Abstract

This research aimed to detect Escherichia coli O157:H7 in milk based on immunomagnetic probe separation technology and quenching effect of gold nanoparticles to Rhodamine B. Streptavidin-modified magnetic beads (MBs) were combined with biotin-modified antibodies to capture E. coli O157:H7 specifically. Gold nanoparticle (AuNPs) was incubated with sulfhydryl-modified aptamers (SH-Aptamers) to obtain the Aptamers-AuNPs probe. After magnetic beads captured target bacteria and formed a sandwich structure with the gold nanoprobe, Rhodamine B was added into complex to obtain fluorescent signal changes. Our results demonstrated that the established method could detect E. coli O157:H7 in the range of 101–107 CFU/mL, and the limit of detection (LOD) was 0.35 CFU/mL in TBST buffer (pH = 7.4). In milk simulation samples, the LOD of this method was 1.03 CFU/mL. Our research provides a promising approach on the detection of E. coli O157:H7.

Keywords: Immunomagnetic, Gold nanoparticle, Aptamer, Rhodamine B, Foodborne pathogen

Introduction

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is one of the common foodborne pathogens (Croxen et al., 2013). Classic pathological types of E. coli include enterinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (Braz et al., 2020). E. coli O157:H7 is also called enterhaemorrhagic E. coli, which is a special serotype of EHEC. It can spread through food and drinking water, posing a serious threat to human health and cause a severe economic burden (Bai et al., 2020). It can also cause diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic (Su and Brandt, 1995; Zhu et al., 2011). In addition, E. coli O157:H7 has strong adaptability to temperature, pH and drying environment, which makes it easily to contaminate many kinds of food, such as beef, milk (Keba et al., 2020) and pasta (Gieraltowki et al., 2017). Therefore, it is important to establish a rapid and effective method for the detection of foodborne pathogens.

There are several traditional methods for the detection of foodborne pathogens. The standard detection method, pathogen culture and colony counting, usually requires several days to identify the target pathogens (Liu et al., 2018). Nucleic acid amplification (e.g., PCR (Xu et al., 2018)), protein identification (e.g., mass spectrometry and chromatography (Chui et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2019)) and immunological reactions (e.g., ELISA (Mirhosseini et al., 2017) are also the commonly used methods. Although PCR can provide sensitive and specific detection, it easily gets false positive results because of the contamination of nucleic acid. The limit of detection (LOD) of combination of mass spectrometry and chromatography is generally around 103 CFU/mL (Chen et al., 2019).However, maintenance cost of mass spectrometry and chromatograph is relatively high and the equipment is expensive, so it is difficult to be used in rapid detection. Although the detection time of ELISA usually required for several minutes to several hours, the LOD of bacteria is only about 104 CFU/mL (Parma et al., 2012). Additionally, ELISA detection kit is expensive, which makes it cannot be used widely in routine test either.

Recently, biosensors have attracted much attention. They were proposed as the promising methods to replace the traditional diagnostic methods of pathogenic bacteria detection and quantification (Wu et al., 2019). Immunomagnetic separation (IMS) technology is a separation and identification technology based on the specific reaction of antigen and antibody. It is very suitable for food pretreatment due to its dual properties of bacteria’s concentration and separation; therefore, it shows high sensitivity for pathogen detection in complex food samples (Kim et al., 2018).

Nanotechnology is the combination of science, engineering and technology. It has been applied in many fields such as chemistry (Zhang et al., 2021), biology (Yilmaz et al., 2021), physics (Nancy et al., 2021), and medicine (Sun et al., 2021). The gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) have been increasingly applied in the field of analysis which based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Because of its unique optical characteristics, inertness and stability in biological fluids, AuNPs have been widely used in the microbial analysis, detection and identification. Its advantages include simple synthesis, good biocompatibility, and quenching effect on the fluorescence of Rhodamine B (Zhang et al., 2013).

Aptamer is a type of functional nucleic acids selected in vitro through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Ex-ponential enrichment (SELEX) (Ni et al., 2017). It has many advantages: high affinity and specificity, embracing production automation, good stability, desirable biocompatibility and flexible chemical-modification (Srinivasan et al., 2018). This study has established a method that can quickly detect E. coli O157: H7 based on the above advantages of these biosensors. IMS was used to separate and concentrate target bacteria. Both AuNPs and aptamers were used to form a probe (AuNPs-aptamer probe) that can specifically recognize the target bacteria. When Rhodamine B was added, the IMBs-Bacteria-AuNPs can quenched the fluorescence of Rhodamine B via FRET significantly.

