Abstract

Sinonasal inverted papilloma (SNIP), Inverting papilloma, Schneiderian papilloma etc. It is a benign tumor with incidence nearly 70% of all sinonasal papilloma and 0.5–4.0% of all sinonasal neoplasms. The most common site of origin is lateral nasal wall and common presenting symptom is nasal obstruction followed by epistaxis. On histopathology examination, it is characterized by invagination of neoplastic epithelium into underlying stroma. With the advent of technology, the endoscopic modified dankers approach became the surgical approach of choice. The present study was undertaken to study its role in management of SNIP with reference to rate of recurrence and malignancy. An observational study was conducted in a tertiary health center in which 40 biopsy proven cases of SNIP, operated by endoscopic assisted modified Danker’s approach between September 2008 and January 2019 with minimum follow-up period of 6 months were analyzed. Male:Female ratio was 2.33:1. The most common symptom was nasal obstruction (97.5%) followed by rhinorrhoea (87.5%). Using various imaging and diagnostic measures, lateral nasal wall was found to be the most common site of origin. Out of total 40 cases, 9 (27.5%) patients had recurrence, of these, 6 were benign and remaining 3 had malignancy as confirmed by biopsy. Most of the cases of SNIP can be managed endoscopically, although extensive lesions or the lesions with malignant transformation, external approach may be needed so expertise in both endoscopic and conventional techniques is needed. Although most of the recurrences occurred in first 2 years, but life time follow-up is advisable.

Keywords: Inverted papilloma, Modified Danker’s, SNIP, Krouse staging, Microdebrider

Introduction

Sinonasal Inverted papilloma (SNIP) is a benign tumor of epithelial origin of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses having variable biological behavior was first described by Ward and Billroth in 1854. It arises from ectodermal schneiderian membrane. Its incidence is about 70% of all sinonasal papillomas and 0.5–4.0% of all neoplasms of sinonasal tract [1, 2].

Commonly it arises from lateral nasal wall with extension to paranasal sinuses and may extend to the orbit or intracranial cavity [3, 4]. There is a male predominance. Age group of 40–70 years are more commonly affected [2].

Unilateral nasal obstruction is the most common presenting symptom followed by epistaxis, rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, feeling of pressure and headache. Grossly, its appearance is bulky, firm and granular polyp. Inverted papilloma (IP) are staged using Krouse system, where T1-Confined to nasal cavity; T2-Osteomeatal complex region, ethmoids, or medial maxillary involvement (with and without nasal cavity involvement); T3-Any wall of maxillary sinus but medial, frontal sinus or sphenoid with or without T2 criteria and T4-Any extra sinus involvement or malignancy [5].

On Histopathology, it is characterized by invagination of neoplastic epithelium into underlying stroma [6]. Being benign in nature it does not invade the underlying bone, but the surface border between inverted papilloma and bone is pathological and irregular with cervices and variable inflammatory changes. This may lead to mucosal tissue being embedded within these bony crevices, which could become a potential area of tumor recurrence. The recurrence rate is very wide between 0 to 78% that too within 2 years of surgical intervention [7, 8]. Synchronous malignancies accounts for 7.1% and metachronous malignancies account for 3.6% cases [9].

Earlier, lateral rhinotomy with medial maxillectomy was the surgery of choice with acceptable rates of recurrence. But this led to cosmetic disfigurement due to facial incision, increased morbidity and chronic crusting due to permanent alteration of normal sinonasal physiology. With the advent of technology, use of Computerized tomography (CT) scans and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of para nasal sinuses (PNS), there has been a revolution in the management of sinonasal papillomas with the use of endoscopic technique. Although similar cure rate and recurrence rates have been reported by many authors as with that of external approach.

The present study was undertaken to analyze the results of endoscopic approach and to analyze out the advantages of endoscopic Modified Dankers approach to SNIP with special reference to malignant transformations, and recurrence rates. Pre-operative diagnostic work-up, management strategy, follw-up and surgical outcome will also be discussed.

