Abstract

Certain organ-on-a-chip (OoC) systems have been validated to show superior predictive capabilities compared to planar, static cell cultures, and animal models for drug evaluations. One of the ongoing initiatives led by OoC developers is bridging the academia-to-industry gap in hope of gaining wider adoption by end-users: academic biological researchers and industry. In this article, we discuss several recommendations that can help drive the translation of OoC in the market. We first lay out some of the key challenges faced by OoC developers before highlighting some of the existing advances in OoC platforms. Thereafter, we suggest recommendations that OoC developers can deliberate for the translation of OoC into the industry.

Potential of Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) in Drug Development

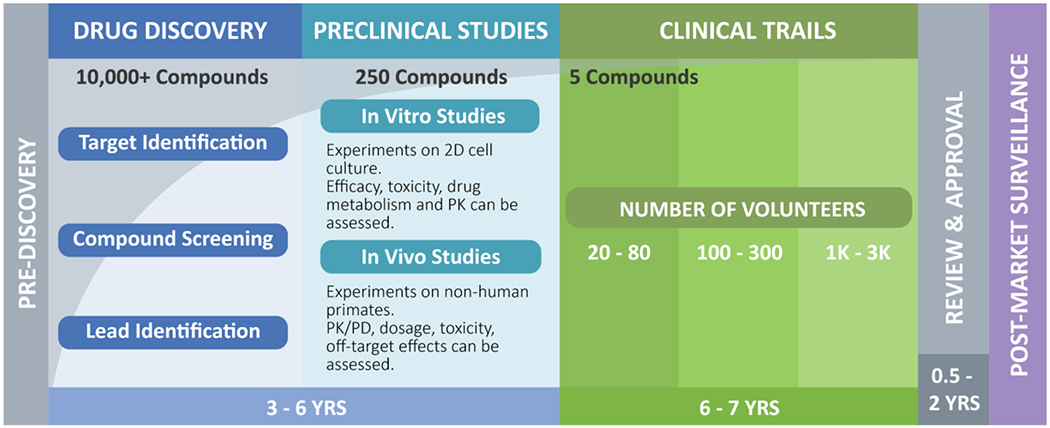

Taking a drug from the discovery to the market is a long and arduous journey (Fig. 1) [1]. A drug goes through at least five stages before reaching the market: pre-discovery, drug discovery, preclinical studies, clinical trials, review, and approval, and then are continuously being monitored to ensure safety. Since the thalidomide disaster in 1960 [2], regulatory agencies have emphasized the requirement for rigorous toxicity testing during drug development. Before a drug enters a clinical trial, it must be deemed safe or specific risk-assessed to balance between benefits and harms [3]. To do so, the drug undergoes a series of stringent tests in two-dimensional (2D) cellular assays and studies on animal models such as non-human primates. While these traditional methods successfully bring drugs to the market, more than 80% of drugs tested in humans fail to demonstrate safety and efficacy (see Glossary) in clinical trials [4–7]. Studies have consistently found that existing preclinical tests are a poor indicator of human responses [8–10]. The limitations in the existing 2D cellular assays and animal models prompted scientists to develop models with better predictive capabilities.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the typical drug development process.

Organ-on-a-chip (OoC) is one such technology. OoC is an in vitro high-content system aimed at recapitulating in vivo organ-level functions by mimicking a physiologically relevant microenvironment in a microfluidic (or equivalent) device. By using actual human cells in platforms analogous to their native microenvironments, scientists postulated that OoCs would offer the potential to become better predictors of human responses to adverse drug effects than conventional 2D or animal models. Over the last 15 years since their implementation, countless OoCs have to various degrees recapitulated human physiology and pathology. They have demonstrated clinically relevant responses of drugs with a level of fidelity that is oftentimes as good as, or sometimes better than, animal models [7].

From an engineering perspective, OoCs have been primed by the microfluidics community to be a killer application [11, 12]. By definition, a killer application refers to a technology or product that is presented as indispensable and much superior to its predecessor. Developments in OoCs have indeed been proven that these platforms have the potential to substantiate their designation as a killer application, as they have been validated to show superior predictive capabilities to 2D cell cultures and oftentimes animal models [13, 14].

The roles of OoCs are multifaceted. We not only expect OoCs to make strides in accelerating the development of new drugs and advance personalized medicine, but also anticipate its contribution in basic sciences (i.e., understanding pathophysiology of rare diseases) [15, 16]. Out of the many initiatives in the field of the OoC, one ongoing effort is bridging the academia-to-industry gap to gain wider adoption among the ultimate end-users of OoCs: academic researchers and industry [17]. While not all OoC platforms necessitate considerations for academia-to-industry translation, this article focuses on recommendations for OoC developers when developing OoCs for translational purposes. We start by introducing the challenges faced when developing OoCs for drug development. We also discuss the advances in the field of the OoC by highlighting the key hallmarks emphasized in the development of OoCs.

Challenges and Need of OoC Development

Complexity of Human Physiology

To appreciate the magnitude of the challenge in predicting human responses to drug candidates, one needs to understand the complexity of human physiology and what happens to the drug after it is administered. Furthermore, OoC developers need to understand the requirements as mandated by regulatory agencies. For instance, evaluations on the drug pharmacology, in vivo efficacy, and toxicology tests using standard 2D cellular assays, animal models, and in silico models are usually a requirement in the preclinical phase [18, 19]. We frame these challenges and requirements into three perspectives: (i) the effects of the body on the drug, (ii) the effects of the drug on the body, and (iii) mechanisms leading to drug-induced toxicity.

The effects of the body on the drug.