This method not only can be operated quickly and simply, but has a wide detection range, a low LOD and a good specificity, which can be applied to the detection of daily substances.

Materials and methods

Materials

Streptavidin-modified magnetic beads were provided by Shanghai Shenggong Biological Technology Co., Ltd. Tween 20 was supplied by Yu bo Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Skimmed milk powder was bought from local supermarket (Yili Industrial Group (Inner Mongolia) Co., Ltd.). E. coli O157:H7 antibody, HAuCl4·3H2O was from Alfa Aesar (China) Chemical Co., Ltd., and was dissolved to 1% (w/v). Trisodium citrate, Sodium chloride (NaCl), Glacial acetic acid, concentrated hydrochloric acid and concentrated nitric acid were came from Beijing Chemical Plant. E. coli O157: H7 aptamer sequence is: 5'-SH-tgagcccaagccctggtatgcggataacgaggtattcacgactggtcgtcaggtatggttggcaggtctactttgggatc was synthesized by Biotech Bioengineering (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Rhodamine B was bought from Beijing Solarbao Technology Co., Ltd. Distilled water was made by Lab of Jilin University School of Public Health. Inactivated E. coli O157: H7, B. melitensis 16 M, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium, Shigella flexneri and Vibrio parahaemolyticus were provided by Jilin Province Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau.

Preparation of immunomagnetic beads (IMBs)

In order to redisperse the magnetic beads (MBs) and increase the surface area of reaction, the MBs were sonicated before use. 100 µL magnetic nanoparticles (50 mg/mL) were washed by 1 mL TBST (Tris buffered saline with Tween 20) for 3 times. Then 5 µL of E. coli O157: H7 antibody (10 mg/mL) were added into MBs and incubated on vertical suspension at 25 °C for 60 min. The supernatant was discarded and washed with 1 mL TBST to remove the unbound antibodies. Then 1 mL 3% (w/v) skim milk powder were added and incubated at 25 °C for 60 min to block the sites on the magnetic beads which didn’t bound to antibodies (Li et al., 2019).

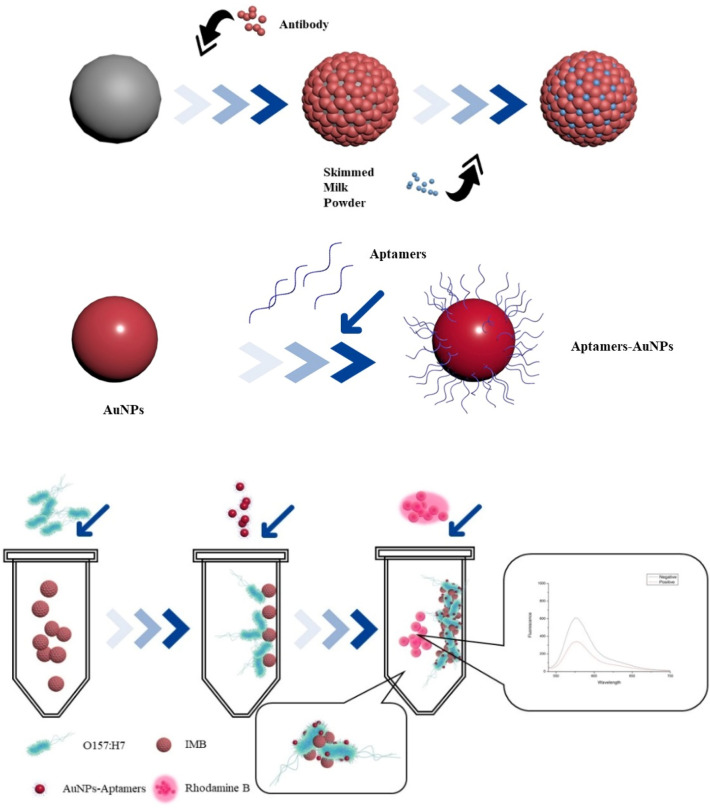

Then the conjugate was separated magnetically, washed by TBST and resuspended in 1 mL TBST buffer. IMBs were stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for later use (Fig. 1). The final concentration of IMBs was 5 mg/mL.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of immunomagnetic probe (IMBs), Aptamers-AuNPs probe and experimental principle

MBs and IMBs were characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM) (200 kV). Fourier infrared transform spectrometer (FT-IR) was set KBr as the scanning background. Wavenumber was set to 4000–400/cm, scanned the samples at a speed of 2/cm.

