Abstract

Poly(ADP-ribosyl) polymerase-1(PARP-1) is an abundant ADP-ribosyl transferase that regulates various biological processes. PARP-1 is widely recognized as a first-line responder molecule in DNA damage response (DDR). Here, we review the full cycle of detecting the DNA damage by PARP-1, PARP-1 activation upon DNA binding, and PARP-1 release from DNA break. We also discuss the allosteric consequence upon binding of PARP inhibitors (PARPi) and the opportunity to tune its release from a DNA break. It is now possible to harness this new understanding to design novel PARPi for treating diseases where cell toxicity caused by PARP-1 “trapping” on DNA is either the desired consequence or entirely counterproductive.

Keywords: DNA damage response, PARylation, Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase, PARPi

PARP-1 is the major DNA damage ADP-ribosyltransferase

ADP-ribosylation is a highly conserved and reversible post-translational modification (see Glossary) that involves the addition of ADP-ribose (ADPr) residues from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to substrates. ADP-ribosylation regulates various cellular processes, such as DNA repair, transcription, telomere lengthening, and apoptosis [1]. Poly(ADP-ribosyl) transferases (PARPs) are one of the most-studied ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) enzymes that catalyze ADP-ribosylation. The human PARP family includes eighteen putative PARP homologues encoded by different genes [2]. Among human PARPs, PARP-1, PARP-2, and PARP-3 are classified as DNA damage response (DDR) PARPs because of their involvement in DNA damage repair [3–5]. PARP-1 and PARP-2 can uniquely catalyze the formation of long and branched poly-ADPr polymers (PARylation), whereas PARP-3 catalyzes mono ADP-ribosylation (MARylation) [6]. Aside from these three DDR PARPs, other PARPs play roles in other cellular processes [1, 2].

PARP-1 is the major DDR PARP in terms of abundance and enzymatic output in response to DNA damage [7]. The rapid activation of PARP-1 is the foremost step in the DDR process. Genomic instability caused by defects in the DDR process is a key hallmark of cancer that immediately made PARP-1 an attractive candidate to target. Various small molecule PARP inhibitors (PARPi) that target the PARP-1 catalytic activity in DDR are now approved and in the clinic for breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer patients [8–9] with defects in other DDR components (e.g. those carrying BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations) and under consideration for expanded utilities in other patients/cancer types [10–12].

This review covers recent advances in understanding the full cycle PARP-1 takes starting with DNA break recognition, then its activation upon binding to broken DNA, and finally its release from the DNA break after signaling. These steps are modulated intrinsically (i.e. via allosteric regulation and automodification) [13–15] and extrinsically (i.e. via binding accessory factors and PAR hydrolyzing enzymes) [16–18], providing an expanding spectrum of possible modes of targeting PARP-1 in cancer using PARPi, as well as for proposed utility in treating cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammation.

PARP-1 in DNA damage repair

The first-line sensor of DNA damage

The rapid detection of DNA damage (i.e. within 1–3 seconds of its formation) by PARP-1 and its ADP-ribosylation of many different proteins near the damage site initiates recruitment of repair complexes [12]. Mammalian PARP-1 is a multifaceted enzyme comprised of six distinct domains (Figure 1A). Prior to binding to a DNA break, PARP-1 represents a “beads on a string” like architecture [19] and possesses low basal activity. PARP-1 activity is stimulated by 1000-fold when it engages DNA breaks [20]. Indeed, PARP-1 is considered the primary responder to single strand breaks (SSBs) [12, 21], the most common form of DNA damage. PARP-1, however, is capable of binding and signaling other forms of DNA damage, including double strand breaks (DSBs) [15].

Figure 1. Structure of PARP-1 on a DNA break and relationship to other DNA damage PARPs.

(A) Domains of human PARP-1. The N-terminal domain includes zinc-fingers (F1, F2, and F3), followed by automodification domain (AD) which has automodification sites. The DNA binding (WGR) domain and catalytic (CAT) domain resides at C-terminal domain. The helical domain (HD) and ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) domain comprise the CAT domain. (B) Combined model of the crystal structure of F1, F3, and WGR-CAT with DNA complex (PDB:4DQY) and NMR structure of F1-F2 with an SSB [25]. (C) Domain organization of the three DNA damage PARPs. The N-terminal region (NTR) of PARP-1 has three zinc-fingers (F1, F2, and F3) and BRCT domain whereas PARP-2 and PARP-3 has shorter NTR and lack zinc-fingers. All three DNA damage PARPs share WGR, HD, and ART domain. (D) Similarities and differences in the biochemical activities of the three DNA damage PARPs. BER: base excision repair, SSBR: single strand break repair, DBSR: double strand break repair, HR: homologous recombination and NHEJ: non-homologous end joining.

Various studies have provided key insights on how PARP-1 detects DNA damage and becomes activated. For instance, the two homologous zinc-finger F1 and F2 domains of PARP-1 recognize a specialized DNA structure rather than a specific DNA sequence. The crystal structure of F1 and F2 bound to a DSB suggests that these domains interact with exposed nucleotide bases using a “base-stacking loop” that connects two β strands [22]. Additionally, the continuous phosphate backbone of DNA interacts with a second region, termed the “backbone grip”, found in the F1 domain [22]. F1 is a central player for PARP-1 activation, whereas the precise role of F2 in PARP-1 activation is still unclear, though F2 has been proposed to be important for the recognition of SSBs but not for DSBs [23]. Structural studies show F1 and F2 interact similarly with DNA [22]; nonetheless, biochemical studies have shown different DNA affinities for F1 and F2 [22]. Indeed, these studies showed F1 has significantly lower DNA affinity than F2 but is essential for DNA damage-dependent activation of PARP-1, whereas F2 is dispensable for PARP-1 activation [22]. High binding affinity for DNA suggest that F2 is important for PARP-1 localization and retention to DNA break [24]. The zinc finger F3 domain is also important for PARP-1 activation because it contains key residues that mediate interdomain contacts and are essential for PARP-1 assembly upon DNA damage-dependent activation [20]. F3 has a structure unrelated to that of F1 and F2 and does not directly bind to DNA [20]. Rather, recognition of the DNA break by F1 and F2 directs the interaction of F3 with F1 and DNA [25].

