Abstract

Cribriform plate is the commonest site of Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, its fragility and juxtaposition of arachnoid’s investment to the bone, where the olfactory nerve pierces the skull, is a vulnerable site for CSF leak. Endoscopic transnasal approach has been the main stay for CSF leak repair over the past 2 decades. The technique and surgical steps of Endoscopic Surgical Repair of Cribriform CSF Leak using Free Septal Mucosal Graft without Postoperative Nasal packs are presented. Transnasal endoscopic CSF leak repair under General anesthesia with free mucosal graft, the critical steps include visualize the site of leak, lateralisation of middle turbinate, defect site cauterised with bipolar cautery. Free mucosal from contralateral side of the septum was placed as overlay technique. Graft stabilised with surgicel after ensuring adequate contact between the graft and the defect site. If the defect site is large then fat harvested from thigh is used as bath plug the defect, then free mucosal graft is kept supported by surgicel. Finally the middle turbinate was medialized and sutured with 3 0′ Vicryl with nasal septum to support the graft and also to stabilize the middle turbinate as a quilting stich. No fibrin glue was used in our case series. No nasal packing was done. Patients discharged on 2nd or 3rd postoperative day. This technique provides consistent good results reduced operating time of 40 min, no post-operative morbidity, early mobilisation, with 100% success rate and with added advantage of no nasal packing, patient can easily breathing through the nose postoperatively & no recurrence on long follow up.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12070-020-02107-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid, CSF, Rhinorrhoea, Spontaneous, Cribriform, CSF leak, Cerebrospinal fluid fistula, Free mucosal graft, No postoperative nasal packing

Introduction

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea is leakage of cerebrospinal fluid from the nose due to communication with subarachnoid space with disruption of dura along with bony defect [1]. Aetiology of CSF cribriform rhinorrhoea is classified as traumatic (60%) and spontaneous (40%) [2]. Traumatic include accidental and iatrogenic while nontraumatic (spontaneous) includes idiopathic, benign intracranial hypertension (BIH), vit. D deficiency, skullbase defects etc. Minimally invasive endoscopic approach has become the standard treatment for CSF rhinorrhoea, with more than 90% success rate, with lower rate of morbidity and mortality as compared to the traditional intracranial techniques [3, 4].

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the patients who presented to our Center with CSF rhinorrhoea. Patients with unilateral spontaneous and traumatic cribriform CSF leaks were included in our retrospective study, while those with spontaneous leak from other site and patients who lost postoperative follow up were excluded from the study. 18 patients were included in the study. Several parameters were evaluated including; age, sex, site of the CSF leak and follow up. The most common presenting complaint was continuous unilateral watery nasal discharge; other possible symptoms include headache, meningitis, hyposmia, meningism. The diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhoea was based on clinical history. The presence and site of CSF leak was confirmed by CT cisternogram scan (intrathecal contrast study) coronal cuts (0.75 or 1 mm) of the paranasal sinuses. All patients underwent Transnasal endoscopic CSF leak repair with free mucosal graft.

Operative Procedure

Anaesthesia This procedure is done under general anaesthesia.

Positioning Patient is positioned in a supine posture with reverse trendelenburg position, head end is elevated to 30°, to decrease venous return. Endoscope- ‘0’ degree 4 mm rigid endoscope is used, along with a high definition camera.

