Abstract

Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) have a very poor prognosis due to the lack of efficient treatments. As observed in several other tumors, the effectiveness of treatments is mainly hampered by the presence of a highly tumorigenic sub-population of cancer cells called cancer stem cells (CSCs). Indeed, CSCs are resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and can regenerate the tumor bulk. Hence, innovative drugs that are efficient against both bulk tumor cells and CSCs would likely improve cancer treatment. In this study, we demonstrated that GNS561, a new autophagy inhibitor that induces lysosomal cell death, showed significant activity against not only the whole tumor population but also a sub-population displaying CSC features (high ALDH activity and tumorsphere formation ability) in HCC and in liver mCRC cell lines. These results were confirmed in vivo in HCC from a DEN-induced cirrhotic rat model in which GNS561 decreased tumor growth and reduced the frequency of CSCs (CD90+CD45-). Thus, GNS561 offers great promise for cancer therapy by exterminating both the tumor bulk and the CSC sub-population. Accordingly, a global phase 1b clinical trial in liver cancers was recently completed.

Keywords: GNS561, cancer stem cell, liver cancer, colorectal cancer, lysosome, therapy

Introduction

Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) have a very poor prognosis 1. They suffer from a lack of efficient therapy for HCC or treatment failures for CRC, both resulting in low survival rates. Since the late 1990s, a sub-population of poorly differentiated cancer cells, known as cancer stem cells (CSCs), have raised substantial interest, as they are believed to play a crucial role in cancer initiation, propagation, relapse and metastasis 2-5. According to the stem cell paradigm, CSCs are able to both self-renew and give rise to progenitors thus to generate the bulk of a tumor ad infinitum 6. This model has been validated for several tumor types, including HCC and CRC, whereas other ones, such as melanoma 7, do not exactly follow this pattern 8. It has also been shown that CSCs are resistant to various types of stress, including those generated by treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy 9,10. Recently, it was shown that apoptosis was induced in the majority of HCC tumor cells following treatment with sorafenib, a standard of care, whereas a subpopulation of CSCs remained and led to tumor metastases 11,12. In the same line, colorectal CSCs are not sensitive to radiotherapy or chemotherapy with oxaliplatin, irinotecan or 5-FU, leading to tumor metastasis and recurrence after chemotherapy 13. Thus, innovative drugs that simultaneously exterminate both bulk tumor cells and CSC subpopulation can improve cancer treatment and result in long-term tumor remission 4,8.

We previously reported that GNS561, a new lysosomotropic molecule with high hepatic tropism, was efficient against intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and HCC 14,15. Based on robust preclinical data, the potential use of GNS561 against primary and secondary liver cancers was evaluated in a global phase 1b clinical trial (NCT03316222), which was recently successful 16,17. Regarding its mode of action, GNS561 was shown to suppress cancer cell growth via the induction of apoptosis resulting from inhibition of palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1) activity, lysosomal unbound Zn2+ accumulation, impairment of cathepsin activity, blockage of autophagic flux, altered localization of mTOR, lysosomal membrane permeabilization and caspase activation 14.

The inhibition of autophagy induced by GNS561 suggests that this molecule could be effective in killing CSCs. Indeed, autophagy, as a catabolic and prosurvival pathway, appears to be critical for the survival of cancer cells and especially for the maintenance, plasticity, and chemoresistance of CSCs and their adaptation to tumor microenvironment changes (TME) 3,5,18,19. An increase in autophagy levels as a source of nutrient replenishment was reported in cancer cells and CSCs in response to increased metabolic demands triggered by environmental stress signals, such as hypoxia, starvation, metabolic and oxidative stresses and therapy 20,21. Therefore, autophagy inhibition might be a useful strategy for targeting and killing both cancer cells and CSCs 3,22-24.

In this study, we investigated the effect of GNS561 on CSCs. We first showed that in vitro, GNS561 induced a dramatic increase of CSC death in both HCC and liver mCRC cell lines. We then confirmed its efficacy on CSCs in vivo in an HCC-induced cirrhotic rat model.

