Abstract

Introduction

Various ossicular reconstruction materials and techniques have been described in literature using autologous ossicle, cortical bone, autologous cartilage, synthetic materials and implants like total/partial ossicular replacement prosthesis (TORP/PORP) etc., but it has always been a topic of controversy in terms of the efficacy, longevity and complications of the material or method used.

Material and Methods

This is a prospective, interventional, comparative, double-blind randomized control study which was done at a tertiary care center to compare outcomes of conventional and carved conchal cartilage (vertical strut) type III Tympanoplasty in terms of graft uptake and hearing gain. A total number of 52 cases were enrolled, randomized and allocated to 2 groups (26 each) i.e. group A (conventional type III) and group B (vertical strut technique).

Results

Graft uptake was seen in 25 (96.16%) patients in group B while it was observed in 23 (88.5%) cases in group A. Hearing gains were also better in group B.

Conclusion

This study suggests that Vertical Strut technique can be studied further as it gives better gains in Air Conduction threshold and A-B Gap along with graft uptake as it provides better middle ear space and ossicular / tympanic membrane interface resulting in better hearing.

Keywords: Ossiculoplasty, Tympanoplasty, Vertical strut, Vertical strut ossiculoplasty, Hearing gain

Introduction

Chronic otitis media (COM) is one of the most common and important middle ear disorders as it causes serious cost and resources implications for healthcare systems around the world particularly in developing countries. Surgical reconstruction of the tympanic membrane (TM) i.e. Tympanoplasty was pioneered by Wullstein and Zollner in 1952. Since then various types of graft materials have been applied for reconstruction of the tympanic membrane such as temporalis fascia, perichondrium, cartilage, fascia lata, vein and fat [1]. Tympanoplasty procedure followed a rapid evolutionary trend but various controversies over the procedure, techniques and graft materials also took place. To date, temporalis fascia is the most frequently employed material in tympanoplasty [2].

In certain circumstances such as retraction pockets, cholesteatoma, atelectasis, eustachian tube dysfunction, advanced middle ear pathology and large perforations; fascia grafts and conventional type III are found to succumb to infections and significant pressure gradient during the post-operative period leading to higher failure rates regardless of the surgical technique used. In such cases, a more rigid ossiculoplasty material such as cartilage is preferred because of its increased stability and resistance to middle ear pressure. The rigid nature of cartilage is thought to interfere with the sound transmission properties, even though it effectively prevents retraction and re-perforation [3]. Cartilage was first used in middle ear surgery for ossicular chain reconstruction in 1958 by Jansen. In 1963, Salen and Jansen first reported the use of cartilage composite grafts for tympanic membrane reconstruction [4–6]. Cartilage can be used either as a perichondrium/cartilage island flap, or palisade technique, or cartilage “shield” tympanoplasty, or inlay butterfly cartilage tympanoplasty. In type III cartilage tympanoplasty, cartilage is placed on the top of stapedial capitulum [7, 8].

Even after so many modifications in ossiculoplasty technique, the final results in hearing have been varied and compromising. Vertical strut technique was hypnotized to overcome the shortcomings of previous techniques. This study was aimed to compare outcomes of conventional and vertical strut type III tympanoplasty in terms of graft uptake and hearing gain.

Material and Methods

This is a prospective, interventional, comparative, double-blind randomized control study conducted in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology and head & neck surgery at a tertiary care hospital in India from June 2018 to November 2019 after approval from institutional ethics committee and research review board. Patients of COM with conductive hearing loss and necrosis of incus or incudo-stapedial joint with or without presence of cholesteatoma, granulations and polyp, who required either primary or revision surgery were included in the study after taking written and informed consent. Patients below 10 years and above 50yrs of age, patients with active discharging ear, intracranial complications, mixed or sensorineural hearing loss and those who were not willing to participate in the study were excluded. A total of 52 subjects were enrolled and randomized in two groups, group A and B with 26 cases in each by using computer generated random numbers obtained from www.random.org.

Surgical technique in group A: Type III Cartilage Tympanoplasty with Conventional technique (C.T.) i.e. keeping the graft over stapes head.