Methodology

The present study is an observational design, conducted at the department of otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery in a tertiary care center. All biopsy proven cases of sinonasal inverted papilloma operated during the period from September 2008 to January 2019 were analyzed. Retrospectively cases from September 2008 to November 2016 were analyzed and prospective cases operated between December 2016 to January 2019 were analyzed.

A total 43 patients with Sino-nasal inverted papilloma, presenting or presented during the study period, of these 3 patients were lost to follow-up, hence the final analysis was carried out on 40 patients.

It was initiated after obtaining permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee of our institution.

Inclusion criteria for retrospective cases was, biopsy proven sinonasal inverted papilloma already operated by endoscopic approach were included and consent was obtained on telephone for their participation in the study.

Inclusion criteria for prospective cases was availability of biopsy report confirming sinonasal inverted papilloma for cases which had undergone surgery by endoscopic modified Danker’s approach during the study period and were willing to provide their voluntary written informed consent for participation in the study, and for undergoing endoscopic surgery. Patients with recurrence and malignant transformation of inverted papilloma willing to participate in the study were also included. Patients giving negative consent for participation and the patients unfit for surgery were excluded from the study.

Included patients had a preoperative diagnostic nasal endoscopy, CT scan or MRI of paranasal sinuses with histopathological diagnosis of inverted papilloma.

The study was explained to the patients and/or his/her legally acceptable representative in detail in their own language. After obtaining a voluntary written informed consent, the study procedures were initiated.

Data collected included patient demographic, radiographic, histopathology, and intra-operative findings and complications in terms of recurrence and malignant transformation. Patients were followed-up for a minimum period of 6 months with further advising of life time follow-up.

Surgical Planning and Procedure

Preoperatively nose was prepared with gauze soaked in 4% lignocaine with adrenaline in 1:1,00000 dilution and nasal mucosa infiltrated with lignocaine 2% with 1:100000 dilution. Surgical procedure was performed under general anesthesia. Endoscopes used were 4 mm rigid nasal endoscopes with various angulations as per requirement—0°, 30°, 45°, 70°.

Modified Danker’s Approach

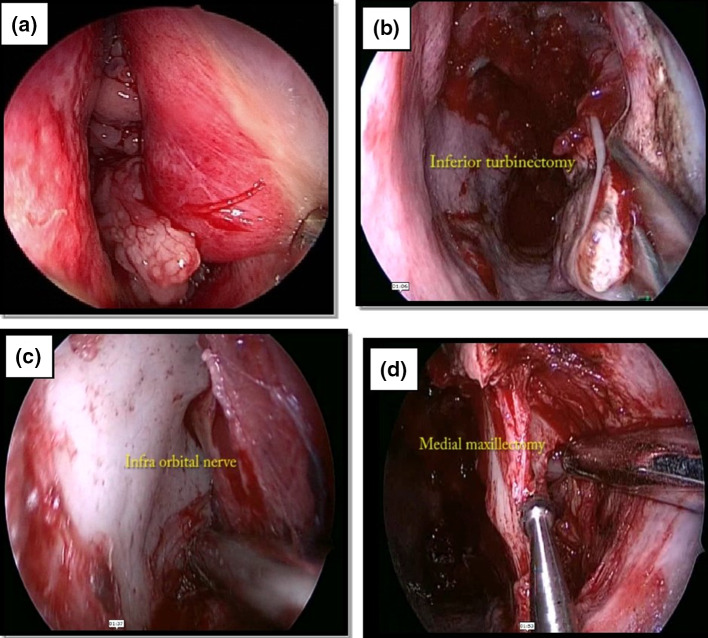

Under endoscopic guidance, tumor bulk was reduced using electrocauterization forceps or microdebrider to obtain material for histopathology examination and visualize available anatomical landmarks better and identify the tumor base.