DNA damage detection by PARP-1 zinc finger domains is critical for PARP-1 activation resulting in a collapsed PARP-1 structure where the zinc fingers F1 and F3, WGR domain, and the catalytic (CAT) domain collectively bind to damaged DNA and creates a network of interdomain contacts [20,26,27] (Figure 1B). The WGR domain is a DNA binding domain and participates in DNA damage-dependent activation. The CAT domain comprises two subdomains: a helical domain (HD) and an ADP-ribosyltransferase (ART) domain. Further, interdomain contacts in the collapsed PARP-1 structure result in destabilization of HD and allosteric activation of enzyme [13] (discussed below). PARP-1 shares conserved C-terminal domains (WGR and CAT domain) with other DDR PARPs PARP-2 and PARP-3. The major structural difference among PARP-1, PARP-2, and PARP-3 occurs at N-terminal region (NTR) (Figure 1C). The NTR of PARP-1 is longer (≥500 residues) than PARP-2 and PARP-3 (70 and 40 residues, respectively) [28]. Unlike that of PARP-1, the NTRs of PARP-2 and PARP-3 are less important for DNA binding affinity and not absolutely required for enzyme activation [28]. The NTR of PARP-2 possess nucleolar localization sequence and a nuclear localization signal [29]. The DNA damage-dependent activation of PARP-2 occurs through similar allosteric mechanism as PARP-1 [13, 28]. The WGR domain of PARP-2 binds to 5’-phosphorylated site, inducing conformational changes in regulatory HD domain, and releasing the enzyme from its autoinhibition state [30]. PARP-2 interacts with SSB repair factors XRCC1, DNA polymerase β, and DNA ligase III similarly to PARP-1 [31]. Further, the recruitment of PARP-2 to DNA lesion is PARP-1 PARylation-dependent [32], potentially suggesting a stepwise recruitment of PARP-1, then PARP-2. Additionally, the combined loss of both isoforms results in impaired base excision repair with upregulated replication associated DNA damage [33]. Genetic evidence also emphasizes the functional importance of both DDR proteins; PARP1−/− or PARP2−/− mice have subtle defects in DDR whereas PARP1−/− and PARP2−/− double mutant mice die at the onset of gastrulation indicating redundancy of essential function in the early embryo [34]. Further, PARP-1, PARP-2, and PARP-3 have distinct biochemical properties, recognizing different DNA lesions for signaling to different DNA repair pathways (Figure 1D).

Allosteric switch in PARP-1 confers PARP-1 activation

PARP-1 binding to broken DNA results in a network of interdomain contacts that lead to the loss of stable structure in three of the seven helices that comprise the HD [13]. The structural ‘snapshot’ provided by a crystal structure of PARP-1 bound to a DNA break showed some distortion in the HD [26]. In addition, measuring the dynamics of the polypeptide backbone of PARP-1 by hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry (HXMS) revealed that binding of PARP-1 to a DNA break causes local unfolding within the HD [13]. Together, these findings indicate that destabilization of the HD activates PARP-1 by relieving enzymatic autoinhibition. Indeed, in the absence of DNA damage, the folded HD blocks the access of NAD+ to the active site, keeping PARP-1 at its minimal basal activity [14]. Binding to DNA damage leads to local unfolding in the HD and allows the full access of NAD+ to the catalytic active site, leading to massive activation of PARP-1 activity [14] (Figure 2). NMR experiments have further indicated that interaction of PARP-1 with a SSB, followed by NAD+ binding, results in stepwise and additive destabilization of the HD, during activation [35]. Altogether, these studies describe the allosteric mechanism by which binding to a DNA break at one surface of the PARP-1 enzyme activates catalysis that occurs ~40 Å away.

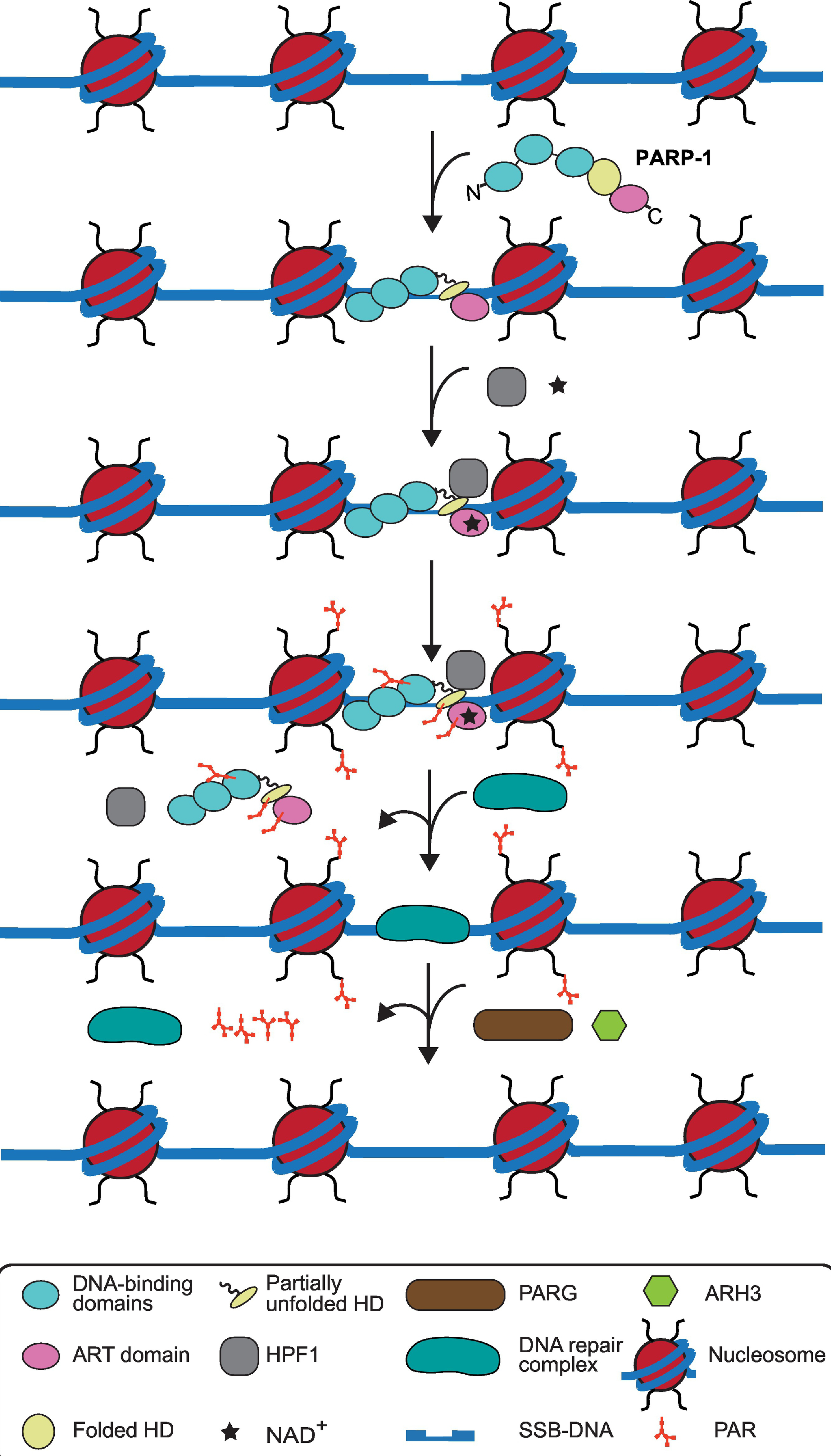

Figure 2. Simplified cycle of PARP-1 on and off of a DNA break.

In the absence of DNA damage, PARP-1 domains are unconnected, resembling a beads-on-a-string arrangement. The helical domain (HD) is an autoinhibitory domain and regulates PARP-1 catalytic activity via blocking the NAD+ binding to the nicotinamide site (N) of the ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) domain. PARP-1 detects DNA damage through its DNA binding domains (zinc fingers F1, F2, and F3) and collapses into a compact conformation around the broken DNA lesion. The resulting interdomain contacts destabilize the HD (double headed arrow), permitting NAD+ ready access to N. NAD+ binding reciprocally strengthens the PARP-1 interaction with broken DNA through reverse allosteric communication from catalytic domain to DNA binding domains (single-headed arrow). PARP-1 automodification, predominantly at the BRCT automodification domain (AD) permits PARP-1 release from DNA.

PARP-1 function is regulated by accessory factors at DNA breaks

The cellular function of PARP-1 is coordinated by a network of other signaling factors in DDR. The heterodimer Ku (Ku70/Ku80), a signaling factor involved in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) [36], competes with PARP-1 to recognize and bind to DSB and is recruited to damage site in a cell-cycle dependent manner [37]. The Ku complex is primarily recruited to DNA break in G1/S whereas PARP-1 occupies damage site in S/G2 phase [37]. PARP-1 is also known to regulate the recruitment of DSB sensor proteins Mre11 and Nbs1 to DNA lesions [24]. Additionally, PARP-1 activity is repressed by TRF2 to protect telomeres to prevent DDR for telomeric DNA ends [38].

A fascinating example of a PARP-1 accessory factor is Histone PARylation Factor 1 (HPF1) that modulates PARP-1 catalytic activity in a manner that increases catalysis and switches substrate specificity [16]. HPF1 binds the PARP-1 catalytic domain and co-localizes with PARP-1 to damage sites [16] (Figure 3). Two conserved residues, Tyr238 and Arg239, of HPF1 identified in the acidic corner of its C-terminal domain are important for PARP-1-HPF-1 interaction [16]. Recent structural analysis with PARP-2, the closest relative to PARP-1, indicated that Arg239, Asp283, Asp286, and Glu284 are the key residues in HPF-1 for binding the catalytic domain of PARP-2 [39]. Moreover, functional studies have also confirmed that mutation of Arg239, Asp283, or Asp286 drastically reduces the catalytic activity of PARP-1 [39]. Further, the E284A mutant nearly eliminates PARP-1 ADP-ribosylation [39]. The PARP-1-HPF1 interaction limits PARP-1 hyper-automodification and promotes trans ADP-ribosylation of histones [16] and proteins involved in downstream steps in DNA repair [40]. HPF1 also modulates the activity of the closest relative of PARP-1, PARP-2 [16]. The cryo-EM structure of PARP-2 and HPF1 bridging two nucleosomes with the broken DNA showed that bridging a DSB induces structural changes in the HD of PARP-2 that permits HPF1 binding and result in PARP-2 activation [41]. Thus, in addition to relieving autoinhibition [13], HD unfolding permits the HPF-1-mediated serine-directed ADP-ribosylation activity of PARP-2.

Figure 3. The cycle of PARP-1 in DDR signaling in the context of chromatin, HPF1, downstream repair factors, and PAR hydrolyzing enzymes.

PARP-1 detects and binds to damaged DNA with allosteric changes in helical domain (HD) domain. HPF1, an accessory factor, binding to the catalytic domain and NAD+ access results in catalytic activation of PARP-1. PARP-1 and HPF1 are thought to form a composite active site for PARylation of PARP-1 and histones present in nucleosomes in the vicinity of DNA break. PARP-1 automodification leads to its release from DNA. The removal of PARP-1 and PAR residues on histones occurs simultaneously with the recruitment of DNA repair complex, consisting of XRCC1, APTX, PNKP, DNA Polymeraseβ, and Ligase 3α. Lastly, after the DNA break is repaired, then the repair complex is dissociated from DNA and PARG and ARH3 remove local PAR chains.

Perhaps the most intriguing activity of HPF1 is that it switches PARP-1 substrate specificity from modifying Asp/Glu residues to Ser residues [16, 39, 40, 42]. A recent crystal structure at 2.1 Å resolution has provided molecular details of the HPF1-PARP-2 interaction and insight into how the related HPF1-PARP-1 interaction likely occurs [39]. Co-crystallization of HPF1 (Δ1–36) and PARP-1/2 CATΔ HD suggests that HPF1 and PARP-2 form a joint active site [39]. The joint active site is stabilized by an interaction between Asp283 of HPF1 and His826 of PARP-1 [39]. Additionally, mutational studies have shown two C-terminal residues of PARP-1, Leu1013, and Trp1014, dock at the back of the HPF1 C-terminal domain and contribute to complex formation [39]. All of this culminates in a joint active site that switches the substrate specificity of PARP-1 and PARP-2 from glutamate/aspartate to serine [39].

Another PARP-1 binding partner, Timeless, interacts with the PARP-1 catalytic domain via its PARP-1 binding domain [43]. Unlike HPF-1, Timeless primarily interacts with PARP-1 but not with other DDR PARPs [43]. Interestingly, rather than regulating PARP-1 overall catalytic output, the Timeless-PARP-1 interaction is required for the recruitment of Timeless to DNA lesions and to promote homologous recombination- (HR-) directed repair [43]. Knocking down PARP-1 or Timeless impairs HR, indicating that this complex is a key contributing factor in DSB repair [43].

Very recently, an arginine methyltransferase, CARM1 (also termed PRMT2), was isolated from stalled DNA replication forks where replication had been reinitiated [44]. There, it was reported to recruit and locally activate PARP-1 to stimulate PARylation at these lesions [44].

Locally-enriched PAR is key in DDR signaling

PARP-1 modifies its substrates at the site of DNA damage by repeatedly adding ADPr in three distinct enzymatic reactions. The initial attachment of the first ADPr to the carboxyl group of target protein occurs via an ester linkage. For PAR chain elongation, the subsequent ADPr moieties are added through 2',1"-O-glycosidic ribose-ribose bonds and results in linear PAR chains. Further, branching occurs between ADPr residues via 2',1" ribose-ribose bonds that create a massive network of PAR polymers [45–47].

It is important to highlight both the massive local burst of ADPr modification at the site of DNA damage, as well as its very rapid turnover (half-life of < 1 min) [48, 49]. How these locally-enriched PAR residues may contribute to a phase-separated compartment around DNA breaks in DDR signaling is gradually being revealed. The PAR polymers initiate the assembly of three intrinsically disordered proteins including FUS/TLS (fused in sarcoma/translocated in sarcoma), EWS (Ewing sarcoma), and TAF15 (TATA box-binding protein-associated factor), which are collectively abbreviated as FET. The result is a dynamic, phase-separated compartment around the DNA break [50]. FET proteins comprise two important domains that regulate phase-separated PAR accumulation around DNA lesion. Positively charged arginine– glycine–glycine (RGG) repeats act as PAR sensors while other prion-like protein domains help to phase sperate locally enriched PAR residues by liquid demixing [50]. In support of this mechanism, a mutation in the nuclear localization signal of FUS protein resulted in impaired DDR signaling and caused neurodegeneration [51]. Despite these advancements, important gaps remain in the mechanistic understanding of phase separation of PAR and its precise role in DDR signaling. Furthermore, PAR residues serve as binding sites for many repair proteins that contain PAR binding modules, allowing the streamlined recruitment of repair factors to DNA breaks [52, 53].

PARP-1 automodification and other ADP-ribosylation substrates

Among various identified ADP-ribosylation substrates, PARP-1 itself, is a major acceptor for PAR polymers [54]. PARP-1 automodification in DDR is best known for chromatin decondensation and in the recruitment of repair factors to damage site [15]. The identification of the automodification sites in PARP-1 has always been challenging due to the unstable nature of the ester linkage and variable length/branching of PAR polymers. Initially, three modification sites D387, E488, and E491 were identified in the automodification domain (AD) of PARP-1 [55] (Figure 1A). Nonetheless, a triple mutant for these sites still showed a substantial amount of PARP-1 automodification, implying the presence of other automodification sites in PARP-1 polypeptide [55]. Later, eight more automodification sites were mapped in wild type PARP-1 [56]. Recent proteomic studies have catalogued more than 50 automodification sites (Asp/Glu) in full-length PARP-1 [55–58]. However, the physiological significance of these many automodification sites present throughout PARP-1 sequence is still unclear.

While Asp and Glu residues were initially considered the primary ADPr acceptor sites, the recent progress with HPF1-mediated switch to Ser acceptor sites has challenged this view [16, 39, 40, 42]. Additionally, a comprehensive analysis that utilizes multiple unbiased approaches to determine ADP-ribosylome have demonstrated serine as a major ADP-ribosylation acceptor site [59]. Indeed, Ser-ADPr is the predominant modification in global ADP-ribosylation in response to DNA damage [60]. It is currently unclear the degree to which HPF1-directed substrate switch is specific to PARP-1 or conserved among other DDR PARPs. Indeed, this is a major emerging topic in the PARP field that requires further exploration.

Other ADP-ribosylation substrates include proteins with PAR-binding modules that mediate non-covalent interaction with PAR. For example, the FHA domain of DNA repair factors APTX and PNKP interact with the linkage of PAR chain ADPr moieties whereas XRCC1 and Ligase 4 interact via their BRCT domains with PAR chain ADPr residues, themselves [61]. We do not cover PAR binding modules in-depth, here, but the topic has been thoroughly reviewed [52, 53]. A important example of PAR binding substrate is ALC1 (amplified in liver cancer 1/CHD1L), a chromatin remodeling enzyme that interacts with PAR via its C-terminal macrodomain [62, 63]. ALC1 loss is synthetically lethal with HR deficiency [64–66] and imparts PARPi sensitivity [64–67]. In the absence of ALC1, unrepaired DNA damage results in the generation of lesions that trap both PARP-1 and PARP-2, resulting in cytotoxicity [65, 66]. This distinguishes ALC1 from other determinants of PARPi response, where PARP-1 has been reported to be the sole contributor [65], [66]. There are also some conflicting reports regarding whether ALC1 primarily acts via the release of PARP-1 [67] or PARP-2 [64] from DNA damage lesions. However, in light of findings that ALC1 loss can enhance PARPi sensitivity in either PARP-1 or PARP-2-deficient cells [65, 66], further investigation is warranted of the downstream effects of nucleosome remodeling on the release of PARP-1 and PARP-2. Altogether, these recent findings open up new avenues targeting ALC1 could be an efficient approach to overcome PARPi resistance specially in HR deficient tumors [65, 66].

Recently, DNA strand breaks themselves have been proposed to be a class of ADP-ribosylation substrate for PARP-1, PARP-2, and PARP-3 [68–70]. These DDR PARPs have the ability to perform DNA ADP-ribosylation on 5’ and 3’ terminal phosphate group or 2’-OH of a modified nucleotide of DNA break [68–70]. The terminal ends generated from DSB, SSB, nick, and/or overhangs are subjected to ADP-ribosylation [68–70]. Similar to protein ADP-ribosylation nucleotide ADP-ribosylation is a reversible process because ADPr residues are removed by several cellular hydrolases including poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) [70]. The biological significance of PARP catalyzed DNA ADP-ribosylation represents an intriguing biochemical activity to further explore.

PARP-1 automodification triggers release from DNA breaks, allowing subsequent steps in DDR

PARP-1 hyperactivation has been associated with many pathological disorders that include cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and other disorders involving inflammation [71, 72]. The transition between PARP-1 activation and inactivation is rapid and normally occurs within a few seconds of DNA damage. The automodified PARP-1 is very negatively charged (each ADPr residue carries two negative charges), and this generates an electrorepulsion between DNA and PAR polymers [73]. Thus, in one model, increased repulsion between highly negatively charged PARP-1 and DNA leads to PARP-1 dissociation from DNA, resulting in PARP-1 inactivation within 1–2 minutes of its initial binding to the DNA break [73]. One should consider an alternative model, however, wherein specific modification sites must be PARylated to specifically direct the rapid PARP-1 release from a DNA break. That said, the key primary automodification sites and their precise contribution to PARP-1 releasing mechanism remain unknown.

Furthermore, PARP-1 automodification mediated release is coupled with the recruitment of repair proteins to the damage site. XRCC1 preferentially interacts with PAR polymers via a putative phospho-binding pocket present in the BRCT I domain and is recruited to the DNA break [61, 74]. XRCC1 is a molecular scaffold protein that interacts with other repair factors (Figure 3) including PNKP, Ligase 3α, DNA polymerase β, and APTX to initiate DNA repair [75–77]. APTX and PNKP work directly on broken DNA termini [78, 79], DNA Polymerase β fills DNA gaps, and Ligase 3α finally ligates DNA nicks [75–77]. A mutation in the BRCT I domain had disrupted the interaction between XRCC1 and PAR polymers on PARP-1 and had reduced the formation of XRCC1 foci in response to oxidative DNA damage [80]. Moreover, XRCC1 foci did not appear when PARP-1 gene was genetically disrupted at exon 1 in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells [80]. Altogether, these results clearly indicated that XRCC1 recruitment to DNA lesion is PARP-1 automodification dependent.

PAR hydrolyzing enzymes

ADP-ribosylation is a reversible process that allows the rapid removal of ADPr residues from modified substrates. The removal of PAR polymers from substrates is catalyzed by PAR hydrolyzing enzymes. PAR polymers around DNA break create a massive network that allows chromatin decondensation and recruitment of repair factors. Thus, catabolism of PAR is equally important to maintain the homeostasis of PARylation.

Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) and ADP-ribosylhydrolase 3 (ARH3)

PARG is one of the first enzymes discovered that degrades PAR polymers [81, 82]. PARG removes PAR polymers via hydrolyzing the ribosyl-ribosyl bond between ADPr residues within PAR chain and at the ends through its endoglycosidase and exoglycosidase activity [17, 18, 83]. Although PARG is present in lower abundance in cells than PARP-1, it helps to maintain nuclear PAR homeostasis. For example, mice lacking the PARG gene have shown defects in DNA damage repair and caused genomic instability [84, 85]. The loss of PARG110 isoform from mouse embryonic fibroblast cells have demonstrated higher sensitivity to alkylating agents/ionizing radiation, increased micronuclei, sister chromatid exchange, and chromosome abnormalities [84]. Additionally, the disruption of the PARG gene caused early embryonic lethality in mice indicating PAR degradation is also critical for embryonic development [85].

As discussed above, PARP-1 is a predominant substrate for ADP-ribosylation in DDR, which makes PARP-1 an obvious substrate for PARG activity. PARP-1 is mostly found in the nucleus, whereas PARG is found in the nucleus and cytoplasm. PARG has three isoforms; a major isoform of 110 kDa found in nucleus and cytoplasm and two other splice variants, 102 kDa and 99 kDa, are cytoplasmic [86]. The PARG110 isoform catalyzes most of the cellular PAR hydrolysis whereas the other two variants also possess some PAR-degradation activity [82, 86]. PARG shuttles between nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments, indicating its dynamic activity to maintain nuclear PAR output [87]. Altogether, the dynamic activity of PARG110 indicates regulation of cell cycle progression through metabolism of poly-ADPr.

ARH3 has emerged more recently as a critical enzyme for the removal of PAR chains [88]. Unlike, PARG, ARH3 efficiently removes HPF1-mediated serine-directed PARylation [89, 90], and genetic removal of ARH3 leads to accumulation of serine-linked PAR chains after DNA damage [60, 90]. Thus, Glu/Asp-linked PAR is thought to be processed by PARG, while Ser-linked PAR removal relies upon a dedicated eraser, ARH3.

PARPi in cancer therapy

PARPi drugs are used to treat cancers defective in HR, especially those with BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiencies [10,11]. PARPi exploit synthetic lethality; tumors with BRCA1/2 loss of function are more sensitive to PARPi [91, 92]. Inhibition of PARP-1 activity in HR-deficient cells generates more SSBs and eventually cause replication fork collapse, thus making PARPi treatment more effective in killing tumor cells in HR deficient cells. All known PARPi bind to the NAD+ binding site of the PARP-1 catalytic domain and prevent PARP-1 automodification. Initially, it was thought that inhibiting PARP-1 catalytic activity was the primary mechanism by which PARPi kill cancer cells [93], [94]. Later, it was discovered that PARPi ‘trap’ PARP-1 in chromatin, block PARP-1 automodification directed PARP-1 release from DNA, and thus contribute to lethality [95, 96]. Paradoxically, the potency to trap PARP-1 is markedly different for all clinical PARPi despite their generally equivalent catalytic inhibition [96]. Five PARPi were analyzed for their trapping potency and were ranked from most to least: talazoparib >> niraparib > olaparib = rucaparib >> veliparib [96]. The chemical structures of these PARPi provided early hints that size and flexibility could be a contributing factors for differential PARP-1 potency (e.g. talazoparib has the most rigid structure and veliparib has the smallest structure) [96].

All clinical PARPi theoretically have the ability to promote the retention of PARP-1 on a DNA break on the basis of their potency for inhibiting PARP-1 catalytic automodification, which is required for rapid release of PARP-1 from an SSB [95, 96]. It should be noted that in cells there are at least two pools or PARP-1 at a DNA break: one which is physically bound to the break and a secondary pool that rapidly accumulates in a micron-sized region of the nucleus (i.e. with the phase separated compartment discussed, above). This likely explains why there is a disconnect in measuring the steady-state retention of PARP-1 upon potent PARPi trappers [97, 98] and the lack of an effect on the turnover rate measurable with photobleaching of GFP-tagged PARP-1 [97]. By focusing solely on the PARP-1 molecules physically bound to a SSB, however, recent biophysical and structural insights into PARPi action revealed surprising differences between different PARPi compounds in terms of how they impact the retention or release from a DNA break [98]. These PARPi-mediated effects occur via “reverse allostery” using the same network of interdomain contacts initially identified in DNA damage dependent PARP-1 activation (from catalytic domain to HD, WGR, and zinc-finger DNA binding domains) [13, 98].

The different PARPi compounds classify into at least three allosteric types (see Table 1). Type I pro-retention PARPi (EB-47 and the non-hydrolyzable NAD+ analog, benzamide adenine dinucleotide (BAD)) show a strong allosteric effect, cause further destabilization of the HD, and increase the PARP-1 affinity to the DNA break, resulting in longer PARP-1 retention on DNA break [98]. Type II PARPi (olaparib and talazoparib) are mostly neutral towards PARP-1 reverse allostery and don’t substantially modulate DNA retention beyond what is afforded by their potent catalytic inhibition that reduces automodification-dependent release [98]. Type III pro-release PARPi (veliparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) stabilize the HD and promote weaker affinity of PARP-1 for DNA, promoting PARP-1 release [98]. In terms of cytotoxicity, Type III pro-release PARPi have the potential to be less toxic to cells compared to Type I and II PARPi [98]. Type I behavior is conferred by contact of the small molecule with the HD αF helix that abuts the catalytic center of PARP-1, and a striking example of this is the addition of an extension reaching towards the αF helix that converts Type III PARPi, veliparib, to exhibiting Type I PARPi behavior in the UKTT15 derivative PARPi compound [98]. Tuning reverse allostery and PARP-1 trapping presents an intriguing avenue to develop new PARPi with novel properties that yield cellular outcomes distinct from those conferred by the current set of clinical PARPi.

Table 1.

Summary of Type I (pro-retention), II (no or mild retention), and III (pro-release) forms of PARPi.

| PARPi allosteric types [98] | PARPi compounds | Allosteric effect on binding to broken DNA [98] | Catalytic inhibition | Automodification-dependent release | Outcome of allosteric effect on HR deficiency-dependent cell toxicity [98] | Allosterically tuned for cancer treatment | Allosterically tuned for cytoprotection from hyperactive PARP-1 in inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | EB-47 BAD |

Allosteric pro-retention • Destabilized HD • Increased affinity for DNA break |

+++ | − | +++ | +++ | − |

| Type II | Olaparib Talazoparib |

Non-allosteric • Little or no HD destabilization • Little or no increase in affinity for DNA break |

+++ | − | + | + | +/− |

| Type III | Niraparib Rucaparib Veliparib |

Allosteric pro-release • Stabilized HD • Reduced affinity for DNA break |

+++ | − | − | − | +++ |

Concluding Remarks

Among all PARP family members, PARP-1 has been extensively studied for its role in DNA damage repair. PARP-1 is a primary signaling factor in DDR, making it a first-line target for the treatment of high-grade breast and ovarian cancer with homologous recombination deficiency. In this review, we have covered the “life cycle” of PARP-1 in its most appreciated role as a DDR signaling molecule. Emerging research directions include identifying the precise role of accessory factors in regulating PARP-1 activity, determining the nature of automodification-dependent PARP-1 silencing, assessing the physiological significance of PARP-1 substrate specificity, and more (see Outstanding Questions). Recent progress has highlighted the unexpected ways in which small molecule inhibitors can be designed to tune one particular step in the cycle, as well as how accessory factors modulate other steps in yet new ways that open the door to unexplored ways to therapeutically target PARP-1 in the context of an expanding list of prevalent human diseases.

Outstanding Questions.

Does PARylation of chromatin near DNA breaks create a phase-separated compartment that contributes to downstream recruitment of DNA damage response (DDR) factors?

What important accessory factors interact with PARP-1 and how do they modulate its catalytic activity for DDR signaling?

What molecular steps are involved in silencing PARP-1 and releasing from a DNA break after signaling is complete?

How do PARP-1, ADP-ribosylhydrolase 3 (ARH3), and Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) function in concert during early events in DDR?

How can tuning reverse allostery be utilized to design small molecule inhibitors that target PARP-1 for specific therapeutic outcomes in the growing list of diseases where PARP inhibitors (PARPi) are being used and tested in the clinic?

Highlights.

DNA damage caused by endogenous and exogenous factors is a major source of genomic instability, thus DNA damage response is critical to maintaining the integrity of the genome.

The rapid detection of DNA damage by PARP-1 and its PARylation of local substrates initiates DNA repair signaling.

Recent works illuminated how regulation of PARP-1 include an allosteric mechanism where 1000-fold activation upon engaging DNA breaks occurs via destabilization of the helical domain to relieve autoinhibition of the catalytic site, PARP-1 automodification, and interaction with factors such as HPF1, CARM1, and PAR hydrolyzing enzymes.

HPF1 modulates PARP-1 enzymatic activity to target Ser side-chains rather than Asp/Glu.

The realization that PARP-1 retention and release from DNA can be allosterically tuned depending on the type of PARPi opens up new avenues for therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank our UPenn colleagues J. Dawicki-McKenna, R. Billur, and P. Verma for comments on the manuscript and acknowledge funding from the NIH (GM130302 to B.E.B.).

Glossary

- ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART)

an enzyme that catalyzes ADP-ribosylation

- DNA damage response (DDR)

a cellular pathway activated in response to DNA damage to detect and repair the lesion

- Homologous recombination (HR)

a method of genetic recombination where nucleotide sequences are exchanged between two similar or identical DNA strands

- Hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry (HXMS)

an approach that utilizes mass spectrometry to study protein structure and interaction in a solution. Backbone amide hydrogens are exchanged with deuterium from heavy water (D2O) comprising the buffer, and the exchange rate is measured over time as an increase in mass for each peptide derived from the protein under investigation

- PARylation

a type of post-translational modification where polymers of ADP-ribose are covalently attached to the target protein

- PARP inhibitor (PARPi)

small molecule inhibitors of PARP-1

- PAR

poly(ADP-ribose)

- Post-translational modification

a covalent modification that occurs on a side chain of a protein after translation, mostly catalyzed by a specific group of enzymes

- MARylation

a type of post-translational modification where a single ADP-ribose is covalently attached to the target protein

- Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

a repair pathway where double-strand break ends are repaired without homologous DNA templates