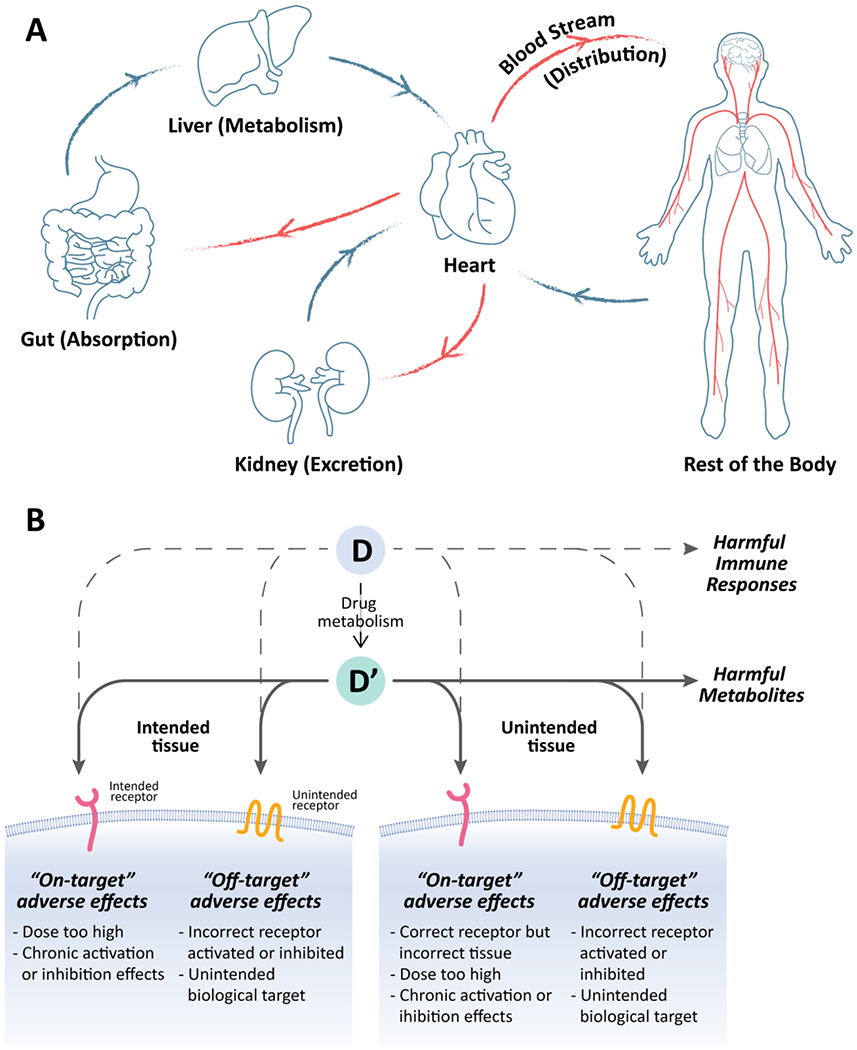

The study and characterization of how the body affects the fate of the drug are usually known in pharmacology as pharmacokinetics (PK). The human body is a complex, highly interlinked system, and a drug administered to a human goes through at least four processes that include absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [20]. For example, when a drug is administered orally, the compound is first absorbed through the gut and enters the bloodstream, where it is distributed throughout the fluid and tissues in the body, further metabolized (usually in the liver) and finally excreted from the body (usually through the kidneys) (Fig. 2A). One of the most common metrics measured in PK is the concentration of drugs circulating in the body over time. An equally important measurement is the bioavailability of a drug, that is, the fraction of the administered drug that reaches the targeted site of action [21].

Figure 2.

A) Schematic diagram illustrating the ADME within the human circulation system. B) Schematic diagram illustrating the various mechanism of drug-induced toxicity. D: drug, D’: drug metabolite.

The effects of the drug on the body.

The study and characterization of how the drug affects the body are known in pharmacology as pharmacodynamics (PD). Importantly, after the drug enters the body, it becomes crucial to understand if the drug is efficacious and safe. For example, how might a drug course through a whole body to (i) specifically target a diseased organ (efficacy) and (ii) discriminate between its intended target and other parts of the host (safety)? Furthermore, just like the famous dictum coined by Paracelsus (a Swiss physician in the 15th century) “the dose makes the poison,” the difference between efficacy and adverse toxic effects is a matter of dosage (i.e., therapeutic window). PK and PD are usually studied together, and they include important readouts that ultimately influence dosing, benefit, and adverse effects [22, 23].

Mechanisms leading to drug-induced toxicity.

Further adding to the challenges in developing OoCs, a drug can cause adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or drug-induced toxicity in more than one mechanism. These mechanisms can be interrelated, and using existing single-tissue models to predict drug-induced toxicity may not be able to accurately represent all these events. Briefly, mechanisms that can lead to drug-induced toxicity are (i) on-target adverse effects, (ii) off-target adverse effects, (iii) harmful metabolites, (iv) harmful immune responses, and (v) idiosyncratic drug reaction (Fig. 2B) [24], On-target adverse effects refer to a drug binding to its intended receptor but at an inappropriate dosage. Alternatively, the drug may bind to the intended receptor but in an incorrect tissue. These events may result in a biological response that produces toxic effects. Secondly, off-target effects refer to a drug binding to an unintended target, regardless of the tissue, resulting in adverse effects. Third, almost all drug compounds are metabolized, usually in the liver, and may produce a harmful metabolite. Harmful immune responses manifest as the fourth mechanism that can cause drug-induced toxicity. The two primary immune mechanisms that can elicit adverse effects are allergic response and autoimmune reaction. Lastly, idiosyncratic drug reactions (IDRs) can happen to a small population of patients. As IDRs are usually very rare, these events are difficult to predict using existing models.

Limitations of 2D Cellular Assays and Animal Models

The complexity of human biology and multiple modes of toxicity suggests the difficulty of predicting adverse drug effects in preclinical testing. While the current tools, 2D cell cultures, and animal models, have successfully brought numerous drugs to the market, it is undeniable that a more predictable tool is needed. For example, 2D cellular assays of a homogeneous population of cells cultured on a planar surface do not recapitulate human organs to allow accurate prediction capabilities. Human organs are assembled with various specialized cell types arranged in precise geometries with specific microenvironments. Furthermore, PK/PD or ADME studies cannot be meaningfully carried out as organ-organ interactions are not represented in 2D cellular assays.

To characterize the PK/PD or ADME of a drug candidate in the conventional sense, living animals must be used. Unfortunately, differences in the underlying molecular, cellular, and physiological mechanism between animals and humans may result in the inaccurate prediction of human drug responses. Furthermore, animal models require high financial investments, and they are usually not amenable for real-time monitoring of PK/PD profiles. [25]

How Do OoCs Aim to Fill the Gap?

There is a dire need to find a more predictive model than the current 2D cellular assays and animal models. As early as 1996, scientists began to propose and demonstrate the concept of cell culture analogues (CCAs) or OoCs [26–31]. OoC is a technology that marries engineering disciplines such as microfluidics with advances in developmental biology and tissue engineering. Recapitulating key organ-level functions in vitro is by no means a simple endeavor given the complexity of human physiology. Therefore, there are several milestones that researchers must meet. In the short term, the focus would include developing well-characterized and validated individual organ systems (i.e., liver, kidney, etc.) [32]. In the long term, the vision is to develop a “human-body-on-a-chip” system, where multiple organ models are fluidically linked to allow for the study of inter-dependent PK, PK/PD, and ADME relationships that can benefit safety and toxicity assessments [33, 34].

Existing OoC Platforms

Biomimicry – Key Hallmarks in OoCs

Biomimicry –

creating an environment close enough to their native environment with precise configuration in a compartmentalized, and often non-planar manner, so that human cells function like their native counterparts – is crucial in understanding highly complex human physiology. There are several key hallmarks that OoC developers aim to replicate, namely the mimicry of (i) fluid flow, (ii) mechanical stimulus, (iii) three-dimensional (3D) spatial organization of cells, and (iv) crosstalk between cells/organs.

Mimicking fluid flow.