The inferior turbinate was cauterized, cut and removed. An incision was made along the pyriform crest, followed by removal of inferior part of pyriform crest creating an entrance to the maxillary sinus using a diamond drill. This approach was further enlarged by cutting the bone at antero-medial wall of maxillary sinus. Preservation of infra-orbital nerve was ensured [Figure 1]. The tumor was excised by microdebrider or by using bipolar electroquaterization under adequate exposure. If the tumor arose from turbinate then enbloc resection of tumor along with turbinate was performed. Ethmoidectomy was done if the base involved the ethmoid sinuses. Resection followed by dacrocystorhinostomy was done in patients where tumor was too close to the nasolacrimal duct. Anterior sphenoidectomy with tumor excision was done in patients where tumor involved anterior wall of sphenoid sinus and frontal recess clearance was used to resect tumor in case of frontal sinus.

Fig. 1.

a Mulberry like appearance of Inverted pappiloma on Endoscopy. b Inferior Turbinectomy being done to create excess. c Identification and preservation of Infra-orbital nerve. d Anteromedial maxillectomy

The residual bone underlying the site of origin was polished with a diamond burr to remove microscopic mucosal remnant. Excised/resected specimen were sent for histopathological analysis.

The patients were discharged after being stabilized and in case of any malignancy, patients were also referred to the department of Radiation oncology for further management.

Follow-up

In the first year, patient had come for first follow-up after 1 week of surgery, then after 2 weeks, then after 1 month and then after 3 months. If no recurrence was seen, patient was advised to follow-up at 6 months and then on a yearly basis. Life time follow-up was advised to all the patients.

At each follow-up postoperatively, patient was examined for any residual disease using diagnostic nasal endoscopy and/or CT scan PNS. In case of suspicious lesion, biopsy was taken and histopathology examination was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

On the case to case basis, patients with recurrence were treated either endoscopically or by external approach.

All the patients were advised to come for regular follow-up throughout their life-time in spite of their histopathological status.

A customized proforma was designed for the purpose of the study. There was no additional financial burden on the patient and/or his/her legally acceptable representative. All the study related expenses were borne by the investigator. This study was not funded by any pharmaceutical company or any institution.

The data was presented in the form of tables and graphs.

Observation and Results

A total 40 biopsy proven cases of sinonasal inverted papilloma with minimum follow-up duration of 6 months were analyzed. There was a male preponderance in our study (28 males vs. 12 females) with a male: female ratio of 2.33: 1 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Gender distribution, Symptomatology, Site of orgin and Krouse staging of patients (n = 40)

| Gender | Frequency (n = 40) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 28 | 70 |

| Female | 12 | 30 |

| Male:Female Ratio | 2.33:1 | |

| Symptoms | ||

| Rhinorrhoea | 35 | 87.5 |

| Headache | 13 | 32.5 |

| Epistaxis | 9 | 22.5 |

| Nasal Obstruction | 39 | 97.5 |

| Site of origin | ||

| Nasal Cavity | 3 | 7.5 |

| Ethmoid air cells | 10 | 25 |

| Nasoethmoid | 4 | 10 |

| Maxillary sinus | 12 | 30 |

| Maxilloethmoid | 8 | 20 |

| Frontoethmoid | 3 | 7.5 |

| Krouse Staging | ||

| T1 | 3 | 7.5 |

| T2 | 15 | 37.5 |

| T3 | 19 | 47.5 |

| T4 | 3 | 7.5 |

The mean age was 54.5 ± 11.16 years with an age range of 14–65 years. There were 2 cases of bilateral (5.0%), 17 cases of left (42.5%) and 21 cases of right (52.5%) side involved.

Nasal obstruction was the commonest presenting symptom seen in all the patients (97.5%), followed by rhinorrhea (87.5%), headache (32.5%) and epistaxis (22.5%) [Table 1].

Based on radiological studies and nasal endoscopy, the site of tumor origin was noted. 3 (7.5%) tumors were from nasal cavity, 10 (25.0%) tumors were from ethmoids, 4 (10.0%) tumors from nasoethmoids, 12 (30.0%) tumors from maxillary, 8 (20.0%) from maxilloethmoids and 3 (7.5%) tumors from frontoethmoids [Table 1].

According to Krouse’s staging system, the patients were classified as T1 in 3 cases (7.5%), T2 in 15 cases (37.5%), T3 in 19 cases (47.5%) and T4 in 3 cases (7.5%) [Table 1].