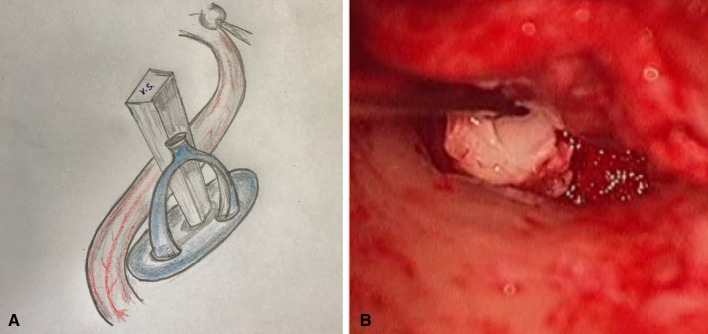

Surgical technique in group B: In vertical strut technique (VST), we make a triangular wedge of cartilage and keep it on the stapes foot plate (in presence or absence of stapes suprastructure) and chorda was preserved to hold it in place (Fig. 1). The Vertical strut (VS) maintains the Middle Ear Space, forms appropriate angulation/interface with tympanic membrane and provides better hearing.

Fig. 1.

Vertical strut Ossiculoplasty (Right ear) (a) Line diagram (b) Intraoperative picture

After obtaining detailed history, thorough general, otological examination and routine investigations for surgery were done. Baseline pure tone audiometry (PTA) was done to assess hearing status pre-operatively. Patients were than randomized and surgery was performed by an identified otolaryngologist who remained same throughout the study to minimize the inter-observer variation. A case number was attached with all patients after randomization. Neither investigator nor the patient knew about the technique which was used during surgery and data collection to apply double blinding. All patients were discharged on first post-operative day and suture removal was done after one week. Patients were then called at 1st month and 3rd month period for follow up or whenever needed. Clinical examination was done at all follow up period. Post-operative outcomes were measured in form of hearing gain and graft uptake. After 3 month of surgery, examination under microscope was done to check graft status and PTA was also done at the same time to observe post-operative hearing status.

At the end of study, data was compiled and analyzed statistically using SPSS 19.0 software and XL- Stat. Continuous data were summarized in form of mean and standard deviation. The difference in means of both groups was analyzed using student t` test. Count data summarized in form of proportions. The difference in proportions analyzed by chi square test / Fischer exact test. P value < 0.05 was taken as significant and > 0.05 as non-significant.

Results

After following strict guidelines of inclusion/exclusion criteria and removing defaulter or lost to follow up patients we included 52 cases in the study. Out of 52 cases, there were 28 male and 24 female patients i.e. male preponderance was noted here. In group A, 13 were males and 13 were females. In group B, there were 15 males and 11 females. Patients’ age ranged between 10–50 years with mean age of 26 years in Group A and 23.73 in Group B. There was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). Primary surgery was done in 25 cases (96.16%) and revision surgery was done in 1 case (3.84%) in group A. In Group B, primary surgery was done in 23 (88.5%) cases and in 3 cases (11.5%), revision surgery was done. Outcomes of both techniques were compared in terms of graft uptake and hearing gain. Graft uptake: Graft uptake was seen in 25 (96.16%) patients in group B who underwent cartilage tympanoplasty by vertical strut technique with residual perforation in 1 (3.84%) patient. In group A (C.T.), graft uptake was observed in 23 (88.5%) cases with residual perforation seen in 3 (11.5%) cases [Table 1].

Table 1.