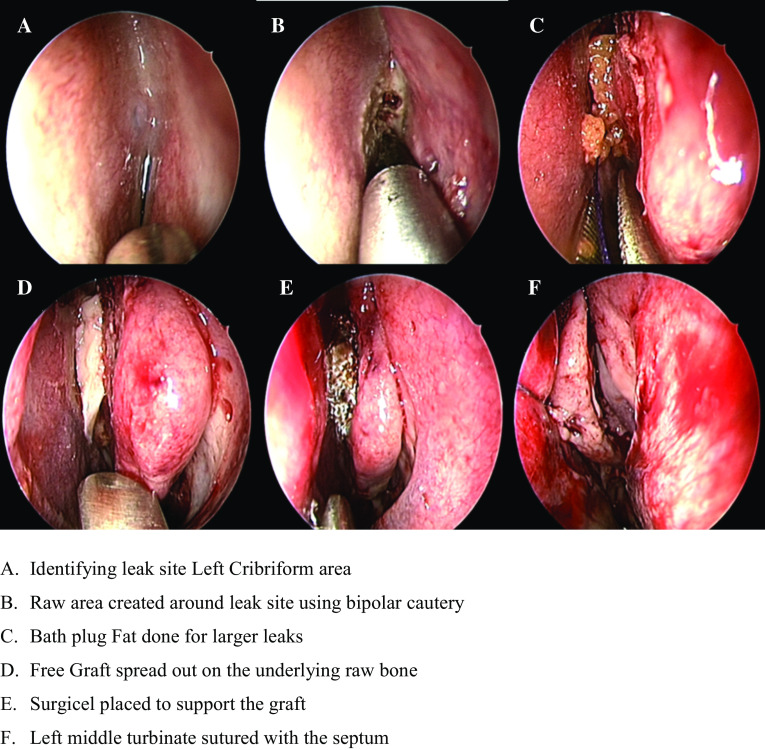

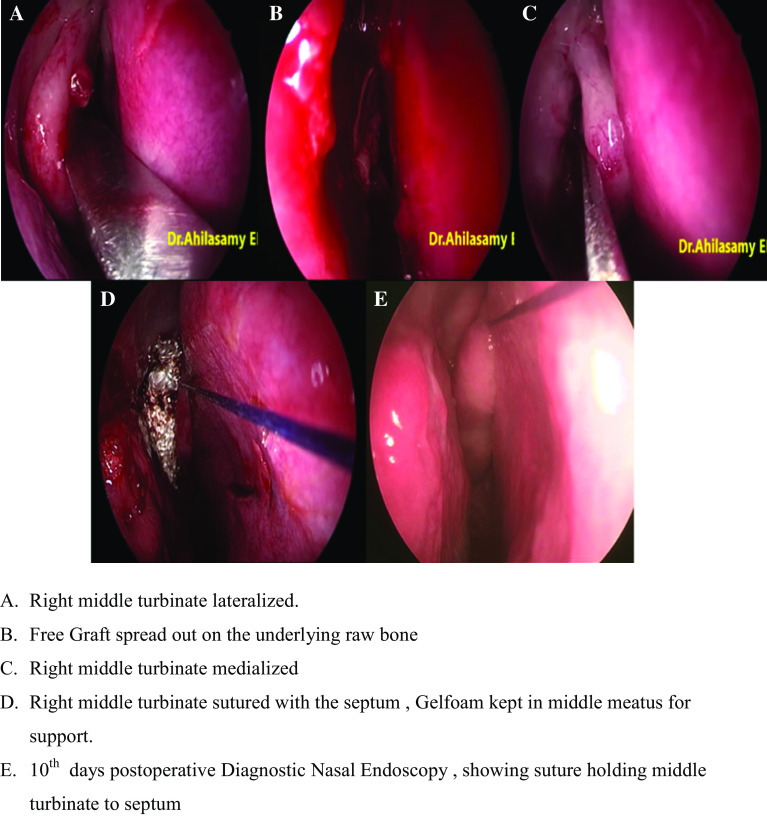

Surgical Procedure After proper decongestion of nasal cavity, middle turbinate and superior turbinate were lateralised to visualize the site of leak. In all cases lateralisation of middle turbinate was done. After localising the defect, the mucosa surrounding the defect was cauterised with bipolar cautery. If associated meningoencephalocele or meningocele were present, it was coagulated with bipolar cautery. Free mucosa from contralateral side of the septum was placed as overlay technique. Graft stabilised with surgicel after ensuring adequate contact between the graft and the defect site. If the leak didn’t stop after cauterization of pseudo menigocele or menigocele and if the defect is large then fat harvested from thigh is used as “bath plug” [5] to plug the defect, then free mucosal graft kept supported by surgicel. Finally the middle turbinate was medialized and sutured with 3 0′ Vicryl with nasal septum to support the graft and also to stabilize the middle turbinate as a quilting stich (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Left side cribriform plate CSF leak

Fig. 2.