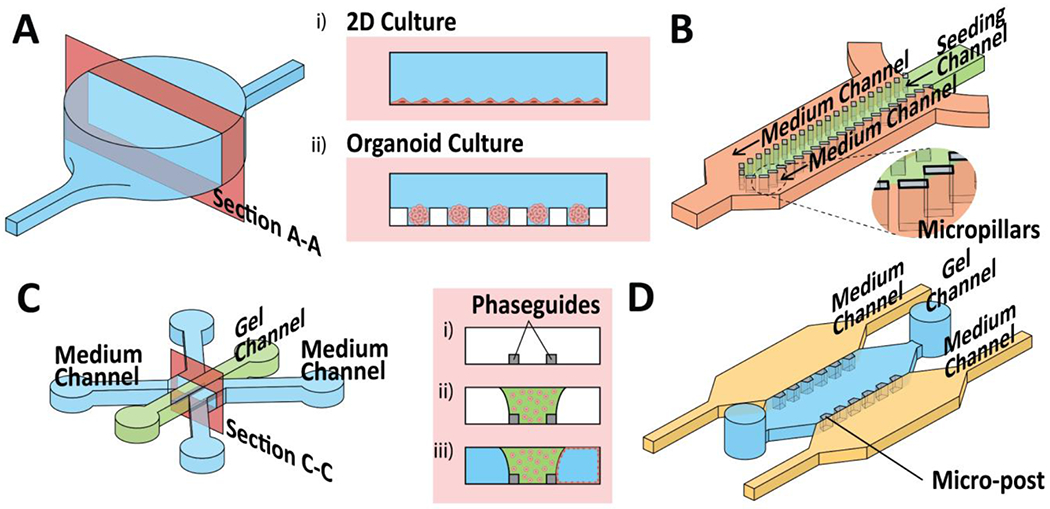

The first key hallmark of biomimicry found in OoCs is fluidic flow, analogous to vasculature where its main function is to transport nutrients, oxygen and at the same time, remove waste products and CO2. The bloodstream is the primary route where drug compounds are distributed across the whole body. Furthermore, fluid shear stress has been established to affect the phenotype and morphology of cells [35]. Therefore, to recapitulate key functions of organs, fluid control within OoCs is crucial. The challenge then lies in integrating cells in the presence of fluid flow. The most traditional form of integration is the direct seeding of cells or organoids on the surface of the microfluidic channels (Fig. 3Ai–ii) [36], The method of direct seeding depends mainly on the self-attachment capabilities of adherent cells [37]. Another technique is the use of physical barriers to constrict cells or spheroids in the “cell compartment” while allowing the medium to flow in the adjacent channels to permit nutrient exchange (Fig. 3B) [38, 39], Alternatively, instead of relying on their self-attachment capabilities, the cells can be encapsulated within a hydrogel-based extracellular matrix (ECM) with the help of microfluidic channels (Fig. 3C–D) [40–43], For example, we encapsulated tumor cells within a hydrogel matrix and incorporated them further with bioprinted fluidic channels to mimic fluid flow analogous to both blood vascular perfusion and lymphatic drainage flow [44]. As the hydrogels employed (e.g., collagen, Matrigel, gelatin, and fibrin) are usually highly porous, the hydrogels are highly permeable to medium exchange and biomolecules. The methods mentioned earlier involve artificially creating the channel architecture that mimics a vasculature. However, by using OoCs (Fig. 3D), researchers can use the inherent capabilities of endothelial cells – angiogenic sprouting of the microvasculature network within the ECM to mimic the multiscale fluid distribution and fluid flow [45–47].

Figure 3.

A) Schematic representation of a microfluidic culture chamber and cross-sectional illustration of i) 2D planar cell culture and ii) organoid culture. B) Schematic representation of a microfluidic device with micropillars to constrain cells/organoids within the seeding channel. C) Schematic representation of the 3-lane OrganoPlate® (Mimetas) consisting of two medium channels (represented in blue) and a single gel channel (depicted in green). The cross-sectional view (Section C-C) illustrates the multiple steps in i-ii) seeding the ECM gel and iii) subsequent seeding of a monolayer of barrier tissues in the medium channel. D) Schematic representation of the 3D Cell Culture Chip (AM Biotech) that consists of micro-post array to confine gel within the gel channel (represented in blue).

Mimicking mechanical stimulus.

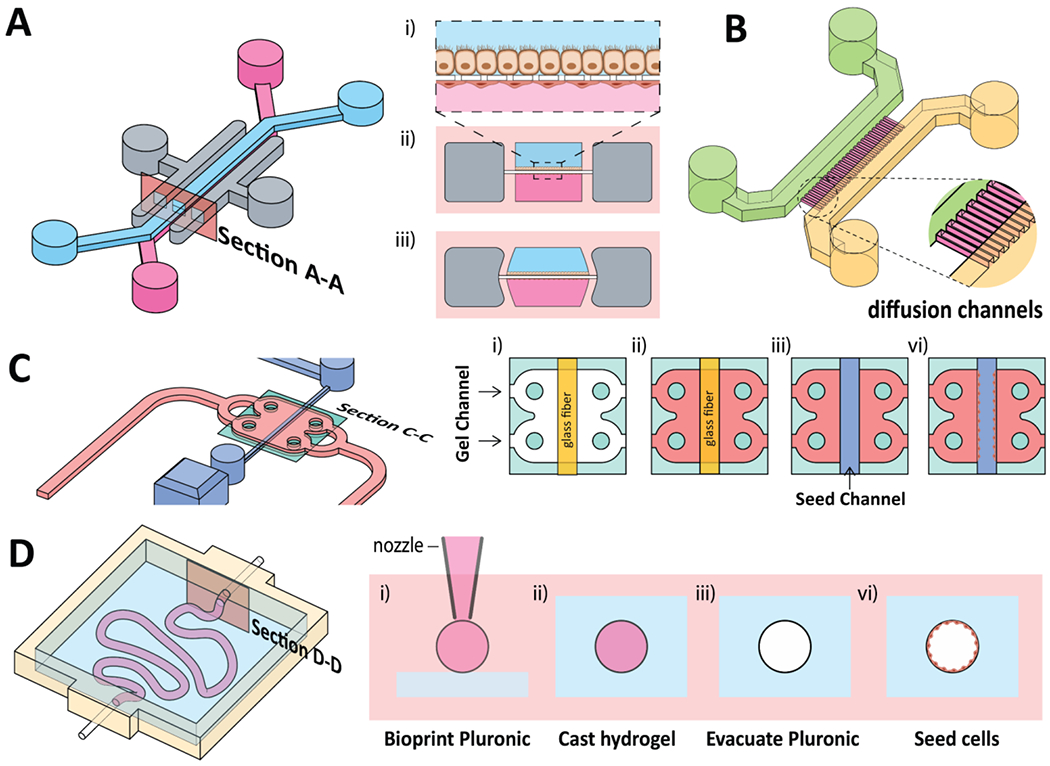

Another hallmark of biomimicry found in OoC is the ability to incorporate mechanical stimulation. Several organs, including the lung, blood vessel, and intestinal tract, are not stationary in vivo but experience cyclical motions vital to their functions. Additionally, mechanical forces affect cell behaviors, including growth, differentiation, programmed cell death, and migration [35, 48]. One of the most representative platforms for on-chip mechanical stimulus was demonstrated by Ingber’s group, as shown by the lung-on-a-chip that incorporates the cyclical stretching motions analogous to the breathing motions in human lungs [28]. The stretching motion was performed by incorporating vacuum channels on the sides of a porous membrane where relevant cells (epithelial and endothelial) are seeded (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the mimicry of cyclic mechanical strains was found to accentuate toxic and inflammatory responses of the lung to silica nanoparticles. Other platforms mimicking the mechanical movement of the lung have been demonstrated [49]. Different cell types (i.e., Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells) were also shown using a similar chip architecture [16, 50, 51].

Figure 4.

A) Schematic representation of the lung-chip (Emulate) and the cross-sectional view (section A-A) illustrating i) porous membrane with epithelial cells on the top side and endothelial cells on the bottom, ii-iii) mechanical stretching of the porous membrane when negative pressure is applied in the vacuum channel (depicted in grey). B) Schematic representation of OoC incorporated with diffusion channels. C) Schematic representation of the ParVivo chip (Nortis) and the cross-sectional view (section C-C) illustrating i-ii) casting hydrogel (pink) via the gel channel with a glass fiber to form lumen structure within chip, and iii-vi) seeding of barrier tissue within the lumen cavity. D) Schematic representation of a bioprinted kidney proximal tubule and the cross-sectional view (section D-D) illustrating i) 3D printing of sacrificial Pluronic filament, ii) casting of surrounding hydrogel, iii) evacuating of the Pluronic filament and, vi) seeding of cells in the lumen cavity.

Mimicking 3D spatial organization.

The next hallmark of biomimicry in OoC is the 3D spatial organization of cells. Various specialized cell types are arranged in precise geometries and interacting with specific microenvironments. It has been established that cells cultured in 2D differ from cells cultured in 3D in terms of morphology, including at the expression levels of a variety of proteins [52, 53]. There are two main types of tissue organizations that researchers focus on, namely, parenchymal tissues and barrier tissues [25].