Preparation of gold nanoprobe

Trisodium citrate reduction method was used for the synthesis of AuNPs (Srinivasan et al., 2018). In short, 500 µL of 1% (w/v) chloroauric acid was added into 50 mL distilled water, and heated to boil. Then 3 mL of 1% (w/v) trisodium citrate were added immediately, and the solution would change from blue-gray to wine-red gradually (Zhang et al., 2016). This process took about 5 min. After cooling, UV absorption of AuNPs was measured.

1 mL AuNPs were incubated with 2 µL of aptamer (10 µM) that specifically recognized E. coli O157: H7 for 60 min, then centrifuged (13,201 × g, 10 min) and stored in refrigerator at 4 °C for later use (Fig. 1).

AuNPs and Aptamers (Apts)-AuNPs was characterized using TEM (200 kV). The UV absorption spectra were scanned between 600 and 450 nm.

Establishment of a rapid detection method of O157: H7

When the target bacteria exist, IMBs capture the bacteria and form an IMBs-bacteria complex. After adding the assembled Apts-AuNPs probe, IMBs, bacteria and Apts-AuNPs can form an IMBs-bacteria-AuNPs sandwich structure. The fluorescence of Rhodamine B was quenched by the AuNPs (Fig. 1).

Experiment result can be evaluated through the difference of fluorescence intensity of negative samples (F0) and positive samples (F).

Results and discussion

Characterization of nanoprobes

TEM (Transmission Electron Microscope) characterization of MBs and IMBs

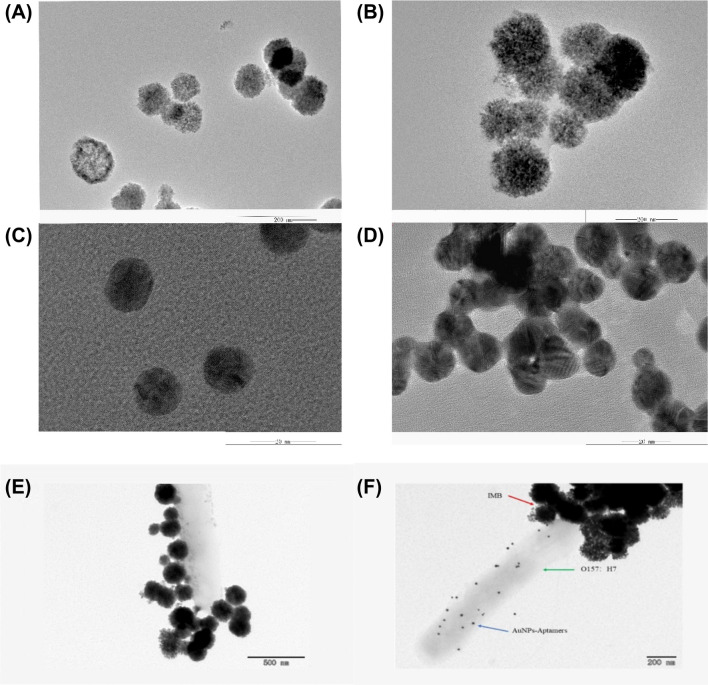

The average particle size of the streptavidin-modified magnetic beads was about 73 ± 6 nm. After coupling with the antibody, the particles size was increased to about 128 ± 7 nm. The cloud-like film confirmed that surface of magnetic beads has been coated by antibodies (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

TEM characterization of (A) (MBs)magnetic nanoparticles (B) (IMBs)immunomagnetic nanoprobe (C) AuNPs (D) AuNPs-Aptamers (E) IMBs + Bacteria (F):IMBs-Bacteria-AuNPs Sandwich Structure

TEM characterization of AuNPs and AuNPs-aptamers

Afterwards, TEM characterization of AuNPs and AuNPs-Apts were performed to check the formation state of AuNPs-Apts probes.

The particle size of single AuNPs was about 30 ± 7 nm, while after coupling with the aptamer, the particle size of Apts-AuNPs was increased to 44 ± 4 nm, which shows slightly larger than AuNPs. It can be seen in the TEM that there is a bright white area around the gold particles. The aggregation state has changed slightly too. This proved that the aptamer was successfully coupled with the AuNPs (Fig. 2c, d).