Right side cribriform plate CSF leak

Closure No fibrin glue was used in our case series. No nasal packing was done. Patients discharged on 2nd or 3rd postoperative day.

Complications

In our series of 18 patients operated over 3 years (2016–2019), of managing Cribriform CSF leak repair with the help of a free septal mucosal graft without the need for any postoperative nasal pack material, we did not encounter any postoperative complications. There was no risk of recurrence with this proposed technique on long term follow up.

Results

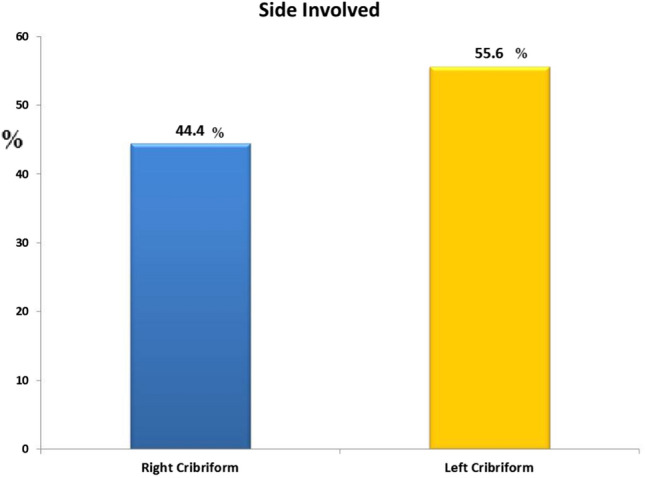

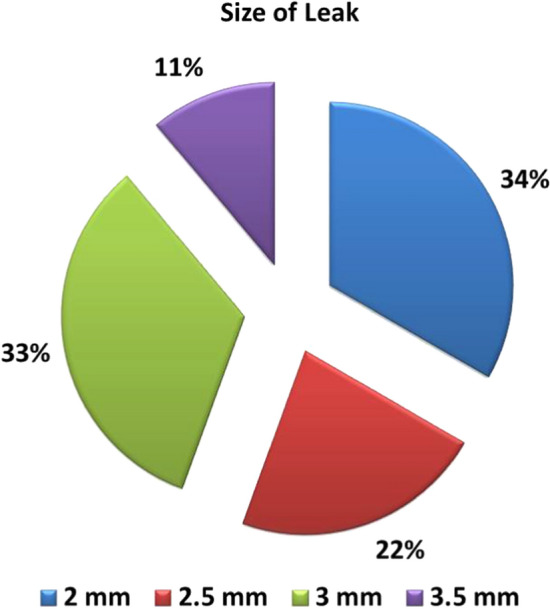

Among the 18 patients, 15 were females (83.3%) and 3 were males (16.7%) (Table 1), most prevalent age group was 31–40 years (55.6%) (Table 1). Left side cribriform plate was common (55.6%) (p 0.637) (Graph 1), spontaneous was most common etiology (83.3%) (p 0.005) (Graph 2), size of the leak is tabulated with p value of 0.485 (Graph 3) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of study on cribriform CSF leak: endoscopic surgical repair using free septal mucosal graft without postoperative nasal packs

| Number of cases | Percentage | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | |||

| < 20 years | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 21–30 years | 4 | 22.2 | |

| 31–40 years | 10 | 55.6 | |

| 41–50 years | 2 | 11.1 | |

| 51–60 years | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Female | 15 | 83.3 | |

| Side involved | |||

| Right cribriform | 8 | 44.4 | 0.637 (NS) |

| Left cribriform | 10 | 55.6 | |

| Etiology | |||

| Spontaneous | 15 | 83.3 | 0.005** |

| Traumatic | 3 | 16.7 | |

| Size of leak | |||

| 2 mm | 6 | 33.3 | 0.485 (NS) |

| 2.5 mm | 4 | 22.2 | |

| 3 mm | 6 | 33.3 | |

| 3.5 mm | 2 | 11.1 | |

NS not significant, **p < 0.01

Graph 1.