In the context of ADME, mimicking parenchymal tissues is of great interest because they are usually responsible for the function of a particular organ. For example, hepatocytes belong to the parenchymal tissue of the liver, which plays a pivotal role in metabolism, detoxification, and protein synthesis. Organ-specific parenchymal tissues are typically densely packed and precisely organized to exhibit organ-specific functions. In OoC technology, parenchymal tissue types (i.e., cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes) are oftentimes incorporated on-chip with the help of 3D ECM [54, 55]. These cells are mixed with uncured hydrogels and injected into the microfluidic channels before allowing them to cure. Crucially, flanking channels are usually required to facilitate the flow of the medium necessary to maintain the cells within the hydrogel matrices. Surface tension was employed to enable the confinement of cell-laden hydrogel within their predetermined channels. For example, cell culture chips developed by Kamm’s group and commercialized by AIM Biotech used micropillars to confine cell-laden hydrogel in their respective channels (Fig. 3D) [41, 47, 56]. Mimetas, a platform that uses phaseguide™ technology can also be used to confine cell-laden hydrogel in their respective channels (Fig. 3C) [57]. Alternatively, ECM can be first coated on a porous membrane to allow the attachment and self-assembly of parenchymal tissues [58–60].

Barrier tissues are also of great importance to researchers because they are essential in understanding the absorption, first-pass metabolism, excretion, and toxicity of drugs across tissue-blood or tissue-tissue boundaries. A review by Sakolish et al. highlights the progress and challenges in modeling tissue barriers in OoC [61]. Briefly, mimicking barrier tissues (e.g., endothelial cells, epithelial cells) are usually attained by using porous membranes. The most common porous membrane configuration is the Transwell® inserts that are optimized to be used in conjunction with well-plates [62]. Companies including CN Bio [63, 64] and TissUse [65] utilize Transwell® inserts as part of their OoC platforms. Alternatively, the OoCs demonstrated by Ingber’s group incorporate porous polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane between two separate microfluidic channels (Fig. 4A). The advantage of this chip architecture is the ability to incorporate a second cell type on the underside of the membrane. For example, this chip architecture allows the inclusion of an endothelial barrier on one side, and a secondary cell type (e.g., liver, kidney, bone marrow, gut) on the other side of the porous membrane. Besides using the porous membrane, barrier tissues can also be seeded on a pre-fabricated lumen structure, akin to the structure in vivo (e.g., vasculature, proximal kidney tubule). Several strategies exist that involve seeding barrier tissues on pre-fabricate lumen structures using hydrogel ECMs. The fabrication of the lumen structures may involve (i) casting hydrogel by using glass fiber as a template (Fig. 4C) [66], (ii) 3D bioprinting of a sacrificial filament that can be evacuated after casting the surrounding hydrogel (Fig. 4D) [67–69], or (iii) confining hydrogels in respective chambers using phaseguide™ technology (Fig. 3C) [70, 71]. In these setups, parenchymal cells can be encapsulated within the surrounding hydrogels (gel channels, Fig. 4C, D), representing parenchymal tissues, while barrier cells can be seeded within the lumens to represent the barrier tissues.

Mimicking cell-cell/organ-organ interactions.

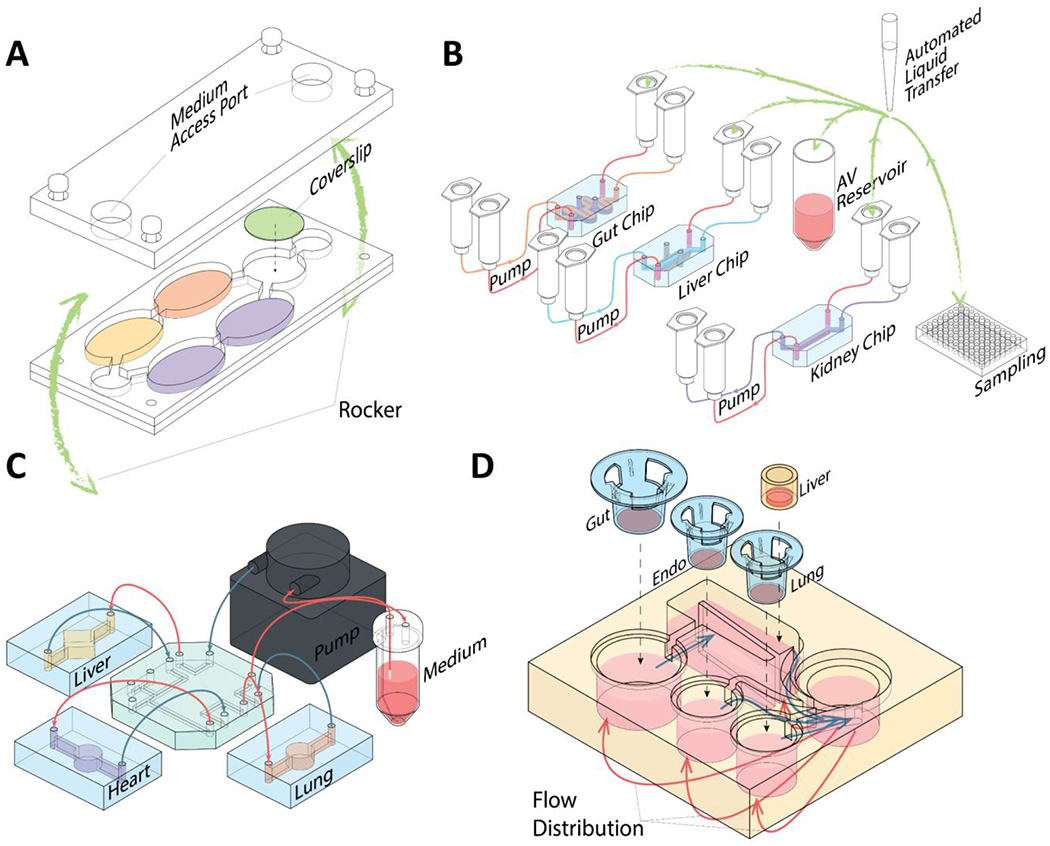

Finally, the prediction of PK/PD profiles, ADME properties, and drug-induced toxicity requires the consideration of cell-cell/organ-organ interactions. A simple way to mimic cell-cell interaction is the inclusion of diffusion channels (Fig. 4B). These diffusion channels are smaller than the cells, restricting the cells to their respective culture chambers but are sufficiently large to allow diffusion of smaller molecules, allowing cross-talk between chambers [72, 73], The greatest advantage of OoCs, however, is the ability to fluidically link multiple OoCs to mimic multi-organ physiology. Currently, multiple methods have been demonstrated to link multiple organs fluidically to reproduce organ-organ interactions. For example, Shuler and Hickman’s groups adopted the approach of integrating the multiple-organ chambers on a single platform where the medium is recirculated by using a rocker (Fig. 5A) [74, 75]. Ingber’s group opted to use an automated liquid transfer to pipette medium from one chip to another (Fig. 5B) [76]. We employed the use of fluidic tubing coupled to a pump linking multiple OoCs together (Fig. 5C) [77, 78]. Lastly, Griffith’s group in collaboration with Draper Laboratory designed an open-microfluidic platform with on-board pneumatic-driven pumps to control medium circulation across multiple Transwell® inserts (Fig. 5D) [62]. Qualitative and quantitative prediction of PK parameters, ADME profiles, and drug toxicity responses have been realized using these fluidically coupled OoC [10, 79, 80].

Figure 5.