Materials and Methods

Details of the materials and methods are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Cell lines

Hep3B cells were maintained in EMEM (ATCC) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Huh7 cells were cultured in DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), 1% GlutaMAX (Invitrogen) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco). Liver mCRC patient-derived cell lines (CPP19, 30, 36 and CPP45) 25 were maintained in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS. All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Diethylnitrosamine-induced cirrhotic immunocompetent rat model of HCC

Rats with HCC were treated with vehicle, GNS561 or sorafenib, by oral gavage for a period of six weeks. The animals were checked daily for clinical signs, effects of tumor growth and any other abnormal effects. All rats received humane care in accordance with the Guidelines on the Humane Treatment of Laboratory Animals (Directive 2010/63/EU), and experiments were approved by the animal Ethics Committee: GIN Ethics Committee No. 004.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8.4.3 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). For datasets with a normal distribution, multiple comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc analysis. For datasets without normal distribution, multiple comparisons were performed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Data are presented as the mean values ± standard error mean (SEM) of three independent experiments unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance is indicated by one (P-value < 0.05) or two (P-value < 0.01) asterisks on the figures.

Results

GNS561 is efficient against the whole tumor

We first investigated the activity of GNS561 in the whole population of two HCC cell lines and four liver mCRC cell lines. GNS561 decreased viability in a dose-dependent manner, with very similar maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for all the tested cell lines and < 3 µM (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitro activity (IC50) of GNS561 on two HCC (Hep3B and Huh7) and four liver mCRC cell lines (CPP19, CPP30, CPP36 and CPP45) after 72 h of treatment with GNS561.

| Name | IC50 (µM) | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCC cell lines | Hep3B | 2.33 | 2.358 to 2.535 |

| Huh7 | 1.48 | 1.238 to 1.699 | |

| Liver mCRC cell lines | CPP19 | 1.88 | 1.424 to 2.487 |

| CPP30 | 1.22 | 0.9210 to 1.624 | |

| CPP36 | 1.45 | 0.6990 to 3.025 | |

| CPP45 | 1.12 | 0.9555 to 1.318 |

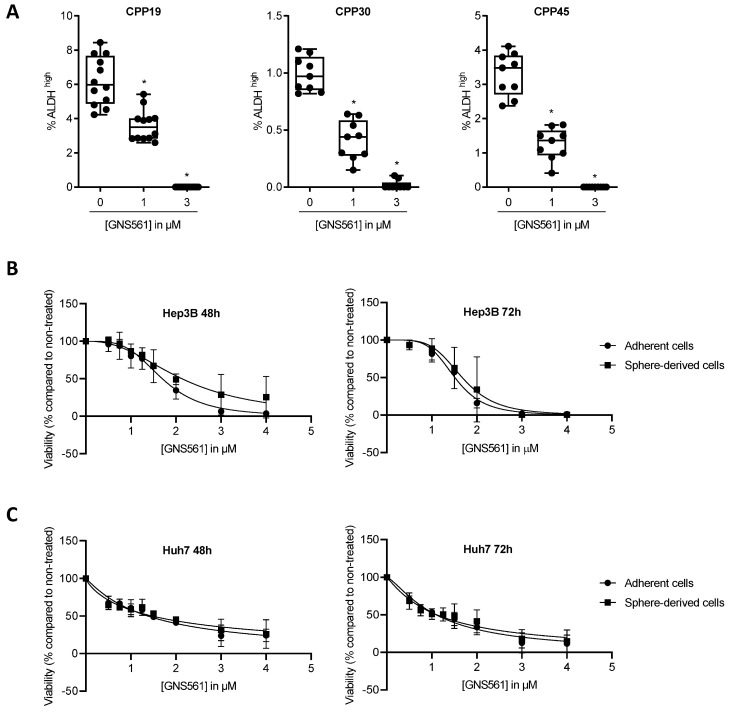

GNS561 is also active against a subpopulation displaying CSC features

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is known to be a marker of CSCs in numerous solid cancers, including CRC 26,27. To evaluate the sensitivity to GNS561 of the CSC/cancer progenitor cell-enriched subpopulations of liver mCRC cell lines, the percentage of ALDHbright cells was quantified by flow cytometry after 72 h of incubation with GNS561. As shown in Fig. 1A, GNS561 significantly decreased the percentage of ALDHbright cells in a dose-dependent manner in all three mCRC cell lines.

Figure 1.

GNS561 is efficient against subpopulation displaying CSC features. (A) Box and whisker representation (min to max) of the percentage of ALDHbright cells after 72 h of treatment with GNS561 in three liver mCRC cell lines with the indicated concentrations. For comparison with the control, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc analysis was performed. *, P < 0.05. Antitumor activity of GNS561 on whole tumor (circle) or CSC-enriched populations (square) in Hep3B (B) and Huh7 (C) HCC cell lines after 48 or 72 h of treatment with GNS561. The curves represent the mean of two independent experiments in triplicate.