Graft uptake rate of study groups

| Graft uptake | Surgery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Vertical Strut | Total | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| YES | 23 | 88.5 | 25 | 96.16 | 48 | 92.3 |

| NO | 3 | 11.5 | 1 | 3.84 | 4 | 7.7 |

| Total | 26 | 100.0 | 26 | 100.0 | 52 | 100.0 |

Chi-square = 0.271 with 1 degree of freedom; P = 0.603

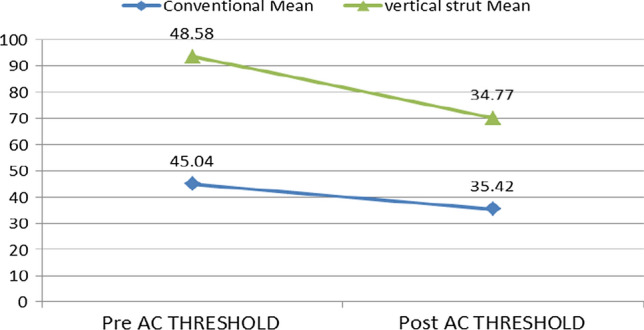

Hearing outcome: After comparing both groups, we observed that mean Air conduction (AC) threshold in Group A was 45.04 ± 10.26 dB preoperatively and post operatively after 3 months it was 35.42 ± 11.47 dB. Mean AC threshold in Group B was 48.58 ± 9.85 dB preoperatively and postoperatively after 3 months it was 34.77 ± 8.70 dB. Gain in mean AC threshold in Group A was 9.62 ± 13.51 dB while in Group B it was 13.81 ± 6.54 dB with P value of 0.161 which was statistically not significant (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of pre- and post-operative AC thresholds among study groups

| Conventional | Vertical strut | P value# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. deviation | Mean | Std. deviation | ||

| Pre-operative AC threshold (dB) | 45.04 | 10.26 | 48.58 | 9.85 | 0.210 |

| Post-operative AC threshold (dB) | 35.42 | 11.47 | 34.77 | 8.70 | 0.818 |

| Gain (dB) | 9.62 | 13.51 | 13.81 | 6.54 | 0.161 |

#Unpaired t test

Fig. 2.

Comparative values of mean AC threshold (in dB) of both study groups

Pre and post-operative (after 3 months) mean bone conduction (BC) threshold in group A was 13.89 ± 6.56 and 13.30 ± 8.41 dB respectively whereas in group B it was 15.58 ± 5.86 and 13.89 ± 5.68 dB respectively. Gain in Group A was 0.59 ± 10.90 dB and in Group B was 1.69 ± 5.24 dB with P value of 0.640 which was statistically not significant.

Mean A-B gap (ABG) in Group A was 31.15 ± 5.75 dB preoperatively and post operatively it was 22.12 ± 6.62 dB after 3 months. Mean A-B gap in Group B was 33.00 ± 8.39 dB and 20.88 ± 7.03 dB, pre and postoperatively. Closure in mean A-B gap in Group A was 9.03 ± 5.42 dB whereas in Group B it was 12.12 ± 7.24 dB with P value of 0.089 which was statistically not significant (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of pre- and post-operative A-B gap among study groups

| Conventional | Vertical strut | P value# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. deviation | Mean | Std. deviation | ||

| Pre-operative A–B gap (dB) | 31.15 | 5.75 | 33.00 | 8.39 | 0.359 |

| Post-operative A–B gap (dB) | 22.12 | 6.62 | 20.88 | 7.03 | 0.519 |

| Gain(dB) | 9.03 | 5.42 | 12.12 | 7.24 | 0.089 |

#Unpaired t test

Fig. 3.

