Contribution summary statement:

The majority of parents accept STI screening for their adolescent at a pediatric office visit. Parents believe it is important their adolescent spend time alone with their provider, and think it is important for providers to discuss sexual health topics.

Introduction

Approximately half of chlamydia and gonorrhea cases in the United States occur in 15–24 year olds [1]. Routine chlamydia and gonorrhea screening is recommended for sexually active females less than 25 years old and for young men who have sex with men [2]. Despite these recommendations, fewer than 1 in 3 sexually active female adolescents report receiving STI counseling, screening, or treatment in the previous year [3].

Pediatricians have opportunities to provide sexual health counseling and STI screening to adolescents, yet chlamydia screening is performed less often by pediatricians than providers in other specialties [4]. In a network of pediatric practices, only one-third of female sexually-active adolescents were screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea at well visits [5]. Lack of parental support, confidentiality, and awkwardness asking parents for privacy are some barriers to screening [6, 7].

Less than half of adolescents report spending time alone with their pediatrician during preventive visits [8]. Sexual health topics are not discussed as often as other preventive topics (e.g., substance use) [9]. Even though adolescents in many states can consent to STI testing, pediatricians might be more willing to offer sexual health services if they knew parents would agree. However, few studies have determined parental views about sexual health care [10]. We explored whether parents would accept chlamydia and gonorrhea screening for their adolescent during a pediatric visit, and assessed parental views on the importance of sexual health services.

Methods

An anonymous survey was administered to parents accompanying their child to appointments at pediatric practices from June 2017-July 2018. Two practices were urban [Pittsburgh PA], and one was in a mostly rural county [Armstrong County, PA]. A convenience sample was based on the lead investigator’s (KL) availability. Eligible parents had at least one female or male adolescent aged 15–17 years. Parents were approached in the waiting room and verbally consented to self-administer a web-based survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). If parents were accompanying a younger (<15) or older (>17) adolescent, they answered with their oldest 15–17 year old in mind. The questions were piloted with 10 parents for comprehensibility. This study was approved by The University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board.

The primary outcome was parental acceptance of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening for their adolescent. A short introduction explained that chlamydia and gonorrhea are common among adolescents, are often asymptomatic, and may lead to long term problems, e.g. infertility. In addition to parent and child demographics, parents were asked if they would allow their adolescent to be screened for chlamydia and gonorrhea (urine) if offered at this visit. Known or suspected sexual activity was not a requirement. Responses were categorized as yes if parents would accept screening, and no if parents responded no or unsure.

Parents were categorized as recognizing the importance of providers spending time alone with their adolescent if they responded that it was “important” or “very important” on a four-point Likert scale (not important, somewhat important, important or very important). Parents also rated the importance of 6 sexual health and 6 preventive health topics on the same four-point scale. The sexual health topics included STIs, HIV/AIDS, safe sex practices, STI screening, pregnancy prevention, and contraception [7]. The preventive health topics were among those most frequently rated by parents as important to discuss during well visits [10]. The topics were randomly sorted for each participant by the survey tool. Variables were assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test to identify factors associated with parental acceptance of screening.

Results

Of the 196 parents approached, 168 (86%) agreed to participate. Parents were mostly female (87%) and 77% were married (Table 1). The mean age was 46 years (range 32–64). Most (87%) parents were accompanying a 15–17 year old to an appointment. Parents identified as White (85%), African American (12%), and Asian (3%). Participants reflected the population served by the practices.

Table 1.

Parent factors and acceptance of STI screening

| Variable | N | % | Accepted screeninga n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender Identity of Parent | ||||

| Female | 146 | 87% | 93 (64%) | 0.22 |

| Male | 22 | 13% | 11 (50%) | |

| Raceb | ||||

| Black | 21 | 12% | 19 (90%) | <0.01 |

| White/Other | 149 | 88% | 87 (58%) | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤45 | 78 | 48% | 48 (62%) | 0.99 |

| >45 | 83 | 52% | 51 (61%) | |

| Education Level | ||||

| High School | 33 | 20% | 22 (67%) | 0.53 |

| > High School | 135 | 80% | 82 (61%) | |

| Gender Identity of Adolescent | ||||

| Female | 80 | 48% | 50 (63%) | 0.87 |

| Male | 88 | 52% | 55 (63%) | |

| Reason for Appointment | ||||

| Sick | 61 | 36% | 41 (67%) | 0.62 |

| Routine | 86 | 51% | 51 (59%) | |

| Sibling | 21 | 13% | 13 (62%) | |

| Has an Adult Child (Aged ≥18 Years) | ||||

| Yes | 71 | 42% | 45 (63%) | 0.84 |

| No | 97 | 58% | 60 (62%) | |

| Believes it is Important Adolescent Spends Time Alone with Provider | ||||

| Yes | 123 | 73% | 83 (67%) | <0.01 |

| No | 45 | 27% | 21 (47%) | |

| Aware of Adolescent’s Sexual Activity | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 16% | 22 (81%) | <0.05 |

| No | 141 | 84% | 82 (58%) | |

Total number of responses = 168, and p < 0.05 is considered significant.

Row percent

Parents could identify as more than one race

Sixty three percent (105/168) of parents would accept chlamydia and gonorrhea screening for their adolescent if offered by their pediatric provider. Among parents who were unsure (n = 39, 23%) or would decline (n = 24, 14%), 47 (75%) did not think their adolescent was sexually active. Parents aware their adolescent was sexually active were significantly more likely to accept screening (81% vs 58%, p<0.05). While 90% (19/21) of Black parents accepted screening, so did the majority (58%) of non-Black parents. There was no significant difference in acceptance of screening between rural and urban practices (61% vs 65%, p=0.57).