Unlike CRC cells, ALDH-overexpressing HCC cells seem to exhibit a differentiated rather than a CSC phenotype 28. Moreover, there is a lack of consensus biomarkers for CSCs in HCC 24,29. Consequently, the CSC subpopulation is commonly identified in HCC based on functional criteria such as their capacity to efflux Hoechst 33342 dye (side population) 30 or to form tumorspheres 31,32, as only these cells have the ability to proliferate in non-adherent conditions 33,34. Tumorsphere formation assay was used to isolate the CSC subpopulation of HCC cell lines. The significant overexpression of the stemness-associated factors SOX2 and NANOG in Hep3B tumorspheres compared to the whole cell population confirmed their immature phenotype (Fig. S1). To avoid chemoresistance because cells within the interior of tumorspheres are protected from drug penetration by neighboring cells on the periphery of the sphere, we compared the impact of GNS561 between the whole and CSC-enriched populations of Hep3B and HuH7 cell lines in monolayer cultures. GNS561 had the same effect on the viability of the two populations from Hep3B (Fig. 1B) or Huh7 (Fig. 1C) cells treated in monolayer cultures for 48 or 72 h. Since cells with an immature phenotype have high plasticity when cultured in vitro, we hypothesized that they could have derived after 48 or 72 h of monolayer culture and spontaneously restored the initial heterogeneous population 6. Thus, we repeated the experiment in Hep3B cells and assessed the antitumor activity of GNS561 at shorter times (6, 8 and 24 h) and at higher doses (0.5 to 32 µM). Similarly, GNS561 was as efficient against the bulk population as the CSC-enriched population (Fig. S2).