Side involved

Graph 2.

Etiology

Graph 3.

Size of the leak

Spontaneous CSF leaks are more common among middle aged obese patients. Cribriform plate is the most common site in spontaneous leak because of its thin and fragile nature.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS, version 17) for Microsoft windows. Descriptive statistics were presented as numbers and percentages A χ2 test was used for comparison between the attributes. A two sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The patients were followed up after surgery, postoperatively follow up were uneventful without the risk of any recurrence with the proposed technique.

Discussion

Spontaneous CSF rhinorrhoea can be high pressure or normal pressure leak. Obesity is an important risk factor which increases intra abdominal and intra thoracic pressure. This may effect blood circulation in cranial venous collectors and lead to development of benign intracranial hypertension [6, 7]. Spontaneous CSF leaks are mostly idiopathic. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with co-factors such as sneezing, coughing causes abnormal fluctuations in cerebrospinal fluid pressure [8]. The elevated pressure exerted on areas of the skull base result in remodelling and thinning of the bone. Ultimately, the bone is weakened resulting with a defect. If the defect is large, meninges may herniate as meningocele and brain parenchyma may herniate as meningoencephalocele. Anterior skull base is formed by cribriform medially and fovea ethmoidalis laterally. Cribriform has a medial lamella and a lateral lamella. Fovea extends from lateral lamella laterally to form the roof of ethmoidal sinuses. Lateral lamella is the part of cribriform plate lateral to middle turbinate attachment which lies lower than the level of fovea. Depth of olfactory fossa will depend on the height of lateral lamella [Keros classification]. Iatrogenic trauma are more common in lateral lamella Keros type 3. Medial lamella is the part of cribriform plate medial to middle turbinate attachment and has a thickness of 0.1–0.2 mm. The fragility of the plate and juxtaposition of the arachnoid’s investment to the bone, where the first cranial nerve perforates the skull, prolongation of subarachnoid space which follows the olfactory filament, slow erosion of skull base owing to fluctuations in Intracranial pressure (ICP) leading to point erosion which finally leaks through the weakest area makes this area of the skull base a vulnerable site for spontaneous CSF leak. CT coronal 1 mm cuts of paranasal sinuses, CT cisternography and MR cisternography help in identifying the site, side, size and the contents of leaking fistula [9–11].

Surgical management of CSF rhinorrhoea by Trans nasal endoscopic approach is less morbid and has a success rate of 90–100% [4].During repair, area surrounding the defect is made raw by stripping the mucosa or cauterization of the pseudo meningocele and surrounding mucosa to promote osteogenesis and fibrosis, better placement and take up of the graft and to reduce the incidence of mucocele formation. Being the thinnest part of skull base, medial cribriform plate if subjected to too much manipulation can cause enlargement of the defect size and micro fractures which may extend to the lateral lamella of cribriform, disruption of olfactory filament resulting in hyposmia. Hence in our technique we create raw area at defect site and adjacent area which include upper part of septum and upper part of middle turbinate by bipolar cauterization. Numerous grafting materials were used to close the defect such as abdominal fat, nasal septum mucosa, bone, fascia lata, temporalis fascia, conchal or septal cartilage and muscle grafts. Graft can be placed by different techniques like overlay, interlay, underlay, bath plug, sandwich multiple layer, blanket graft, gasket seal [12]. Here we have used a simple overlay technique. Advantage of using the overlay technique in this region is, olfactory epithelium is non-secretory, so even if the entire mucosa is not denuded, the chances of mucocele formation is negligible. Advantage of middle turbinate suturing is that it supports the graft repair and enhances synechiae formation which helps to retain the graft in position. Advantage of free mucosal grafts of septal graft is obtaining from opposite site, less operative time, less post operative morbidity We don’t pack the nasal cavity after surgery and patient can easily breathe through the nose postoperatively, early mobilization compared to other graft like fascia lata, temporalis fascia or polyvinyl nasal packs for 5–7 days as in various studies8. Nasal packing may sometimes lateralize the middle turbinate or may disturb layers used to close the defect with graft materials. Hence we avoid nasal packing postoperatively. Success rate is 100% with no recurrence on long term follow up. Reduced donor site morbidity. Less crusting as compared to fascia. If fat plug is used, then fat is harvested from the thigh through a small incision.