Seventy three percent (123/168) of parents responded it is very important (n = 54, 32%) or important (n = 69, 41%) their adolescent spend time alone with their provider, with 7% stating it was not important. Parents favoring providers spending time alone were more likely to accept STI screening than parents responding it was somewhat or not important (67% vs 47%, p<0.01).

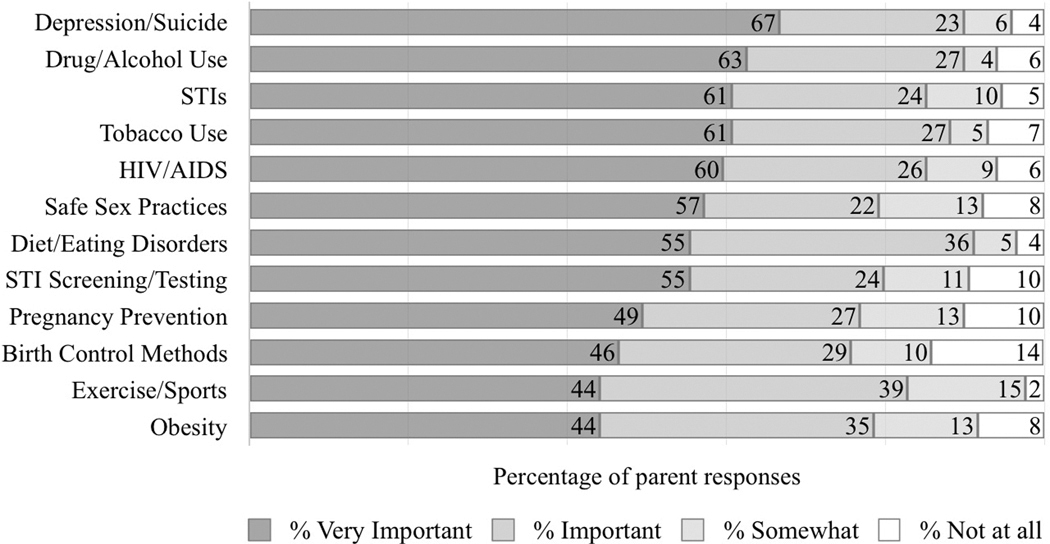

STI/HIV counseling, safe sexual practices, and STI screening were viewed as important by the majority of parents and were ranked as high as other preventive topics (Figure 1). Parents responded STI prevention discussions should start between 13–15 years (39%) or 15–17 years (37%). Another 21% said before age 13, while 3% said once they reach age 18. Only one parent felt providers should not discuss STIs.

Figure 1.

Importance of pediatric provider discussing prevention health topics

Parents rated the importance providers discussing 12 health topics. Figure values represent the percentage of parents that selected each of the four-point Likert-like scale responses. Total number of responses = 168.

Discussion

Most parents are accepting of chlamydia and gonorrhea screening for their adolescent during pediatric office visits. There was no difference in acceptance of STI screening based on parent gender, age, education level, or gender identity of their adolescent. Acceptance was common regardless of parental race or parent knowledge of adolescent sexually activity. Our results are consistent with research showing that parents feel it is important for adolescents to spend time alone with their pediatric provider [11]. Further, our study demonstrates that parents rank delivery of STI and sexual health care as high as other preventive health services.

While we recruited from both rural and urban practices, our population was predominately white and the majority had greater than high-school education, which may influence generalizability of results to more diverse clinical settings. We observed higher acceptance of STI screening among parents who identified as Black; however, the sample was small, limiting our ability to identify differences. Studies are needed to understand low acceptance of screening among some parents and why parents rate particular health topics as less important.

Our study did not address the many other barriers to STI screening in pediatrician offices, such as provider knowledge and comfort with sexual health, confidentiality concerns, and time constraints. However, our study suggests most parents will accept STI screening for their adolescent. Pediatricians should use this information to facilitate STI screening during office visits, see their patients, and offer sexual health counseling.

Acknowledgments:

This study was supported by an NIH grant, UL1TR001857. Only the named authors made substantive contributions to this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the Authors. Poster presentations: 2018 Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Toronto, Canada, 2018 STD Prevention Conference in Washington, DC, USA.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: Prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40(3):187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Haderxhanaj LT, Gift TL, Loosier PS, et al. Trends in receipt of sexually transmitted disease services among women 15 to 44 years old in the United States, 2002 to 2006–2010. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41(1):67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hoover KW, Leichliter JS, Torrone E, et al. Chlamydia screening among females aged 15–21 years — multiple data sources, United States, 1999–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63(Suppl 2):80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goyal MK, Witt R, Hayes KL, et al. Clinician adherence to recommendations for screening of adolescents for sexual activity and sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr 2014;165(2):343–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cook RL, Wiesenfeld HC, Ashton MR, et al. Barriers to screening sexually active adolescent women for chlamydia: a survey of primary care physicians. J Adolesc Health 2001;28(3):204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Miller KS, Wyckoff SC, Lin CY, et al. Pediatricians’ role and practices regarding provision of guidance about sexual risk reduction to parents. J Prim Prev 2008;29(3):279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Adams SH, Husting S, Zahnd E, Ozer EM. Adolescent preventive services: rates and disparities in preventive health topics covered during routine medical care in a California sample. J Adolesc Health 2009;44(6):536–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Henry-Reid LM, O’Connor KG, Klein JD, et al. Current pediatrician practices in identifying high-risk behaviors of adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dempsey AF, Singer DD, Clark SJ, Davis MM. Adolescent preventive health care: What do parents want? J Pediatr 2009;155(5):689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miller VA, Friedrich E, Garcia-Espana JF, et al. Adolescents spending time alone with pediatricians during routine visits: perspectives of parents in a primary care clinic. J Adolesc Health 2018;63(3):280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]