TEM characterization of IMBs-Bacteria-AuNPs sandwich structure

It can be seen in Fig. 2e that target bacteria was successfully captured by the IMBs. It can be seen from Fig. 2f that the expected sandwich structure (IMBs-Bacteria-AuNPs) has been formed.

FT-IR characterization of IMBs

It can be seen from Fig. 3a that after the magnetic beads and the antibody was combined, the amide bond (CO–NH) peak (1618.65) had a stretching change. Therefore, we can confirm that MBs were modified by the antibody successfully.

Fig. 3.

FT-IR characterization of IMBs and UV absorption spectrum of Aptamers-AuNPs probe

UV–vis-spectrum of golden nanoprobe (AuNPs-Aptamers)

The AuNPs was coupled with the SH-Aptamers by Au–S bonds, which caused the size of the AuNPs increase and the shape change slightly. It can be seen from Fig. 3b that after coupling SH-aptamers, UV absorption peak of AuNPs was shifted from 520 to 522 nm.

Optimization of experimental conditions

Optimization of IMBs probes

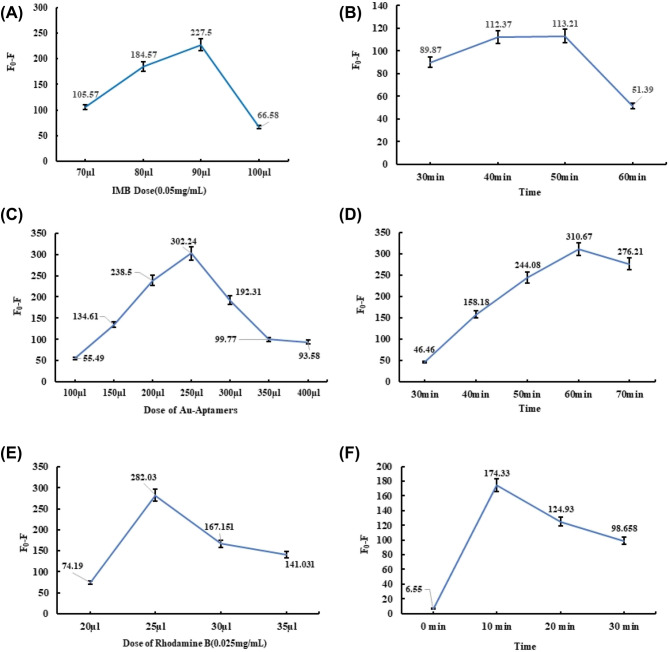

In order to obtain best detection signals, the experimental conditions are optimized as follows. We used the dose of IMBs at 70 μL (0.35 mg/mL), 80 μL (0.40 mg/mL), 90 μL (0.45 mg/mL) and 100 μL (0.50 mg/mL) respectively, and the incubation time of IMBs-Bacteria complex at 30 min, 40 min, 50 min, and 60 min respectively. excitation wavelength (EX) was set to 530 nm and the emission wavelength (EM) was 576 nm. The fluorescence was measured three times and took the average. Fluorescence difference (F0-F) was used to evaluate results of experiment.

With the increase of IMBs amount, the difference of fluorescence signal (F0-F) was also increased, but when the amount of IMBs was exceeded 90 μL, the fluorescence difference (F0-F) was reduced (Fig. 4a). It is considered that high concentrations of IMBs lead to its aggregation, reduce the specifically bind sites (Li et al., 2019). When the incubation time was less than 50 min, the fluorescence difference (F0-F) was increased. However, when the incubation time exceeded 50 min, the fluorescence difference (F0-F) was decreased. According to the optimized results of the experiment, 90 μL of IMBs, and 50 min of incubation were chosen as the best experimental condition of IMBs probes (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Difference of negative fluorescence to positive fluorescence (A) Optimization of the amount of IMBs; (B) Optimization of the reaction time of the complex of IMBs-Bacteria (C) Optimization of the amount of Aptamers-AuNPs probe; (D) Optimization of the reaction time of the complex of IMBs-Bacteria-Aptamers-AuNPs (E) Optimization of the amount of Rho B. (F) Optimization of the reaction time between the IMBs-Bacteria-Aptamers-AuNPs and Rho B

Optimization of gold nanoprobe

Similarly, the dose and incubation time of Apts-AuNPs probe were optimized. We set Apts-AuNPs probe to 100 µL (0.01 mg/mL), 150 µL (0.015 mg/mL), 200 µL (0.02 mg/mL), 250 µL (0.025 mg/mL), 300 µL (0.03 mg/mL) and 350 µL (0.035 mg/mL) respectively, and measured the difference of fluorescence signal (F0-F) of the complex. When Apts-AuNPs probe was less than 250 μL, the fluorescence difference between the negative and positive was increase. When the Apts-AuNPs probe’s amount exceeded 250 μL, the fluorescence difference was decrease with probe amount increases. According to the optimized results of the experiment, we chose 250 μL of the Apts-AuNPs probe as the best dosage (Fig. 4c).