A) Schematic representation of a pumpless, multi-organ system consisting of five culture chambers. Fluid circulation is driven by gravity, using a rocker. B) Schematic representation of the fluidic linkage between organ chips (gut, liver, and kidney) and arteriovenous (AV) reservoir using an automated liquid transfer robot. C) Schematic representation of a microengineered heart-lung-liver model that is fluidically linked using tubing coupled to a peristaltic pump. D) Schematic representation of the PhysioMimix™ OoC platform (CN Bio). Cells are cultured on Transwell® inserts that are loaded into the platform integrated with pneumatic pumps for recirculating flow distribution.

Current Status of OoCs

In the last 15 years , countless OoC platforms and organotypic models have been demonstrated to be better predictors of safety and toxicity than traditional methods [25, 81]. We highly recommend published reviews where they discuss in greater details, the progress and validation of the many existing OoCs in the context of safety and toxicity assessment [10, 32, 34, 82].

The advancement in this field has also led to the emergence of several companies; many are already in partnership with several large pharmaceutical companies [17]. Furthermore, regulatory agencies and research agencies such as the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Department of Defense (DoD) are proactively providing momentum in this field. Pharmaceutical industries have also established partnerships with government agencies, academic innovators, and startup companies to support the development of OoCs and facilitate a path for successful adoption [22, 83].

Recommendation for Future Steps

Despite the emergence of several OoC companies, OoCs are still in their infancy. However, if the imperative, as Caicedo et al. have pointed out, is not simply to develop academic proof-of-concept but the widespread adoption in the industry, more deliberations should be undertaken by the researchers in the field of OoCs [84]. To get there, we suggest several elements that researchers can consider:

Integration with the existing pipeline.

How easily can the OoC be integrated into the existing biotechnology infrastructure? For OoC platforms that are targeted for higher-throughput assessments, integration with the existing infrastructure may be important. The existing biotechnology infrastructure in the pharmaceutical industry is a long-standing establishment constituting many years of refinement and hefty financial investment. There would be significant operational and financial advantages to convince the pharmaceutical industry to opt for new technologies (i.e., OoCs) when that becomes a necessity [85], Bridging the academic-to-industry gap may be facilitated by designing OoC platforms that permit easy adaptation to the existing biotechnological infrastructure. To that end, some OoC platforms adopt workflows that are familiar to the existing pipeline, such as adopting the familiar well-plate configuration (e.g., Mimetas, Alveolix, CN Bio, and Draper), a format that is recognizable to biologists and technicians in industry laboratory. For instance, the Mimetas platform (Fig. 3C) is not merely designed with the well-plate configuration but also designed to be operated with pipetting, a familiar workflow in biology and related disciplines. Another method of integration may involve the use of automated liquid-handling robots that are already widely adopted in the pharmaceutical industry. Large pharmaceutical companies are already using these automated liquid-handling robots to rapidly screen thousands of drug compounds in 2D cellular assays. For example, the approach by Ingber’s group (Fig. 5B), where robotic liquid-handling robots were used as the mode of fluidically linking multiple OoCs, can take advantage of the existing liquid-handling infrastructure in the pharmaceutical industry. It should be noted that while a complete integration of OoCs with the existing infrastructure is ideal, it may not be the most practical or economical approach. To that end, intermediary organizations such as contract research organizations (CROs) or Tissue Chip Testing Centers (TCTCs)I may be a practicable approach in the broad context of integrating OoC into the drug development pipeline.

User experiences.

How will the end-user rate the OoC’s usability? Unlike the developers of the devices in academic laboratories, biologists and technicians in industry laboratories may not be interested in handling the cumbersome tubing and pumps found in many OoC setups. A platform that is cumbersome to operate may impact the level of adoption by the end-users and may become a barrier in translating these OoCs to the industry. Therefore, the development of OoCs should emphasize designing workflows that can enhance usability. One good example is the company Emulate (a company based on the platform developed by Ingber’s group) (Fig. 4A), where much emphasis is placed on developing supporting devices and workflows to improve usability. They accomplish this by designing modular pods to house individual chips to improve portability, and also an integrated culture module to automate the maintenance of multiple pods concurrently. Another example is CN Bio (a company based on the platform developed by Griffith’s group), which also developed a docking station that takes care of all the plumbing functions so that end-users do not need to handle the cumbersome tubing and pumps. Alternatively, platforms can eliminate the use of cumbersome tubing by opting for a pumpless configuration based on gravity-driven fluid control. Hesperos (a company based on the platform developed by Shuler and Hickman’s groups) (Fig. 5A) and Mimetas are examples of platforms that adopted this strategy.

Scalability.

How scalable is the OoC platform? To translate a specific OoC platform, it must be viable for scalability. In practice, pharmaceutical companies are required to screen hundreds to thousands of drug candidates (Fig. 1). Platforms that are fine for small-scale research in academic laboratories may not be easily scaled up for the requirements needed for pharmaceutical applications in the industry. OoC-developers should consider factors such as manufacturability. Not all platform designs are amenable for cost-effective, high(er)-throughput manufacturing. In general, the additional complexity in channel architecture will inadvertently affect manufacturability. Furthermore, manufacturability may be hindered by the choice of materials. For example, it may be favorable to avoid using PDMS due to its inherent ability to absorb small molecules [86], which can be circumvented by choosing thermoplastics [87, 88]. Unfortunately, not all chip designs can be effectively manufactured using thermoplastics unlike PDMS in academic research laboratories [89]. Additionally, OoC-developers should consider scalability from the viewpoint of the workflow. Ultimately, the platform is handled by a large number of biologists or technicians in industrial laboratories. Do the preparation, maintenance, and sampling of the OoCs consist of complicated procedures prone to experimental errors? Importantly, the key to scalability is the ability to ensure reproducibility and robustness, even when operated by different users who may have limited experiences with these devices. To ensure good scalability, the entire workflow should be viable for automation with minimal human intervention. To that end, platforms such as OrganoPlate® by Mimetas and PREDICT96 from Draper Laboratory aim to provide higher-throughput systems that are suitable for automation. Lastly, scalability also refers to the scaling of organ volumes and perfusion rates to maintain physiological relevance [82]. The ability to conveniently scale organ volumes and perfusion rates can be helpful to end-users.

Versatility.

Can the same chip design/workflow be repurposed for different organ models? Ideally, the same chip design should be amenable to the mimicry of various types of organs. While careful consideration on maintaining biological relevance is necessary, a versatile chip design/workflow ensures that the skills and techniques gained from the mastery of a particular OoC can be transferable to create other OoCs. A quick look at the various commercially available platforms such as Emulate, Nortis, and Mimetas, similar or identical chip designs are amenable for various cell types and configurations to mimic different organ functions. Another feature potentially useful to end-users is the ability to interconnect OoC from different manufacturers. OoC developers can consider platforms with standardized designs that are compatible with existing platforms or those produced by other developers.

Partnership with industry and regulatory agencies.

Importantly, translation to the industry will require understanding the end-users and carefully defining their needs (i.e., physiology, endpoints, key readouts). Caicedo et al. concluded in their letter that academic researchers should engage in thoughtful and meaningful partnerships with biologists and industry scientists [84]. In another opinion piece published in this same journal, Levin et al. also believe that the most advantageous approach to dealing with the complex nature of the academic and industry collaboration is for there to be early partnerships between the two [90]. To this end, it is encouraging to see initiatives like the NIH Tissue Chip ConsortiumII that is aimed at bringing together academic institutes and industry partners (e.g., GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, AstraZeneca) to determine the marketability and adoption of OoCs into the research community (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions Box.