Comparative values of mean air–bone gap (in dB) of both study groups

Discussion

The use of cartilage in tympanic membrane and ossicular repair dates back to 1960 when Utech first described the interposition of cartilage in ossiculoplasty [9]. Soon after that, Jansen and Salen also reported the use of auricular and nasal septal cartilage to reconstruct the ossicular chain in ears without a stapes suprastructure and for tympanic membrane perforations [4–6]. The one who popularized the use of cartilage in Tympanoplasty was Heermann. He claimed to have used the cartilage palisade technique for middle ear and mastoid cavity reconstruction since 1960, in over 13,000 cases [10, 11]. As cartilage is resistant to infection and has considerable stiffness, it is considered to be a more reliable and stable grafting material. On the contrary, temporalis fascia lacks stability and may shrink during healing [12–14]. In this study of Type III Cartilage Tympanoplasty with two different techniques, conchal cartilage was taken as a graft material for ossiculoplasty in place of tragal and other cartilages. The conchal cartilage lies within the operative field, it can be harvested easily and doesn’t give any residual functional defect at donor site. Although, obtaining the cartilage graft adds 5–10 min on an average to the procedure, its concave shape and its medial placement to the manubrium of the malleus results in a conical configuration of the reconstructed tympanic membrane. This more closely approximates the normal contour and shape of the tympanic membrane. Neither auricular hematomas nor perichondritis were encountered in the postoperative period. Cartilage is a reliable graft for tympanic membrane reconstruction as it is nourished by diffusion from the surface with the help of perichondrium and becomes well incorporated. The advantage of the cartilage over temporalis fascia cannot be overlooked as its toughness prevents the retraction of the neotympanic membrane because of its firm support. Some resistance to infection is also seen with cartilage during the healing period. Thus, the risk of recurrent perforation is reduced. In cases of severe Eustachian tube dysfunction, the cartilage maintains its integrity and resists resorption as well as retraction. Cartilage graft has been thought to have a very low metabolic rate, a factor helpful in maintaining intactness of the graft. Failure rate of cartilage graft was only 2.5% due to infection and inadequate postoperative antibiotic therapy in comparison to temporalis fascia group in which failure rate was 10% due to medialization of graft and infection in a study [15].

Desarda et al. conducted a study of 600 ear operations of various middle ear pathologies. The technical advantage of tragal cartilage and perichondrium graft in myringoplasty, ossiculoplasty and mastoid cavity obliteration were discussed and it was concluded that tragal perichondrium and cartilage is an ideal graft material for reconstructive tympanoplasty [16]. Khan et al. concluded that cartilage was a promising graft material to close tympanic membrane perforations. Better acoustic benefits may be obtained by thinning the cartilage. They described preparation of the graft by slicing it and presented 3 years’ experience of shield cartilage type tympanoplasty using sliced tragal cartilage perichondrium composite graft [17]. Mohamad et al. concluded that Tympanoplasty using cartilage with or without perichondrium has better morphological outcome than tympanoplasty using temporalis fascia. However, there was no statistically significant difference in hearing outcomes between the two grafts [18]. In a series of more than 300 patients, Bernal-Sprekelsen et al. used cartilage palisades in type 3 tympanoplasty with autologous incus, and inserted Ceravital and Ionos prostheses in both canal wall up and down situations. They observed a closure of the four-frequency pure tone average air–bone gap from 34.4 to 18.1 dB, with 62.1% of patients having an air–bone gap closure within 20 dB and 29.8% within 10 dB [19]. Ashish Vashishth et al. conducted a study to evaluate the functional and hearing outcomes using full thickness broad cartilage palisades for tympanic membrane reconstruction in type III tympanoplasty with titanium prostheses. They included 30 patients with tympanic membrane perforations or posterior mesotympanic retraction pockets undergoing type III ossicular reconstruction. The pre- and post-operative mean pure tone air-bone gaps were 32.4 ± 25 and 8.8 ± 15 dB, respectively [8]. Netra Aniruddha Pathak and Vidya Vasant Rokade conducted a study to assess the hearing results in patients undergoing canal wall down mastoidectomy with cartilage augmented type III tympanoplasty. Patients of 6–50 years of age with the diagnosis of Chronic Otitis Media (Squamous) with conductive or mixed hearing loss, underwent cartilage augmentation were included in the study. The results concluded that mean of pre- and post-operative air bone gap were 37.5db and 29.7db respectively with net gain of 7.8 db [20]. Efthymios Kyrodimos et al. reported the hearing results of 52 patients following type III cartilage “shield” tympanoplasty. The mean age was 32.4 years (range, 7 to 72 years). With the mean follow-up 24 months (range—12 to 36 months), the graft uptake was successful in all patients. The average hearing improvement was 11.22 dB (P = 0.0001). An air–bone gap of 25 dB or less was achieved in 41 (78.8%) patients [7].

In the present study, Closure in mean A-B gap was better in Group B (12.12 ± 7.24 dB) than Group A (9.03 ± 5.42 dB) although it was statistically not significant (Table 3, Fig. 3). Better results were seen in air conduction thresholds and A–B gap in Group B (V.S.T.), although it also seems statistically insignificant due to small sample size, making it a limiting factor in the study.