The incubation time of the Apts-AuNPs probe was set to 30 min, 40 min, 50 min, 60 min and 70 min respectively. When the incubation time of Apts-AuNPs probe was less than 60 min, the fluorescence difference between the negative and positive samples (F0-F) increased gradually. When the Apts-AuNPs probe incubation time was more than 60 min, the fluorescence difference decreased instead. It is considered to be caused by the competition of Apts-AuNPs probe to target bacteria (Wang et al., 2020). According to the fluorescence difference, the incubation time of the gold nanoprobe was set as 60 min (Fig. 4d).

Optimization of rhodamine B

The same method was used to find the best dose and incubation time of Rhodamine B. Rhodamine B was set to (0.025 mg/mL) to 20 μL, 25 μL, 30 μL, and 35 μL respectively. When Rhodamine B was less than 25 μL, the fluorescence difference (F0-F) was increased with Rhodamine B increases. When Rhodamine B exceeded 25 μL, F0-F was decreased with the Rhodamine B amount increase. The best amount of Rhodamine B was 25 μL (Fig. 4e).

The incubation time of Rhodamine B was set to 0 min, 10 min, 20 min, and 30 min respectively, then compared the fluorescence intensity of the complex through F0-F. As shown in Fig. 4f, when the incubation time of Rhodamine B was less than 10 min, the fluorescence difference between the negative and positive samples was increased gradually. On the contrary, when the incubation time of the Rhodamine B was higher than 10 min, the difference was decreased instead. Therefore, we took 10 min as the best incubation time of Rhodamine B.

Sensitivity

Specificity and sensitivity of this detection method were evaluated under the best experimental conditions. The target bacterial suspension concentration was 101–107 CFU/ mL, and as the target bacterial suspension concentration increased, the fluorescence signal of the complex gradually decreased (Fig. 5a). As shown in Fig. 5b, the target bacterial suspension concentration showed a good linear correlation with the fluorescence difference (F0-F). The regression equation was Y = 36.956X-4.9429 (R2 = 0.9918). And LOD was 0.35 CFU/ mL.

Fig. 5.

Fluorescence intensity difference of different concentrations of bacterial liquid (101–107 CFU/mL) a Fluorescence spectra; b Standard curve of the fluorescence intensity (F0-F) c Comparison of fluorescence difference between target bacteria and non-target bacteria Fluorescence intensity difference of different concentrations of bacterial liquid (101–107 CFU/mL) in simulated sample d Fluorescence intensity; e Standard curve of the fluorescence intensity (F0-F)

Specificity

Six kinds of non-target foodborne pathogens including B. melitensis 16 M, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium, Shigella flexneri and Vibrio parahaemolyticus were used to evaluate the specificity of this detection method. These six interfering bacteria were used as negative groups, and the TBST buffer was used as a blank control group.

There was no significant difference in the fluorescence signal between the blank control group (TBST) and the six interference bacteria groups (Fig. 5c). Compared with the negative group, the fluorescence difference of control group and the positive group changed significantly, which was higher than that of the blank and negative control groups obviously. The F0-F values of the positive and negative group were significantly different. These results clearly showed that this method can identify target bacteria with high specificity and sensitivity.