Recurrence of inverted papilloma was seen in 9 (22.5%) patients after primary endoscopic resection. The duration of recurrence/malignancy from primary surgery was 19.87 ± 8.54 months [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients experiencing recurrence

| Patient | Primary surgery | Krouse stage | Site of origin | Recurrence duration (in Months) | Revision surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Endoscopic | T3 | Maxillary Sinus | 19 | Endoscopic |

| 2 | Endoscopic | T2 | Ethmoid air cells | 9 | Endoscopic |

| 3 | Endoscopic | T4 | Nasoethmoid | 24 | Endoscopic |

| 4 | Endoscopic | T3 | Maxillary sinus | 13 | Endoscopic |

| 5 | Endoscopic | T4 | Maxilloethmoid | 15 | Endoscopic |

| 6 | Endoscopic | T3 | Frontoethmoid | 37 | Endoscopic + external |

| 7 | Endoscopic | T4 | Nasoethmoid | 19 | External (total maxillectomy) |

| 8 | Endoscopic | T3 | Maxillay sinus | 23 | External (total maxillectomy) |

| 9 | Endoscopic | T3 | Maxilloethmoid | 11 | External (total maxillectomy) |

Of these 40, recurrence was seen in 9 patients of which in 8 patients’ it was seen in nasal, ethmoid, nasothemoids, maxillary and maxilloethmoid group and in 1 patient it was seen in frontoethmoid group. Of the 8 patients, 5 patients were managed by endoscopic re-resection and 3 patients were confirmed squamous cell carcinoma on biopsy of lesion during recurrence, so total maxillectomy was performed. 1 patient of frontoethmoidal group was managed with external approach [Table 2].

After secondary/revision surgery, none of the patients showed any recurrence/malignancy at the next 6 months follow-up, but were advised for life-time follow-up.

42.7% of the patients had origin from nasal, ethmoids or nasoethmoid, which were also primarily managed with endoscopic approach. Of them, 3 (17.64%) patients had recurrence. All recurrences were at the previously resected, original site of origin. Of these 3 patients, 2 patients underwent endoscopic re-resection, while 1 patient underwent total maxillectomy, with ethmoidectomy because of proven malignancy, this surgery was performed by external approach [Table 2].

Maxillary and maxilloethmoid tumor accounted for 50% of the total patients. All these patients underwent endoscopic resection of tumor. Recurrence was seen in 5 (25.0%) patients. The recurrence was seen at the previously resected, original site of origin here as well. 3 patients underwent endoscopic re-resection, while 2 patients underwent total maxillectomy (proven malignant).

Frontoethmoidal tumors accounted for 3 (7.5%) of the total patients and endoscopic resection was done in all these patients. Recurrence was seen in only 1 (33.3%) patient, which was managed by external approach as the inferior table of the frontal sinus was eroded.

Malignancy was seen in 3 cases during recurrence, of which 2 were in Krouse Stage T3 and rest 1 was in Stage T4. These malignancies developed in maxillary sinus and all were diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma on histopathology. Post total maxillectomy they were further referred to department of radiation oncology for adjuvant treatment.