What are the ways to consistently validate and characterize each organ-on-a-chip platform on its ability to recapitulate the physiology relevance?

How can we ensure the repeatability and reproducibility of organ-on-a-chips between batches especially when most of them rely on primary human cells that are susceptible to batch-to-batch variations?

How can organ-on-a-chip platforms fit into the existing pharmaceutical/biotechnology infrastructure?

Do existing organ-on-a-chip platforms have the capability to scale up to a level where pharmaceutical companies can meaningfully and practicably employ them?

How can we achieve wider adoption of organ-on-a-chips by academic researchers and industry?

Concluding remarks

The 2020 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic is another stark reminder that we need better predictors for drug safety and efficacy to accelerate the development of drugs from the first phase to the approval for the market. Several OoC platforms, including those from our group [91] and Ingber’s group [92] have demonstrated potential in assessing antiviral therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2. EmulateIII, MimetasIV, and CN BioV are companies that have already formed partnership with the industry to employ their platforms to test potential therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, cross-border partnerships between multiple agencies have also been formed to promote the adoption of OoC for SARS-CoV-2 research VI. Novel viral outbreaks can occur again in the future [93] and we hope these initiatives can pave the way in accelerating drug development that can potentially prevent a future pandemic of similar proportion.

More recently, the FDA rolled out the Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs (ISTAND) Pilot Program to support the development of Drug Developmental Tools (DDTs), including OoCs, that may be acceptable for regulatory use VII. The ISTAND initiative is exciting for the OoC research community as it has the potential of accelerating the industrial translation of OoCs for drug development and approval (see Outstanding Questions).

It is undeniable that OoCs have the potential to provide better predictive models that can benefit the drug development process. To further develop OoCs as the standard to accelerate the drug development process, the next step is gaining industry acceptance and adoption (see Outstanding Questions). Academic researchers could continue to provide momentum to innovate and develop better predictive OoC models. At the same time, academic researchers are also in a unique position to make specific design considerations that can help drive OoCs for better industry adoption. The long-lasting partnerships between academic researchers and industrial partners can widen OoC adoption and ultimately accelerate drug development by providing a more accurate predictor for safety and toxicity assessment.

Highlights.

Several organs-on-a-chip (OoC) have been shown to recapitulate human physiology and pathology and demonstrated to show similar or better predictive capability for drug evaluation than static cellular cultures and animal models for drug evaluations.

With the continued advances in the development of OoCs, researchers have emphasized the development of multi-organ platforms termed as “human-body-on-a-chip” by establishing physiologic flow between organs to produce organ–organ interactions which permits the analysis of inter-dependent pharmacokinetics (PK), PK/pharmacodynamics (PD) and toxicokinetics/toxicodynamics (TK/TD) relationships in vitro.

The advancement of OoCs has led to several organs-on-a-chip/multi-organ-on-a-chip startups/companies in the last decade.

Regulatory agencies have also launched initiatives to support the development of Drug Developmental Tools (DDTs) including OoCs that are aimed for regulatory use.

Acknowledgements

T.C. thanks Ministry of Education (MOE), Singapore, for awarding the President’s Graduate Fellowship. Y.C.T. acknowledges ARC Future Fellowship (FT180100157), ARC Discovery Project (DP200101658), and Queensland University of Technology (FT150100398). M.H. acknowledges Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 2 from Ministry of Education, Singapore (MOE2019-T2-2-192) and 2nd A*STAR-AMED Joint Grant (A19B9b0067). Y.S.Z. acknowledges the National Institutes of Health (R21EB025027, R00C201603, R01EB028143, UG3TR003274) and the National Science Foundation (CBET-EBMS-123859).

Glossary

- Adverse drug reaction (ADR)

the appreciably harmful or unpleasant reaction resulting from the administering of a drug

- Angiogenic sprouting

the sprouting of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones

- Biomimicry

the design and production of systems that are modeled on biological entities and processes

- Drug-induced toxicity

the degree to which a drug (or equivalent) can damage an organism

- Efficacy

the measure of the ability of the drug to treat the intended condition

- Extracellular matrix (ECM)

a complex molecular network of noncellular components that provides physical support and biochemical/biophysical cues for tissue development and homeostasis

- Human-body-on-a-chip

an in vitro multi-organ system aimed at recapitulating in vivo organ-organ crosstalk

- Idiosyncratic drug reaction

the unpredictable adverse effects that cannot be explained by the known mechanisms of action (i.e., pharmacology, safety, and toxicology)

- Metabolite

the intermediate or final product of a metabolic reaction catalyzed by an enzyme that naturally occurs within cells

- Parenchymal tissue

the tissue that is responsible for the function of a particular organ

- Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD)

the pharmacologic disciplines that study the effects of the body on the drug (PK) and the effects of the drug on the body (PD)

- Phenotype

the observable physical or biochemical characteristics of cells/tissue

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)

the strain of coronavirus that causes a respiratory illness responsible for the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

- Spheroid

a three-dimensional, usually spherical cellular aggregate

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relating to this work.