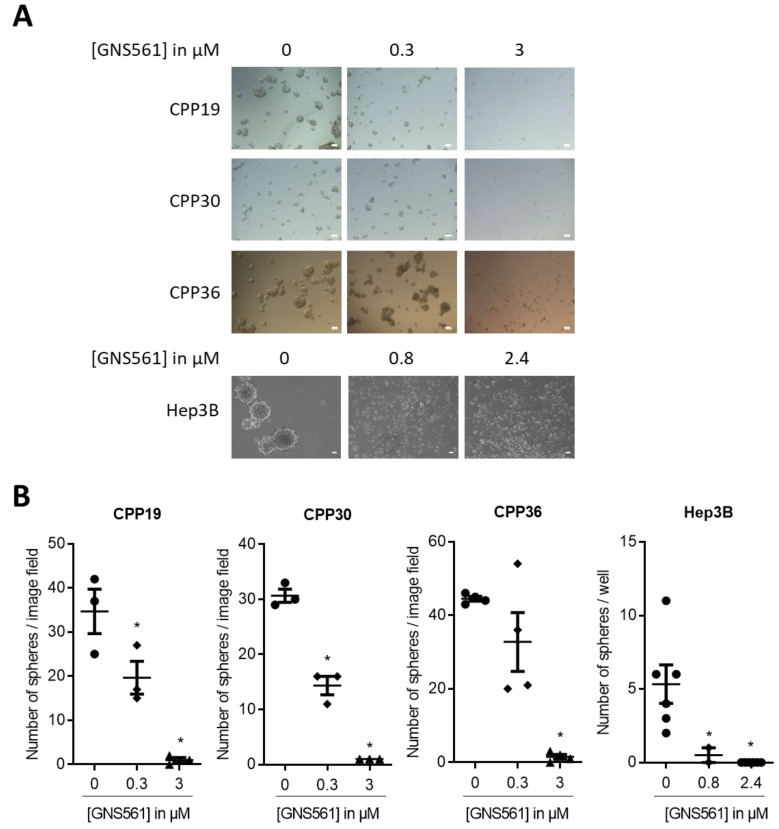

GNS561 blocks tumorsphere formation

Then, the ability of GNS561 to impair tumorsphere formation was investigated in both liver mCRC and HCC cell lines. GNS561 (0.3 or 3 µM) was added after seeding a low number of liver mCRC cells in CSC medium. Ten days later, tumorspheres > 50 µm were counted. As shown in Fig. 2A and 2B, GNS561 induced significant dose-dependent decreases in tumorspheres in all three cell lines, with complete suppression of tumorspheres at the highest dose (3 µM). Similar results were obtained with the Hep3B HCC cell line at 96 h (Fig. 2A and B) and 11 days (data not shown) after GNS561 treatment. As illustrated in Fig. 2, GNS561 completely inhibited tumorsphere formation, even at low concentration (0.8 µM corresponding to 1/3 IC50 in the adherent whole population). These results showed that GNS561 has an antitumor effect not only on the bulk, but also on the CSC-enriched subpopulation. In order to further enrich the CSC population, secondary spheres were generated from primary Hep3B spheres and treated with the same doses of GNS561. A slight difference in sensitivity was observed between primary and secondary spheres, with a complete inhibition of sphere formation reached at 0.8 and 1.6 µM, respectively (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3). These results confirm the significant activity of GNS561 on CSCs. In contrast, sorafenib had only a mild effect on the CSC-enriched subpopulation since it failed to completely abolish tumorsphere formation whether from adherent cells or primary spheres (Fig. S3 and S4).

Figure 2.

GNS561 alters the self-renewal of liver mCRC and HCC cell lines. (A) Tumorsphere forming efficiency of three liver mCRC (CPP19, CPP30 and CPP36) and one HCC (Hep3B) cell lines treated with the indicated GNS561 concentrations. Scale bars represent 50 µm. (B) Number of spheres > 50 µm. For comparison with the control, statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test. *, P < 0.05.

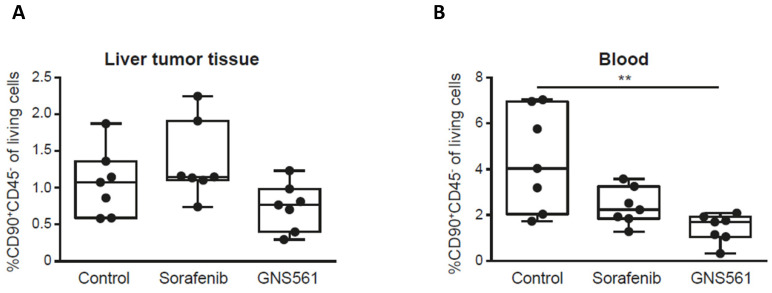

GNS561 decreases tumor growth and CSCs in a diethylnitrosamine‐induced cirrhotic rat model of HCC

As demonstrating the antitumor activity of a drug on CSCs by tumorsphere formation in vitro could reflect its in vivo anti-tumor efficiency 35, we investigated its efficacy on CSCs in vivo.

GNS561 has been previously shown to have potent antitumor activity in two HCC in vivo models including a diethylnitrosamine-induced cirrhotic rat model of HCC 14. Here, we used the same model to study the impact of GNS561 on the frequency of CSCs in vivo. Rats with already developed HCC were either treated with vehicle, sorafenib (a standard of care of HCC) at 10 mg/kg or GNS561 at 15 mg/kg. The CD90+CD45- phenotype was used to identify and quantify CSCs, since it has been reported to be associated with CSCs in liver tumor tissues and with circulating CSCs in blood samples 36-38. In our rat model, no significant decrease was observed in the frequency of CSCs from the liver tumor tissue between the GNS561-treated group and the control group (Fig. 3A). However, the decrease in circulating CSCs became significant in the GNS561-treated group compared with the control group in the circulating CSCs (p = 0.0067, Fig. 3B). Notably, sorafenib, which is widely used to treat advanced HCC in humans, had no significant effect on the percentage of CSCs.

Figure 3.

GNS561 decreases CSC frequency in vivo. Box and whisker representation (min to max) of the percentage of CSCs in liver tumor (A) and blood (B) samples in a diethylnitrosamine-induced cirrhotic rat model of HCC. Rats received vehicle (control), sorafenib at 10 mg/kg or GNS561 at 15 mg/kg. For comparison with the control non-treated group, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. **, P < 0.01.

Discussion

HCC and mCRC are refractory to most conventional chemotherapies. One of the reasons for the high mortality rate is the existence of a small population of CSCs with high tumorigenicity and resistance to drugs. Accordingly, many cancer therapies, while killing the bulk of tumor cells, may ultimately fail because they do not eliminate CSCs that reform heterogeneous tumors.