Conclusion

In our series the mean operating time was 40 min, with no post-operative morbidity, early mobilisation, with 100% success rate and no recurrence on long follow up.

With the help of free mucosal graft which is freely available inside the nasal cavity itself, cribriform leak repair become easy with less operating time and very high success rate comparable to other graft materials. No postoperative nasal pack hence no laterization of middle turbinate or disturbance (slippage) of graft by the pack and the patients can breathe easily through the nose postoperatively, early discharge from the hospital and hence good patient satisfaction.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Left Sided CSF Leak Repair (MP4 29388 kb)

Rigth Sided CSF Leak Repair (MP4 26900 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients who had undergone this procedure and had followed up timely, this encouraged us to share and submit this technique for publication in a scientific research journal.

Authors contribution

NA, chief operating surgeon, provided substantial contributions to the conception of the work; acquired, analysed, and interpreted the data for the work; and remained a continuous source of inspiration, encouragement, and motivation for submission for publication. VN, the corresponding author for this article, drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content and was involved in patient care and timely follow-up evaluator. DKR author was involved in final editing of the manuscript. RS contributed to preoperative and postoperative workup of the patients.

Funding

Nil.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nagalingeswaran Ahilasamy, Email: nahilasamy@yahoo.com.

Veerasigamani Narendrakumar, Email: drnarenent@gmail.com.

Dinesh Kumar Rajendran, Email: dinuraj1186@gmail.com.

Rajasekaran Sivaprakasam, Email: drsekar14@rediffmail.com.

References

- 1.Wax MK, Ramadan HH, Ortiz O, Wetmore SJ. Contemporary management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. OtolaryngolHead Neck Surg. 1997;116:442–449. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hao SP. Transnasal endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea: an interposition technique. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:501–503. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199604000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lanza DC, O’Brien DA, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae and encephaloceles. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1119–1125. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199609000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattox DE, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks and cephaloceles. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:857–862. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199008000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wormald PJ, Mcdonogh M. The bath-plug closure of anterior skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Rhinol. 2003;17(5):299–305. doi: 10.1177/194589240301700508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badia L, Loughran S, Lund V. Primary spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea and obesity. Am J Rhinol. 2001;15:117–119. doi: 10.2500/105065801781543736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark D, Bullock P, Hui T, Firth J. Benign intracranial hypertension: a cause of CSF rhinorrhea. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:847–849. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.7.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connell JEA. The cerebrospinal fluid pressure as an aetiological factor in the development of lesions affecting the central nervous system. Brain. 1953;76:279–298. doi: 10.1093/brain/76.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gacek RR, Gacek MR, Tart R. Adult spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid otorrhoea: diagnosis and management. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20:770–776. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(99)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson DBS, Toland BJ, O’Dwyer AJ. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:837–841. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(96)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gammal TE, Sobol W, Wadlington VR. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula: detection with MR cisternography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:627–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stankiewcz JA. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula and endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:250–256. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Left Sided CSF Leak Repair (MP4 29388 kb)

Rigth Sided CSF Leak Repair (MP4 26900 kb)