework. For example, we can include in an MILP formulation in Stage 4 additional conditions such as lower and upper bounds on the frequency of adjacency-configurations and extra requirements on substructures of a target chemical graph as long as these conditions can be expressed as linear constraints with integer/real variables. Also an efficient algorithm in Stage 5 can quickly offer a large number of isomers of the same feature vectors, to which we can apply a further screening to choose promising candidates for chemical graphs.

Our target graph class

In this paper, we choose a branch-parameter and define a class of chemical acyclic graphs G such that

The maximum degree in G is at most 4;

The k-branch height is bounded for a specified branch-parameter k; and

The size of each k-fringe-tree in G is bounded.

The reason why we restrict ourselves to the graphs in is that this class covers a large part of the acyclic chemical compounds registered in the chemical database PubChem. See Appendix A for a summary of the statistical features of the chemical graphs in PubChem in terms of k-branch height and the size of 2-fringe-trees. According to this, over 55% (resp., 99%) of acyclic chemical compounds with up to 100 non-hydrogen atoms in PubChem have the maximum degree 3 (resp., 4); and nearly 87% (resp., 99%) of acyclic chemical compounds with up to 50 non-hydrogen atoms in PubChem have the 2-branch height at most 1 (resp., 2). This implies that is sufficient to cover most of chemical acyclic graphs. For , over 92% of 2-fringe-trees of chemical compounds with up to 100 non-hydrogen atoms in PubChem obey the following size constraint:

| 1 |

We formulate an MILP in Stage 4 that, given a target value , infers a vector with and a chemical acyclic graph with . We here specify some of the features of a graph such as the number of non-hydrogen atoms in order to control the graph structure of target graphs to be inferred and to simplify MILP formulations. In this paper, we specify the following features on a graph : a set of chemical elements, a set of adjacency-configurations, the maximum degree, the number of non-hydrogen atoms, the diameter, the k-branch height and the k-branch-leaf number for a branch-parameter k.

More formally, given specified integers , , , , , other than and , let denote the set of acyclic graphs H such that

The maximum degree of a vertex in H is at most 3 when (or equal to 4 when ),

The number n(H) of vertices in H is ,

The diameter of H is ,

The -branch height is ,

The -branch-leaf number is and

(1) holds.

To design Stage 4 for our class , we formulate an MILP that infers a chemical graph with for a given specification . The details will be given in "MILPs for chemical acyclic graphs with bounded branch-height" section and Appendix C.

Design of Stage 5, i.e., generating chemical graphs that satisfy for a given feature vector is still challenging for a relatively large instance with size . There have been proposed algorithms for generating chemical graphs in Stage 5 for the classes of graphs with cycle index 0 to 2 [5, 22–24]. All of these are designed based on the branch-and-bound method and can generate a target chemical graph with size . To break this barrier, we newly employ the dynamic programming method for designing an algorithm in Stage 5 in order to generate a target chemical graph with size . For this, we further restrict the structure of acyclic graphs G so that the number of leaf 2-branches is at most 3. Among all acyclic chemical compounds with up to 50 non-hydrogen atoms in the chemical database PubChem, the ratio of the number of acyclic chemical compounds G with (resp., ) is 78% (resp., 95%). See "A new graph search algorithm" section and Appendix D for the details on the new algorithm in Stage 5.

To conclude the description of the target graph class to be inferred by the inverse QSAR/QSPR framework developed in this paper, we summarize the global parameters in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fixed parameters of target graphs

| Symbol | Designation |

|---|---|

| A set of atom labels | |

| A set of adjacency configurations | |

| Number of vertices | |

| Maximum vertex degree, at most 3 and exactly 4, for and , respectively | |

| Graph diameter | |

| Branch parameter | |

| -branch height | |

| -branch-leaf number |

MILPs for chemical acyclic graphs with bounded branch-height

In this section, we describe an idea of formulating an MILP to infer a chemical acyclic graph G in the class for a given specification defined in the previous section. Please refer to Table 3 for a summary of the parameters that we assume to be fixed for a target graph.

Scheme graphs

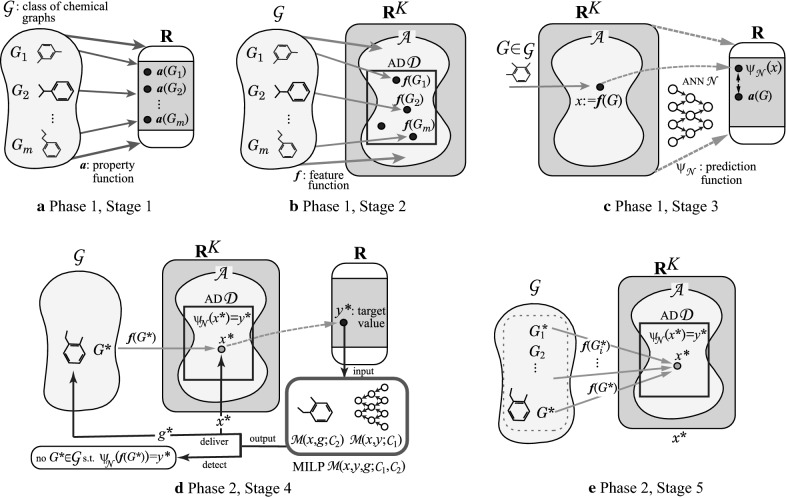

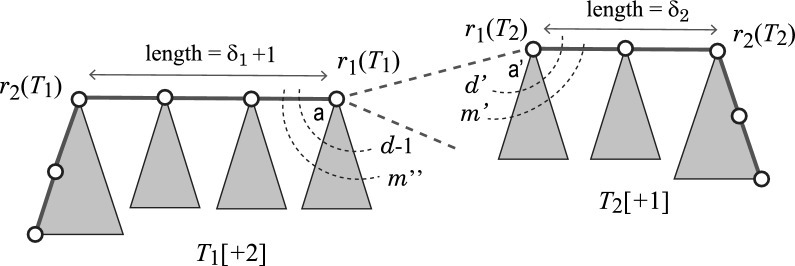

Our new idea of constructing an acyclic graph H is as follows. See a rooted tree in Fig. 4a.

From the tree , we first choose a subtree T including the root . We use T as the -branch-tree of H.

Next, we choose some edges in the tree T and replace each of the edges with a path between vertices and . Let denote the resulting tree. We use as the -branch-subtree of H.

Finally, we append to the tree rooted trees with height at most k as the -fringe-trees of H. The resulting tree is a required rooted tree H.

Fig. 4.

An illustration of scheme graph with , , , and , where the vertices in (resp., in ) are depicted with black (resp., gray) circles: a A base-tree and a link-path are joined with directed edges between them; b A tree rooted at a vertex ; c A tree rooted at a vertex

In our MILP, we prepare a binary variable for each of the vertices and edges in so that a subtree T of can be selected as one of the combinations of these binary values.