GNS561 is a small molecule that showed potent antitumor activity in vitro in a panel of human cancer cells, including HCC patient-derived cells, and in vivo in two HCC different models 14. The in vitro studies performed in this study clearly showed that GNS561 displays potent dose response activity when assayed against a panel of human colon tumor cells isolated from liver metastases. In addition, GNS561 was efficient against subpopulation displaying ALDHbright activity and produced a dramatic decrease in the ability of these cells to form tumorspheres. Similarly, in two HCC cell lines, GNS561 was equally effective in both populations (bulk and CSCs) and dramatically decreased the cell capacity to form spheres, even at low doses, unlike sorafenib, a standard of care. This latter observation was in agreement with the literature. Indeed, CSC resistance to sorafenib has been widely reported and has been cited as responsible for treatment failure and relapse 39,40.

Taken together, our results strongly suggest that GNS561 was efficient against both the whole tumor cell population and cell subpopulations displaying CSC features (ALDHbright cells and tumorsphere initiating cells). These original results were confirmed in vivo, in a HCC-induced cirrhotic rat model, in which GNS561 showed antitumor effects and reduced the frequency of CSCs in liver tumor tissue and circulating CSCs. To go further, it would be informative to xenograft tumorsphere-derived CSCs or serial transplant tumors to determine GNS561 activity on the tumor growth.

The effectiveness of GNS561 to kill both tumor bulk cells and CSCs can be explained by its capacity to inhibit autophagy and lysosomal functions and to disrupt lysosomes 14. In fact, once established, tumors require an uninterrupted nutritional supply for maintaining their proliferative needs in stressful conditions such as hypoxia, nutrient and growth factor starvation, and oxidative and metabolic stress 18. In this context, autophagy has a protumoral activity by providing recycled bioenergetic substrates and consequently overcoming nutritional deficiency and favoring the survival of cancer cells 41. Concerning the CSC population, autophagy was shown to be a major factor for the preservation of cell homeostasis and the maintenance of stemness properties 5. Consistently, it was reported that metastatic cells and CSCs are vulnerable to lysosomal inhibition and disruption 42-45. For example, inhibition of autophagic flux and lysosomal functions by salinomycin interferes with the maintenance and expansion of breast cancer stem-like/progenitor cells 46. Moreover, a salinomycin derivative has been showed to be able to sequester iron in lysosomes ultimately resulting in cell death of CSCs 45,47. Mefloquine showed activity on acute myeloid leukemia cells and progenitors by disrupting lysosomes (lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cytosolic release of cathepsins) 48.

Further research will be necessary to better understand the underlying mechanisms implicated in GNS561 activity against CSCs. It would be interesting to evaluate whether GNS561 treatment results from GNS561-induced inhibition of PPT1 and the mTOR pathway and lysosomal zinc sequestration in CSCs, as demonstrated in whole tumors 14. In fact, knockout of PPT1 in tumor cells inhibited tumor growth, tumorsphere formation and tumorigenesis in vivo 49, suggesting that PPT1 may be implicated in CSC maintenance. In turn, the mTOR pathway has been shown to be one of the most important pathways involved in the development and progression of cancer and in the maintenance and hallmarks of CSCs 50, implying that inhibition of the mTOR pathway could be a good therapeutic strategy to eradicate CSCs. Moreover, as autophagy is an adaptive mechanism modulating the TME surrounding CSCs to support their stemness and cancer propagation 20, studying the effect of GNS561 on the TME would be of broad interest. Finally, it was recently reported that interfering with iron homeostasis using small molecules alters epigenetic plasticity of cells 51. To evaluate if zinc could also be a regulator of epigenetic plasticity and if GNS561, by sequestrating lysosomal zinc, impairs this process would also be of particular interest.

In conclusion, GNS561 showed activity against not only the whole tumor population but also against subpopulations displaying CSC features in vitro and in vivo. Thus, a strategy that simultaneously exterminates the CSC subpopulation and tumor bulk by using autophagy inhibitors and lysosomal disruptors, such as GN561, is promising as a new direction to achieve cure and to prevent relapse of liver primary cancer and metastasis. GNS561 could also be used in combination with other drugs, in order to enhance the overall anticancer effect, as already described for hydroxychloroquine in several tumor types (reviewed in 3). In particular, as classical chemo- or radiotherapy mainly fails to eliminate the CSCSs present in many tumor types, GNS561 could be useful to target these CSCs and then to reduce the risk of relapse in patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Dr. Michel Prudhomme and Dr. Jean-François Bourgaux from CHU Carémeau, Nîmes, France, for the use of liver mCRC cells and Dr Mirjam Zeisel for English proofreading.