Discussion

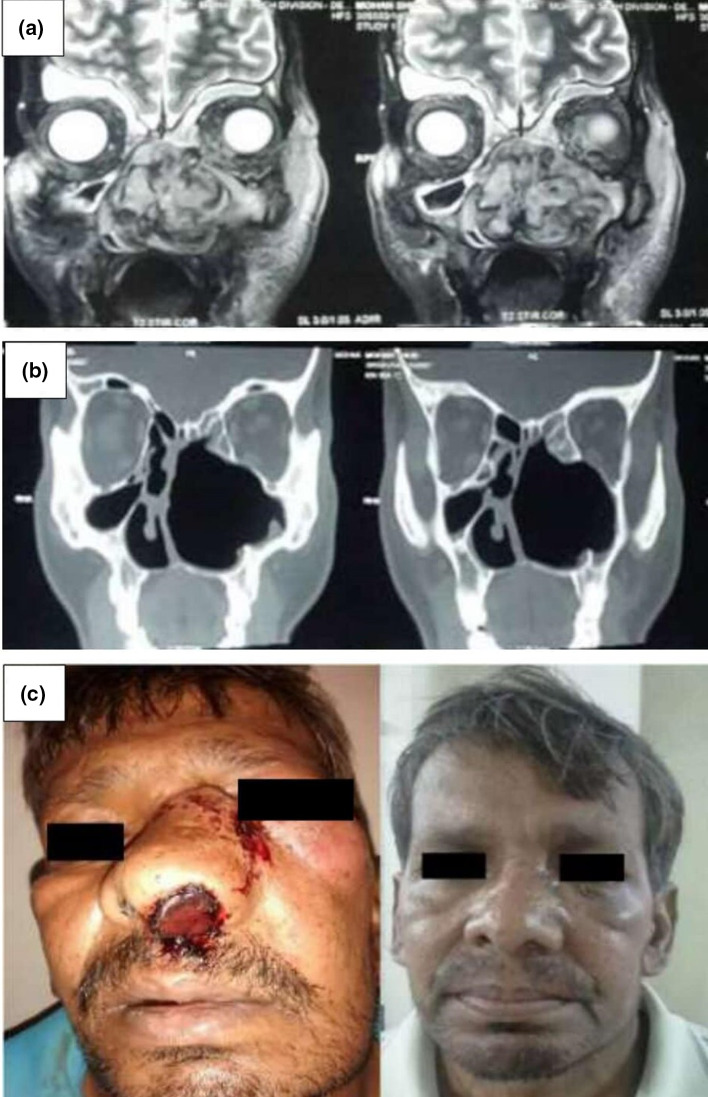

In last two decades a number of studies were presented and published which validate the efficacy of endoscopic approaches in obtaining optimal disease control and reasonable morbidity [10–13]. Male predominance is reported by various authors which is comparable to our observation with male to female ratio of 2:1 to 3:1 [14]. Lee et al, Sham et al. had reported a lower male predilection (2:1) than our study where the nasal obstruction was the commonest presenting symptom, followed by rhinorrhea, headache and epistaxis. Study done by deSouza et al. also reported similar findings, wherein they reported nasal blockage in 92.3%, rhinorrhea in 46.1% and epistaxis in 7.7% patients [15–17]. The prevalence of epistaxis was higher in study in comparison to deSouza et al. study. Most common site of origin was lateral nasal wall and least common was nasal septum which is consistent with literature, Kamel et al. characterized and illustrated that inverted papillomas involving the maxillary sinus in association with the lateral nasal wall originate from the maxillary sinus from its medial wall, fill the antrum, and then extend medially to the nasal cavity [18]. Lund suggested that “the term ‘recurrence’ merely indicates residual disease in majority of cases and is directly related to surgical approach and care with which IP is removed” [19]. So, it’s not wrong if it is said that inability to achieve complete resection is attributed to recurrence and not the tumor characteristic itself. A number of authors have supported the same [20]. With the advancement in imaging techniques and availability of multiplanar reconstruction, endoscope assisted surgery can be strategically planned preoperatively. Sham et al. in the year 2008 reported 100% positive predictive value of evidence of hyperostosis or bony strut in CT scan of PNS to identify the site of attachment or the possible site of origin of SNIP [21–23] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

NCCT of PNS a axial section b coronal section, showing hyperostosis and site of origin (arrow)

However, MRI gives better information and differentiation of SNIP from retained secretions and identification of probable malignant changes. On MRI the association of columnar appearance with bone remodeling differentiate SNIPs from malignant tumours [24].

Budu et al. in a case series of 162 cases over 15 years reported that most common stage according to Krouse’s classification was Stage III, with 105 cases (64.81%), followed by Stage II in 36 cases (22.22%). The least frequent were tumors in Stage I, accounting for 21 cases (12.96%) [25]. These results were comparable with our series as well.

In this study, all the primary cases where treated by endoscopic approach irrespective of its stage and extension. Medial maxillectomy (by modified Danker’s) with anterior–posterior ethmoidectomy, anterior sphenoidotomy were done as per the extension [26] The key to the success is locating the specific site of tumor origin or attachment, determining its extension, and completely removing the disease [27]. Budu et al. [25], most cases, staged as Stage III Krouse, were treated by endoscopic surgery by medial maxillectomy and at times followed by anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy. Ideally, release of the tumor implantation point is subperiosteal, followed by reaming of the underlying bone [16, 17]. Studies have also compared the endoscopic approach with external approach and found that operative parameters like operative time, estimated blood loss were comparable and hospital stay was shorter in the endoscopic group [28].

When consideration is given to the endoscopic resection of SNIP, the advantage and drawback of the approach must be weighed carefully. The endoscopic approach offers various advantages like brilliant illumination and magnification, thus allowing precise tumor resection and avoids damage to nearby uninvolved structure. The added advantages are no facial incision (Fig. 3), decreased morbidity, crusting, postoperative pain, bleeding and health care cost.

Fig. 3.

a Pre-operative MRI of PNS coronal section. b Post-operative CT scan of PNS, complete clearance of disease achieved. c Pre-operative and post-operative photographs of one of our patients. Dramatic aesthetic outcome achieved

Exposure to the frontal and sphenoid sinuses and orbital apex is improved.

The drawbacks must also be considered. Greater endoscopic expertise is required in surgeons’ hand and must be done by surgeons with considerable experience. Cost of endoscopic set up is also very high. Another important limitation of the endoscopic approach is difficulty in clearing disease from lateral part of frontal sinus and antero-lateral wall of maxillary sinus for such cases the procedure can be clubbed with Cald-well Lucs approach. In a study of 86 patients by Gras-Cabrerizo et al. 56 (66%) patients were treated with endoscopic excision 72%, complemented with a Caldwell-Luc procedure giving excellent result [29].

With follow up period being 6 months as minimum in this study, recurrence was seen in 9 (22.5%) of study cases and mean follow-up period was nearly 20 months. Sham et al. published a detailed data of time to recurrences of a group of 56 patients, which supported that statement that most recurrence occurred in 1st 2 years but there is no upper limit of time to recurrence [20]. The recurrence rate observed in our study was nearly 22% which is comparable to the studies by various authors although on a larger sample size [30–32]. All the recurrences in this series were observed at the site of primary lesion; also, the primary surgery was endoscopic modified Danker’s approach with necessary modifications. Based on site of origin, recurrence rate was statistically not significant and this can be attributed to the limited sample size of our study.

Conclusion

Endoscopic assisted Danker’s approach with modifications is the first-choice treatment of sinonasal inverted papillomas, owing to multi-angled magnified view of the surgical field. With the advancement in imaging techniques, a better preoperative planning is possible with possibility of locating site of origin. With the availability of powered instrumentation morbidity and rate of recurrence is also bought down dramatically. In our opinion, most of the cases of SNIP can be managed endoscopically at tertiary care centers, although extensive lesions or those with malignant transformation, external approach may be needed so expertise in both endoscopic and conventional techniques is needed. Although most of the recurrences occurred in first 2 years, life time follow-up is advisable to all the patients.

Acknowledgements

We heart fully thank all the faculty members of department of ENT, department of radiodiagnosis, department of anesthesiology and department of pathology for their valuable support.