Resources

References

- [1].Batta A, Kalra BS, Khirasaria R, Trends in FDA drug approvals over last 2 decades: An observational study, Journal of family medicine and primary care, 9(2020) 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ridings JE, The thalidomide disaster, lessons from the past, Teratogenicity Testing, Springer 2013, pp. 575–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Loiodice S, Nogueira da Costa A, Atienzar F, Current trends in in silico, in vitro toxicology, and safety biomarkers in early drug development, Drug and chemical toxicology, 42(2019) 113–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Loman NJ, Misra RV, Dallman TJ, Constantinidou C, Gharbia SE, Wain J, et al. , Performance comparison of benchtop high-throughput sequencing platforms, Nat Biotechnol, 30(2012) 434–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Balijepalli A, Sivaramakrishan V, Organs-on-chips: research and commercial perspectives, Drug Discov Today, 22(2017) 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Deng J, Qu Y, Liu T, Jing B, Zhang X, Chen Z, et al. , Recent organ-on-a-chip advances toward drug toxicity testing, development, 19(2018) 20. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alteri E, Guizzaro L, Be open about drug failures to speed up research, Nature Publishing Group2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pound P, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Is it possible to overcome issues of external validity in preclinical animal research? Why most animal models are bound to fail, J Transl Med, 16(2018) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meigs L, Smirnova L, Rovida C, Leist M, Hartung T, Animal testing and its alternatives–The most important omics is economics, ALTEX-Alternatives to animal experimentation, 35(2018) 275–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ingber DE, Is it Time for Reviewer 3 to Request Human Organ Chip Experiments Instead of Animal Validation Studies?, Adv Sci, (2020) 2002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blow N, Microfluidics: in search of a killer application, Nat Methods, 4(2007) 665–70. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sackmann EK, Fulton AL, Beebe DJ, The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research, Nature, 507(2014) 181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ma C, Peng Y, Li H, Chen W, Organ-on-a-Chip: A New Paradigm for Drug Development, Trends Pharmacol Sci, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Picollet-D’hahan N, Zuchowska A, Lemeunier I, Le Gac S, Multiorgan-on-a-Chip: A Systemic Approach To Model and Decipher Inter-Organ Communication, Trends Biotechnol, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ingber DE, Reverse engineering human pathophysiology with organs-on-chips, Cell, 164(2016) 1105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ribas J, Zhang YS, Pitrez PR, Leijten J, Miscuglio M, Rouwkema J, et al. , Biomechanical strain exacerbates inflammation on a progeria-on-a-Chip model, Small, 13(2017) 1603737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang B, Radisic M, Organ-on-a-chip devices advance to market, Lab Chip, 17(2017) 2395–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Przekwas A, Somayaji MR, Computational pharmacokinetic modeling of organ-on-chip devices and microphysiological systems, Organ-on-a-chip, Elsevier2020, pp. 311–61. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Piñero J, Furlong LI, Sanz F, In silico models in drug development: where we are, Curr Opin Pharmacol, 42(2018) 111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Selick HE, Beresford AP, Tarbit MH, The emerging importance of predictive ADME simulation in drug discovery, Drug Discov Today, 7(2002) 109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sehnert SS, Drug Bioavailability: Estimation of solubility, permeability, absorption and bioavailability, J Natl Med Assoc, 96(2004) 1243. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ewart L, Dehne E-M, Fabre K, Gibbs S, Hickman J, Hornberg E, et al. , Application of microphysiological systems to enhance safety assessment in drug discovery, Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 58(2018) 65–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sung JH, Koo J, Shuler ML, Mimicking the Human Physiology with Microphysiological Systems (MPS), BioChip Journal, (2019) 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Guengerich FP, Mechanisms of drug toxicity and relevance to pharmaceutical development, Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, (2010) 1010210090-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang B, Korolj A, Lai BFL, Radisic M, Advances in organ-on-a-chip engineering, Nat Rev Mater, 3(2018) 257–78. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Viravaidya K, Sin A, Shuler ML, Development of a microscale cell culture analog to probe naphthalene toxicity, Biotechnol Prog, 20(2004) 316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sin A, Chin KC, Jamil MF, Kostov Y, Rao G, Shuler ML, The design and fabrication of three-chamber microscale cell culture analog devices with integrated dissolved oxygen sensors, Biotechnol Prog, 20(2004)338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, Ingber DE, Reconstituting Organ-Level Lung Functions on a Chip, Science, 328(2010) 1662–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dehne E-M, Hickman J, Shuler M, Biologically-inspired microphysiological systems, The History of Alternative Test Methods in Toxicology, Elsevier2019, pp. 279–85. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Huh D, Fujioka H, Tung Y-C, Futai N, Paine R, Grotberg JB, et al. , Acoustically detectable cellular-level lung injury induced by fluid mechanical stresses in microfluidic airway systems, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 104(2007) 18886–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shuler M, Ghanem A, Quick D, Wong M, Miller P, A self-regulating cell culture analog device to mimic animal and human toxicological responses, Biotechnol Bioeng, 52(1996) 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fowler S, Chen WLK, Duignan DB, Gupta A, Hariparsad N, Kenny JR, et al. , Microphysiological systems for ADME-related applications: current status and recommendations for system development and characterization, Lab Chip, 20(2020) 446–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dehne E-M, Marx U, Human body-on-a-chip systems, Organ-on-a-chip, Elsevier2020, pp. 429–39. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fabre K, Berridge B, Proctor WR, Ralston S, Will Y, Baran SW, et al. , Introduction to a manuscript series on the characterization and use of microphysiological systems (MPS) in pharmaceutical safety and ADME applications, Lab Chip, 20(2020) 1049–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ingber D, Mechanobiology and diseases of mechanotransduction, Ann Med, 35(2003) 564–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim L, Toh Y-C, Voldman J, Yu H, A practical guide to microfluidic perfusion culture of adherent mammalian cells, Lab Chip, 7(2007) 681–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vohrer U, Interfacial engineering of functional textiles for biomedical applications, Plasma technologies for textiles, (2007) 202. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ong LJY, Ching TTH, Chong LH, Arora S, Li H, Hashimoto M, et al. , Self-Aligning Tetris-Like (TILE) Modular Microfluidic Platform for Mimicking Multi-Organ Interactions, Lab Chip, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Toh Y-C, Zhang C, Zhang J, Khong YM, Chang S, Samper VD, et al. , A novel 3D mammalian cell perfusion-culture system in microfluidic channels, Lab Chip, 7(2007) 302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vulto P, Dame G, Maier U, Makohliso S, Podszun S, Zahn P, et al. , A microfluidic approach for high efficiency extraction of low molecular weight RNA, Lab Chip, 10(2010) 610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shin Y, Han S, Jeon JS, Yamamoto K, Zervantonakis IK, Sudo R, et al. , Microfluidic assay for simultaneous culture of multiple cell types on surfaces or within hydrogels, Nat Protoc, 7(2012) 1247–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jeon JS, Bersini S, Whisler JA, Chen MB, Dubini G, Charest JL, et al. , Generation of 3D functional microvascular networks with human mesenchymal stem cells in microfluidic systems, Integr Biol, 6(2014) 555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Moreno EL, Hachi S, Hemmer K, Trietsch SJ, Baumuratov AS, Hankemeier T, et al. , Differentiation of neuroepithelial stem cells into functional dopaminergic neurons in 3D microfluidic cell culture, Lab Chip, 15(2015) 2419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cao X, Ashfaq R, Cheng F, Maharjan S, Li J, Ying G, et al. , A tumor-on-a-chip system with bioprinted blood and lymphatic vessel pair, Adv Funct Mater, 29(2019) 1807173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Junaid A, Schoeman J, Yang W, Stam W, Mashaghi A, van Zonneveld AJ, et al. , Metabolic response of blood vessels to TNFα, Elife, 9(2020) e54754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].van Duinen V, Stam W, Borgdorff V, Reijerkerk A, Orlova V, Vulto P, et al. , Standardized and Scalable Assay to Study Perfused 3D Angiogenic Sprouting of iPSC-derived Endothelial Cells In Vitro, J Vis Exp, (2019) e59678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Osaki T, Sivathanu V, Kamm RD, Engineered 3D vascular and neuronal networks in a microfluidic platform, Sci Rep, 8(2018) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ingber DE, Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again, FASEB J, 20(2006) 811–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Stucki AO, Stucki JD, Hall SR, Felder M, Mermoud Y, Schmid RA, et al. , A lung-on-a-chip array with an integrated bio-inspired respiration mechanism, Lab Chip, 15(2015) 1302–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kim