To represent a replacement of an edge e with a path in our MILP, we introduce a path of a sufficiently large length , and a set F of directed edges between the vertices in and as shown in Fig. 4a. We also introduce a binary variable for each of the vertices and edges in and F in our MILP. When an edge is replaced with a path , we select an edge from to a vertex in and an edge from a vertex so that the edges and and the subpath of form a path . Such a path can be selected as one of the combinations of these binary values. To append rooted trees to tree , we prepare a rooted tree with a sufficiently large size at each vertex in and and introduce a binary variable for each of the vertices and edges in these rooted trees in our MILP. A rooted subtree from each of such rooted trees as a -fringe-tree can be selected as one of the combinations of these binary values.

We call the graph that consists of all the above graphs , and the edge set F and the set of rooted trees at the vertices in and a scheme graph .

Figure 5a illustrates an acyclic graph H with , , and , where the maximum degree of a vertex is 3. Figure 5b illustrates the 2-branch-tree of the acyclic graph H in Fig. 5a. Figure 5c illustrates a subgraph of the scheme graph such that is isomorphic to the acyclic graph H in Fig. 5a.

Fig. 5.

An illustration of selecting a subgraph H from the scheme graph : a An acyclic graph with , , , , and , where the labels of some vertices indicate the corresponding vertices in the scheme graph ; b The -branch-tree of H for ; c An acyclic graph selected from as a graph that is isomorphic to H in (a)

In this paper, we obtain the following result.

Theorem 2

Letbe a set of chemical elements,be a set of adjacency-configurations, where, and. Given non-negative integers,,,,and, there is an MILPthat consists of variable vectorsandfor an integerand a setof constraints onxandgwith sizesuch that:is feasible toif and only ifforms a chemical acyclic graphsuch thatand.

Note that our MILP requires only variables and constraints when the branch-parameter , the -branch height and are constant.

See Appendices B and C for the details of the MILP formulation and the set of all variables and constraints in the MILP formulation, respectively.

A new graph search algorithm

Previous methods of inferring chemical graphs [17–19] use a graph search algorithm based on the branch-and-bound algorithm proposed by Fujiwara et al. [5], where an enormous number of chemical graphs are constructed by repeatedly appending and removing a vertex one by one until a target chemical graph is constructed. Their algorithm cannot generate even one acyclic chemical graph when n(G) is larger than around 20.

This section introduces a new dynamic programming method for designing an algorithm in Stage 5. We consider the following aspects:

Treat acyclic graphs with a certain limited structure that frequently appears among chemical compounds registered in the chemical database; and

Instead of manipulating acyclic graphs directly, first compute the frequency vectors (sub-vectors of the feature vectors , see Appendix D) of subtrees of all target acyclic graphs and then construct a limited number of target graphs G from the process of computing the vectors.

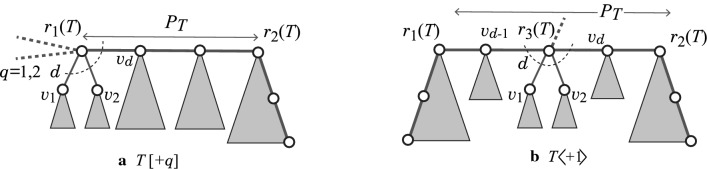

In (a), we choose a branch-parameter and treat acyclic graphs G that have a small 2-branch number such as and satisfy the size constraint (1) on 2-fringe-trees. Figure 6a, b illustrate chemical acyclic graphs G with and , respectively.

Fig. 6.

An illustration of chemical acyclic graphs G with diameter and : a A chemical acyclic graph G with two leaf 2-branches and ; b A chemical acyclic graph G with three leaf 2-branches and

We design a method in (b) based on the mechanism of dynamic programming in the following way. Define a frequency vector of each chemical rooted tree T to be a vector that consists of the frequency of each chemical element , each adjacency-configuration , each bond-configuration , and each degree in T. We are given a vector that is the frequency vector of a chemical acyclic graph G to be inferred.

We first construct a set of chemical rooted trees with height at most and compute the frequency vector of each chemical rooted tree to obtain the set of frequency vectors . Note that a large number of chemical rooted trees maps to the same frequency vector and the size is considerably smaller than the size .

We next combine two chemical rooted trees to construct a chemical tree by joining their roots and with an edge of a bond-multiplicity m, as illustrated in Fig. 6a. In fact, we compute only the feature vector of such a tree without directly treating the graph structures of , and . For this, we add two frequency vectors together with an additional term from the bond-multiplicity m to obtain the frequency vector of such a tree . Given such a vector , we can actually construct a chemical tree with by choosing trees and combining them with an edge of bond-multiplicity m.

Our algorithm for generating a chemical acyclic graph G with continues to compute a set of frequency vectors of chemical trees that can be obtained by combining p trees in for each . Finally, we find a vector pair with and such that a vector with , and a bond-multiplicity m is equal to the given vector ; i.e., a chemical acyclic graph G with is obtained by joining chemical trees and with with an edge of bond-multiplicity m.

With a slight modification, the algorithm can generate a chemical acyclic graph G with .

Appendix D presents the details of our new algorithms for generating acyclic graphs G with .

Experimental results

We implemented our method of Stages 1 to 5 for inferring chemical acyclic graphs and conducted experiments to evaluate the computational efficiency for three chemical properties : octanol/water partition coefficient (Kow), boiling point (Bp) and heat of combustion (Hc). We executed the experiments on a PC with Two Intel Xeon CPUs E5-1660 v3 @3.00GHz, 32 GB of RAM running under OS: Ubuntu 14.04.6 LTS. We show 2D drawings of some of the inferred chemical graphs, where ChemDoodle version 10.2.0 was used for constructing the drawings.

Results on Phase 1. We implemented Stages 1, 2, and 3, in Phase 1 as follows.

Stage 1. We set a graph class to be the set of all chemical acyclic graphs, and set a branch-parameter to be 2. For each property Kow, Bp, Hc, we first select a set of chemical elements and then collected a data set on chemical acyclic graphs over the set of chemical elements provided by the Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) of PubChem. To construct the data set, we eliminated chemical compounds that have at most three carbon atoms or contain a charged element such as or an element whose valence is different from our setting of valence function .

Table 4 shows the size and range of data sets that we prepared for each chemical property in Stage 1, where we denote the following:

: one of the chemical properties Kow, Bp and Hc;

: the set of selected chemical elements (hydrogen atoms are added at the final stage);

: the size of data set over for property ;

: the number of different adjacency-configurations over the compounds in ;

: the minimum and maximum number n(G) of non-hydrogen atoms over the compounds G in ;

: the minimum and maximum numbers of leaf 2-branches over the compounds G in ;

: the minimum and maximum values of the 2-branch height over the compounds G in ; and

: the minimum and maximum values of a(G) for over compounds G in .

Table 4.