Funding

There was no funding for this work.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors mentioned in this study declare a no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from every individual participant included in the study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with clinical standards of institutional and national research committee. Prior approval was taken from institutional approval committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ward N. A mirror of the practice of medicine and surgery in the hospitals of London: London hospital. Lancet. 1854;2:480–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)54853-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawson W, Kaufman MR, Biller HF. Treatment outcomes in the management of inverted papilloma: an analysis of 160 cases. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(9):1548–1556. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200309000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vrabec DP. The inverted Schneiderian papilloma: a 25-year study. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:582–605. doi: 10.1002/lary.5541040513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melroy CT, Senior BA. Benign sinonasal neoplasms: a focus on inverting papilloma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2006;39(3):601–617. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krouse JH. Development of a staging system for inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(6):965–968. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200006000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyams VJ. Papillomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. A clinicopathological study of 315 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1971;80(2):192–206. doi: 10.1177/000348947108000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calcaterra TC, Thompson JW, Paglia DE. Inverting papillomas of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(1):53–60. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers EN, Schramm VL, Jr, Barnes EL., Jr Management of inverted papilloma of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1981;91(12):2071–2084. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198112000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JY, Yoon JK, Citardi MJ, Batra PS, Roh HJ. The prevalence of human papilloma virus infection in sinonasal inverted papilloma specimens classified by histological grade. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(6):664–669. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawson W, Patel ZM. The evolution of management for inverted papilloma: an analysis of 200 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:330–335. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reh DD, Lane AP. The role of endoscopic sinus surgery in the management of sinonasal inverted papilloma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:6–10. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32831b9cd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sautter NB, Cannady SB, Citardi MJ, Roh HJ, Batra PS. Comparison of open versus endoscopic resection of inverted papilloma. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:320–323. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busquets JM, Hwang PH. Endoscopic resection of sinonasal inverted papilloma: a meta analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawson W, Le Benger J, Som P, Bernard PJ, Biller HF. Inverted papilloma: an analysis of 87 cases. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(11):1117–1124. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee TJ, Huang SF, Huang CC. Tailored endoscopic surgery for the treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma. Head Neck. 2004;26(2):145–153. doi: 10.1002/hed.10350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sham CL, Woo JK, van Hasselt CA, Tong MC. Treatment results of sinonasal inverted papilloma: an 18-year study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23(2):203–211. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sousa AM, Vicenti AB, Speck Filho J, Cahali MB. Retrospective analysis of 26 cases of inverted nasal papillomas. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;78(1):26–30. doi: 10.1590/s1808-86942012000100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamel RH. Transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy in inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:847–853. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund VJ. Optimum management of inverted papilloma. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:194–197. doi: 10.1258/0022215001905319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lund V, Stammberger H, Nicolai P, et al. European position paper on endoscopic management of tumours of the nose, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Rhinology. 2010;22:1–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sham CL, King AD, van Hasselt A, Tong MC. The roles and limitations of computed tomography in the preoperative assessment of sinonasal inverted papillomas. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:144–150. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhalla RK, Wright ED. Predicting the site of attachment of sinonasal inverted papilloma. Rhinology. 2009;47:345–348. doi: 10.4193/Rhin08.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousuf K, Wright ED. Site of attachment of inverted papilloma predicted by CT findings of osteitis. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:32–36. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maroldi R, Farina D, Palvarini L, Lombardi D, Tomenzoli D, Nicolai P. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of inverted papilloma: differential diagnosis with malignant sinonasal tumors. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:305–310. doi: 10.1177/194589240401800508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Budu V, Schnaider A, Bulescu I. Endoscopic approach of sinonasal inverted papilloma—our 15 years’ experience on 162 cases. Rom J Rhinol. 2015;5(17):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waitz G, Wigand ME. Result of endoscopic sinus surgey for treatment of inverted papillomas. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:917–921. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199208000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han JK, Smith TL, Loherl T, Toohil RJ, Smith MM, et al. An evolution in the management of sinonasal inverting papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1395–1400. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sautter NB, Cannady SB, Citardi MJ, Roh HJ, Batra PS. Comparison of open versus endoscopic resection of inverted papilloma. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(3):320–323. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gras-Cabrerizo JR, Montserrat-Gili JR, Massegur-Solench H, León-Vintró X, De Juan J, Fabra-Llopis JM. Management of sinonasal inverted papillomas and comparison of classification staging systems. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24(1):66–69. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2010.24.3421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YM, Kim HS, Park JY, Koo BS, Park YH, Rha KS. External vs endoscopic approach for inverted papilloma of the sino-nasal cavities: a retrospective study of 136 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:909–914. doi: 10.1080/00016480701774982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minovi A, Kollert M, Draf W, Bockmühl U. Inverted papilloma: feasibility of endonasal surgery and long-term results of 87 cases. Rhinology. 2006;44:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee TJ, Huang CC, Chen YW, Chang KP, Fu CH, Chang PH. Medially originated inverted papilloma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]