HJ, Li H, Collins JJ, Ingber DE, Contributions of microbiome and mechanical deformation to intestinal bacterial overgrowth and inflammation in a human gut-on-a-chip, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 113(2016) E7–E15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Herland A, Maoz BM, Das D, Somayaji MR, Prantil-Baun R, Novak R, et al. , Quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetic responses to drugs via fluidically coupled vascularized organ chips, Nat Biomed Eng, 4(2020) 421–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Even-Ram S, Yamada KM, Cell migration in 3D matrix, Curr Opin Cell Biol, 17(2005) 524–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Feder-Mengus C, Ghosh S, Reschner A, Martin I, Spagnoli GC, New dimensions in tumor immunology: what does 3D culture reveal?, Trends Mol Med, 14(2008) 333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Liu H, Wang Y, Cui K, Guo Y, Zhang X, Qin J, Advances in Hydrogels in Organoids and Organs-on-a-Chip, Adv Mater, 31(2019) 1902042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Terrell JA, Jones CG, Kabandana GKM, Chen C, From Cells-on-a-chip to Organs-on-a-chip: Scaffolding Materials for 3D Cell Culture in Microfluidics, J Mater Chem B, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jeon JS, Bersini S, Gilardi M, Dubini G, Charest JL, Moretti M, et al. , Human 3D vascularized organotypic microfluidic assays to study breast cancer cell extravasation, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 112(2015)214–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Poussin C, Kramer B, Lanz HL, Van den Heuvel A, Laurent A, Olivier T, et al. , 3D human microvessel-on-a-chip model for studying monocyte-to-endothelium adhesion under flow–application in systems toxicology, ALTEX-Alternatives to animal experimentation, 37(2020) 47–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Huh D, Kim HJ, Fraser JP, Shea DE, Khan M, Bahinski A, et al. , Microfabrication of human organs-on-chips, Nat Protoc, 8(2013) 2135–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Novak R, Didier M, Calamari E, Ng CF, Choe Y, Clauson SL, et al. , Scalable fabrication of stretchable, dual channel, microfluidic organ chips, J Vis Exp, (2018) e58151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Chen WL, Edington C, Suter E, Yu J, Velazquez JJ, Velazquez JG, et al. , Integrated gut/liver microphysiological systems elucidates inflammatory inter-tissue crosstalk, Biotechnol Bioeng, 114(2017) 2648–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Sakolish CM, Esch MB, Hickman JJ, Shuler ML, Mahler GJ, Modeling barrier tissues in vitro: methods, achievements, and challenges, EBioMedicine, 5(2016) 30–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Edington CD, Chen WLK, Geishecker E, Kassis T, Soenksen LR, Bhushan BM, et al. , Interconnected microphysiological systems for quantitative biology and pharmacology studies, Sci Rep, 8(2018) 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rowe C, Shaeri M, Large E, Cornforth T, Robinson A, Kostrzewski T, et al. , Perfused human hepatocyte microtissues identify reactive metabolite-forming and mitochondria-perturbing hepatotoxins, Toxicol In Vitro, 46(2018) 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sarkar U, Ravindra KC, Large E, Young CL, Rivera-Burgos D, Yu J, et al. , Integrated assessment of diclofenac biotransformation, pharmacokinetics, and omics-based toxicity in a three-dimensional human liver-immunocompetent coculture system, Drug Metab Dispos, 45(2017) 855–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Schimek K, Frentzel S, Luettich K, Bovard D, Rütschle I, Boden L, et al. , Human multi-organ chip co-culture of bronchial lung culture and liver spheroids for substance exposure studies, Sci Rep, 10(2020) 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Weber EJ, Chapron A, Chapron BD, Voellinger JL, Lidberg KA, Yeung CK, et al. , Development of a microphysiological model of human kidney proximal tubule function, Kidney int, 90(2016) 627–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Homan KA, Kolesky DB, Skylar-Scott MA, Herrmann J, Obuobi H, Moisan A, et al. , Bioprinting of 3D convoluted renal proximal tubules on perfusable chips, Sci Rep, 6(2016) 34845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lin NY, Homan KA, Robinson SS, Kolesky DB, Duarte N, Moisan A, et al. , Renal reabsorption in 3D vascularized proximal tubule models, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 116(2019) 5399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kolesky DB, Homan KA, Skylar-Scott MA, Lewis JA, Three-dimensional bioprinting of thick vascularized tissues, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 113(2016) 3179–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Trietsch SJ, Naumovska E, Kurek D, Setyawati MC, Vormann MK, Wilschut KJ, et al. , Membrane-free culture and real-time barrier integrity assessment of perfused intestinal epithelium tubes, Nat Commun, 8(2017) 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Gijzen L, Yengej FAY, Schutgens F, Vormann MK, Ammerlaan CM, Nicolas A, et al. , Culture and analysis of kidney tubuloids and perfused tubuloid cells-on-a-chip, Nat Protoc, (2021) 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Chong LH, Li H, Wetzel I, Cho H, Toh Y-C, A liver-immune coculture array for predicting systemic drug-induced skin sensitization, Lab Chip, 18(2018) 3239–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Terrell-Hall TB, Ammer AG, Griffith JI, Lockman PR, Permeability across a novel microfluidic blood-tumor barrier model, Fluids Barriers CNS, 14(2017) 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Oleaga C, Bernabini C, Smith AS, Srinivasan B, Jackson M, McLamb W, et al. , Multi-organ toxicity demonstration in a functional human in vitro system composed of four organs, Sci Rep, 6(2016) 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].McAleer CW, Long CJ, Elbrecht D, Sasserath T, Bridges LR, Rumsey JW, et al. , Multi-organ system for the evaluation of efficacy and off-target toxicity of anticancer therapeutics, Sci Transl Med, 11(2019) eaav1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Novak R, Ingram M, Marquez S, Das D, Delahanty A, Herland A, et al. , Robotic fluidic coupling and interrogation of multiple vascularized organ chips, Nat Biomed Eng, (2020) 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Zhang YS, Aleman J, Shin SR, Kilic T, Kim D, Shaegh SAM, et al. , Multisensor-integrated organs-on-chips platform for automated and continual in situ monitoring of organoid behaviors, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 114(2017) E2293–E302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Skardal A, Murphy SV, Devarasetty M, Mead I, Kang H-W, Seol Y-J, et al. , Multi-tissue interactions in an integrated three-tissue organ-on-a-chip platform, Sci Rep, 7(2017) 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Shuler ML, Advances in organ-, body-, and disease-on-a-chip systems, Lab Chip, 19(2019) 9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Low LA, Mummery C, Berridge BR, Austin CP, Tagle DA, Organs-on-chips: Into the next decade, Nat Rev Drug Discov, (2020) 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bhatia SN, Ingber DE, Microfluidic organs-on-chips, Nat Biotechnol, 32(2014) 760–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wang YI, Carmona C, Hickman JJ, Shuler ML, Multiorgan microphysiological systems for drug development: strategies, advances, and challenges, Adv Healthc Mater, 7(2018) 1701000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ewart L, Fabre K, Chakilam A, Dragan Y, Duignan DB, Eswaraka J, et al. , Navigating tissue chips from development to dissemination: A pharmaceutical industry perspective, Exp Biol Med, 242(2017) 1579–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Caicedo HH, Brady ST, Microfluidics: the challenge is to bridge the gap instead of looking for a ‘killer app’, Trends Biotechnol, 34(2016) 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Volpatti LR, Yetisen AK, Commercialization of microfluidic devices, Trends Biotechnol, 32(2014) 347–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Van Meer B, de Vries H, Firth K, van Weerd J, Tertoolen L, Karperien H, et al. , Small molecule absorption by PDMS in the context of drug response bioassays, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 482(2017)323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Pourmand A, Shaegh SAM, Ghavifekr HB, Aghdam EN, Dokmeci MR, Khademhosseini A, et al. , Fabrication of whole-thermoplastic normally closed microvalve, micro check valve, and micropump, Sens Actuators B Chem, 262(2018) 625–36. [Google Scholar]

- [88].Shaegh SAM, Pourmand A, Nabavinia M, Avci H, Tamayol A, Mostafalu P, et al. , Rapid prototyping of whole-thermoplastic microfluidics with built-in microvalves using laser ablation and thermal fusion bonding, Sens Actuators B Chem, 255(2018) 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kurth F, Györvary E, Heub S, Fedroit D, Paoletti S, Renggli K, et al. , Organs-on-a-chip engineering, Organ-on-a-chip, Elsevier2020, pp. 47–130. [Google Scholar]

- [90].Fevin FA, Behar-Cohen F, The Academic–Industrial Complexity: Failure to Launch, Trends Pharmacol Sci, 38(2017) 1052–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Huang D, Liu T, Liao J, Maharjan S, Xie X, Pérez M, et al. , Reversed-engineered human alveolar lung-on-a-chip model, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 118(2021) e2016146118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Si L, Bai H, Rodas M, Cao W, Oh CY, Jiang A, et al. , A human-airway-on-a-chip for the rapid identification of candidate antiviral therapeutics and prophylactics, Nat Biomed Eng, (2021). 10.1038/s41551-021-00718-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Graham BS, Corbett KS, Prototype pathogen approach for pandemic preparedness: world on fire, J Clin Investig, 130(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]