Results of Stage 1 in Phase 1

| Kow | C,O,N | 216 | 10 | [4, 28] | [0, 2] | [0, 4] | [− 4.2, 8.23] |

| Bp | C,O,N | 172 | 10 | [4, 26] | [0, 1] | [0, 3] | [− 11.7, 404.84] |

| Hc | C,O,N | 128 | 6 | [4, 26] | [0, 1] | [0, 2] | [1346.4, 13304.5] |

Stage 2. We used a feature function f that consists of the descriptors defined in “Descriptors” section.

Stage 3. We used scikit-learn version 0.21.6 with Python 3.7.4 to construct ANNs where the tool and activation function are set to be MLPRegressor and ReLU, respectively. We tested several different architectures of ANNs for each chemical property. To evaluate the performance of the resulting prediction function with cross-validation, we partition a given data set into five subsets , randomly, where is used for a training set and is used for a test set in five trials . For a set of observed values and a set of predicted values, we define the coefficient of determination to be , where . Table 5 shows the results on Stages 2 and 3, where

K: the number of descriptors for the chemical compounds in data set for property ;

Activation: the choice of activation function;

Architecture: (a, b, 1) consists of an input layer with a nodes, a hidden layer with b nodes and an output layer with a single node, where a is equal to the number K of descriptors;

L-time: the average time (in seconds) to construct ANNs for each trial;

test (ave.): the average of coefficient of determination over the five tests; and

test (best): the largest value of coefficient of determination over the five test sets.

From Table 5, we see that the execution of Stage 3 was successful, where the average of test is over 0.9 for all three chemical properties.

Table 5.

Results of Stages 2 and 3 in Phase 1

| K | Activation | Architecture | L-Time | test (ave.) | test (best) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 76 | ReLU | (76, 10, 1) | 2.12 | 0.901 | 0.951 |

| Bp | 76 | ReLU | (76, 10, 1) | 26.07 | 0.935 | 0.965 |

| Hc | 68 | ReLU | (68, 10, 1) | 234.06 | 0.924 | 0.988 |

For each chemical property , we selected the ANN that attained the best test score among the five ANNs to formulate an MILP which will be used in Phase 2.

Results on Phase 2. We implemented Stages 4 and 5 in Phase 2 as follows.

Stage 4. In this step, we solve the MILP formulated based on the ANN obtained in Phase 1. To solve an MILP in Stage 4, we use CPLEX version 12.10. In our experiment, we choose a target value and fix or bound some descriptors in our feature vector as follows:

Set the 2-leaf-branch number to be each of 2 and 3;

Fix the instance size to be each integer in ;

Set the diameter be one of the integers in .

Set the maximum degree for and for ;

For each instance size , test a target value for each chemical property Kow, Bp, Hc.

Based on the above setting, we generated six instances for each instance size . We set in Stage 4.

Tables 6, 7 (resp., Tables 8, 9) show the results on Stage 4 for (resp., ), where we denote the following:

: a target value in for a property ;

: a specified number of vertices in ;

: a specified diameter in ;

IP-time: the time (sec.) to an MILP instance to find vectors and .

We observe that most of the MILP instances with , and (resp., , and ) are solved within one minute (resp., in a few minutes). The previously most efficient MILP formulation for inferring chemical acyclic graphs due to Zhang et al. [19] could solve instances with a relatively small diameter of for the case of and and for the case of and . Our new MILP formulation on chemical acyclic graphs with bounded 2-branch height considerably improved the tractable size of chemical acyclic graphs in Stage 4 for the inference problem (II-a).

Table 6.

Results of Stages 4 and 5 for , and

| IP-time | FP | G-LB | G | G-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 4 | 26 | 11 | 3.95 | 11,780 | 100 | 0.91 | |

| 5 | 32 | 13 | 4.81 | 216 | 100 | 10.64 | ||

| 7 | 38 | 16 | 7.27 | 19,931 | 100 | 48.29 | ||

| 8 | 44 | 18 | 9.33 | 241,956 | 100 | 119.01 | ||

| 9 | 50 | 20 | 21.57 | 58,365 | 100 | 110.38 | ||

| Bp | 440 | 26 | 11 | 2.09 | 22,342 | 100 | 2.9 | |

| 550 | 32 | 13 | 3.94 | 748 | 100 | 3.77 | ||

| 660 | 38 | 16 | 6.4 | 39,228 | 100 | 151.25 | ||

| 770 | 44 | 18 | 7.21 | 138,076 | 100 | 182.66 | ||

| 880 | 50 | 20 | 9.49 | 106,394 | 100 | 217.18 | ||

| Hc | 13000 | 26 | 11 | 2.94 | 12 | 12 | 0.04 | |

| 16500 | 32 | 13 | 7.67 | 2722 | 100 | 0.31 | ||

| 20000 | 38 | 16 | 10.5 | 1830 | 100 | 1.06 | ||

| 23000 | 44 | 18 | 13.62 | 12,336 | 100 | 142.02 | ||

| 25000 | 50 | 20 | 15.1 | 136,702 | 100 | 22.26 |

Table 7.

Results of Stages 4 and 5 for , and

| IP-time | FP | G-LB | G | G-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 4 | 26 | 16 | 16.21 | 4198 | 100 | 1.18 | |

| 5 | 32 | 20 | 24.74 | 1650 | 100 | 0.69 | ||

| 7 | 38 | 23 | 38.88 | 154,408 | 100 | 67.31 | ||

| 8 | 44 | 27 | 38.73 | 1,122,126 | 100 | 660.37 | ||

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 31.59 | 690,814 | 100 | 238.02 | ||

| Bp | 440 | 26 | 16 | 12.44 | 8156 | 100 | 2.74 | |

| 550 | 32 | 20 | 23.22 | 38,600 | 100 | 12.72 | ||

| 660 | 38 | 23 | 20.62 | 52,406 | 100 | 197.89 | ||

| 770 | 44 | 27 | 50.55 | 23,638 | 100 | 244.56 | ||

| 880 | 50 | 30 | 48.37 | 40,382 | 100 | 884.99 | ||

| Hc | 13000 | 26 | 16 | 23.26 | 249 | 100 | 0.06 | |

| 16500 | 32 | 20 | 44.2 | 448 | 100 | 0.63 | ||

| 20000 | 38 | 23 | 96.02 | 3330 | 100 | 15.16 | ||

| 23000 | 44 | 27 | 82.34 | 43,686 | 100 | 152.96 | ||

| 25000 | 50 | 30 | 83.81 | 311,166 | 100 | 287.95 |

Table 8.