Conclusion

Present study of Type III cartilage Tympanoplasty concluded that Vertical Strut technique is a novel technique which might give better hearing along with better graft uptake as compare to Conventional technique as it provides better middle ear space, better ossicular/tympanic membrane interface resulting in better hearing; but further consolidated studies are required with large sample size and long duration to validate these results and to make a consolidated statement with statistical significance.

Author Contribution

New author added is Dr Shivam Sharma who has helped in revision of this manuscript in difficult COVID conditions.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arora N, Passey JC, Agarwal AK, Bansal R. Type 1 tympanoplasty by cartilage palisade and temporalis fascia technique: a comparison. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;69(3):380–384. doi: 10.1007/s12070-017-1137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasscock ME, House WF. Homograft reconstruction of the middle ear. Laryngoscope. 1968;78:1219–1225. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onal K, Arslanoglu S, Songu M, Demiray U, Demirpehlivan IA. Functional results of temporalis fascia versus cartilage tympanoplasty in patients with bilateral chronic otitis media. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(1):22–25. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111002817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansen C (1961) The use of cartilage in hearing restorative operations [in German]. In: 7th international congress of otology, rhinology and laryngology 1961. Paris

- 5.Salen B. Myringoplasty using septum cartilage. Acta Otolaryngol. 1964;188(suppl 188):82–91. doi: 10.3109/00016486409134544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansen C. Cartilage tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1963;13:1288–1302. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyrodimos E, Sismanis A, Santos D (2007) Type III cartilage “shield” tympanoplasty: an effective procedure for hearing improvement. Otolaryngol—Head Neck Surg 136(6):982–5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Vashishth A, Mathur NN, Verma D. Cartilage palisades in type 3 tympanoplasty: functional and hearing results. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66(3):309–313. doi: 10.1007/s12070-014-0717-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utech H. Improved final hearing results in tympanoplasty by changes in the operation technic [in German] Z Laryngol Rhinol Otol. 1960;39:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heermann J. The author’s experience of using free temporalis fascia and the cartilage bridge from stapes to tympanic membrane for tympanoplasty and the reduction of radical mastoid cavity [in German] Zeitschrift fur Laryngologie, Rhinologieund Otologie. 1962;41:141–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heermann J. Autogaft tragal and conchal palisade cartilage and perichondrium in tympanomastoid reconstruction. Ear Nose Throat J. 1992;71:344. doi: 10.1177/014556139207100803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aidonis I, Robertson TC, Sismanis A. Cartilage shield tympanoplasty: a reliable technique. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26(5):838–841. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000185046.38900.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumann A, Kevenhoerster K, Gostian AO. Long-term results of palisade cartilage tympanoplasty. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31(6):936–939. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e71479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Indorewala S. Dimensional stability of the free fascia grafts: an animal experiment. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(4):727–730. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200204000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma N, Sharma P, Sharma P, Gourav K, Goyal VP. Comparison of otological and audiological outcome of type-I tympanoplasty using composite tragal perichondrium and temporalis fascia as graft. Int J Otorhinol Head Neck Surg. 2018;4(5):1182. doi: 10.18203/issn.2454-5929.ijohns20183455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desarda KK, Bhisegaonkar DA, Gill S. Tragal perichondrium and cartilage in reconstructive tympanoplasty. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57(1):9–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02907617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan MM, Parab SR. Primary cartilage tympanoplasty: our technique and results. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32(5):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohamad SH, Khan I, Hussain SM. Is cartilage tympanoplasty more effective than fascia tympanoplasty? A Syst Rev Otol Neurotol. 2012;33(5):699–705. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318254fbc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Lliso MD, Gonzalo JJ. Cartilage palisades in type III tympanoplasty: anatomic and functional long-term results. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(1):38–42. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pathak NA, Rokade VV. Evaluation of results of cartilage augmentation in Type III tympanoplasty. Bengal J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25(3):119–123. doi: 10.47210/bjohns.2017.v25i3.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]