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Gibson BA and Kraus WL (2012) New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol 13, 411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Amé JC et al. (2004) The PARP superfamily. Bioessays 26, 882–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chambon JD et al. (1963) Nicotinamide mononucleotide activation of new DNA-dependent polyadenylic acid synthesizing nuclear enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 11, 39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Amé JC et al. (1999) PARP-2, A novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J. Biol. Chem 274, 17860–17868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rulten SL et al. (2011) PARP-3 and APLF function together to accelerate nonhomologous end-joining. Mol. Cell 41, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vyas S et al. (2014) Family-wide analysis of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity. Nat. Commun 5, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ludwig A et al. (1988) Immunoquantitation and size determination of intrinsic poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase from acid precipitates. An analysis of the in vivo status in mammalian species and in lower eukaryotes. J. Biol. Chem 263, 6993–6999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gourley C et al. (2020) Role of Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase inhibitors beyond BReast CAncer Gene-mutated ovarian tumours: definition of homologous recombination deficiency? Curr. Opin. Oncol 32, 442–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Golan T et al. (2014) Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br. J. Cancer 111, 1132–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Farmer H et al. (2005) Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bryant HE et al. (2005) Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434, 913–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Satoh MS and Lindahl T (1992) Role of poly(ADP-ribose) formation in DNA repair. Nature 356, 356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dawicki-McKenna JM et al. (2015) PARP-1 activation requires local unfolding of an autoinhibitory domain. Mol. Cell 60, 755–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Langelier M-F et al. (2018) NAD+ analog reveals PARP-1 substrate-blocking mechanism and allosteric communication from catalytic center to DNA-binding domains. Nat. Commun 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chaudhuri AR and Nussenzweig A. (2017) The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18, 610–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gibbs-Seymour I et al. (2016) HPF1/C4orf27 Is a PARP-1-Interacting Protein that Regulates PARP-1 ADP-Ribosylation Activity. Mol. Cell 62, 432–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miwa M et al. (1974) Purification and properties of glycohydrolase from calf thymus splitting ribose-ribose linkages of poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose). J. Biol. Chem 249, 3475–3482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ikejima M and Gill DM (1988) Poly(ADP-ribose) degradation by glycohydrolase starts with an endonucleolytic incision. J. Biol. Chem 263, 11037–11040 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lilyestrom W et al. (2010) Structural and biophysical studies of human PARP-1 in complex with damaged DNA. J. Mol. Biol 395, 983–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Langelier M-F et al. (2010) The Zn3 domain of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) functions in both DNA-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis activity and chromatin compaction. J. Biol. Chem 285, 18877–18887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Murcia JM-De et al. (1989) Zinc-binding domain of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase participates in the recognition of single strand breaks on DNA. J. Mol. Biol 210, 229–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Langelier M-F et al. (2011) Crystal structures of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) zinc fingers bound to DNA: structural and functional insights into DNA-dependent PARP-1 activity. J. Biol. Chem 286, 10690–10701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ikejima M et al. (1990) The zinc fingers of human poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase are differentially required for the recognition of DNA breaks and nicks and the consequent enzyme activation. Other structures recognize intact DNA. J. Biol. Chem 265, 21907–21913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Haince J-F et al. (2008) PARP1-dependent kinetics of recruitment of MRE11 and NBS1 proteins to multiple DNA damage sites. J. Biol. Chem 283, 1197–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eustermann S et al. (2015) Structural Basis of Detection and Signaling of DNA Single-Strand Breaks by Human PARP-1. Mol. Cell 60, 742–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Langelier M-F et al. (2012) Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science 336, 728–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Langelier M-F and Pascal JM (2013) PARP-1 mechanism for coupling DNA damage detection to poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 23, 134–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Langelier M-F et al. (2014) PARP-2 and PARP-3 are selectively activated by 5' phosphorylated DNA breaks through an allosteric regulatory mechanism shared with PARP-1. Nucleic. Acids. Res 42, 7762–7775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Riccio AA et al. (2016) PARP-2 domain requirements for DNA damage-dependent activation and localization to sites of DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 1691–1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Obaji E et al. (2020) Activation of ARTD2/PARP2 by DNA damage induces conformational changes relieving enzyme autoinhibition. bioRxiv, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schreiber V et al. (2002) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 (PARP-2) is required for efficient base excision DNA repair in association with PARP-1 and XRCC1. J. Biol. Chem 277, 23028–23036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen Q et al. (2018) PARP2 mediates branched poly ADP-ribosylation in response to DNA damage. Nat Commun 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ronson GE et al. (2018) PARP1 and PARP2 stabilise replication forks at base excision repair intermediates through Fbh1-dependent Rad51 regulation. Nat Commun 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Murcia J.M-De et al. (2003) Functional interaction between PARP-1 and PARP-2 in chromosome stability and embryonic development in mouse. EMBO. J 22, 2255–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ogden TEH et al. (2020) Dynamics of the HD regulatory subdomain of PARP-1; substrate access and allostery in PARP activation and inhibition. bioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Walker JR et al. (2001) Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair. Nature 412, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yang G et al. (2018) Super-resolution imaging identifies PARP1 and the Ku complex acting as DNA double-strand break sensors. Nucleic. Acids. Res 46, 3446–3457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schmutz I et al. (2017) TRF2 binds branched DNA to safeguard telomere integrity. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 24, 734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Suskiewicz MJ et al. (2020) HPF1 completes the PARP active site for DNA damage-induced ADP-ribosylation. Nature 579, 598–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bonfiglio JJ et al. (2017) Serine ADP-Ribosylation Depends on HPF1. Mol. Cell 65, 932–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bilokapic S et al. (2020) Bridging of DNA breaks activates PARP2-HPF1 to modify chromatin. Nature 585, 609–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Leung AKL (2017) SERious Surprises for ADP-Ribosylation Specificity: HPF1 Switches PARP1 Specificity to Ser Residues. Mol. Cell 65, 777–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xie S et al. (2015) Timeless Interacts with PARP-1 to Promote Homologous Recombination Repair. Mol. Cell 60, 163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Genois M-M et al. (2020) CARM1 regulates replication fork speed and stress response by stimulating PARP1. Mol Cell Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Juarez-Salinas H et al. (1982) Poly(ADP-ribose) has a branched structure in vivo. J. Biol. Chem 257, 607–609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rolli V et al. (1997) Random mutagenesis of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase catalytic domain reveals amino acids involved in polymer branching. Biochemistry 36, 12147–12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Alemasova EE and Lavrik OI (2019) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. Nucleic. Acids. Res 47, 3811–3827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wielckens K et al. (1983) Stimulation of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation during Ehrlich ascites tumor cell ‘starvation’ and suppression of concomitant DNA fragmentation by benzamide. J. Biol. Chem 258, 4098–4104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Alvarez-Gonzalez R and Althaus FR (2018) Poly(ADP-ribose) catabolism in mammalian cells exposed to DNA-damaging agents. Mutat. Res 218, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Altmeyer M et al. (2015) Liquid demixing of intrinsically disordered proteins is seeded by poly(ADP-ribose). Nat. Commun 6, 8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Naumann M et al. (2018) Impaired DNA damage response signaling by FUS-NLS mutations leads to neurodegeneration and FUS aggregate formation. Nat. Commun 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zaja R et al. (2012) Molecular Insights into Poly(ADP-ribose) Recognition and Processing. Biomolecules 3, 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu C et al. (2017) The role of poly ADP-ribosylation in the first wave of DNA damage response. Nucleic. Acids. Res 45, 8129–8141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ogata N et al. (1981) Poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase, a main acceptor of poly(ADP-ribose) in isolated nuclei. J. Biol. Chem 256, 4135–4137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Tao Z et al. (2009) Identification of the ADP-ribosylation sites in the PARP-1 automodification domain: analysis and implications. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 14258–14260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chapman JD (2013) Mapping PARP-1 auto-ADP-ribosylation sites by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteome. Res 12, 1868–1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gagné J-P et al. (2015) Quantitative site-specific ADP-ribosylation profiling of DNA-dependent PARPs. DNA. Repair. (Amst.) 30, 68–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sharifi R et al. (2013) Deficiency of terminal ADP-ribose protein glycohydrolase TARG1/C6orf130 in neurodegenerative disease. EMBO J 32, 1225–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hendriks IA et al. (2019) An Advanced Strategy for Comprehensive Profiling of ADP-ribosylation Sites Using Mass Spectrometry-based Proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 18, 1010–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Palazzo L et al. (2018) Serine is the major residue for ADP-ribosylation upon DNA damage. Elife 7, e34334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Li M et al. (2013) The FHA and BRCT domains recognize ADP-ribosylation during DNA damage response. Genes. Dev 27, 1752–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ahel D et al. (2009) Poly(ADP-ribose)-dependent regulation of DNA repair by the chromatin remodelling enzyme ALC1. Science 325, 1240–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gottschalk AJ et al. (2009) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation directs recruitment and activation of an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 13770–13774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Blessing C. et al. (2020) The Oncogenic Helicase ALC1 Regulates PARP Inhibitor Potency by Trapping PARP2 at DNA Breaks. Mol Cell 80, 862–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Verma P et al. (2021) ALC1 links chromatin accessibility to PARP inhibitor response in homologous recombination deficient cells. Nat Cell Biol, online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hewitt G et al. (2020) Defective ALC1 nucleosome remodeling confers PARPi sensitization and synthetic lethality with HRD. Mol Cell Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Juhász S et al. (2020) The chromatin remodeler ALC1 underlies resistance to PARP inhibitor treatment. Sci Adv 6, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Talhaoui I et al. (2016) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases covalently modify strand break termini in DNA fragments in vitro. Nucleic. Acids. Res 44, 9279–9295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zarkovic G et al. (2018) Characterization of DNA ADP-ribosyltransferase activities of PARP2 and PARP3: new insights into DNA ADP-ribosylation. Nucleic. Acids. Res 46, 2417–2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Munnur D and Ahel I (2017) Reversible mono-ADP-ribosylation of DNA breaks. FEBS. J 284, 4002–4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Narne P et al. (2017) Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 hyperactivation in neurodegenerative diseases: The death knell tolls for neurons. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol 63, 154–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Singh N et al. (2020) Therapeutic Strategies and Biomarkers to Modulate PARP Activity for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ferro AM et al. (1982) Poly(ADP-ribosylation) in vitro. Reaction parameters and enzyme mechanism. J. Biol. Chem 257, 7808–7813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Breslin C et al. (2015) The XRCC1 phosphate-binding pocket binds poly (ADP-ribose) and is required for XRCC1 function. Nucleic Acids Res 43, 6934–6944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Caldecott KW et al. (1994) An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol. Cell. Biol 14, 68–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Marintchev A et al. (2000) Domain specific interaction in the XRCC1-DNA polymerase beta complex. Nucleic. Acids. Res 28, 2049–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Whitehouse CJ et al. (2001) XRCC1 stimulates human polynucleotide kinase activity at damaged DNA termini and accelerates DNA single-strand break repair. Cell 104, 107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Jilani A et al. (1999) Molecular cloning of the human gene, PNKP, encoding a polynucleotide kinase 3’-phosphatase and evidence for its role in repair of DNA strand breaks caused by oxidative damage. J Biol Chem 274, 24176–24186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ahel I et al. (2006) The neurodegenerative disease protein aprataxin resolves abortive DNA ligation intermediates. Nature 443, 713–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].El-Khamisy SF et al. (2003) A requirement for PARP-1 for the assembly or stability of XRCC1 nuclear foci at sites of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic. Acids. Res 31, 5526–5533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Miwa M and Sugimura T (1971) Splitting of the Ribose-Ribose Linkage of Poly(Adenosine Diphosphate-Ribose) by a Calf Thymus Extract. J. Biol. Chem 246, 6362–6364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ueda K et al. (1972) Poly ADP-ribose glycohydrolase from rat liver nuclei, a novel enzyme degrading the polymer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 46, 516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Barkauskaite E et al. (2013) Visualization of poly(ADP-ribose) bound to PARG reveals inherent balance between exo- and endo-glycohydrolase activities. Nat Commun, 4, 2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Min W et al. (2010) Deletion of the nuclear isoform of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG) reveals its function in DNA repair, genomic stability and tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 31, 2058–2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Koh DW et al. (2004) Failure to degrade poly(ADP-ribose) causes increased sensitivity to cytotoxicity and early embryonic lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 17699–17704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Meyer-Ficca ML et al. (2004) Human poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase is expressed in alternative splice variants yielding isoforms that localize to different cell compartments. Exp. Cell. Res 297, 521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Ohashi S et al. (2003) Subcellular localization of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase in mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 307, 915–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Oka S et al. (2006) Identification and characterization of a mammalian 39-kDa poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. J Biol Chem 281, 705–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Bonfiglio JJ et al. (2020) An HPF1/PARP1-Based Chemical Biology Strategy for Exploring ADP-Ribosylation. Cell 183, 1086–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Fontana P. et al. (2017) “Serine ADP-ribosylation reversal by the hydrolase ARH3. Elife 6, e28533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Miki Y et al. (1994) A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 266, 66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Wooster R et al. (1995) Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature 378, 789–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Kummar S et al. (2012) Advances in using PARP inhibitors to treat cancer. BMC. Med 10, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Chuang H-C et al. (2012) Differential anti-proliferative activities of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast. Cancer. Res. Treat 134, 649–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Murai J et al. (2012) Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res 72, 5588–5599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Pommier Y et al. (2016) Laying a trap to kill cancer cells: PARP inhibitors and their mechanisms of action. Sci. Transl. Med 8, 362ps17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Shao Z et al. (2020) Clinical PARP inhibitors do not abrogate PARP1 exchange at DNA damage sites in vivo. Nucleic. Acids. Res 48, 9694–9709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Zandarashvili L et al. (2020) Structural basis for allosteric PARP-1 retention on DNA breaks. Science 368, eaax6367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]