Results of Stages 4 and 5 for , and

| IP-time | FP | G-LB | G | G-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 4 | 26 | 11 | 3.1 | 511 | 100 | 14.31 | |

| 5 | 32 | 13 | 4.72 | 3510 | 100 | 851.21 | ||

| 7 | 38 | 16 | 5.82 | 11,648 | 100 | 612.86 | ||

| 8 | 44 | 18 | 9.69 | 17,239 | 100 | 703.92 | ||

| 9 | 50 | 20 | 22.53 | 60,792 | 100 | 762.17 | ||

| Bp | 440 | 26 | 11 | 3.01 | 66 | 66 | 902.77 | |

| 550 | 32 | 13 | 4.29 | 308 | 100 | 2238.62 | ||

| 660 | 38 | 16 | 5.86 | 303 | 100 | 3061.11 | ||

| 770 | 44 | 18 | 14.39 | 19,952 | 100 | 678.26 | ||

| 880 | 50 | 20 | 10.39 | 17,993 | 100 | 4151.07 | ||

| Hc | 13000 | 26 | 11 | 3.05 | 340 | 100 | 1.57 | |

| 16500 | 32 | 13 | 5.81 | 600 | 100 | 921.55 | ||

| 20000 | 38 | 16 | 15.67 | 18,502 | 100 | 1212.54 | ||

| 23000 | 44 | 18 | 21.15 | 5064 | 100 | 1279.95 | ||

| 25000 | 50 | 20 | 31.90 | 41,291 | 100 | 668.5 |

Table 9.

Results of Stages 4 and 5 for , and

| IP-time | FP | G-LB | G | G-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 4 | 26 | 16 | 9.94 | 100 | 100 | 6.73 | |

| 5 | 32 | 20 | 16.58 | 348 | 100 | 3400.74 | ||

| 7 | 38 | 23 | 33.71 | 17,557 | 100 | 2652.38 | ||

| 8 | 44 | 27 | 34.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | >2 hours | |

| 9 | 50 | 30 | 68.74 | 80,411 | 100 | 6423.85 | ||

| Bp | 440 | 26 | 16 | 14.16 | 150 | 100 | 29.72 | |

| 550 | 32 | 20 | 18.94 | 305 | 100 | 2641.9 | ||

| 660 | 38 | 23 | 21.15 | 1155 | 100 | 4521.66 | ||

| 770 | 44 | 27 | 25.6 | 1620 | 100 | 175.2 | ||

| 880 | 50 | 30 | 63.22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | >2 hours | |

| Hc | 13000 | 26 | 16 | 31.87 | 12 | 12 | 0.66 | |

| 16500 | 32 | 20 | 41.03 | 392 | 100 | 2480.34 | ||

| 20000 | 38 | 23 | 48.48 | 630 | 100 | 105.59 | ||

| 23000 | 44 | 27 | 143.75 | 341 | 100 | 5269.1 | ||

| 25000 | 50 | 30 | 315.91 | 10,195 | 100 | 5697.08 |

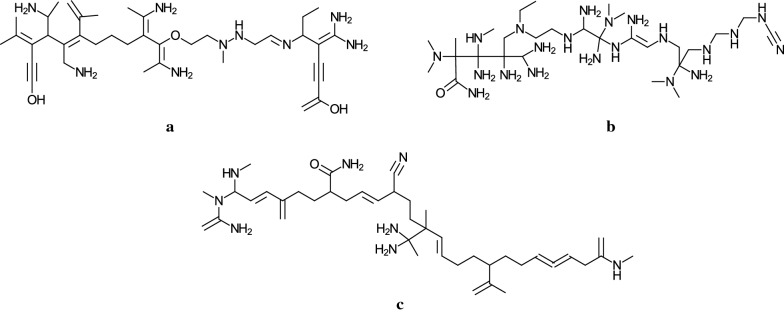

Figure 7a–c illustrate some chemical acyclic graphs G with obtained in Stage 4 by solving an MILP. Remember that these chemical graphs obey the AD defined in Appendix A.

Fig. 7.

An illustration of chemical acyclic graphs G with , and obtained in Stage 4 by solving an MILP: a , ; b , ; c ,

Figure 8a–c illustrate some chemical acyclic graphs G with obtained in Stage 4 by solving an MILP.

Fig. 8.

An illustration of chemical acyclic graphs G with , and obtained in Stage 4 by solving an MILP: a , ; b , ; c ,

Stage 5. In this stage, we execute our new graph search algorithms for generating target graphs with for a given feature vector obtained in Stage 4.

We introduce a time limit of 10 minutes for each iteration h in Step 2 and an execution of Steps 1 and 3 for (resp., each iteration h in Steps 2 and 3 and in Step 4 and an execution of Steps 1 and 5 for ). In the last step, we choose at most 100 feasible vector pairs and generate a target graph from each of these feasible vector pairs. We also impose an upper bound on the size of a vector set that we maintain during an execution of the algorithm. We executed the algorithm for each of the three bounds until a feasible vector pair is found or the running time exceeds a global time limitation of two hours.

When no feasible vector pair is found by the graph search algorithms, we output the target graph constructed from the vector in Stage 4.

Tables 6, 7 (resp., Tables 8, 9) show the results of Stage 5 for (resp., ), where we denote the following:

FP: the number of feasible vector pairs obtained by an execution of the graph search algorithm for a given feature vector ;

G-LB: a lower bound on the number of all target graphs for a given feature vector ;

G: the number of all (or up to 100) chemical acyclic graphs G such that (where at least one such graph G has been found from the vector in Stage 4);

G-time: the running time (sec.) to execute Stage 5 for a given feature vector , where “> 2 hours” means that the running time exceeds two hours.

Previously, an instance of chemical acyclic graphs with size up to 16 was solved in Stage 5 by Azam et al. [17]. For the classes of chemical graphs with cycle index 1 and 2, the maximum size of instances solved in Stage 5 by Ito et al. [17] and Zhu et al. [21] was around 18 and 15, respectively. Our new algorithm based on dynamic programming solves instances with . In our experiments, we also computed a lower bound G-LB on the number of target graphs. We observe that there are over or target graphs in some cases. Remember that these lower bounds are computed without actually generating each target graph one by one. So when a lower bound is enormously large, this would suggest that we may need to impose some more constraints on the structure of graphs or the range of descriptors to narrow a family of target graphs to be inferred.

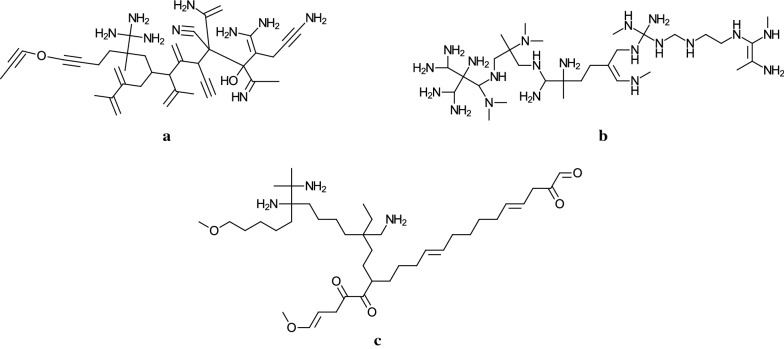

An additional experiment We also conducted some additional experiment to demonstrate that our MILP-based method is flexible to control conditions on inference of chemical graphs. In Stage 3, we constructed an ANN for each of the three chemical properties Kow, Bp, Hc, and formulated the inverse problem of each ANN as an MILP . Since the set of descriptors is common to all three properties Kow, Bp and Hc, it is possible to infer a chemical acyclic graph G that satisfies a target value for each of the three properties at the same time (if one exists). We specify the size of graph so that , , and , and set target values with , and in an MILP that consists of the three MILP , and . The MILP was solved in 18930 seconds and we obtained a chemical acyclic graph G illustrated in Fig. 9. We continued to execute Stage 5 for this instance to generate more target graphs . Table 10 shows that 100 target graphs are generated by our new dynamic programming algorithm.