Simulated sample

Milk was used as a simulation sample in this experiment. When the target bacteria suspension concentration was at the range of 101–107 CFU/mL, as the target bacterial suspension concentration increased, the fluorescence intensity of the complex gradually decreased (Fig. 5d). F0-F and E. coli O157:H7 concentration showed a good linear correlation (Fig. 5e). The regression equation was Y = 12.697X–5.9771 (R2 = 0.9423). The LOD was calculated using the ratio of three times the standard deviation of the fluorescent signal of the negative sample to the slope of the standard curve, and the LOD in milk sample was 1.03 CFU/mL. In this study, two nanoprobes, which can recognize E. coli O157:H7 specifically was synthesized. An experimental method that can detect E. coli O157: H7 quickly and sensitively was established. This method does not require pre-enrichment, and the whole experiment only needed about two hours. It is much simple and faster than other traditional detection methods (Arthur et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2014), and shows superior specificity and sensitivity (Xu et al., 2018; Priyanka et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2020). The LOD of the simulated sample was 1.03 CFU/mL. In addition, the experimental protocol also can be used to detect other foodborne pathogens even other harmful chemicals.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission (the Grant Number: 2020C038-7), the Development of Science and Technology, Jilin Province, China (Grant Number: 2018010195JC), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 81401721), the Education Department of Jilin Province, China (Grant Number: JJKH20180239KJ) and the Health and Family Planning Commission of Jilin Province (Grant Number: 2017J074)

Author contributions

FL, KX, CZ conceived and designed the study. FL, DW, SY, lirui Ge performed the assay of experimental detection. JZ, YZ and YW analyzed the data. FL drafted the manuscript. CZ and XS provided constructive opinions and suggestions. KX, CZ, XS, YL, JL and MJ reviewed and made improvements in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Fengnan Lian, Email: 1290497932@qq.com.

Dan Wang, Email: 1610041471@qq.com.

Shuo Yao, Email: yaoshuo20@mails.jlu.edu.cn.

Lirui Ge, Email: gelr19@mails.jlu.edu.cn.

Yue Wang, Email: wangyue19@mails.jlu.edu.cn.

Yuyi Zhao, Email: yyzhao19@mails.jlu.edu.cn.

Jinbin Zhao, Email: jinbinzhao125@163.com.

Xiuling Song, Email: songxiuling@jlu.edu.cn.

Chao Zhao, Email: czhao0529@jlu.edu.cn.

Jinhua Li, Email: jinhua1@jlu.edu.cn.

Yajuan Liu, Email: yjliu@jlu.edu.cn.

Minghua Jin, Email: jinmh@jlu.edu.cn.