Abbreviations

- ALDH

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- IC50

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- mCRC

metastatic colorectal cancer

- PPT1

palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1

- SEM

standard error mean

- TME

tumor microenvironment

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet D. Cancer stem cells: lessons from leukaemia. Cell Prolif. 2005;38:357–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nazio F, Bordi M, Cianfanelli V, Locatelli F, Cecconi F. Autophagy and cancer stem cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:690–702. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun JH, Luo Q, Liu LL, Song GB. Liver cancer stem cell markers: Progression and therapeutic implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3547–57. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i13.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitale I, Manic G, Dandrea V, De Maria R. Role of autophagy in the maintenance and function of cancer stem cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2015;59:95–108. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.150082iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH Jones DL. et al. Cancer stem cells-perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. 2008;456:593–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Tackling the cancer stem cells - what challenges do they pose? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:497–512. doi: 10.1038/nrd4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Y, Xia L, Wang H, Oyang L, Su M, Liu Q. et al. Cancer stem cells in progression of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9:33403–15. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulte L-A, López-Gil JC, Sainz B, Hermann PC. The Cancer Stem Cell in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers. 2020;12:684. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Jin R, Zhao J, Liu J, Ying H, Yan H. et al. Potential molecular, cellular and microenvironmental mechanism of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng CC, Chao WT, Liao CC, Shih JH, Lai YS, Hsu YH. et al. The Roles Of Angiogenesis And Cancer Stem Cells In Sorafenib Drug Resistance In Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:8217–27. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S217468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das PK, Islam F, Lam AK. The Roles of Cancer Stem Cells and Therapy Resistance in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cells. 2020. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Brun S, Raymond E, Bassissi F, Jikova ZM, Mezouar S, Rachid M, GNS561, a clinical-stage PPT1 inhibitor, has powerful antitumor activity against hepatocellular carcinoma via modulation of lysosomal functions. bioRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Brun S, Bassissi F, Serdjebi C, Novello M, Tracz J, Autelitano F. et al. GNS561, a new lysosomotropic small molecule, for the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2019;37:1135–45. doi: 10.1007/s10637-019-00741-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ClinicalTrials. gov. Study of GNS561 in Patients With Liver Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- 17.Harding JJ, Awada A, Decaens T, Roth G, Merle P, Kotecki N. et al. First-in-human phase I, pharmacokinetic (PK), and pharmacodynamic (PD) study of oral GNS561, a palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1) inhibitor, in patients with primary and secondary liver malignancies. JCO. 2021;39:e16175–e16175. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojha R, Bhattacharyya S, Singh SK. Autophagy in Cancer Stem Cells: A Potential Link Between Chemoresistance, Recurrence, and Metastasis. Biores Open Access. 2015;4:97–108. doi: 10.1089/biores.2014.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharif T, Martell E, Dai C, Kennedy BE, Murphy P, Clements DR. et al. Autophagic homeostasis is required for the pluripotency of cancer stem cells. Autophagy. 2017;13:264–84. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1260808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandhair HK, Arambasic M, Novak U, Radpour R. Molecular modulation of autophagy: New venture to target resistant cancer stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2020;12:303–22. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v12.i5.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Hout M, Cosialls E, Mehrpour M, Hamai A. Crosstalk between autophagy and metabolic regulation of cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:27. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li N, Zhu Y. Targeting liver cancer stem cells for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:175628481882156. doi: 10.1177/1756284818821560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith AG, Macleod KF. Autophagy, cancer stem cells and drug resistance. J Pathol. 2019;247:708–18. doi: 10.1002/path.5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Zhang J, Zhang X, Zhou H, Liu G, Li Q. Cancer Stem Cells: A Potential Breakthrough in HCC-Targeted Therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:198. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grillet F, Bayet E, Villeronce O, Zappia L, Lagerqvist EL, Lunke S. et al. Circulating tumour cells from patients with colorectal cancer have cancer stem cell hallmarks in ex vivo culture. Gut. 2017;66:1802–10. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Appelman H. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3382–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassalli G. Aldehyde Dehydrogenases: Not Just Markers, but Functional Regulators of Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:3904645. doi: 10.1155/2019/3904645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka K, Tomita H, Hisamatsu K, Nakashima T, Hatano Y, Sasaki Y. et al. ALDH1A1-overexpressing cells are differentiated cells but not cancer stem or progenitor cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24722–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores-Tellez TN, Villa-Trevino S, Pina-Vazquez C. Road to stemness in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6750–76. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiba T, Kita K, Zheng Y-W, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Iwama A. et al. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatol Baltim Md. 2006;44:240–51. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao L, Zhou Y, Zhai B, Liao J, Xu W, Zhang R. et al. Sphere-forming cell subpopulations with cancer stem cell properties in human hepatoma cell lines. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida Y, Tanaka S, Aihara A, Adikrisna R, Yoshitake K, Matsumura S. et al. Analogy between sphere forming ability and stemness of human hepatoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:1147–51. doi: 10.3892/or_00000966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson S, Chen H, Lo PK. In vitro Tumorsphere Formation Assays. Bio Protoc. 2013. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Ma XL, Sun YF, Wang BL, Shen MN, Zhou Y, Chen JW. et al. Sphere-forming culture enriches liver cancer stem cells and reveals Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 as a potential therapeutic target. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:760. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5963-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C-H, Yu C-C, Wang B-Y, Chang W-W. Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1215–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Motawi TK, El-Boghdady NA, El-Sayed AM, Helmy HS. Comparative study of the effects of PEGylated interferon-alpha2a versus 5-fluorouracil on cancer stem cells in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:1617–25. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3920-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang ZF, Ngai P, Ho DW, Yu WC, Ng MN, Lau CK. et al. Identification of local and circulating cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Hepatology. 2008;47:919–28. doi: 10.1002/hep.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN, Lau CK, Yu WC, Ngai P. et al. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao J, Zhao M, Liu J, Zhang X, Pei Y, Wang J. et al. RACK1 Promotes Self-Renewal and Chemoresistance of Cancer Stem Cells in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Stabilizing Nanog. Theranostics. 2019;9:811–28. doi: 10.7150/thno.29271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Y, Jiang W, Zhao W, Lu Z, Gu Y, Dong Y. miR-124 regulates liver cancer stem cells expansion and sorafenib resistance. Exp Cell Res. 2020;394:112162. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim J, Murthy A. Targeting Autophagy to Treat Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:590344. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.590344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cash TP, Alcala S, Rico-Ferreira MDR, Hernandez-Encinas E, Garcia J, Albarran MI, Induction of Lysosome Membrane Permeabilization as a Therapeutic Strategy to Target Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers Basel. 2020. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Morgan MJ, Fitzwalter BE, Owens CR, Powers RK, Sottnik JL, Gamez G. et al. Metastatic cells are preferentially vulnerable to lysosomal inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U A. 2018;115:E8479–88. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706526115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salerno M, Avnet S, Bonuccelli G, Hosogi S, Granchi D, Baldini N. Impairment of lysosomal activity as a therapeutic modality targeting cancer stem cells of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Versini A, Colombeau L, Hienzsch A, Gaillet C, Retailleau P, Debieu S. et al. Salinomycin Derivatives Kill Breast Cancer Stem Cells by Lysosomal Iron Targeting. Chemistry. 2020;26:7416–24. doi: 10.1002/chem.202000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mai TT, Hamaï A, Hienzsch A, Cañeque T, Müller S, Wicinski J. et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem. 2017;9:1025–33. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yue W, Hamai A, Tonelli G, Bauvy C, Nicolas V, Tharinger H. et al. Inhibition of the autophagic flux by salinomycin in breast cancer stem-like/progenitor cells interferes with their maintenance. Autophagy. 2013;9:714–29. doi: 10.4161/auto.23997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sukhai MA, Prabha S, Hurren R, Rutledge AC, Lee AY, Sriskanthadevan S. et al. Lysosomal disruption preferentially targets acute myeloid leukemia cells and progenitors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:315–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI64180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rebecca VW, Nicastri MC, Fennelly C, Chude CI, Barber-Rotenberg JS, Ronghe A. et al. PPT1 Promotes Tumor Growth and Is the Molecular Target of Chloroquine Derivatives in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:220–9. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia P, Xu XY. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in cancer stem cells: from basic research to clinical application. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:1602–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Müller S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T, Lafon A, Versini A, Lombard B. et al. CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis. Nat Chem. 2020;12:929–38. doi: 10.1038/s41557-020-0513-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.