Fig. 9.

An illustration of a chemical acyclic graph G inferred for three chemical properties Kow, Bp and Hc simultaneously, where , and , , , , and

Table 10.

Results of Stages 4 and 5 for , , and

| IP-time | FP | G-LB | G | G-time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kow | 4 | 50 | 25 | 18930.46 | 117,548 | 100 | 423.53 | |

| Bp | 400 | |||||||

| Hc | 1300 |

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we introduced a new measure, branch-height of a tree, and showed that many chemical compounds in the chemical database have a simple structure where the number of 2-branches is small. Based on this, we proposed a new method of applying the framework for inverse QSAR/QSPR [17–19] to the case of acyclic chemical graphs where Azam et al. [17] inferred chemical graphs with around 20 non-hydrogen atoms and Zhang et al. [19] solved an MILP of inferring a feature vector for an instance with diameter 9. In our method, we formulated a new MILP in Stage 4 specialized for acyclic chemical graphs with a small branch number and designed a new graph search algorithm in Stage 5 that computes frequency vectors of graphs in a dynamic programming scheme.

We implemented our new method and conducted some experiments on chemical properties such as octanol/water partition coefficient, boiling point and heat of combustion.

The resulting method improved the performance so that chemical graphs with around 50 non-hydrogen atoms and around diameter 30 can be inferred. Since there are many acyclic chemical compounds having large diameters, this is a significant improvement.

It is left as a future work to design MILPs and graph search algorithms based on the new idea of the paper for classes of graphs with a higher rank. Recently, a method for inferring a chemical cyclic graph with any rank has been designed by Akutsu and Nagamochi [27] based on the ideas in this paper. The method is also designed so that a target chemical graph to be inferred can be specified in a more flexible way, where we can include a prescribed substructure of graphs such as a benzene ring into a target chemical graph while imposing constraints on a global topological structure of a target graph at the same time.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANN

Artificial neural network

- MILP

Mixed integer linear programming

Appendix A: Statistical features of molecular structures

We observe the following features of the graph-theoretical structure of chemical graphs registered in the chemical database PubChem. Let denote the set of chemical graphs with at most n non-hydrogen atoms that are registered in chemical database PubChem (downloaded a copy on March 21, 2019). The cycle index (or rank) of a chemical graph is defined to be (i.e., the minimum number of edges to be removed to make the graph H acyclic). We call a chemical graph a rank-r chemical graph if the rank of the graph is r. The core of a chemical cyclic graph G is defined to be the induced subgraph of G such that consists of vertices in a cycle or vertices in a path joining two cycles. A vertex in the core (not in the core) is called a core vertex (resp., a non-core vertex). The edges not in the core of a chemical cyclic graph G form a collection of trees T, which we call a non-core tree. Each non-core tree contains exactly one core vertex and is regarded as a tree rooted at the core vertex. The k-branch height of a chemical cyclic graph G is defined to be the maximum of k-branch heights over all non-core trees.

Let (%) denote the ratio of the number of chemical graphs with rank at most to the number of all chemical graphs in PubChem. See Table 11.

Table 11.

The percentage of the number of chemical compounds with rank at most over all chemical compounds in PubChem

Let (%) denote the ratio of the number of chemical graphs in such that the maximum degree is at most to the number of all chemical graphs in . Let (%), denote the ratio of the number of rank-r chemical graphs in such that the maximum degree of a non-core vertex is at most to the number of all rank-r chemical graphs in . See Table 12.

Table 12.

The percentage of the number of chemical compounds with rank such that the maximum degree of a non-core vertex is at most over all rank-r chemical compounds in

Let (%), , , denote the ratio of the number of rank-r chemical graphs in such that the k-branch height is at most h to the number of all rank-r chemical graphs in . See Table 13. We see that most chemical graphs G with at most 50 non-hydrogen atoms satisfy .

Table 13.

The percentage (%) of the number of rank-r chemical graphs in such that the k-branch height is at most h to the number of all rank-r chemical graphs in

We show the distribution of 2-branch height over alkans CH. Let denote the set of all alkans with n carbon atoms, where . Let (%), denote the ratio of the number of alkans in such that the 2-branch height is at most h to the number of alkans in . See Table 14.

Table 14.

The percentage (%) of the number of alkans in such that the 2-branch height is at most h to the number of alkans in

Let denote the ratio of the number of acyclic chemical graphs in such that the degree of the root of the 2-branch-tree is to the number of all acyclic chemical graphs in . See Table 15.

Table 15.

The percentage of the number of acyclic chemical graphs in such that the degree of the root of the 2-branch-tree is to the number of all acyclic chemical graphs in

Among the 2-fringe-trees T of all acyclic chemical graphs in , over of them satisfy for the number of non-hydrogen atoms in a 2-fringe-tree T and the number d of non-hydrogen atoms adjacent to the root in T.

Let denote the set of all 2-fringe-trees that appear in an acyclic chemical graph in , and , denote the set of all 2-fringe-trees that have children (i.e., the degree of the root is ). Let (%) denote the ratio of the number of 2-fringe-trees in that have at most vertices to the number of 2-fringe-trees in . See Table 16.

Table 16.

The percentage (%) of the number of 2-fringe-trees in that have at most vertices to the number of 2-fringe-trees in

Appendix B: Formulating an MILP based on scheme graphs

This section shows how to formulate an MILP based on a scheme graph.

Scheme graphs

Let , , and , be integers such that

;

for , and ; and

.

Let a scheme graph consist of a tree , a path , a set of trees, a set of trees, and a set of directed edges between and so that an acyclic graph will be constructed in the following way:

-

(i)

The -branch-tree of H will be chosen as a subtree of ;

-

(ii)

Each -fringe-tree rooted at a vertex of H will be chosen as a subtree of ;

-

(iii)

Each -branch-path of H (except for its end-vertices) will be chosen as a subpath of or as an edge in ;

-

(iv)

Each -fringe-tree rooted at a vertex of H will be chosen as a subtree of ; and

-

(v)

An edge (u, v) directed from to will be selected as an initial edge of a -branch-path of H and an edge (v, u) directed from to will be selected as an ending edge of a -branch-path of H.

More formally, each component of a scheme graph is defined as follows.

-

(i)

, called a base-tree is a tree rooted at a vertex that is isomorphic to the rooted tree . Regard as an ordered tree by introducing a total order for each set of siblings and call the first (resp., last) child in a set of siblings the leftmost (resp. rightmost) child, which defines the leftmost (rightmost) path from the root to a leaf in , as illustrated in Fig. 4a.

For each vertex , let denote the set of indices i of edges incident to and denote the set of indices i of children of in the tree .

For each integer , let denote the set of indices s of vertices whose depth is d in the tree , where is the set of indices s of leaves of .

Regard each edge as a directed edge from one end-vertex of to the other end-vertex of such that (i.e., is the parent of ), where and denote the head and tail of edge , respectively.

For each index , let (resp., ) denote the set of indices i of edges such that the tail (resp., head) of is vertex .

Let denote the set of indices of leaves of , and (resp., ) denote the index of the leaf at which the leftmost (resp., rightmost) path from the root ends.

For each leaf , , let (resp., ) denote the set of indices s of non-root vertices (resp., indices i of edges ) along the path from the root to the leaf in the tree .

For the example of a base-tree with in Fig. 4, it holds that , , , and .

-

(ii)

, is a tree rooted at vertex in that is isomorphic to the rooted tree , as illustrated in Fig. 4b. Let and denote the vertex and edge in that correspond to the i-th vertex and the i-th edge in , respectively. Regard each edge as a directed edge . For this, each vertex is also denoted by .

-

(iii)

, , , , , , , , called a link-path with size is a directed path from vertex to vertex , as illustrated in Fig. 4a. Each edge is directed from vertex to vertex .

-

(iv)

, is a tree rooted at vertex in that is isomorphic to the rooted tree , as illustrated in Fig. 4c. Let and denote the vertex and edge in that correspond to the i-th vertex and the i-th edge in , respectively. Regard each edge as a directed edge . For this, each vertex is also denoted by .

-

(v)

For every pair (s, t) with and , join vertices and with directed edges and , as illustrated in Fig. 4a.

We explain the basic idea of an MILP in Theorem 2. The MILP mainly consists of the following three types of constraints.

Constraints for selecting an acyclic graph H as a subgraph of the scheme graph

Constraints for assigning chemical elements to vertices and multiplicity to edges to determine a chemical graph ; and

Constraints for computing descriptors from the selected acyclic chemical graph G.

In the constraints of C1, more formally we prepare the following.

-

(i)

In the scheme graph , we prepare a binary variable u(s, 1) for each vertex , so that vertex becomes a -branch of a selected graph H if and only if . The subgraph of the base-tree that consists of vertices with will be the -branch-tree of the graph H. We also prepare a binary variable a(i), for each edge , where . For a pair of a vertex and a child of such that , either the edge is used in the selected graph H (when ) or a path from vertex to vertex is constructed in H with an edge , a subpath of the link-path and an edge (when ). For example, vertices and are connected by a path in the selected graph in Fig. 5c.

-

(ii)Let

-

(iii)

In the link-path , we prepare a binary variable e(t), for each edge so that if and only if edge is used in some path constructed in (i).

-

(iv)

For each pair (s, t) of and , we prepare a binary variable e(s, t) (resp., e(t, s)) so that (resp., ) if and only if directed edge (resp., ) is used as the first edge (resp., last edge) of some path constructed in (i).

Based on these, we include constraints with some more additional variables so that a selected subgraph H is a connected acyclic graph. See constraints (12) to (32) in Appendix C for the details.

In the constraints of C2, we prepare an integer variable for each vertex u in the scheme graph that represents the chemical element if u is in a selected graph H (or otherwise) and an integer variable (resp., ) for each edge e (resp., or e(t, s), , ) in the scheme graph that represents the multiplicity if e is in a selected graph H (or or takes 0 otherwise). This determines a chemical graph . Also we include constraints for a selected chemical graph G to satisfy the valence condition for each edge . See constraints (33) to (47) in Appendix C for the details.

In the constraints of C3, we introduce a variable for each descriptor and constraints with some more variables to compute the value of each descriptor in f(G) for a selected chemical graph G. See constraints (48) to (75) in Appendix C for the details.

Appendix C: All constraints in an MILP formulation for chemical acyclic graphs

To formulate an MILP that represents a chemical graph, we distinguish a tuple from a tuple . For a tuple , let denote the tuple . Let . We call a tuple proper if and , where the latter is assumed because otherwise G must consist of two atoms of . Assume that each tuple is proper. Let be a fictitious chemical element that represents null, call a tuple with fictitious, and define to be the set of all fictitious tuples; i.e., . To represent chemical elements in an MILP, we encode these elements into some integers denoted by . Assume that, for each element , is a positive integer and that .

Upper and lower bounds on descriptors

In our formulation of an MILP for inferring a vector in Stage 4, we fix the following descriptors as specified constants: the number n(G) of vertices, the diameter , and the number of leaf -leaf branches, which are set to be given integers , , and , respectively. For each of the other descriptors, we specify a lower bound and an upper bound on the value so that the descriptor takes a value from the range between and .

constants

: the size n(G) of G;

: lower and upper bounds on the number of -internal/-external vertices of degree i in G;

, : lower and upper bounds on the number of -internal/-external vertices v with in G;

, : lower and upper bounds on the number of -internal/-external edges e with in G;

: lower and upper bounds on the number of -internal/-external edges e with adjacency-configuration in G;

, : lower and upper bounds on the number of -internal/-external edges e with bond-configuration in G;

variablesxfor descriptors

, : (resp., ) represents (resp., );

, : (resp., ) represents (resp., );

, : (resp., ) represents (resp., );

, : (resp., ) represents (resp., );

, : (resp., ) represents (resp., );

constraints

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

We use the range-based method to define an applicability domain for our method. For this, we find the range (the minimum and maximum) of each descriptor over all relevant chemical compounds and represent each range as a set of linear constraints in the constraint set of our MILP formulation. Recall that stands for a set of chemical graphs used for constructing a prediction function. However, the number of examples in may not be large enough to capture a general feature on the structure of chemical graphs. For this, we also use some data set from the whole set of chemical graphs in a database. Let denote the set of chemical graphs such that for each integer . Based on this, we assume that the given lower and upper bounds on the above descriptors satisfy the following. For each ,

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Construction of scheme graph

We infer a subgraph H such that the maximum degree is , , , and . For this, we first construct the scheme graph . We then prepare a binary variable u(s, i) (resp., v(t, i)) for each vertex in tree (resp., in tree ).

Recall that when the two end-vertices of edge is connected in a selected subgraph H, either edge is directly used in H or a path from to visiting some vertices in is constructed in H. We regard the index i of each edge as the “color” of the edge, and define the color set of to be . To introduce necessary linear constraints that can construct such a path properly in our MILP, we assign the color i to the vertices in when a path is used in H.

constants

Integers , , , , and ;

variables

, : a(i) represents edge (, ) ( edge is used in H);

, , : e(s, t) (resp., e(t, s)) represents direction (resp., ), where (resp., ) edge is used in H and direction (resp., ) is assigned to edge ;

, : represents the color assigned to vertex ( vertex is assigned color c, where iff is not in H);

, , ( );

, : the number of vertices with color c;

, : the out-degree of vertex in the -branch-subtree of H;

, : the in-degree of vertex in the -branch-subtree of H;

constraints

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

Selecting a subgraph

From the scheme graph , we select a subgraph H such that , , , and .

constants

Integers , , , , and ;

- For each tree , prepare

- the set of the indices of children of a vertex ;

- the index of the parent of a non-root vertex ;

- the set of indices i of a vertex whose depth is d;

- a proper set of index pairs,

- where we denote by ;

- For each tree , prepare

- the set of the indices of children of a vertex ;

- the index of the parent of a non-root vertex ;

- a proper set of index pairs,

- where we denote by ;

variables

, : ( vertex is a non-leaf -branch or a root);

, , : u(s, i) represents vertex ( vertex is used in H and edge is used in H), ( and vertex is a leaf -branch);

, , : v(t, i) represents vertex ( vertex is used in H and edge is used in H);

, : e(t) represents edge , where and are fictitious edges ( edge is used in H);

constraints

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

| 23 |

| 24 |

| 25 |

| 26 |

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

| 30 |

| 31 |

| 32 |

Constraints (21) and (22) represent an extension of constraint (1) on the size of 2-fringe-trees to the case of a general branch-parameter .

Assigning multiplicity

We prepare an integer variable or for each edge e in the scheme graph to denote the multiplicity of e in a selected graph H and include necessary constraints for the variables to satisfy in H.

constants

Prepare functions and such that ;

Assume that each edge in a tree , (resp., , ) is denoted by (resp., ) with the integer of the head (resp., ) of the edge;

variables

, : represents the multiplicity of edge , where if edge is not in an inferred chemical graph G;

, , : with (resp., ) represents the multiplicity of edge (resp., );

, : represents the multiplicity of edge ;

, , : represents the multiplicity of edge ;

constraints

| 33 |

| 34 |

| 35 |

| 36 |

| 37 |

Assigning chemical elements and valence condition

We include constraints so that each vertex v in a selected graph H satisfies the valence condition; i.e., . With these constraints, a chemical acyclic graph on a selected subgraph H will be constructed.

constants

A set of chemical elements, where denotes null;

A coding , such that ; , ; and if ; Let and denote and , respectively;

A valence function: ;

Let denote the set of indices i of all edges adjacent to vertex in .

variables

, , : with (resp., ) represents (resp., );

, , , : for and for ;

, , , : the multiplicity of edge in an inferred chemical graph G is m;

, , , : the multiplicity of edge , (or , ) in G is m;

, , : the multiplicity of edge in G is q;

, , , : the multiplicity of edge in G is m;

constraints

| 38 |

| 39 |

| 40 |

| 41 |

| 42 |

| 43 |

| 44 |

| 45 |

| 46 |

| 47 |

Descriptors on mass, the numbers of elements and bonds

We include constraints to compute descriptors , (, () and according to the definitions in "Modeling of chemical compounds" section.

constants

A function (we let denote the observed mass of a chemical element , and define );

variables

: represents ;

, ;

: the number of hydrogen atoms to be included to G;

constraints

| 48 |

| 49 |

| 50 |

| 51 |

Descriptor for the Number of Specified Degree

We include constraints to compute descriptors () according to the definitions in "Modeling of chemical compounds" section. We also add constraints so that the maximum degree of a vertex in H is at most 3 (resp., equal to 4) when (resp., .

variables

, , : represents for or for ;

, , , : ;

constraints

| 52 |

| 53 |

| 54 |

| 55 |

| 56 |

| 57 |

| 58 |

Descriptor for the number of adjacency-configurations

We include constraints to compute descriptors () according to the definitions in "Modeling of chemical compounds" section.

constants

A set of proper tuples ;

The set ;

variables

, , : edge is assigned tuple ; i.e., ;

, , : edge is assigned tuple ; i.e., ;

, , , : edge , (or , ) is assigned tuple ; i.e., ;

, , , : edge is assigned tuple ; i.e., ;

constraints

| 59 |

| 60 |

| 61 |

| 62 |

| 63 |

| 64 |

| 65 |

| 66 |

Descriptor for bond-configuration

We include constraints to compute the descriptors for bond-configuration , , according to the definition.

variables

, ;

, , , : , and in G;

, , , : , and in G;

, , , , : , and for (or , and for ) in G;

, , , , : , and in G;

constraints

| 67 |

| 68 |

| 69 |

| 70 |

| 71 |

| 72 |

| 73 |

| 74 |

| 75 |

Appendix D: Descriptions of new graph search algorithms

Multi-rooted trees and frequency vectors

For a finite set A of elements, let denote the set of functions . A function is called a non-negative integer vector (or a vector) on A and the value for an element is called the entry of for . For a vector and an element , let (resp., ) denote the vector such that (resp., ) and for the other elements . For a vector and a subset , let denote the projection of to B; i.e., such that , .

Let denote the set of tuples (bond-configuration) such that . For two tuples , we write if

, and ,

and write if

and .

Let , where denotes the number of vertices with degree i.

Henceforth we deal with vectors that have their and components, both , and for convenience we write in the sense of concatenation.

For a vector with , let denote the set of chemical acyclic graphs G whose 2-internal (resp., 2-external) vertices/edges are determined by the vector (resp., ); i.e., G satisfies the following:

and for each chemical element ,

and for each adjacency-configuration ,

and for each bond-configuration ,

and for each degree .

Throughout the section, let be a branch-parameter, be a given feature vector with , and be an integer. We infer a chemical acyclic graph such that and the diameter of G is , where . Note that any other descriptors of can be determined by the entries of vector .

To infer a chemical acyclic graph , we consider a connected subgraph T of G that consists of

| 76 |

Our method first generates a set of all possible rooted trees T that can be a 2-fringe-tree of a chemical graph , and then extends the trees T by repeatedly appending a tree in until a chemical graph is formed. In the extension, we actually manipulate the “frequency vectors” of trees defined below.

To specify which part of a given tree T plays the role of 2-internal vertices/edges or 2-external vertices/edges in a chemical graph to be inferred, we designate at most three vertices , , and , in T as terminals, and call T rooted (resp., bi-rooted and tri-rooted) if the number of terminals is one (resp., two and three). For a rooted tree (resp., bi- or tri-rooted tree) T, let denote the set of vertices contained in a path between two terminals of T, denote the set of edges in T between two vertices in , and define and . For a bi- or tri-rooted tree T, define the backbone path of T to be the path of T between vertices and .

Given a chemical acyclic graph T, define , , to be the vector that consists of the following entries:

, ,

, ,

, ,

, .

Define . The entry for an element in , is denoted by . For a subset B of , let denote the projection of onto B.

Our aim is to generate all chemical bi-rooted (resp., tri-rooted) trees T with diameter such that .

A new algorithm for computing chemical bi-rooted trees G with

This section describes a sketch of our new graph search algorithm for the case of . See Appendix “A sketch of algorithm for computing chemical tri-rooted trees G with ” for a sketch of a new algorithm for the case of .

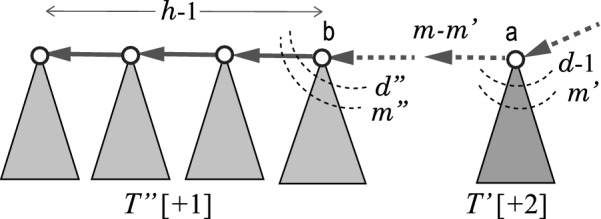

We call a chemical graph with diameter and a target graph.

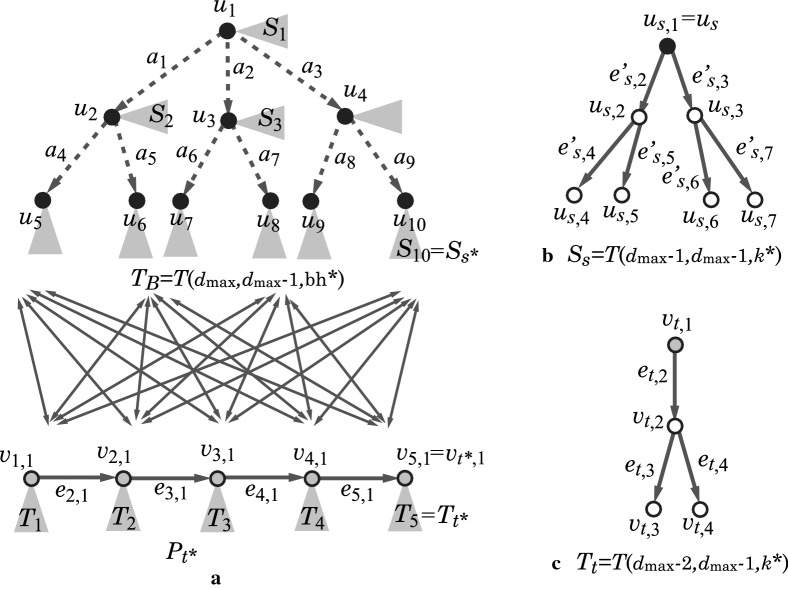

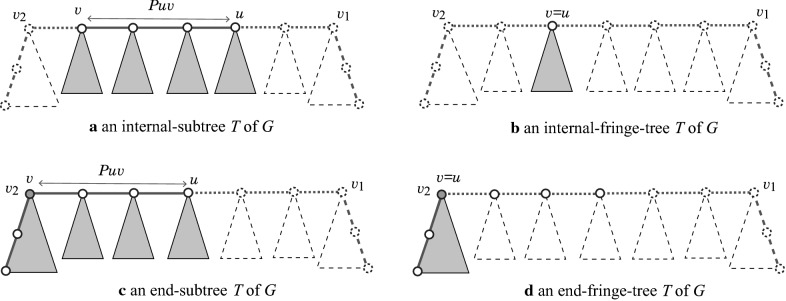

A chemical acyclic graph G with has exactly two leaf 2-branches , , where the length of the path between the two leaf 2-branches and of a target graph G is . We observe that a connected subgraph T of a target graph G that satisfies (76) for is a chemical rooted or bi-rooted tree with roots u and v, where possibly . We call such a subgraph T an internal-subtree (resp., end-subtree) of G if neither (resp., one) of u and v is a 2-branch in G. When , we call an internal-subtree (resp., end-subtree) T of G an internal-fringe-tree (resp., end-fringe-tree) of G. Figure 10a–d illustrates an internal-subtree, an internal-fringe-tree, an end-subtree and an end-fringe-tree of G.

Fig. 10.

An illustration of subtrees T of a chemical acyclic graph G in Fig. 6a, where the vertices/edges in T are depicted by solid lines: a An internal-subtree T of G; b An internal-fringe-tree T of G; c An end-subtree T of G; d An end-fringe-tree T of G

Let and . We regard a target graph with and diameter as a combination of two chemical bi-rooted trees and with , , joined by an edge , as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

An illustration of combining two bi-rooted trees and with a new edge with multiplicity m joining vertices and to construct a target graph G, where , , , , and

We start with generating chemical rooted trees and then iteratively extend chemical bi-rooted trees T with , before we finally combine two chemical bi-rooted trees and with . To describe our algorithm, we introduce some notation.

Let denote the set of all bi-rooted trees T (where possibly ) such that and , which is a necessary condition for T to be an internal-subtree or end-subtree of a target graph .

Let denote the set of all rooted trees that can be a 2-fringe-tree of a target graph G, where T satisfies the size constraint (1) of 2-fringe-trees.

For each integer , let denote the set of all bi-rooted trees that can be an end-subtree of a target graph G such that , and each 2-fringe-tree rooted at a vertex v in belongs to .

The idea of our new algorithm is to compute only the set of frequency vectors of end trees, whose size is much more restricted than that of . We compute the set of frequency vectors of trees in iteratively for each integer . During the computation, we keep a sample of a tree for each frequency vector so that a final step can construct some number of target graphs G by assembling these sample trees. Based on this, we generate target graphs by the following steps:

-

(i)Compute by a branch-and-bound procedure that generates all possible rooted trees (where ) that can be a 2-fringe-tree of a target graph ;

-

(ii)Compute the set of all vectors such that and for some tree , and let be those trees with height exactly 2;

-

(iii)For each vector , choose a sample tree such that and , and store these sample trees;

-

(i)

- For each integer , iteratively execute the next:

-

(i)Compute the set of all vectors such that and for some bi-rooted tree , where such a vector is obtained from a combination of vectors and ;

-

(ii)For each vector , store a sample tree , which is obtained from a combination of sample trees with and with ;

-

(i)

We call a pair of vectors and feasible, if it admits a target graph such that and . Find the set of all feasible pairs of vectors and ;

For each feasible vector pair , construct a corresponding target graph G by combining the corresponding samples trees and , as illustrated in Fig. 11.

Detailed descriptions of the five steps in the above algorithm can be found in Appendix “Case of two leaf 2-branches”.

For a relatively large instance with and , the number of feasible vector pairs in Step 4 is still very large. In fact, the size of a vector set to be computed in Step 2 can also be considerably large during an execution of the algorithm. For such a case, we impose a time limitation on the running time for computing and a memory limitation on the number of vectors stored in a vector set . With these limitations, we can compute only a limited subset of each vector set in Step 2. Even with such a subset , we still can find a large size of a subset of in Step 3.