Kun Xu, Email: xukun@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- Arthur TM, Bosilevac JM, Nou X, Koohmaraie M. Evaluation of culture-and PCR-based detection methods for Escherichia coli O157:H7 in inoculated ground beeft. Journal of Food Protection. 68: 1566-1574 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bai H , Bu S , Liu W , Wang C , Li Z , Hao Z , Wan J , Han Y . An electrochemical aptasensor based on cocoon-like DNA nanostructure signal amplification for the detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Analyst. 145: 7340-7348 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Braz VS, Melchior K, Moreira CG. Escherichia coli as a multifaceted pathogenic and versatile bacterium. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10: 548492 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen CT, Yu JW, Ho YP. Identification of bacteria in juice/lettuce using magnetic nanoparticles and selected reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 27: 575-584 (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chui H, Chan M, Hernandez D, Chong P, McCorrister S, Robinson A, Walker M, Peterson LA, Ratnam S, Haldane DJ, Bekal S, Wylie J, Chui L, Westmacott G, Xu B, Drebot M, Nadon C, Knox JD, Wang G, Cheng K. Rapid, sensitive, and specific Escherichia coli H antigen typing by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight-based peptide mass fingerprinting. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 53: 2480-5 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB. Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26: 822-880 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gieraltowski L, Schwensohn C, Meyer S, Eikmeier D, Medus C, Sorenson A, Forstner M, Madad A, Blankenship J, Feng P, Williams I. Notes from the field: Multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections linked to dough mix-United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66: 88-89 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Keba A, Rolon ML, Tamene A, Dessie K, Vipham J, Kovac J, Zewdu A. Review of the prevalence of foodborne pathogens in milk and dairy products in Ethiopia. International Dairy Journal. 109: 104762 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim JH, Yoo JG, Ham JS, Oh MH. Direct Detection of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella spp. in animal-derived foods using a magnetic bead-based immunoassay. Korean Journal Food Science Animal Resource. 38: 727-736 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li X , Zhao C , Liu Y , Li Y , Lian F , Wang D , Zhang Y , Wang J , Song X , Li J , Yang Y , Xu K. Fluorescence signal amplification assay for the detection of B. melitensis 16M, based on peptide-mediated magnetic separation technology and a AuNP-mediated bio-barcode assembled by quantum dot technology. Analyst. 144: 2704-2715 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Wei Y, Cao Y, Zhu D, Ma W, Yu Y, Guo M. Ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence detection of Staphylococcus aureus via enzyme-free branched DNA signal amplification probe. Biosens & Bioelectron. 117: 830-837 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Luo K, Ryu J, Seol IH, Jeong KB, You SM, Kim YR. Paper-based radial chromatographic immunoassay for the detection of pathogenic bacteria in milk. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 11: 46472-46478 (2019) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mirhosseini SA, Fooladi AAI, Amani J, Sedighian H. Production of recombinant flagellin to develop ELISA-based detection of Salmonella Enteritidis. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 48: 774-781 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nancy P, Jose J, Joy N, Valluvadasan S, Philip R, Antoine R, Thomas S, Kalarikkal N. Fabrication of silver-decorated graphene oxide nanohybrids via pulsed laser ablation with excellent antimicrobial and optical limiting performance. Nanomaterials (Basel). 11: 880 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ni X, Xia B, Wang L, Ye J, Du G, Feng H, Zhou X, Zhang T, Wang W. Fluorescent aptasensor for 17β-estradiol determination based on gold nanoparticles quenching the fluorescence of Rhodamine B. Analytical Biochemistry. 523: 17-23 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parma YR, Chacana PA, Lucchesi PM, Rogé A, Granobles Velandia CV, Krüger A, Parma AE, Fernández-Miyakawa ME. Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using chicken egg yolk IgY antibodies. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 84 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Priyanka B, Patil RK, Dwarakanath S. A review on detection methods used for foodborne pathogens. The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 144: 327-338 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan S, Ranganathan V, DeRosa MC, Murari BM. Label-free aptasensors based on fluorescent screening assays for the detection of Salmonella Typhimurium. Analytical Biochemistry. 559: 17-23 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Su C, Brandt LJ. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in humans. Annals of Internal Medicine. 123: 698-714 (1995) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sun S, Ding Z, Yang X, Zhao X, Zhao M, Gao L, Chen Q, Xie S, Liu A, Yin S, Xu Z, Lu X. Nanobody: A small antibody with big implications for tumor therapeutic strategy. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 16: 2337-2356 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Lian F, Yao S, Liu Y, Wang J, Song X, Ge L, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Zhao C, Xu K. Simultaneous detection of three foodborne pathogens based on immunomagnetic nanoparticles and fluorescent quantum dots. ACS Omega. 5: 23070-23080 (2020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wu Q, Zhang Y, Yang Q, Yuan N, Zhang W. Review of electrochemical DNA biosensors for detecting food borne pathogens. Sensors. 19: 4916- (2019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu D, Ji L, Wu X, Yan W, Chen L. Detection and differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by multiplexed real-time PCR. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 64: 809-815 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz E, Sarp G, Uzcan F, Ozalp O, Soylak M. Application of magnetic nanomaterials in bioanalysis. Talanta. 229: 122285 (2021) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang J, Liu B, Liu H, Zhang X, Tan W. Aptamer-conjugated gold nanoparticles for bioanalysis. Nanomedicine (Lond). 8: 983-93 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang D, Yang J, Ye J, Xu L, Xu H, Zhan S, Xia B, Wang L. Colorimetric detection of bisphenol A based on unmodified aptamer and cationic polymer aggregated gold nanoparticles. Analytical Biochemistry. 499: 51-56 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang M, Xu X, Gu Y, Cheng X, Hu J, Xiong K, Jiang Y, Fan T, Xu JM. Zhang, M., Xu, X., Gu, Y., Cheng, X., Hu, J., Xiong, K., Jiang, Y., Fan, T., & Xu, J. Porous and nanowire-structured NiO/AgNWs composite electrodes for significantly-enhanced supercapacitive and electrochromic performances. Nanotechnology. 32: (2021) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Lin CW, Wang J, Oh DH. Advances in rapid detection methods for foodborne pathogens. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24: 297-312 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao Y, Zeng D, Yan C, Chen W, Ren J, Jiang Y, Jiang L, Xue F, Ji D, Tang F, Zhou M, Dai J. Rapid and accurate detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in beef using microfluidic wax-printed paper-based ELISA. Analyst. 145: 3106-3115 (2020) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhu P, Shelton DR, Li S, Adams DL, Karns JS, Amstutz P, Tang CM. Detection of E. coli O157:H7 by immunomagnetic separation coupled with fluorescence immunoassay. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 30: 337-341 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed]